Abstract

We study the short-, medium-, and long-run employment effects of a substantial change in Germany’s parental leave benefit program. In 2007, a means-tested parental leave transfer program that paid benefits for up to 2 years was replaced with an earnings-related transfer that paid benefits for up to 1 year. The reform changed the regulation for prior benefit recipients and added benefits for those who were not eligible before. Although long-run labor force participation did not change substantially—the reform sped up mothers’ labor market return after their benefits expired. Likely pathways for this substantial reform effect are changes in social norms and in mothers’ preferences for economic independence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Parental leave—paid or unpaid—is high on the political agenda in many industrialized countries. Many European countries already have generous parental leave benefits, and other countries are considering introducing or expanding such programs. In this paper, we exploit a major reform of a paid parental leave program to identify the causal effect of paid parental leave on the labor market attachment of recent mothers.

Parental leave regulations differ in the duration of employment-protected parental leave and in the generosity of parental leave benefits in terms of transfer amount, duration, and eligibility. These regulations vary between countries and within countries over time. Even though a growing literature studies the causal relationship between parental leave and maternal labor market outcomes, mothers’ behavioral responses are still not well understood.Footnote 1 Some studies find strengthened labor market attachment in response to more generous or newly introduced parental leave while others conclude the opposite; Rossin-Slater (2018) argues that leave duration may be crucial. A number of authors show that the availability of (paid) parental leave itself can increase employment rates (see Berger and Waldfogel 2004; Burgess et al. 2008; Rossin-Slater et al. 2013; Byker 2014; Byker 2016; Baum and Ruhm 2016; Del Rey et al. 2021). On the other hand, a substantial part of the literature disagrees. Studies of Canada, Australia, Austria, Germany, and Norway report that mothers increase the time spent at home when maternity leave is extended; also, the availability of leave weakens their short-term labor force attachment.Footnote 2

This paper exploits a fundamental reform of the parental leave benefit program in Germany and identifies the program’s causal effect on maternal employment after childbirth. Before the reform, German mothers could claim “child-rearing benefits” conditional on a means test; the benefits typically paid 300 Euro per month for up to 24 months after childbirth. After the reform, benefits are available to all mothers without a means test. The benefits now generally replace 67% of last net earnings, with minimum and maximum amounts fixed at 300 and 1800 Euro per month. These benefits are paid for 12 months (plus 2 months for a partner).

This major revision of Germany’s parental leave policy allows us to identify causal effects that are difficult to identify in scenarios of only minor institutional adjustments. In particular, we study the effects of an introduction of parental leave benefit payments for some mothers (the new benefit recipients) and of a shortening of parental leave benefits for others (the prior benefit recipients); both changes occur simultaneously and in the same economic environment.

Among the few studies looking at the introduction of paid parental leave are Sánchez-Mangas and Sánchez-Marcos (2008) for Spain, Stearns (2018) for the U.K., and Rossin-Slater et al. (2013) for California. A much larger literature covers changes in benefit durations (see e.g., Hanratty and Trzcinski (2009) and Baker and Milligan (2008b) for Canada, Lalive and Zweimüller (2009) and Lalive et al. 2014 for Austria, Dahl et al. (2016) for Norway, Yamaguchi (2019) for Japan, and Mullerova (2017) and Bičáková and Kalíšková (2019) for the Czech Republic). The elements of the German reform render our contribution most similar to Lalive et al. (2014), who study the effects of a shortening and an extension of the duration of cash benefit payments in Austria. In contrast to their study of reforms that occurred consecutively, our reform constitutes a program change that simultaneously reduces the duration of payment for one group and introduces payments for another group. Overall, the German reform is of interest to many countries with similar policies and adds new evidence compared to extant studies of prior reforms by Dustmann and Schönberg (2012) and Schönberg and Ludsteck (2014).

We compare the labor market outcomes for mothers of children born under the old and the new benefit regimes and address the effect of parental leave benefits on maternal employment over the short, medium, and long term. A sensitivity analysis combines the discontinuity approach with a difference-in-differences (DID) framework in order to account for impacts of the business cycle and general trends. There, we compare the adjustment in the reform period for recent mothers with that of mothers of older children who are not directly affected by the reform. We apply duration models to flexibly describe the determinants of the timing of post-birth events.

Several contributions have already investigated the 2007 reform. Kluve and Tamm (2013) and Kluve and Schmitz (2018) found an employment decline in year 1 after childbirth and an increase thereafter using cross-sectional data. Those studies discuss employers’ responses and suggest that the definition of a point of “natural” return to the labor force could be the driving force behind the observed employment patterns. They do not discuss nor investigate the relevance of other channels. In addition, their data is cross sectional and does not provide information on labor earnings of either parent. As we have information on pre-reform gross and net earnings of both spouses, we can characterize more precisely whether couples benefited from the reform. This allows us to more reliably separate prior and new benefit recipients.Footnote 3 In addition, Geyer et al. (2015) estimate a structural labor supply model for mothers and consider outcomes up to 2 years after childbirth.

We go beyond these papers in various ways. First and most importantly, we apply rich survey data to differentiate heterogeneous effects for different groups. Our analyses would not be possible with administrative data, which do not provide information at the household level. Second, our data allow us to assess the mechanisms of how mothers respond to incentives in parental leave programs. Third, prior studies use cross-sectional data which observe mothers only at one point in time and cannot follow the path to labor force participation. In contrast, we apply event study methods to carefully model the employment dynamics after childbirth, which we combine in a sensitivity analysis with a difference-in-differences approach.

We find that the reform yielded strong labor supply responses in the short- and medium run, whereas long-run labor force participation was not affected. During benefit receipt, i.e., in the first year after childbirth, the rate of labor force return declined (insignificantly) for new benefit recipients, whereas prior benefit recipients hardly responded to the reform. At benefit expiration (month 12), prior benefit recipients’ hazards of returning to the labor force increased by a factor of 3 after the reform. Among new benefit recipients, the reform generated a large and significant increase in the rate of labor force return at the time of benefit expiration. The overall time until an average mother with (without) prior benefit receipt returned to the labor force after childbirth declined by 10 (8) months at the median after the reform. We show that likely pathways for this substantial reform effect are changes in social norms and mothers’ preferences for economic independence.

The paper develops as follows. In Section 2, we describe the institutional background and discuss the expected reform effects. Section 3 characterizes the data and our empirical approach. We present the results and robustness tests in Section 4. Section 5 concludes.

2 Institutions and hypotheses

2.1 Institutional background

German parental leave regulations were introduced in the early 1950s and have been modified many times since (see, e.g., Dustmann and Schönberg 2012). The reform of 2007 changed parental leave regulations in a broader effort to adjust the institutional setting to the needs of modern families. The reform affected births after Dec. 31, 2006 and had three main objectives: to financially support all young families, to strengthen mothers’ incentives to return to work after childbirth, and to enhance paternal involvement in child care (Deutscher Bundestag 2006). Even though German fertility was very low (TFR of 1.34 in 2005), this was not an official motivation for the reform.

Three German family policy programs are relevant for our analysis. First, maternity leave (Mutterschutz) and maternity benefits (Mutterschaftsgeld) are available 6 weeks before and up to 8 weeks after childbirth. Mothers are not allowed to work, and their job is protected in that period, i.e., they cannot be laid off. Those employed before maternity leave continue to receive their full net earnings, while those not employed receive no benefits. Second, parents can take parental leave (Elternzeit). Employers must guarantee a parent’s job for up to 3 years after birth. Couples are free to choose which partner uses the leave.

As a third institution, child-rearing benefits (Erziehungsgeld) were government transfers paid to one parent prior to the reform. These benefits were means tested and paid a maximum of 300 Euro per month for up to 24 months (regular benefit version) or, alternatively, 450 Euro per month for 12 months (budget version); however, only a minority of parents (13% in 2006) used the budget version (RWI 2008). The eligibility criteria of the means test relate to the expected family income in years 1 and 2 after childbirth.Footnote 4 In principle, recipients of child-rearing benefits could work part-time; however, as labor earnings counted against the means test, the benefit scheme created strong disincentives for labor force participation. Only “mini-jobs”, i.e., subsidized marginal employment with earnings below 400 Euro per month, did not count against the means test.

The parental leave benefit reform of 2006 changed this third institution leaving maternity leave, maternity benefits, and parental leave unaltered. Parents of children born on or after January 1, 2007 are entitled to “parents’ money” (Elterngeld) instead of child-rearing benefits (Erziehungsgeld). The new benefit generally amounts to two-thirds of average net earnings in the 12 months prior to the birth of the parent who does not work after birth. Parents employed part-time or in marginal employment (mini-job) after childbirth receive 300 Euro per month as a minimum and up to two-thirds of the realized decline in earnings.

A minimum benefit of 300 Euros per month is provided also to those not previously employed. The maximum benefit amounts to 1800 Euro per month. One parent can receive the benefit for up to 12 months, with a second parent eligible for an additional 2 months of benefits. Couples are free to split the available 14 months of benefits between themselves. Single parents can receive the benefit for 14 months.Footnote 5

The new benefit is more generous than the prior means tested benefit in terms of transfer amounts. However, the new benefit is less generous in terms of its payout period of 12–14 months, instead of up to 24 months before.Footnote 6 Before the reform, part-time employment during benefit receipt was considered in the means test. The reform abolished the means test and thus strengthened work incentives.Footnote 7

In this setting, child care is another relevant institution. While child care has been widely available for children aged between 3 and 6, care for children under 3 was lacking in West Germany: in 2006, less than 8% percent of children under 3 attended public child care in West, compared to nearly 50% in East Germany. In response, political agreements of 2005, 2007, and 2008 called for an increase in child care provision to guarantee availability by 2013 (for details see Bauernschuster et al. 2016). Consequently, child care availability for children under 3 increased over time, from coverage rates of 13.6 in 2006 to 27.6% in 2012, with substantial regional variation (BMFSFJ 2015).

2.2 Expected labor supply responses to the reform

We are interested in the effect of the reform on maternal labor force participation. Given the institutional change, behavioral adjustments can differ (i) for the first 12 months after childbirth, i.e., the time of benefit payout, vs. the period afterwards, and (ii) for mothers who would have received child-rearing benefits prior to the reform (prior recipients) vs. those who would not have received pre-reform benefits (new recipients). Next, we discuss the expected responses in the framework of an inter-temporal model of labor supply (see, e.g., Klerman and Leibowitz 1999).

For the first 12 months after childbirth, all prior recipients continue to be eligible. In addition, parents who would have failed the means tests before the reform are newly eligible. Among these new recipients, we expect a drop in labor force participation; if leisure is a normal good labor, supply drops when a transfer is paid. For prior recipients, transfer amounts may now increase beyond 300 Euro per month; this may reduce labor force participation after birth and possibly increase reservation wages. On the other hand, the abolition of the means test renders employment more attractive already in year 1 after birth. Also, the transfer now ends already after 12 instead of 24 months which might generate an incentive to reconnect to the labor market faster: prior recipients may lose a substantial part of their household income after month 12. Overall, we cannot derive a clear hypothesis as to whether the labor market attachment of prior recipients in year 1 after birth goes up or down.

The change in regulations for the period after month 12 differently modifies the labor supply incentives of those who previously could and could not claim child-rearing benefits: prior recipients now lose the benefit already after month 12. Due to a negative income effect, we expect an increase in their labor supply after month 12 compared to the pre-reform situation. In addition, the means tests on household income are abolished thus removing a labor force participation disincentive. New recipients who would not have received a benefit prior to the reform lose their transfer after 12 months. While they should reduce labor supply in the first year after birth after the reform, labor supply models suggest no change in labor market behavior compared to the pre-reform situation after month 12. Thus, at the end of the transfer period, their labor supply should increase to its pre-reform level. Alternatively, the newly available benefit may generate a wealth effect: after the reform, and with the benefit, mothers may be able to afford more time out of work than before the reform and without the benefit. In that case, the reform may as well reduce labor force participation after month 12.

The policy objective of the reform was to strengthen mothers’ incentives to return to work after childbirth. However, from a theoretical perspective, we expect an overall decline in maternal labor force participation during year 1 after birth and an increase for prior recipients after the end of the benefit payout period.

3 Data and empirical approach

3.1 Description of the data

We use data from of the German Socioeconomic Panel (SOEP), a long running panel study which provides detailed household and individual information (Wagner et al. 2007).Footnote 8 Unfortunately, the number of new mothers with births immediately before and after the reform is limited in the SOEP.

The reform affected all births on or after January 1, 2007. It was first discussed in May 2006 and was passed into law in September 2006. This implies that children born in a window of 6 months around January 1, 2007 were conceived before the details of the reform were available. We consider mothers who gave birth in time windows of equal length before and after the reform. While our main analysis uses 24-month periods, i.e., all births observed in 2005/2006 vs. 2007/2008, we offer robustness tests with more narrow windows of observations. We consider all births, independent of prior employment of the mother, and censor spells when another birth occurs.

Our dependent variable describes the number of months until a recent mother returns to the labor market. We consider three outcomes: (a) labor force participation, including full- and part-time work, marginal employment, and registered unemployment, (b) substantial employment, i.e., full- and regular part-time employment, and (c) full-time employment. We regard a transition into a labor market state as absorbing. We study the labor market behavior of mothers for up to 42 months after birth. We use information until December 2011.

We expect heterogeneous responses for prior and new recipients. To test our hypotheses, we have to identify the two groups in the data. In order to determine the potential child-rearing benefit eligibility status of mothers, we use information on the household situation, i.e., partnership, number of children, and gross income in the year before childbirth. We consider households to be ineligible for child-rearing benefits if the gross income of the father before childbirth exceeds the threshold.Footnote 9

We observe 372 women giving birth before and 313 women giving birth after the reform with valid information on month of birth, monthly employment status, and covariates.Footnote 10 For our dependent variables, we observe 149/102/51 exits before, and 111/84/50 exits after the reform, respectively, for the three labor markets states (a–c).

We follow the literature and consider as basic covariates age, region of residence (i.e., East or West), German citizenship, years of education, whether this is a first child, and a single mother. If not indicated otherwise, we treat covariates as time constant, measured at the time of childbirth. However, the treatment effect (see next section) is time-varying with the age of the child. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics. The samples observed before vs. after the reform do not differ greatly. Mothers in the new regime are slightly older and are more likely to have already had a child; this agrees with overall demographic trends. In contrast, we find substantial differences between prior and new benefit recipients with regard to age, education, area of residence, and single-mother status. This confirms the importance of distinguishing the two groups, to allow for potentially heterogeneous reform effects. We also show gross monthly earnings of mothers and their families, as well as the maternal share of household income prior to childbirth. Average monthly earnings before childbirth are around 800 Euro for prior recipients and 1300 Euro for new recipients. As expected, monthly family income is lower for the prior recipients. At the same time, the female share in family income is substantially higher among prior recipients, which points towards the significance of benefits for family income for this particular group.

3.2 Empirical approach

We are interested in mothers’ return to the labor force after childbirth, and the effect of the parental leave benefit reform on the timing of this event. We use semi-parametric Cox hazard models to model the time until labor force transition. This method has three main advantages: (i) it does not impose constraints on the baseline hazard and therefore on duration dependence, (ii) it allows us to account for censored observations, and (iii) it takes advantage of the full distribution of time to exit from the “post-birth out of the labor force state.” We allow for time-varying treatment effects to make the estimates more easily relatable to individual behavior. In addition, we allow for different baseline hazards for treatment and control groups, and for prior and new recipients. This accounts for nonproportionalities in the treatment effect.Footnote 11

We model the hazard of the transition out of the “post-birth out of the labor force” state for females giving birth in the pre- and post-reform periods, 2005/2006 and 2007/2008. As all spells start with a birth, there is no left censoring. We observe women in the out of the labor force state until they either return to the labor force or are right censored. Right censoring occurs if they reach the last survey month (December 2011), or the maximum duration in our sample (42 months), experience another birth, or attrit from the survey sample.Footnote 12

We start out with the log hazard of leaving the “post-birth out of the labor force” state at time t for mother i, conditional on being in this state until time t, λi(t). In our main analysis, we conduct a before-after analysis which evaluates the shift in the baseline hazard after the reform for different parts of the baseline hazard distribution. In addition, we apply a difference-in-differences estimation similar to Fortin et al. (2004), comparing women who are and are not affected by the reform. This accounts for effects such as business cycles and aggregate unemployment trends.

Before-after analyses may evaluate a change in the hazard after a reform using a model such as (1) with a constant effect (α) of the reform on the log hazard; the reform indicator (‘reform’) is coded one for mothers who gave birth after the reform (January 1, 2007), and zero otherwise. Covariates z control for mechanisms affecting the hazard in addition to the reform. They can be time varying and are assumed to shift the log hazard by a factor β.

However, we do not expect a constant treatment effect (α) in our case. Instead, we allow the reform effect to vary over the duration of the spell, which here is identical to the age of the child (‘age’). Model (2) replaces the reform indicator with a vector of its interaction terms with age to evaluate how the baseline hazard changes after the reform:

The before-after analysis provides unbiased estimates of the causal reform effect if three conditions apply. First, there should be no anticipation of the reform, and fertility in the treatment and control groups must be unaffected by the reform. Ideally, one would compare the behavior of mothers where births occurred randomly in the pre- and post-reform periods. Such a situation is approximated if we consider only births from a short window of time around the reform date (January 1, 2007). Due to sample size restrictions, we use a broader time window and test whether results change when the window around the reform date is narrowed.

As a second condition, seasonality should not affect the difference between pre- and post-reform outcomes. We investigate this in a robustness test. This source of bias is less important if the time-window of observations is wider. Finally, we have to assume that there are no specific time-trends in female return to the labor force for those who are affected by the reform. As an approximation, Fig. 1 shows the development of maternal employment since 2001, by the age of the youngest child. While recent years show increasing participation, there is no evidence that such trends were important prior to 2007. In our main specification, a linear time-trend controls for these developments.

In a sensitivity analysis, we apply a difference-in-differences (DID) estimation to account for any general shifts in return to the labor force that occurred after the reform and might bias our results. There are two mechanisms that might bias our before-after comparison: first, the German labor market witnessed a substantial decline in unemployment after 2005; second, there is a discussion of secular shifts in social norms regarding maternal employment which might affect mothers’ labor market return independent of parental leave benefit reforms. It is important to establish that maternal return to the labor force is not just determined by overall shifts in labor demand, or secular cultural shifts. The DID approach can separate both mechanism from the true reform effect. As the treatment group (T), we use women who gave birth shortly before and after the reform date of January 1, 2007. For the control group (C), we consider women who gave birth 3 years earlier, and are therefore not affected by the reform.Footnote 13 Following Fortin et al. (2004), we allow the shift in the post reform hazard, α(t), to consist of one element that describes the causal reform effect, αR(t), and one that describes general changes in the hazard over time, αP(t): α(t) = αP(t) + αR(t). Now, we can describe the models for the treatment and control groups:

Generally, the two elements of the post reform shift, αP(t)j and αR(t)j for j = T, C, are not separately identified. The before-after approach assumes that αP(t)T = 0 and αR(t)C = 0. In the DID framework, we assume that the overall time effects are identical for the two groups, i.e., αP(t) = αP(t)T = αP(t)C.Footnote 14 To keep things simple, we let β = βT = βC. If we set an indicator “treat” to one for treatment and to zero for control observations, we obtain the following model:

Line 1 of Eq. (5) gives the baseline hazard for the two subsamples. In line 2, we consider a possible general shift in the hazard after the reform, which equally affects treatment and control groups (αP(t)). The causal reform effect on the treated is estimated by αR(t)T if there are no heterogeneous uncontrolled time trends for treatment and control groups.

Note that we underestimate the true reform effect. Our sample is too small and has too few multiple spells to credibly account for the distribution of unobserved heterogeneity. The assumption of no unobserved heterogeneity within a hazard rate model with a very flexible baseline hazard tends to bias the estimated hazard ratios towards one (see Ridder 1987, Van den Berg 2001). As such we estimate lower bounds of the true reform effect.

4 Results

4.1 Nonparametric and graphical results

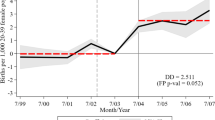

Figure 2 describes the development of maternal labor force participation after birth, before, and after the reform. It shows smoothed hazards and survivor functions.Footnote 15 Before the reform, exit rates of prior recipients (see gray areas in Panels 1 and 2) peaked after 2, 12, 24, and 36 months. These peaks are likely related to the end of maternity leave (8 weeks), the earliest entry age to formal child care (typically 1 year), the end of child-rearing benefits and eased child care access (2 years), and the end of job protection under the parental leave program plus the guaranteed access to child care (3 years). After the reform, exit rates fall in the first few months after birth and increase significantly around month 12, relative to the pre-reform situation. Subsequent exit rates fall and peak again at month 36.

The survivor functions describe the probability of staying out of the labor force after birth. For prior recipients (see Panel 3), this probability increased in year 1 after childbirth; however, at the end of the new benefit payment period, it falls below prior levels for about 1 year. After the child reaches age 2, the survival probability is similar to the pre-reform level.

Panels 2 and 4 show the behavior of new benefit recipients. The pre-reform peaks in exit rates at months 12 and 24 are much smaller than for prior recipients, most likely because there are no expiring child-rearing benefits for this group. The survivor function in Panel 4 shows that after the reform, the probability of staying out of the labor force increases during year 1, then drops well below the pre-reform level in year 2, and subsequently converges towards the pre-reform level. The overall net-effect of the reform on long-term employment appears to be zero, and the impact of the reform thus appears to be intensive rather than extensive.

4.2 Estimation results: before-after comparisons

Next, we apply the semi-parametric before-after model with covariates in order to estimate the effect of the reform. Due to dynamic selection, the non-parametric descriptive hazard rate model cannot be interpreted in a causal way. We use a condensed specification of period-specific hazards. This allows us to estimate the reform effect separately for those who would and would not have been eligible for the pre-reform child-rearing benefits. We allow for different baseline hazards for the two groups. We present our estimation results in terms of hazard ratios and show the hazard ratios for the post-reform effect of exiting non-employment by the age of the child separately for prior and new recipients. The reference group consists of mothers of the given recipient status with a child of the same age in the pre-reform period.

Table 2 presents the estimation results for the three outcomes.Footnote 16 We do not find statistically significant reform effects for the exit rates in the first 11 months for either groupFootnote 17; however, generally exit hazards fall for new benefit recipients after the reform, as expected. The estimations yield mainly significant reform effects around month 12 after birth for both groups.Footnote 18 Mothers who would have been eligible for the pre-reform benefit show an increased exit rate when the new benefit expires. New recipients show mostly significant increases in the exit rates in months 12–14. This increase in exit rates is particularly large for overall labor force participation and substantial employment. For months 15–21, we find increased exit rates to the labor force for both groups after the reform. At later periods, the exit hazards are generally reduced. However, the latter patterns are not precisely estimated.Footnote 19

In order to visualize these reform effects, we simulated the pre- and post-reform survivor functions for prior and new recipients using average characteristics of both groups. Figure 3 describes the predicted survivor functions, separately for prior and new recipients. The reform yields increased exit rates to the labor force starting around month 12 for both groups and for all three outcomes. The survivor rate has dropped by 14 (15) percentage points for prior (new) recipients at month 15 (see Panels 1 and 2). The predicted time for prior recipients to return to the labor force fell at the median by 10 months, from 29 to 19 months after the reform (see Panel 1). This duration fell by 8 months, from 37 to 29 months at the median after the reform for new recipients (see Panel 2). Due to the generally low employment rates of German mothers, we cannot determine the median change for average prior and new benefit recipients: Panels 3–6 show that over the entire period, the survivor curves do not cross the median line. The figures show, however, increased full-time employment probabilities after the reform, particularly for prior benefit recipients starting at month 12.

Simulated suvivor curves for average prior and new recipient. Simulated survivor curves based on estimation results in Table 2

Based on the predicted survivor function, we can sign the cumulative change in the number of hours worked at months 24 or 36. If we assume a constant employment intensity among mothers before and after the reform and apply a “back-of-the-envelope” calculation, the overall number of hours worked increased both for substantial and full-time employment after the reform. This confirms a strengthened labor market attachment.

We can also calculate in a “back-of-the-envelope” fashion the elasticities of the probability of remaining out of the labor force after 6, (12), [24], and {36} months with respect to income lost if not working during the 24 months after birth.Footnote 20 For prior recipients, these elasticities amount to − 0.008, (− 1.429), [− 1.759], and {− 0.765} and for new recipients to − 0.174, (0.679), [1.389], and {1.604}. Prior recipients react as expected; on average, they permanently reduce the probability of staying out of the labor force after a 1% increase in lost income, i.e., they are more likely to return to work. New recipients react differently. They reduce the probability of staying out of the labor force after a reduction in income lost starting with year 1 after child birth.

Overall, we do not observe the expected significant drops in maternal labor force participation during benefit receipt (see Section 2.2), and we find increased labor force participation for all mothers after month 12. The strong increase in the propensity of newly eligible mothers to return to the labor market after month 12 does not agree with the prediction of no behavioral change or even falling labor supply discussed before. In the next section, we explore alternative explanations of this effect by considering specific mechanisms and subgroups.

4.3 Heterogeneity in before-after effects: hypotheses and results

A number of mechanisms may determine the post-reform labor market choices at the point when benefits run out for mothers who newly receive parental leave benefits. In this section, we discuss and evaluate the plausibility of five mechanisms: (i) speed premium, (ii) paternal involvement, (iii) child care availability, (iv) maternal preferences for own income and economic independence, and (v) social norms. We evaluate these mechanisms by comparing the behaviors of those who are and those who are not affected by any given mechanism.Footnote 21

(i) A first rationale for new recipients’ increased labor force attachment after month 12 is that employment after childbirth may now affect future parental leave benefits. This generates a work incentive for mothers who expect to have additional children. To evaluate the plausibility of this explanation, we tested whether mothers of first children respond more strongly to the reform (see Table 3). We do not find significantly higher exit rates after month 12 among first time mothers; thus, there seems to be no support for this mechanism.

(ii) A second mechanism that might explain increased maternal labor force attachment after month 12 may be related to the new regulation for fathers, who can now take two additional months of benefits: as couples often use paternal after maternal leave, the household employment situation changes after month 12. This may facilitate maternal return to work compared to a situation with static household labor supply. To test the plausibility of this mechanism, we evaluated the correlation of maternal exit to the labor force with paternal leave taking by adding interaction terms of indicators of paternal involvement with the reform to the specification (see Table 4). However, we find no evidence to support the hypothesis.

(iii) Next, we investigate whether changes in child care availability over time might be related to maternal labor force attachment.Footnote 22 As a first test, we control for child care coverage for children below age 3 in the maternal county of residence. We can incorporate region-specific and calendar-time varying information for all mothers. The results in Table 5 show small positive effects of child care availability on maternal return to the labor market which is statistically significant only for return to substantial employment. However, our main result, i.e., that new recipients increase their labor supply after 12 months after the reform is even stronger after controlling for child care availability. In additional estimations, we used more flexible specifications and interacted regional child care availability with the age of the child because availability may affect mothers differently depending on the age of her child. The results confirm this expectation (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021) and show significantly positive effects of child care availability on labor force return. However, we continue to find strong and significant reform-induced increases in labor force return after year 1. We also allowed the child age-specific child care availability effects to change after the reform and to differ in urban (high demand) and rural (lower demand) areas. This did not affect our main estimates of the reform effects.Footnote 23

(iv) Another potential mechanism relates to mothers’ preferences with respect to economic independence and an own income (i.e., reference-dependent preferences, see DellaVigna et al. (2017)): before the reform, mothers without child-rearing benefits who left the labor force and cared for a child lost their benefit income at the end of maternity leave, i.e., 8 weeks after birth. After the reform, the loss of an own income typically occurs only after month 12. At that time, mothers may judge the option of returning to work and seeking external care for their child differently than after week 8. Particularly, for mothers who were used to relatively high own earnings prior to birth (see bottom panels of Table 1), the loss of an own income after month 12 can provide an impetus to return to work. This might increase labor force participation rates beyond pre-reform levels. A similar response can result from a consumption habit where behavior responds to a taste for certain consumption levels. Alternatively, it may be influenced by the mothers’ interest in maintaining her economic independence and bargaining position in the partnership.

To test whether the high rate of return to the labor force at month 12 is associated with mothers’ preferences for an own income and economic independence, we apply two measures. First, we test whether women who strongly value being able “to afford something” react stronger to the reform.Footnote 24 These women might be particularly attracted by the new option of maintaining their financial independence. Indeed, we find an (weakly significant) increase in exits to the labor force around month 12 for this particular group (Table 6); a limitation of this result is that due to data restrictions, we have to use information that was gathered after birth and may be endogenous. In addition, we consider information on how couples handle their finances. We assume that women who manage their accounts separately or partly separately value their financial independence either because of a preference for independence or because they do not have access to their spouses’ account (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021).Footnote 25 We find that those mothers who handled their finances independently before the birth generally have a higher hazard of returning to the labor force. Also, they respond stronger to the reform: they are significantly less likely to return to the labor force in months 1–11, and they are substantially (yet mostly insignificantly) more likely to return after the benefit runs out.

Finally, we evaluate mothers’ labor market response by maternal share in household income and by level of education. Both measures also may not only be indicative of preferences regarding economic independence and an own income but also address potential pressure to earn household income. The results (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021) yield that the propensity to return to the labor force is significantly higher for mothers who contribute a large share to household income. Also, these mothers—similar to those with high education—respond to the reform (insignificantly) stronger than others. Overall, the evidence appears to agree with our expectations.

(v) Alternatively, one might argue that the new benefit expiration after month 12 generates a social norm and a signal for young mothers: now it is socially acceptable (or even expected) to return to work and to use child care once the child has reached the age of 1 year (see Olivetti and Petrongolo 2017). Following the model of Akerlof and Kranton (2000), such social norms can influence economic outcomes as they affect a person’s identity that in turn influences the utility function. Similarly, young mothers might respond to (perceived) expectations of their employers (e.g., Bernheim 1994).Footnote 26 Such social norm effects are a common explanation of observed retirement behavior (e.g., Hanel and Riphahn 2012a).Footnote 27 If prior to the reform, the focal, expected, or normal point for young mothers to return to work was after 36 months at the end of employment protection (see Fig. 2); this may have shifted after the reform to month 12, the end of transfer receipt. Thus, increased maternal labor force participation after month 12 could result from a change in social norms.Footnote 28

We use various approaches to test the plausibility of this hypothesis. (a) As a change in social norms takes time, we expect a potential reform effect to increase over time. Thus, we consider an interaction term of the reform effect which indicates whether a child was born in 2008 rather than in 2007. The estimation results in Table 7 show that the increase in exit rates in months 12–14 was significantly higher for births that occurred in 2008 rather than in 2007. In addition, the decline in months 1–11 is (insignificantly) stronger for later births.Footnote 29 While they cannot offer final proof, these results support the social norm hypothesis. (b) Next, we test whether women who value success at work react stronger to the new policy.Footnote 30 Because the traditional social norm of staying at home after childbirth was particularly binding for this group, they might adjust stronger to the change in circumstances than others; following the model of Akerlof and Kranton (2000), for these women, gender identity was particularly binding due to the old social norm. While they do not offer formal proof, the results support this reasoning (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021). (c) Third, personalities respond differently to changes in social norms. One might expect that women with a more external locus of control respond stronger to changes in social norms. We test whether mothers who agree with the statement that “others make the crucial decisions in my life” respond stronger to the reform; we add an interaction term of this characteristic with the reform effect to the empirical specification. The insignificant results agree with this presumption (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021). (d) Finally, we compare the reform response between East- and West-German mothers. Given the socialist heritage of East Germany social norms, there are more in favor of maternal employment and early return to work (see, e.g., Campa and Serafinelli 2019 or Hanel and Riphahn 2012b). If a shift in social norms occurs after the reform, it should be visible particularly in West Germany. The estimation results show that the reform effects around month 12 are economically but not statistically significantly larger in the West (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021). This confirms the plausibility of a shift in social norms after the reform which may drive increased labor force return in months 12–14.Footnote 31

Finally, as we consider a large number of heterogeneity tests to evaluate the plausibility of five separate mechanisms, our results may be subject to the effects of multiple hypotheses testing. In order to test the robustness of our findings, we estimated a model which considers all hypotheses simultaneously, i.e., interactions for a first birth, paternal involvement, year of birth, and valuing economic independence. In addition, the model accounts for child care availability and the relevant main effects. This joint testing reduces the problem of multiple hypotheses testing and estimates partial effects of the different hypotheses. We present the results Appendix Table 11. They confirm that women who value “to be able to afford something” and with a later born child return to the labor market faster around month 12. Overall, we interpret this as suggestive evidence, in support of the hypothesis that the increased labor force participation after month 12 relates to changes in social norms and to a preference for financial independence.

4.4 Robustness tests

4.4.1 Difference-in-differences (DID)

We apply a DID estimation approach to account for potential effects of the business cycle and secular shifts. We reestimated our model using mothers of 3-year-olds as a control group. We allow for different baseline hazards for the treatment and control groups because the form of their exit hazards may differ. Table 8 shows the estimation results when the period effect (αP) is constant across child age groups. In other specifications, we considered time trend controls, used duration-varying effects, and controlled for quarterly calendar effects (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021). Our key results are robust: we find an intensified return to the labor force after year 1 in the post-reform regime for prior and new recipients. Our DID estimates generate a lower bound of the causal effect if the control group similarly responds to an overall shift in social norms. Given that we consider binary measures of labor force participation, potentially heterogeneous business cycle effects on, e.g., the number of hours worked in the treatment and control groups, do not affect our results.

4.4.2 Before-after observation window

So far, we considered maternal employment outcomes for births that occurred 2 years before and after the reform. We also set the time horizon to 6 months before. With this sample, it appears that after the reform prior, benefit recipients returned to employment faster already in months 1–11 rather than around month 12. However, the estimates confirm the large post-reform increase of exit rates into the labor force and substantial employment around month 12 for new recipients (see Table 9).Footnote 32 When setting the observation period to 1 year before and after the reform (see the Bergemann and Riphahn 2021), the reform effect for the new recipients around month 12 is significant for two of the three exit states and even larger than in Table 2. Again, we do not find an increase in the exit rate to substantial employment for prior recipients around month 12.

4.4.3 Omitting December 2006 and January 2007 births

Tamm (2013) showed manipulations of the timing of births around the reform date. In response to this, we reestimated our model in Table 2 after dropping the births of December 2006 and January 2007 (N = 24). This does not affect the results (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021).

4.4.4 Employment before birth

We do not control for the employment status before birth due to its potential endogeneity in our main specification. When controlling for pre-birth employment status in sensitivity analyses, the results remain very stable (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021).Footnote 33

5 Conclusions

This study evaluates the response of maternal labor force participation to a recent reform of the German paid parental leave program. The reform replaced means-tested benefits provided for up to 24 months with earnings-related benefits provided for 12 months, without a means test and thus available for all mothers. The reform affected prior and new benefit recipients, and we expect the groups’ responses to differ. Our rich and detailed survey data allow us to identify these groups. We apply event study methods to evaluate the reform effects in before-after comparisons, which exploit the temporal discontinuity generated by the reform. We provide sensitivity analyses including difference-in-differences procedures.

We expected that after the reform, exit rates from the “post-birth out of the labor force state” decline during benefit receipt (i.e., in months 1–12 after childbirth) for new benefit recipients and possibly increase for prior benefit recipients. We find that the exit rates indeed decline by more for new than for prior benefit recipients; however, these reform effects are insignificant.

We expected that prior benefit recipients who may lose previously available benefits in year 2 after a birth, increase the hazard to exit the “post-birth out of the labor force state” in the period after benefit expiration (i.e., after month 12 after childbirth). We find clear evidence of this effect. Standard labor supply models predict either no reform effect or—if wealth effects are also taken into account—falling labor force participation after benefit expiration for new benefit recipients. The estimates, however, show large and significant increases in the exit rate from the “post-birth out of the labor force state” for new benefit recipients at that point. Thus, both, the prior and new benefit recipients, increase their labor market attachment after the reform when the child reaches age 1. In contrast, long-run maternal labor force participation was not significantly affected by the reform.

At the median, the time until an average mother with (without) prior claims to benefits returns to the labor force after childbirth declined after the reform by 10 (8) months. This represents a substantial reform effect. In addition, the net effect of first declining and then increasing employment in years 1 and 2 after childbirth yields an overall increase in the cumulative number of hours worked by months 24 and 36 on average. At the same time, we do not find significant reform effects in the longer run: as maternal labor force participation at the end of our observation window (i.e., at month 42 after childbirth) did not increase, we conclude that the reform affected only short- and medium-term outcomes.

Our results agree with the findings in the relevant literatures (for a recent survey see Kalb 2018). We find that labor force participation increased for prior benefit recipients, for whom the duration of paid parental leave was reduced. Lalive et al. (2014) study Austrian reforms and find a similar increase in labor force participation when cash benefit duration fell from 24 to 18 months. They find a decline in the propensity to return to the labor force when benefit duration increased from 18 to 30 months. Similarly, Mullerova (2017) investigated Czech mothers’ response to extended benefits and found a decline in the return to the labor force. Schönberg and Ludsteck (2014) study a 1993 German reform, which extended benefit duration from 18 to 24 months and also find a decline in the propensity to return to work.

We find that employment increased for new benefit recipients for whom paid parental leave benefits were newly introduced. This is a common result in the literature on benefit introduction. Hanel (2013) studies the effect of 2–18 weeks of new benefits in Australia and finds that while in the very short-run maternal return to work declines, it increases in months 6–12. Baum and Ruhm (2016) investigate the introduction of paid parental leave in California and find that rights to paid leave are associated with higher work and employment probabilities for mothers 9 to 12 months after birth. Finally, Burgess et al. (2008) show for the UK that mothers with paid maternity rights have a stronger attachment to the labor market that prompts earlier return than on average.

We consider a variety of mechanisms to understand the increase in labor force involvement in year 2 after birth among new benefit recipients. We find patterns that can be explained by preferences for own income and economic independence that derive from reference-dependent preferences. In addition, a shift in social norms might be plausible.

The 2006 reform of paid parental leave pursued three policy objectives: to financially support all young families, to strengthen mothers’ incentives to return to work after childbirth, and to enhance paternal involvement in child care. Our findings yield that the reform met its second objective. The modification of benefits for prior recipients and the introduction of benefits for new recipients increased maternal labor force participation in the short- and medium run. This has far reaching implications in the discussion of paid parental leave effects: offering paid leave to mothers may actually increase their labor market attachment. Our results yield that the reform induced a fast return of mothers to the labor market. This finding of increasing labor force attachment among new beneficiaries of paid parental leave may be of particular interest for countries where universal paid parental leave programs do not yet exist or are available only for a very short period after birth.

Notes

Parents were eligible for full child-rearing benefits if their annual net income was below a threshold. If net income exceeded, the threshold payouts were reduced. The thresholds differed for couples and single parents and varied with the number of children in the household. They also differed for benefits to be paid in months 1–6 vs. 7–24. In addition, the income concept on which eligibility is based differs for months 1–12 and 13–24, resulting in different eligibility rules for months 1–6, 7–12, and 13–24. Benefit eligibility in months 1–12 (13–24) after the birth was based on the income of the father in the calendar year prior to (after) birth and the current income of the mother (see Appendix 1 for more details).

It is possible to double the eligibility duration of the new parental leave benefit if the monthly benefit is cut in half; only about 10% percent of recipients use this option (STBA 2013).

As of 2006, about 77% of families received child-rearing benefits for 1 year and 53% for 2 years (RWI 2007). After the reform, almost 100% of all families received parents’ money (STBA 2008); thus, the share of beneficiaries in year 1 after a birth increased by about 23 percentage points while all prior year 2 recipients lost their benefits. A substantial share of prior recipients of only year 1 benefits may have benefitted from increased amounts: only 25% of fathers and about 50% mothers received the post reform minimum of 300 Euro parents’ money. All others received higher amounts (STBA 2008).

One might be concerned about general equilibrium labor supply effects of the reform. However, overall fertility in Germany is very low and only a small number of families was affected by the reform. Considering the time that equilibrium effects might take to materialize, we do not expect such effects to bias our estimation results.

We use Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), data for years 1984–2012(2016), version 29(33), SOEP, 2012/2016, https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v29 and https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v33.

For details on our eligibility determination please see Appendix 1. Based on our procedure, we predict that about 64% of the mothers in our sample are potentially eligible for the prior child rearing benefit. This is in keeping with actual recipient shares for the births in 2006, where 77% of parents were eligible in months 1–6 and 50% beyond month 6 (Ehlert 2008). We ran sensitivity tests with respect to the determination of the eligibility status. They show that our results are robust to modifications in these procedures.

The sample size declines from 568/472 women originally giving birth before/after the reform. One part of the sample size reduction derives from the ex post coding of many of these births in a subsequently interviewed refreshment sample. In these cases, contemporary employment information is unavailable. In other cases, we lack information on key variables. We do not find significant differences between the considered and omitted observations that raise concern.

Clearly, any continuous time hazard rate model can be approximated by a linear regression. However, least squares estimation will not allow us to identify age-, i.e., duration-specific reform effects. In our setting, the Cox model uses the available information in a particularly efficient way.

We have chosen the upper limit of 42 months in order to include the period of job protection under parental leave (36 months) and the time until a child’s entrance to kindergarten that occurs around age 3. Cygan-Rehm (2016) shows that the reform affected the timing of second births but not the frequency. By month 42, after the first birth, the reform effect just about vanishes. Therefore, our sample restriction should not introduce selection issues.

We considered using unemployed women, whose children are above age 18 as control group. However, the unemployment benefit duration was shortened (for older unemployed) in 2009, which made this approach infeasible. Also, male unemployed of the same age as the mothers could not be used, as men and women were differentially affected by the recession in 2008.

Figure 1 shows the time trends in employment for mothers of recent births and 3-year-olds in panels 1 and 4. In both cases, the time trends are roughly flat, which strengthens the credibility of the parallel trends assumption.

We show figures for the two other labor force participation indicators in Bergemann and Riphahn (2021). The patterns are similar but show lower exit hazards.

Due to small sample size, we group monthly indicators. The estimates for the covariates mainly have the expected signs: those in East Germany and with a first child return to the labor market faster and those without German nationality more slowly. We find no statistically significant time trend. In separate estimations, we found that the results are robust to adding quadratic and cubic time trends (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021). Additional years of age and education increase exit rates, and single mothers show a significantly reduced exit rate to substantial employment.

We also run an extended specification, where the first 11 months are disaggregated into 2 subperiods, 1–6 months and 7–11 months. This did not alter our main results.

We replicated the approach of Kluve and Schmitz (2018) who approximate the groups of new and old recipients based on tertiles of predicted 2006 total household incomes. When we used the bottom household income tertile to capture prior recipients and the top tertile to represent new recipients, estimation results differed from those in Table 2 (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021): the estimated effects for the lower tertile are smaller and less significant than the results in Table 2. In the top tertile, the results in months 12–14 decline in magnitude and in part lose significance whereas the effects for months 15–21 are much larger and significant for all three outcomes. Thus, the choice of data and measurement approach matters.

We tested and rejected the hypothesis that the two groups’ responses to the reform are significantly different.

See Appendix Table 10 for details.

This section describes the results obtained when studying prior and new recipients jointly; the mechanisms should affect both groups, and pooling them provides larger estimation samples. When we repeated the tests for the new recipients only, the resulting patterns are not substantially different from those presented here (available upon request).

For a recent contribution see Österbacka and Räsänen (2021).

In German municipalities, access to child care is rationed. Single parents receive preferential treatment. To test whether this might affect our results, we added child care availability interacted with child age and the triple interaction with single parent status to our model (see the appendix in Bergemann and Riphahn 2021). Our results are robust to adding these controls, as well.

The variable is based on the question “Various things can be important for various people. Are the following things currently very important, important, less important, not at all important for you? Afford to buy something for myself.” We code those who indicate “very important.” The GSOEP included this question in 2004, 2008, and 2012. We use the information that is given closest to childbirth. The findings are robust to omitting results from the 2012 survey.

We thank an anonymous referee for the second interpretation. The variable is based on the question “How do you and your partner decide what to do with the income that one of you or both receive?” The question was asked in 2004 and 2005 (and in 2008) if respondents had a partner. Since we consider financial independence to be an individual predisposition, we use the information that is given well before childbirth and thus can be assumed to be exogenous. Specifically, we allocate the information given in 2004 to the 2005 and 2006 births and the information given in 2005 to the births in 2007 and 2008. We code women with partner who manage their accounts before birth separately or partly separately as financial independent.

Traditionally, West German social norms were opposed to maternal employment and child care use, particularly for small children. For a discussion see, e.g., Borck (2014).

Seibold (2021) uses the concept of “reference points” which determine behavior independent of individually rational decisions.

Such a change in social norms is observationally equivalent to a peer effect that snowballs through the system and can affect heterogeneous individuals in different ways (see Dahl et al. 2014).

Clearly, we are not able distinguish whether the differences in behavior after births in 2007 vs. 2008 truly derive from shifts in social norms or from other factors affecting shifts in choices over time.

The variable uses the question “Various things can be important for various people. Are the following things currently very important, important, less important, not at all important for you? Be successful in once career.” We code those who indicate “very important” and “important.” The GSOEP included this question in 2004 and 2008. We use the information that is given closest before birth.

In an additional test, we find that those living in the countryside respond significantly more strongly to the end of the benefit payout than those in urban areas (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2021). This agrees with the expectations that a change in norms matters more for the rural population.

To avoid multicollinearity with the baseline hazard we did not use a time trend here.

In a preliminary discussion paper (see Bergemann and Riphahn 2020), we additionally describe robustness tests with respect to potential seasonality, the definition of child-rearing benefit eligibility, potential misreporting of labor force participation, and seam effects.

References

Akerlof G, Kranton R (2000) Economics and identity. Quart J Econ 115:715–753

Baker M, Milligan K (2008a) How does job-protected maternity leave affect mothers’ employment? J Law Econ 26(4):655–691

Baker M, Milligan K (2008b) Maternal employment, breastfeeding, and health: evidence from maternity leave mandates. J Health Econ 27(4):871–887

Bauernschuster S, Hener T, Rainer H (2016) Children of a (Policy) revolution: the introduction of universal child care and its effect on fertility. J Eur Econ Assoc 14(4):975–1005

Baum CL, Ruhm CJ (2016) The effects of paid family leave in California on labor market outcomes. J Policy Anal Manage 35(2):333–356

Bergemann A, Riphahn RT (2020) Maternal employment effects of paid parental leave, IFAU Working Paper No.2020:6, Uppsala

Bergemann A, Riphahn RT (2021) Maternal employment effects of paid parental leave, SOM Research Report, 2021016-EEF, Groningen

Berger LM, Waldfogel J (2004) Maternity leave and the employment of new mothers in the United States. J Popul Econ 17(2):331–349

Bernheim D (1994) A theory of conformity. J Polit Econ 103(5):841–877

Bičáková A, Kalíšková K (2019) (Un)intended effects of parental leave policies: evidence from the Czech Republic. Labour Econ 61.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.07.003

BMFSFJ (2015) Kinderbetreuung, see http://www.bmfsfj.de/BMFSFJ/Kinder-und-Jugend/kinderbetreuung.html. Last access 16.05.2015

Borck R (2014) Adieu Rabenmutter – The effect of culture on fertility, female labour supply, the gender wage gap and childcare. J Popul Econ 27(3):739–765

Burgess S, Gregg P, Propper C, Washbrook E (2008) Maternity rights and mothers’ return to work. Labour Econ 15(2):168–201

Byker TS (2014) Fertility and women’s economic outcomes in the United States, Peru and South Africa, Dissertation, University of Michigan

Byker TS (2016) Paid parental leave laws in the United States: does short-duration leave affect women’s labor-force attachment? Am Econ Rev: Pap Proc 106(5):242–246

Campa P, Serafinelli M (2019) Politico-economic regimes and attitudes: female workers under state socialism. Rev Econ Stat 101(2):233–248

Cygan-Rehm K (2016) Parental leave benefit and differential fertility responses: evidence from a German reform. J Popul Econ 29(1):73–103

Dahl GB, Løken KV, Mogstad M, Salvanes KV (2016) What is the case for paid maternity leave? Rev Econ Stat 98(4):655–670

Dahl GB, Løken KV, Mogstad M (2014) Peer effects in program participation. Am Econ Rev 104(7):2049–2074

Rey D, Elena AK, Silva JI (2021) Maternity leave and female labor force participation: evidence from 159 countries. J Popul Econ 34:803–824

DellaVigna S, Lindner A, Reizer B, Schmieder JF (2017) Reference-dependent job search: evidence from Hungary. Quart J Econ 132(4):1969–2018

Deutscher Bundestag (2006) Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD. Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Einführung des Elterngeldes, Drucksache 16/1889, 20.06.2006

Dustmann C, Schönberg U (2012) Expansions in maternity leave coverage and children’s long-term outcomes. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(3):190–224

Ehlert N (2008) Dossier: Elterngeld als Teil nachhaltiger Familienpolitik. BMFSFJ, Berlin

Fortin B, Lacroix G, Drolet S (2004) Welfare benefits and the duration of welfare spells: evidence from a natural experiment in Canada. J Public Econ 88(7–8):1495–1520

Geyer J, Haan P, Wrohlich K (2015) The effects of family policy on maternal labor supply: combining evidence from a structural model and a quasi-experimental approach. Labour Econ 36:84–98

Hanel B (2013) The impact of paid maternity leave rights on labour market outcomes. Economic Record 89:339–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12057

Hanel B, Riphahn RT (2012a) The timing of retirement—new evidence from Swiss female workers. Labour Econ 19(5):718–728

Hanel B, Riphahn RT (2012b) The employment of mothers-recent developments and their determinants in East and West Germany. J Econ Stat (jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie Und Statistik) 232(2):146–176

Hanratty M, Trzcinski E (2009) Who benefits from paid family leave: impact of expansions in Canadian paid family leave on maternal employment and transfer income. J Popul Econ 22(3):693–711

Kalb G (2018) Paid parental leave and female labour supply: a review. Economic Record 94(304):80–100

Klerman JA, Leibowitz A (1999) Job continuity among new mothers. Demography 36(2):145–155

Kluve J, Schmitz S (2018) Back to work: parental benefits and mothers’ labor market outcomes in the medium-run. Ind Labor Relat Rev 71(1):143–173

Kluve J, Tamm M (2013) Parental leave regulations, mothers’ labor force attachment and fathers’ childcare involvement: evidence from a natural experiment. J Popul Econ 26(3):983–1005

Lalive R, Schlosser A, Steinhauer A, Zweimüller J (2014) Parental leave and mothers’ careers: the relative importance of job protection and cash benefits. Rev Econ Stud 81(1):219–265

Lalive R, Zweimüller J (2009) How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. Q J Econ 124(3):1363–1402

Mullerova A (2017) Family policy and maternal employment in the Czech transition: a natural experiment. J Popul Econ 30(4):1185–1210

Nandi A, Jahagirdar D, Dimitris MC, Labrecque JA, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS, Vincent I, Atabay E, Harper S, Earle A, Heymann SJ (2018) The impact of parental and medical leave policies on socioeconomic and health outcomes in OECD countries: a systematic review of the empirical literature. Milbank Q 96:434–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12340

Olivetti C, Petrongolo B (2017) The economic consequences of family policies: lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1):205–230

Österbacka E, Räsänen T (2021) Back to work or stay at home? Family policies and maternal employment in Finland. J Popul Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00843-4

Ridder G (1987) The sensitivity of duration models to misspecified unobserved heterogeneity and duration dependence, Working paper, Groningen University

Rossin-Slater M (2018) Maternity and family leave policy. In: Hoffman Saul D, Averett Susan L, Argys Laura M (eds) The Oxford handbook of women and the economy. Oxford University Press, pp 323–342

Rossin-Slater M, Ruhm CJ, Waldfogel J (2013) The effects of California’s paid family leave program on mothers’ leave-taking and subsequent labor market outcomes. J Policy Anal Manage 32(2):224–245

RWI (Rheinisch-Westfälisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung) (2007) Zwischenbericht zur Evaluation des Gesetzes zum Elterngeld und zur Elternzeit. Zwischenbericht 2007, Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, Berlin

RWI (Rheinisch-Westfälisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung) (2008) Evaluation des Gesetzes zum Elterngeld und zur Elternzeit. Endbericht 2008, RWI-Projektbericht, mimeo, Essen

Sánchez-Mangas R, Sánchez-Marcos V (2008) Balancing family and work: the effect of cash benefits for working mothers. Labour Econ 15(6):1127–1142

Schönberg U, Ludsteck J (2014) Expansions in maternity leave coverage and mothers’ labor market outcomes after childbirth. J Law Econ 32(3):469–506

Seibold A (2021) Reference points for retirement behavior: evidence from German pension discontinuities. Am Econ Rev, forthcoming

STBA (Statistisches Bundesamt) (2008) Elterngeld für Geburten 2007 nach Kreisen, Wiesbaden

STBA (Statistisches Bundesamt) (2013) Öffentliche Sozialleistungen. Statistik zum Elterngeld - Beendete Leistungsbezüge für im Jahr 2011 geborene Kinder, Wiesbaden

Stearns J (2018) The long-run effects of wage replacement and job protection: evidence from two maternity leave reforms in Great Britain, mimeo. Available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3030808

Tamm M (2013) The impact of a large parental leave benefit reform on the timing of birth around the day of implementation. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 75(4):585–601

Van den Berg GJ (2001) Duration models: specification, identification, and multiple durations. In: Heckman JJ, Leamer E (eds) Handbook of econometrics, vol V. Elsevier, North Holland Amsterdam

Wagner GG, Frick J, Schupp J (2007) The German socio-economic panel study (SOEP): scope, evolution, and enhancements. J Appl Soc Sci Stud (schmollers Jahrbuch) 127(1):139–170

Yamaguchi Shintar (2019) Effects of parental leave policies on female career and fertility choices. Quant Econ 10(3):1195–1232

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. We acknowledge the advice of three anonymous referees and editor Shuaizhang Feng in addition to numerous individuals and seminar participants whom we list fully in our discussion paper (Bergemann and Riphahn 2021).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Shuaizhang Feng

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Child-rearing benefits: institutional detail and calculations

1.1 Institutional detail

Child-rearing benefits (Erziehungsgeld) were paid to one parent prior to the reform. These benefits were means tested and paid a maximum of 300 Euro per month for up to 24 months (regular benefit version) or, alternatively, 450 Euro per month for 12 months (budget version); however, only a minority of parents (13% in 2006) used the budget version (RWI 2008). The eligibility criteria of the means test relate to the expected family income in years 1 and 2 after childbirth. In principle, recipients of child-rearing benefits could work part-time; however, as labor earnings counted against the means test, the benefit scheme created strong disincentives for labor force participation. Only “mini-jobs,” i.e., subsidized marginal employment with earnings below 400 Euro per month, did not count against the means test. Parents were eligible for full child-rearing benefits if their annual net income was below a threshold. If net income exceeded, the threshold payouts were reduced. The thresholds differed for couples and single parents and varied with the number of children in the household. They also differed for benefits to be paid in months 1–6 vs. 7–24. In addition, the income concept on which eligibility is based differs for months 1–12 and 13–24, resulting in different eligibility rules for months 1–6, 7–12, and 13–24. Benefit eligibility in months 1–12 (13–24) after the birth was based on the income of the father in the calendar year prior to (after) birth and the current income of the mother.

For the regular benefit, the following rules governed payout (different thresholds for the budget version): married or cohabiting couples were eligible for child-rearing benefits during the first 6 months after birth if their annual net income in the calendar year prior to the birth was below 30,000 Euro. For single-parent families, this threshold amounted to 23,000 Euro. If there were additional children in the household, the annual eligibility thresholds increased by 3140 Euro per child. After month 6, the thresholds dropped to 16,500 Euro and 13,500 for couples and single parents, respectively. If net income exceeded this amount, payouts were reduced. Benefit reductions amounted to 5.2% of the net income amount beyond the threshold.

The calculation of benefit eligibility for months 13–24 was based on the annual net income as of the calendar year of the birth. Annual net income was calculated by reducing gross income by 24% (19% for civil servants) and by subtracting a deductible of 922 Euro. No benefits were paid after month 7 if net annual incomes exceeded 22,086 and 19,086 Euro for couples and single parents, respectively. The gross annual income thresholds for the full and zero benefit amounts amount to roughly (16,500 + 922)/.76 = 22,924 and (22,086 + 922)/.76 = 30,273 Euro for couples and to (13,500 + 922)/.76 = 18,976 and (19,086 + 922)/.76 = 26,326 Euro for singles. For children born in 2006, 23% of parents received no benefit, about one quarter received a reduced benefit, and half received the maximum benefit for more than 6 months (Ehlert 2008).

1.2 Our approximation

The eligibility rules differ for months 1–6, 7–12, and 13–24 after birth. In our analysis, we use the rules for months 7–12 to determine eligibility. In months 7–12 after childbirth, the income of the father over the 12 months before childbirth and the current income of the mother count towards the means test. As maternal post-birth employment may respond to the reform, we prefer to rely on paternal pre-birth income. If this paternal income exceeds the means test threshold already, the household will not be eligible. In all other cases, we consider the households to be at least potentially eligible. Based on this procedure, we predict that about 64% of the mothers in our sample are potentially eligible for the prior child-rearing benefit. This is in keeping with actual recipient shares for the births in 2006, where 77% of parents were eligible in months 1–6 and 50% beyond month 6 (Ehlert 2008).

1.3 Robustness test

We investigate the robustness of our results to our approach of defining the pre-reform benefit eligibility status. First, we conduct a sensitivity analysis with respect to the eligibility rules for child-rearing benefit. So far, we used the rules to determine benefit eligibility in months 7–12. When we instead consider the requirements for benefit eligibility in months 13–24 and replicate our analyses, the baseline specification confirms the significant increase in the hazard rate around month 12 for prior and new recipients. Second, given our rich household-level information, we can group mothers who would have received pre-reform child-rearing benefits more finely into those (i) who certainly would have received the full amount of 300 Euro, (ii) those who certainly would have received a partial amount, and (iii) those who would have received the full or a partial amount if they reduced their working hours after birth. We estimate the reform effects separately for these groups. We find that mothers who certainly would have received the full amount increased their exit rates to the labor force already in year 1 after birth, whereas those who would have received only a partial amount or for whom this is not certain react mainly around month 12.

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergemann, A., Riphahn, R.T. Maternal employment effects of paid parental leave. J Popul Econ 36, 139–178 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00878-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00878-7