Abstract

National Artificial Intelligence (AI) strategies articulate imaginaries of the integration of AI into society and envision the governing of AI research, development and applications accordingly. To integrate these central aspects of national AI strategies under one coherent perspective, this paper presented an analysis of Germany’s strategy ‘AI made in Germany’ through the conceptual lens of ordoliberal political rationality. The first part of the paper analyses how the guiding vision of a human-centric AI not only adheres to ethical and legal principles consistent with Germany’s liberal democratic constitutional system but also addresses the risks and promises inherent to the ordoliberal problematization of freedom. Second, it is scrutinized how the strategy cultivates the fear of not achieving technological sovereignty in the AI sector. Thereby, it frames the global AI race as a race of competing (national) approaches to governing AI and articulates an ordoliberal approach to governing AI (the ‘third way’), according to which government has to operate between the twin dangers of governing too much and not governing enough. Third, the paper analyses how this ordoliberal proportionality of governing structures Germany’s Science Technology & Innovation Policy. It is shown that the corresponding risk-based approach of regulating AI constitutes a security apparatus as it produces an assessment of fears: weighting the fear of the failure to innovate with the fear of the ramifications of innovation. Finally, two lines of critical engagement based on this analysis are conducted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Innovations in the Artificial Intelligence (AI) subfield of Machine Learning that is already used in many real-life applications such as virtual assistants, autonomous vehicles and facial recognition software have made AI a matter of concern for policymaking. In the past 10 years or so, many governments and supranational organizations have presented their visions of the development, application and regulation of AI. Among these various actors, there is a consensus that the technological change driven by AI is already taking place and, thus, can neither be stopped nor ignored. Therefore, it would be important to actively shape these developments to leverage the benefits of AI and control its risks. Supranational organizations and non-governmental organizations have created ethical guidelines for regulating AI according to ‘universally applicable’ norms and principles (Hagendorff 2020). Nations’ states articulate the opportunity (and urgency) to determine rules and measures to push ahead or restrict the integration of AI in accordance with national interests and public goods such as wealth, security, health and sustainability. Moreover, they portray themselves as participants in a global AI race, competing over economic and geopolitical power (Savage 2020).

Most of the AI governance research has approached these policies by conducting (comparative) policy assessments, evaluating from a political, ethical or legal perspective or based on criteria of competitiveness, and providing policy recommendations accordingly (Carriço, 2018; Cath et al. 2018; Chatterjee 2020; Ebers et al. 2021; Floridi 2021; Foffano et al. 2023; Hine and Floridi 2022; Ossewaarde and Gulenc 2020; Paltieli 2022; Radu 2021; Roberts et al. 2021a, b; Smuha et al. 2021; Veale and Zuiderveen Borgesius 2021). Some scholars have not so much focused on the regulatory aspects of these national strategies but on the imaginaries they articulate. These imaginaries connect technological expectations regarding AI futures with national histories, identities, myths, (philosophical) traditions, and pathways (Bareis and Katzenbach 2021; Biju and Gayathri 2023; Hine and Floridi 2022; Köstler and Ossewaarde 2022; Ossewaarde and Gulenc 2020). Ossewaarde and Gulenc (2020) have pointed out the mythical nature that these policies ascribe to AI and the technological solutionism and imperialist ambitions inherent in them. Moreover, as the authors stress, “AI strategy papers play a central role in perpetuating existing power structures both quantitatively, by hindering other voices, and qualitatively by ‘normalizing’ certain political choices.” (2020, 54).

What all these studies on AI strategies lack, however, is a conceptual framework that enables us to integrate the imagination and the governing of AI under one coherent analytical perspective and to understand the precise form of political power that is exercised and reproduced in national AI strategies.

To fill this research gap, this paper presents an analysis of Germany’s national AI strategy, launched in 2018 under the title ‘AI made in Germany’ (AImiG), through the conceptual lens of governmentality, as it has been developed by Michel Foucault and the many scholars building on his works. The concept captures a historical shift in the way power is imagined, rationalized, and exercised in modern societies (Walters and Tazzioli 2023, 1). It has been used to analyze the problematization and governance of various socio-political issues as well as the anticipation of uncertain futures and the ways these are acted on (Anderson 2010, 780). Applied to our subject, the concept enables us to account for the governmental rationalities that structure both the imagination of AI futures and the corresponding governing of AI research, innovations and applications. This way, political power is understood as a productive force: it is not s.th. that is simply exercised upon AI, with the latter existing independent of the former. Instead, power shapes the very forms of AI, both imagined and materialized.

The case of Germany’s AI strategy is particularly instructive because it does not only articulate a national framing of the future of AI and defines measures to achieve it. It also claims to open a ‘third way’ between an unrestrained, bottom-up market-driven approach to AI innovations and a rigid top-down state-driven approach to regulating AI. It presents this ‘third way’ as an alternative to an AI-powered surveillance capitalism and an AI-powered surveillance state. It reframes the global race to AI as a race of competing models of both governing AI and governing with AI. Envisioning this ‘third way’ can hence be understood as performing a national identity through problematizing certain other forms of engaging with AI: while AI in the wrong hands would pose a threat to the freedom of consumers and citizens, an “AI made in Germany” could actually benefit them. The case of Germany, hence, calls for an analysis that investigates national strategies not only as a particular imaginary of the future integration of AI in society but also as a re-imagination of responsible statecraft as facilitator of this promising sociotechnical future. As I will argue, the particular rationality of government that is enacted in Germany’s AI strategy can best be understood as ordoliberalism, a political economy that assigns the state the task of maintaining the market economy and eliminating economic disruptions through “market-compliant” interventions. It heavily influenced the creation of the social market economy in post-WW2 West Germany and remains a central source of inspiration to the Christian Democratic Party, under whose government responsibility the AI strategy was developed.

In the following paragraph, I will briefly introduce the governmentality concept with a particular focus on ordoliberalism and the role of technology.

2 Concept: governmentality

To analyze Germany’s national AI strategy, I propose to draw on the concept of governmentality. In his lectures on the history of governmentality (Foucault 2007, 2008), Michel Foucault developed a notion of government that encompasses the ‘totality of institutions and practices by means of which people are directed, from administration to education’ (2007, 16). Governing can be accomplished by a variety of ‘governmental technologies’ (Foucault 2008, 297): expertise, calculations, devices, architectures, institutions, laws, sets of formal and informal rules etc. The concept, therefore, does not refer exclusively to the actions of a state but addresses any more or less calculated and strategic activity of a multiplicity of actors aiming to act at the actions of others. However, since the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, power relations have been intertwined within the state and the state has become the convergence point for coordinating the different forms of the ‘conduct of conduct’.

‘Governmentality’ is Foucault’s term for a specific rationality of governing that can be traced back to the Christian pastorate, but only became the determining principle of government in liberalism. It breaks with a metaphysically legitimized understanding of social order and a rationality of governing that is solely fixed on the maintenance and expansion of the power of the sovereign. Liberal governmentality, henceforth, is concerned with the well-being, prosperity and happiness of the population and every individual. Inhabitants of a territory are no longer treated as subjects who have to submit to the will of the sovereign and the divine order. Instead, they are viewed as both individuals (that is: white male adults) endowed with natural rights and liberties that are to be respected and protected and as a population determined by biologic processes that have to be nurtured or confined. From the perspective of political economy, the market appears as a place where individuals take advantage of their liberties in the form of pursuing self-interests and making rational choices accordingly. The free interplay of these interests and choices would lead to a dynamic process of supply and demand, resulting in the best possible satisfaction of needs as well as economic growth and social progress. The market, thus, is to be seen as the ideal mechanism to realize the common good—understood as the material well-being of the population and the wealth of the nation. Consequently, government has to respect the natural laws of biologic life and the quasi-natural laws of the market because their ignorance, misunderstanding or disregard leads to negative consequences. Liberal governmentality, therefore, does not align reality with a political norm, but makes reality the norm: It neither wants to force actions nor create causal effects in reality but aims to ensure the working of natural/economic modes of regulation and ordering.

However, liberal government cannot be reduced to this moment of enabling individual freedom and the free play of market forces. The well-being of individuals and the population appears in need of protection as their life and property, the economic processes and the liberal state itself are endangered by certain individuals or sub-populations that demonstrate a lack of rationality, prudentialism and responsibility. Therefore, the guiding principle of liberalism to acknowledge and praise individual freedom corresponds to a governing of the way freedom is exercised. Security becomes the necessary downside of freedom as security measures are employed to produce appropriate forms of self-conduct.

However, these necessary regulations must not interfere with the laws of the market. The liberal problematization of freedom follows the model of an economic calculation: it offsets the benefits with the costs of freedom. Consequently, it seeks to maximize the positive elements of economic circulation while minimizing what is risky and inconvenient. In this modality of risk management, which Foucault describes as ‘apparatuses of security’ (2007, 21), ‘irrational’, ‘dangerous’ or ‘deviant’ behaviour is viewed as unproblematic as long as it stays in an appropriate range. Liberalism, thus, poses the question of how to keep the risks of freedom ‘within limits that are socially and economically acceptable and revolve around a mean that one will see as, say, optimal for a given social functioning’ (ibid., 5).

Ordoliberalism was developed in the 1930s by a number of German political economists in opposition to the laissez-faire liberalism of the nineteenth century and the emerging totalitarianisms of Communism and National Socialism (Sally 1996; Berghahn and Young 2013). The approach—referred to by ordoliberalism as the “Third Way”—was a response to the prevailing belief in a self-regulating market and its devastating social consequences of the 1930s. Instead of interpreting the market both as a natural economic reality with its own laws and as a corrective and outer limit of the state, ordoliberals argue that the market requires a regulatory framework that makes orderly economic interaction possible in the first place. Without rules for economic processes, uncontrolled and spontaneous monopolies and oligopolies would develop, distorting the market and thus undermine the formal legal guarantees of economic freedoms (Sally 1996, 237). As Foucault has stressed in his analysis of ordoliberalism, ‘competition as an essential economic logic will only appear and produce its effects under certain conditions which have to be carefully and artificially constructed. This means that pure competition is not a primitive given. It can only be the result of lengthy efforts’ (Foucault 2008, 120). Moreover, ordoliberal thinkers saw a destruction of individuality as a result of the interplay of expanding state power and state sponsored mass consumption—regardless of welfare state, communist or Nazi policies. In the context of the construction of the social market economy in post-war Germany, this critique was connected to the critique of the alleged manipulation of consumers through psycho-social advertising techniques which had been a widespread belief among the German public since the late 1950s. For the ordoliberals, the sovereign consumer hence appeared as a subject that had to be produced through appropriate governmental activity in the first place. From this perspective, laissez-faire can never suffice to enable the sovereignty of consumers to achieve the central position within the market mechanism that has been attributed to them since Adam Smith—a position which they should also take in the social market economy. Rather, the state has an active role to play.

Through economic policy including consumer protection and education, ordoliberalism aims to ensure that such market failures are remedied or do not occur in the first place. However, while economic policy should define the regulatory framework for economic players, it should not intervene in day-to-day economic activity on the market by means of state interventionism. State intervention should itself be in line with the market. In other words, what freedom requires is not an interventionist state that intervenes directly in the economy, but “a strong state—a state above the economy, above the interests—there where it belongs in the interests of a liberal economic policy” (Sally 1996, 247). The “social” element of Germany’s social market economy, therefore, does not refer to state ownership, state panning or interventionism. Instead, it refers to the idea of a rules-based economy in which social interests are properly accounted for.

The governmentality concept has been used by many scholars to account for government in a variety of settings such as the factory, the school, the organization, and the public sphere where practices, knowledge, and power become interconnected to enact particular forms of conduct and self-conduct. Specific attention has been paid to ‘advanced’ or ‘neo-liberal’ government and the technologies of government that aim to establish entrepreneurial subjectivities and economic rationality across society. By focusing on calculative practices such as accounting (Miller 2008) and psychometric testing (Rose 1998) technologies of neo-liberal government have been predominantly addressed as techniques and far less as material devices. However, the situation has considerably changed in the last few years. Meanwhile, numerous studies are focusing on the governmentality of digital devices and algorithms. Digital technologies would enable precisely those practices of ‘governance of the self’ (Introna 2016) and ‘governing at distance’ (see for example Tironi and Valderrama 2021; Drake 2011; Borch 2017) that are topical for neo-liberal government. Moreover, the advent of these technologies has been analyzed as a new rationality of governing, frequently coined as ‘algorithmic governmentality’ (Roberts and Elbe 2017; Rouvroy and Berns 2013) or ‘algorithmic reason’ (Aradau and Blanke 2022).

While these studies have focused on the strategic use of technology for the purpose of governing, they do not reflect on the technological preoccupation of modern government as such. As Barry (2001) has stressed, technology is not only a mode of enacting government but also the object of governmental interventions. Accordingly, Barry introduces the notion of a ‘technological society’ to refer to a ‘political preoccupation with the problems technology poses, with the potential benefits it promises, and with the models of social and political order it seems to make available.’ (ibid., 2) This reflection opens up a shift within the study of governmentality from the problematization of subjectivities and corresponding technologies of government to the problematization and government of technologies. With regard to the relationship between government and algorithmic technologies, the focus of governmentality can be extended from analyzing the algorithmic prediction of future events and corresponding forms of algorithmic conduct of conduct to analyzing the imagination of algorithmic futures and the corresponding governing of algorithmic practices.

Applying this broadened perspective to Germany’s AI strategy, the remainder of the paper will analyze how the imagination of an AI made in Germany and the corresponding (envisioned) governing of AI enacts—and is enacted by—an ordoliberal governmentality.

3 Data and methods

This analysis is based on an in-depth reading of publicly available documents.Footnote 1 These include: strategy papers, reports, answers to parliamentary questions, press releases, and other official statements from the Federal Government, Federal Ministries, the state authorities involved in the development and implementation of the strategy including the Central Office for Information Technology in the Security Sector, the Federal Criminal Police Office, the Federal Office for Information Security, the Cybersecurity Innovation Agency, and reports from the working groups of Learning Systems—Germany’s Platform for AI (LS), the German government’s Data Ethics Commission (DEC), and the German parliament’s Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence (SCAI). as well as statements and policy papers from institutions involved in the development and implementation of the national strategy including the German Institute for Standardization (GIS), The German AI Association, the Association of German Engineers, Germany’s digital industry association, the Fraunhofer Society for the Advancement of Applied Research and the Federal Association of German Industries. In addition, digital recordings of parliamentary debates as well as statements, policy papers and electoral programs of the larger opposition parties were reviewed. The perspectives of Germany’s subnational governments and civil society organizations, however, were out of the scope of the research project. Each of the following paragraphs consists of a presentation of a central aspect of the strategy, followed by an analysis of this aspect through the lens of liberal governmentality.

4 A human-centric AI

A key element of Germany’s AI strategy is the guiding vision (‘leitbild’) of a ‘human-centric AI’ that is oriented toward the benefit of every individual and society at large. This vision is mainly substantiated with numerous technoscientific promises (Joly 2010) echoing traditional framings of S&T as drivers of economic success and social progress: the economic impact of AI on manufacturing (being the foundation of Germany’s economic power), agriculture, energy and transport, the protection provided by AI-based IT security (being a crucial factor for the functioning of a digitalized economy), police work, emergency services and pandemic management, the potentials of integrating AI in medical diagnosis and robotic care work, and the use of AI for the efficient consumption of natural resources as well as the prediction of the behaviour of complex systems such as climate and mobility (AImiG, 16f.). However, several risks and potential harms that are commonly associated with AI are addressed as well. Particular attention is paid to the widespread fear that further development of AI-based production systems could either lead to mass unemployment or to the disqualification of work. Furthermore, AI could cause fatal car accidents and enable the manipulation of political opinion through chat-bots and deep-fakes. In addition, ethical expert opinion highlights the dangers of using biometric facial recognition and AI-based job recruiting tools with regard to the violation of the constitutionally established principles of equality and non-discrimination (DEC final report 2019; LS Ethik Briefing 2020, SCAI final report 2020). What is claimed to be at stake with the rise of AI, hence, are the prosperity, physical integrity, freedom of action and (informational) self-determination of Germany’s citizens. Consequently, the guiding vision of a human-centric AI addresses these risks and harms: instead of manipulating consumers and voters, replacing the workforce and threatening fundamental rights, the use of such an AI would focus on the well-being and dignity of citizens as well as the benefit of society at large (AImiG, 8). With regard to applications in economic contexts, a human-centric AI should support the development of skills and talents, creativity, self-determination, safety and health. Therefore, the strategy sets out the goal of a responsible development and use of AI that adheres to ethical and legal principles consistent with Germany’s liberal democratic constitutional system (AImiG, 9).

Beyond these official commitments to basic liberal principles, however, the relation between the vision of a human-centric AI and liberal political rationality is much more specific as the vision enacts an ordoliberal understanding of the conditionality of freedom and a social market economy. The integration of AI in society may fundamentally alter the given economic order as it could restrict the sovereignty of individual consumers or otherwise cause socially undesirable economic effects. In the face of an increasingly digital and algorithmic governing of the self and others, the ‘unintended consequences’ of AI applications (mass unemployment, discrimination of job applicants etc.) or its use for ‘malicious purposes’ (manipulation of consumers and public opinion, cybercrime, etc.) appear to become a new threat to freedom and the wealth of a the nation. Accordingly, the vision of human-centric AI promises to enable the well-being and freedom of citizens as well as the maintenance of the social market economy: firstly, by facilitating the satisfaction of ‘basic needs’ (wealth, health, security etc.); secondly, by enabling the rational and responsible exercise of individual freedoms. Thus, the guiding vision of a human-centric AI provides an ordoliberal account of the risks and benefits of AI.

5 Technological sovereignty

Risks and benefits also play a crucial role in the second key component of Germany’s AI strategy: the promise that nation-specific advancements in the R&D of AI would meet national (economic) interests and serve the nation’s global ambitions. In many technology areas, Germany has relied—and is still relying—on the availability of products and services on a global market. This is particularly true with regard to the digital infrastructures needed for AI applications. However, this dependency in the AI sector has been widely problematized as actors from all over the political spectrum call for a joint effort to push ahead innovation and capacity building in Germany to the level of ‘technological sovereignty’.Footnote 2 Within Germany’s AI strategy, the necessity to achieve technological sovereignty is legitimized by the global competition of nations that represent antagonistic understandings of the benefits and risks of AI (AImiG, 32). In 2016, the U.S. presented their National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan defining the government’s role predominantly as a facilitator of innovation. The National Artificial Intelligence Initiative of 2019 emphasized the importance of continued U.S. leadership in AI R&D. China, on the contrary, plans to use a state-driven development model as part of its Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence Plan, which was presented in 2017 and sets the goal to become the global leader in the field of AI by 2030, including in military AI. Given the market dominance and expansive strategies of big U.S.’s tech companies on the one hand and China’s endeavor to gain global leadership by means of technology policy, on the other hand, technological sovereignty in the AI sector is proclaimed as a way to secure the competitiveness of Germany’s economy and Europe as a whole (AImiG, 33). Therefore, the declared goal is not to re-strengthen economic protectionism or to achieve national autarky (LS Positionspapier 2020, 5–6). Instead, Germany’s economy would have to commit itself to global competition, all the more as public trust in and acceptance of a human-centric AI are seen as a competitive edge for the German economy since they are a prerequisite for the uptake of AI in society (GIS AI roadmap, 13). Here, technological sovereignty and a human-centric AI are imagined as mutually dependent: without technological sovereignty, a human-centric AI cannot be realized in the face of the global race to AI; but at the same time, a human-centric AI is the unique selling point of German products and services on global markets and, hence, the best way to achieve technological sovereignty.

Consequently, Germany should strive to become Europe’s leading global player in the R&D of AI, making ‘AI made in Germany’ a worldwide acknowledged trademark. This approach is proclaimed as the “third way” (SCAI final report, 231), as an alternative to the market-driven way of the U.S. where private actors play the central role in the innovation of AI and the state-capitalist path of China where the socialist party is the driving force behind R&D of AI.

Within Germany’s AI strategy, ‘technological sovereignty’ adds a geopolitical dimension to the vision of a human-centric AI: achieving technological sovereignty becomes a question of avoiding dependency on actors whose approaches to govern the disruptive potentials and shape the future of AI would differ significantly from the one of Germany. Albeit not explicitly criticizing U.S. big tech companies and the Chinese government, the strategy evokes fearful imaginaries of an AI-powered ‘surveillance capitalism’ based on the ‘digital screening’ and ‘manipulation’ of consumers for the sole purpose of profit and an AI-powered ‘surveillance state’ based on a meticulous behavioural control of all citizens for the purpose of maintaining social harmony (Aho and Duffield 2020). Against the background of these threat scenarios, it is not only the economic power and wealth of Germany that is claimed to be at stake but also the freedom and the fundamental rights of the nation’s citizens.

The race for AI supremacy, hence, is framed as a race between different forms of governing (with) AI that either threaten individual freedoms or protect them. A threat to individual freedom is either posed by a state using AI for restricting the freedom of its citizens or by private companies using AI to undermine the freedom of consumers. ‘The third way’ of governing (with) AI, on the contrary, would deliberately protect these freedoms and ensure a responsible and beneficial use of AI. By imagining a future that connects the techno-optimist vision of a human-centric AI with the fears of not achieving technological sovereignty in the AI sector, Germany’s AI strategy not only articulates the need to participate in the global race to AI but also a particular understanding of how to participate in this race. According to this understanding, the governing of AI has to operate between the twin dangers of governing too much (as in the case of autocratic government in China) and not governing enough (as in the case of neo-liberal government in the U.S.) (Dean 2010, 463). While the dangers of governing, too much are associated with the use of AI for excessive state interference with private (economic) activities, the dangers of not governing enough are associated with the failure to regulate the use of AI for private (economic) activities and to intervene in case of market failure. Only if a balance between governing too much and governing too little is maintained, the ‘third way’ and, hence, the vision of a human-centric AI can become a reality. This ‘third way’ of governing (with) AI transfers the ordoliberal concept of a ‘third way’ between laissez-faire liberalism and totalitarianism from the post-war era to the digital age.

6 Creating a dynamic AI ecosystem

Besides the imaginary of a human-centric AI, ordoliberal political rationality is enacted by the various practices of governing grouped under the framework of a ‘holistic’ Science, Technology & Innovation (ST&I) policy. This policy aims to strengthen Germany’s status as a center for AI research and to support Germany’s AI economy to become competitive in a global market (AImiG, 9). It is claimed that to reach this goal, two complementary obstacles have to be moved—a translation gap between AI research and AI innovations and a lack of trust in AI—both requiring a certain level of governmental activity. One of the central reference points of the framework is the diagnosis that Germany’s AI research holds an international ‘top position’ but that there are considerable problems with the transfer of research results into applications resulting in a ‘translation gap’. Hence, a so-called ‘transfer initiative’ (AImiG, 22) is to be launched to support companies in developing the potential that arises from German AI research and in successfully competing in the international market for AI-based products, services and business models.

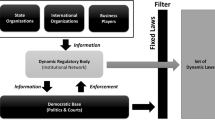

Here, the fear of failure to innovate and being left behind in global competition legitimizes governmental activities that go beyond ‘conventional forms’ of a liberal ST&I policy where the state serves as a mere financial facilitator of innovation. Essentially, the framework follows a ‘national innovation ecosystems’ approach (Fransman 2018) and aims to create a ‘dynamic AI-ecosystem’ (AImiG, 12). A ‘national innovation ecosystem’ models the complex relationships that are formed between actors (universities, business firms, venture capitalists, centers of excellence, funding agencies, policymakers, etc.) or entities (funds, equipment, facilities, etc.) of an ecosystem whose goal is to enable R&D and, most importantly, innovation. To raise the innovative performance of the ecosystem and to improve the competitive position of a national economy, the state acts at the front end of the innovation process by funding basic or mission-oriented research (within funding programs on problems of national importance or grand societal challenges).Footnote 3 Since staying outside of the innovation process would mean to not govern enough, the state has to actively shape the conditions for innovation by ‘fertilizing the interactions and linkages of multiple stakeholders in innovation ecosystems’ (Sun et al. 2019, 104). At the same time, by ‘only’ cultivating the innovative powers of the AI ecosystem the state does not govern too much, as would be the case with an innovation system based on state-owned enterprises and R&D facilities. Hence, the ST&I policy as it is envisioned in Germany’s AI strategy echoes the ordoliberal approach to ensure that market failures are remedied or do not occur in the first place. Here, market failure would be the failure to innovate. Given the assumption that an innovation ecosystem is far too complex to be planned or engineered, ordoliberal innovation policy limits itself to governing the rules of the game, which in turn allows the actors of the national innovation system to develop their own visions, set their own expectations and act accordingly. The state does not intervene directly in the economy nor does it interfere with the freedoms of economic players. In the terminology of governmentality studies, ordoliberal innovation policy follows the operational mode of environmentality that “seeks to govern the ‘environment’ of human and nonhuman entities rather than operating directly on ‘subjects’ and ‘objects’.” (Lemke 2021, 168) Environmentality is less concerned with targeting individual actions but rather seeks to alter the material conditions and contexts of these actions to manage performances and circulations (Foucault 2008, 259). Here, this environmental rationality aims to foster successful AI innovation by acting on its ecosystem.

7 Promoting trust in AI

However, successful innovation alone would not guarantee the realization of the goals of the envisioned ST&I policy, since a ‘lack of trust’ in AI would lead to a lack of diffusion, inhibit adoption and hamper the uptake of AI in society. Therefore, public trust in AI shall be promoted by establishing ‘an ethical, legal, cultural and institutional context which upholds fundamental social values and individual rights and ensures that the technology serves society and individuals’ (AImiG, 4). On the one hand, this would require raising awareness among stakeholders about the benefits of using AI. Consequently, the national strategy sets out the goal to initiate a societal dialog on AI that helps to create a solid knowledge base and, thus, leads to a more ‘fact-oriented’, ‘evidence-based’ and ‘objective’ debate as well as to establish participatory procedures that allow for public engagement with AI R&D. On the other hand, trust in AI could only be expected if only trustworthy AI applications that are secure, comply with ethical principles and meet legal requirements are developed and brought onto the market. Consequently, ‘ethics by, in and for design’ is highlighted as a central feature of a human-centric AI and, thus, of the trademark ‘AI made in Germany’. In the terminology of the EU’s High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG), ethics by design refers to a risk management through the implementation of ethical and legal principles from the beginning of the design process. Here, the aim is to manage the production of risks ‘upstream’, to inject societal and ethical considerations into the innovation process and to ensure that the political aims of and concerns with AI are integrated as they unfold. Understood as a method, ‘ethics by design’ helps to realize the ethically and legally compliant development and application of AI-based systems by creating ‘precise and explicit links between the abstract principles which the system is required to respect and the specific implementation decisions’ (High-level Group on Artificial Intelligence 2019, 21, see also Hälterlein 2021b). By adopting this ‘technological fix’ approach from the AI HLEG, the strategy envisions a soft regulatory tool that is in line with the market principle and may even become a unique selling point of an ‘AI made in Germany’.

However, trust in AI shall also be promoted by traditional regulatory instruments. Standards for auditing and impact assessments of AI applications (including ethical aspects) shall be developed by the GIS, which are then to be used for testing, inspection and conformity control by governmental and private-certification bodies. Since certification would provide for legal certainty, interoperability, IT security, and high (ethical) quality of AI products, it is seen as a trust-building measure that will have a positive impact on technology transfer and diffusion. Moreover, setting the standards on the international level is highlighted as a means to determine which products will be successful in global markets and, hence, raises the competitiveness of Germany’s economy.

While these various regulatory measures are put in place to “design a trust-inspiring framework and to ensure that this framework is complied with” (AImiG, 44), they should not inappropriately restrict or hinder innovation or otherwise disproportionately increase the costs for the development of AI solutions. To ensure this proportionality, a risk-based regulatory approach is preferred by political actors as well as in the reports of the expert commissions. This approach would differentiate applications of AI systems according to their criticality. ‘Criticality’ refers to the infringement of rights, to the extent of harm and to the degree of human autonomy that the use of an AI system might imply. An increasing criticality should go hand in hand with increasing requirements and increasing authority of the regulatory instruments. While there are ongoing discussions about whether 3 or 5 levels of criticality will provide enough flexibility, there is a consensus that mandatory legal requirements such as certification and conformity assessment by public authorities should only apply to those AI systems that are classified as ‘too risky’. For low-risk systems, however, only voluntary codes are envisioned. In case of a very high criticality, restrictions of use or even a legal ban might be issued.

In sum, the measures grouped under the framework of a holistic ST&I policy reflects the ordoliberal political rationality that offers a ‘third way’ between laissez-faire liberalism and authoritarianism. The bridging of the translation gap between AI research and AI innovations, on the one hand, cannot be realized by a strict limitation of government as in the case of laissez-faire liberalism. Instead, it requires a certain degree of governmental activity. A ‘dynamic AI ecosystem’ can only emerge and produce its effects under certain conditions that have to be carefully constructed. Therefore, the task of the ordoliberal innovation policy is to eliminate all disturbing influences that could stand in the way of innovation and to create an environment that nurtures the innovative culture of a national economy. At the same time, however, these governmental measures differ from excessive state interference with economic activities and the market mechanism under the sign of an authoritarian government. In terms of promoting trust in AI, governing too much would mean overregulating entrepreneurial activities and, consequently, failing to unlock Germany’s full innovative potential while not governing enough would result in the failure to guarantee that only trustworthy AI products and services are brought onto the market. From the perspective of governmentality studies, the risk-based approach to governing AI has to be understood as constituting a security apparatus since its problematization follows the model of an economic calculation: it offsets the benefits of regulating AI for the purpose of trust-building with its costs and seeks to maximize the positive elements of intervening in the market while minimizing what is risky about it. In this reflexive modality of governing risk, state activity in the AI sector is seen as unproblematic as long as it stays within economically acceptable limits. Essentially, this security apparatus produces an assessment of fears: weighting the fear of the failure to innovate with the fear of the ‘unintended consequences’ of innovation.

8 Critical engagements

By applying the governmentality concept to Germany’s national AI strategy, this paper does not only provide an understanding of the nexus between the design and implementation of this strategy on the one hand, and ordoliberal political rationality on the other hand. The concept also enables us to critically engage with the politics of AI futures. In the remainder of this paper, I will conduct two lines of critical investigation.

The first line of critique focuses on the relationship between freedom and security as it is arranged within (ordo)liberal government. Germany’s AI strategy frames the race to AI supremacy as a race between different approaches to governing (with) AI. Germany’s own approach, the ‘third way’, gains its persuasiveness against the backdrop of the two threat scenarios of an excessive AI-powered surveillance capitalism and an excessive AI-powered surveillance state. However, studies of governmentality have shown that illiberal modes of governing are not a deviation or exception from liberal rule. Instead, the potentially unlimited and excessive exercise of state power is the way, liberal government organizes the boundaries of freedom in the name of security (Opitz 2010). A legally binding framework on AI is still pending in Germany but will have to implement the legislation currently under negotiation in the European Union.Footnote 4 It is therefore instructive to have a closer look at the EU’s AI act to anticipate future legislation in Germany.

After the European Commission presented an initial proposal for the regulation of AI applications at EU level in 2021, an intense controversy arose during the legislative process. While business associations and security agencies argued for the absence of a binding legal framework and intervened accordingly, the European Parliament made extensive amendments to the proposal in summer of 2023 to strengthen the protection of fundamental rights. Certain AI practices should be banned as they would not be compatible with the fundamental rights and values applicable in the EU—for instance the use of AI for the purpose of social scoring, behaviour/decision manipulating, predictive profiling of potential (re)offenders and real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces (pp 128–129). However, in the compromise version of December 2023 agreed by the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission instead of a general ban, a number of exceptions are defined where security interests would outweigh the risks, for instance, when the use of real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces serves the prevention of terrorist attacks or the search for missing persons and when ex-post remote biometric identification is used for the investigation of criminal offenses. Here, an AI-based mass surveillance (hardly distinguishable from that in China) is legitimized as the necessary downside of liberal freedoms since it is employed to defend the very conditions under which these freedoms can be exercised—which is precisely the argument used by German Federal Criminal Police Office and German Federal Police to legitimize test runs of biometric facial recognition systems at two railway stations in 2006 and 2017. The promise and expectation of providing security through the use of this technology is essentially based on the assumption that these systems are highly accurate. However, this assumption has to be put into perspective in view of previous tests of biometric facial recognition under realistic conditions. Moreover, its use by police forces reproduces or even reinforces racial profiling and other forms of discriminatory practices (Hälterlein 2023).

The same holds for a number of applications that slightly differ from those mentioned in the EU proposal, but are no less problematic than those that will likely fall under a legislative ban. These include the use of AI for predictive policing that does not aim at identifying potential (re)offenders but at identifying potential places of futures crimes—an approach that is used by many police departments in Germany, even though it’s use by US police forces has been criticized as being largely ineffective and for reproducing or even reinforcing over-policing and discrimination of minorities (Hälterlein 2021a; Lum and Isaac 2016). Another application of AI for surveillance and social control purposes is video analytics where the aim is not to identify a search-listed individual but to single out ‘suspicious’ or ‘deviant’ behaviour. This approach is currently tested in two German cities albeit it has been criticized for being premature in terms of high failure rates and for imposing implicit standards of ‘normal’ or ‘desired’ behaviour instead of aiding police forces to prevent crimes (Vermeulen and Bellanova 2013). Hence, even within the legal boundaries that the European AI act would define, certain forms of intrusive AI-based surveillance of citizens would still be possible in Germany—forms of intrusive AI-based surveillance that are already applied or tested by German state authorities. Since these technologies are neither accurate nor would they perform equal on all surveillance subjects, their application would not increase the security of citizens and would therefore restrict civil liberties for no good reason.

Even more problematic, however, is the use of AI-based surveillance technologies on Europe’s external borders and the envisioned use of AI-based military technology by European armed forces (including those of Germany) which demonstrates terrifyingly how the ‘protection’ of an area of liberal freedom, peace and security correlates with the systematic violation of human rights or even the extinction of human lives. Strikingly, both border security and military applications of AI are deliberately excluded from EU regulation and the German AI strategy.

Finally, recent work on ‘digital colonialism’ (Kwet 2019) has shown that AI is reinforcing old and new colonial power relations. While Germany fears becoming ‘colonized’ by global AI powers, it ignores that it is already a neo-colonial power within global AI infrastructures and value chains. Here, illiberal practices in the Global South are tolerated or even supported as long as they contribute to upholding the liberal way of life for those who can afford it (Crawford 2021). As Aradau and Blanke (2022, 142) recall, “[t]he organizations calling for or implementing AI ethics remain largely silent over what ‘fundamental rights’ might look like, as rights are hardly ever subject to ‘consensual application’. Rather, rights are claimed by different subjects in variable situations and often against considerable resistance. Moreover, there is no abstract human who is a subject of rights as envisaged by the ethics reports and guidelines. Human rights’ discourses enact a version of the ‘human’, which excludes multitudes of others deemed ‘lesser humans’.”

Considering the dark sides of liberal governing (with) AI and Germany’s involvement in them, the credibility of a ‘third way’ becomes more than questionable and with it, the legitimacy of Germany’s aspirations to become a leading global player in the R&D of AI.

The second line of critique focuses on the governmental self-limitation of liberalism. Since the liberal state has to respect economic decisions as the result of a legitimate pursuit of self-interests and an expression of free will, it should respect the individual or collective decision against the uptake or implementation of AI accordingly. However, as Pfotenhauer and Juhl have stressed, ST&I policies typically display a ‘pro-innovation bias’ and do not treat the rejection of new technology “as an expression of political will and hence intrinsically valuable and subject to safeguarding by the state” (2017, 76). As part of its national AI strategy, the federal government intends to put up a communication strategy and introduces regulatory measures to promote trust in AI and, thereby, excludes mistrust in AI from the spectrum of rational choices and democratic options. This is also reflected in the fact that there are no NGOs or representatives of civil society in the steering committee and the working groups of the Learning Systems Platform. Accordingly, the ‘Stiftung Neue Verantwortung’, a non-profit think tank, criticized that social stakeholders are not sufficiently involved in the state-organized and state-initiated dialog on AI in Germany (LS Online-Konsultation 2018). Here, the imagination of a particular AI future is played out against the liberal democratic imaginary of a self-determined individual who can participate in the self-governance of the community it is part of (Ezrahi 2012). It is, therefore, not considered an open question whether to integrate AI in society but only how to integrate AI in society. This policy of depoliticization of the future of AI rather resembles a nineteenth century humanitarianism of helping those who are deemed unable to act in their own best interest than a liberal protection of individual freedoms and limitation of state power. Against the backdrop of these fundamental principles of liberal government, Germany’s national AI strategy can be criticized as paternalistic. The ordoliberal understanding of the conditionality of freedom becomes synonymous with a lack of trust in Germany’s citizens.

9 Conclusion

National AI strategies articulate imaginaries of the integration of AI into society and envision the governing of AI research, development and applications accordingly. To integrate these central aspects of national AI strategies under one coherent perspective, the paper presented an analysis of Germany’s strategy ‘AI made in Germany’ through the conceptual lens of ordoliberal political rationality. By promoting the guiding vision of a human-centric AI, the strategy not only adheres to ethical and legal principles consistent with Germany’s liberal democratic constitutional system but also addresses risks and promises in a way inherent to the ordoliberal understanding of the conditionality of freedom. Against this background, the strategy cultivates the fear of not achieving technological sovereignty in the AI sector and, thus, becoming dependent on global players—both big tech and illiberal states—whose approaches to leverage the power of AI would significantly differ from the one of Germany. This framing of the race to AI as a race to technological sovereignty is used to articulate the ordoliberal way to governing AI—the ‘third way’. According to this ‘third way’, government has to operate between the twin dangers of governing too much (as in the case of authoritarian government in China) and not governing enough (as in the case of neo-liberal government in the U.S.). This logic of a ‘third way’ structures Germany’s ST&I policy as well. While not governing enough would result in the failure both to innovate and to promote trust among citizens, governing too much would result in the overregulation of entrepreneurial activities and a lock-in of Germany’s innovative potential. By proposing a risk-based approach to regulating AI, the strategy implements a security apparatus as it produces an assessment of fears: weighting the fear of the failure to innovate with the fear of the ramifications of innovation.

Beyond its analytical prowess, the governmentality concept enabled the articulation of two lines of critical investigation. The first line focuses on the relationship between freedom and security as it is arranged within (ordo)liberal government. The second line focuses on the governmental self-limitation of liberalism. As a result of these investigations, it was shown that the credibility of the ‘third way’ is more than questionable and Germany’s national AI strategy has paternalistic traits. However, it is an open question of how to move beyond this problematic way of imagining and governing AI. What are desirable alternatives, alternatives that are equally committed to human values and human well-being but less fixated on global competitiveness and national security, and less prone to reproducing forms of othering and exclusion? Answering this question remains an urgent task for the powers of imagination. In the course of envisioning alternative AI futures, it will probably be inevitable to imagine alternative ways of governing beyond (ordo)liberal rationality as well.

Notes

The documents analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The origins of this term can be traced back to the late 1970s. At that time, the Canadian Science Council warned against not letting the dependence on foreign technological know-how become too great because this could endanger national sovereignty. In macro-economic contexts, technological sovereignty is defined as „the capability and the freedom to select, to generate or acquire and to apply, build upon and exploit commercially technology needed for industrial innovation.“ Grant (1983).

According to a linear model of innovation, the results of this research will be taken up through applied R&D by private actors, leading to marketable products and, ultimately, their diffusion and utilization in society. This process would quasi-automatically generate technological change, economic growth and prosperity, all of which are considered essential components of social progress and the (global) public good. See for instance: Godin (2006), Schot and Steinmueller (2018).

Member States have two years to adopt applicable EU law into national law.

References

Aho B, Duffield R (2020) Beyond surveillance capitalism: privacy, regulation and big data in Europe and China. Econ Soc 49(2):187–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2019.1690275

Anderson B (2010) Preemption, precaution, preparedness: anticipatory action and future geographies. Prog Hum Geogr 34(6):777–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510362600

Aradau C, Blanke T (2022) Algorithmic reason: the new government of self and others. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192859624.001.0001

Bareis J, Katzenbach C (2021) Talking AI into being: the narratives and imaginaries of national AI strategies and their performative politics. Sci Technol Hum Values:016224392110300. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211030007

Barry A (2001) Political machines: governing a technological society, 1 publ. Athlone Press, London

Berghahn V, Young B (2013) Reflections on Werner Bonefeld's 'Freedom and the Strong State: On German Ordoliberalism' and the continuing importance of the ideas of ordoliberalism to understand Germany's (contested) role in resolving the Eurozone Crisis. New Polit Econ 18(9):768–778

Biju PR, Gayathri O (2023) The Indian approach to Artificial Intelligence: an analysis of policy discussions, constitutional values, and regulation. AI Soc Adv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01685-2

Borch C (2017) Algorithmic finance and (limits to) governmentality: on Foucault and high-frequency trading. Le Foucaldien 3(1):6. https://doi.org/10.16995/lefou.28

Carriço G (2018) The EU and artificial intelligence: a human-centred perspective. Eur View 17(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1781685818764821

Cath C, Wachter S, Mittelstadt B, Taddeo M, Floridi L (2018) Artificial intelligence and the ‘good society’: the US, EU, and UK approach. Sci Eng Ethics 24(2):505–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9901-7

Chatterjee S (2020) AI strategy of India: policy framework, adoption challenges and actions for government. Transform Gov People Process Policy 14(5):757–775. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-05-2019-0031

Crawford K (2021) Atlas of AI: power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press, New Haven, London

Dean M (2010) Power at the heart of the present: exception, risk and sovereignty. Eur J Cult Stud 13(4):459–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549410377147

Drake F (2011) Protesting mobile phone masts: risk, neoliberalism, and governmentality. Sci Technol Human Values 36(4):522–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910366149

Ebers M, Hoch VRS, Rosenkranz F, Ruschemeier H, Steinrötter B (2021) The European commission’s proposal for an artificial intelligence act—a critical assessment by members of the robotics and AI law society (RAILS). J 4(4):589–603. https://doi.org/10.3390/j4040043

European Commission (2021) Proposal for a regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (artificial intelligence act) and amending certain union legislative acts: DRAFT compromise amendments on the draft report. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0206

European Parliament (2023) Artificial intelligence act: amendments adopted by the European parliament on 14 June 2023 on the proposal for a regulation of the European parliament and of the council on laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (artificial intelligence act) and amending certain union legislative acts. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2023-0236_EN.html

Ezrahi Y (2012) Imagined democracies: necessary political fictions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=480321

Floridi L (2021) The European legislation on AI: a brief analysis of its philosophical approach. Philos Technol:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00460-9

Foffano F, Scantamburlo T, Cortés A (2023) Investing in AI for social good: an analysis of European national strategies. AI Soc 38(2):479–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01445-8

Foucault M (2007) Security, territory, population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–78 (Burchell G, Trans). Lectures at the Collège de France. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York, NY. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0619/2006048887-d.html

Foucault M (2008) The birth of biopolitics: lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–79. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Fransman M (2018) Innovation ecosystems. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108646789

Godin B (2006) The linear model of innovation. Sci Technol Hu Values 31(6):639–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243906291865

Grant P (1983) Technological sovereignty: forgotten factor in the ‘hi-tech’ razzamatazz. Prometheus 1(2):239–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/08109028308628930

Hagendorff T (2020) The ethics of AI ethics: an evaluation of guidelines. Mind Mach 30(1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09517-8

Hälterlein J (2021a) Epistemologies of predictive policing. Mathematical social science, social physics and machine learning. Big Data Soc. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211003118

Hälterlein J (2021b) Technological expectations and the making of Europe. Sci Technol Stud. https://doi.org/10.23987/sts.110036

Hälterlein J (2023) Facial recognition in law enforcement. In: Borch C, Pardo-Guerra JP (eds) The Oxford handbook of the sociology of machine learning. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197653609.013.25

High-level Group on Artificial Intelligence (2019) Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. European Commission website. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai

Hine E, Floridi L (2022) Artificial intelligence with American values and Chinese characteristics: a comparative analysis of American and Chinese governmental AI policies. AI Soc Adv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01499-8

Introna LD (2016) Algorithms, governance, and governmentality. Sci Technol Hum Values 41(1):17–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915587360

Joly P‑B (2010) On the economics of techno-scientific promises. In Madeleine Akrich YBFMPM (ed), Débordements: Mélanges offerts à Michel Callon. Presses des Mines, Paris, pp 203–221. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pressesmines.747

Köstler L, Ossewaarde R (2022) The making of AI society: AI futures frames in German political and media discourses. AI Soc 37(1):249–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01161-9

Kwet M (2019) Digital colonialism: US empire and the new imperialism in the Global South. Race Class 60(4):3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396818823172

Lemke T (2021) The government of things: Foucault and the new materialisms. New York University Press, New York

Lum K, Isaac W (2016) To predict and serve? Significance 13(5):14–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2016.00960.x

Miller P (2008) Calculating economic life. J Cult Econ 1(1):51–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350801913643

Opitz S (2010) Government unlimited: the security dispositif of illiberal governmentality. In: Bröckling U, Krasmann S, Lemke T (eds) Governmentality: current issues and future challenges. Routledge, New York, pp 101–122

Ossewaarde M, Gulenc E (2020) National varieties of artificial intelligence discourses: myth, utopianism, and solutionism in west European policy expectations. Computer 53(11):53–61. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2020.2992290

Paltieli G (2022) The political imaginary of national AI strategies. AI Soc 37(4):1613–1624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01258-1

Pfotenhauer S, Juhl J (2017) Innovation and the political state: beyond the facilitation of technologies and markets. In: Godin B, Vinck D (eds) Critical studies of innovation: alternative approaches to the pro-innovation bias. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp 68–93

Radu R (2021) Steering the governance of artificial intelligence: national strategies in perspective. Policy Soc 40(2):178–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2021.1929728

Roberts SL, Elbe S (2017) Catching the flu: syndromic surveillance, algorithmic governmentality and global health security. Secur Dialogue 48(1):46–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010616666443

Roberts H, Cowls J, Hine E, Mazzi F, Tsamados A, Taddeo M, Floridi L (2021a) Achieving a ‘good AI society’: comparing the aims and progress of the EU and the US. Sci Eng Ethics 27(6):68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00340-7

Roberts H, Cowls J, Morley J, Taddeo M, Wang V, Floridi L (2021b) The Chinese approach to artificial intelligence: an analysis of policy, ethics, and regulation. AI Soc 36(1):59–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-00992-2

Rose N (1998) Inventing our selves: psychology, power, and personhood. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rouvroy A, Berns T (2013) Gouvernementalité algorithmique et perspectives d’émancipation: algorithmic governmentality and prospects of emancipation. Disparateness as a precondition for individuation through relationships? Réseaux 177(1):163–196

Sally R (1996) Ordoliberalism and the social market: classical political economy from Germany. New Polit Econ 1(2):233–257

Savage N (2020) The race to the top among the world’s leaders in artificial intelligence. Nature 588(7837):S102–S104. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03409-8

Schot J, Steinmueller WE (2018) Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Res Policy 47(9):1554–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011

Smuha N, Ahmed-Rengersb E, Harkens A, Li W, MacLaren J, Pisellif R, Yeungg K (2021) How the EU can achieve legally trustworthy AI: a response to the European commission’s proposal for an Artificial Intelligence act. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3899991

Sun SL, Zhang Y, Cao Y, Dong J, Cantwell J (2019) Enriching innovation ecosystems: the role of government in a university science park. Global Transitions 1:104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glt.2019.05.002

Tironi M, Valderrama M (2021) Experimenting with the social life of homes: sensor governmentality and its frictions. Sci Cult 30(2):192–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2021.1893682

Veale M, Zuiderveen Borgesius F (2021) Demystifying the draft EU artificial intelligence act: analysing the good, the bad, and the unclear elements of the proposed approach. Comput Law Rev Int 4:97–112

Vermeulen M, Bellanova R (2013) European ‘smart’ surveillance: what’s at stake for data protection, privacy and non-discrimination? Secur Hum Rights 23(4):297–311. https://doi.org/10.1163/18750230-99900034

Walters W, Tazzioli M (2023) Introduction to the handbook on governmentality. In Walters W (ed) Research handbooks in political thought. Handbook on governmentality. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 1–20

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Fritz Thyssen Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author states there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hälterlein, J. Imagining and governing artificial intelligence: the ordoliberal way—an analysis of the national strategy ‘AI made in Germany’. AI & Soc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01940-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01940-0