Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review summarizes and presents the current state of research quantifying the relationship between mental disorder and overdose for people who use opioids.

Methods

The protocol was published in Open Science Framework. We used the PECOS framework to frame the review question. Studies published between January 1, 2000, and January 4, 2021, from North America, Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand were systematically identified and screened through searching electronic databases, citations, and by contacting experts. Risk of bias assessments were performed. Data were synthesized using the lumping technique.

Results

Overall, 6512 records were screened and 38 were selected for inclusion. 37 of the 38 studies included in this review show a connection between at least one aspect of mental disorder and opioid overdose. The largest body of evidence exists for internalizing disorders generally and mood disorders specifically, followed by anxiety disorders, although there is also moderate evidence to support the relationship between thought disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) and opioid overdose. Moderate evidence also was found for the association between any disorder and overdose.

Conclusion

Nearly all reviewed studies found a connection between mental disorder and overdose, and the evidence suggests that having mental disorder is associated with experiencing fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose, but causal direction remains unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Opioid toxicity deaths, commonly referred to as opioid overdose has become a global crisis [1, 2] that has intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. Some evidence exists to suggest that opioid overdose is commonly experienced by individuals with co-occurring mental disorder [4,5,6,7] but literature that examines these two phenomena together is sparse. This review summarizes the evidence on mental disorder and the risk of opioid overdose to advance understanding of this relationship.

Although past research indicates that individuals with mental disorders are at increased risk for overdose [8,9,10,11,12], there are multiple considerations that have precluded definitive conclusions from being made in this area. First, disentangling the symptoms of substance use disorders, other non-substance use psychiatric disorders, and medication side effects can be challenging, which complicates the identification of the relationship between mental disorder and opioid overdose. For example, individuals with mental disorders are often prescribed opioids or other psychotropic medications [13] that may interact or cumulate with non-prescription or illicit opioids to increase overdose risk. In addition, the historical expansion of diagnostic scope for mental disorders may contribute to over-pathologizing drug use, criminality, and social deviance [14]. Thus, there is difficulty in distinguishing between the presence of a mental disorder and behaviors attributable to the use of drugs, leading to imprecision in the evidence base on mental disorder and opioid use [15].

It is also unclear whether there is an identifiable causal relationship between mental disorder and opioid overdose. While stigma, stress and social exclusion commonly experienced alongside opioid use may produce poor psychological outcomes, opioids may also be used as a form of self-medication for coping with emotional pain or mental disorder symptoms [16]. Otherwise stated, the direction of causality and potential moderators in the relationship are not well understood. Another possibility in discussions about causality, and one consistent with a framework introduced by Dasgupta and colleagues [17], would reflect a process of social causation (also known as indirect selection) [18, 19], where a third factor or set of factors produces suboptimal outcomes in both areas. In this case, where opioid use and mental disorder are both hypothesized to be occurring within processes of social causation, both outcomes may be responses to social and economic precarity [16]. Importantly, scholars have also proposed a countervailing theory of social selection or social drift [20] to explain the connection between mental disorder and socioeconomic marginalization which argues for the reverse: that experiencing mental disorder causes a downward shift in social class. Given these complex pathways, a fulsome understanding of these relationships is unlikely to produce a unidirectional explanation, these pathways likely co-exist, each contributing to understandings of the complexity of the relationship between opioid overdose and mental disorder.

Despite the clear need for conclusive evidence about the intersections between mental disorder and opioid overdose, this relationship has not been clarified or summarized in a systematic way. Specifically, gaps exist in the literature in: 1) establishing the volume and strength of literature supporting the connection is between mental disorder and overdose risk; and 2) understanding the empirical evidence that exists to support the theoretical relationships hypothesized between these phenomena.

The systematic review of the extant literature on mental disorder and opioid overdose presented here began as part of a larger investigation of the literature related to socioeconomic marginalization and opioid overdose, in which we found a preponderance of scientific evidence pointing to the potential role of mental disorder [21]. This systematic review employed an integrated knowledge translation process [22] whereby we partnered with decision makers in establishing the focus of the review, refining review questions and methodology, data retrieval and retrieval tool development, interpretation of review findings, identification of gaps, crafting of recommendations, and dissemination and application of review findings. Given our initial findings, the need for an independent review on mental disorder and overdose specifically was informed by decision-makers in the local community, municipal, provincial, and federal government who required further clarity regarding the evidence on mental disorder and overdose risk. This review responds to that need and systematically summarizes the literature on whether or not broadly defined mental disorder (including both symptoms of disorder and diagnosed mental disorder) are associated with opioid overdose. The review was designed to address the above omissions, summarize existing published research, provide a knowledge base for effective prevention and response strategies, and identify future directions for policy in this area.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Using the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist, the search sought studies that included measures of mental disorder and opioid-related fatal and non-fatal overdose published in English peer-reviewed journals or by governmental sources between January 1, 2000 and January 4, 2021. Only studies conducted in North America, Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand were eligible for inclusion, as study stakeholders expressed a desire for a review of studies with the highest contextual and policy comparability. The specific terms related to mental disorder included in the search strategy are summarized in Table 1, and a summary of the Medline search terms used in the review is provided in Appendix A. The PECOS framework (Population, Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design) used to frame our specific mental disorder and opioid overdose research question [23] is listed in Table 1. Two research assistants first conducted title and abstract screening, and subsequently independently assessed full text articles to determine final inclusion eligibility. Differences in opinion about inclusion were resolved by a senior team member. More details about study selection are provided in the protocol, published on the Open Science Framework site [24].

Data collection and extraction

Two research assistants used a standardized form to extract data from the included studies, including year, journal, and type of publication, author’s name, study location, sample, study period, study design, recruitment and sampling, sample size, response rates, age range, operationalization of mental disorder, type of opioid overdose outcome, and statistical analysis. Inconsistencies in the extracted data were noted by the research assistants and resolved through discussion with a senior team member.

Study selection and data synthesis

This review approached the relationship between mental disorder (including both diagnosed disorder—medically diagnosed, assessed, or self-reported—and symptoms of disorder) and opioid overdose broadly and purposely allowed inclusion of different study types, as long as they provided evidence on the review question regarding whether mental disorder and associated symptoms are associated with increased occurrence of opioid overdose (including fatal and non-fatal overdose, overdose-related hospitalizations, and intentional vs. unintentional overdose). As a result, we employed the lumping synthesis technique where all evidence related to mental disorder and opioid overdose was included despite differences between study design and outcome measures [25]. This strategy allows for synthesis and identification of common findings in the relationships between mental disorder and opioid overdose that remain despite minor differences in study participants, context, and design, similar to the approach taken by others investigating determinants of overdose [26]. Substantial conceptual and methodological heterogeneity across the included studies precluded meta-analysis. Instead, findings are summarized by mental disorder variables. The data extraction process for this review included an assessment of bias, for which we used the study quality tools of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (presented in Table 3) [27]. Two independent reviewers assessed risk of bias.

Results

Overall findings

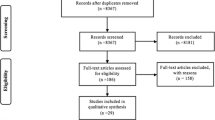

The number of studies retained in each step of the review process can be found in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1. The primary search strategy found 7200 original articles that met the initial screening criteria. The review and screening process led to a final dataset of 38 articles on mental disorder and overdose.

Eleven studies had fatal overdose as the outcome or drew their sample from a population who had experienced fatal overdose [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Thirteen included only non-fatal overdose as the sole overdose outcome in their studies [15, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], and twelve articles included both fatal and non-fatal overdose [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, 63, 64]. Two studies included data from emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations for overdose but did not specify whether the overdoses were fatal or not [61, 62]. Most studies either did not report intention of overdose (n = 17) [15, 33, 35, 39,40,41, 46, 48, 51,52,53, 58, 59, 61,62,63,64] or examined both intentional and unintentional overdose (n = 17) [30,31,32, 36,37,38, 42,43,44,45, 47, 49, 54,55,56,57, 60] with four examining only unintentional overdose [28, 29, 34, 50]. Many studies (n = 20) included overdose that was attributable to prescription and non-prescription opioids [29, 32, 35,36,37, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47, 49, 50, 56,57,58, 60, 63, 64], while eleven investigated only prescription opioid overdoses [28, 33, 34, 38, 48, 51,52,53,54, 61, 62] and two investigated only non-prescription opioid overdoses [15, 39]. Five studies did not report what type of opioids were included in their data [30, 31, 40, 55, 59]. The included studies analyzed data from the United States (n = 28) [28,29,30,31,32, 34, 35, 42,43,44,45,46, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, 61,62,63,64], Australia (n = 4) [15, 36, 39, 47], Canada (n = 4) [33, 37, 38, 60], Italy (n = 1) [40] and Spain (n = 1) [41]. Study designs included nine cross-sectional analyses [15, 29, 37, 39, 40, 42, 45, 49, 50], fourteen cohort studies [32, 35, 41, 43, 44, 46, 51,52,53,54,55, 58, 59, 63], eight case–control studies [33, 34, 38, 47, 56, 57, 60, 64] two studies that used nested case–control designs [48, 61] two ecological studies [30, 31] one study that used panel data [36] and one study that used a case-cohort design [28]. A summary of the study design, data sources, and sample characteristics for the 38 included studies can be found in Table 2.

The majority of the 38 included studies operationalized mental disorder through diagnosed mental disorder, with only six studies reporting on symptoms of disorder [29, 38,39,40, 42, 45]. Overall, 37/38 of these studies found a significant association with the mental disorder and opioid overdose variables used, with the direction of the association suggesting that people experiencing mental disorder and associated symptoms were more likely to overdose than those who were not. Only one study presented results in the opposite direction [32]. A summary of measures and findings for the 38 included studies can be found in Table 3.

Risk of bias within included studies

The risk of bias assessments indicated a mix of bias-related concern with 10/38 of the original papers having ‘poor’ assessments, 20/38 having ‘fair’ assessments, and 8/38 studies having ‘good’ assessments. Many studies only measured exposure variables once during the study; failed to include multivariable controls for potential confounding variables; did not report information about power, effect estimates, or sample size justifications; or presented bivariable relationships only. The most serious concerns about risk of bias in the included studies arise from mental disorder variables only being assessed once or being assessed after the outcome [15], and inconsistent measurement of mental disorder across groups [29]. The dataset is largely observational, limiting causal conclusions. Results from included studies are organized in the below summary by mental disorder categories.

Internalizing disorders

The evidence on internalizing mental disorders and opioid overdose, including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive and related disorders, trauma and stressor-related disorders are summarized by specific disorder below.

Mood disorders

Twenty-four studies examined the connection between mood disorders and overdose, and 17/24 of these studies found mood disorders to be significantly and positively associated with opioid-related overdose. This association has been found in the general population: across US states (AIRR 1.26, 95% CI 1.01–1.58 [30]), in California and Florida (AOR 2.71, 95% CI 2.46–2.97, p < 0.001 [44]), in Ontario, Canada (AOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.00–3.24; [33]),and in British Columbia (men: 34.0% vs. 7.9%, p < 0.01; women: 52.0% vs. 13%, p < 0.01; [60]. Depression has been found to be associated with opioid overdose among Medicare/Medicaid enrollees: in Pennsylvania (adjusted OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12–1.50) [53], in Oregon (28.0% vs. 10.9%, p < 0.001 [57]), and nationally in the US (56.8% vs. 30.2%; [32]. Associations between depression and overdose were also present in samples that studied those with substance use disorders specifically: in New South Wales (non-fatal overdose and suicide attempt AOR 1.71, 95% CI 1.17–2.51, p < 0.05Footnote 1 [47]), in Boston (AOR 2.46, 95% CI 1.24–4.89; [43]),and in Madrid (AOR 2.20, 95% CI 1.01–4.74; [41].

This association has also been found among patients with opioid prescriptions in two national US studies (311/100,000 person-years, 95% CI 203–441 vs. 96/100,000 person-years, 95% CI 62–137) [54] and (AOR 3.12, 95% CI 2.84–3.42) [48] and in North Carolina (AHR 2.30, 95% CI 1.98–2.68) [51].Footnote 2 Significant associations were additionally found using data from community hospitals across the US (prescription opioids, males: ARR 1.10 (95% CI 1.05–1.15, p < 0.001), females: ARR 1.12 (95% CI 1.08–1.15, p < 0.001)) [50], electronic health records data (repeat overdose, AHR 1.38, 95% CI 1.02–1.73 [63]). A connection between depression and overdose was also present in studies of commercially insured adolescents (AHR 2.77, 95% CI 2.26–3.34 [62]), pregnant/postpartum women (depression prevalence with overdose 84.8% vs. opioid use disorder 61.2% vs. neither 18.9%, p < 0.001 [59], and Veterans Health Administration claims (56.4% vs. 36.7%, p < 0.0001 [46]. Non-significant findings or findings that did not retain significance in multivariable analysis include those from a study with Veterans Health Administration patients [64], those eligible for Medicaid in Oklahoma [34],the general population of US adults [31], repeat overdose events [49, 58],commercially insured individuals [55], and young people who use heroin in Australia [39].

Anxiety disorders

Seventeen studies examined the connection between anxiety disorders and overdose, and 12 of these studies found a significant association. Those with anxiety disorders were more likely to experience opioid overdose in Ontario (cases 63.2% vs. controls 54.9%, standardized difference = 0.13; [38]), in British Columbia (men: 30.0% vs. 6.8%, p < 0.01; women: 45.0% vs. 11.0%, p < 0.01; [60]), and in people presenting to an emergency department in Pennsylvania (repeat overdose AHR 1.41, 95% CI 1.13–1.77; [63]). These association were also seen in two national samples of the Medicare enrollee population (adjusted OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.07–1.48) [53] (63.4% vs. 30.9%) [32], as well as the commercially insured population in four studies: three with adult populations (AOR (95% CI) 1.64 (1.50–1.80) [48]), AOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.12–1.36 [55], repeat overdose events for those with anxiety 39.5% vs. 47.0%, p = 0.013 [58]), and one with adolescents (prescription opioid overdose AHR 1.65, 95% CI 1.33–2.06; [62]). Other samples where this relationship was seen include those with substance use disorder in New South Wales (non-fatal overdose and suicide attempt AOR 1.71, 95% CI 1.17–2.51, p < 0.05Footnote 3,association not present in subgroup analysis [47]),among Veterans Health Administration claims (anxiety in those with overdose 22.3% vs. non-opioid related hospitalizations 15.1%, p < 0.05Footnote 4; [46], and in a cohort of pregnant/postpartum women (prevalence of anxiety among those with overdose 82.1% vs. opioid use disorder 60.2%, vs. neither 18.3% p < 0.001 [59]. Non-significant findings were present in Veterans Health Administration patients [64], decedents eligible for Medicaid in Oklahoma [34], samples of inpatient populations [42, 50] and people with substance use disorders in Boston [43].

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive compulsive disorder and adjustment disorders

Ten studies examined other internalizing disorders including posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and adjustment disorders. Six of these studies found significant associations, five of which were in the hypothesized direction. Studies in this review found a significant positive association between PTSD and opioid overdose among people with substance use disorders in Boston (non-fatal overdose AOR 2.77, 95% CI 1.37–5.60; [43]), those recruited from methadone or residential detox programs in New Jersey (AOR 3.84, 95% Cl l.41–10.46, p = 0.01 [45]), and in Veterans Health Administration claims (claims for opioid overdose hospitalizations vs. non-opioid hospitalizations 30.4% vs. 19.0%, p < 0.0001Footnote 5) [46]. Similar trends were seen with past year affective disorder in Ontario (case 11.2% vs. controls 5.6%, Standardized Difference = 0.19 [38]Footnote 6), and past 5-year adjustment disorder in British Columbia (men: cases 16.0% vs. controls 2.4%, p < 0.01, women: 25.0% vs. 4.7%, p < 0.01) [60]. Conversely, one study found a negative association with PTSD and fatal opioid overdose among Medicare enrollees in the US (AOR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58–0.92 [32]). Four studies failed to find significant associations or found bivariable associations that did not retain significance in multivariable models in the commercially insured population [48, 55], veterans [48, 64], and Medicare enrollees in Pennsylvania [53].Footnote 7

Externalizing disorders

The evidence on opioid overdose and externalizing disorders is summarized below by disorder type, in this case, for personality disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Personality disorders and antisocial behavior

Five studies examined personality disorders and associated antisocial behaviors and 4/5 of these studies found significant associations with higher rates of opioid overdose. Associations between antisocial personality disorder and non-fatal opioid overdose were seen in two studies conducted with people who use heroin in Australia (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.15–4.21 [15], Wald’s statistic: 8.21, p < 0.01 [39]). Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have had a prior personality disorder compared to those with no overdose when measured in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in the United States (9.8% vs 4.1%, p < 0.001) [32], and in British Columbia (for men past year personality disorder 3.3% vs. 0.16%, p < 0.01, and women 5.2% vs. 0.16%, p < 0.01) [60]. One study done in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in Pennsylvania found no significant associations [53].

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Four studies in this review investigated the association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and opioid overdose. Two of these studies found significant associations. Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have ADHD compared to those with no overdose when measured in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in the United States (12.0% vs 4.6%, p < 0.001) [32], and in British Columbia (for men past year prevalence 1.9% vs. 0.35%, p < 0.01, and women 1.2% vs. 0.30%, p < 0.01) [60]. Studies done with the commercially insured [48] and veteran population [48, 64] found no association with opioid overdose.

Thought and other disorders

Similar to other reviews in this area [65], we have additionally summarized the evidence for thought disorders and overdose, including bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia and psychoses (otherwise undefined).

Schizophrenia and psychoses

Schizophrenia and psychoses were examined in eight included studies, and five found significant associations with opioid overdose. A relationship between psychoses and overdose was seen among people prescribed opioids in the commercially insured population (schizophrenia AOR 2.06, 95% CI 1.17–3.69) [48], the general population in California and Florida (psychoses and hospitalization AOR 5.40, 95% CI 4.85–6.00, p < 0.001, psychoses and frequency of ED visits AOR 1.44, 95% CI 1.25–1.65, p < 0.001 for opioid overdose) [44], and patients with hospital stays for opioid overdose in a US-based national cohort (AOR: 1.25, 95% CI:1.01–1.53) [49]. Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have schizophrenia or psychoses compared to those with no overdose when measured in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in the United States (18.8% vs 11.5%, p < 0.001) [32], and in British Columbia (for men past year prevalence 7.0% vs. 0.93%, p < 0.01, and women 7.3% vs. 0.38%, p < 0.01) [60].

Non-significant findings between schizophrenia and opioid overdose came from studies done with veterans [64], patients receiving methadone [33], and ED patients in Pennsylvania [63].

Bipolar disorders

Ten studies examined bipolar disorder and opioid overdose, and nine found associations with overdose. Bipolar disorder was associated with overdose in an Australian study of people with substance use disorder (OR 3.37, 95% CI 1.44–7.88) [15], in commercially insured (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.83–2.60) [48] and veteran populations prescribed opioids in the US,(OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.17–2.43) [48], and for females (ARR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00–1.12, p < 0.05) but not males who were prescribed opioids [50]. Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have bipolar disorder than controls when measured: in a cohort of Medicare enrollees across the US (AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.28–1.79) [32], among members of Oklahoma’s Medicaid program (AOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.20–2.65) [34], in patients of the Veterans Health Administration (AOR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.4, p = 0.005) [64], among patients with repeat overdose in California (22.3% vs. 14.8%, p < 0.001) [58], in those with both opioid overdose and suicide attempt in New South Whales (AOR 2.29, 95% CI 1.55–3.34, p < 0.001Footnote 8 [47]), and in both men (past year disorder 6.3% vs. 0.82%, p < 0.01) and women (11% vs. 1%, p < 0.01) in British Columbia [60]. A multivariable analysis on a retrospective cohort of persons with non-fatal opioid overdose in Pennsylvania did not find a significant association with bipolar disorder [63].

Any disorder and psychological distress

Some included papers looked at combined measures of any mental disorder and opioid overdose or investigated symptoms of mental disorder in the form of suicidality and hopelessness, or intent of opioid overdose. The results of those papers are summarized below.

Any disorder

Twelve studies included in the review examined any combined measures of mental disorder and 10/12 found significant associations with opioid overdose events. Mental disorder diagnosis was significantly associated with overdose: among those prescribed long-term opioid therapy in Colorado (adjusted matched OR 2.97, 95% CI 1.57–5.64) [56], for commercially insured patients in the US (AOR 3.14; 95% CI 2.40–4.12) [52], among three subpopulations of US veterans who were prescribed opioids (those with chronic pain AHR 1.87, 95% CI 1.48–2.38; acute pain AHR 1.77, 95% CI 1.19–2.65; and substance use disorder AHR 1.73, 95% CI 1.10–2.72) [28], and in ED patients in Pennsylvania (repeat overdose AHR 1.32, 95% CI 1.08–1.61) [63]. Similar trends were seen for former inmates who received prior in-prison mental disorder treatment (1-year post release AHR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.7–2.9) [35], and in patients on Medicaid with a history of mental disorder (hospitalization/ED visit for overdose AOR 1.73, 95% CI 1.31–2.29) [61]. When compared to controls, those with overdose were more likely to have a history of mental disorder or serious mental illness, a trend present among patients of mental hospitals in the US (72.2% vs. 50.0%, p = 0.013) [42], in a study of US veterans prescribed opioids (24.2% vs 9.7%, p < 0.0001 for opioid related hospitalizations) [46], in young people using heroin in Australia (Wald’s statistic: 4.15, p < 0.05) [39], and in fatal opioid overdose cases in Utah [50.0% vs. 15.0%, p < 0.001Footnote 9) [29]. However, two bivariable analyses found no association between mental disorder and non-fatal opioid overdose in California [58], or in therapeutic communities in Italy [40].

Suicidality and self-harm

Three studies examined symptoms of mental disorder and opioid overdose and 2/3 found significant associations. Opioid overdose was associated with hopelessness in young people who use heroin in Australia (hopelessness, Wald’s statistic: 6.12, p < 0.01; self-harm, non-significant) [39] and with history of suicide among adults recruited from psychiatric hospitals in the US (50% vs. 17.2%, p = 0.001) [42]. In a cross-sectional study in New Jersey, no significant bivariable relationship was detected between suicidal ideation and non-fatal opioid overdose [45].

Intentionality

Three of the papers that grouped mental disorders together or examined symptoms of mental disorder specifically looked at associations with likelihood of an intentional (vs. unintentional) opioid overdose, and all found disorders/symptoms to be associated with intentional overdose. These bivariable associations were seen in Australia, for those with a history of mental health problems recorded in the National Coronial Information System (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.6–2.7) [36] and in Ontario, for those with a diagnosed disorder (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.4–3.2, p = 0.0005) [37]. In a different study of Ontario residents, people with fatal intentional opioid overdose were more likely to have a history of self-harm in the year preceding death than people with fatal accidental opioid overdose (standardized difference: 0.26) [38].

Discussion

Summary of findings

Overall, 37/38 studies included in this review show a connection between mental disorders and opioid overdose with only one association reported that was not in the hypothesized direction. The largest volume of evidence was found for internalizing disorders generally and mood disorders specifically, although there was also moderate evidence to support the relationship between anxiety disorders and opioid overdose. The presence of thought disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, BPD) appears to be associated with opioid overdose. When studies included multiple disorders together in their analyses, evidence was found for the association between any disorder and overdose. Fewer studies investigated externalizing disorders, but most studies that looked at personality and anti-social disorders found significant associations with opioid overdose. The relationship between mental disorder and opioid overdose appears to be present in the general population, among people who use prescription opioids, Medicare/Medicaid enrollees, youth, and veterans. Included studies did not examine variations in these relationships by race/ethnicity, and very few examined differences by gender. Mental disorders may be more common among those who have intentional opioid overdose than unintentional opioid overdose, but more evidence is required to confirm this. Given our findings, it is apparent that mental disorder plays a role in opioid overdose. However, there was substantial variation in measurement and type of independent and dependent variables examined, as well as in the populations and study settings, limiting more nuanced conclusions about this relationship.

Limitations

We reviewed the literature on a wide range of mental disorder issues and opioid overdose. To make the results of our review widely applicable for those making decisions in the overdose crisis, we chose to include studies with any type of opioid overdose measure in the review. By undertaking a broad review, we were able to explore whether the associations between mental disorder and opioid overdose were similar across different disorders, different settings, and different populations. A narrower review would have reduced the number of included studies and thus may have been more susceptible to erroneous conclusions [66]. However, including a variety of outcome measures also presents limitations, including the inability to identify unique risks from different outcomes (e.g., fatal and non-fatal overdose) and the inability to conduct statistical meta-analyses. There were no experimental study designs or mediation analyses among the included papers and this limits any ability to derive causal pathways or make more definitive conclusions about the way mental disorder is related to opioid overdose.

Future directions

The lack of conclusive findings on causal relationships connecting mental disorder to opioid overdose is a challenge that could be first met with qualitative research conducted to elucidate the pathways and mechanisms linking these two phenomena. In recognition of the structural factors intersecting with the opioid crisis including, for example, diminished economic opportunity, colonization, racialization, increasing isolation, and income inequality, more attention should be given to the way these shared root causes impact mental disorder and opioid use [17, 67] and the potential for variation in outcomes for people affected by these structural factors.

Additionally, more quantitative research is needed to determine causal direction in the relationships and whether the connection between mental disorder and opioid overdose is in part a result of a connection to socioeconomic marginalization either through social selection [20], social causation [68, 69], or both. Although none of the studies included in this review examined casual direction, given the severity of the overdose emergency, it remains imperative that we pursue such an understanding in efforts to mitigate the catastrophic crisis. Recent studies have examined “diseases of despair,” or the connected trends of increasing fatal drug overdose, suicide, and alcohol-related illness [18, 19, 70] and found common causes to each population health challenge. Analyzing these trends reveals complex and interrelated environmental, contextual and social issues associated with the increase in overdose [71] including deepening socioeconomic marginalization, [72,73,74] chronic physical pain, [75] disconnection, and hopelessness [70]. These same factors are also associated with mental disorder, leading scholars to suggest that the connection between these phenomena may have roots in social distress and economic hardship [17] that require further investigation.

The literature included in this review largely focused on diagnosed mental disorder. This is further complicated by the variety of different types of mental disorders, and the possibility exists that the relationships differ by type of disorder, an area worthy of further investigation. We included search terms designed to identify studies that measured exclusion, hopelessness, isolation, stigma, and symptoms of mental disorder more broadly, but found little empirical research published in this area. Thus, more research is needed on not just diagnosed mental disorder and opioid overdose, but also the associated phenomena that may be affecting overdose risk.

Individuals struggling concurrently with mental disorder and opioid use experience higher levels of complexity in symptoms, face more pronounced exclusion, require more integrated treatment, have poorer outcomes, and incur higher costs [76]. Therefore, integrated clinical, policy, and programmatic responses are critically needed, and future research should focus on developing evidence that can support such a response.

In conclusion, based on the included studies, those with mental disorders appear to be at increased risk of intentional and unintentional fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose, with both prescription and non-prescription opioids, and these associations have been found to exist in a wide variety of subpopulations. A complete understanding of the relationship requires more empirical evidence related to directionality, the social and structural root causes of mental disorder, and the implications for different subgroups of the population and for disorders with differing etiology [77].

Availability of data and material

Not applicable. (All studies included in the review are available publicly.)

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Association was not present in subgroup analysis.

This study did not differentiate results for those with depressive/mood disorders from those with anxiety disorders, and results have been included in the mood disorder category due to the higher prevalence of mood than anxiety disorders in the population.

Association was not present in subgroup analysis.

P value presented only for opioid vs. non-opioid related hospitalizations.

P value compares opioid-related hospitalizations with non-opioid-related hospitalizations.

The definition used for affective disorder was not provided, and thus, results are reported in this section given the potential inclusion of multiple mood disorders.

The definition of adjustment disorders and “miscellaneous other disorders” was not provided, results are reported in this section given the potential inclusion of multiple mood disorders.

Association was not present in subgroup analysis.

Notably, the bivariable, uncontrolled analyses used different measures of mental disorder in the two groups being compared, making comparisons difficult.

References

Degenhardt L et al (2013) Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 382(9904):1564–1574

Chen Y, Shiels MS, Thomas D, Freedman ND, Berrington de González A (2019) Premature mortality from drug overdoses: a comparative analysis of 13 organisation for economic co-operation and development member countries with high-quality death certificate data, 2001 to 2015. Ann Intern Med 170(5):352–354

BC Coroners Service Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General, “Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC January 1, 2010–April 30, 2020,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2020

Bjornaas MA, Teige B, Hovda KE, Ekeberg O, Heyerdahl F, Jacobsen D (2010) Fatal poisonings in Oslo: a one-year observational study. BMC Emerg Med 10(1):1–11

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6):593–602

Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF (2006) Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 67(2):247–257

Grant BF et al (2005) Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 66(10):1205–1215

Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC (2012) Risk of death from accidental overdose associated with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 169(1):64–70

Hall AJ et al (2008) Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA 300(22):2613–2620

Galea S et al (2006) Heroin and cocaine dependence and the risk of accidental non-fatal drug overdose. J Addict Dis 25(3):79–87

Tobin KE, Latkin CA (2003) The relationship between depressive symptoms and nonfatal overdose among a sample of drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. J Urban Heal 80(2):220–229

Toblin RL, Paulozzi LJ, Logan JE, Hall AJ, Kaplan JA (2010) Mental illness and psychotropic drug use among prescription drug overdose deaths: a medical examiner chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 71(4):491–496

Braden JB et al (2009) Trends in long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain among persons with a history of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31(6):564–570

Hare RD (1980) A research scale for the assessment of psychopathy in criminal populations. Pers Individ Dif 1(2):111–119

Darke S, Ross J, Williamson A, Mills KL, Havard A, Teesson M (2007) Borderline personality disorder and persistently elevated levels of risk in 36-month outcomes for the treatment of heroin dependence. Addiction 102(7):1140–1146

Gregg L, Barrowclough C, Haddock G (2007) Reasons for increased substance use in psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev 27(4):494–510

Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D (2018) Opioid crisis: no easy fix to its social and economic determinants. Am J Public Health 108(2):182–186

Meit M, Hefferman M, Tanenbaum E, Hoffmann T (2017) Final report: Appalachian diseases of despair,” Bethesda, MD Walsh Cent. Rural Heal. Anal. NORC Univ. Chicago. https://www.arc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AppalachianDiseasesofDespairAugust2017.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2020

Stein EM, Gennuso KP, Ugboaja DC, Remington PL (2017) The epidemic of despair among white Americans: trends in the leading causes of premature death, 1999–2015. Am J Public Health 107(10):1541–1547

Fox JW (1990) Social class, mental illness, and social mobility: the social selection-drift hypothesis for serious mental illness. J Health Soc Behav 31:344–353

van Draanen J, Tsang C, Mitra S, Karamouzian M, Richardson L (2020) Socioeconomic marginalization and opioid-related overdose: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 214:108127

Bowen S, Graham I (2013) Integrated knowledge translation. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I (eds) Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester UK, pp 14–23. https://ktru.iums.ac.ir/files/ktru/files/KT_in_HeaLth_Care-2013.pdf

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P (2007) Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 7(1):1–6

van Draanen J, Tsang C, Mitra S, Phuong V, Murakami A, Karamouzian M, Richardson L (2021) Mental health and opioid overdose: a systematic review protocol. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/bt62x/. Accessed 20 April 2021

Hussong AM, Ennett ST, Cox MJ, Haroon M (2017) A systematic review of the unique prospective association of negative affect symptoms and adolescent substance use controlling for externalizing symptoms. Psychol Addict Behav 31(2):137–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000247

King NB, Fraser V, Boikos C, Richardson R, Harper S (2014) Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 104(8):e32–e42

N. I. of Health, “Study quality assessment tools.” https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 3 Mar 2019

Bohnert ASB et al (2011) Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA 305(13):1315–1321

Cheng M, Sauer B, Johnson E, Porucznik C, Hegmann K (2013) Comparison of opioid-related deaths by work-related injury. Am J Ind Med 56(3):308–316

Foley M, Schwab-Reese LM (2019) Associations of state-level rates of depression and fatal opioid overdose in the United States, 2011–2015. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54(1):131–134

Gerhart J et al (2020) Geopersonality of preventable death in the United States: anger-prone states and opioid deaths. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 37(8):624–631

Kuo Y-F, Raji MA, Goodwin JS (2019) Association of disability with mortality from opioid overdose among US medicare adults. JAMA Netw Open 2(11):e1915638–e1915638

Leece P et al (2015) Predictors of opioid-related death during methadone therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat 57:30–35

Pham TT, Skrepnek GH, Bond C, Alfieri T, Cothran TJ, Keast SL (2018) Overview of prescription opioid deaths in the Oklahoma State Medicaid population, 2012–2016. Med Care 56(8):727–735

Ranapurwala SI et al (2018) Opioid overdose mortality among former North Carolina inmates: 2000–2015. Am J Public Health 108(9):1207–1213

Roxburgh A et al (2015) Trends and characteristics of accidental and intentional codeine overdose deaths in Australia. Med J Aust 203(7):299

Madadi P, Hildebrandt D, Lauwers AE, Koren G (2013) Characteristics of opioid-users whose death was related to opioid-toxicity: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 8(4):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060600

Mazereeuw G et al (2020) Oxycodone, hydromorphone, and the risk of suicide: a retrospective population-based case-control study. Drug Saf 43(8):737–743

Burns JM, Martyres RF, Clode D, Boldero JM (2004) Overdose in young people using heroin: associations with mental health, prescription drug use and personal circumstances. Med J Aust 181:S25–S28

Carrà G et al (2017) Area-level deprivation and adverse consequences in people with substance use disorders: findings from the psychiatric and addictive dual disorder in Italy (PADDI) study. Subst Use Misuse 52(4):451–458

Chahua M et al (2014) Non-fatal opioid overdose and major depression among street-recruited young heroin users. Eur Addict Res 20(1):1–7

Connery HS et al (2019) Suicidal motivations reported by opioid overdose survivors: a cross-sectional study of adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 205:107612

Fendrich M, Becker J, Hernandez-Meier J (2019) Psychiatric symptoms and recent overdose among people who use heroin or other opioids: Results from a secondary analysis of an intervention study. Addict Behav Rep 10:100212

Hasegawa K, Brown DFM, Tsugawa Y, Camargo CA Jr (2014) Epidemiology of emergency department visits for opioid overdose: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc 89(4):462–471

Kline A et al (2021) Opioid overdose in the age of fentanyl: risk factor differences among subpopulations of overdose survivors. Int J Drug Policy 90:103051

Lagisetty PA, Lin LA, Ganoczy D, Haffajee RL, Iwashyna TJ, Bohnert A (2019) Opioid prescribing following opioid-related inpatient hospitalizations by diagnosis: a cohort study. Med Care 57(10):815

Maloney E, Degenhardt L, Darke S, Nelson EC (2009) Are non-fatal opioid overdoses misclassified suicide attempts? Comparing the associated correlates. Addict Behav 34(9):723

Nadpara PA et al (2018) Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose: comparison of commercially insured and veterans health affairs populations. Pain Med 19(1):79–96

Peterson C, Liu Y, Xu L, Nataraj N, Zhang K, Mikosz CA (2019) US national 90-day readmissions after opioid overdose discharge. Am J Prev Med 56(6):875–881

Yoon Y-H, Chen CM, Yi H-Y (2014) Unintentional alcohol and drug poisoning in association with substance use disorders and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Inj Prev 20(1):21–28

Campbell CI, Bahorik AL, VanVeldhuisen P, Weisner C, Rubinstein AL, Ray GT (2018) Use of a prescription opioid registry to examine opioid misuse and overdose in an integrated health system. Prev Med (baltim) 110:31–37

Chua K-P, Brummett CM, Conti RM, Bohnert A (2020) Association of opioid prescribing patterns with prescription opioid overdose in adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr 174(2):141–148

Cochran G et al (2017) Medicaid prior authorization and opioid medication abuse and overdose. Am J Manag Care 23(5):e164

Dunn KM et al (2010) Overdose and prescribed opioids: associations among chronic non-cancer pain patients. Ann Intern Med 152(2):85

Follman S, Arora VM, Lyttle C, Moore PQ, Pho MT (2019) Naloxone prescriptions among commercially insured individuals at high risk of opioid overdose. JAMA Netw Open 2(5):e193209–e193209

Glanz JM, Binswanger IA, Shetterly SM, Narwaney KJ, Xu S (2019) Association between opioid dose variability and opioid overdose among adults prescribed long-term opioid therapy. JAMA Netw Open 2(4):e192613–e192613

Hartung DM et al (2020) Prescription opioid dispensing patterns prior to heroin overdose in a state medicaid program: a case-control study. J Gen Intern Med 35(11):3188–3196

Karmali RN, Ray GT, Rubinstein AL, Sterling SA, Weisner CM, Campbell CI (2020) The role of substance use disorders in experiencing a repeat opioid overdose, and substance use treatment patterns among patients with a non-fatal opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend 209:107923

Schiff DM et al (2018) Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet Gynecol 132(2):466

Smolina K et al (2019) Patterns and history of prescription drug use among opioid-related drug overdose cases in British Columbia, Canada, 2015–2016. Drug Alcohol Depend 194:151–158

Dilokthornsakul P et al (2016) Risk factors of prescription opioid overdose among Colorado Medicaid beneficiaries. J Pain 17(4):436–443

Groenewald CB, Zhou C, Palermo TM, Van Cleve WC (2019) Associations between opioid prescribing patterns and overdose among privately insured adolescents. Pediatrics 144(5):e20184070

Suffoletto B, Zeigler A (2020) Risk and protective factors for repeated overdose after opioid overdose survival. Drug Alcohol Depend 209:107890

Zedler B et al (2014) Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-related toxicity or overdose among Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med 15(11):1911–1929

Castillo-Carniglia A, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, Cerdá M (2019) Psychiatric comorbidities in alcohol use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry 6(12):1068–1080

Gøtzsche PC (2000) Why we need a broad perspective on meta-analysis: it may be crucially important for patients. BMJ 321:585–586. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7261.585

Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M (2014) Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry 26(4):392–407

Hudson CG (2005) Socioeconomic status and mental illness: tests of the social causation and selection hypotheses. Am J Orthopsychiatry 75(1):3–18

Wadsworth ME, Achenbach TM (2005) Explaining the link between low socioeconomic status and psychopathology: testing two mechanisms of the social causation hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol 73(6):1146

Auerbach J, Miller BF (2018) Deaths of despair and building a national resilience strategy. J Public Health Manag Pract 24(4):297–300. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000835

Madras BK (2017) The surge of opioid use, addiction, and overdoses: responsibility and response of the US health care system. JAMA Psychiat 74(5):441–442

Zlotorzynska M, Milloy MJ, Richardson L, Nguyen P, Montaner J, Wood E, Kerr T (2014) Timing of income assistance payment and overdose patterns at a canadian supervised injection facility. Int J Drug Policy 25(4):736–739

Xiang Y, Zhao W, Xiang H, Smith GA (2012) ED visits for drug-related poisoning in the United States, 2007. Am J Emerg Med 30(2):293–301

Lanier WA, Johnson EM, Rolfs RT, Friedrichs MD, Grey TC (2012) Risk factors for prescription opioid-related death, Utah, 2008–2009. Pain Med 13(12):1580–1589

Simon LS (2012) Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 26(2):197–198

Tiet QQ, Mausbach B (2007) Treatments for patients with dual diagnosis: a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31(4):513–536

Crawford V, Crome IB, Clancy C (2003) Co-existing problems of mental health and substance misuse (dual diagnosis): a literature review. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 10(1):1–74

Funding

This study was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Knowledge Synthesis Grant (OCK-156771) as well as a CIHR Foundation grant (CIHR; FDN-154320) that supports the research activities of LR. LR is additionally supported through the Canada Research Chairs program by a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Social Inclusion and Health Equity. JVD is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellow Award from CIHR and a Research Trainee award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. SM is supported by a Doctoral Research Award from CIHR. MK is supported by Vanier Canada Graduate and Pierre Elliott Trudeau Doctoral Scholarships. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LR and JVD were responsible for conceptualization. LR was responsible for supervision, funding acquisition, and writing (review and editing). JVD was responsible for project administration, formal analysis, methodology, and writing (original draft preparation). CT, VP, and AM were responsible for formal analysis, investigation, and writing (review and editing). SM was responsible for formal analysis and investigation. MK was responsible for data curation and methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors of this report have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

Not applicable. (This study is a systematic review and did not require ethical approval as no human subject research was conducted.)

Appendix A. Medline search strategy

Appendix A. Medline search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) < 1946 to January 4, 2021 > |

Search Strategy: 1 mental disorders/or anxiety disorders/or "bipolar and related disorders"/or "disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders"/or dissociative disorders/or elimination disorders/or mood disorders/or motor disorders/or neurocognitive disorders/or neurodevelopmental disorders/or personality disorders/or "schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders"/or "trauma and stressor related disorders"/(238,726) 2 affective disorders, psychotic/or capgras syndrome/or delusional parasitosis/or morgellons disease/or paranoid disorders/or psychotic disorders/or psychoses, substance-induced/or schizophrenia/(144,299) 3 Mental Health/(40,321) 4 depressive disorder/or depression, postpartum/or depressive disorder, major/or depressive disorder, treatment-resistant/or dysthymic disorder/or premenstrual dysphoric disorder/or seasonal affective disorder/(110,300) 5 Anxiety/(83,253) 6 anxiety disorders/or agoraphobia/or anxiety, separation/or neurocirculatory asthenia/or neurotic disorders/or obsessive–compulsive disorder/or panic disorder/or phobic disorders/(79,407) 7 phobic disorders/or phobia, social/(11,399) 8 Depression/(122,161) 9 stress disorders, traumatic/or psychological trauma/or stress disorders, post-traumatic/or stress disorders, traumatic, acute/(35,256) 10 "attention deficit and disruptive behavior disorders"/or attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity/or conduct disorder/(33,384) 11 (Psychiatric or Mental Disorder* or Depress* or MDD or Bipolar or Panic or Anxiety or Phobia or PTSD or ADHD or Schizophrenia or mental or stress or "attention deficit" or "major depress*" or "post trauma*").ti,ab. (1,788,015) 12 exp Opioid-Related Disorders/(27,403) 13 Opioid-Related Disorders.ti,ab. (22) 14 exp Analgesics, Opioid/(117,988) 15 opioid analgesics.ti,ab. (3549) 16 exp Narcotics/(126,090) 17 Narcotics.ti,ab. (5860) 18 exp Morphinans/(80,736) 19 Morphinans.ti,ab. (109) 20 exp Methadone/(12,542) 21 exp Fentanyl/(16,003) 22 Tramadol/(3179) 23 Prescription Drug Misuse/(1900) 24 Prescription Drug Overuse/(324) 25 (Heroin Dependence or Morphine Dependence or Opium Dependence or Prescription Drug Misuse or Prescription Drug Overuse).ti,ab. (1684) 26 (Abstral or Actiq or Avinza or Codeine or Demerol or Meperidine or Pethidine or Dilaudid or Dolophine or Duragesic or Doloral or Fentora or Fentanyl or Sufentanil or Sufenta or Carfentanil or Carfentanyl or Hydrocodone or Hysingla ER or Methadose or Methadon$ or Metadol or Morphabond or Nucynta ER Onsolis or Oramorph or Oxaydo or RoxanolT or Sublimaze or Xtampza ER or Zohydro ER or BuTrans or Suboxone or Statex or Talwin or Nucynta or Ultram or Tramacet or Tridural or Tramadol or Durela or Dihydromorphine or Ethylmorphine or Hydromorphone or Thebaine or Levorphanol or Morphin* or Morfin* or Hydroxycodeinon or Oxiconum or Oxycone or Oxycontin or Oxycodone or Oxymorphone or Pentazocine or Propoxyphene or Fiorional or Robitussin or Empirin or Roxanol or Duramorph or Tylox or Tramal or Dipipanone or Remifentanil or Papaveretum or Tapentadol or Opioid* or Opiate* or Heroin or Opium or Subutex or Buprenex or Buprex or Buprine).ti,ab. (186,427) 27 (Anexsia or Co-Gesic or Embeda or Exalgo or Hycet or Hycodan or Hydromet or Ibudone or Kadian or Liquicet or Lorcet or Lorcet Plus or Lortab or Maxidone or MS Contin or Norco or Opana ER or OxyContin or Oxycet or OxyNEO or Oxycocet or Palladone or Percocet or Percodan or Reprexain or Rezira or Roxicet or Roxicodone or Targiniq ER or TussiCaps or Tussionex or Tuzistra XR or Tylenol or Vicodin or Vicodin ES or Vicodin HP or Vicoprofen or Vituz or Xartemis XR or Xodol or Zolvit or Zutripro or Zydone).ti,ab. (713) 28 ("poly?substance use" or "poly?drug use").ti,ab. (1267) 29 Drug Overdose/(11,794) 30 "Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions"/(32,743) 31 mortality/or "cause of death"/or fatal outcome/or hospital mortality/(191,882) 32 (poisoning or overdose or toxic or toxicity or death* or mortality or mortalities or fatal*).ti,ab. (2,114,367) 33 (emergency or emergencies or hospitalization or hospitalisation).ti,ab. (409,654) 34 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 (230,234) 35 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 (2,515,891) 36 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 (1,992,812) 37 (North America or America or Canada or Canadian or American or United States or USA or Australia or UK or United Kingdom or England or Wales or Scotland or Mexico or Alberta or British Columbia or Manitoba or New Brunswick or Newfoundland or Northwest Territories or Nova Scotia or Nunavut or Ontario or Prince Edward Island or Quebec or Saskatchewan or Yukon or Alabama or Alaska or Arizona or Arkansas or California or Colorado or Connecticut or Delaware or Florida or Georgia or Hawaii or Idaho or Illinois or Indiana or Iowa or Kansas or Kentucky or Louisiana or Maine or Maryland or Massachusetts or Michigan or Minnesota or Mississippi or Missouri or Montana or Nebraska or Nevada or New Hampshire or New Jersey or New Mexico or New York or North Carolina or North Dakota or Ohio or Oklahoma or Oregon or Pennsylvania or Rhode Island or South Carolina or South Dakota or Tennessee or Texas or Utah or Vermont or Virginia or Washington or West Virginia or Wisconsin or Wyoming or American Samoa or Guam or Northern Mariana Islands or Puerto Rico or Virgin Islands).ti,ab. (1,438,245) 38 (Andorra or Austria or Balkan Peninsula or Belgium or Albania or Bosnia or Bulgaria or Croatia or Czech Republic or Hungary or Kosovo or Macedonia or Moldova or Montenegro or Poland or Belarus or Romania or Russia or Serbia or Slovakia or Slovenia or Ukraine or France or Germany or Gibraltar or Greece or Ireland or Italy or Liechtenstein or Luxembourg or Mediterranean Region or Monaco or Netherlands or Portugal or San Marino or Denmark or Finland or Iceland or Norway or Sweden or Spain or Switzerland or Armenia or Azerbaijan or Ireland or Armenia or Georgia or Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan or Moldova or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vatican City).ti,ab. (584,214) 39 37 or 38 (1,953,198) 40 (determinant* or predictor* or factor* or correlate*).ti,ab. (4,644,515) 41 36 or 40 (6,136,388) 42 34 and 35 and 39 and 41 (2191) 43 limit 42 to (English language and humans and yr = "2000 -Current") (1492) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Draanen, J., Tsang, C., Mitra, S. et al. Mental disorder and opioid overdose: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57, 647–671 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02199-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02199-2