Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic led to concerns about increases in suicidal behaviour. Research indicates that certain types of media coverage of suicide may help reduce suicidality (the Papageno effect), while other types may increase suicidality (the Werther effect). This study aimed to examine the tone and content of Canadian news articles about suicide during the first year of the pandemic.

Methods

Articles about suicide from Canadian news sources were collected and coded for adherence to responsible reporting of suicide guidelines. Articles which directly discussed suicidal behaviour in the COVID-19 context were identified and compared to other suicide articles in the same period. Lastly, a thematic analysis was conducted on the sub-sample of articles discussing suicide in the COVID-19 context.

Results

The sub-set of articles about suicide in the COVID-19 context (n = 103) contained significantly more putatively helpful content compared to non-COVID-19 articles (n = 457), such as including help information (56.3% Vs 23.6%), quoting an expert (68.0% Vs 16.8%) and educating about suicide (73.8% Vs 24.9%). This lower adherence among non-COVID-19 articles is concerning as they comprised over 80% of the sample. On the plus side, fewer than 10% of all articles provided monocausal, glamourized or sensational accounts of suicide. Qualitative analysis revealed the following three themes: (i) describing the epidemiology of suicidal behaviour; (ii) discussing self and communal care; and (iii) bringing attention to gaps in mental health care.

Conclusion

Media articles about suicide during the first year of the pandemic showed partial adherence to responsible reporting of suicide guidelines, with room for improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research suggests that certain types of media coverage of suicide can influence suicidal behaviour in the population [1, 2]. On the one hand, the Werther effect is a well-documented phenomenon describing a rise in suicides following extensive, repeated, and sensational news media coverage of suicide, particularly when reports focus on celebrity suicides, describe any suicide method in detail and present expert opinion and/or epidemiological facts in an alarming manner, devoid of discussion about suicide prevention [3,4,5,6]. It is hypothesized that this rise in suicides is facilitated through modelling and social learning, whereby vulnerable people learn to identify with the deceased by exposure to media coverage that implies that suicide is a common and acceptable solution to ongoing struggles, or even a heroic act worthy of emulation [4].

On the other hand, the media can be a vehicle for increased education, for example raising awareness that suicide is preventable, pointing to available suicide prevention and mental health care resources; as well as highlighting stories of hope and recovery through presentation of individual stories, or marshalling statistics and expert opinion focused on suicide prevention [3, 7,8,9,10]. Consumers of such media pieces may learn that helpful service-utilization, mental health recovery progress and mastery of crises are common processes among suicidal individuals, thus modelling such beneficial phenomena [3]. Indeed, such types of coverage can lead to a reduction in suicides, and is known as the Papageno effect.

Rates of suicide are influenced by a multiplicity of complex factors [11]. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic represents a period of potential concern for suicidal behaviour given reported increases in isolation, unemployment, domestic violence and other risk factors for suicide and adverse mental health [12]. As such, the importance of renewed suicide prevention efforts and other protective measures was emphasized at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic [12, 13]. Responsible reporting on suicide is one such protective measure that has been emphasized in Canada and beyond throughout the months of the pandemic [13,14,15].

Of note, various national and international organizations have developed responsible reporting of suicide recommendations which aim to diminish content associated with the Werther effect, while sometimes promoting the inclusion of putatively helpful content to foster help-seeking, suicide prevention and the Papageno effect [16,17,18,19,20]. These have been complemented by new specific recommendations from suicide experts related to reporting suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as avoiding broad claims about the inevitability of suicide, as well as pointing to available resources and self-care strategies appropriate to the COVID-19 context [15].

A few studies have sought to assess news media coverage of suicide during the pandemic, but these have some limitations. For example, one UK study focused exclusively on reports of suicide deaths and attempts in the first four months of the pandemic [21], while another US study focused on a specific high-profile death of a New York physician [22]. To our knowledge, there has been a lack of research taking a broad-brush approach to suicide coverage over a longer period during the pandemic.

As such, this study aims to fill this gap by examining the tone and content of suicide reporting in Canada over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary objective was to assess articles’ adherence to responsible reporting of suicide guidelines, especially content putatively associated with a Werther effect. A secondary objective was to compare guideline adherence between articles directly focused on COVID-19 with articles not focused on COVID-19. A third objectivewa to identify prominent themes and narratives occurring in the subsample of articles focused on COVID-19 and suicide.

Methods

News media articles published over a 1-year period (1 March 2020–28 February 2021) were collected on a monthly basis using Factiva, an online database containing media articles from a wide variety of Canadian news sources. This 1-year period was chosen as lockdowns, social distancing and other public health measures were implemented across Canada in March 2020.

Articles containing the keyword “suicide” were searched in over 40 top news sources, including three national newspapers (e.g. National Post), six online-only news websites (e.g. CBC News), and 38 high-circulation metropolitan or regional newspapers (e.g. Toronto Star). Those which mentioned suicide in passing or as a metaphor (e.g., “political suicide”) were excluded, as well as those which focused on suicide-bombing or assisted suicide/euthanasia. Duplicate articles (e.g., identical articles in the same news source) were omitted, however re-published articles (e.g., identical articles published across multiple different news sources) were included, given the relevance of considering frequency of coverage in studies of contagion [1, 3].

This study builds upon an ongoing media monitoring study of suicide in the Canadian news media, for which a more detailed description of the methods is published elsewhere [23]. In sum, articles were coded for adherence to suicide reporting recommendations, primarily examining putatively harmful content that has been associated with a Werther effect, while secondarily examining putatively helpful content that could be associated with a Papageno effect. These recommendations were selected based on the existing literature about the Werther effect and the Papageno effect [1, 3, 5, 10] and drew from existing guidelines relevant to the Canadian context [16, 18, 19], but were mainly based on Mindset guidelines [19], which have been used in several previous studies [8, 9, 23].

The Mindset guidelines were sponsored by the Mental Health Commission of Canada to encourage the responsible reporting of mental health and suicide and are available on a devoted website and as a short booklet, with over 5,000 distributed to journalists across Canada [23]. Mindset includes a series of bullet points related to writing about suicide that predominantly attempt to guide the journalist to avoid coverage that could lead to a Werther effect, for example “do not go into details about the method used” and “don’t romanticize the act…”.

A few bullet points focus on content that might putatively foster a Papageno effect, for example, “do tell others considering suicide how they can get help”. However the Mindset guidelines do not include explicit bullet-points advising journalists to cover hopeful narratives of resilience, survival stories and mastery of crises, which are arguably the most important stories for suicide prevention and are instrumental in fostering a Papageno effect [3, 5,6,7]. We selected 11 variables based on these guidelines that have been used in previous studies, thus providing a basis for temporal comparison [8, 9, 23]. These consist of the following:

-

1.

The headline includes the word “suicide” or a synonym, for example, “shot himself” (yes/no).

-

2.

The article mentions the suicide method used (yes- alludes to method, e.g., asphyxiation; yes: a passing mention, e.g., hanging; yes- detailed description; no).

-

3.

The article mentions the suicide location (yes/no).

-

4.

The article gives a monocausal explanation of suicide (yes/no).

-

5.

The article glamourizes/romanticizes the death, e.g., describing it as “heroic” (yes/no).

-

6.

The article includes sensational language, for example, “suicide hotspot” (yes/no).

-

7.

The article uses discouraged words/phrases, for example, “committed” suicide (yes/no).

-

8.

The article provides help-seeking information, for example, a helpline number (yes/no).

-

9.

The article includes a quote by a suicide expert (yes/no).

-

10.

The article includes a quote by the suicide bereaved (yes/no).

-

11.

The article tries to educate the public about suicide (yes/no).

Variables 1–7 aim to reduce putatively harmful content associated with a Werther effect, whereas variables 8, 9 and 11 have the potential to encourage putatively protective content, especially when focused on suicide prevention and treatments. Some guidelines suggest caution in presenting quotes by the bereaved, making this a more ambiguous variable [17, 18].

Each article was coded for further content characteristics, such as (i) the focus of the piece (e.g., suicide death/attempt, event/policy/research related to suicide); (ii) the suicide discussed (e.g., local individual/community member, high-profile person); (iii) demographic information (e.g., age/gender if applicable); and (iv) other general article characteristics (e.g., word count, date of publication).

An additional binary code was added to bifurcate articles into those either (i) directly focused on suicide in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; or (ii) focused/ discussed suicide independent of the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this bifurcation, all suicide articles were searched for the following key words: pandemic, coronavirus, COVID, COVID-19, virus and/or lockdown for further screening. Articles which directly discussed COVID-19 in relation to suicidal behaviour were put into category one, whereas those which were not related to COVID-19 or mentioned COVID-19 in passing (e.g., suicide inquest delayed due to COVID) were put into category two.

All articles were retrieved and coded by the second author, with ongoing training and regular supervision by the first author, who is the principal investigator of an ongoing media monitoring study of suicide [8, 9, 23] As part of this ongoing media monitoring study, the authors have been involved in several double-coding exercises of sub-sets of news media articles about suicide using the questions listed above. These inter-rater reliability exercises led to an average k score of 0.83 (range 0.55–1.0) with perfect agreement on 6 variables, in a test of 20 different articles [23] Codes for each article were stored in Excel, then imported into R statistical software [24] at the end of the study period to calculate frequency counts, proportions, and statistical comparisons.

Finally, an inductive thematic content analysis was conducted by the second author, again with supervision and training by the first author, to identify common themes, narratives and content in the sub-sample of articles about COVID-19 and suicide. Including an inductive sub-analysis is recommended practice in order to complement the rigid framework of using pre-defined quantitative codes [25]. The analysis followed standard procedure [26, 27], namely the following: (i) immersion in the dataset through reading and re-reading the sub-sample of articles; (ii) creating a list of specific themes or ‘open codes’ which appear across articles; (iii) comparing and collapsing of overlapping codes; and (iv) a final round of focused coding where finalized codes are applied and enumerated across the sub-sample.

Results

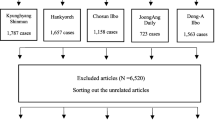

A total of 4,461 articles were retrieved over the 1-year period. 3,901 were excluded because they (i) mentioned suicide only in passing; (ii) used suicide metaphorically, for example, “political suicide,”; (iii) focused upon suicide-bombing; (iv) focused on euthanasia; or (v) were exact duplicates of a previous version in the same news source. This resulted in a final sample of 560 articles. Among these, 103 articles (18%) focused on COVID-19 and suicide, while 457 articles (82%) reported suicide independent of the COVID-19 situation.

Quantitative results

General article characteristics are presented in Table 1. In terms of article focus, 74.8% (n = 77) of COVID articles reported on events, policy or research related to suicide, with less than a quarter (n = 25, 24.3%) reporting on a suicide death/attempt. In contrast, non-COVID articles reported on a death/attempt in nearly 60% of cases (n = 272, 59.5%), with only a third focusing on events, policy or research (n = 151, 33.0%). In other words, COVID articles were over twice as likely to focus on events, policy and research than non-COVID articles.

Variables related to suicide reporting recommendations are presented in Table 2. Overall, articles showed high adherence to certain guidelines, and low adherence to other guidelines. For instance, fewer than 10% of articles provided a monocausal (n = 39, 7.0%), glamourized (n = 31, 5.5%), or sensational (n = 47, 8.4%) account of suicide, however only around 1 in 3 articles attempted to educate about suicide (n = 190, 33.9%) or provide help-seeking information (n = 166, 29.6%). Only partial adherence was observed in other key variables, for example the suicide location was mentioned in 27% of articles (n = 151) and the method in 31.8% (n = 178). Comparing COVID and non-COVID articles, the chi-squared calculations showed significant differences for 4 of the 11 variables, with COVID related articles showing greater adherence on all 4 significant variables. For one, the COVID articles rarely included details about any method (n = 5, 4.9%), in contrast to the non-COVID articles which included details in over 10% of cases (n = 57, 12.5%). Interestingly, the COVID subsample showed significantly higher adherence to the guidelines related to putatively helpful content. Of note, over half included help information (n = 58, 56.3%), in contrast to 23.6% (n = 108) for general suicide articles. Further, nearly 70% of COVID articles quoted an expert (n = 70, 68.0%) and attempted to educate about suicide (n = 76, 73.8%), in contrast to 16.8% (n = 77) and 24.9% (n = 114), respectively, for non-COVID articles.

Prior research on media reporting of suicide and mental illness indicates that articles about events, policy and research, as well as articles not focused on individuals, tend to be reported more positively [23, 28]. Given the high proportion of these articles in the COVID subsample, a stratified analysis within the COVID-19 sub-sample was conducted to compare guideline adherence between the following two types of articles (i) those focused on suicide incidents (deaths and attempts combined); and (ii) those focused on events, policy and /or research articles.

As seen in Table 3, adherence to guidelines was generally higher for event, policy and research articles than for suicide incident reports, both for avoiding potentially harmful elements and actively including helpful content. Interestingly, the stratified analysis revealed that the event, policy and research articles related to suicide and COVID-19 had significantly higher proportions of positive elements, such as helpline information (n = 47, 61.0%), expert quotes (n = 67, 87.0%), and educative content (n = 68, 88.3%) about suicide, compared to the non-COVID reports. Likewise, for suicide incidents, COVID articles contained significantly higher proportions of educative content (n = 8, 32.0%) compared to non-COVID articles (n = 29, 10.7%).

Qualitative results

The qualitative analysis focused on the 103 COVID-related articles. Thirty-three of these were re-published content (identical articles appearing in more than one different news source). Since there was no added benefit to analysing multiple copies of these articles, each article was included only once, resulting in a total of 70 unique articles (listed in Appendix 1).

The qualitative analysis revealed the following three key themes in the articles reporting suicide in the context of COVID-19: (i) describing the epidemiology of suicidal behaviour; (ii) discussing self-care and communal care; and (iii) bringing attention to gaps in mental health care (see Table 4).

Epidemiology of suicidal behaviour

First, one of the most prominent themes across the articles was an epidemiological discussion of suicidal behaviour during the pandemic, appearing in 64% (n = 45) of articles. Articles reported on the prevalence of suicidal ideation, deaths, and attempts during the pandemic, citing survey results, ongoing research findings, as well as data from crisis centres. For instance, one article from December 2020 reported that “one in 10 Canadians have been experiencing recent thoughts or feelings of suicide up from 6% in the spring and 2.5% throughout pre-pandemic 2016” (A48). Others focused on data from distress lines, such as reporting on an increase in the number and intensity of suicide-related calls.

Articles also speculated on the longer-term impacts of the pandemic on suicides, generally taking a cautious and balanced approach to reporting. For instance, articles typically included expert consultation to interpret research results, and made careful counterpoints about the certainty of these trends. For instance, one article reported rising suicidal thinking with key caveats:

"It can take years for Canada to collect and release suicide statistics, making it impossible to know whether the pandemic is associated already with an increase in fatal self-harm. Juveria Zaheer, a psychiatrist and suicide researcher at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, said this was a key question, but that the answer is likely to be complicated. She noted the many factors that can influence a suicide trend, and warned of the harm that could be created by telling the public that a rise is to be expected. "If we're telling a story that there's an inevitability to an increased rate of suicide, that could send the message that there isn't hope or that there aren't services available," (A46)

However, even when reporting on epidemiological research, around 20% of articles engaged in speculation which took a more sensational and scaremongering tone. For example, one article, which was re-published across nine major metropolitan newspapers, predicted that “Unemployment brought on by the COVID-19 lockdown could trigger as many as 2100 extra suicides this year and next… based on historic evidence that each one per cent rise in joblessness is associated with a similar one per cent hike in the number of people who die by suicide” (A20). Indeed, several headlines use language such as the pandemic ‘fuelling’ suicide rates (A6), causing a ‘spike’ in suicides or suicide-related calls (A13, A21, A24), or ‘triggering’ extra suicides (A20). Interestingly, such headlines were typically more sensational than the body of the article, which included a more in-depth and nuanced exploration of suicide trends.

Self-care and communal care

Another major theme appearing in 64% (n = 45) of the articles was self-care and communal care. Articles often emphasized that “help is available” (A32, A52, A55, A62) and to “reach out” if you or someone you know is struggling (A8, A29, A30, A34, A35, A43, A49). This often took the form of a list of resources at the end of the article, such as help-line numbers and websites. However, many articles also went into further detail about what individuals can do in terms of self-care, often soliciting the advice of experts in the fields of mental health and suicide. For example, one article states that it is “all of our responsibility to look out for one another”, quoting a branch representative from the Canadian Mental Health Association:

“If you know someone that struggles, just check in with them. If you have a feeling in your gut about someone or see them express hopelessness, just have an honest conversation with them … People sometimes wonder if asking someone if they’ve contemplated suicide will put the idea in their head. That’s not true–it will actually provide relief”. (A31)

Articles also emphasized the importance of maintaining general mental well-being during the pandemic, for example, by advising readers to stay connected with one another (A5, A46), to spend time outdoors (A15, A31), and to engage in meaningful activities (A8). Indeed, one article notes, “there are also protective factors that reduce the risk of mental anguish and suicide–meaning, purpose, hope and belonging – and people can work to increase those’. (A43).

Bringing attention to gaps in mental health system

Finally, another theme present in 50% (n = 35) of articles was bringing attention to gaps in the mental health system, with suicide often related to such gaps. For example, several articles described how the pandemic heightened the demand for mental health support, while also shutting down many services due to public health restrictions. However, these articles described this as an ongoing phenomenon because of an “ill-prepared” and “under-resourced” system (A14), which was already “not meeting people’s needs due to long waitlists, access issues, inequity and underfunding” (A48).

This theme is especially salient in certain articles reporting on suicide deaths. For example, one article highlights the gaps faced by people with mental illness: “For him, the COVID-19 pandemic—with its broad shutdowns and cancellations of crucial counselling services—didn't cause his wife's death, but it exposed long-standing weaknesses in a system that failed her” (A36). Likewise, another report following a suicide cluster in an Indigenous community states that “the challenges faced by northern communities in accessing mental health services are not new, but leaders say that the pandemic has brought them back to the surface” (A18).

Overall, many articles call for longer-term planning for suicide prevention, citing the pandemic as an important warning sign to increase resources and funding for mental health services. For example, one article about rising suicidal ideation concludes that “more needs to be done to overhaul the Canadian mental health system in the long run”—one that draws from data in the pandemic to be “more effective and more aligned with what people need" (A50).

Discussion

The results from this study indicate partial adherence to responsible reporting of suicide guidelines, with room for improvement in many key areas such as the following:(i) including more putatively helpful content such as help seeking information, which was only present in around 1 in 3 articles; (ii) focusing discussion on prevention and treatments, rather than decontextualized presentation of survey results and speculative projection of future trends; and (iii) omitting information related to method and location, which was present in a substantial minority of articles. Of note, articles about COVID-19 included significantly more putatively helpful elements, such as educating about suicide and help resources compared to non-COVID-19 articles. However, these COVID-19 articles comprised less than 20% of the media articles in the sample, meaning routine everyday reporting of suicide remained suboptimal during the pandemic.

The qualitative analysis indicates that articles about COVID-19 and suicide often attempted to discuss epidemiological trends in a balanced manner, but sometimes discussed rising suicidality and speculated about future trends in an alarming fashion, without any content related to prevention or treatments. This has been linked to a Werther effect in previous studies [3]. That said, many articles included helpful information such as self-care advice or a list of suicide prevention resources, using the pandemic situation as a platform to discuss broader issues related to suicide, such as issues in mental health care. These elements align with specific COVID-19 responsible reporting of suicide recommendations written at the start of the pandemic, such as avoiding broad claims about the inevitability of suicide, pointing to available resources and promoting self-care [12,13,14,15].

Of note, a similar study using the same research design examined media coverage of suicide in Canada in the 12 months (2019–2020) before the pandemic [23] allowing for comparison of trends. Adherence to most guidelines remained stable, with some showing improvement in the pandemic year. For instance, articles including sensational language and those describing the location showed large decreases. There was also an increase in the proportion of articles which included help information, expert quotes, and educating about suicide, which is likely attributable to the COVID-19 articles. In terms of the suicide discussed, most categories appeared in similar proportions (e.g., local person, Indigenous); however, there were notably fewer articles about high-profile suicides and murder-suicides in the current study period.

There are several possible interpretations to the improved coverage, especially among articles related to COVID-19. For one, the COVID-19 situation may have increased awareness of suicide as an issue among Canadian journalists, leading them to better utilize responsible reporting of suicide recommendations [11, 15]. Another explanation is that this continues a long-term trend of improved reporting of suicide and mental health issues in recent years [29, 30].

All this raises the following question: could the observed coverage contribute to any effect on actual suicide rates in Canada during the pandemic? One study found that suicides in Canada decreased from 10.1 deaths per 100,000 in the year before the pandemic (March 2019—February 2020) to 7.3 per 100,000 in the first year of the pandemic (March 2020—February 2021: the exact same time period of the present study), meaning an absolute difference of 1300 deaths [31].These findings converge with a cross-national interrupted time-series analysis, indicating a similar decrease in suicide rates during the first year of the pandemic in the vast majority of Western countries studied, including the USA, England, Australia, and New Zealand [32, 33]. These studies also indicated declining rates in several Canadian provinces included in the analysis, such as British Columbia, Manitoba and Alberta.

Such a decrease was likely caused by a variety of intersecting factors including (i) governmental financial support to citizens negatively affected by COVID-19; (ii) the widespread provision of free or low-cost mental health supports and resources such as crises lines and therapeutic counselling; (iii) concerted action to raise awareness about effective self-care and mental health resilience strategies by community mental health organizations; (iv) heightened social capital and community spirit in the face of a common threat; and (v) the psychosocial benefits of working from home; including more time with family, less time commuting and fewer work-related stressors [31,32,33].

It is possible that the improved media coverage and partial adherence to responsible reporting of suicide guidelines observed in the present study may have interacted with the above-described factors to contribute in some manner to the observed decrease in Canadian suicides. However, the data (and study design) used in the present study do not allow for any such causal claims, and further experimental and epidemiological research is necessary to examine the relationship between media coverage and any possible Papageno effect.

This study has some limitations. First, we only searched articles for the keyword “suicide”, meaning that we may have missed articles using other terms such as “took their own life”. Second, our focus on high-circulation Canadian newspapers left out other mainstream media such as television and radio, which may have shown other patterns of reporting. Third, there was a large difference in the number of articles about COVID, (n = 103) compared to non-COVID articles (n = 457). Such a magnitude of difference in cell sizes can contribute to a lower statistical power to detect true differences for some variables in Table 2. Fourth, we did not consider “new media” content such as social or alternative media, which would be needed for a more complete picture of suicide reporting [2, 10]. Fifth, the qualitative analysis was only applied to the COVID related articles, which the quantitative analysis had already identified as more adherent to guidelines; qualitative analysis of the non-COVID articles may have revealed more harmful content; however, this was not possible due to time and resource limitations.

Perhaps the most important limitation relates to the coding schema used in this study, which was mainly inspired by the aforementioned Mindset guidelines. These may be weaker than other similar guidelines inasmuch as they do not include explicit bullet-points advising journalists to cover hopeful stories of resilience and mastery of crises, which are arguably the most important stories for suicide prevention and are instrumental in fostering a Papageno effect [3, 5, 10]. Future research should explicitly measure content related to these variables, which were omitted from the present study due to its reliance on Mindset.

Conclusion

The results from the present study indicate that the Canadian media showed partial adherence to responsible reporting of suicide recommendations, with the most adherent articles focused on suicide in the context of COVID-19. On the plus side, this adherence was higher than the year before the pandemic; however, there was still substantial room for improvement, especially in everyday routine articles about suicide and suicide deaths.

Such improvement can be fostered by a multi-pronged approach including (i) educational outreach to practicing journalists, including organized presentations by suicide experts to newsrooms, journalism unions and media organizations; (ii) seminars, workshops and trainings about responsible reporting of suicide targeted at Canadian journalism schools and journalism students to ensure that the next generation of journalists responsibly reports suicide; and (iii) further distribution and promotion of responsible reporting of suicide guidelines produced by International and Canadian organizations (16–19) to newsrooms, journalism schools and media organizations. Of note, some of these guidelines may need to be revised to ensure that they explicitly recommend content associated with a Papageno effect, such as narratives of resilience, survival stories and mastery of crisis; which also should be communicated in the above-described educational efforts. All this may foster further improvements in suicide reporting in Canada.

Data availability

The raw data for this study consists of newspaper articles. Many of these articles are behind a paywall on the news media websites listed in the paper, or only available via paid subscription to a database. Hence, we do not have the right to make these newspaper articles publicly available, as they were obtained through paid subscription to Factiva software in the current study. However, a list of the coded articles is available from the authors on reasonable request, which can be used to obtain the raw data behind the paywalls.

References

Gould MS (2001) Suicide and the media. Ann N Y Acad Sci 932(1):200–224

Sisask M, Värnik A (2012) Media roles in suicide prevention: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9(1):123–138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9010123

Niederkrotenthaler T, Voracek M, Herberth A, Till B, Strauss M, Etzersdorfer E, Eisenwort B, Sonneck G (2010) Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects Br J Psychiatry 197(3):234–243. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633

Whitley R, Fink DS, Santaella-Tenorio J, Keyes KM (2019) Suicide mortality in Canada after the death of Robin Williams, in the context of high-fidelity to suicide reporting guidelines in the Canadian media. Can J Psychiatry 64(11):805–812. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719854073

Niederkrotenthaler T, Braun M, Pirkis J, Till B, Stack S, Sinyor M, Tran US, Voracek M, Cheng Q, Arendt F, Scherr S, Yip PSF, Spittal MJ (2020) Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m575

Yang AC, Tsai SJ, Yang CH, Shia BC, Fun JL, Wang SJ, Peng CK, Huang NE (2013) Suicide and media reporting: a longitudinal and spatial analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48:427–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0562-1

Niederkrotenthaler T, Reidenberg DJ, Till B, Gould MS (2014) Increasing help-seeking and referrals for individuals at risk for suicide by decreasing stigma: the role of mass media. Am J Prev Med 47(3):S235–S243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.010

Creed M, Whitley R (2017) Assessing fidelity to suicide reporting guidelines in Canadian news media: the death of Robin Williams. Can J Psychiatry 62(5):313–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743715621255

Carmichael V, Whitley R (2018) Suicide portrayal in the Canadian media: examining newspaper coverage of the popular Netflix series ‘13 Reasons Why.’ BMC Public Health 18:1086. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5987-3

Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Nishikawa Y, Redelmeier DA, Niederkrotenthaler T, Sareen J, Levitt AJ, Kiss A, Pirkis J (2018) The association between suicide deaths and putatively harmful and protective factors in media reports. CMAJ 190(30):E900-907. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170698

Mental Health Commission of Canada (2020) COVID-19 and suicide: Potential implications and opportunities to influence trends in Canada. Mental Health Commission of Canada. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/2020-11/covid19_and_suicide_policy_brief_eng.pdf. Accessed 3 August 2021.

Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE (2020) Suicide mortality and Coronavirus disease 2019—a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiat 77(11):1093–1094. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060

Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, Hawton K, John A, Kapur N, Khan M, O’Connor RC, Pirkis J, Caine ED, Chan LF (2020) Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7(6):468–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1

Public Health Agency of Canada (2020) The federal framework for suicide prevention – progress report 2020. Catalogue no. HP32–10e-E-PDF. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/2020-progress-report-federal-framework-suicide-prevention/2020-progress-report-federal-framework-suicide-prevention-eng.pdf. Accessed 3 August 2021.

Hawton K, Marzano L, Fraser L, Hawley M, Harris-Skillman E, Lainez YX (2021) Reporting on suicidal behaviour and COVID-19—need for caution. Lancet Psychiatry 8(1):15–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30484-3

World Health Organization (2008) Preventing suicide: a resource for media professionals. World Health Organization, Geneva

AFSP (n.d.) Recommendations for reporting on suicide. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. https://afsp.org/for-journalists#resources-for-reporting-on-suicide. Accessed 3 August 2021.

Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Heisel MJ, Picard A, Adamson G, Cheung CP, Katz LY, Jetly R, Sareen J (2017) Media recommendations for reporting on suicide: 2017 update of the Canadian psychiatric association policy paper. Can J Psychiatry 63(3):182–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717753147

Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma (2020) Mindset: Reporting on mental health, 3rd edn. Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma, London

Samaritans (2013) Media guidelines for reporting suicide. Samaritans. https://www.samaritans.org/about-samaritans/media-recommendations/best-practice-suicide-reporting-tips/. Accessed 3 August 2021.

Marzano L, Hawley M, Fraser L, Harris-Skillman E, Lainez Y, Hawton K (2022) Have news reports on suicide and attempted suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic adhered to guidance on safer reporting? A UK wide content analysis study. Crisis. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000856

Lynn-Green EE, Jaźwińska K, Beckman AL, Latham SR (2021) Violations of suicide-prevention guidelines in US media coverage of physician’s suicide death during the COVID-19 pandemic. Crisis. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000778

Antebi L, Carmichael V, Whitley R (2020) Assessing adherence to responsible reporting of suicide guidelines in the Canadian news media: a 1-year examination of day-to-day suicide coverage. Can J Psychiatry 65(9):621–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720936462

Core R Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 3 August 2021.

Creswell JW (1996) Research design, qualitative and quantitative approaches. SAGE, New York

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. SAGE, New York

Whitley R, Adeponle A, Miller AR (2015) Comparing gendered and generic representations of mental illness in Canadian newspapers: an exploration of the chivalry hypothesis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50:325–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0902-4

Sinyor M, Kiss A, Williams M, Zaheer R, Pirkis J, Heisel MJ, Schaffer A, Redelmeier DA, Cheung AH, Niederkrotenthaler T (2021) Changes in suicide reporting quality and deaths in Ontario following publication of national media guidelines. Crisis 42(5):378–385. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000737

Whitley R, Wang J (2017) Good news? A longitudinal analysis of newspaper portrayals of mental illness in Canada 2005 to 2015. Can J Psyc 62(4):278–285

McIntyre RS, Lui LM, Rosenblat JD, Ho R, Gill H, Mansur RB, Teopiz K, Liao Y, Lu C, Subramaniapillai M, Nasri F, Lee Y (2021) Suicide reduction in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons informing national prevention strategies for suicide reduction. JRSM 114(10):473–479

Pirkis J, Gunnell D, Shin S, Del Pozo-Banos M, Arya V, Aguilar PA, Spittal MJ (2022) Suicide numbers during the first 9–15 months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-existing trends: An interrupted time series analysis in 33 countries. E Clin Med 51:101573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101573

Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, DelPozo-Banos M, Arya V, Analuisa-Aguilar P, Spittal MJ (2021) Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. The Lancet Psychiatry 8(7):579–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anne-Marie Saucier and Sonora Grimsted for help in managing the data during the study, as well as assisting in locating relevant statistics and background articles. We would also like to thank the Mental Health Commission of Canada for funding the study.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. RW oversaw data collection and analysis, and co-wrote the original manuscript, while taking a lead on the revision.. LA collected, analyzed and interpreted the data, and co-wrote the original manuscript. All authors read and approved the final revised manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Not applicable as no human subjects.

Data access

The data for this study consists of news media articles published in Canadian news media that were obtained via paid subscription to the Factiva software. Due to reasons of copyright and proprietary, we cannot make this data publicly available in a supplemental file.

Appendix 1: Articles about COVID-19 and suicide for qualitative analysis (n = 70)

Appendix 1: Articles about COVID-19 and suicide for qualitative analysis (n = 70)

-

1.

Toronto Sun, “‘Everybody loved’ him; Anti-establishment activist’s life ends in tragic suicide”, 19 March 2020

-

2.

Toronto Star, “Friends identify activist Derek Soberal as man who reportedly set himself on fire at Toronto gas station”, 19 March 2020

-

3.

Winnipeg Free Press, “Man avoids jail due to COVID-19”, 31 March 2020

-

4.

Toronto Star, “SIU clears police in activist’s death”, 15 April 2020

-

5.

Globe and Mail, “Caring contacts: Reaching out to the vulnerable in a pandemic”, 16 April 2020

-

6.

Calgary Sun, “Virus breeds despair; Pandemic fuelling suicide rate”, 17 April 2020

-

7.

CBC News, “Crisis lines face volunteer, cash crunch even as COVID-10 drives surge in calls", 27 April 2020

-

8.

Calgary Herald, “Suicide rates expected to rise as pandemic grinds on”, 27 April 2020

-

9.

Niagara Falls Review, “Crisis lines see surge in demand, fewer staff”, 28 April 2020

-

10.

Toronto Star, “What do we really know about suicide risk in the pandemic?”, 2 May 2020

-

11.

Global News, “Saskatchewan chief concerned about mental health impacts of COVID-19 in First Nations", 3 May 2020

-

12.

Calgary Herald, “Chiefs worry about effect of COVID-19 on mental health; First Nations struggling with stress, suicides”, 4 May 2020

-

13.

Calgary Sun, “Calls to Calgary Distress Centre spike over COVID-19 stress and anxiety", 7 May 2020

-

14.

The Guardian, “Suicide rates climb for young Nova Scotia men”, 8 May 2020

-

15.

Regina Leader-Post, “Mental health calls on rise as new supports announced; Suicide prevention plan”, 9 May 2020

-

16.

Globe and Mail, “Even when COVID-19 is beaten, the stress and depression of the pandemic will still be with us. How do we recover?”, 11 May 2020

-

17.

Toronto Star, “Fear, isolation, depression: Many across the U.S. feel the mental health fallout of a pandemic", 13 May 2020

-

18.

Saskatoon Star Phoenix, “COVID-19 compounds mental health fears in north”, 15 May 2020

-

19.

Saskatoon Star Phoenix, “Mental-health related calls to police on rise over prior two weeks”, 21 May 2020

-

20.

Regina Leader-Post, “Job loss may trigger 2,100 extra suicides; But link not direct; Get unemployed Canadians back to work, author says”, 4 June 2020

-

21.

CTV News, “As COVID-19 stress builds, study warns of potential spike in suicides”, 4 June 2020

-

22.

Calgary Sun, “‘What happened in the hospital’?; Family of B.C. man, who died in Regina, wants answers”, 8 June 2020

-

23.

Calgary Herald, “Man found dead after visit to Regina hospital; Family says new protocols may have saved him”, 8 June 2020

-

24.

Toronto Star, “Suicides could rise amid virus, study says; Research on pandemics finds link between unemployment, deaths”, 10 June 2020

-

25.

Toronto Star, “Despite far fewer riders, suicide attempts remain significant problem on TTC network amid COVID-19, new records show”, 5 August 2020

-

26.

CBC News, “25,000 Canadians hospitalized or killed by self-harm last year, research says”, 6 August 2020

-

27.

CBC News, “Mental health experts in Thunder Bay Ont. say the community 'needs more' when it comes to suicide prevention”, 14 August 2020

-

28.

CBC News, “National study says 'our children are not alright' under mounting stress of pandemic”, 1 September 2020

-

29.

Kelowna Capital News, “Increase in calls due to pandemic: Interior Crisis Line Network”, 9 September 2020

-

30.

CBC News, “You are never alone, Crisis Centre reminds everyone on World Suicide Prevention Day”, 10 September 2020

-

31.

Kelowna Capital News, “Concerns over mental health loom as B.C. enters fall during COVID-19”, 10 September 2020

-

32.

Calgary Sun, “Suicides not 'inevitable'; Open conversation one way to help: group”, 11 September 2020

-

33.

Edmonton Sun, “Suicide is not 'inevitable'; More people turning to crisis centres since pandemic began, 83.8% increase in calls”, 11 September 2020

-

34.

Saskatoon Star Phoenix, “Mother bares her grief on suicide prevention day; COVID-19 has exacerbated gaps in mental health care, advocate says”, 11 September 2020

-

35.

CTV News, “Feds to invest $11.5 million in suicide prevention for marginalized communities”, 11 September 2020

-

36.

Toronto Star, “He lost his wife. Now this man is fighting for supports during the pandemic that she did not receive”, 9 October 2020

-

37.

Toronto Star, “Pandemic's effect on mental health must not be overlooked”, 10 October 2020

-

38.

Globe and Mail, “Family demands B.C. inquiry after First Nations boy found dead in group home; The body of Driftpile Cree Nation teenager Traevon Desjarlais-Chalifoux, who was under the supervision of agency Xyolhemeylh, was undiscovered for four days”, 15 October 2020

-

39.

Prince George Citizen, “Pandemic mental health crisis calls up, suicides down”, 11 November 2020

-

40.

Calgary Herald, “Distress Centre seeks donations as COVID-19 increases demand”, 18 November 2020

-

41.

Toronto Star, “The kids are in crisis—and COVID-19 is making it worse. In Canada, deteriorating youth mental health is leaving a generation in distress”, 23 November 2020

-

42.

Toronto Star, “Seek help if you need it, Metrolinx says following string of suicide attempts on GO system”, 23 November 2020

-

43.

Waterloo Region Record, “People urged to 'put in work' to build resiliency during pandemic”, 25 November 2020

-

44.

Toronto Sun, “Help 'always' available; Metrolinx prioritizing suicide prevention”, 25 November 2020

-

45.

Toronto Star, “'A pain to be understood'”, 28 November 2020

-

46.

Globe and Mail, “Study finds jump in suicidal thoughts amid pandemic”, 3 December 2020

-

47.

Victoria Times Colonist, “B.C. funds suicide-prevention programs for Indigenous youth, post-secondary students”, 4 December 2020

-

48.

Prince George Citizen, “COVID’s second wave intensifying stress, anxiety”, 4 December 2020

-

49.

Calgary Herald, “Beginning a new life; Addiction almost destroyed Rene Desjardins”, 5 December 2020

-

50.

Toronto Star, “One in 10 Canadians say they've contemplated suicide since the pandemic began”, 5 December 2020

-

51.

Toronto Star, “Suicide crisis calls mount during COVID-19 pandemic”, 7 December 2020

-

52.

Globe and Mail, “Suicides up sharply on Toronto subway during pandemic”, 7 December 2020

-

53.

Prince George Citizen, “Nurses deal with COVID ‘terror’ as stress, burnout, suicidal thinking rise”, 10 December 2020

-

54.

CBC News, “Experts warn of pandemic's deepening impact on mental health as caseloads rise”, 17 December 2020

-

55.

Toronto Star, “More young men in Western Canada died than expected last year—and not just because of COVID-19”, 4 January 2021

-

56.

CBC News, “National organization urges N.S. to beef up mental health supports”, 5 January 2021

-

57.

Toronto Sun, “When does it stop?; Man cuffed for lockdown violation takes own life”, 6 January 2021

-

58.

CBC News, “Psychologist says 'come together effect' may have helped reduce suicides in Sask. in 2020”, 8 January 2021

-

59.

CTV News, “Que. doctor's death by suicide raises alarms over COVID-19 stress”, 10 January 2021

-

60.

Montreal Gazette, “Doctor's suicide a tragic wake-up call; Health workers need more than platitudes to combat the immense strain they're under”, 12 January 2021

-

61.

Victoria Times Colonist, “In wake of suicide, focus turns to Goldstream Trestle safety”, 20 January 2021

-

62.

Toronto Sun, “Driven to distress; Overcrowded buses and harried TTC drivers a sad reality”, 26 January 2021

-

63.

Victoria Times Colonist, “Family of teen who died by suicide says psychiatrist appointment came too late”, 28 January 2021

-

64.

Winnipeg Free Press, “Cascading crises leave Island Lake nations desperate for help”, 1 February 2021

-

65.

CTV News, “Mental health help needed for post pandemic recovery: advocates”, 1 February 2021

-

66.

Edmonton Sun, “A COVID-19 casualty we can't allow to happen", 4 February 2021

-

67.

National Post, “Guilty plea by man who rammed Rideau Hall; Reservist; Seven weapons charges, one of causing mischief”, 6 February 2021

-

68.

Global News, “‘Anxiety and depression are increasing’: Alberta doctor sees spike in mental health visits”, 6 February 2021

-

69.

CBC News, “Many assumed suicides would spike in 2020. So far, the data tells a different story”, 8 February 2021

-

70.

CBC News, “Parents of teen who took her own life say Fredericton ER failed her just days earlier”, 26 February 2021

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Whitley, R., Antebi, L. Canadian news media coverage of suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58, 1087–1098 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02430-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02430-2