Abstract

The individual physical appearances of robots are considered significant, similar to the way that those of humans are. We investigated whether users prefer robots with male or female physical appearances for use in daily communication situations and whether egalitarian gender role attitudes are related to this preference. One thousand adult men and women aged 20–60 participated in the questionnaire survey. The results of our study showed that in most situations and for most subjects, “males” was not selected and “females” or “neither” was selected. Moreover, the number of respondents who chose “either” was higher than that who chose “female.” Furthermore, we examined the relationship between gender and gender preference and confirmed that the effect of gender on the gender preference for a robot weakened when the human factor was eliminated. In addition, in some situations for android-type robots and in all situations for machine-type robots, equality orientation in gender role attitudes was shown to be higher for people who were not specific about their gender preferences. It is concluded that there is no need to introduce a robot that specifies its gender. Robots with a gender-neutral appearance might be more appropriate for applications requiring complex human–robot interaction and help avoid reproducing a gender bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The influence of humans’ physical appearances on other humans has been displayed in previous psychology studies (Mims et al. 1975; Walster et al. 1966). Similarly, the physical appearances of robots have a significant effect as well. In fact, it has been shown that android-type robots (robots that look exactly like humans) are preferred as communication partners to mechanical-type robots (robots that are similar to humans in figure but have a metallic or mechanical appearance) and humans in sports/exercise situations(Suzuki et al. 2021a, b). Other studies have also mentioned the effect of the physical appearances of robots in many situations (Goetz et al. 2003; Hinds et al. 2004; Nishio et al. 2012; Abubshait and Wiese 2017; Suzuki et al. 2021a, b). Thus, it is important to consider the physical appearance of robots when introducing them into our daily lives because their appearance can be an important factor when facilitating interaction with humans.

There are numerous aspects to physical appearance; the one that influences gender assignment cannot be ignored. Robots are characterized by their physicality, which makes it easy for humans to assign gender arbitrarily. Therefore, the problems associated with gender-specific properties (so-called ‘gendered robots’) should be carefully examined and discussed. The interaction between robots and humans in daily life applications should be considered to determine whether humans prefer robots with the same or a different gender. In addition to existing studies suggesting that males generally express positive responses towards robots more than females do (Nomura et al. 2006, 2008; Kuo et al. 2009; Lin et al. 2012), the effect of the gender of robots on human psychological and behavioral reactions toward these robots has been examined. For example, a comparison experiment between a mechanical humanoid robot and an android with a female appearance indicated that university students preferred female robots for domestic use (Carpenter et al. 2009).

Furthermore, previous studies have indicated that men and women tend to prefer robots with female features and male features, respectively, suggesting cross-gender effects. For example, in an experiment in which a humanoid robot had a non-gendered appearance and its gender was manipulated by voice quality, visitors were asked to make a monetary donation and answer a questionnaire. The results showed a cross-gender effect in that male participants were more likely to donate money to the female robot than women were. Moreover, male participants rated female robots as more credible and trustworthy than male robots, whereas the converse was observed with female participants (Siegel et al. 2009). In another experiment in which participants solved puzzles while cooperating with a doll robot that had a non-gendered appearance and gendered voice and name, a cross-gender effect was similarly observed; participants interacting with the robot of a different gender felt more comfortable than those who interacted with the robot of the same gender (Alexander et al. 2014). This effect was also observed in an experiment in which a navigation task was performed in a town using computer-mediated communication between human instructors and robot followers (Koulouri et al. 2012).

Although robots assigned to people of a different gender were evaluated more positively, some studies have shown that robots assigned to people of the same gender were evaluated more preferably instead. For example, an experiment in which items were sorted on a touch-screen table using instructions given by a small-sized humanoid robot, whose gender was changed using computer-generated voices and names, indicated that female participants completed the task equally fast regardless of the gender of the robot, whereas male participants were faster in completing the task when the robot was male (Kuchenbrandt et al. 2014). This means that the interaction between humans robots may differ depending on various types of interaction factors, such as the nature of the situation or task.

Furthermore, the reason behind people’s preference for a certain gender of robot may lie behind the gender stereotyping of people toward one another. For example, a common gender stereotype is based on hair length, and female robots with long hair are considered more communal than male robots with short hair (Eyssel and Hegel 2012). They also reported that tasks that were considered stereotypically male, such as heavy lifting and machine operation, were perceived to be more suitable for male robots. Furthermore, a gender stereotype existed in occupations; male robots were preferred in security-related occupations and female robots were preferred in healthcare-related occupations (Tay et al. 2014).

The effect of a robot’s gender on a user’s decision to use it is assumed to depend on these factors: the characteristics of the robot and the user's cultural expectations of the robot. The preferred gender of a robot may vary depending on differing factors such as the nature of situations and roles. The situational factors related to a robot’s gender need to be taken into account when considering introducing robots into daily life.

Although the issue of gender stereotyping in robots has been highlighted and its effects are becoming increasingly recognized, the roles and situations in which it occurs remain unclear, raising the question of what the gendered expectations for robots are. In addition, there is limited knowledge on whether these gender stereotypes are related to the existing gender stereotypes of people. The impact of a robot’s gender may depend on many factors, such as situational factors (e.g., nature of tasks), human factors (e.g., gender), and culture. Therefore, gender preferences in robotics designs also may depend on the nature of the interactions between humans and robots and the situations in which they interact.

The purpose of this study is to clarify whether people prefer robots with male or female physical appearances in regular communication situations and whether egalitarian gender role attitudes are related to this preference. Furthermore, in this study, we compared these tendencies for robots and humans.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

One thousand adult men and women aged 20–60 years (500 men and 500 women, 200 in each 10-year age range) participated in the study.

2.2 Questionnaire

2.2.1 Communication situations

From the communication situations used in a previous study (Suzuki et al. 2021a, b), those situations in which the percentage of respondents who selected an android-type robot or a mechanical-type robot was higher than that of a human were selected.

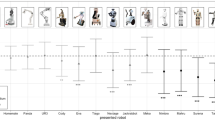

Situation sets A and B refer to those with android-type robots and mechanical-type robots, respectively. Situation set A contains tasks and communication that are relatively complex, whereas situation set B contains ones that are relatively simple. The details of each situation are presented in Table 1. In addtion sample images of the robots were shown to the respondents so that they could easily identify the android- and mechanical-type robots (each image are shown in Fig. 1). In this survey, the android- type robot was defined as “a robot that looks exactly like a human,” and the mechanical-type robot was defined as “a robot that is similar to a human but has a physical appearance consisting of metal and machinery.”

2.2.2 Gender preferences

-

Gender preference for humans:

In each situation, the respondents were asked to choose whether they wanted to interact with a person of the same or a different gender in each situation, with the following options: “I want to interact with a person of the same gender,” “I don't mind either,” and “I want to interact with a person of a different gender.”

-

Gender preference for robots:

For the android-type robot, the respondents were asked to make choices similar to the ones they did previously when choosing which kind of people to interact with based on their gender. For the mechanical-type robot, we asked for responses in the same way.

2.2.3 Short form of the scale of egalitarian gender role attitudes (SESRA-S; Suzuki 1994)

This is a psychological scale that comprised 15 items and was used to measure equality orientation in the gender role attitudes of men and women; responses were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale with options ranging from “1. strongly disagree” to “5. strongly agree” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89). This scale consists of items such as “Women should continue to work even after having children” and “If a wife has a job, it is not good because it increases the burden on her family” (reversed item). The higher the score, the greater is the degree of the equality orientation in gender role attitudes.

2.3 Procedure

The survey was conducted in October 2020 by monitors registered with a web-based survey company (iBRIDGE Corporation. This study was approved by an ethics review committee. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

3 Results

Prior to the subsequent analysis, the answers regarding gender preference were converted from “same gender” and “different gender” to “male,” “female,” and “neither” based on the gender of the respondent. Then, they were used for the analysis.

3.1 Proportion of gender preferences

First, we summarized the gender preference ratios for humans and android-type robots in situation set A. In most of situation set A, “either” and “female” were selected by more than 90% respondents for android-type robots and “either” was selected slightly more often than “female,” and the same trend was observed in the selection of humans. The results of this summary of gender preference ratios for android-type robots are shown in Fig. 2.

We summarized the gender preference ratios for humans and mechanical-type robots in situation set B. In situation set B, “either” and “female” were selected by more than 90% of the respondents for the mechanical-type robots and “either” was selected by 80% of them; the same trend was observed in the selection of humans. The results of this summary of the gender preference ratios for the mechanical-type robots are shown in Fig. 3.

3.2 Association between participants’ genders and gender preferences

Using the data of situation set A, we examined the association between the participants’ genders and their gender preferences. The associations between the gender and gender preference for humans, gender and gender preference for android-type robots, and gender preference for humans and gender preference for android-type robots are shown in Table 2. For some situations, the gender preferences for humans differed according to the participant’s gender, but the gender preferences for android-type robots did not differ considerably. The results also showed that a relationship existed between the gender preference for humans and the gender preference for robots.

Using the data of situation set B, we examined the association between participants’ genders and gender preferences (Table 3). In all situations, the gender preferences for both humans and mechanical-type robots did not differ based on the participant’s gender. The results also showed that a relationship existed between gender preferences for humans and for robots, similar to the data of situation set A.

3.3 Egalitarian gender role attitudes according to participants’ genders and gender preferences

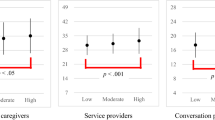

Figure 4 shows the descriptive statistics of the SESRA-S score according to participants’ genders and the gender preferences for android-type robots in situation set A (that of humans is shown in Table 8 in Appendix). A two-factor analysis of variance was conducted with the participants’ genders and gender preferences as independent variables and the SESRA-S score as the dependent variable in situation set A. Note that the percentage of ‘male’ being chosen as the preferred gender was very small (a few % in most cases), so it was excluded from the analysis. The results indicated that the effect of gender was significant in all situations, while the main effect of gender preference, and the interaction effect on the gender preferences for humans was not significant in all situations (Table 4). The results indicated that the effect of gender was significant in all situations, the main effect of gender preference was significant in a single case, and the interaction effect on the gender preferences for the android-type robots was not significant in all situations (Table 5).

Figure 5 shows the descriptive statistics of the SESRA-S score according to the participants’ genders and the gender preferences for the mechanical-type robots in situation set B (that of humans is shown in Table 9 in Appendix). A two-factor analysis of variance was conducted in situation set B similar to situation set A. The results indicated that the main effect of the participants’ genders was significant for all situations, the main effect of gender preference was significant in one case, and the interaction effect on the gender preferences for humans was not significant in all situations (Table 6). The results indicated that the main effects of participants’ genders and gender preferences were significant in all situations, and the interaction effect on the gender preferences of the mechanical-type robots was not significant in all situations (Table 7).

4 Discussion

In this study, we aimed to clarify whether people prefer robots with male or female appearances in communication situations and whether equality orientation in gender role attitudes is related to this preference. We also compared the results obtained with the gender preferences of humans.

4.1 Tendency of gender preference

First, we checked the ratios of human, android-type robots, and mechanical-type robots that were selected, and the results showed that, in any situation and for any subject, “males” was not selected, and “females” or “neither” was selected. Furthermore, the number of respondents who chose “either” was higher than that who chose “female”; This was more noticeable in situations with simple tasks included in situation set B and more for robots than for people. In other words, in terms of users' needs, genders do not need to be assigned to robots when introducing them into daily life. It may be a good idea to introduce a robot with a gender-neutral physical appearance to prevent the reproduction of gender stereotypes in robots.

When the relationship between participants’ genders and gender preferences was examined, we confirmed that the effect of gender on the gender preference of a robot weakened when the human factor was eliminated. In situation set A, even if the object was a human, the participant’s gender had a slight effect on the preference, but if the object was an android-type robot, the effect was weaker. In addition, in situation set B, there was almost no preference based on participants’ genders, even if the object was a human. This means that regardless of one's own gender, the expected gender differed depending on the content of the task. Even if gender preference may differ in different situations, if the physical anthropomorphic properties of the robot are reduced, the influence of the gender preference of the user will become weaker. Therefore, to prevent the reproduction of gender stereotypes in robots, making this elimination in the design may be a simple solution.

In both situation sets, the association between the gender preference for humans and both types of robots was found to be moderate, and the strength of the association was comparable. In other words, those who tended to prefer a particular gender of robots also tended to prefer a particular gender of humans. Similarly, we suggest that people who do not have a gender preference for humans are less likely to have one for robots. Thus, it is possible that assigning genders to robots may not necessarily increase gender bias.

4.2 Egalitarian gender role attitudes according to participants’ genders and gender preferences

In addition, in some situations for android-type robots and in all situations for machine-type robots, the equality orientation in gender role attitudes was shown to be higher for those who were not specific about their preference for a robot’s gender. Therefore, people with a low gender bias were less likely to have a gender bias toward robots, and the introduction of a robot with a specific gender did not increase any gender bias. In this regard, the problem is not associated with the design of the robot but the gender bias that people already have toward one another. Therefore, to intervene in and solve the problem of gender bias against robots, educating people about gender bias is an effective solution. Moreover, for people with a pre-existing gender bias, the introduction of gender in the design of a robot may increase this bias. It is important to examine this point in the future.

Although it has been reported that gendered robots may lead to the reproduction of gender stereotypes (Marchetti-Bowick 2009; Robertson 2010; Weber and Bath 2007), the present results do not suggest this, at least not in the context of this empirical study. An investigation into whether this is related to the culture of Japan or whether it is limited to the situation examined in this study will need to be conducted in the future.

The results also showed that numerous respondents did not prefer the gender of their communication robot. Based on this viewpoint, there is no need to introduce a robot that specifies its gender, thereby preventing the reproduction of gender stereotypes.

4.3 Implications

In Japan, when robots are introduced into daily life, there is no need to give them a specific gender appearance. Although providing a robot with a feminine appearance may be preferable to some due to past traditions, presently, it may be more appropriate to introduce robots with a gender-neutral appearance to avoid reproducing any gender bias. There is also the possibility that introducing these kinds of robots will be more acceptable abroad. Certainly, there may be cases where it is better to assign a gender depending on the characteristics of the situation or purpose, but it should be done with careful consideration.

References

Abubshait A, Wiese E (2017) You look human, but act like a machine: agent appearance and behavior modulate different aspects of human–robot interaction. Front Psychol 8:1393

Alexander E, Bank C, Jessica JJ et al (2014) Asking for help from a gendered robot. In: CogSci p ed. Proceedings of the 36th annual conference of the Cognitive Science Society Austin, Quebec City, Que, Canada Cognitive Science Society, TX; July 23–26, 2014, pp 2333–2338

Carpenter J, Davis JM, Erwin-Stewart N et al (2009) Gender representation and humanoid robots designed for domestic use. Int J Soc Robot 1:261–265

Eyssel F, Hegel F (2012) (S)he’s got the look: gender stereotyping of robots. J Appl Soc Psychol 42:2213–2230

Goetz J, Kiesler S, Powers A (2003) Matching robot appearance and behavior to tasks to improve human–robot cooperation. In: IEEE international workshop on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN2003), Nov 2, Millbrae, CA, pp 55–60

Hinds PJ, Roberts TL, Jones H (2004) Whose job is it anyway? A study of human–robot interaction in a collaborative task. Hum Comput Interact 19:151–181

Koulouri T, Lauria S, Macredie RD, Chen S (2012) Are we there yet? The role of gender on the effectiveness and efficiency of user–robot communication in navigational tasks. ACM Trans Comput Hum Interact 19:1–29

Kuchenbrandt HD, Häring M, Eichberg J (2014) Keep an eye on the task! How gender typicality of tasks influence human–robot interactions. Int J Soc Robot 6:417–427

Kuo IH, Rabindran JM, Broadbent E et al (2009) Age and gender factors in user acceptance of healthcare robots. In: Proceedings of the 18th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication. September 27 RO-MAN’09. Japan: Toyama IEEE, Piscataway, NJ; October 2, 2009, pp 214–219

Lin CH, Liu EZF, Huang YY (2012) Exploring parents’ perceptions towards educational robots: gender and socio-economic differences. Br J Educ Technol 43:E31–E34

Marchetti-Bowick M (2009) Is your Roomba male or female? The role of gender stereotypes and cultural norms in robot design. Intersect: The Stanford. Sci Technol Soc 2:90–103

Mims PR, Hartnett JJ, Nay WR (1975) Interpersonal attraction and help volunteering as a function of physical attractiveness. J Psychol 89:125–131

Nishio S, Ogawa K, Kanakogi Y et al (2012) Do Robot appearance and speech affect People’s attitude? Evaluation through the ultimatum game. In: IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN), Sep 9–13, Paris, pp 809–814

Nomura T, Suzuki T, Kanda T, Kato K (2006) Measurement of negative attitudes toward robots. Interact Stud Soc Behav Commun Biol Artif Syst 7:437–454

Nomura T, Kanda T, Suzuki T, Kato K (2008) Prediction of human behavior in human–robot interaction using psychological scales for anxiety and negative attitudes toward robots. IEEE Trans Robot 24:442–451

Robertson J (2010) Gendering humanoid robots: Robo-sexism in Japan. Body Soc 16:1–36

Siegel M, Breazeal C, Norton MI (2009) Persuasive robotics: the influence of robot gender on human behavior. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems IROS, NJ IEEE, St. Louis, MO Piscataway, pp 2563–2568

Suzuki T, Yamada S, Kanda T, Nomura T (2021a) Influence of social anxiety on people’s preferences for robots as daily life communication partners among young Japanese. Jpn Psychol Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12333

Suzuki T, Yamada S, Nomura T, Kanda T (2021b) Do people with high social anxiety prefer robots as exercise/Sports Partners? Jpn J Pers 30:42–44

Tay B, Jung Y, Park T (2014) When stereotypes meet robots: the double-edge sword of robot gender and personality in human–robot interaction. Comput Hum Behav 38:75–84

Walster E, Aronson V, Abrahams D, Rottman L (1966) Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 4:508–516

Weber J, Bath C (2007) “Social” robots & ‘emotional’ software agents: gendering processes and de-gendering strategies for ‘technologies in the making’. In: Zorn I, Maass S, Rommes E, Schirmer C, Schelhowe H (eds) Gender designs IT: construction and deconstruction of information society technology [in German]. Weissbaden, Germany Springer, pp 53–63

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 20H05573) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, T., Nomura, T. Gender preferences for robots and gender equality orientation in communication situations. AI & Soc 39, 739–748 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01438-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01438-7