Abstract

This study examines how an increase in home value affects fertility decisions of homeowners in China by exploiting regional heterogeneity in housing markets driven by local regulatory and geographic land constraints. In sharp contrast to the literature on developed countries, our instrumental variable results show a negative fertility response to house value growth driven by the recent housing boom in China, where a 100,000-yuan increase in lagged home values—about 43% of the average housing wealth at baseline—results in a 14% decrease in the likelihood of home-owning women giving birth. Further evidence suggests that underdeveloped credit markets may suppress the positive wealth effect of house value growth on childbearing.

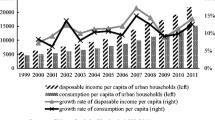

taken from the China Statistical Yearbooks 2010 and 2015. Annual birth rates are calculated using the yearly total number of births to women aged 15–49 divided by the total population of women aged 15–49 in each province, both obtained from the Chinese Population Census 2010 and 2015

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this paper, we use the terms house price, house value, and home value interchangeably when referring to the total market price of a dwelling.

Under this policy, each couple was generally allowed to have only one child, especially in urban areas; couples meeting some eligibility criteria (e.g., ethnic minorities and rural couples whose first child was a girl) could bear two children, or otherwise, they had to pay a fine for above-quota births.

Wang et al. (2017) simulate that the fertility level would not substantially rebound under the two-child policy, implying that the OCP may not be a strictly binding factor when couples make fertility decisions in our study period.

Many emerging economies, such as South Korea, have experienced a housing boom during their rapid-growth transition periods (Chen and Wen 2017), and their fertility effects of home value increases deserve further exploration.

Evidence from developed countries has shown that housing price variations are important for multiple outcomes, including savings, consumption, education, labor supply, marriage, and long-term care insurance demand (e.g., Davidoff 2010; Farnham et al. 2011; Lovenheim 2011; Johnson 2014; Aladangady 2017; Harding and Rosenthal 2017; Zhao and Burge 2017).

All mortgage loans in China are adjustable-rate mortgages with no prepayment penalty.

For example, homeowners can realize their increased housing wealth by selling their homes and moving to a smaller house or a lower-priced real estate market in the future.

The indices include account ownership, making or receiving digital payments, saving at formal financial institutions, borrowers relying on formal credit, the capability of raising emergency funds through savings, among others.

Another potential reason is that housing cost is likely to be a greater portion of the cost of raising a child in developing countries. However, it does not seem plausible for China. Rogoff and Yang (2020) show that housing-related expenditure accounts for 23% of household consumption expenditure in China, which is similar to an average of around 22% in OECD and European Union countries in 2019 (OECD 2021).

The periods of \(t-2\), \(t-1\), and \(t\) then correspond with the waves of 2010, 2012, and 2014, the waves of 2012, 2014, and 2016, or the waves of 2014, 2016, and 2018, respectively. Following the method used by Ding and Lehrer (2010), we examine the potential bias related to panel attrition and find that women who were lost to follow-up are not systematically different from the remaining sample in terms of childbearing decisions.

This means that a woman should have reached age 20, the minimum legal marriage age in China, when first observed in wave \(t-2\). As a robustness check, we use the sample aged 20 to 45 (i.e., aged 16 to 41 in \(t-2\)) and obtain similar results.

Homeownership status is defined by owning a home solely or jointly with working units during the period from \(t-2\) to \(t-1\). The CFPS does not ask respondents directly whether they have moved from \(t-2\) to \(t-1\). We exclude those who moved across communities and within communities (i.e., the property right of the home is newly obtained, or the living spaces are different) between \(t-2\) to \(t-1\). Please refer to Appendix Table 11 for the detailed description of the sample selection.

The sample size for the main regression is larger than the number of women because some women have been observed in four or five waves. The results are robust to limiting the sample to unique observations, that is, including a woman only in her last three observed waves.

A detailed description of the CFPS wealth imputation can be found in Jin and Xie’s (2014) work. As a robustness check, we exclude households with imputed home values and obtain similar results as the main results.

The measure of home equity change is not used here for two reasons. First, whether having a mortgage loan and what the loan amount is may be endogenous. Second, only the CFPS of 2012 provides separate information on mortgages for owner-occupied units and other housing assets, while other waves ask about the total amount of house mortgage loans. In CFPS 2012, about 6.13% had a mortgage loan for the current residence, with an average amount of 78,754 yuan and a median amount of 57,297 yuan.

In China’s real estate market, there have been temporary slowdowns across cities between 2010 and 2014 because of tightening policies and administrative measures (Koss and Shi 2018). Thus, we observe a large proportion of perceived property value loss in the data. We have also decomposed home value changes in Eq. (1) into two variables for increases and decreases in home value. The results, not presented in this article, show little evidence that housing gains and losses have asymmetric effects on fertility in the context of China’s great housing boom.

We restrict the sample to women staying in the same housing unit during the period from \(t-2\) to \(t-1\) so that the change in home value is mostly driven by housing market fluctuations and not by moving residences. In the sensitivity analysis, we will show the robustness of our results to the inclusion of these movers.

The community questionnaire has been administered in CFPS 2010 and 2014.

The fertility policy adjustment and labor market shocks are generally homogeneous within a county in China.

This variable is derived from the Remotely Sensed Data of Land Use in China, collected by the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research from The Chinese Academy of Sciences.

This variable is obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) Regional Economy Database.

We replace the total water area in the instrument with the percentage of water area in each prefectural city. The IV results are remarkably close to the results presented in Table 3, but the instrument becomes weaker in the first stage.

The Anderson–Rubin tests are implemented using the rivtest package in Stata.

Here total housing wealth refers to home equity of all housing units.

There are more than 520 communities in our sample, so it implies a large set of control variables given our limited sample size.

The upper and lower bounds are calculated using the imperfectiv command in Stata (Clarke and Matta 2018).

We also apply a permutation test to examine the exogeneity of our instrument. In the reduced-form regression of fertility on the excluded IV and other covariates, we randomly assign values to water area (or to budgetary revenue per capita). If budgetary revenue per capita (or water area) is correlated with the error term, we may observe a spurious relationship between the permuted IV and fertility. The distributions of t values for the excluded IV from permutating water area or budgetary revenue per capita for 1,500 times show that the p values are both smaller than 0.10 (p = 0.06 and 0.08), implying that the negative effect of the excluded IV on fertility in the reduced-form regression is very likely to be true rather than a biased result from an endogenous IV.

As the CFPS provides no information on household heads, the financial respondent is regarded as the household head. Usually, in Chinese culture, parents buy houses for their adult children, or married couples continue living in the parents’ house. In our data, about 65% of the respondents are household heads or spouses of household heads, 4.6% are daughters of household heads, and 21% are daughters-in-law of household heads.

In this analysis, we exclude those with missing information on community IDs and communities with fewer than eight households.

This is consistent with the literature’s estimates of approximately 90% of homeownership in China (Glaeser et al. 2017).

Dettling and Kearney (2014) also reveal a negative coefficient of Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA)-level house price changes for renters and a positive estimate for homeowners relative to renters. However, contrastingly, they find a net positive effect on births among homeowners, which is indicative of the dominant wealth effects. However, given the net negative effect of community-level median home value changes among homeowners in China, we cannot rule out the possibility that the positive coefficient on \({\Delta HV}_{mct-1}\times {Own}_{imct-1}\) may be driven by the difference in the cost effects between renters and homeowners.

As a robustness check, we also estimate the results using the sample of women with children. The results are qualitatively similar to those reported in Table 6.

We exclude the top 0.5% of the observations with the highest level of household education expenditures. The average education expenditure is 4,911 yuan in the sample of homeowners with only one child.

Greater internet index values imply more advanced credit markets. Details of the index construction are explained in https://en.idf.pku.edu.cn/achievements/seriesofdigitafinanceindexes/490847.htm.

We include interaction terms for every subgroup so that the coefficient on each interaction term shows the estimated effect for the corresponding subgroup.

References

Aksoy CG (2016) Short-Term effects of house prices on birth rates. EBRD Working Paper No. 192, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2846173 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2846173

Aladangady A (2017) Housing wealth and consumption: evidence from geographically linked microdata. American Economic Review 107(11):3415–3446

Alam SA, Pörtner CC (2018) Income shocks, contraceptive use, and timing of fertility. J Dev Econ 131:96–103

Alm J, Lai W, Li X (2021) Housing market regulations and strategic divorce propensity in China. Journal Population Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00853-2

Atalay K, Li A, Whelan S (2021) Housing wealth, fertility intentions and fertility. Journal of Housing Economics, 101787

Becker G (1960) An economic analysis of fertility in demographic and economic change in developed countries. Columbia University Press

Black DA, Kolesnikova N, Sanders SG et al (2013) Are children ‘normal’? Rev Econ Stat 95(1):21–33

Chatterjee S, Vogl T (2018) Escaping Malthus: economic growth and fertility change in the developing world. American Economic Review 108(6):1440–1467

Chen K, Wen Yi (2017) The great housing boom of China. Am Econ J Macroecon 9(2):73–114

Chen T, Kung JK-S (2016) Do land revenue windfalls create a political resource curse? Evidence from China. J Dev Econ 123:86–106

Chen Y, Li F, Qiu Z (2013a) Housing and saving with finance imperfection. Ann Econ Financ 14(1):207–248

Chen Y, Li H, Meng L (2013b) Prenatal sex selection and missing girls in China: evidence from the diffusion of diagnostic ultrasound. Journal of Human Resources 48(1):36–70

Chu CYC, Lin J-C, Tsay W-J (2020) Males’ housing wealth and their marriage market advantage. Journal Population Economics 33:1005–1023

Clark J, Ferrer A (2019) The effect of house prices on fertility: evidence from Canada. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal 13(38):1–32

Clarke D, Matta B (2018) Practical considerations for questionable IVs. Stata Journal 18(3):663–691

Davidoff T (2010) Housing wealth commitment and long-term care insurance demand. J Public Econ 94(1–2):44–49

Daysal MN, Lovenheim M, Siersbæk N et al (2021) Home prices, fertility, and early-life health outcomes. Journal of Public Economics. 198(3):104366

Bono D, Emilia AW, Winter-Ebmer R (2012) Clash of career and family: fertility decisions after job displacement. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(4):659–683

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Klapper L, Singer D et al (2018) The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. World Bank, Washington, DC

Dettling LJ, Kearney MS (2014) House prices and birth rates: the impact of the real estate market on the decision to have a baby. J Public Econ 110:82–100

Ding W, Lehrer SF (2010) Estimating treatment effects from contaminated multi-period education experiments: the dynamic impacts of class size reductions. Rev Econ Stat 92(1):31–42

Ebenstein A (2010) The “missing girls” of China and the unintended consequences of the one child policy. Journal of Human Resources 45(1):87–115

Fang H, Quanlin Gu, Xiong W et al (2016) Demystifying the Chinese housing boom. NBER Macroecon Annu 30(1):105–166

Farnham M, Schmidt L, Sevak P (2011) House prices and marital stability. American Economic Review 101(3):615–619

Finlay K, Magnusson LM (2009) Implementing weak-instrument robust tests for a general class of instrumental-variables models. Stand Genomic Sci 9(3):398–421

Fu S, Liao Yu, Zhang J (2016) The effect of housing wealth on labor force participation: evidence from China. J Hous Econ 33:59–69

Gallego F, Jeanne L (2021) Baby commodity booms? The impact of commodity shocks on fertility decisions and outcomes. Journal Population Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00855-0

Galor O, Weil DN (1996) The gender gap, fertility, and growth. American Economic Review 86(3):374–387

Gao N, Liang P (2019) Home value misestimation and household behavior: evidence from China. China Econ Rev 55:168–180

Glaeser E, Huang W, Ma Y et al (2017) A real estate boom with Chinese characteristics. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1):93–116

Guinnane TW (2011) The historical fertility transition: a guide for economists. Journal Economic Literature 49(3):589–614

Han Li, Kung J-S (2015) Fiscal incentives and policy choices of local governments: evidence from China. J Dev Econ 116:89–104

Harding JP, Rosenthal SS (2017) Homeownership, housing capital gains and self-employment. J Urban Econ 99:120–135

Huttunen K, Kellokumpu J (2016) The effect of job displacement on couples’ fertility decisions. J Law Econ 34(2):403–442

Ito T, Tanaka S (2018) Abolishing user fees, fertility choice, and educational attainment. J Dev Econ 130:33–44

Iwata S, Naoi M (2017) The asymmetric housing wealth effect on childbirth. Rev Econ Household 15:1373–1397

Jin Y, and Yu X (2014) Technical report on household wealth in 2010 and 2012 (in Chinese). Available at www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/docs/20180927132802676920.pdf, accessed February 19, 2019. Technical Report CFPS–29, Institute of Social Science Survey, Peking University

Johnson WR (2014) House prices and female labor force participation. J Urban Econ 82:1–11

Koss R, and Shi X (2018) Stabilizing China’s housing market. IMF Working Paper 18/89. Available at https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2018/wp1889.ashx

Li H, Li J, Yi L et al (2020) Housing wealth and labor supply: evidence from a regression discontinuity design. Journal of Public Economics. 183:104139

Li Lixing, Xiaoyu Wu (2019) Housing price and intergenerational co-residence in urban China. Journal of Housing Economics. 45:101596

Li L, Xiaoyu Wu (2014) Housing prices and entrepreneurship in China. J Comp Econ 42:436–449

Lindo JM (2010) Are children really inferior goods? Evidence from displacement-driven income shocks. Journal of Human Resources 45(2):301–327

Liu AA, Linn J, Qin P et al (2018) Vehicle ownership restrictions and fertility in Beijing. J Dev Econ 135:85–96

Lovenheim MF (2011) The effect of liquid housing wealth on college enrollment. J Law Econ 29:741–771

Lovenheim MF, Mumford KJ (2013) Do family wealth shocks affect fertility choices? Evidence from the housing market. Rev Econ Stat 95(2):464–475

McElroy M, Yang DT (2000) Carrots and sticks: fertility effects of China’s population policies. American Economic Review 90(2):389–392

Mizutani N (2015) The effects of housing wealth on fertility decisions: evidence from Japan. Economics Bulletin 35(4):2710–2724

Nevo A, Rosen AM (2012) Identification with imperfect instruments. Rev Econ Stat 94(3):659–671

OECD (2021) Housing-related expenditure of households. Available at https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC1-1-Housing-related-expenditure-of-households.pdf, accessed September 10, 2021. OECD Affordable Housing Database

Oliveira J (2016) The value of children: inter-generational support, fertility, and human capital. J Dev Econ 120:1–16

Öst CE (2012) Housing and children: simultaneous decisions?—a cohort study of young adults’ housing and family formation decision. J Popul Econ 25(1):349–366

Rogoff KS, and Yang Y (2020) Peak China housing. NBER Working Paper 27697. Available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w27697

Saiz A (2010) The geographic determinants of housing supply. Quart J Econ 125(3):1253–1296

Schaller J (2016) Booms, busts, and fertility: testing the Becker model using gender-specific labor demand. Journal of Human Resources 51(1):1–29

Schultz TP, Zeng Yi (1999) The impact of institutional reform from 1979 through 1987 on fertility in rural China. China Econ Rev 10(2):141–160

Staiger D, Stock JH (1997) Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 65(3):557–586

Sun A, and Zhang Q (2020). Who marries whom in a surging housing market? Journal of Development Economic 146:102492

Wang F, Zhao L, Zhao Z (2017) China’s family planning policies and their labor market consequences. J Popul Econ 30(1):31–68

Wang F (2003) Housing improvement and distribution in urban China: initial evidence from China’s 2000 Census. China Review 3:121–143

Wang X, Wen Yi (2012) Housing prices and the high Chinese saving rate puzzle. China Econ Rev 23:265–283

Wang X, Zhang J (2018) Beyond the quantity-quality tradeoff: population control policy and human capital investment. J Dev Econ 135:222–234

Waxman A, Liang Y, Li S et al (2020) Tightening belts to buy a home: consumption responses to rising housing prices in urban China. Journal of Urban Economics. 115:103190

Wei S-J, Zhang X, Liu Y (2017) Home ownership as status competition: some theory and evidence. J Dev Econ 127:169–186

Whittington LA, Alm J, Elizabeth Peters H (1990) Fertility and the personal exemption: implicit pronatalist policy in the United States. American Economic Review 80(3):545–556

Wrenn DH, Yi J, Zhang Bo (2019) House prices and marriage entry in China. Reg Sci Urban Econ 74:118–130

Xie Yu, Jin Y (2015) Household wealth in China. Chinese Sociological Review 47(3):203–229

Yi J, Zhang J (2010) The effect of house price on fertility: evidence from Hong Kong. Econ Inq 48(3):635–650

Zhang J (2017) The evolution of China’s one-child policy and its effects on family outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31:141–160

Zhao L, Burge G (2017) Housing wealth, property taxes, and labor supply among the elderly. J Law Econ 35(1):227–263

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Wei Huang, Junjian Yi, Fangwen Lu, and seminar participants at the Peking University, Renmin University of China, Fudan University, and Central University of Finance and Economics for helpful comments. The guidance of editor Terra McKinnish and the anonymous referee is greatly appreciated.

Funding

This study was supported by the Key Project of the National Social Science Fund (No. 21ZDA098), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71673313 and No. 71703160), and the “Thematic Research Project on China’s Income Distribution” (No. 21XNLG03) with funding from the research fund of Renmin University of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Terra McKinnish

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Liu, L. & Wang, F. Housing wealth and fertility: evidence from China. J Popul Econ 36, 359–395 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00879-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00879-6