Abstract

This paper investigates whether international migration increases the religious schooling of children in the home country. I find that migration by a household member from Bangladesh to a Muslim-majority country increases the likelihood that a male child in the household is sent to an Islamic school (madrasa). There is no significant impact on the likelihood of a male child’s madrasa enrollment if the household sends a member to a non-Muslim-majority country. Sending a household member abroad does not affect the likelihood of the household sending children to school at all; it only leads to reallocation toward Islamic schooling. The results are inconsistent with financial remittances underlying the effect of migration on religious schooling. Learning about the potential benefits of madrasa education may explain the results, but there are several weaknesses in the arguments in favor of this mechanism. A third potential mechanism is an increase in religiosity through migrants transferring religious preferences, but I cannot establish a causal relationship between international migration and migrant-sending households’ religiosity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

International migrants sent US $529 billion as foreign remittances to low- and middle-income countries in 2018—an amount that exceeded total foreign direct investment inflows to these countries (World Bank 2019).Footnote 1 International migrants can also transfer social remittances—that is, ideas, behaviors, identities, and social capital—from the host country (the migrant’s destination) to the home country (the migrant’s origin).Footnote 2 Through financial or social remittances, international migration can affect the behavior of members of migrant-sending households who remain in the home country. Ignoring such changes in the behavior of migrant-sending households can bias estimates of the socio-economic returns to international migration for the home country.

This paper addresses the question of whether international migration affects the preferences for religious schooling in the home country using data from Bangladesh. I use the 2010 round of the Bangladesh Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) to estimate the causal impact of a household that sends a migrant abroad on its likelihood of sending a child to an Islamic school (madrasa). Madrasas are a separate stream of schools in Bangladesh that specialize in Islamic education.Footnote 3 Madrasas have grown faster than any other institution in the education sector of Bangladesh (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2008). Bangladesh is a major migrant-sending country that received foreign remittances in 2018 equivalent to 5.4% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) (World Bank 2019).Footnote 4 These conditions make Bangladesh an ideal setting for this study.

I find that sending a migrant to a Muslim-majority country increases the likelihood of sending a male child to a madrasa, and reduces enrollment in non-madrasa schools. Sending a migrant to a non-Muslim-majority country does not have a statistically significant effect on madrasa enrollment. In addition, sending a migrant abroad does not affect whether children go to school at all, only which kind of school they attend.

I use the leave-one-out fraction of migrant-sending households in the primary sampling units (PSUs)—that is, the concentration of migrant-sending households among neighbors—as an instrumental variable. I follow Fruehwirth et al. (2019) in constructing the instrumental variable.Footnote 5 Essentially, I am leveraging on migrant networks, which previous studies have used as instrument for migration (Lokshin and Glinskaya 2009; McKenzie and Rapoport 2007, 2011). As there are two endogenous migration variables, I use two instrumental variables: the PSU-level leave-one-out fraction of households with a migrant in a Muslim-majority country and the PSU-level leave-one-out fraction of households with a migrant in a non-Muslim-majority country.

The identification assumption is that although the within-sub-district variation of the concentration of migrant-sending households among neighbors across PSUs is a strong predictor of a household’s likelihood of sending a migrant abroad, it does not directly influence a household’s choice of school for its children. I exploit the within-sub-district variation of the instrumental variables to causally identify the effect of a household sending an international migrant on the likelihood of that household sending a child to a madrasa.

Following the strategy of Fruehwirth et al. (2019), I decompose the exclusion restriction into three parts—an individual-specific component, a household-specific component, and a PSU-specific component—and show that the violation of the exclusion restriction through any of these components is unlikely. The violation of the exclusion restriction through the individual-specific component can occur only if there is a violation of the exclusion restriction through the household-specific component, since both migration and madrasa schooling are a household-level choice. The household-specific component might cause a violation of the exclusion restriction if a household makes a strategic change of location to facilitate external migration. Since it is costly to migrate and credit constraint limits the migration of households in Bangladesh (Bryan et al. 2014; Mendola 2008), such a strategic movement, and therefore, a violation of the exclusion restriction through household-specific component, is implausible. Finally, I use robustness tests to argue that a violation of the exclusion restriction through the PSU-specific component of the error term is unlikely. The PSU-specific component might compromise the identification assumption if PSU-level unobservables that vary within the sub-district are correlated with the instruments and outcomes. I find that the causal estimates are robust to the inclusion of the PSU-level leave-one-out average of the outcome and control variables, which suggests that PSU-level confounding variables are unlikely to compromise the validity of the exclusion restriction.

Since the exclusion restriction can be violated through other potential channels, I show that the findings are also robust to allowing for a minor relaxation of the strict exogeneity assumption following Conley et al. (2012). That is, my findings continue to hold if there is a very small correlation between the instruments and the error term in the second stage.

The increase in madrasa schooling as a result of migration intensifies over time. Using the 2016 round of the HIES, I find that migration increases the likelihood of madrasa schooling for female children, while the effect size for male children is larger than that of 2010. A rise in the school enrollment can partly explain why the madrasa education of female children increased (see also Asadullah and Chaudhury 2013). However, there is no change in the overall school enrollment of male children.

I next consider financial remittances, learning about potential benefits of madrasa education, and an increase in religiosity through migrants transferring religious preferences as potential mechanisms through which the effects of migration on religious schooling may operate. The results are inconsistent with the financial remittances mechanism. The effects of financial remittances can be separated into income effects and overcoming credit constraints. I rule out an income effect as the demand for madrasas has a lower income elasticity than that for non-madrasa schools. Credit constraints are unlikely because madrasas are cheaper than other schools (Al-Samarrai 2007; Asadullah and Chaudhury 2016; Asadullah et al. 2019). Moreover, households with migrants in non-Muslim-majority countries do not send their children to madrasas more, corroborating the inconsistency of financial remittances as the mechanism.

Another potential mechanism is a learning channel: migrants may learn that madrasa schooling improves migration opportunities. In particular, madrasas could be beneficial because they teach students Arabic language skills or impart other useful skills for work in the Persian Gulf. However, there are two weaknesses in the arguments in favor of this mechanism. First, the quality of education at madrasas in Bangladesh does not enable students to learn Arabic properly (Antara 2019; Bhuiyan 2018). Second, madrasa schooling is not a binding constraint to migrate to and work in the Persian Gulf, as manifested by migrants from non-Muslim countries like India, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka having a significant presence and earning potential in the region (Naufal 2011; World Bank 2019).

I provide suggestive evidence that one likely mechanism of international migration increasing madrasa schooling is a transfer of religious preferences by migrants, leading to an increase in the religiosity of migrant-sending households. However, I am unable to ascertain the existence of a causal link between international migration and migrant-sending households’ religiosity. Given the unique feature of madrasas of Bangladesh in focusing primarily on the teaching of Islamic theology, sending a child to a madrasa is a good indicator of a religious motivation. Only migrating to a Muslim-majority country causes an increase in madrasa schooling, indicating that a transfer of religious preferences from migrants to those countries may play a role in such increase. In addition, only migrant-sending households above the median income become more likely to send their male children to madrasas. Since the labor-market returns to madrasa schooling appear to be lower (Asadullah 2006, 2009; Berman and Stepanyan 2004; World Bank 2010), sending children to madrasas entails forgoing potential future income gains. Higher-income households can better afford this loss in future income, so the finding that they are the ones who send their sons to madrasas is consistent with the increase in religiosity mechanism. That an increase in household religiosity can potentially alter a household’s school choice is also consistent with existing evidence that a household’s religiosity affects its choice to send a child to religious schools (Cohen-Zada and Sander 2008; Sander 2005) and that people may choose religiosity over income-generating activity (Berman 2000).

There are two caveats to the arguments in favor of the transfer of religious preferences as a mechanism for the increase in madrasa schooling. First, an increased preference for madrasa education is not a direct measure of an increase in religiosity. Although choosing religious education can suggest increased religiosity, the latter includes other dimensions such as praying and fasting. I am not able to measure these other dimensions because of data limitations. Hence, I am not able to show an impact on these direct measures, which would provide stronger evidence that an increase in religiosity is a mechanism for my results. Second, changing religiosity is not easy and can take a long time.Footnote 6 The HIES is a cross-sectional dataset and there is no time dimension of the measurement of migration or the measurement of school choice. This dataset only allows me to measure any migration that has happened in the 5 years preceding the survey, which is not a very long time for religiosity to change. In addition, the HIES only allows me to construct a binary measure of school choice (madrasa or non-madrasa), and it is possible that households switch schools over time (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2013). Since I cannot measure an impact of migration on school choice over time, I can only show that migration affects the utilization of religious schools and cannot conclude that there is a causal impact on change in religiosity over time.

This paper makes major contributions to two different literatures. First, it contributes to the literature that examines the impact of international migration. International migration has direct effects on poverty reduction (Bertoli and Marchetta 2014), education (Antman 2011, 2012; Theoharides 2018), human capital formation (Dinkelman and Mariotti 2016), labor market outcomes (Binzel and Assaad 2011; Nguyen and Winters 2011), technology transfer (Kerr 2008), and political change Karadja and Prawitz 2019.Footnote 7 International migration increases migrants’ income (Clemens 2013; McKenzie et al. 2010), leading in turn to increased financial remittances to the home country (Yang 2008). Remittance income reduces poverty (Adams and Page 2005; Adams and Cuecuecha 2013) and child labor (Cuadros-Menaca and Gaduh 2019), and increases human capital formation (Ambler et al. 2015; Yang 2008) in the home country. This paper shows that with more migration, a home country’s choices of school types can be affected even when total enrollment is unchanged. If there is a substantial variation in the quality of different types of school, an emigration-induced change in preferences for a particular type of school can have implications for human capital production and future labor market outcomes.

Second, this paper contributes to the literature that studies changes in preferences, norms, and institutions in the home country through international migration. This paper establishes that international migrants affect the preferences for religious schools in the home country, a phenomenon that has received little attention in previous research. The existing literature shows that international migration facilitates the transfer of political institutions (Batista and Vicente 2011; Batista et al. 2019; Chauvet and Mercier 2014; Chauvet et al. 2016; Docquier et al. 2016; Spilimbergo 2009; Pfutze 2012; Mercier 2016; Tuccio et al. 2019), conservative gender norms (Tuccio and Wahba 2018),Footnote 8, and fertility norms (Beine et al. 2013; Bertoli and Marchetta 2015), and leads to the reduction of widespread social practices such as female genital mutilation (Diabate & Mesplé-Somps 2019). Having friends and family abroad is also positively associated with pro-social behavior (Nikolova et al. 2017). Lastly, this paper relates to the broader literature of migration-induced social remittances that includes studies that investigate migrants importing norms to the host country (Alesina et al. 2013; Fisman and Miguel 2007; Fernández 2011; Forrester et al. 2019).Footnote 9

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed background of Bangladesh’s madrasa education. Section 3 discusses the data and the descriptive statistics. Section 4 covers the empirical strategy and identification. The results and robustness checks are presented and discussed in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Madrasa education in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has made major progress in universally enrolling students in primary education, although retention remains a significant challenge for the country (Sabates et al. 2010). One unique feature of primary and secondary education in Bangladesh is that there are three major streams. First, there are Bengali-medium schools that follow the national curriculum. The public schools and a large number of private schools fall under this category. Second, there are some English-medium schools that largely follow a British curriculum. These are private schools and more expensive than any other type of school. And third, there are madrasas which are Islamic schools. Madrasas are not merely schools where a general curriculum is taught and is administered by religious authorities; rather these are religious schools where the core curriculum is the religion of Islam and the primary focus is on the teaching of the Quran, hadith, and other religious lessons. Essentially, madrasas operate as full-time schools to provide students education on faith and the primary learning outcome of these schools is to learn about Islamic theology. While the state has control over the curriculum of some madrasas, there are many on which the state does not have any control.

There are two kinds of madrasas in Bangladesh that provide primary education or above—Qawmi and Alia. Alia madrasas operate under the supervision of the state’s madrasa education board and follow the national curriculum set by the board.Footnote 10 The first Alia madrasa, known as the Calcutta Madrasa, was established in Bengal by the British colonial rulers to provide a model institution for Muslims that would teach both religious and secular subjects. Though the Calcutta Madrasa moved from Kolkata to Dhaka after the partition of India, it was not until the early 1980s that Alia madrasas began to spread in Bangladesh (World Bank 2010). The curriculum of Alia madrasas includes religious subjects (Quran, Islamic jurisprudence, and the Arabic languageFootnote 11) and secular subjects (the Bengali and English languages, math, science).

Qawmi madrasas, on the other hand, are mostly community based and operated by non-governmental entities. They depend on their own assets and charities for funding and follow their own curriculum. Qawmi madrasas began operating in South Asia during the Mughal periodFootnote 12 (World Bank 2010). After the British colonized the sub-continent in the \(18^{\mathrm {th}}\) century, these madrasas stopped receiving state support, turned away from teaching secular subjects, and focused only on the teaching of religion. They still exist in Bangladesh and often have an influence in politics and policy due to their organization and obedience to hierarchy. A Qawmi madrasa might offer non-religious teaching at its own discretion, which also depends on its ability to hire teachers. Degrees offered by Qawmi madrasas were not recognized by the state until 2017.Footnote 13

The share of madrasa enrollment is consistently higher at the secondary level (22%) than at the primary level (14%), suggesting either that households switch schools for their children to madrasas after primary education (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2013) or that the dropout rate at the secondary level is higher at non-religious schools. Between the years 1998 and 2014, enrollment in the registered secondary madrasas grew by 45% (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2016). Though a lack of supply of secular public schooling may have caused the spread of madrasas, there is no evidence to suggest that madrasas are currently more concentrated in regions where secular public schools are in low supply. There is a positive correlation between the number of Alia madrasas and the number of nonreligious public schools (World Bank 2010).

The pattern of enrollment in madrasas and the location of madrasas suggest that the decision to send a child to a madrasa in Bangladesh is unlikely to be due to supply-side factors. Instead, it is more likely to be influenced by demand-side factors such as poverty, cost, or preference. The majority of the madrasa-enrolled students comes from poor households (World Bank 2010). Most of the madrasa enrollment is at Alia madrasas (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2016). Madrasas are also cheaper than the non-madrasa alternatives (Asadullah et al. 2015). Qawmi madrasas are always cheaper than Alia madrasas. While the share of private cost for schools run by non-governmental organizations or the government can be less for primary education, Alia madrasas are cheaper than non-religious schools at the secondary level (Al-Samarrai 2007; Asadullah and Chaudhury 2016).

Madrasa students face at least two structural issues that adversely affect their labor market potential and put them in a disadvantaged position compared to their peers in non-madrasa schools. First, the madrasa curriculum limits a student’s opportunity to advance to university education. The Alia madrasa curriculum did not meet the prerequisites for admission in many secular disciplines at the university level until 2013 (Farhin 2017). The Qawmi madrasa curriculum does not allow its students to sit for many accredited university admission tests.

Second, the poor learning outcomes of madrasa students inhibit their university admission and labor market opportunities. Madrasa education has a negative correlation with labor market outcomes such as wage earning (Asadullah 2006, 2009). Though students can learn secular subjects at Alia madrasas, the learning outcomes of these students are worse than those of their counterparts at secular schools (World Bank 2010). The majority of Qawmi madrasas do not offer math at the secondary level, only three-fifths of Qawmi madrasas offer Bengali—the national language—and about 80% of the secular subject teachers are untrained. Lack of prerequisites and preparedness deprives madrasa students of the opportunity of studying more lucrative disciplines in universities and, consequently, they have poorer expected labor market outcomes. A large portion of graduates from Qawmi madrasas take the low-paying jobs of imams or maulavis in mosques and madrasas (Asadullah et al. 2019).

Madrasa graduates have a significantly higher fertility rate (Berman and Stepanyan 2004). Madrasa schooling is also negatively associated with positive attitudes towards income-earning women, lower and fixed desired fertility, and higher education for female children (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2010). Such perceptions may not necessarily help countries such as Bangladesh to alleviate poverty, to increase female empowerment, or even to curtail the threat of religious extremism.

It should be noted that madrasa students also face a lot of stereotypes that are not true. In Pakistan, madrasa students are more trusting towards non-madrasa students, while their trustworthiness is often under-estimated by those without a madrasa education (Delavande and Zafar 2015). It is possible that stereotype and stigma against madrasa students might influence their adverse labor market outcomes.

3 Data and descriptive statistics

For my primary analysis, I use the 2010 round of the HIES—a nationally representative survey of the population of Bangladesh to measure their living standards that the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics conducts every 5 years. To test whether my findings persist over time, I use the 2016 round of the HIES and estimate the same set of equations.

In total, 55,580 individuals from 12,240 households were interviewed for the 2010 round of the HIES, while 168,089 individuals from 46,075 households were surveyed in the 2016 round. Both of these rounds used a two-stage stratified random sampling strategy to select PSUs from the list of the population census enumeration areas. Twenty households were selected for interviews from each PSU, and all members of a household were interviewed.Footnote 14

The key independent variable of interest is whether the household has sent a migrant in a Muslim-majority country. In the migration module of the the HIES, each household is asked the following question: “Has any member of your household migrated, either within the country or abroad, during the last five years?”

If a household has sent at least one member to a Muslim-majority country in the previous 5 years, I consider that household to have a migrant in a Muslim-majority country. I refer to these households as \(M^1\) households. I use membership in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and having a majority Muslim population as criteria for a country being a Muslim-majority one (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation 2019). The Muslim-majority countries that the households in my sample have sent migrants to are Brunei, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

I can group migration to all Muslim-majority countries together without loss of generality. In all these countries, Islam is used in state affairs—the legal system either is entirely guided by the sharia (e.g., Saudi Arabia) or co-exists with the common law but Muslims must abide by sharia law (e.g., Malaysia). In addition, these countries are also similar in that in none of these countries does a separate religious education stream exist as in Bangladesh. Though my analysis would be much stronger if I could show results for each Muslim-majority country separately when migration to all Muslim-majority countries is considered separately, the sample sizes of migrant-sending households for each country become very small, which will cause a lack of statistical power. Therefore, to do a meaningful analysis, I group together all migration to a Muslim-majority country.

Similarly, I consider a household to have a migrant in a non-Muslim-majority country if that household has sent a migrant to a non-Muslim-majority country, and I refer to those households as \(M^2\) households.Footnote 15 The non-Muslim-majority countries that the households in my sample have sent migrants to are: Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, the UK, and the USA.

Table 1 reports the destination countries of migrants from Bangladesh. A majority (83%) of Bangladeshi migrants go to Muslim-majority countries. Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Malaysia are the top three destinations of Bangladeshi migrants.

There are three key limitations to this approach to measuring migration. First, the HIES does not include the frequency of a household member’s migration. As a result, I cannot know if the reported migration was the first time that individual had migrated or whether that person had migrated before as well. Second, although the questionnaire asks whether any currently residing household member has returned from abroad within the last 5 years after living there for at least 6 months, it does not include information on when the migrant has returned. Neither does it collect information about the destination or length of the migration of that returning member. This prevents me from analyzing the effects of return migration. Third, I do not know whether an individual has switched countries since migrating. I have to rely on the last reported country of migration to construct the type of country (i.e., Muslim-majority/non-Muslim-majority) variables. Because of these limitations, I can only identify the total effect of any migration—first time or repeat—that has happened in the previous 5 years, irrespective of whether the migrant has returned home or not.Footnote 16

As the primary outcome of interest in this paper is the likelihood that a household sends a child to a madrasa for schooling, I restrict my analysis to children aged 5 to 18 years. I also focus on the likelihood of a household sending at least one child to a madrasa in order to understand the household-level effects. I consider a household to be a madrasa-sending household if at least one child of the household goes to a madrasa. For the household-level analysis, I restrict my sample to households that have at least one child. These restrictions reduce my sample to 9178 households and 18,063 children in the 2010 round, and to 56,439 children in 32,204 households in the 2016 round of the HIES. In the 2010 HIES, there are 1578 children from 758 \(M^1\) households and 357 children from 178 \(M^2\) households, while there are 3707 children from 2114 \(M^1\) households and 863 children from 469 \(M^2\) households in the 2016 HIES.

One limitation of my measurement of the outcome variable is that I cannot identify whether a child has switched from a madrasa school at the primary level to a non-madrasa school at the secondary level (or vice versa). The HIES does not collect information on education history. In Bangladesh, a considerable fraction of children switch from non-madrasa schools to madrasa schools after the completion of primary school (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2013). I cannot investigate such dynamics and have to rely on the binary construct of being currently enrolled at a madrasa or at a non-madrasa school.

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the key outcome variables in the 2010 HIES.Footnote 17 About 60% of the school-aged children attend school.Footnote 18 About 5% of the children from \(M^{1}\) households attend madrasas, compared to four percent of children from non-migrant-sending households. In addition, \(M^{1}\) households are more likely to send at least one of their children to a madrasa than are non-migrant-sending households. Eight percent of \(M^{1}\) households send at least one child to a madrasa, while 6% of households without a migrant in a foreign country send a child to a madrasa. There is no difference between the likelihood of a child from an \(M^2\) household going to a madrasa (4%) and the likelihood of a child from a non-migrant-sending household going to a madrasa (4%). The likelihood of an \(M^{2}\) household sending at least one child to a madrasa (5%) is slightly lower than that of a non-migrant-sending household doing so (6%).

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics for several individual- and household-level variables.Footnote 19 In the estimation sample, 52% of the children are male and the average age is 11.26 years. About two-thirds of the households (64%) live in rural areas. The majority of the households (88%) are headed by a Muslim, likewise the majority (87%) are headed by a male. More than half of the household heads (52%) do not have any formal education. Very few households (2%) have an adult over 23 years of age who went to a madrasa. This alludes to the fact that the increase in madrasa education is a recent phenomenon, correlated with the rise in school enrollment in Bangladesh. Roughly 1% of the households have a member who had returned from abroad in the last 5 years after living there for at least 6 months.Footnote 20

4 Empirical strategy

4.1 Estimation method

Let i indicate a child, h denote household, p refer to PSU, and s indicate sub-district. Then the key equation of interest is:

In Eq. 1, \(Y_{ihps}=1\) if child i of household h in PSU p of sub-district s goes to a madrasa, and 0 otherwise. \(M^{1}_{hps}\) is an indicator for whether household h in PSU p of sub-district s has a member who migrated to a Muslim-majority country in the last 5 years, where \(M^{1}_{hps}\in \{0,1\}\). Similarly, \(M^{2}_{hps}\) is an indicator variable of whether household h in PSU p of sub-district s has a member who migrated to a non-Muslim-majority country in the last 5 years, where \(M^{2}_{hps}\in \{0,1\}\). \(X_{ihps}\) denotes individual-level control variables, and \(H_{hps}\) refers to household-level control variables. The error term is denoted by \(\xi _{ihps}\), and \(\alpha _s\) represents sub-district-level fixed effects. The key parameters of interest are \(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _2\). Households sending no migrants abroad (i.e., \(M^{1}_{hps}=0\) and \(M^{2}_{hps}=0\)) form the comparison group.Footnote 21

In order to examine whether the individual-level effects reflect a change in preferences for households who would not send any child to a madrasa otherwise, I also perform a household-level analysis. The outcome variable for the household-level analysis is constructed as follows: \(Y_{hps}=1\) if household h in PSU p of sub-district s sends at least one child to a madrasa, and 0 otherwise. Hence, the equation of interest for the household-level analysis becomes:

A major concern in estimating these equations is that international migration is not a random phenomenon, that is, \(cov(M^{j}_{hps} ,\xi _{ihps})\ne 0\) or \(cov(M^{j}_{hps} ,\zeta _{hps})\ne 0\), where \(j\in \{1,2\}\). The household-level decision of sending a migrant abroad may depend on a number of confounding observable and unobservable factors. For example, a household’s decision to migrate to a Muslim-majority country might be influenced by that household’s preference to send a child to a madrasa, thus creating a reverse causality problem.

Moreover, ordinary least squares (OLS) will produce biased estimates due to omitted variables bias. The wealth of the household cannot be included in the estimation, while its exclusion can create further endogeneity issues. The wealth of a household can have a simultaneous relationship with the school that a child of that household attends. A potential change in the wealth of the household can influence the attainment of education. With an increase in wealth from migration, households might decide to send their children to school (that is, the extensive margin of schooling). Wealthier households might also choose to send their children to more expensive schools. On the other hand, the returns to education of a child would affect household wealth. Hence, there is a simultaneous relationship between schooling and household wealth. In addition, while a household’s decision to send a migrant abroad may depend on the wealth of that household (McKenzie and Rapoport 2007), migration itself can improve the wealth of the household. Therefore, wealth cannot be included in the equation. But exclusion of wealth also introduces omitted variable bias into the estimation strategy. In addition to wealth, the level of education of the migrant and intra-household power dynamics can act as confounding factors for migration and school choice.

To overcome the endogeneity of migration and schooling, I use an instrumental variables method. I use the leave-one-out fraction of migrant-sending households in a PSU as the instrumental variable. For household h, a leave-one-out fraction of migrant-sending households in PSU p is calculated by dividing the sum of the total number of migrant-sending households in that PSU except household h by the total number of households in that PSU except for household h. As there are two endogenous variables here, I need to use two instrumental variables. The instrumental variable for each type of migrant-sending household is a leave-one-out fraction of that type of migrant-sending household in the PSU. Formally, for a household h of migration type \(M^j\) in a PSU p of sub-district s, the instrumental variable is defined as:

Here, \(N_{ps}\) is the total number of households in the PSU. The subscript p(h) refers to the PSU-level average without household h.

The fraction of migrant-sending households in a PSU represents the transnational network of external migrants in the neighborhood. Such a network of external migrants from the neighborhood can help potential migrants in the source country to migrate (Lokshin and Glinskaya 2009; Munshi 2003; McKenzie and Rapoport 2007). A network of migrants increases access to information and can reduce uncertainty regarding migration. Therefore, the existence of such a network would facilitate external migration.

I exploit the within-sub-district variation of the leave-one-out fraction of migrant-sending households among the neighbors (in this case, PSUs) to identify the causal effect of migration on sending a child to a madrasa. Since migration is a binary variable, there are only two values for each of the instrumental variables within each PSU—one value if the household is a migrant-sending household, and another if not. Hence, most of the variation in the instrumental variables comes from between PSU variation. Table A1 in Appendix A reports the descriptive statistics of the instrumental variables.

In this instrumental variable framework, there are two first-stage regressions:

The second stage is:

Here, \(\widehat{M^{1}}_{hps}\) and \(\widehat{M^{2}}_{hps}\) are the predicted values from the first-stage estimation.Footnote 22 Thus, \(\beta _{1}\) and \(\beta _{2}\) from a two-staged least squares (2SLS) estimation are consistent estimates of the parameters of interest.Footnote 23 As the sampling strategy involved picking PSUs randomly and then interview randomly chosen households, I cluster standard errors at the PSU level—following Abadie et al. (2017).

The estimates of \(\beta _{1}\) and \(\beta _{2}\) are local average treatment effects (LATE)—the treatment effect of the compliers (Imbens and Angrist 1994). That is, I identify the treatment effect of the households that would not otherwise send migrants abroad but do so when the fraction of migrant-sending households in the neighborhood increases.

In this individual-level estimation, I include the following control variables: age (in years) and age squared, whether any adult above 23 years of age went to a madrasa, whether the household head is a Muslim, whether the household has any member who returned from abroad within the last 5 years after living there for at least 6 months, the level of education of the household head, and sub-district-level fixed effects. I include all but the individual-level controls (age in years and age squared) as control variables for the household-level analysis.

4.2 Identification

I exploit the variation in the concentration of migrant-sending households across PSUs within the same sub-district to isolate exogenous variation in a household’s decision to send a migrant abroad. The underlying assumption is as follows: while within sub-district variation in the concentration of migrant-sending households across PSUs is a strong predictor of the likelihood of household h being a migrant-sending household, it does not directly affect the household’s schooling decision for a child. Formally, my identification relies on the following assumptions:

Having many migrant-sending households in a neighborhood establishes a network for aspiring migrant-sending households. A network of migrant-sending households would make information more available and accessible. As information is a key constraint for international migration (Beam 2016; McKenzie et al. 2013), access to information should increase the probability of migration from the neighborhood.

Consequently, the likelihood of a household sending a migrant to a Muslim-majority country should increase in \(Z^{1}_{p_{(h)}}s\). This hypothesis is tested by obtaining a statistically significant \(\hat{\lambda _1}\) from Eq. 3. Similarly, whether the likelihood of migration to a non-Muslim-majority country is increasing in \(Z^{2}_{p_{(h)}}s\) can be tested by obtaining a significant \(\hat{\gamma _2}\) from Eq. 4.

Table 4 reports the results of the estimation of the first stage. A household’s own probability of sending a migrant to a Muslim-majority country increases by 6.8 percentage points when the proportion of households in the neighborhood with a migrant in a Muslim-majority country increases by 0.1. When there is a similar increase in the proportion of households with a migrant in a non-Muslim-majority country, the probability of a household to send a migrant in those countries increases by 4.1 percentage points. The strong and statistically significant estimates of the instrumental variables for both types of migrant-sending households imply that the instrumental variables satisfy the relevance condition (assumption A1).Footnote 24

Using the weak instrument test of Olea and Pflueger (2013), I find that the Olea-Pflueger F-statistics for \(Z_{p(h)s}^1\) and \(Z_{p(h)s}^2\) are higher than the critical values for 5% and 10%, respectively, of the worst-case bias from a weak instrumental variable. Therefore, I can rule out that the instrumental variables are weak.

One major threat to identification is the violation of assumption A2—that is, the exclusion restriction—as the validity of the causal estimates relies on satisfying these assumptions. It is likely that the concentration of migrants in the neighborhood directly affects a household’s likelihood to send at least one child to a madrasa, rendering estimates inconsistent. To tackle this, I exploit the plausibly random within sub-district variation in of concentration of migrants across PSUs. I assume that after controlling for pre-determined household- and individual-level characteristics, within-sub-district variation in the concentration of migrant-sending households across PSUs does not correlate with the household’s unobservable type. However, unlike the relevance condition, there is no direct statistical method to test this assumption.

To address the concern that the within-sub-district variation of migrants across PSUs may violate the exclusion restriction, I divide the residuals from the second stage into three parts following the strategy of Fruehwirth et al. (2019): individual-specific components (\(u_{ihps}\)), household-specific components (\(v_{h(i)ps}\)), and PSU-specific components (\(\nu _{p(h)s}\)) that include PSU-level direct effects on school choice or other PSU-level unobservables. As a result, the error term can be written as \(\epsilon _{ips}=u_{hps}+v_{h(i)ps}+\nu _{p(h)s}\). Assumption A2 can be written as follows:

For the estimates to be consistent, the following conditions need to be true:

Condition (6) or (7) is violated when an individual or a household can select into PSUs based on unobservables which are related with both madrasa education and migration. Such selection will not be addressed by sub-district-level fixed effects. Since a systematic change of PSU by a child is not a practical reality, we can assume that such violation would occur only through a systematic change of PSU by households. Moreover, both the key independent variable—whether a household sends a migrant abroad—and the key outcome variable—the decision of sending any child to a madrasa—are household-level decisions. Therefore, for all the intents and purposes, I can argue that condition (6) will not be violated if (7) is not violated.

For a violation of \(Cov\left( Z^{j}_{p_{(h)}s},v_{h(i)ps}\right) =0\), a household would have to systematically change PSU based on the fraction of migrants there are or based on anything that is correlated with the fraction of migrants and choice of school type. In other words, to migrate internationally, a household can make the strategic decision to migrate internally to PSUs with more migrant-sending households. Learning about migration opportunities certainly induces households to make strategic choices (Shrestha 2017).

However, such strategic movement is unlikely in this setting because of the cost of migration. Both internal and international migration are expensive endeavors. Credit constraints restrict the ability of households to send migrants abroad (Mendola 2008). Internal migration also is often undertaken by households with access to more income (Munshi & Rosenzweig 2016). In addition, internal migration in Bangladesh is principally constrained by a lack of credit rather than by a lack of information (Bryan et al. 2014). International migration being much more expensive than internal migration, it does not seem plausible that Bangladeshi households would strategically move into different PSUs that would facilitate international migration rather than migrating to areas with higher wage jobs. Hence, I do not consider that such a violation of condition (7) to be a likely threat.

Condition (8) can be violated if there are PSU-level variables that correlate with both the outcome variable and the instrumental variables. This is a concern if there are PSU-level observables or unobservables that affect sending a child to a madrasa and also correlate with the fraction of migrants in the PSU. One way to alleviate this concern is to show that the causal estimates do not change when PSU-level leave-one-out average of outcome variables and control variables are included in the main specification. In Section 5.2, I show that the estimates do not change when PSU-level observables are controlled for. If the estimates were driven by unobservable PSU-specific factors, then the inclusion of these additional controls would significantly change my results. Thus, I argue that a violation of condition (8) is not highly likely either and, therefore, the validity of my identification is not threatened by the exclusion restriction not being satisfied.

5 Estimation and discussion

5.1 Discussion of the main results

The primary equation that I estimate is Eq. 5:

Results from estimation of this equation—presented in Table 5—show that a child from a household with a migrant in a Muslim-majority country (\(M^1\)) is six percentage points more likely to go to a madrasa. This result is statistically significant at the 10% level. A six percentage points increase is equivalent of a 150% increase in the probability compared to the sample mean. The effect on the probability that a child from a household with a migrant in a non-Muslim-majority country (\(M^2\)) goes to a madrasa is negative in magnitude, but not statistically significant.

Omitted variables of the naive OLS estimates—such as household wealth, aspiration of earning a higher income, and skill and ability of the migrant—would positively correlate with the likelihood of migration, but are likely to have a negative correlation with the preference for a school that has a relatively lower returns (Asadullah 2006, 2009; World Bank 2010). Thus, the naive estimates would likely suffer from a downward bias. Indeed, the naive OLS estimates are small in magnitude and insignificant, while generally, the 2SLS estimates are larger than OLS estimates and statistically significant for male children. The larger magnitude of the 2SLS estimates than OLS verifies that the naive estimates are biased downward—consistent with the expected direction of bias.

This result is driven by the causal impact of a household sending a member to a Muslim-majority country on the probability of that household sending a male child to a madrasa. A male child from an \(M^1\) household is 10.8 percentage points more likely to be sent to a madrasa. This is statistically significant at the 5% level. In other words, if a member migrates to a Muslim-majority country, it increases the household’s probability to send a male child to madrasa by 2.5 times of that of the sample mean. As with the estimates for a child of any sex, the magnitude of the impact of having a migrant in a non-Muslim-majority country on the likelihood of male child being sent to madrasa is negative and statistically insignificant. The estimates of the effects of being an \(M^1\) or \(M^2\) household on the likelihood of sending a female child to a madrasa are very small (0.003 and 0.008, respectively) and statistically insignificant.

\(M^1\) households send some of their children to madrasas whom they would have otherwise sent to non-madrasa schools had there been no migration. The results presented in Table 6 show that having a migrant abroad does not have a significant impact on increasing enrollment to school. In addition, the direction of the effect of having a migrant in a Muslim-majority country on the likelihood of sending a male child to a non-madrasa school is negative (−0.136)—though, due to relatively large standard errors (0.096), the effect is not significant even at the 10% level of significance. However, this result suggests that the increase in the likelihood of madrasa schooling for male children is due to households switching from non-madrasa schools to madrasas, not because of a general increase in school enrollment.Footnote 25

Having a migrant in a Muslim-majority country also affects whether the household sends at least one child to a madrasa (10.2 percentage points increase), and, similarly to individual-level effects, this is driven by the increased likelihood of the household sending at least one male child to a madrasa (12.9 percentage points increase). Panel A of Table 7 reports the results for this estimation. The household-level analysis was conducted only on households with children. The sex-specific household-level results are similarly estimated using only households that have at least one child of that particular sex.

Since the dependent variable here is whether the household sends at least one child to a madrasa, the household-level effects indicate that sending a migrant abroad can also increase madrasa schooling at the extensive margin. That is, migration of a member of the household to a Muslim-majority country causes a household to send at least one child to a madrasa, while that household would not have sent any child to a madrasa in absence of sending a member abroad. As there is no increase in schooling as a whole, this increase at the extensive margin further corroborates that the effect I find is a switching effect.

Though households are switching some of their children to madrasas from non-madrasa schools because of migration, they are not doing this for all of their children. The results presented in Panel B of Table 7 show that having a migrant abroad does not have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of sending at least one child to a non-madrasa school. The effect of having a migrant in a Muslim-majority country on the likelihood of sending at least one male child to a non-madrasa school has a sizable but imprecise negative estimate. Similarly, having a migrant in a non-Muslim-majority country has a statistically insignificant but sizable positive estimate for the effect on sending at least one male child to a non-madrasa school. There is no impact when I look at the likelihood of sending at least one female child to a non-madrasa school.Footnote 26

These results establish that households that have migrants in Muslim-majority countries switch schools from non-madrasa schools to madrasas for some of their male children but not for all of them.Footnote 27 As indicated above, the existing literature suggests that madrasa students have worse learning outcomes (World Bank 2010) and lower returns to education Berman and Stepanyan 2004 than non-madrasa students. There is also a negative relationship between madrasa education and wage income (Asadullah 2006, 2009). This is also corroborated by the fact that madrasa-educated students cannot apply for good university degrees and, therefore, cannot get good jobs.

I estimate the relationship between madrasa education and labor market outcomes for the working-age population—that is, for all persons aged 15 to 64 years. I explore the relationship between madrasa education and two key outcome variables—labor force participation and current employment. Table 8 reports the results of the estimation. I find that madrasa education has a significant negative relationship with these labor market outcomes of the male working-age population. The likelihood of labor market participation by males decreases by 3.5–4 percentage points, depending on the specification. The employment rate also declines by about 3.5–4.2 percentage points. The reduction of labor force participation and current employment indicates that madrasa educated males are relatively worse off than the non-madrasa-educated males in terms of their labor market outcomes.

The net welfare effects of this increase in madrasa education are ambiguous. As the primary focus of madrasas is the study of religion, having a madrasa education could also increase children’s religiosity. Religiosity has significant socio-economic effects. For instance, religiosity positively affects both income (Bryan et al. 2020) and educational attainment (Gruber 2005). Religiosity can also have adverse effects on labor supply (Berman 2000), and increases an individual’s tendency to discriminate (Lavy et al. 2018). The negative relationship between madrasa education and learning outcomes and labor market outcomes suggests that a systematic increase of madrasa education might adversely influence the human capital development of Bangladesh.Footnote 28 External migration is extremely important due to the large welfare gains it can generate (Clemens 2011). If the migration-induced increase in madrasa schooling leads to an unaccounted for social costs, then the calculated returns of external migration would be overestimated. Conversely, if madrasa schooling leads to unmeasured benefits, then the returns to migration would be understated. In either scenario, it is likely that estimates that focus solely on the effects on earnings for migrants are mis-calibrated.

5.2 Robustness checks

5.2.1 Validity of identification

To tackle the concern that \(Cov(Z^{j}_{p_{(h)}s},\nu _{p(h)s}) =0\) can be violated, I plug the PSU-level leave-one-out average of outcome and control variables into the main specification and re-estimate the results. The control variables I select are: whether the household has an adult aged 23 years or older who went to a madrasa, whether the household head was a Muslim, whether the household has a member who returned from abroad, and the level of education of the household head. By including PSU-level leave-one-out average of control variables, I am controlling for other factors that might be associated with neighborhood-level migration and school choice. I also include the leave-one-out mean of the outcome variable, that is the fraction of children in the PSU that attends a madrasa. If households with a migrant in a Muslim-majority country live in a locality that prefers religious schools more to begin with, then this difference in pre-migration preferences of the neighborhood may explain the difference in schooling decisions. In that case, the inclusion of the neighborhood-level leave-one-out average of incidence of madrasa schooling would explain away the causal relationship that I find. Then I estimate the equation with both the pre-determined neighbor characteristics and outcomes. I also include the distance of the nearest gender-specific madrasa from the PSU (when madrasas are situated in the same PSU as the household, the distance is coded as 0) to test whether the supply of madrasas can explain the causal results I find. Table 9 reports the results of the estimation.

I find that an inclusion of the neighbor characteristics does not change the results, though their magnitude increases slightly (11.4 percentage points). When I include only the average of the neighbors’ outcome, again, the magnitude is smaller (8.9 percentage points)—but qualitatively, the results remain the same and they remain significant.Footnote 29 When I include both the neighbor characteristics and the neighbor outcome, the estimates (10.1 percentage points) are almost the same as that of the baseline results (10.8 percentage points). When I include the distance to the nearest gender-specific madrasa, the estimate is again almost the same (10.0 percentage points). As the addition of these additional controls cannot explain away the main results, this reduces the concern of PSU-level confounding variables violating condition \(Cov(Z^{j}_{p_{(h)}s},\nu _{p(h)s})=0\) and threatening the validity of the identification strategy. Therefore, this further supports that the estimates I find can be considered causal.Footnote 30

It is possible that there are other reasons that violate the exclusion restriction that I have not thought of. Hence, I check whether my results are robust to a relaxation of the strict exogeneity conditions following the methodology laid out by Conley et al. (2012). The methodology of Conley et al. is as follows: relax the assumption of instrument variables being strictly exogenous and assume that the instrumental variables enter the second stage estimation. I relax the assumptions \(Cov(Z^{1}_{p_{(h)}s},\eta _{ihps})=0\) and \(Cov(Z^{2}_{p_{(h)}s},\psi _{ihps})=0\) and assume that \(Z^1\) and \(Z^2\) enter the second stage with coefficients \(\beta _{Z^{1}}\) and \(\beta _{Z^{2}}\), respectively. I compute the bounds of the consistent values of the coefficients of \(M^1\) and \(M^2\) by making assumptions about the values of \(\beta _{Z^{1}}\) and \(\beta _{Z^{2}}\).

I follow Nunn and Wantchekon (2011) and Azar et al. (2020) to implement this methodology. I regress madrasa schooling on the household-level migration variables, the instrumental variables, and the full set of control variables used in the preferred specification. The coefficients of the instrumental variables from this estimation are taken as upper (lower) bound of the values of \(\beta _{Z^{1}}\) and \(\beta _{Z^{2}}\) if the coefficient is positive (negative), while 0 is assumed to be lower (upper) bound.

As my primary result is that migration to a Muslim-majority country increases the probability of madrasa schooling, I focus on the effects of \(M^1\) when I assume plausible exogeneity of \(Z^1\). The coefficient of \(Z^1\) is 0.067 in the reduced form, where the outcome variable is regressed on all the regressors and the instrument variables. Hence, I assume that the upper bound of \(\beta _{Z^{1}}\) is 0.067 and the lower bound is 0.Footnote 31 The results of this computation are reported in Table 10.

The confidence interval of the coefficient of the primary variable of interest, that is, a household having a migrant in a Muslim-majority country, includes 0 under the assumed bound of \(\beta _{Z^{1}}\). The maximum value of \(\beta _{Z^{1}}\) for which the coefficient for the individual-level effect on the schooling of male children does not include 0 (I refer to it as \(\beta _{Z^{1}_{max}}\)) is approximately 0.012, which is roughly 6.3 percent of the upper bound of \(\beta _{Z^{1}}\) (0.19). This means that my main results are robust for a minor violation of the strict exogeneity assumption.

5.2.2 Intertemporal external validity

To verify whether the results hold over time, I estimate my main results using the 2016 HIES, which was collected based on a new sample. If the results of the 2010 HIES and the 2016 HIES were inconsistent, that would raise doubts about the validity of the findings.Footnote 32

Table 11 presents the results of the estimation of my main specification (Eq. 5) using the 2016 round of the HIES. The new estimates show that having a migrant in a Muslim-majority country increases the likelihood of sending a child to a madrasa by 15.4 percentage points, as opposed to six percentage points in 2010. In 2016, the point estimate of the effects on the likelihood of sending a male child to a madrasa is 0.147, as opposed to 0.108 from 2010. Moreover, the probability of sending a female child to a madrasa also increases by 4 times the sample mean in 2016.Footnote 33 Migration to a non-Muslim majority country, similar to the results I find using the 2010 HIES, does not have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of sending any child or a child of a particular gender to a madrasa.

To further verify whether the results are intertemporally consistent, I use the 2016 HIES to estimate the effects of migration on school enrollment and on non-madrasa schooling. The results from Appendix Table A6 show that migration to a Muslim-majority country reduces the probability of a male child going to a non-madrasa school by 13.8 percentage points—a 17% reduction compared to the sample mean. Migration to a non-Muslim-majority country, on the other hand, does not have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of non-madrasa schooling. Results from the household-level analysis using the 2016 HIES—presented in Appendix Table A7—are qualitatively similar to the results that I find from using the 2010 HIES. The only meaningful difference is that having a migrant in a Muslim-majority country reduces the likelihood of sending at least one male child to a non-madrasa school. This implies that with the passage of time, migrant-sending households become more likely to send all of their male children to madrasas.

The analysis using the 2016 HIES shows that the intensity of the causal impacts has increased over time. The effects on sending male children to madrasas persist and the point estimate becomes larger. In addition, additional effects on sending female children to madrasas appear to manifest over time. A general increase in female education can partially explain the increase in madrasa schooling for female children. However, there is no general increase in the enrollment of male children. Therefore, the increase in madrasa schooling for male children is not due to an increase in overall male enrollment.

5.3 Mechanisms

I explore three potential mechanisms through which international migration could causally increase the demand for religious schooling—financial remittances, learning about the potential benefit of madrasa schooling, and an increase in religiosity through the transfer of religious preferences.Footnote 34 I show that the results are inconsistent with the financial remittances mechanism. I explain how the learning channel effect can potentially explain the results, along with the reasons that weaken the case for this mechanism. I find suggestive evidence that the transfer of religious preferences is a potential mechanism for my results, but I cannot provide direct evidence for changes in religiosity.

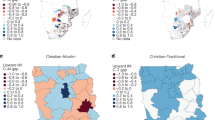

I can separate the financial remittances effect into two parts—income effect and reduced credit constraint. If the demand for madrasa has high income elasticity, then the additional household income generated from the financial remittances received from migrants might increase madrasa education. Here, the choice of school is discrete—madrasas or non-madrasa schools. Hence, if there is a high relative income elasticity of madrasa education, then madrasa schooling might increase with migration to Muslim-majority countries. However, in the absence of migration, madrasa education has a lower income elasticity than non-madrasa options. In Figs. 1 and 2, I plot the sex-wise probability of a child from a non-migrant-sending household to go to a madrasa for different total household income and asset, respectively. The slope for sending a child to a madrasa is lower than the slope for sending a child to a non-madrasa school. This suggests that given the two choices, madrasa schooling does not have the higher income elasticity. Thus, I can rule out the income effect mechanism.

The probability of a child from a non-migrant-sending household attending school in relation to the household’s total income. The figure shows the relative change in the probability of a child from a non-migrant-sending household attending any (a madrasa or a non-madrasa) school with the change in the inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) transformation of the total income of the household (in Bangladesh Taka). Source: Author’s calculations based on the 2010 HIES

The probability of a child from a non-migrant-sending household attending school in relation to the household’s total assets. The figure shows the relative change in the probability of a child from a non-migrant-sending household attending any (a madrasa or a non-madrasa) school with the change in the inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) transformation of the total asset of the household (in Bangladesh Taka). Source: Author’s calculations based on the 2010 HIES

The mechanism of a reduction of credit constraints would work in the following way: a household, in spite of the willingness to send a child to a madrasa, cannot do so due to not having the means. In the absence of migration the said household would send the child to a non-madrasa school, as otherwise there would have been an increase in school enrollment. If the household’s credit constraint is reduced because of financial remittances sent by the migrant, the household decides to send the child to a madrasa.

There are two reasons why this mechanism is inconsistent with the data. First, madrasas in Bangladesh are less expensive than non-madrasas. Qawmi madrasas are less expensive than Alia madrasas, and non-madrasa schools might be much more expensive considering all the outside tutoring fees that a household might have to pay. Admittedly, non-madrasa schools might be a less expensive option than madrasas at the primary level, but at the secondary level madrasas are less expensive than non-madrasa schools (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2016; Al-Samarrai 2007). To test whether the results are driven by primary school students, I estimate the main specification by dividing the sample according to age group. Appendix Table A8 reports the result. Since different children might start primary school at different ages, I split the sample in different ways. It shows that the point estimates are larger and more precise for the age group at which students would go to secondary schools, suggesting that the causal impact is much stronger for madrasa schooling at the secondary level. Hence, the data are inconsistent with the hypothesis that a reduction in credit constraint would increase madrasa enrollment by reducing non-madrasa schooling, the costlier option.

Second, madrasa schools have lower returns than the non-madrasa schools (Berman and Stepanyan 2004). Madrasa schools are associated with adverse learning (World Bank 2010) and labor market outcomes (Asadullah 2006, 2009). Again, it is not plausible that, with the credit constraint relaxed, the migrant-sending households will switch away from the option with higher returns and choose madrasa schools. Hence, the credit constraint reduction mechanism does not explain the results that I find.

I also find that the households who are sending migrants to non-Muslim-majority countries—which are also richer countries, in general—are not sending their children to madrasas. If an income effect or a reduction of credit constraints was the mechanism behind the increase in madrasa schooling, then households who are sending members to non-Muslim-majority countries would have also had an increased likelihood of sending their children to madrasas. The insignificant effects of migration to non-Muslim-majority countries further corroborate that the effects of financial remittances are not driving the results.

The second potential mechanism is learning about the potential benefit of madrasa schooling. After a household member has migrated to a Muslim-majority country, migrant-sending households are likely to learn more about these countries and to have more information about what might help a child to migrate in the future. Households might conclude that having a madrasa education could be beneficial for their children to migrate in the future because they learn Arabic or other skills that are useful in Muslim-majority countries. It is also possible that religious schooling could have direct benefits for their children’s future migration prospects; for example, madrasa education could work as a signaling device. Either of these two factors could cause migrant-sending households to send their children to madrasas.

There are two weaknesses in the arguments in favor of this mechanism. First, the number of teachers who can give proper training in spoken Arabic in Bangladeshi madrasas is very low, and the quality of Arabic learning is also very poor (Bhuiyan 2018; Antara 2019). Hence, the Arabic learned in the madrasas in Bangladesh may not be useful for migrating to Muslim-majority countries. Second, there is no evidence that the religion of migrants determines their employability or wage payment in Muslim-majority countries. Indeed, a significant portion of the migrants in the Persian Gulf comes from countries where Islam is not the dominant religion (e.g., India, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka). Migrants from these countries are also high on the list of top remittance senders from the Gulf countries (Naufal 2011; World Bank 2019).

The third mechanism I consider is an increase in religiosity through the transfer of religious preferences. I find suggestive evidence for this mechanism, but I cannot establish a causal relationship between international migration and religiosity. My results show that migration to a Muslim-majority country increases enrollment in madrasas, while there is no evidence of an effect of migrating to a non-Muslim-majority country. As madrasa education is primarily focused on the teaching of Islam, only finding causal impact for migration to Muslim-majority countries suggests that an increase in madrasa enrollment is likely related to the fact that madrasas offer Islamic religious schooling. If a household sends a child to a school where the teaching of a particular faith is the primary focus, this strongly suggests a religious motive for that choice. Consistent with this theory, previous research on Catholic schools in the USA provides evidence that religiosity influences a household’s decision to send a child to a religious school (Sander 2005; Cohen-Zada and Sander 2008). This suggests that an increase in religiosity through the transfer of religious preferences from the destination country is driving the increased madrasa enrollment for children from migrant-sending households.

Since madrasa education appears to be negatively associated with labor market outcomes (Asadullah 2006, 2009; Berman and Stepanyan 2004; World Bank 2010), the increased religiosity mechanism would make economic sense primarily for richer households, who are more likely to be able to afford the loss in income. This in turn implies that the treatment effects should be heterogeneous by household income. I test this implication of the increased religiosity mechanism by estimating treatment effect heterogeneity by income in Table 12. I split the households into two groups based on whether their income is above or below the median. I find that only households with above-median income increases their likelihood of sending a male child to a madrasa in response to having a migrant in a Muslim-majority country.Footnote 35 This finding suggests that the increase in madrasa schooling likely takes place through an increase in religiosity: if the motivation were primarily financial, then poorer households would also choose to send their children to madrasas, especially since they are cheaper than other schools (Al-Samarrai 2007; Asadullah and Chaudhury 2016; Asadullah et al. 2019).Footnote 36

An increase in religiosity through the transfer of religious preferences by an international migrant might lead to other changes in the household to comply with Islamic religious norms. For instance, households might reduce female labor market participation because women in many of the Muslim-majority countries face Islam-imposed cultural restrictions to participate in the labor market (Dildar 2015). Households might also increase the total number of children they have, since Muslims tend to demonstrate opposition to fertility control regardless of the position of Islamic scholars and leaders (McQuillan 2004). I estimate the impact of a household having a migrant abroad on these outcomes in Table 13. The results are consistent with increased religiosity—when the household has a migrant in a Muslim-majority country, female labor market participation decreases and the total number of children in the household increases. Moreover, no significant pattern emerges when the household has a member living in a non-Muslim-majority country. These results further strengthen the suggestive evidence that an increase in household religiosity is a potential underlying mechanism.

The increased religiosity mechanism is consistent with previous research on migration. Migration can cause a person to undergo major transformations of his or her identity. Though several studies document that less religious individuals are more likely to migrate (Myers 2000; Falco and Rotondi 2016), external migrants are likely to become more religious after migrating (Simpson 2003; Williams et al. 2014). Migrants are exposed to the pain of dislocation, and they might revert to their religious identity as a coping mechanism. Muslim migrant laborers from South Asia experience an enhanced sense of religiosity and orthodoxy after their migration (see Kibria 2008). Having migrated to a Muslim-majority country—especially one in the Persian Gulf, where the influence of religion on norms, cultures, and institutions is more overt—a religious Muslim would potentially want to adhere to norms that would reflect the lifestyle of an authentic Muslim. The migrant can then transmit this enhanced sense of religious identity and religiosity to his or her household in the home country. In turn, households would be inclined to imitate norms and behavior that reflect increased adherence to religious practices. Through such practices, they can also gain a higher social status in a society that values religiosity (Kibria 2008). In addition, the increased religiosity of emigrants may dissipate over time when migrating to a non-Muslim-majority country (Aleksynska and Chiswick 2011), which can explain why the migrants do not remit religious preferences from those destinations.

While the evidence presented thus far supports an increase in religiosity as a mechanism for my results, there are two major weaknesses in the arguments in favor of this mechanism. First, choosing religious education is not a direct measure of changes in religiosity; at best, it is a proxy. There are other direct measures that could better capture any change in religiosity, for instance an increase in offering prayers, or an increase in fasting. However, I am not able to measure these because of data limitations—the HIES does not collect data on these religious activities. Therefore, I cannot show impacts on these direct measures, which would provide stronger evidence of the increase in religiosity mechanism. Second, it is very difficult to change religiosity, and it happens gradually over a long period of time. The HIES is a cross-sectional dataset: it does not collect household information over time. Therefore, I can measure only migration that took place in the preceding 5 years of the survey. Similarly, I can construct only a binary measure of school choice (madrasa or non-madrasa), and cannot capture any switching from non-madrasa to madrasa schooling over time. Thus, I am unable to identify the impact of migration on preference for religious schooling over time. As a consequence, I can only claim to show the causal impact of migration on households choosing religious education, and I cannot identify the causal pathway from migration to religiosity to the preference for religious schooling.

6 Conclusion

I have investigated whether international migration affects the preference for religious schools in the home country. I have found that, in Bangladesh, international migration leads to a strong increase in the likelihood of a migrant-sending household sending a male child to a madrasa. With the passage of time, households also start to send their female children to madrasas. I have found that the increase in madrasa education is a result of changing schools for those children who would otherwise attend non-madrasa schools. I have also found that although households switch schools for some of the male children, they do not switch schools for all their children. That is, the likelihood of the household continuing to send at least one child to a non-madrasa school is unchanged.

One key limitation of this paper is that the instrumental variables used are unconventional. However, I have demonstrated that the implications of the potential violations of the exclusion restriction do not compromise the results. Nonetheless, it is possible that there are other channels through which the exclusion restriction is violated that I did not consider. To that end, I tested whether my results would survive if the strict exogeneity restriction is violated, and I found that my results are robust to a minor relaxation of the exclusion restriction assumption. Another major limitation is that I could estimate only the local average treatment effects, as I used an instrumental variable approach. Estimating an average treatment effect is recommended for a possible future research agenda.

This paper’s findings further imply that it is important to pay attention to the learning outcomes of madrasa students so that they can compete in the labor market with their peers from non-madrasa schools. I find that the same household often sends its children to different types of schools. This clearly demonstrates that there is a demand for madrasa schools.

An increase in madrasa education could impact the society both positively and negatively. As madrasa graduates have low learning outcomes and poor labor market outcomes, a systematic increase in madrasa education may lead to adverse human capital production in Bangladesh. Hence, a migration-induced increase in madrasa education could lead to a reduction in the returns to external migration unless these madrasa graduates are differentially compensated. On the other hand, having a madrasa education could help madrasa graduates to migrate abroad to earn more money. Madrasa education can also have other societal impacts through potentially increasing religiosity. The uncertainty of the net impact of increased madrasa education suggests that economists should pay attention to the life- ycle of madrasa graduates of migrant-sending households, as well as to improving the quality of madrasa education so that the learning and labor market outcomes of madrasa graduates can improve. As international migration is very important to developing economies, economists and policy makers need to understand anything that may influence the returns to migration.

Notes

Foreign direct investment inflows are higher than foreign remittance receipts if China is included in the calculation.

See Levitt (1998) for details on the origin of the term “social remittances.”

A detailed description of madrasa education is presented in Section 2.

Roughly eight million Bangladeshis (5% of the total population) live outside of the country (McAuliffe et al. 2019). Although 88% of Bangladeshis are Muslims, 95% of the migrants are followers of Islam (author’s own calculation). Bangladesh is a relatively young country as every three out of five Bangladeshis are 30 years old or younger. Though Bangladeshi households on average have just over four members—thanks to the reduction in fertility rate—two-thirds of Bangladeshis are of working age. While 83% of working-age males participate in the labor market, only 11% of working-age females are in the labor market.

Fruehwirth et al. (2019) used average peer religiosity as an instrument to estimate the causal impact of religiosity on depression.

It is likely that there is a time lag between when an agent experiences an increase in the supply of religious activity and when that agent’s demand adjusts to the increased supply (Hagevi 2017).

Karadja and Prawitz (2019) argue that the contributing mechanism behind emigration causing political changes in Sweden was the availability of an outside option—that is, migrating to the USA.

Conservative norms might also increase in an importing country through international trade (see Autor et al. 2016).

It should be noted that often a transfer from the home country to the host country is assumed to be of negative consequences. Given the dearth of empirical evidence, Clemens and Pritchett (2019) suggest that such assumption is a conjecture.

Bangladesh is similar to Indonesia and Egypt where a parallel Islamic education system has evolved over the years with state patronization (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2016).

While the Arabic language is not a religious subject, it is generally viewed as one in the social context of Bangladesh.