Abstract

Purpose

The war in Syria has created the greatest refugee crisis in the twenty-first century. Turkey hosts the highest number of registered Syrian refugees, who are at increased risk of common mental disorders because of their exposure to war, violence and post-displacement stressors. The aim of this paper is to examine the prevalence and predictors of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of adult Syrian refugees was conducted between February and May 2018 in Istanbul (Sultanbeyli district). Participants (N = 1678) were randomly selected through the registration system of the district municipality. The Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25) was used to measure anxiety and depression and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist (PCL-5) assessed posttraumatic stress. Descriptive and multivariate regression analyses were used.

Results

The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety, depression and PTSD were 36.1%, 34.7% and 19.6%, respectively. Comorbidity was high. Regression analyses identified several socio-demographic, health and post-displacement variables that predicted common mental disorders including: being female, facing economic difficulties, previous trauma experience, and unmet need for social support, safety, law and justice. A lifetime history of mental health treatment and problems accessing adequate healthcare were associated with depression and anxiety but not with PTSD.

Conclusions

Mental disorder symptoms are highly prevalent among Syrian refugees in Turkey. The association with post-displacement factors points to the importance of comprehensive health and social services that can address these social, economic and cultural stressors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data

Further information on the data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from Daniela Fuhr or Bayard Roberts (e-mail address:Daniela.fuhr@lshtm.ac.uk or bayard.roberts@lshtm.ac.uk).

References

UNHCR (2018) Global trends forced displacement in 2018

UNHCR (2019) Operational Portal: Refugee Situation. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria

UNHCR (2019) Figures at a Glance. https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

Republic of Turkey DGoMM Temporary Protection Istatistics (2019) https://www.goc.gov.tr/gecici-koruma5638

Georgiadou E, Zbidat A, Schmitt GM, Erim Y (2018) Prevalence of mental distress among Syrian refugees with residence permission in Germany: a registry-based study. Front Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00393

Ben Farhat J, Blanchet K, Juul Bjertrup P et al (2018) Syrian refugees in Greece: experience with violence, mental health status, and access to information during the journey and while in Greece. BMC Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1028-4

Chen W, Hall BJ, Ling L, Renzaho AM (2017) Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30032-9

Kartal D, Kiropoulos L (2016) Effects of acculturative stress on PTSD, depressive, and anxiety symptoms among refugees resettled in Australia and Austria. Eur J Psychotraumatol. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.28711

Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A et al (2019) New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30934-1

Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J (2005) Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6

Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D et al (2009) Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA J Am Med, Assoc

Turrini G, Purgato M, Ballette F et al (2017) Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. Int J Ment Health Syst. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-017-0156-0

Morina N, Akhtar A, Barth J, Schnyder U (2018) Psychiatric disorders in refugees and internally displaced persons after forced displacement: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 9:433

Schick M, Morina N, Mistridis P et al (2018) Changes in post-migration living difficulties predict treatment outcome in traumatized refugees. Front Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00476

Miller KE, Rasmussen A (2017) The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: an ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000172

Jordans MJD, Semrau M, Thornicroft G, Van Ommeren M (2012) Role of current perceived needs in explaining the association between past trauma exposure and distress in humanitarian settings in Jordan and Nepal. Br J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.102137

Tinghög P, Malm A, Arwidson C et al (2017) Prevalence of mental ill health, traumas and postmigration stress among refugees from Syria resettled in Sweden after 2011: a population-based survey. BMJ Open 7:e018899

Nickerson A, Schick M, Schnyder U et al (2017) Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in tortured, treatment-seeking refugees. J Trauma Stress. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22205

Satinsky E, Fuhr DC, Woodward A et al (2019) Mental health care utilisation and access among refugees and asylum seekers in Europe: a systematic review. Health Policy (N Y). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.02.007

Hendrickx M, Woodward A, Fuhr D, Sondorp E RB (2019) The burden of mental disorders and access to mental health and psychosocial support services in Syria and among Syrian refugees in neighbouring countries: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health

Fuhr DC, Acarturk C, McGrath M, Ilkkursun Z, Woodward A, Sondorp E, Sijbrandij M, Cuipers P, Roberts B (2020) Treatment gap and mental health service use among Syrian refugees in Turkey: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000660

Elicin Y (2018) refugee crisis and local responses: an assessment of local capacities to deal with migration influxes in Istanbul. Croat Comp PUBLIC Adm 18:73–99

Erdoğan M (2017) 6. Yılında Türkiye’deki Suriyeliler: Sultanbeyli Örneği. http://panel.stgm.org.tr/vera/app/var/files/6/-/6-yilinda-turkiyedeki-suriyeliler-sultanbeyli-ornegi.pdf

Asgari Ücret Tespit Komisyonu Kararı (2016) TC Resmi Gazate. https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2016/12/20161230-22.pdf

World Health Organization & King’s College London (2011) The Humanitarian Emergency Settings Perceived Needs Scale (HESPER): Manual with Scale. Geneva: World Health Organization

Kleijn WC, Hovens JE, Rodenburg JJ (2001) Posttraumatic stress symptoms in refugees: assessments with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Hopkins symptom checklist-25 in different languages. Psychol Rep. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2001.88.2.527

Mahfoud Z, Kobeissi L, Peters TJ et al (2013) The Arabic Validation of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25 against MINI in a Disadvantaged Suburb of Beirut, Lebanon. Int J Educ Psychol Assess 2013:1–8

Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW et al (2016) Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscipl J. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Raykov T (1997) Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Appl Psychol Measur. https://doi.org/10.1177/01466216970212006

StataCorp (2015) Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station

Schober P, Schwarte LA (2018) Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth Analg. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864

Acarturk C, Cetinkaya M, Senay I et al (2018) Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms among syrian refugees in a refugee camp. J Nerv Ment Dis. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000693

Poole DN, Hedt-Gauthier B, Liao S et al (2018) Major depressive disorder prevalence and risk factors among Syrian asylum seekers in Greece. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5822-x

Alpak G, Unal A, Bulbul F et al (2015) Post-traumatic stress disorder among Syrian refugees in Turkey: a cross-sectional study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2014.961930

Chung MC, AlQarni N, AlMazrouei M et al (2018) Posttraumatic stress disorder and psychiatric co-morbidity among Syrian refugees of different ages: the role of trauma centrality. Psychiatr Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-018-9586-3

Porter M, Haslam N (2005) Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. J Am Med, Assoc

Schubert CC, Punamäki RL (2011) Mental health among torture survivors: cultural background, refugee status and gender. Nord J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2010.514943

Song SJ, Subica A, Kaplan C et al (2018) Predicting the mental health and functioning of torture survivors. J Nerv Ment Dis. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000678

Schweitzer RD, Vromans L, Brough M et al (2018) Recently resettled refugee women-at-risk in Australia evidence high levels of psychiatric symptoms: individual, trauma and post-migration factors predict outcomes. BMC Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1143-2

Hassan G, Ventevogel P, Jefee-Bahloul H et al (2016) Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000044

Boswall K, Al Akash R (2015) Personal perspectives of protracted displacement: an ethnographic insight into the isolation and coping mechanisms of Syrian women and girls living as urban refugees in northern Jordan. Intervention. https://doi.org/10.1097/WTF.0000000000000097

Wringe A, Yankah E, Parks T et al (2019) Altered social trajectories and risks of violence among young Syrian women seeking refuge in Turkey: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0710-9

Chu T, Keller AS, Rasmussen A (2013) Effects of post-migration factors on PTSD outcomes among immigrant survivors of political violence. J Immigr Minor Heal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9696-1

Simich L, Hamilton H, Baya BK (2006) Mental distress, economic hardship and expectations of life in Canada among sudanese newcomers. Transcult Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461506066985

Steel Z, Silove D, Brooks R et al (2006) Impact of immigration detention and temporary protection on the mental health of refugees. Br J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007864

Riley A, Varner A, Ventevogel P et al (2017) Daily stressors, trauma exposure, and mental health among stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Transcult Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461517705571

Gammouh OS, Al-Smadi AM, Tawalbeh LI, Khoury LS (2015) Chronic diseases, lack of medications, and depression among syrian refugees in Jordan, 2013-2014. Prev, Chronic Dis

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S et al (2007) No health without mental health. Lancet 370:859–877

Mulugeta W, Xue H, Glick M et al (2019) Burden of mental illness and non-communicable diseases and risk factors for mental illness among refugees in Buffalo, NY, 2004–2014. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0498-6

Javanbakht A, Rosenberg D, Haddad L, Arfken CL (2018) Mental health in Syrian refugee children resettling in the United States: war trauma, migration, and the role of parental stress. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57:209–211

Acknowledgements

Electronic data solutions were provided by LSHTM Open Data Kit (odk.lshtm.ac.uk).

Funding

This study was funded through the STRENGTHS (Syrian REfuGees MeNTal HealTH Care Systems) project. The STRENGTHS project is funded under Horizon 2020—the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2014–2020) (Grant no. 733337). The content of this article reflects only the authors’ views and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

CA wrote the first draft of the report and was responsible for overseeing data collection in Turkey. DF and BR designed the survey and were involved in data management. MMG statistically analysed the data. ZI, PC, MS, EG, PV, and MMK contributed to the interpretation of data and critically revised the paper. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix A

The sample size was determined to meet the broader aims of the overall study (rather than this specific paper). This included desire to analyze a sample sub-group of those seeking mental health care (reported elsewhere). To determine adequate sample size for the overall study, the following calculation was made:

n number of people in one group, s standard deviation, c 7.85 (for 80% power and 5% significance level), d size of the difference to be detected (0.8 SD).

Precise estimates of levels of mental disorders and associated factors could not be determined due to the limited reliable data on mental health among Syrian refugees in Turkey. Therefore, to ensure adequate power to detect conceptually important differences within a multivariate analysis, the following parameters and calculations were used: power = 80%; significance level = 5%; conceptually important difference in outcome scores = 0.8 standard deviation (by convention a ‘large’ difference) (Cohen 1988); size of ‘rarest’ sub-group of respondents we would attempt to include in our analysis = 5%; expected proportion of unusable questionnaires = 10%.

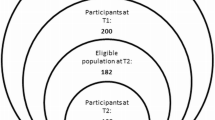

Using these parameters, a sample size of 314 was required to detect a difference when only 5% of the population falls into a particular sub-group of interest. Within this group, we assumed approximately 25% will have used health services (based on findings of studies with other conflict-affected populations). Therefore, the minimum sample size required is 1444, including a 15% incompletion rate. For the sampling process, we assumed around a 50% response rate and so selected 2,865 names of Syrian refugees from the Sultanbeyli municipal registry and 1,678 (59%) participated. As a result, we were slightly above the minimum sample size required.

References:

Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum.

Appendix B

Variable | PCL-5 score (PTSD) (n = 1345) | HSCL-25 (depression) (n = 1355) | HSCL-25 (anxiety) (n = 1355) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

Female | 3.46 | 0.67 | 0.13*** | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.20*** | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.25*** |

Age (years) | − 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.02 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.06** | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.02 |

Education (years) | 0.07 | 0.89 | 0.02 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.00 | − 0.01 | 0.00 | − 0.05* |

Number of years displaced | − 0.27 | 0.28 | − 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

Number of years living in Sultanbeyli | − 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.03 | − 0.03 | 0.02 | − 0.06 | − 0.03 | 0.02 | − 0.06 |

Household economic situation (ref = Bad) | |||||||||

Average | − 3.90 | 0.67 | − 0.14*** | − 0.26 | 0.33 | − 0.19*** | − 0.20 | 0.03 | − 0.15*** |

Good or very good | − 7.85 | 1.66 | − 0.12*** | − 0.53 | 0.08 | − 0.16*** | − 0.41 | 0.08 | − 0.12*** |

Long-term illness or disability | 3.10 | 0.72 | 0.11*** | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.11*** | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.13*** |

Lifetime history of mental health treatment | 4.02 | 1.04 | 0.92*** | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.09*** | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.12*** |

Unable to access adequate healthcare | 2.12 | 0.75 | 0.07** | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.08** | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.08** |

You or your family not safe and protected | 4.97 | 1.16 | 0.11*** | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.09*** | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.09*** |

Problems in your community with law & justice | 5.03 | 0.88 | 0.15*** | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.07** | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.07** |

Not enough emotional support from others | 3.47 | 0.73 | 0.12*** | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.13*** | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.14*** |

Experienced a potentially traumatic event | 6.47 | 0.68 | 0.24*** | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.17*** | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.16*** |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Acarturk, C., McGrath, M., Roberts, B. et al. Prevalence and predictors of common mental disorders among Syrian refugees in Istanbul, Turkey: a cross-sectional study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 475–484 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01941-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01941-6