Abstract

Empowering women is a policy goal that has received a lot of interest from policy-makers in the developing world in recent years, yet little is known about effective ways to promote it sustainably. Most existing interventions fail to address the multidimensional nature of empowerment. Using a double matching design to construct the sampling frame and to estimate causal effects, I evaluate the long-term impact of a multifaceted policy intervention designed to improve women’s empowerment in the Atlantic region in Colombia. This intervention provided information about women’s rights, soft skills and vocational training, seed capital, and mentoring simultaneously. I find that this intervention has mixed results: there are improvements in incomes and other economic dimensions along with large political and social capital effects, but limited or null impacts on women’s rights knowledge and control over one’s body. Using a list experiment, I even find an increase in the likelihood of intra-household violence. The results highlight the importance of addressing the multidimensional nature of women’s empowerment in policy innovations designed to foster it and incorporating men in these efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Empowerment was introduced into economics by Sen (1999) and is related to fundamental concepts such as power and agency. Common elements in existing frameworks (Fox & Romero, 2017) include aspirations and self-efficacy as well as the behavioral dimension of action, the fact that individuals operate in environments with formal and informal behavioral constraints, and the idea that empowerment is a process and an outcome. Although there are some important differences among them, these approaches are interpreted as complementary in the rest of the paper.

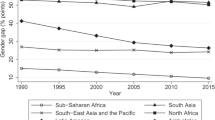

The empirical evidence is clear in this regard. Female participation in the labor market is still low, with labor earnings typically below those of men for similar occupations (Klasen, 2019) and Jayachandran (2020). Many women have children at a younger age due to limited access to contraceptive methods, and lack of information (Upadhyay et al., 2014). Educational opportunities are still unequal (Aslam, 2013) and Heath and Jayachandran (2018), and violence towards women is more prevalent and acceptable due to social norms (Vyas & Watts, 2009). Gender gaps in political participation and voice are still prevalent, which has led to a large underrepresentation in political office and leadership positions (Milazzo & Goldstein, 2019). Although some progress in many economic, political, and social dimensions has been documented (World Bank, 2012) and Buvinic and Furst-Nichols (2016), there are many areas in which women still face considerable disadvantages with respect to men.

A review paper of (mostly) unidimensional empowerment interventions by Baird and Ozler (2016) concludes that “...studies that exist generally do not point to meaningful and sustained effects on key indicators of economic empowerment.” (p. 16)

Unfortunately, data for the program’s participants not included in SISBEN is not available. The information collected by the program was minimal; therefore, this group of participants was discarded when constructing the sampling frame. Consequently, I cannot provide details about this set of participants.

They study the Empowerment and Livelihood for Adolescent (ELA) program in Uganda, which provides vocational and soft skills training using social clubs. This program was implemented by the NGO BRAC and was expanded to several countries in Africa and Asia, including Liberia, Nepal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, and Tanzania. This program successfully increased girls’ participation in economic activities, reduced early pregnancy and marriage, and raised aspirations regarding marriage, childbearing, and fertility.

They study a similar ELA program in Tanzania that included a microcredit component and explored similar outcomes as Bandiera et al. (2020) without finding improvements in any of these outcomes but some evidence in terms of increases in savings.

They study the AGEP program’s effects in Zambia on empowerment outcomes for young girls. This program provided vocational and socio-emotional skill training using clubs, vouchers for health services, and a savings account. The intervention did not lead to relevant changes in economic assets, educational, or fertility outcomes.

They analyze the effect of an empowerment intervention in Egypt based on vocational, business, and life skills training (including some basic support for legal registration and opening bank accounts) on labor market and entrepreneurship outcomes. Using a matching-differences in difference design, the authors find medium-size effects of this intervention on labor outcomes.

They study the effects of an empowerment program in India that provided seed funds, access to financial services, and training in business and life skills on a broad set of assets and expenditures, human development, and women’s empowerment outcomes. The authors find positive impacts on asset accumulation, increases in household expenditures, and larger investments in education, along with positive changes in women’s autonomy, mobility, and participation in social activities.

The evidence for vocational training suggests that these interventions have some effects on labor market outcomes but they are typically modest (McKenzie, 2017) These results do not seem to be different for women. Regarding business training, the evidence suggests that they are effective in improving business practices but their effects on profits and business survival are small (McKenzie, 2021) and (Woodruff & McKenzie, 2012).

A recent scholarship has shown that soft skills can boost profits, employment, and crop adoption for women (and also men). See, for instance, the evidence provided by Edmonds et al. (2021) for India, Ashraf et al. (2020) for Zambia, Campos et al. (2017) for Togo, Montalvao et al. (2017) for Malawi, and Croke et al. (2017) for Nigeria.

Two recent papers have shown the positive impacts of mentoring on microenterprise-level outcomes. Brooks et al. (2018) study the effects of a mentorship program for inexperienced female microentrepreneurs in Kenya finding a 20% increase in profits. On the other hand, Lafortune et al. (2018) evaluate a similar intervention in Chile where personalized consulting sessions are compared to role models. These role models are former participants of a training program. They find that both interventions raised household income by 15%, being the role model one more cost-effective.

The evidence in this regard is mixed. de Mel et al. (2008) documents large effects of small infusions of capital on profits for male-headed small enterprises. The short-term effects are close to 6% and five years later are close to 12% (de Mel et al., 2012). The effect for female-headed small firms is indistinguishable from zero. Fafchamps et al. (2016) study a similar intervention in Ghana, finding differential effects by gender. In the case of female-owned microenterprises, only in-kind grants seem to have a positive effect, especially for businesses of larger size. However, if one focuses on smaller female-headed firms, the returns to capital disbursement are close to zero.

In the Atlantico department, women’s participation rate is 52% versus 78% for men. The unemployment rate for women is 11% versus 5% for men, and the wage gap is 19%. See Fonseca (2019) for details.

This idea is reinforced by the fact that the program opened additional slots for beneficiaries affected by seasonal rains in 2010, with a clear goal of targeting women economically affected by natural disasters. Hence, socioeconomic conditions and economic vulnerability played an important role in the selection process.

Own calculation based on program information. Unfortunately, detailed information about the program’s cost structure is not available to perform a cost-benefit analysis. See SMEG (2020) for details.

These and the following calculations in this section are based on the evaluation survey carried out by CNC in March, 2017.

It is also important to mention that the development of the business plan created expectations regarding the amount that it was unfeasible for the program to cover. Almost all treated women reported a negative perception of this program’s component.

Unfortunately, the heterogeneity among participants was a significant barrier in this regard. It was hard for the program to create these associations, except in cases where participants were friends or neighbors before the start of the program. Many of these associations did not work in the long term. Because the delivery of the seed capital was planned to be at the level of these associations, this process encountered important challenges. The evaluation team reported encountering many women still waiting for the seed capital during the data collection process. In many cases, when seed capital was distributed, it was common that members of a given association decided to split this capital among its members.

A genetic algorithm solves complex optimization problems using heuristics inspired by the natural selection process. A population of potential solutions is evaluated iteratively. In each iteration or generation, the fitness of every individual in the population is evaluated. The more fit individuals are selected from the current population, and each individual’s genome is modified to form a new generation. The new generation of potential solutions is used in the next iteration of the genetic algorithm. See Sekhon and Mebane (1998) for details.

According to the simulations implemented by Colson et al. (2016), genetic matching has the best covariate balance among 7 alternative methods even when there is poor support in terms of the propensity score. This advantage is consistent across alternative balance metrics.

Alternative formulations of these assumptions also include some regularity conditions, whether the set of covariates X has continuous distributions and restrictions about the sampling process. See Abadie and Imbens (2011) for details.

These departments were included in the sampling frame because of potential concerns of within-municipality spillovers. As mentioned later, the sample size is not large enough to exploit this feature of the sampling design in the analysis.

One implication of this feature of my research design is the existence of repeated treated observations in the sampling frame. This characteristic is not present in the final sample. As it will be shown later, this does not affect the quality of the final sample.

As it is well-known, power calculations for measuring spillover effects are typically very demanding. Therefore, the sampling design was designed to provide only suggestive evidence about externalities.

It is unclear whether the size of within-municipality spillovers is relevant in this setting, but some international evidence is available. For the case of young girls in Uganda, Bandiera et al. (2020) present suggestive evidence of spillovers for aspirations and control over the body indices, but weaker effects for economic empowerment. Some evidence for within-household spillovers will be discussed later.

Standardized differences compare the difference in means in units of the pooled standard deviation, and it has the advantage of not being influenced by sample size. See Imbens (2015) for details.

Trimming of the sample did not affect the balance in terms of pre-treatment characteristics between treatment and control groups (results not shown).

For a discussion of descriptive versus analytical designs, see Roy et al. (2016).

The full definition of these variables is the same as the ones in the sampling frame and is presented in Table S2 in the Online Appendix.

A detailed discussion about the steps involved in this algorithm can be found in Appendix A of Imbens (2015).

One important issue is that the propensity score is a generated regressor and, as such, standard errors should account for this fact. The recommended solution for this problem is bootstrapping standard errors, but Abadie and Imbens (2008) have highlighted the problems with this alternative for matching. Abadie and Imbens (2016) study the case where matching is done exclusively on the propensity score without additional covariates—as in this paper—and show that, for the case of ATET, ignoring the estimation error has ambiguous effects on the size of confidence intervals. Because there is no clear suggestion in the technical literature about how this issue should be addressed, I proceed like the rest of the empirical literature, by ignoring this issue.

Using more than one match can improve precision but also can increase bias because it increases the average covariate discrepancy between matches. Intuitively, adding a match will decrease the match quality. These authors suggest that “...going beyond two or three matches can only lead to small improvements in the sampling precision…” (Imbens & Rubin, 2015): 427. Therefore, I use two matches as suggested by these authors.

Recall that the population size in genetic algorithms represents the set of potential solutions for the optimization problem of interest.

Using this threshold is stricter than the standard proposed by Imbens (2015). I follow this approach to be more demanding with this element of my research design.

This procedure ranks the number m of hypotheses \(H_{(i)}\) according to their uncorrected p-values \(P_{(i)}\) and sets a proportion q of rejected null hypotheses that are erroneously rejected. Then, letting k be the largest i for which \(P_{(i)} \le \frac{i}{m} q\); the procedure rejects all \(H_{(i)},i=1,2,...,k\) that violate this weak inequality. See Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) for details.

The equivalence of the derivation based on assignment probabilities and the original derivation based on unobserved covariates is proved in Proposition 12 of Rosenbaum (2002).

See Rosenbaum (2002), Chapter 4, for details. There are three main assumptions behind this approach. First, a logit form linking treatment assignment to observed and unobserved covariates is assumed. Second, the unobserved covariates are constrained to be in the (0,1) range. Finally, there are no interaction terms between observed and unobserved covariates. The second assumption seems to be restrictive, but it has many interpretations. The most straightforward interpretation assumes the unobserved factors as dummy variables. However, an alternative interpretation is to see this assumption as a restriction regarding the scale of the unobserved covariates to provide meaning to the numerical value of the \(\gamma \) parameter. As suggested by Rosenbaum (2002), this restriction can be relaxed.

All monetary measures were converted from Colombian Pesos to US dollars using the exchange rate of February 2017 (USD 1= COP 2,879.57)

This multidimensional poverty indicator was developed using the methodology proposed by Schreiner (2014), and it has been used in around 60 countries. It considers ten indicators of family size, education, labor supply, access to electricity, source of energy for food preparation, and household assets.

The minimum wage in Colombia in 2017 was COP 737,717, about USD 256.

These results are consistent with the effects of multifaceted programs for the poor. For instance, effects for income (0.20 standard deviations (SDs) for TTM) are smaller than the ones reported by Banerjee et al. (2015) (0.38 SDs). However, these effects do not distinguish women from men. A more similar case is Bandiera et al. (2017). They report a 21% increase in earnings with respect to the control group, smaller than the 31% increase in incomes estimated for TTM. Regarding other women’s empowerment programs, Bandiera et al. (2020) find no effects on expenditures after four years, and Buehren et al. (2017) report null effects on labor incomes. Of course, these comparisons are suggestive since differences in categories across studies may be related to differences in data collection methods and methodological differences for capturing incomes and expenditures.

This reduction was larger than the observed in some of the multifaceted programs for the poor. For instance, in Bandiera et al. (2017), this reduction was 14% after four years for poor women in Bangladesh. However, they use a monetary poverty line, so their results are not strictly comparable with those reported here.

Notice that health coverage is almost universal in Colombia because of the existence of a subsidized regime.

This result is consistent with Alfonsi et al. (2020), who also found effects in labor market outcomes without effects in entrepreneurship. One potential explanation consistent with Alfonsi et al. (2020) is that the certification provided by the program after completing phases 1 and 2 allowed participants to signal their skills.

Anderson et al. (2009) propose and test a model where female autonomy depends on access to the labor market, mainly when employment opportunities are outside husbands’ farms.

Elsayed and Roushdy (2017) also find similar large effects in employment outcomes for women’s empowerment intervention in Egypt, primarily driven by the informal sector. A key difference between their results and the ones reported in this paper is that their setting is mostly rural, whereas TTM operated in urban settings.

Austrian et al. (2020) and Buehren et al. (2017) also report large effects of empowerment intervention on savings. In the first case, the authors report an estimated coefficient of 19.3 percentage points for the treatment on the treated on the likelihood of saving (16% for the control mean at the baseline). In the second case, the authors estimate an effect of 2.8% percentage points (2% for the control mean at baseline). In the context of multifaceted programs for the poor, Banerjee et al. (2015) also find large effects for savings (156% increase with respect to the control mean).

According to the evaluation survey, 64% of the program’s participants reported having the same project or business activity supported by TTM in 2017. The other 36% of the program’s participants reported having failed projects. About 42% of the program’s participants with failed projects reported conflicts with other members of their associations as the main reason for project failure. On the other hand, about 44% reported issues related to lack of resources, credit, inputs, mentoring, and poor business environment as the main determinants for project failure.

I am not the first to find positive effects on savings but no effects on credit. Buehren et al. (2017) find a similar result in Tanzania. They rationalize this result by exploring the role of spillovers in participants’ social networks.

Notice that voting is voluntary in Colombia.

Banerjee et al. (2015) also finds large effects on political participation in their evaluation of several graduation programs for the poor. They do not find effects on voting, but document impacts on political party membership and attendance in village meetings.

This method provides additional confidentiality with respect to alternative elicitation methods, which is expected to create incentives for truthful reporting. See Blair et al. (2015) for a technical discussion. Cullen (2020) compares this technique against face-to-face questions and audio computer-assisted self-interviews. Using data from Nigeria and Rwanda, she finds that IPV rates are severely underestimated under the alternative methods. Once a list experiment is used, IPV rates increase by 100% in Rwanda and 39% in Nigeria.

It is important to emphasize that this result only captures a specific form of violence. Likewise, it is estimated using a linear regression for the matched sample. This particular choice is consistent with the brand of the matching literature that interprets this method as a pre-processor (Ho et al., 2007) but I am not aware of previous uses in the empowerment literature in the way presented here.

Using data for 31 developing countries, Bhalotra et al. (2020) find that an increase in the probability of employment for women is associated with a 3% increase in the probability of experiencing IPV.

I acknowledge the limitation of measuring social capital using membership in social organizations, although there are several examples in the literature. There is no consensus about what dimensions to take into account for social capital measurement but some of the proxies used in the past include trust, norms of reciprocity, engagement in public affairs, and participation in voluntary organizations.

Alternative parametric methodologies in the context of linear regressions are available to explore the sensitiveness of my main results. However, these methods are inappropriate for a fully non-parametric technique like matching. One common approach is based on the inclusion of additional covariates to explore how their inclusion changes the estimated effects in linear regressions. As emphasized by Oster (2019), one limitation of this approach is that coefficient movements alone are not sufficient statistics to approximate the role of omitted variables. It is also important to consider how much of the variance in the outcome is explained by the inclusion of covariates. In other words, when controls are included, omitted variable bias is proportional to coefficient movements, but only if these movements are scaled by the change in the R-squared. Oster (2019) offers a methodology to address these issues. This method can be complemented with an approach that selects these covariates using machine learning methods like double lasso (Urminsky et al., 2019) so I can address concerns about ad-hoc variable selection. I implemented these methods for monthly incomes in the final sample and found that my main results are robust to alternative sets of control variables. This result is robust even when the double lasso selects covariates. In all these cases, I found after implementing the methods in Oster (2019) that the unobservable variables should be between 5.68 and 8.01 times as important as the observables to obtain a null effect. Although these results depend on a parametric approach, the evidence is consistent with my sensitivity analysis. Results of these exercises are available upon request.

In Colombia, the Government of Atlantico developed a TTM’s sister program for men called “Transformate Tu Hombre” in 2013. The program has a similar structure as TTM and includes a training component designed to address gender stereotypes and IPV. To date, this program has not been evaluated.

References

Abadie A, Imbens G (2006) Large sample properties of matching estimators for average treatment effects. Econometrica 74(1):235–267

Abadie A, Imbens G (2008) On the failure of bootstrap for matching estimators. Econometrica 76(6):1537–1557

Abadie A, Imbens G (2011) Bias-corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 29(1):1–11

Abadie A, Imbens G (2016) Matching on the estimated propensity score. Econometrica 84(2):781–807

Alfonsi L, Bandiera O, Bassi V, Burguess R, Rasul I, Sulaiman M, Vitali A (2020) Tackling youth unemployment: evidence from a labor market experiment in Uganda. Econometrica 88(6):2369–2414

Anderson S, Eswaran M (2009) What determines female autonomy? Evidence from Bangladesh. J Dev Econ 90:179–191

Angelucci M, Heath R (2020) Women empowerment programs and intimate partner violence. AEA Papers and Proceedings 110:610–614

Arceneaux K, Gerber A, Green D (2006) Comparing experimental and matching methods using a large-scale voter mobilization experiment. Polit Anal 14(1):37–62

Ashraf N, Bau N, Low C, McGinn K (2020) Negotiating a better future: how interpersonal skills facilitate intergenerational investment. Quart J Econ 135(2):1095–1151

Aslam M (2013) Empowering women: education and the pathways of change. Background paper for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report

Austrian K, Soler-Hampejsek E, Behrman J, Digitale J, Jackson N, Bweupe M, Hewett P (2020) The impact of the Adolescent Girls Empowerment Program (AGEP) on short and long-term social, economic, education and fertility outcomes: a cluster randomized controlled trial in Zambia. BMC Public Health 20(349):1–15

Baird S, Ozler B (2016) Sustained effects on economic empowerment of interventions for adolescent girls: existing evidence and knowledge gaps. CDG Background Paper

Bandiera O, Buehren N, Burgess R, Goldstein M, Gulesci S, Rasul I, Sulaiman M (2020) Women’s empowerment in action: evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa. Am Econ J Appl Econ 12(1):210–259

Bandiera O, Burguess R, Das N, Gulesci S, Rasul I, Sulaiman M (2017) Labor markets and poverty in village economies. Quart J Econ 132(2):811–870

Banerjee A, Duflo E, Goldberg N, Karlan D, Osei R, Pariente W, Shapiro J, Thuysbaert B, Udry C (2015) A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: evidence from six countries. Science 348(6236):1260799

Bargain O, Boutin D, Champeux H (2018) Women’s political participation and intrahousehold empowerment:. IZA Discussion Paper Series 11534

Beaman L, Duflo E, Pande R, Topalova P (2012) Female leadership raises aspirations and educational attainment for girls: a policy experiment in India. Science 335(6068):582–586

Beath A, Christia F, Enikolopov R (2013) Empowering women through development aid: evidence from a field experiment in Afghanistan. American Political Science Review 107(3):540–557

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 57(1):289–300

Bhalotra S, Kambhampati U, Rawlings S, Siddique Z (2020) Intimate partner violence. The influence of job opportunities for men and women. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9118

Blair G, Imai K, Zhou Y (2015) Design and analysis of the randomized response technique. J Am Stat Assoc 110(511):1304–1319

Bott S, Guedes A, Ruiz-Celis A, Mendoza J (2019) Intimate partner violence in the Americas: a systematic review and reanalysis of national prevalence estimates. Pan Am J Public Health 43:1–12

Brooks W, Donovan K, Johnson T (2018) Mentors or teachers? Microenterprise training in Kenya. Am Econ J Appl Econ 10(4):196–221

Buehren N, Goldstein M, Gulesci S, Sulaiman M, Yam V (2017) Evaluation of an adolescent development program in Tanzania. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7961

Buller A, Peterman A, Ranganathan M, Bleile A, Hidrobo M, Heise L (2018) A mixed-method review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in low-and middle-income countries. World Bank Research Observer 33(2):218–258

Bursztyn L, Gonzales A, Yanagizawa-Drott D (2020) Misperceived social norms: women working outside home in Saudi Arabia. American Economic Review 110(10):2997–3029

Buvinic M, Furst-Nichols R (2016) Promoting women’s economic empowerment: what works? World Bank Research Observer 31(1):59–101

Buvinic M, O’Donnell M (2019) Gender matters in economic empowerment interventions: a research review. World Bank Research Observer 34(2):309–346

Campos F, Frese M, Goldstein M, Lacavone L, Johnson H, McKenzie D, Mensmann M (2017) Teaching personal initiative beats traditional training in boosting small businesses in West Africa. Science 357(6357):1287–1290

Chattopadhyay R, Duflo E (2004) Women as policy makers: evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica 72(5):1409–1443

CNC (2017) Informe de resultados y recomendaciones de la evaluacion de Transformate Tu Mujer. Producto 4. Centro Nacional de Consultoria

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Second ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Colson K, Rudolph K, Zimmerman S, Goin D, Stuart E, van der Laan M, Ahern J (2016) Optimizing matching and analysis combinations for estimating causal effects. Nature Scientific Reports 6:(23222)

Croke K, Goldstein M, Holla A (2017) Can job training decrease women’s self-defeating biases? Experimental evidence from Nigeria. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8141

Crump RK, Hotz VJ, Imbens GW, Mitnik OA (2009) Dealing with limited overlap in estimation of average treatment effects. Biometrika 96(1):187–99

Cullen C (2020) Methods matters. Underreporting of intimate partner violence in Nigeria and Rwanda. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9274

de Mel S, McKenzie D, Woodruff C (2008) Returns to capital in microenterprises: evidence from a field experiment. Quart J Econ 123(4):1329–1372

de Mel S, McKenzie D, Woodruff C (2012) One-time transfers of cash or capital have long-lasting effects of microenterprises in Sri Lanka. Science 335(6071):962–966

Deininger K, Jin S, Nagarajan H, Singh S (2020) Political reservation and female labor force participation in rural India. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9350

Dhar D, Jain T, Jayachandran S (2020) Reshaping adolescents’ gender attitudes: evidence from a school-based experiment in India. Mimeo

Diamond A, Sekhon J (2013) Genetic matching for estimating causal effects: a general multivariate matching method for achieving balance in observational studies. Rev Econ Stat 95(3):932–945

Doepke M, Tertilt M (2011) Does female empowerment promote economic development? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5714

Duflo E (2012) Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 50(4):1051–1079

Dupas P, Robinson J (2013) Savings constraints and microenterprise development: evidence from a field experiment in Kenya. Am Econ J Appl Econ 5(1):163–192

ECLAC (2020) Gender equality observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. https://oig.cepal.org/

Edmonds E, Feigenberg B, Leight J (2021) Advancing the agency of adolescent girls. Technical report, Darmouth College, University of Illinois, and IFPRI

Elsayed A, Roushdy R (2017) Empowering women under social constraints: evidence from a field intervention in rural Egypt. IZA Discussion Paper Series 11240

Fafchamps M, McKenzie D, Quinn S, Woodruff C (2014) Microenterprise growth and the flypaper effect: evidence from a randomized experiment in Ghana. J Dev Econ 106:211–226

Fonseca A (2019) Informe de empoderamiento economico de las mujeres en Colombia. Situacion actual y recomendaciones de politica, Equidad de la Mujer, Gobierno de Colombia

Fox L, Romero C (2017) In the mind, the household, or the market? Concepts and measurement of women’s economic empowerment. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8079

Ghani E, Kerr W, O’Connell S (2014) Political reservations and women’s entrepreneurship in India. J Dev Econ 108:138–153

Haushofer J, Ringdal C, Shapiro J, Wang X (2019) Income changes and intimate partner violence: evidence from unconditional cash transfers in Kenya. NBER Working Paper 25627

Heath R, Jayachandran S (2018) The causes and consequences of increased female education and labor force participation in developing countries. In: Averett S, Argys L, Hoffman S (eds) Oxford handbook of women and the economy. Oxford University Press

Ho D, Imai K, King G, Stuart E (2007) Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal 15(3):199–236

IDEA, PNUD, and ONU MUJERES (2019) Colombia: La hora de la paridad. IDEA and PNUD and ONU MUJERES

Imai K, King G, Stuart E (2008) Misunderstandings between experimentalists and observationalists about causal inference. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A 172 (Issue 2):481–502

Imbens G (2015) Matching methods in practice: three examples. J Hum Resour 50(2):373–419

Imbens G, Rubin D (2015) Causal inference for statistics, social, and biomedical sciences: an introduction. Cambridge University Press

Jayachandran S (2015) The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics 7:63–88

Jayachandran S (2020) Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment in developing countries. North-western University

Keele L (2010) An overview of rbounds: an r package for Rosenbaum bounds sensitivity analysis with matched data. Mimeo

Klasen S (2019) What explains uneven female labor force participation levels and trends in developing countries? World Bank Research Observer 34(2):161–197

Lafortune J, Riutort J, Tessada J (2018) Role models or individual consulting? The impact of personalizing micro-entrepreneurship training. Am Econ J Appl Econ 10(4):222–245

McKenzie D (2017) How effective are active labor market policies in developing countries? A critical review of recent evidence. World Bank Research Observer 32(2):127–154

McKenzie D (2021) Small business training to improve management practices in developing countries: re-assessing the evidence for “training doesn’t work’’. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 2021(2):276–301

McKenzie D, Stillman S, Gibson J (2010) How important is selection? Experimental vs. non-experimental measures of the income gains from migration. Journal of the European Economic Association 8(4):913–945

Milazzo A, Goldstein M (2019) Governance and women’s economic and political participation: power inequalities, formal constraints and norms. World Bank Research Observer 34(1):34–64

Montalvao J, Frese M, Goldstein M, Kilic T (2017) Soft skills for hard constraints: evidence from high-achieving female farmers. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8095

Mujeres ONU (2018) El progreso de las mujeres en Colombia. Transformar la economia para realizar los derechos, ONU MUJERES

ONU MUJERES (2020) Boletin estadistico: empoderamiento economico de las mujeres en Colombia. ONU MUJERES

Oster E (2019) Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: theory and evidence. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 37(2):187–204

Prennushi G, Gupta A (2014) Women’s empowerment and socio-economic outcomes. Impacts of the Andra Pradesh rural poverty reduction program. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6841

Rosenbaum P (2002) Observational Studies. Springer

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1985) Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 39(1):33–38

Roy T, Acharya R, Roy A (2016) Statistical survey design and evaluating impact. Cambridge University Press

Sanchez M (2018) Empoderamiento educativo de las mujeres. Situacion actual y lineas de politica, Equidad de la Mujer, Gobierno de Colombia

Schreiner M (2014) The process of poverty-scoring analysis. Available at http://www.simplepovertyscorerecard.com/

Sekhon J, Mebane W (1998) Genetic optimization using derivatives: theory and application to nonlinear models. Polit Anal 7:189–203

Sen A (1999) Development as freedom. Alfred Knopf

Sieverding M, Elbadawy A (2016) Empowering adolescent girls in socially conservative settings: impacts and lessons learned from the Ishraq program in rural upper Egypt. Stud Fam Plann 47(2):129–144

SMEG (2020) Transformate Tu Mujer. Secretaria de las Mujeres y la Equidad de Genero de la Gobernacion del Atlantico. https://www.atlantico.gov.co/index.php/secretarias/mujeres-y-equidad

Smith J, Todd P (2005) Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators? Journal of Econometrics 125(Issues 1–2):305–353

Upadhyay U, Gipson J, Ciaraldi E, Withers M, Fraser A, Prata N, Lewis S, Huchko M (2014) Women’s empowerment and fertility: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 115:111–120

Urminsky O, Hansen C, Chernozhukov V (2019) Using double-lasso regression for principled variable selection. University of Chicago

Vyas S, Watts C (2009) How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. J Int Dev 21(5):577–602

Woodruff C, McKenzie D (2012) Improving the productivity and earnings of women owned and/or managed enterprises in developing countries: What works? Available at http://www.womeneconroadmap.org/

World Bank (2012) Gender equality and development. World Development Report

World Economic Forum (2019) Global Gender Gap Report 2020. World Economic Forum

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. I thank editor Alfonso Flores-Lagunes, two anonymous reviewers, Darwin Cortes, Lorena Trujillo, and seminar audiences at the Universidad del Rosario and Universidad del Pacifico for helpful comments and advice. I especially thank Cristina Querubin and Carlos Castro as well as the CNC’s team for amazing field work. Juliana Aragon, Maria Paula Medina, and Julian Peña provided excellent research assistance.

Funding

Data collection for this project was funded by the National Planning Department (DNP) and carried out by the Centro Nacional de Consultoria (CNC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alfonso Flores-Lagunes.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is dedicated to the loving memory of my father, Humberto Zambrano. Te voy a extrañar mucho, papá.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Maldonado, S. Empowering women through multifaceted interventions: long-term evidence from a double matching design. J Popul Econ 37, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-00987-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-00987-z