Abstract

Purpose

To analyze whether sociodemographic characteristics influence the substance choice and preclinical and clinical course of suicidal poisoning.

Methods

This was a retrospective single-center study in patients hospitalized due to suicidal poisoning and who received at least one psychiatric exploration during their inpatient stay. Patients’ sociodemographic, anamnestic, preclinical, and clinical parameters were analyzed with respect to sex and age.

Results

1090 patients were included, 727 (67%) were females, median age was 39 years (min–max: 13–91) with 603 (55%) aged 18–44 years. 595 patients (54.8%) ingested a single substance for self-poisoning, 609 (59.5%) used their own long-term medication. Comparing to males, females preferred antidepressants (n = 223, 30.7%, vs n = 85, 23.4%; p = 0.013) and benzodiazepines (n = 202, 27.8%, vs n = 65, 17.9%; p < 0.001); males more often used cardiovascular drugs (n = 33, 9.1%, vs n = 34, 4.7%; p = 0.005) and carbon monoxide (n = 18, 5.0%, vs n = 2, 0.3%; p < 0.001). Use of Z-drugs (n = 1, 1.7%, to n = 37, 33.3%; p < 0.001) and benzodiazepines (n = 4, 6.9%, to n = 33, 29.7%; p = 0.003) increased with age (< 18 to > 64 years), while use of non-opioid analgesics (n = 23, 39.7%, to n = 20, 18.0%; p < 0.001) decreased. Average dose of substance in patients > 64 years was 12.9 ± 18.4 times higher than recommended maximum daily dose (compared to 8.7 ± 15.2 higher in those aged < 18 years; p < 0.001). Males more often required intensive care (n = 150, 41.3%, vs n = 205 females, 28.2%; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

These results underline the complexity of (para-)suicidal poisonings and identify potential measures for their prevention, such as restricting access and better oversight over the use of certain substances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Self-poisoning ranks second after hanging among the most frequently used suicide methods in Europe in terms of completed suicides [1, 2]. Among suicide attempts, deliberate self-poisoning represents the most frequent method [3, 4]. Recent analyses highlight an increasing frequency of self-poisoning in several countries, including Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, the United States, Australia, Brazil, Egypt, and Brazil [5,6,7,8,9,10,11] and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this trend [12,13,14,15]. Suicidal behavior varies with regard to socio-economic as well as cultural factors, but also according to different living circumstances and places of residence, and therefore partly shows considerable international and regional differences [16]. Hatzitolios described variations in substance choice in rural versus urban areas [17], however, our research group did not detect national preferences regarding the substances chosen in an earlier study [18]. In the same study, paracetamol ended up in fourth place among the most frequently used individual substances [18], while in other studies it was the most frequently used substance [19, 20]. Moreover, benzodiazepines, which are usually among the three most popular substances [19,20,21,22,23], ranked fourth among the used substance groups identified in our earlier survey [18]. These observed differences stress the need for the development of specific preventive measures, which take into consideration the individual, but also national or regional peculiarities.

Since many studies on suicides are carried out by psychiatric centres, the emphasis is often on psychiatric and not on somatic issues. In contrast, we focused our research on understanding the socio-demographic characteristics, preclinical factors, the clinical course and, in particular, toxicological aspects of self-poisoning. Exploration of these aspects of suicide is possible due to the structure of our department which encompasses the intensive care unit (ICU), internal medicine and toxicology. This ensures comprehensive patient follow up from presentation in the emergency room through (intensive) medical and specific toxicological therapy to discharge or onward transfer to psychiatry. The advantages of this unique research setting enabled us—after analyzing the characteristics and predictive factors of severe or fatal suicide outcome and the socio-demographic and psychiatric profile of patients hospitalized due to deliberate self-poisoning in previous publications [24, 25]—to address on the following questions in this paper: (i) do anamnestic or socio-demographic factors influence suicidal behavior, the (pre-)clinical course or substance choice in patients with intentional self-poisoning? (ii) do any sex- or age-group-specific characteristics exist with regard to substance choice or suicidal behavior?

Methods

Study design and setting

In this retrospective single-centre study, electronic records of patients treated in the Department of Clinical Toxicology at the Klinikum rechts der Isar of the Technical University of Munich, Germany. during the period from 01.01.2012 to 31.12.2016 were analyzed. Patients with self-poisoning based on suicide-related behavior (SRB), who attempted or completed suicide, and who were explored by a board-certified psychiatrist at least once during the inpatient stay in non-fatal cases were included in the study. SRB was defined as self-harm, suicide attempt and suicide, according to the definition of Silverman et al. [26]. (Para-)suicidal intent was diagnosed during the psychiatric consultation or assumed in case of fatal outcome, for example when a suicide note was found, or the relatives confirmed patient’s wish to die. Patient records were examined with regard to sociodemographic, anamnestic, preclinical and clinical parameters. A written informed consent was not obtained from patients due to the retrospective character of the study. The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the University Hospital (No. 270/16s), and it was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Patient data were extracted from the electronic medical records and transferred into a Microsoft Access database. In the analysis, only the demographic information from the initial SRB was considered for patients with multiple clinical admissions. Age-grouped analyses involved categorizing patients into four groups: <18 years, 18–44 years, 45–64 years, and > 64 years. Stratification of patients into four groups was further done according to the rescue time until hospital admission, with intervals defined as < 1 h, 1–3 h, 3–6 h, and > 6 h.

Information on the type and quantity of substances used was based on the information provided by the patient, information from outpatient services, details provided by companions, and results from toxicological analyses. In addition to the usual ingestion of medications, the recording encompassed other substances and non-pharmacological items, such as the ingestion of alkalis, batteries, paper clips or mushrooms for example or the inhalation of carbon monoxide for example. The ingested substances were systematically classified into various pharmacologically defined groups. Non-opioid analgesics included Ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, acetylsalicylic acid, acetaminophen, and metamizole, while the category “z-drug” comprised the medicines zolpidem and zopiclone. Illegal amphetamines, such as methylenedioxymethamphetamine and methamphetamine, were categorized as “illegal drugs”, while amphetamines prescribed for therapeutic purposes, such as methylphenidate, for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, were assigned to substance category “other drugs”. For each patient, up to eight substances were recorded, with each substance group documented only once per patient. Substance doses were reported by the patients themselves, by others, or estimated from empty packaging blisters. The aim was to obtain a uniform measure of overdoses of different substances, the multiple of the maximum daily dose (MMDD) for ingested substance was calculated based on an overdose or underdose of the substance-specific maximum daily dose (MDD). The determination of the MDD was based on the product information. The MDD used for the calculations are listed in Online Resource Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics (version 25, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R (version 3.5.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (± SD) and categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies. Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used for analysis of nominal and ordinal variables with the sample sizes of five or fewer; interval scaled variables were assessed by Student’s t-test. p-Values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant; because of the exploratory character of this study, we did not adjust for multiple testing.

Results

Out of 1287 cases of hospitalizations due to a suspected (para-)suicidal intoxication, 1140 had complete data (Online Resource Fig. 1). Among them, 50 cases of hospitalizations were a second or later admission in the same patient and were excluded. Therefore, 1090 patients were included in the final analysis; their characteristics are show in Tables 1 and 2.

Sociodemographic data

Patient characteristics according to sex and according to age group are shown in Tables 1 and 2, and Online Resource Table 2, respectively. Median age was 39 years (range 13, 91), 67% (n = 727) of the collective were female compared to 33% male patients (n = 363, Tables 1 and 2). The group of 18- to 44-year-olds was most frequently represented (n = 603; 55%), ahead of the 45- to 64-year-olds (n = 318; 29%) and the > 64-year-olds (n = 111; 10%, Tables 1 and 2). The smallest age group was the < 18-year-olds (n = 58; 5%). Overall, sexes were significantly differently distributed within the four age groups (p = 0.023, Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 1a). The relative proportion of females predominated in the two youngest age groups, while the relative proportion of males dominated in the 45–64 age group. The oldest group showed a balanced sex ratio in percentage terms. The age distribution without grouping was similar within the sex groups (p = 0.089, Table 1).

Statistically significant differences according to sex and to age were found with regard to family situation, occupational situation, living environment, and parenthood. Females were more often married or widowed, and more often lived with their family or partner (Table 1). The proportion of patients living alone increased with age (Table 2). Patients aged < 18 years or 18- to 44-year-olds mostly lived in communal living arrangements such as shared flats, assisted living or asylum seeker facilities, or lived with parents or relatives. Homelessness was only present in the middle age groups (18–44 and 45–64 years). Current occupation showed no significant differences within the sex groups (p = 0.754). Males were more frequently jobless (i.e. searching for job) than females (n = 72; 24%, vs n = 77; 13%, Table 1). The proportion of females predominated among pupils/students/trainees and those with no occupation. Occupation and family situation yielded age-typical results (Table 2). Almost half of females, and approximately two-thirds of patients in older age groups had children. Residence (size of the city, rural area) did not differ according to sex or age group (Tables 1 and 2). Majority of patients were German (n = 323, 65.1%); information on nationality was missing for 594 patients (Online Resource Table 2).

Anamnestic data

Overall, somatic pre-existing or concomitant cardiovascular, neurological and metabolic diseases were similarly frequent (13.5-13.7%, Online Resource Table 2). Substance abuse was self-reported by 45.5% of patients (Tables 3 and 4).

Males more often abused nicotine (p = 0.01) and alcohol (p = 0.004) than females (Table 3). Abuse of nicotine was lowest in patients aged > 64 years (13.5% vs. 30.5–32.3% in other age groups, p = 0.001), while patients aged 45–64 years more often abused alcohol (17% vs 0–9% in other age groups, p < 0.001, Table 4).

Used substances were predominantly patients´ own continuous medication (n = 609; 59.5%), followed by over-the-counter medicines (OTC), from the medicine cabinet (n = 138; 13.5%, Tables 3 and 4). Distribution of substance sources within the sex groups also showed significantly different results (p < 0.001, Table 3). The sex-specific difference was most remarkable for the substance source “no medication”, with a proportion of 16.9% (n = 56) for males versus 5.1% (n = 35) for females. The substance source “own medication” was most frequent within each age group and had the highest average age of 43.6 years (Table 4). A tendency towards the substance sources “relatives/friends”, “medicine chest/OTC” and “several sources” was shown within the youngest age group (Table 4).

While almost one third (n = 337; 31%) of patients stated a partnership conflict as a trigger for the current suicide(-attempt), almost the same number of patients (n = 338; 31%) could not name a trigger factor (Tables 3 and 4). Trigger factors were distributed significantly differently within the sex groups (p < 0.001, Table 3). While there were no significant sex-specific differences in the most frequent trigger factor “partner” or “no trigger”, males more frequently named the trigger factors “job”, “finances” and “justice”, while females stated preferentially the trigger factors “loss of a caregiver/pet” and “family problems”. The trigger factors were significantly differently distributed also within the age groups (p < 0.001, Table 4). Patients aged < 18 years frequently mentioned family problems, followed by problems in the social environment, while 18 to 44-year-olds frequently mentioned problems with their partner. Within the oldest group, health problems were most often mentioned, followed by conflict with partner, and the loss of a caregiver or a pet.

Preclinical and clinical data

In 69% of cases (n = 659), the rescue service was called by relatives or friends, and more than half of patients had a normal level of consciousness with a GCS of 15 when the ambulance arrived (Online Resource Table 2).

67% of patients (n = 735) were monitored and treated in the intermediate care unit (IMC) and 33% (n = 355) were admitted to the ICU. Almost 30% of patients stayed in hospital for < 24 h, a comparable percentage of 26% was treated in hospital for > 97 h (Online Resource Table 2). Males were more frequently treated in the ICU and females more frequently in the IMC (p < 0.001, Table 3). The necessity of intensive medical therapy increased with age (p = 0.025, Table 4).

9% of patients (n = 97) received gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal. This was administered by the ambulance service as well as in-hospital per os or via gastric tube after endotracheal intubation (Online Resource Table 2). 11% of cases (n = 121) required mechanical ventilation. 16% of patients (n = 178) were treated with an antidote (Online Resource Table 2). In addition to the classical antidotes such as flumazenil, naloxone or acetylcysteine, antidotes in the broader sense such as oxygen in the context of carbon monoxide poisoning, physostigmine in case of anticholinergic symptoms or magnesium in case of QTc time prolongation were administrated. Use of vitamin K or prothrombin concentrate in case of intoxication with anticoagulants, insulin-glucose in case of beta-blocker overdose, or ethanol therapy in case of ethylene glycol intoxication were also administered as antidote therapy.

Males had a higher rate of co-ingestion of alcohol during the SRB compared to females (35% vs 29%), although this difference was not significant (p = 0.053); co-ingestion of drugs occurred more than twice as often in males than in females (p = 0.026, Table 3). In case of co-ingestion of alcohol (p < 0.001) or drugs (p = 0.004), these substances differed according to age group (Table 4). Co-ingestion of alcohol was found most frequently in the two middle age groups, whereas co-ingestion of drugs was found only in the two youngest age groups.

Substance pattern

54.8% of patients (n = 595) took only one substance in the context of the suicide attempt (Online Resource Table 2). Mixed intoxications with two or three substances were documented in 22% (n = 239) and 12% (n = 133) of patients, respectively. Almost 95% of patients used up to three substances. In four cases (0.4%) the number of substances was unknown. On average, 1.9 substances (± 1.4) were used (one patient had a mixed intoxication with 13 single substances, Tables 3 and 4).

Females showed a non-significant tendency towards the use of a higher number of substances than males during suicide attempt (p = 0.087, Table 3); no age-group-specific differences in the number of substances used were noted (p = 0.109, Table 4).

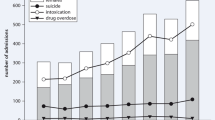

Antidepressants, benzodiazepines and non-opioid analgesics were chosen most frequently; medications from each of these substance classes were ingested with other agents in approximately two-thirds of cases (Fig. 1b, Online Resource Table 3). For both sexes, the same substance groups dominated, albeit with different preferences. When comparing the substances within the sex groups (Fig. 1c, Online Resource Table 3), it is noticeable that males significantly more often chose carbon monoxide (p < 0.001), insecticides (p = 0.017), cardiovascular drugs (p = 0.005), plants (nutmeg, castor bean or belladonna) (p = 0.045), anticoagulants (p = 0.008) and other sedatives (p = 0.045). Females preferred antidepressants (p = 0.013) and benzodiazepines (p < 0.001).

With regard the age group, an antibiotic use was documented in 5% and 3% within the two youngest age groups (< 18 and 18-44 years, respectively) while this substance class was not used by older patients (Fig. 1d, Online Resource Table 3). The highest rate of antihistamines and neuroleptics use was in the middle age groups. Use of cardiovascular drugs (p = 0.012), benzodiazepines (p = 0.003) and Z-drugs (p < 0.001) increased with age. The highest rate of drugs and narcotics was in those aged < 18 years at 12% (n = 7, p = 0.02). Non-opioid analgesics predominated within the two youngest age groups. No differences in opioids use between sex and age groups were observed.

Overall, the average MMDD was 8.7 ± 12.2, with no differences between the sexes (Table 3). However, the MMDD differed between the age-groups (p < 0.001) with a highest average value in patients aged > 64 years (12.9 ± 18.4) and lowest in those aged 18–44 years (7.3 ± 10.7, Table 4).

Discussion

The main findings of our study are that (i) there is an influence of sex on the frequency, mode, and severity of suicidal self-poisonings and (ii) age associates with the patterns of substance choice in suicidal self-poisonings. These findings may be useful for targeted programs of suicide prevention.

The average age of 40.5 years with a 1:2 male: female ratio in this work confirms the results of comparable studies [17, 20, 28, 29]. Similarly as in the UK study [30], the sex ratio converged in the older age groups. 34% of the cohort had a citizenship other than German. Compared to around 26% of the German population with a migration background or with 12% foreigners, the proportion in this study is significantly higher [31]. This may be due to a bias towards a major city in southern Germany with around 1.4 million inhabitants (the predominant enrollment area), with a higher proportion of non-German citizens.

Proportion of jobless patients was significantly higher than the average jobless rate in Germany in the study period (14% vs 6.7%) [32] thus supporting the notion that individuals searching for job are at a higher risk for (para-)suicidal behavior [33, 34].

As in comparable studies [35, 36], most patients presented to hospital within 3 h of substance use.

The substance pattern, with 55% of mono-intoxications and a preferred choice of antidepressants (17%), followed by benzodiazepines (15%) and non-opioid analgesics (15%), is similar to the results of recent studies [20, 37], in which antidepressants were used more frequently than benzodiazepines than in older studies [35, 38]. The tendency towards increased antidepressant vs benzodiazepines use in the context of (para-)suicidal poisoning has been observed in other studies, and it was associated with the increased frequency of antidepressant prescribing [39, 40]. This is supported by the fact that almost 60% of our patients ingested their own long-term medication. Analysis of substance choice revealed a sex-specific pattern with preference for antidepressants and benzodiazepines among females and use of carbon monoxide, chemicals, insecticides, drugs/intoxicants, anticoagulants, cardiovascular drugs, and other sedatives among males. The preferred choice of a pesticide/insecticide [27, 41] or gases, and chemicals [42] by males has already been described and was reconfirmed in this study, in which males were about three times more likely to use non-medical substances for SRB than females (17% vs 5%). Similar to the results reported here, Muheim et al. demonstrated that females more often chose non-opioid-analgesics and antidepressants, while males preferred sedatives. In contrast, a significantly increased use of opioids in males could not be confirmed in our work [43].

In terms of age-specific differences, younger patients tended to use antibiotics, antihistamines, drugs/narcotics, and non-opioid analgesics more frequently than older patients. Preferential use of non-opioid analgesics in the youngest patients was also found in a study by Froberg et al. [44] and could be due to a weaker intention to die, unawareness of the generally wider therapeutic range of this class of drugs (with the exception of acetaminophen), or ease of availability. The elderly were more likely to choose benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, anticoagulants, and cardiovascular drugs, i.e. long-term medications in this age group. Accordingly, we observed the highest frequency of own medication as a source in patients aged > 64 years. Of note, we did not observe differences in opioids use between the age groups, however, prior analysis found that individuals aged 45 to 54 years had a highest rates of suicide deaths with opioid poisoning in US [45].

9% of cases underwent therapeutic interventions, such as the administration of activated charcoal. In other studies, this frequency ranged from 1.5% to about two-thirds of patients [20, 46, 47]. This considerable variability may be a consequence of a limited preclinical availability of activated charcoal, variation in patient compliance, and a limited appropriate time window. Hemodialysis in 2% of cases and antidote therapy in 16% was comparable to a previous report (2% and 18%, respectively) [17].

In a study by Cook et al., the majority of patients were discharged within 24 h [20]. In our study, the length of inpatient stay was longer, as most patients stayed over 24 h. This may reflect a relatively high proportion of psychiatric follow-up therapy in this study, as a seamless transfer may result in a longer stay due to time bridging. Alternative explanation could be that our patients were more severely poisoned with 33% treated in the ICU compared to 1.5% in UK [20], 16% in Israel [28], and 11% in Greece [17]. The rate of ICU treatment in another German study was 61%, almost twice as high as in our study [19]. These different rates of ICU stays may be influenced by fluctuating ICU capacities or internal hospital monitoring strategies. For example, in most hospitals, many patients must be monitored in an ICU after a suicide attempt, even in mild poisoning cases, because adequate monitoring and self-protection cannot be guaranteed on a normal ward. Our department with an ICU and protected IMC, offers the possibility of a seamless “step-up/step-down concept”, which allows monitoring of severely poisoned patients in the ICU and less severe cases in the IMC, thus providing a better individualized monitoring of patients. Given the current shortage of intensive care beds, studies showed that from an internal medicine perspective, most self-poisonings can be adequately and sufficiently treated on an IMC or with supportive therapy by means of monitoring alone [20, 46, 48].

Co-ingestion of alcohol in about one in three patients is in line with the results of comparable studies [20, 38, 46]. Co-ingestion of alcohol predominated among males and in the two middle age groups, which corroborates the results of a similar study [42]. Also, a significantly more frequent co-ingestion of drugs was found in males. Regarding the age group-specific differences, co-ingestion of alcohol among adolescents (< 18 years) was significantly lower in this work (12%) than in a Finnish study, which detected alcohol in about half of the adolescents who committed suicide [49]. Thus, adolescents with a completed suicide appear to differ from the group of young people who attempted suicide in terms of co-ingestion of alcohol.

Alcohol and nicotine abuse predominated among males. Comparably, Mauri et al. found a significantly higher proportion of alcohol dependence (“alcoholism”) in males with (para-)suicidal intoxication [35]. According to a 2021 study, 17.6% of the German population had “harmful” alcohol consumption [50]. In contrast, only 9.3% of patients self-reported the alcohol abuse. Nicotine abuse in 30% of our cohort corresponded to the daily or occasional smoking behavior of 18- to 64-year-old German adults [50]. Illicit substance abuse (6.4%) was higher compared to the general German adult population (2.5%, [50]). However, above-average substance abuse rate is not surprising, as addictive disorders are associated with an increased risk of SRB [51]. The tendency of young males to abuse illicit substances more frequently [50] was hinted in this study (8% males versus 6% females), but without statistical significance.

Considering possible reasons for SRB, partner and family conflicts were common trigger factors, comparable to the findings of Hatzitolios et al. [17]. Males more often reported problems with job, finances, or law or justice as trigger factors, while females more often suffered from the loss of a caregiver or pet. This corresponds to the observations of a study from Hong Kong, which found a predominantly interpersonally triggered parasuicidal behavior in females compared to a personally triggered behavior in males [52]. Interestingly, there were no statistically significant differences in problems in relationship with partner between the sex groups in your study. In contrast, a Turkish study recorded relationship problems more frequently in female than in male suicides [53]. Furthermore, a study investigating psychosocial factors associated with suicidal thoughts in comparison to suicide attempts revealed that relational trauma was a significant risk factor distinguishing males from females [54]. Nevertheless, that study included not only subjects who attempted suicide but also those who reported suicidal ideations, and furthermore, did not distinguish between the means of suicide. In contrast, our study focused specifically on (para-)suicidal poisoning, which could potentially account for a lack relationship problems among triggers differentially reported by females and males. Furthermore, family problems and problems with the social environment were mentioned most frequently by the youngest patients and partner conflicts by those aged 18 to 44, while health problems and “loss of caregiver/pet” were predominantly documented for those aged ≥ 64 years. Similarly, loss of caregivers and associated isolation have been discussed as risk factors for suicide attempts in the elderly [55]. Finally, males had a significantly higher percentage of intensive care treatment. This could be explained by fact that, compared to females, males were more likely to develop a higher severity level of poisoning. In our prior analysis of the present cohort, we demonstrated a lower frequency of parasuicides in men, which is presumably associated with a stronger intention to die [25]. Furthermore, compared to females, males more often used non-medical substances which we found previously to predict severe or fatal course of suicide [24]. Higher lethality of suicidal behavior in males has been demonstrated in past studies not only by choice of method but also within the same method [56, 57].

Limitations

Our study has several limitations including the retrospective nature, the monocentric setting, and a suspected sampling bias. Patients aged < 18 years were the smallest age group because our center mainly treats adults and only in exceptional cases children. This could be perceived as a bias since distribution of patients into age groups was done according to clinical considerations, but not to ensure a uniform group size. Furthermore, most of patients came from the area of a major German city, which could not be representative for a broader population. Therefore, it can be supposed that frequency of singles living alone as well as use of drugs could be higher than in rural regions.

Since this was a single-center survey of a pre-selected patient population, it can be assumed that many intentional overdoses, also with (para-)suicidal intent, did not lead to a medical presentation due to a barely or slightly symptomatic course. For example, some patients reported having taken drugs in the past with suicidal intent but resuming their usual daily routine a few hours later after a symptom-free interval and without this incident being noticed by anyone. On the other side of the clinical spectrum, severely intoxicated persons who are found dead or do not reach a clinic alive are not included in this work. Overall, a certain selection bias of patients must be assumed.

Information on the ingested substances (in cases without toxicological analysis), trigger factors, and suicide circumstances was often based on incomplete information provided by the patients or obtained during external anamneses. In some cases, the information on the dose of the substances could only be estimated by the paramedics based on empty blisters or medicine boxes found in the rubbish bins. However, there remains considerable uncertainty as even in cases when date of purchase or dispensing was known, this was not necessarily the time of first substance use and thus could lead to dose underestimation. In contrast, in cases when empty blisters were found, it was assumed that all tablets were ingested which could lead to dose overestimation. In certain instances, an indication of quantity was only possible by means of the number of tablets taken without knowledge of the dosage of a drug. In these cases, the lowest commercially available dosage strength of a tablet was considered to estimate the minimum amount taken to ensure that an overdose actually occurred and not “just” several tablets of the lowest strength were taken within the MDD.

MDD was determined on the basis of the prescribing information, whereby a high MDD was presumed for the clear detection of actual intoxication. However, this procedure allows a certain degree of discretion on the part of those conducting the study. In addition, substances such as benzodiazepines or opioids are subject to a strong habituation effect, so that no standardized MDD can be determined.

Furthermore, as our survey was limited to the inpatient-somatic stay cases, a long-term follow-up of patients is lacking.

Finally, since the data collection was not hypothesis-driven, but it was rather aimed at capturing the interrelationships of a variety of parameters, random findings may have arisen due to multiple testing. Therefore, statistically significant results should be interpreted as trends until they will be validated in separate confirmatory studies.

Conclusions

The present study provides both a broad spectrum of descriptive data and a comprehensive presentation of person-, substance- and intoxication profiles of self-poisoning patients with SRB. The results of this work confirm known patterns and risk factors of SRB by intoxication and underline the complexity of (para-)suicidal behavior. Due to the multifactorial genesis of (para-)suicidal intoxications, there are many potential starting points for their prevention, such as restricting access to certain frequently used substances or also preclinically identifying particular at-risk groups and providing them in advance with appropriate preventive assistance measures.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Värnik A, van der Kõlves K, Marusic A, Oskarsson H, Palmer A, Reisch T, Scheerder G, Arensman E, Aromaa E (2008) Suicide methods in Europe: a gender-specific analysis of countries participating in the European alliance against depression. J Epidemiol Commun Health 62(6):545–551

Hegerl U, Wittenburg L (2009) Focus on mental health care reforms in Europe: the European alliance against depression: a multilevel approach to the prevention of suicidal behavior. Psychiatr Serv 60(5):596–599

Freeman A, Mergl R, Kohls E, Székely A, Gusmao R, Arensman E, Koburger N, Hegerl U, Rummel-Kluge C (2017) A cross-national study on gender differences in suicide intent. BMC Psychiatry 17(1):234

Czeizel AE (1994) Budapest registry of self-poisoned patients. Mutat Res/Environ Mutag Relat Subj 312(2):157–163

Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, Sivilotti ML, Hutson JR, Mamdani MM, Koren G, Juurlink DN (2015) Risk of suicide following deliberate self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry 72(6):570–575. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3188

Rheinheimer B, Kunz M, Nicolella A, Bastos T (2015) Trends in self-poisoning in children and adolescents in Southern Brazil between 2005 and 2013. Eur Psychiatry 30(S2):S136–S136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.09.266

Cairns R, Karanges EA, Wong A, Brown JA, Robinson J, Pearson SA, Dawson AH, Buckley NA (2019) Trends in self-poisoning and psychotropic drug use in people aged 5–19 years: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Australia. BMJ Open 9(2):e026001. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026001

Tyrrell EG, Orton E, Tata LJ (2016) Changes in poisonings among adolescents in the UK between 1992 and 2012: a population based cohort study. Inj Prev 22(6):400–406. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041901

Cutler GJ, Flood A, Dreyfus J, Ortega HW, Kharbanda AB (2015) Emergency department visits for self-inflicted injuries in adolescents. Pediatrics 136(1):28–34. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3573

Kasemy ZA, Sharif AF, Amin SA, Fayed MM, Desouky DE, Salama AA, Abo Shereda HM, Abdel-Aaty NB (2022) Trend and epidemiology of suicide attempts by self-poisoning among egyptians. PLoS ONE 17(6):e0270026. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270026

Paul E, Mergl R, Hegerl U (2017) Has information on suicide methods provided via the internet negatively impacted suicide rates? PLoS ONE 12(12):e0190136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190136

Elhawary AE, Lashin HI, Fnoon NF, Sagah GA (2023) Evaluation of the rate and pattern of suicide attempts and deaths by self-poisoning among egyptians before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Toxicol Res (Camb) 12(6):1113–1125. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxres/tfad103

Farah R, Rege SV, Cole RJ, Holstege CP (2023) Suspected suicide attempts by self-poisoning among persons aged 10–19 years during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States, 2020–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 72(16):426–430. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7216a3

Poonai N, Freedman SB, Newton AS, Sawyer S, Gaucher N, Ali S, Wright B, Miller MR, Mater A, Fitzpatrick E, Jabbour M, Zemek R, Eltorki M, Doan Q (2023) Emergency department visits and hospital admissions for suicidal ideation, self-poisoning and self-harm among adolescents in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. CMAJ 195(36):E1221–e1230. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.220507

Singh G, Hansen JP, Hulgaard D, Damkjær M, Christiansen E (2024) Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on self-poisoning behaviour with mild analgesics in Danish youth. Nord J Psychiatry 78(5):431–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2024.2339433

Bille-Brahe U, Andersen K, Wasserman D, Schmidtke A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, De Leo D, Haring C, Hawton K, Kerkhof A (1996) The WHO-EURO multicentre study: risk of parasuicide and the comparability of the areas under study. Crisis 17(1):32–42

Hatzitolios AI, Sion ML, Eleftheriadis NP, Toulis E, Efstratiadis G, Vartzopoulos D, Ziakas AG (2001) Parasuicidal poisoning treated in a Greek medical ward: epidemiology and clinical experience. Hum Exp Toxicol 20(12):611–617. https://doi.org/10.1191/096032701718890595

Geith S, Didden C, Rabe C, Zellner T, Ott A, Eyer F (2022) Lessons to be learned: identifying high-risk medication and circumstances in patients at risk for suicidal self-poisoning. Int J Ment Health Syst 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00513-8

Sorge M, Weidhase L, Bernhard M, Gries A, Petros S (2015) Self-poisoning in the acute care medicine 2005–2012. Anaesthesist 64(6):456–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00101-015-0030-x

Cook R, Allcock R, Johnston M (2008) Self-poisoning: current trends and practice in a U.K. teaching hospital. Clin Med (Lond) 8(1):37–40. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.8-1-37

Ghazinour M, Emami H, Richter J, Abdollahi M, Pazhumand A (2009) Age and gender differences in the use of various poisoning methods for deliberate parasuicide cases admitted to loghman hospital in Tehran (2000–2004). Suicide Life Threat Behav 39(2):231–239. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2009.39.2.231

Bilen K, Ottosson C, Castren M, Ponzer S, Ursing C, Ranta P, Ekdahl K, Pettersson H (2011) Deliberate self-harm patients in the emergency department: factors associated with repeated self-harm among 1524 patients. Emerg Med J 28(12):1019–1025. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2010.102616

Salles J, Calonge J, Franchitto N, Bougon E, Schmitt L (2018) Factors associated with hospitalization after self-poisoning in France: special focus on the impact of alcohol use disorder. BMC Psychiatry 18(1):287. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1854-0

Geith S, Lumpe M, Schurr J, Rabe C, Ott A, Zellner T, Rentrop M, Eyer F (2022) Characteristics and predictive factors of severe or fatal suicide outcome in patients hospitalized due to deliberate self-poisoning. PLoS ONE 17(11):e0276000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276000

Lumpe M, Schurr J, Rabe C, Ott A, Zellner T, Rentrop M, Eyer F, Geith S (2022) Socio-demographic and psychiatric profile of patients hospitalized due to self-poisoning with suicidal intention. Ann Gen Psychiatry 21(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-022-00393-3

Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O’Carroll PW, Joiner TE (2007) Rebuilding the tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 1: background, rationale, and methodology. Suicide Life Threat Behav 37(3):248–263. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.248

Kim B, Ahn JH, Cha B, Chung YC, Ha TH, Hong Jeong S, Jung HY, Ju G, Kim EY, Kim JM, Kim MD, Kim MH, Kim SI, Lee KU, Lee SH, Lee SJ, Lee YJ, Moon E, Ahn YM (2015) Characteristics of methods of suicide attempts in Korea: Korea National suicide Survey (KNSS). J Affect Disord 188:218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.050

Novack V, Jotkowitz A, Delgado J, Novack L, Elbaz G, Shleyfer E, Barski L, Porath A (2006) General characteristics of hospitalized patients after deliberate self-poisoning and risk factors for intensive care admission. Eur J Intern Med 17(7):485–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2006.02.029

Kim J, Kim M, Kim YR, Choi KH, Lee KU (2015) High prevalence of psychotropics overdose among suicide attempters in Korea. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 13(3):302–307. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2015.13.3.302

Prescott K, Stratton R, Freyer A, Hall I, Le Jeune I (2009) Detailed analyses of self-poisoning episodes presenting to a large regional teaching hospital in the UK. Br J Clin Pharmacol 68(2):260–268

bpb (2020) Bundeszentrale fuer politische Bildung. Lizenz: cc by-nc-nd/30/de

RKI (2015) Robert Koch-Institut, Gesundheit in Deutschland. Gesundheitsberichtserstattung des Bundes. https://doi.org/10.17886/rkipubl-2015-003. ISBN 978-3-89606-225-3

Platt S, Kreitman N (1985) Parasuicide and unemployment among men in Edinburgh 1968–82. Psychol Med 15(1):113–123

Nordt C, Warnke I, Seifritz E, Kawohl W (2015) Modelling suicide and unemployment: a longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000-11. Lancet Psychiatry 2(3):239–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(14)00118-7

Mauri MC, Cerveri G, Volonteri LS, Fiorentini A, Colasanti A, Manfre S, Borghini R, Pannacciulli E (2005) Parasuicide and drug self-poisoning: analysis of the epidemiological and clinical variables of the patients admitted to the Poisoning Treatment Centre (CAV), Niguarda General Hospital, Milan Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health (CP EMH) 1(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-1-5

Kara H, Bayir A, Degirmenci S, Kayis SA, Akinci M, Ak A, Agacayak A, Azap M (2014) Causes of poisoning in patients evaluated in a hospital emergency department in Konya, Turkey. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc 64(9):1042–1048

Mikhail A, Tanoli O, Legare G, Dube PA, Habel Y, Lesage A, Low NCP, Lamarre S, Singh S, Rahme E (2018) Over-the-counter drugs and other substances used in attempted suicide presented to emergency departments in Montreal. Crisis, Canada. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000545

McGrath J (1989) A survey of deliberate self-poisoning. Med J Aust 150(6):317–324

Buckley NA, Whyte IM, Dawson AH, McManus PR, Ferguson NW (1995) Self-poisoning in Newcastle, 1987‐1992. Med J Aust 162(4):190–193

Kelly C, Weir J, Rafferty T, Galloway R (2000) Deliberate self-poisoning presenting at a rural hospital in Northern Ireland 1976–1996: relationship to prescribing. Eur Psychiatry 15(6):348–353

Noghrehchi F, Dawson AH, Raubenheimer JE, Buckley NA (2021) Role of age-sex as underlying risk factors for death in acute pesticide self-poisoning: a prospective cohort study. Clin Toxicol 60(2):184–190

Vancayseele N, Portzky G, van Heeringen K (2016) Increase in self-injury as a method of self-harm in Ghent, Belgium: 1987–2013. PLoS ONE 11(6):e0156711

Muheim F, Eichhorn M, Berger P, Czernin S, Stoppe G, Keck M, Riecher-Rössler A (2013) Suicide attempts in the county of Basel: results from the WHO/EURO multicentre study on suicidal behaviour. Swiss Med Wkly 143:w13759

Froberg BA, Morton SJ, Mowry JB, Rusyniak DE (2019) Temporal and geospatial trends of adolescent intentional overdoses with suspected suicidal intent reported to a state poison control center. Clin Toxicol 57(9):798–805

Braden JB, Edlund MJ, Sullivan MD (2017) Suicide deaths with opioid poisoning in the United States: 1999–2014. Am J Public Health 107(3):421–426. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2016.303591

Hendrix L, Verelst S, Desruelles D, Gillet J-B (2013) Deliberate self-poisoning: characteristics of patients and impact on the emergency department of a large university hospital. Emerg Med J 30(1):e9

Hall A, Curry C (1994) Changing epidemiology and management of deliberate self poisoning in Christchurch. N Z Med J 107(987):396–399

Schwake L, Wollenschläger I, Stremmel W, Encke J (2009) Adverse drug reactions and deliberate self-poisoning as cause of admission to the intensive care unit: a 1-year prospective observational cohort study. Intensive Care Med 35(2):266–274

Lahti A, Harju A, Hakko H, Riala K, Rasanen P (2014) Suicide in children and young adolescents: a 25-year database on suicides from Northern Finland. J Psychiatr Res 58:123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.020

Rauschert C, Möckl J, Seitz NN, Wilms N, Olderbak S, Kraus L (2022) The Use of Psychoactive substances in Germany: findings from the epidemiological survey of substance abuse 2021. Dtsch Arztebl Int 119(31–32):527–534. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0244

Gvion Y, Levi-Belz Y (2018) Serious suicide attempts: systematic review of psychological risk factors. Front Psychiatry 9:56. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00056

Pan PC, Lieh-Mak F (1989) A comparison between male and female parasuicides in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 24(5):253–257

Oner S, Yenilmez C, Ozdamar K (2015) Sex-related differences in methods of and reasons for suicide in Turkey between 1990 and 2010. J Int Med Res 43(4):483–493

Richardson C, Robb KA, McManus S, O’Connor RC (2023) Psychosocial factors that distinguish between men and women who have suicidal thoughts and attempt suicide: findings from a national probability sample of adults. Psychol Med 53(7):3133–3141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721005195

Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, Kopp A, Redelmeier DA (2004) Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 164(11):1179–1184

Mergl R, Koburger N, Heinrichs K, Székely A, Tóth MD, Coyne J, Quintão S, Arensman E, Coffey C, Maxwell M (2015) What are reasons for the large gender differences in the lethality of suicidal acts? An epidemiological analysis in four European countries. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0129062

Cibis A, Mergl R, Bramesfeld A, Althaus D, Niklewski G, Schmidtke A, Hegerl U (2012) Preference of lethal methods is not the only cause for higher suicide rates in males. J Affect Disord 136(1–2):9–16

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG initiated the study, performed data entry, and wrote the manuscript. AO performed the statistical analysis of the data. ML, JS, and CR contributed with analysis and interpretation of data and revising the article of important intellectual content. SS, RS, MR, and TZ and FE made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data and manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geith, S., Lumpe, M., Schurr, J. et al. Clinical course and demographic insights into suicide by self-poisoning: patterns of substance use and socio-economic factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02750-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02750-x