Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Diabetic foot disease (DFD) is a leading cause of hospital admissions and amputations. Global trends in diabetes-related amputations have been previously reviewed, but trends in hospital admissions for multiple other DFD conditions have not. This review analysed the published incidence of hospital admissions for DFD conditions (ulceration, infection, peripheral artery disease [PAD], neuropathy) and diabetes-related amputations (minor and major) in nationally representative populations.

Methods

PubMed and Embase were searched for peer-reviewed publications between 1 January 2001 and 5 May 2022 using the terms ‘diabetes’, ‘DFD’, ‘amputation’, ‘incidence’ and ‘nation’. Search results were screened and publications reporting the incidence of hospital admissions for a DFD condition or a diabetes-related amputation among a population representative of a country were included. Key data were extracted from included publications and initial rates, end rates and relative trends over time summarised using medians (ranges).

Results

Of 2527 publications identified, 71 met the eligibility criteria, reporting admission rates for 27 countries (93% high-income countries). Of the included publications, 14 reported on DFD and 66 reported on amputation (nine reported both). The median (range) incidence of admissions per 1000 person-years with diabetes was 16.3 (8.4–36.6) for DFD conditions (5.1 [1.3–7.6] for ulceration; 5.6 [3.8–9.0] for infection; 2.5 [0.9–3.1] for PAD) and 3.1 (1.4–10.3) for amputations (1.2 [0.2–4.2] for major; 1.6 [0.3–4.3] for minor). The proportions of the reported populations with decreasing, stable and increasing admission trends were 80%, 20% and 0% for DFD conditions (50%, 0% and 50% for ulceration; 50%, 17% and 33% for infection; 67%, 0% and 33% for PAD) and 80%, 7% and 13% for amputations (80%, 17% and 3% for major; 52%, 15% and 33% for minor), respectively.

Conclusions/interpretation

These findings suggest that hospital admission rates for all DFD conditions are considerably higher than those for amputations alone and, thus, the more common practice of reporting admission rates only for amputations may substantially underestimate the burden of DFD. While major amputation rates appear to be largely decreasing, this is not the case for hospital admissions for DFD conditions or minor amputation in many populations. However, true global conclusions are limited because of a lack of consistent definitions used to identify admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations, alongside a lack of data from low- and middle-income countries. We recommend that these areas are addressed in future studies.

Registration

This review was registered in the Open Science Framework database (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4TZFJ).

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes is now the eighth leading, and most rapidly growing, cause of the global disease burden [1, 2]. Diabetes-related foot disease (DFD) is the leading cause of the diabetes disability burden [3,4,5]. DFD is defined by ulceration, infection or other destructive conditions of the foot in people with diabetes and is precipitated by the risk factors peripheral neuropathy and peripheral artery disease (PAD) [6, 7]. DFD takes months to heal, is intensive to treat and places people at high risk of hospital admission and amputation [8,9,10,11]. It has been estimated that 20 million people worldwide have DFD, with a further 130 million having a key risk factor for DFD, resulting in around nine million hospital admissions and 2 million amputations each year [3,4,5, 9].

DFD has long been known to be the leading cause of amputations [3,4,5]. For this reason, and because data on amputation procedures are relatively easily and reliably collected [12,13,14], the incidence of hospital admissions in which an amputation procedure has occurred has been used as the primary measure to monitor DFD burden [15,16,17]. Previous reviews have suggested that trends in the incidence of admissions for diabetes-related major amputations (above ankle) are decreasing over time, whereas admissions for minor amputations (below ankle) are increasing over time [15,16,17]. These previous reviews infer that DFD care must be improving, with hospital treatments such as minor amputation procedures more commonly achieving limb salvage and reductions in major amputation admissions [12,13,14]. However, these reviews have investigated admissions for amputations only [15, 16] and not considered any of the multiple other DFD conditions such as ulceration or infection. Furthermore, the last review to primarily investigate global amputation trends was published over a decade ago [17].

Amputations are now performed in a minority of people admitted to hospital for treatment of DFD, because other treatments such as antibiotics and revascularisation are being used more effectively to salvage limbs [5, 9, 18, 19]. However, DFD has recently been reported as a leading and growing cause of all hospital admissions in high-income countries [8,9,10, 18]. As most hospital admissions for DFD are now unrelated to amputation, the burden of DFD may be better assessed through hospital admission rates for all DFD conditions, in line with methods used to monitor other diseases [20,21,22,23]. The primary aim of this review was to synthesise the findings from peer-reviewed publications reporting the incidence of hospital admissions for DFD conditions or for diabetes-related amputations in nationally representative populations. Secondary aims included reviewing the incidence of or trends in hospital admissions for different classification groups, including DFD condition, amputation procedure, age, sex, diabetes type and country.

Methods

For this narrative review, we systematically searched PubMed and Embase to identify peer-reviewed publications reporting the incidence, or trends in the incidence, of hospital admissions for DFD conditions or diabetes-related amputation procedures in nationally representative populations between 1 January 2001 and 5 May 2022. This period was selected as it followed the publication of the first practice guidelines by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) in 1996, which is likely to have substantially changed international practice [19]. We used search strings combining keywords for DFD conditions OR amputation procedures, incidence OR trend AND nation OR country (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Tables 1 and 2), which had been shown to identify ten key eligible publications [3, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. This review was registered in the Open Science Framework database (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4TZFJ).

Eligible publications were those reporting the incidence of hospital admissions for DFD conditions or diabetes-related amputations among a population considered representative of a country. Hospital admission for a DFD condition was defined as admission of a person with diabetes as an inpatient with a principal (primary reason for the admission) or additional (secondary reason for the admission) diagnosis of a DFD condition [9, 32]. A DFD condition was defined as ulceration, infection, PAD or neuropathy of the foot or lower extremity in a person with diabetes [6, 7]. An amputation was defined as any resection of a lower extremity through a bone or joint during a hospital admission of a person with diabetes. Amputations were categorised as major (proximal to the ankle) or minor (through or distal to the ankle) [6, 7]. Incidence rates in this review are reported for principal or any (principal or additional diagnosis) admissions for total DFD conditions combined (where publications reported aggregated admissions for DFD conditions, including ulceration and infection as a minimum) or for ulceration, infection, PAD or neuropathy separately (where publications reported these conditions separately). Incidence rates are also reported for hospital admissions for all amputations combined (where publications reported aggregated admissions for major and minor amputations) and for major and minor amputations separately (when reported separately). In this review, unless otherwise indicated, reported outcomes refer only to the primary DFD condition or highest-level amputation procedure that was investigated for each admission. We considered a nationally representative population as one that captures outcomes for at least 50% of the country’s population with diabetes, or at least 50% of a country’s resident population (i.e. the total population of all citizens of the country, with or without diabetes), or as one defined as a nationally representative sample according to the publication [16, 33]. Countries were categorised according to the World Bank income classification into high-, middle- or low-income countries [34].

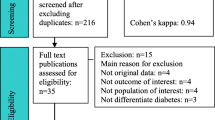

Titles and abstracts identified in the searches were screened using the eligibility criteria by one author (PAL) and the full texts of eligible publications were retrieved and assessed for final inclusion by the same author. Relevant reviews identified in the searches and reference lists of included publications were also manually searched to identify additional eligible publications. Data were extracted from included publications into evidence tables by one author (PAL) and samples of extracted data were serially checked by another author (SMC) until no errors were found. Data extracted included country, study reference, aims, years of data collected, data sources, type of population, type of incidence, initial rate (the first incidence rate for the time period reported by the publication), end rate (the last incidence rate for the time period reported by the publication), relative trend over time (calculated descriptively as the percentage change between the initial rate and the end rate for the period reported) and p value if reported. Publications reporting similarly defined incidence rates were descriptively summarised using medians (ranges: min. value, max. value reported) for initial rates, end rates and relative trends. For ease of reporting results, we descriptively defined a decreasing trend as a >5% decrease in relative trend, an increasing trend as a >5% increase in relative trend and a stable trend as a ≤5% relative trend in either direction; however, these rates do not infer statistical significance.

Results

A total of 3990 records were identified as relevant from the initial searches, resulting in 2527 unique records after duplicate removal. After title and abstract screening, 117 publications were deemed eligible for full-text assessment, with 57 ultimately included after full-text review. Further manual searching identified another 14 publications for inclusion, leading to 71 publications being included in this review. Of these 71 publications, 14 (20%) reported on admissions for DFD conditions and 66 (93%) on admissions for amputations (nine [13%] reported both). Table 1 summarises the main findings of these publications.

DFD conditions

We found 14 publications reporting the incidence rates of hospital admissions for DFD conditions (Table 2, ESM Table 3). Four publications reported incidence rates for total DFD conditions combined, seven reported rates for ulceration, three reported rates for infection and four reported rates for PAD. No publications reported incidence rates for neuropathy. Of the 14 publications, 13 (93%) reported rates using the population with diabetes as a denominator and two (14%) reported rates among the resident population (one [7%] reported both). All reported rates for high-income countries, including three Asian countries, two European countries, two North American countries and one Western Pacific country. Population denominators were identified from national health insurance databases (57%), national diabetes registries (21%), national diabetes prevalence surveys applied to national census databases (14%) and national census databases (7%). All publications identified incidence of admission for DFD condition numerators using ICD diagnosis codes (50% used ICD-9 [http://www.icd9data.com/2007/Volume1/default.htm] and 50% used ICD-10 [http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en] diagnosis codes) from national health insurance databases (57%), national hospital discharge databases (36%) or national inpatient samples (7%). All publications reported a mutually exclusive incidence of admission for a DFD condition, with 36% of publications reporting only principal admissions where the principal diagnosis code for the admission was a DFD condition and the rest (64%) reporting admissions where any (principal or additional) diagnosis code for the admission was a DFD condition. Incidence rates were mostly reported as age-adjusted estimates, which were standardised to national or regional populations (64%) or the population studied (21%), with the remainder reported as crude incidence rates (14%).

Total DFD

Four publications reported admission rates for total DFD conditions combined, in six different populations, with trends over time reported in all (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1). Principal admissions were reported in four of these populations (including one in a resident population) and any admissions in two populations. The median (range) initial rate in the five diabetes populations was 16.3 (8.4, 36.6) per 1000 person-years with diabetes and the median (range) end rate was 12.2 (6.4, 20.9). The median (range) relative trend was –24% (–43%, –4%), with trends in four (80%) of the five populations decreasing and the trend stable in one (20%) population. Comparing principal admission rates with any admission rates, the initial rate was similar, the end rate for principal admission rates was lower and the trend for principal admission rates was greater (16.3, 10.5, –24% vs 17.1, 16.1, –7%, respectively).

National trends since 2001 in hospital admission rates for DFD conditions per 1000 person-years with diabetes. When rates are limited to specific ages, these are shown in years in brackets. Total: total admissions for DFD conditions, typically including total aggregated admissions for diabetes-related foot ulcers, infections, PAD and neuropathy. Ulceration: admissions for diabetes-related foot ulceration, typically including ulcers of the foot, ankle or lower leg. Infection: admissions for diabetes-related foot infection, typically including cellulitis and osteomyelitis. PAD: admissions for diabetes-related PAD, typically including PAD diagnosis or peripheral revascularisation procedures. Data are from population-based studies reporting age-standardised incidence rates of hospital admissions for DFD conditions in national populations with diabetes over time. The figure is intended to aid interpretation of relative trends over time between reported initial and end rates; it is not reflective of exact annual trends and should not be used to compare rates between countries, as publications may have used different definitions for diagnosis of diabetes and DFD conditions. If multiple publications from the same country for the same condition were identified, only the publication with the most recent years of data was included; if multiple publications included the same years of data, the publication covering more of the population or condition was favoured (e.g. lower extremity infection was favoured over foot infection). aUnadjusted rate. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

Ulceration

Seven publications reported admission rates for ulceration conditions, in eight populations, with trends reported in four (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1). Principal admissions were reported in three diabetes populations and any admissions in five (including one in a resident population). The median (range) initial rate in the seven diabetes populations was 5.1 (1.3, 7.6) per 1000 person-years with diabetes and the median (range) end rate was 4.3 (0.6, 7.0). The median (range) relative trend was –7% (–55%, +38%), with trends decreasing in two (50%) and increasing in two (50%) of the populations studied.

Infection

Three publications reported admission rates for infection conditions, in six populations, with trends reported in all (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1). All reported principal admissions. The median (range) initial rate was 5.6 (3.8, 9.0) per 1000 person-years with diabetes and the median (range) end rate was 5.1 (2.0, 6.8). The median (range) relative trend was –15% (–57%, +30%), with trends decreasing in three (50%), stable in one (17%) and increasing in two (33%) populations.

PAD

Four publications reported admission rates for PAD conditions, in six populations, with trends reported in three (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1). Principal and any admissions were reported in three populations each. The median (range) initial rate was 2.5 (0.9, 3.1) per 1000 person-years with diabetes and the median (range) end rate was 0.7 (0.4, 4.6). The median (range) relative trend was –6% (–76%, +64%), with trends decreasing in two (67%) populations and increasing in one (33%) population.

Amputations

We found 66 publications reporting the rates of admissions for amputation, including 42 reporting total, 39 reporting major and 27 reporting minor amputations (Tables 1 and 3–5, ESM Table 4). Of the 66 publications, most (80%) reported rates using the population with diabetes as the denominator, with the remainder (20%) reporting rates among residents. Nearly all (92%) reported rates for high-income countries, with the rest (8%) reporting rates for middle-income countries. No publications reported rates for low-income countries. Sixteen European, five Asian, three Western Pacific and three North American countries were included, with four publications reporting rates for up to 31 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Population denominators were identified from national health insurance databases (32%), national diabetes prevalence surveys applied to national census databases (29%), national diabetes registries (20%) or national census databases (20%). Amputation incidence numerators were identified using procedural codes in national hospital discharge databases (80%), national inpatient samples (9%), national health insurance databases (8%) or national surgical theatre records (3%). All publications reported a mutually exclusive incidence of admission for the highest amputation level that occurred in the admission, with 68% including amputation procedures of any cause in people with diabetes and the rest (32%) excluding those caused by trauma or malignancy. Incidence rates were mostly reported as age-adjusted estimates, which were standardised to national or regional populations (48%) or the population studied (18%), with the remainder reported as crude incidence rates (33%).

Total amputations

We found 42 publications reporting admission rates for total diabetes-related amputations. In total, 35 reported rates among populations with diabetes and 12 reported rates among resident populations (with four reporting on both) (Table 3). Of the 35 publications reporting rates in 40 different populations with diabetes, 26 reported trends over time in 30 different populations (Tables 1 and 3). The median (range) initial rate was 3.1 (1.4, 10.3) total amputation admissions per 1000 person-years with diabetes and the median (range) end rate was 2.5 (0.6, 7.8). The median (range) relative trend was –27% (–73%, +25%), with trends in 24 (80%) of the 30 populations decreasing, trends in two (7%) stable and trends in four (13%) increasing. In four publications primarily reporting rates stratified by sex, male populations had greater initial and end rates, but the relative trend over time was similar in male and female populations (6.2, 4.1, –50% vs 3.6, 2.0, –51%, respectively) (Table 3).

Of the 12 publications reporting rates in 14 different resident populations (residents with or without diabetes), trends over time were reported for ten populations (Table 3). The median (range) initial rate was 0.155 (0.088, 2.700) total diabetes-related amputation admissions per 1000 residents and the median (range) end rate was 0.135 (0.050, 0.255). The median (range) relative trend was –17% (–44%, +40%), with trends in seven (70%) of the ten populations decreasing and trends in three (30%) increasing. One publication reported rates for 26 OECD member countries, including a mean initial rate of 0.132 total diabetes-related amputation (excluding toe) admissions per 1000 adult residents and a mean end rate of 0.078. Of trends reported for 24 of the countries, the mean relative trend was –41%, with trends in 14 (58%) of the 24 countries decreasing, trends in five (21%) stable and trends in five (21%) increasing [28].

Major amputations

We found 39 publications reporting admission rates for major diabetes-related amputation, including 31 reporting rates among populations with diabetes and 12 reporting rates among resident populations (with four reporting both) (Table 4). Of the 31 publications reporting rates in 36 populations with diabetes, 25 reported trends over time in 30 populations (Tables 1 and 4, Fig. 2a,b). The median (range) initial rate was 1.2 (0.2, 4.2) major amputation admissions per 1000 person-years with diabetes and the median (range) end rate was 0.9 (0.2, 1.8). The median (range) relative trend was –35% (–91%, +10%), with trends in 24 (80%) of the 30 populations decreasing, trends in five (17%) stable and trends in one (3%) increasing.

National trends since 2001 in hospital admission rates for major amputations per 1000 person-years with diabetes in (a) all ages and (b) adults by country. Data are from population-based studies reporting age-standardised incidence rates of hospital admissions for major amputation in national populations with diabetes over time. The figure is intended to aid interpretation of relative trends over time between reported initial and end rates; it is not reflective of exact annual trends and should not be used to compare rates between countries, as publications may have used different definitions for diagnosis of diabetes and amputation procedures. If multiple publications from the same country were identified, only the publication with the most recent years of data was included; if multiple publications included the same years of data, the publication covering more of the population was favoured (e.g. type 2 diabetes was favoured over type 1 diabetes). aIncludes only the first amputation; bunadjusted rate. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

Of the 12 publications reporting rates in 14 resident populations, trends over time were reported for nine populations (Table 4). The median (range) initial rate was 0.069 (0.005, 1.030) major diabetes-related amputation admissions per 1000 residents and the median (range) end rate was 0.064 (0.002, 0.092). The median (range) relative trend was –26% (–69%, +42%), with trends in seven (78%) populations decreasing, trends in one (11%) increasing and trends in one (11%) stable. One publication reported rates for 31 OECD member countries, including a mean initial rate of 0.074 per 1000 adult residents and a mean end rate of 0.064. Of trends reported for 29 of these countries, the mean relative trend was –14%, with trends in 17 (59%) countries decreasing, trends in seven (24%) stable and trends in five (17%) increasing [21].

Minor amputations

We found 27 publications reporting admission rates for minor diabetes-related amputations, including 25 reporting rates among populations with diabetes and six reporting rates among resident populations (with four reporting both) (Table 5). Of the 25 publications reporting rates in 30 populations with diabetes, 22 reported trends over time in 27 populations (Tables 1 and 5, Fig. 3a,b). The median (range) initial rate was 1.6 (0.3, 4.3) minor amputation admissions per 1000 person-years with diabetes and the median (range) end rate was 1.4 (0.3, 3.8). The median (range) relative trend was –13% (–59%, +49%), with trends in 14 (52%) of the 27 populations decreasing, trends in four (15%) stable and trends in nine (33%) increasing.

National trends since 2001 in hospital admission rates for minor amputations per 1000 person-years with diabetes in (a) all ages and (b) adults by country. Data are from population-based studies reporting age-standardised incidence rates of hospital admissions for minor amputation in national populations with diabetes over time. The figure is intended to aid interpretation of relative trends over time between reported initial and end rates; it is not reflective of exact annual trends and should not be used to compare rates between countries, as publications may have used different definitions for diagnosis of diabetes and amputation procedures. If multiple publications from the same country were identified, only the publication with the most recent years of data was included; if multiple publications included the same years of data, the publication covering more of the population was favoured (e.g. type 2 diabetes was favoured over type 1). aIncludes only the first amputation; bunadjusted rate. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

Of the six publications reporting rates in seven resident populations, trends over time were reported for six populations (Table 5). The median (range) initial rate was 0.092 (0.009, 0.123) minor diabetes-related amputation admissions per 1000 residents and the median (range) end rate was 0.098 (0.005, 0.274). The median (range) relative trend was +11% (–49%, +88%), with trends in two (33%) populations decreasing, trends in one (17%) stable and trends in three (50%) increasing.

Discussion

This narrative review analysed findings from 71 eligible publications on hospital admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations in national populations. The findings suggest that national hospital admission rates are substantially higher for DFD than for amputation alone. Trends in admission rates for major amputations are largely decreasing, but trends for minor amputations are inconsistent, decreasing in some countries but increasing in others. Trends in admission rates for DFD conditions are also inconsistent and reported in far fewer publications than for amputations. Although all publications reported the incidence of admissions exclusively for a condition or procedure or set of conditions or procedures, which helps avoid overestimation, there was a high level of heterogeneity in the methods employed to identify admissions and populations. While this review provides the most comprehensive global picture to date on hospital admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations, the conclusions are limited by this heterogeneity and the lack of publications from low- and middle-income countries.

Hospital admissions for DFD conditions

Unlike hospital admission rates for amputations and other diabetes complications [20,21,22,23], hospital admission rates for DFD conditions have only recently begun being used as an outcome for monitoring the burden of DFD [8,9,10, 18]. To our knowledge, this is the first review that has focused on hospital admissions for DFD conditions. The median initial admission rate for a principal or any diagnosis of total DFD conditions was 16.3 per 1000 person-years with diabetes, based on findings from only four publications [32, 35,36,37]. This rate is in keeping with the aggregated median initial admission rates found across ten additional publications on individual DFD conditions, including 5.1 for ulceration, 5.6 for infection and 2.5 for PAD (Tables 1 and 2). However, trend patterns differed, with principal admission rates for total DFD conditions largely decreasing in most populations, but increasing or decreasing for individual DFD conditions, suggesting that admission rates for some individual DFD conditions are decreasing more rapidly than rates for others are increasing.

These indicative findings of high principal admission rates for DFD conditions should, however, be of immediate concern. We can relatively safely assume that these admissions were primarily caused by DFD conditions. The principal admission rates found for DFD conditions in this review are at least equivalent to rates reported for other major diabetes complications [16, 23, 35, 37,38,39]. This supports recent studies suggesting that DFD is a leading cause of diabetes-related hospital admissions in high-income countries [8, 9, 18, 33]. Further, we reviewed hospital admission incidence and not length of hospital stay, which is often used as a measure of condition severity [7]. With DFD also known to result in comparatively long hospital stays, these results are perhaps even more concerning [22, 40, 41].

However, because of the limited number of publications identified, the high level of heterogeneity in hospital diagnosis coding criteria used to identify admissions, including the use of principal or any diagnosis codes and ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis codes, and the different DFD conditions investigated, more research is needed to confirm the high rates and decreasing trends seen for principal admissions for DFD conditions. Ideally, globally recognised standardised and validated ICD coding sets should be developed. In addition, we suggest that admission rates for both DFD conditions and amputations should be reported in future global and national reports of trends in the incidence of diabetes complications [21, 28, 42].

Hospital admissions for amputations

To our knowledge, this is the largest review to date of hospital admission rates for amputation in terms of publications reviewed [15,16,17] and the first in over a decade to primarily investigate global trends in diabetes-related amputations [17]. In this review of mostly 21st century rates, we found a median initial rate of hospital admission for total amputations of 3.1 per 1000 person-years with diabetes (Tables 1 and 3), which is lower than the rate of 5.9 found in the previous global review, which reported mostly 20th century rates [17]. Although most publications included in this review reported total amputation rates, this outcome is no longer recommended; instead, it is recommended that major and minor amputation rates are reported separately, as they are performed for different clinical reasons [14, 16, 42].

For major amputation, we found a median initial hospital admission rate of 1.2 per 1000 person-years with diabetes (Tables 1 and 4), which is lower than the rate of 2.3 found in the previous review [17]. Similar to other reviews [15,16,17], we found decreasing trends in major amputation rates over time among most (80%) populations studied. This may suggest that there have been gradual improvements in DFD care globally. However, given that most publications did not report nationwide improvements in DFD care and the inconsistent trends found in the only publication that reported rates for multiple (OECD) countries [21], these findings may equally reflect changes in general diabetes care, differing methods used to diagnose and define the population with diabetes over time, resulting in more rapid increases in the sizes of populations with diabetes used as denominators [43], or selection bias in countries potentially ‘self-reporting’ favourable trends. Thus, further regular standardised reporting of major amputation rate trends across multiple countries is required, such as that undertaken by OECD countries, to better understand trends over time [21, 28, 42].

For minor amputation, we found a median initial hospital admission rate of 1.6 per 1000 person-years with diabetes (Tables 1 and 5), which was higher than the rate of 1.2 found in the previous review [17]. In contrast to other reviews [15,16,17], we found inconsistent trends in minor amputation rates over time among the populations studied (52% decreasing, 33% increasing, 15% stable). Further, we found that only 14% of populations had trends that aligned with the hypothesis that improved DFD treatment in hospital would result in increasing minor amputation rates and decreasing major amputation rates. In contrast, 52% of populations showed decreasing trends for both major and minor rates and the remainder showed a mix of trends. An alternative measure proposed as an indicator of improved hospital DFD treatment and outcomes is a decreasing high to low (hi–low) amputation ratio (i.e. major to minor amputation ratio) [44]. When the hi–low amputation ratios were calculated from the amputation rate findings in this review, nearly all (93%) populations were found to have decreasing hi–low amputation ratios. Thus, it should be noted that improved DFD care may result in decreasing trends in both major and minor amputation rates, in which case the hi–low amputation ratios may not be as sensitive to improved DFD care as previously thought [14, 44]. Regardless, further investigation of standardised hospital admission rates for minor amputations, preferably alongside those for DFD conditions and major amputations, is required to determine the impact of DFD care on these rates and ratios.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, this was a narrative review. Although we performed a systematic search to identify peer-reviewed publications, grey literature was not included and therefore our findings may be subject to selection/publication bias, as grey literature and peer-reviewed publications have reported different hospital admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations in similar national populations [29, 45]. However, a global search of the grey literature was beyond our scope and it is suggested that this is carried out in future research investigating admission rates in smaller regions. Second, although we summarised the overall methodological limitations, we did not perform quality assessments of the included publications, which increases the risk that our findings are subject to bias. While differences in diabetes and DFD care delivered to the populations included are likely to have contributed to some of the trends, potential (rapid) increases in the sizes of populations with diabetes as a result of improved national screening and increases in diabetes prevalence, differences in methods used to identify admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations (including the use of principal vs additional reasons for admission and ICD-9 vs ICD-10 diagnosis codes), differences in the methods used to standardise rates for different population structures over time, and selection bias owing to authors potentially publishing favourable trends may also have contributed to the trends seen [14, 16, 43]. Third, most studies relied on hospital discharge database diagnosis or procedure codes, which have been shown to considerably underestimate admission rates for DFD conditions and to be less accurate for individual DFD conditions than for DFD conditions and amputations combined [10, 41, 46,47,48]. Fourth, we used descriptive statistics to summarise findings from publications that typically used subtly different definitions for admissions, populations and calculating rates and thus we urge caution when comparing rates between publications [16, 43]. Fifth, we reported only descriptive relative trends, regardless of statistical significance and fluctuations in trends over time and the period of time reported for each publication, and thus the magnitudes of trends are not directly comparable between publications and should be interpreted with caution [14, 16, 43]. Indeed, our choice of 5% as a cut-off for increasing or decreasing trends was arbitrary; this cut-off was used only to facilitate a summary of trends across populations with many different definitions. Finally, we did not find any peer-reviewed publications from low-income countries and found only a few from middle-income countries. Our findings are thus unlikely to be representative of these countries.

Implications

First, the hospital admission rates summarised in this review may be useful for forecasting the resources needed to cater for hospital admissions for DFD conditions and amputations. For example, extrapolating the median principal admission rates of 16.3 and 3.1 per 1000 person-years with diabetes for total DFD conditions and total amputations, respectively, to the approximately 536 million adults with diabetes worldwide [2] suggests that there are an estimated 8.7 million hospital admissions for DFD conditions and 1.6 million for amputations annually worldwide, similar to previous estimates [3,4,5, 9]. However, as our findings are based on publications from predominantly high-income countries, and as higher rates were found in the few publications identified from middle-income countries [49,50,51,52,53], these rates are likely to be underestimates.

Second, while the summarised trends in hospital admissions for DFD conditions and amputations should be interpreted with caution, they do provide useful insights [14, 39, 43]. For example, overall trends in admission rates for major amputation seem to be largely decreasing in high-income countries, yet trends in admission rates for minor amputations and DFD conditions are largely inconsistent. However, as mentioned previously, the reasons for these differences in trends are likely to be multiple and include differences in methods used to identify admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations and to identify diabetes and resident populations, differences in the sociodemographic structures of the populations studied, differences in diabetes and DFD care delivered to those populations and selection bias as a result of authors potentially publishing favourable trends [14, 39, 43]. Because of methodological limitations across publications, we were unable to determine the exact impact that these differences had on summarised trends. However, the trends are based on the best evidence available and we provide recommendations in the following section on standardising methodology to enable the reasons for DFD admission trends to be better understood in the future.

Third, this review identified important risk factors for hospital admission for DFD conditions and amputations. Male populations had higher hospital admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations than female populations across all studies in which sex was stratified [23, 37, 54,55,56,57,58,59]. This has also been found for other DFD outcomes, such as neuropathy and ulceration incidence [3, 5, 41]. Further, publications stratifying for age reported that DFD burdens are increasing most rapidly among younger age groups (<40 years) [10, 24, 32, 60]. Additionally, the few publications that stratified for diabetes type found that those with type 1 diabetes generally had slightly higher rates for both DFD conditions and amputations than those with type 2 diabetes [60, 61]. These outcomes support other recent findings showing that age at diabetes onset and diabetes duration may impact DFD outcomes more than other major diabetes complications [62]. As people with diabetes are being diagnosed younger and surviving longer, this suggests that increasing trends in hospital admissions for DFD are likely without intervention [10, 62, 63].

Recommendations

First, like others [14, 39, 42, 43], we recommend the development of global reporting standards for identifying hospital admissions for DFD conditions and amputations and for standardised calculation of incidence rates. We are aware that several countries have proposed using standard ICD coding sets for identifying admissions caused by DFD conditions [12, 48, 64]. Thus, global DFD groups that have developed other reporting standards and definitions [6, 7] should consider developing a consensus on reporting standards for principal admission rates for DFD conditions. In doing so, we recommend that the IDF guide on diabetes epidemiology studies [43], similar work on OECD amputation rate definitions [42], the proposals from countries for standard or modified ICD coding sets to better identify DFD conditions [12, 48, 64] and the common methodologies identified in this review be considered.

Second, we recommend that any global reporting standards developed are tested for validity and reliability in identifying admissions for DFD conditions against gold standard measures, such as prospective clinical bedside audits. Similar studies have been performed previously and have shown that admission rates identified using ICD diagnosis codes considerably underestimate the numbers of people admitted for DFD conditions [10, 41, 46,47,48]. Thus, such studies are important to ensure that hospital discharge dataset coding is as accurate and efficient as possible to be able to monitor the hospital admission burden caused by DFD.

Third, the impact of different factors that may influence or confound admission rates for DFD conditions, such as age, sex, diabetes duration, age at onset, social deprivation, geographic location, and diabetes and DFD care structures, needs further investigation [12,13,14]. Further, investigating risk factors for admission-related outcomes, such as any DFD admission event and length of stay, compared with risk factors for person-related outcomes, such as first DFD admission event per person and in-hospital mortality, should also be considered in future investigations [14, 32, 43]. We are aware of groups that are currently investigating the influence of such risk factors for both admission-related and person-related outcomes for DFD conditions and amputations in various countries and their impending findings should shed new light on issues to consider adjusting for in future global reporting standards [10, 12, 60, 63].

Finally, we recommend that future studies prospectively investigate large population-based cohorts that are representative of national populations with confirmed diabetes or DFD for risk factors for hospital admission for DFD [43]. One such study has found novel risk factors for admission for DFD in large diabetes cohorts, such as younger age [10]. Further, we are aware of studies being conducted that are investigating the risk factors for principal admissions for DFD in large DFD cohorts, as well as the costs of the hospital burden of DFD [18, 63, 65, 66]. Thus, we suggest that these and other hospital admission outcomes, such as length of stay, admission with and without amputation procedures, and mortality, should continue to be investigated to better understand the DFD hospital burden in the future.

Conclusions

This review provides the largest and most comprehensive global picture of trends in hospital admission rates for DFD and amputations. The findings highlight that DFD is a leading cause of hospital admission. The evidence included in this review suggests that the incidence of hospital admissions for DFD conditions is comparable to that for other major diabetes-related complications and is much higher than the incidence of admissions for amputations alone. We also found evidence that major amputation rates have decreased over time, while trends in admissions for DFD conditions and minor amputations were inconsistent. The findings on admission rates for DFD conditions and amputations provide useful estimates that will enable clinicians, researchers and policymakers to benchmark contemporary national incidence rates. Finally, we recommend that global reporting standards for identifying and monitoring principal admission rates for DFD and amputations are developed in order to better understand the seemingly large impact that DFD has on the global burden of disease caused by diabetes and for use as a starting point to develop programmes to reduce this burden.

Abbreviations

- DFD:

-

Diabetes-related foot disease

- IWGDF:

-

International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PAD:

-

Peripheral artery disease

References

Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C et al (2020) Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258):1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S et al (2022) IDF Diabetes Atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 183:109119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119

Zhang Y, Lazzarini PA, McPhail SM, van Netten JJ, Armstrong DG, Pacella RE (2020) Global disability burdens of diabetes-related lower-extremity complications in 1990 and 2016. Diabetes Care 43(5):964–974. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-1614

Lazzarini PA, Pacella RE, Armstrong DG, Van Netten JJ (2018) Diabetes-related lower-extremity complications are a leading cause of the global burden of disability. Diabet Med 35:1297–1299. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13680

Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA (2017) Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med 376(24):2367–2375. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1615439

van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J et al (2020) Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 36(S1):e3268

Jeffcoate WJ, Bus SA, Game FL, Hinchliffe RJ, Price PE, Schaper NC (2016) Reporting standards of studies and papers on the prevention and management of foot ulcers in diabetes: required details and markers of good quality. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 4(9):781–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30012-2

Skrepnek GH, Mills JL, Lavery LA, Armstrong DG (2017) Health care service and outcomes among an estimated 6.7 million ambulatory care diabetic foot cases in the U.S. Diabetes Care 40(7):936–942. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-2189

Lazzarini PA, Hurn SE, Kuys SS et al (2017) The silent overall burden of foot disease in a representative hospitalised population. Int Wound J 14(4):716–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12683

Hamilton EJ, Davis WA, Siru R, Baba M, Norman PE, Davis TME (2021) Temporal trends in incident hospitalization for diabetes-related foot ulcer in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 44(3):722–730. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1743

Zhang Y, Cramb S, McPhail SM et al (2021) Factors associated with healing of diabetes-related foot ulcers: observations from a large prospective real-world cohort. Diabetes Care 44(7):e143–e145. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-3120

Jeffcoate W, Barron E, Lomas J, Valabhji J, Young B (2017) Using data to tackle the burden of amputation in diabetes. Lancet 390(10105):e29–e30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32401-7

Lazzarini PA, Fitridge R (2019) Regional variations in amputation rates: are regional diabetic foot services the reason? ANZ J Surg 89(7-8):796–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.15161

Jeffcoate W, Game F, Morbach S, Narres M, Van Acker K, Icks A (2021) Assessing data on the incidence of lower limb amputation in diabetes. Diabetologia 64(6):1442–1446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05440-4

Narres M, Kvitkina T, Claessen H et al (2017) Incidence of lower extremity amputations in the diabetic compared with the non-diabetic population: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 12(8):e0182081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182081

Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ, Shaw JE, Gregg EW (2019) Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia 62(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4711-2

Moxey PW, Gogalniceanu P, Hinchliffe RJ et al (2011) Lower extremity amputations—a review of global variability in incidence. Diabet Med 28(10):1144–1153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03279.x

Kerr M, Barron E, Chadwick P et al (2019) The cost of diabetic foot ulcers and amputations to the National Health Service in England. Diabet Med 36(8):995–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13973

Schaper NC, Van Netten JJ, Apelqvist J et al (2020) Practical guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 36(S1):e3266. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3266

Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J et al (2014) Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990-2010. N Engl J Med 370(16):1514–1523. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1310799

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2021) Diabetes care. In: Health at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. OECD, Paris, pp 162–163

Shrestha SS, Zhang P, Hora I, Geiss LS, Luman ET, Gregg EW (2019) Factors contributing to increases in diabetes-related preventable hospitalization costs among U.S. adults during 2001-2014. Diabetes Care 42(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-1078

Pearson-Stuttard J, Cheng YJ, Bennett J et al (2022) Trends in leading causes of hospitalisation of adults with diabetes in England from 2003 to 2018: an epidemiological analysis of linked primary care records. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 10(1):46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00288-6

Geiss LS, Li Y, Hora I, Albright A, Rolka D, Gregg EW (2019) Resurgence of diabetes-related nontraumatic lower-extremity amputation in the young and middle-aged adult U.S. population. Diabetes Care 42(1):50–54. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-1380

Hallström S, Svensson AM, Pivodic A et al (2021) Risk factors and incidence over time for lower extremity amputations in people with type 1 diabetes: an observational cohort study of 46,088 patients from the Swedish National Diabetes Registry. Diabetologia 64(12):2751–2761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05550-z

Li Y, Burrows NR, Gregg EW, Albright A, Geiss LS (2012) Declining rates of hospitalization for nontraumatic lower-extremity amputation in the diabetic population aged 40 years or older: U.S., 1988-2008. Diabetes Care 35(2):273–277. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1360

Canavan RJ, Unwin NC, Kelly WF, Connolly VM (2008) Diabetes- and nondiabetes-related lower extremity amputation incidence before and after the introduction of better organized diabetes foot care: continuous longitudinal monitoring using a standard method. Diabetes Care 31(3):459–463. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1159

Carinci F, Massi Benedetti M, Klazinga NS, Uccioli L (2016) Lower extremity amputation rates in people with diabetes as an indicator of health systems performance. A critical appraisal of the data collection 2000-2011 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Acta Diabetol 53(5):825–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-016-0879-4

Kennon B, Leese GP, Cochrane L et al (2012) Reduced incidence of lower-extremity amputations in people with diabetes in Scotland: a nationwide study. Diabetes Care 35(12):2588–2590. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0511

Lombardo FL, Maggini M, De Bellis A, Seghieri G, Anichini R (2014) Lower extremity amputations in persons with and without diabetes in Italy: 2001-2010. PLoS One 9(1):e86405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086405

Vamos EP, Bottle A, Edmonds ME, Valabhji J, Majeed A, Millett C (2010) Changes in the incidence of lower extremity amputations in individuals with and without diabetes in England between 2004 and 2008. Diabetes Care 33(12):2592–2597. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-0989

Lazzarini PA, O’Rourke SR, Russell AW, Derhy PH, Kamp MC (2015) Reduced incidence of foot-related hospitalisation and amputation amongst persons with diabetes in Queensland, Australia. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0130609. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130609

Zhang Y, van Netten JJ, Baba M et al (2021) Diabetes-related foot disease in Australia: a systematic review of the prevalence and incidence of risk factors, disease and amputation in Australian populations. J Foot Ankle Res 14(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-021-00447-x

World Bank (2021) World Bank country and lending groups. World Bank, Washington, DC. Available from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 1 November 2022

Harding JL, Benoit SR, Gregg EW, Pavkov ME, Perreault L (2020) Trends in rates of infections requiring hospitalization among adults with versus without diabetes in the U.S., 2000-2015. Diabetes Care 43(1):106–116. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-0653

Lin CW, Armstrong DG, Lin CH et al (2019) Nationwide trends in the epidemiology of diabetic foot complications and lower-extremity amputation over an 8-year period. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 7(1):e000795. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000795

Wu H, Yang A, Lau ESH et al (2020) Secular trends in rates of hospitalisation for lower extremity amputation and 1 year mortality in people with diabetes in Hong Kong, 2001–2016: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetologia 63(12):2689–2698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05278-2

Benjamin SM, Wang J, Geiss LS, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW (2015) The impact of repeat hospitalizations on hospitalization rates for selected conditions among adults with and without diabetes, 12 US states, 2011. Prevent Chron Dis 12:E200. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150274

Ali MK, Pearson-Stuttard J, Selvin E, Gregg EW (2022) Interpreting global trends in type 2 diabetes complications and mortality. Diabetologia 65(1):3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05585-2

Wu H, Lau ESH, Yang A et al (2020) Trends in diabetes-related complications in Hong Kong, 2001-2016: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 19(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-020-01039-y

Lazzarini PA, Hurn SE, Kuys SS et al (2016) Direct inpatient burden caused by foot-related conditions: a multisite point-prevalence study. BMJ Open 6:e010811. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010811

Carinci F, Uccioli L, Massi Benedetti M, Klazinga NS (2020) An in-depth assessment of diabetes-related lower extremity amputation rates 2000-2013 delivered by twenty-one countries for the data collection 2015 of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Acta Diabetol 57(3):347–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-019-01423-5

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (2021) IDF guide for diabetes epidemiology studies. IDF, Brussels

Wrobel JS, Robbins J, Armstrong DG (2006) The high-low amputation ratio: a deeper insight into diabetic foot care? J Foot Ankle Surg 45(6):375–379. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2006.09.015

Scottish Diabetes Data Group (2017) Scottish Diabetes Survey 2017. Diabetes in Scotland, NHS Scotland; 2017. Available from www.diabetesinscotland.org.uk/publications/. Accessed 11 November 2022

Wraight PR, Lawrence SM, Campbell DA, Colman PG (2006) Retrospective data for diabetic foot complications: only the tip of the iceberg? Intern Med J 36(3):197–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01039.x

Sohn M-W, Budiman-Mak E, Stuck RM, Siddiqui F, Lee TA (2010) Diagnostic accuracy of existing methods for identifying diabetic foot ulcers from inpatient and outpatient datasets. J Foot Ankle Res 3(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1146-3-27

Lukin P, Kuchumov AG, Zarivchatskiy MF, Kravtsova T (2021) Clinical classification of the diabetic foot syndrome adapted to ICD-10 as a solution to the problem of diagnostics, statistics and standardisation. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 57(8):817. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080817

Harding K (2005) Major lower limb amputations in the Marshall Islands: incidence, prosthetic prescription, and prosthetic use after 6-18 months. Pac Health Dialog 12(1):59–66

Kool B, Ipil M, McCool J (2019) Diabetes mellitus-related foot surgeries in the Republic of the Marshall Islands in Micronesia. Hawaii J Med Public Health 78(1):13–18

Laowahutanon T, Nakamura H, Tachimori H et al (2021) Hospital admission for type 2 diabetes mellitus under the Universal Coverage Scheme in Thailand: a time- and geographical-trend analysis, 2009-2016. PLoS ONE 16(7):e0253434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253434

Veresiu IA, Iancu SS, Bondor C (2015) Trends in diabetes-related lower extremities amputations in Romania—a five year nationwide evaluation. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 109(2):293–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2015.05.020

Cisneros-González N, Ascencio-Montiel IJ, Libreros-Bango VN et al (2016) Lower extremity amputation rates in diabetic patients. Revista Medica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social 54(4):472–479

Calderon-Margalit R, Cohen-Dadi M, Opas D et al (2018) Trends in the performance of quality indicators for diabetes care in the community and in diabetes-related health status: an Israeli ecological study. Isr J Health Policy Res 7(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-018-0206-3

Chen HF, Ho CA, Li CY (2006) Age and sex may significantly interact with diabetes on the risks of lower-extremity amputation and peripheral revascularization procedures: evidence from a cohort of a half-million diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 29(11):2409–2414. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-1343

Lopez-de-Andres A, Jimenez-Garcia R, Hernandez-Barrera V et al (2022) Trends of non-traumatic lower-extremity amputation and type 2 diabetes: Spain, 2001-2019. J Clin Med 11(5):1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051246

Manderbacka K, Arffman M, Lumme S, Lehikoinen M, Winell K, Keskimäki I (2016) Regional trends in avoidable hospitalisations due to complications among population with diabetes in Finland in 1996-2011: a register-based cohort study. BMJ Open 6(8):e011620. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011620

Wang J, Imai K, Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Wen C, Zhang P (2009) Secular trends in diabetes-related preventable hospitalizations in the United States, 1998-2006. Diabetes Care 32(7):1213–1217. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-2211

Luk AOY, Wu H, Lau ESH et al (2021) Temporal trends in rates of infection-related hospitalisations in Hong Kong people with and without diabetes, 2001–2016: a retrospective study. Diabetologia 64(1):109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05286-2

Morton JI, Lazzarini PA, Shaw JE, Magliano DJ (2022) Trends in the incidence of hospitalization for major diabetes-related complications in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Australia, 2010-2019. Diabetes Care 45(4):789–797. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-2268

Røikjer J, Jensen MH, Vestergaard P, Sørensen AM, Laursen HVB, Ejskjær N (2020) Twenty years with diabetes and amputations: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Diabet Med 37(12):2098–2108. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14251

Morton JI, Lazzarini PA, Polkinghorne KR, Carstensen B, Magliano DJ, Shaw JE (2022) The association of attained age, age at diagnosis, and duration of type 2 diabetes with the long-term risk for major diabetes-related complications. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 190:110022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110022

Zhang Y, Cramb S, McPhail SM et al (2022) Multiple factors predict longer and shorter time-to-ulcer-free in people with diabetes-related foot ulcers: survival analyses of a large prospective cohort followed-up for 24-months. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 185:109239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109239

Lazzarini PA, van Netten JJ, Fitridge R et al (2018) Pathway to ending avoidable diabetes-related amputations in Australia. Med J Australia 209(7):288–290. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.01198

Zhang Y, Carter HE, Lazzarini PA et al Cost-effectiveness of guideline-based care provision for patients with diabetes-related foot ulcers: a modelled analysis using discrete event simulation. Diabet Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14961

NHS Digital (2019) National diabetes foot care audit: fourth annual report. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, London. Available from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-diabetes-footcare-audit. Accessed 11 November 2022

Fosse-Edorh S, Mandereau-Bruno L, Hartemann A (2016) Socio-economic and territorial disparities in the management of diabetic foot in France, in 2015. Medecine des Maladies Metaboliques 10(6):501–508

Fosse-Edorh S, Mandereau-Bruno L, Hartmann-Heurtier A (2015) Hospitalization for podiatric complications in people pharmacologically treated for diabetes in France, in 2013. Bull Epidémiol Hebd 34-35:638–644

Amadou C, Denis P, Cosker K, Fagot-Campagna A (2020) Less amputations for diabetic foot ulcer from 2008 to 2014, hospital management improved but substantial progress is still possible: a French nationwide study. PLoS ONE 15(11):e0242524. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242524

Hsieh HM, Lin TH, Lee IC, Huang CJ, Shin SJ, Chiu HC (2016) The association between participation in a pay-for-performance program and macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Prev Med 85:53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.12.013

Park JH, Ha KH, Kim BY, Lee JH, Kim DJ (2021) Trends in cardiovascular complications and mortality among patients with diabetes in South Korea. Diabetes Metab J 45(1):120–124. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0175

Hopkins RB, Burke N, Harlock J, Jegathisawaran J, Goeree R (2015) Economic burden of illness associated with diabetic foot ulcers in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 15:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0687-5

Winell K, Niemi M, Lepantalo M (2006) The national hospital discharge register data on lower limb amputations. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 32(1):66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.12.025

Nijenhuis-Rosien L, Hendriks SH, Kleefstra N, Bilo HJ, Landman GW (2017) Nationwide diabetes-related lower extremity amputation rates in secondary care treated patients with diabetes in the Netherlands (DUDE-7). J Diabetes Complicat 31(4):675–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.01.015

Sheen YJ, Kung PT, Kuo WY, Chiu LT, Tsai WC (2018) Impact of the pay-for-performance program on lower extremity amputations in patients with diabetes in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore) 97(41):e12759. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012759

Lai YJ, Hu HY, Lin CH, Lee ST, Kuo SC, Chou P (2015) Incidence and risk factors of lower extremity amputations in people with type 2 diabetes in Taiwan, 2001-2010. J Diabetes 7(2):260–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12168

Imam B, Miller WC, Finlayson HC, Eng JJ, Jarus T (2017) Incidence of lower limb amputation in Canada. Can J Public Health 108(4):e374–e380. https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.108.6093

Icks A, Haastert B, Trautner C, Giani G, Glaeske G, Hoffmann F (2009) Incidence of lower-limb amputations in the diabetic compared to the non-diabetic population. Findings from nationwide insurance data, Germany, 2005-2007. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 117(9):500–504. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1225333

Walicka M, Raczyńska M, Marcinkowska K et al (2021) Amputations of lower limb in subjects with diabetes mellitus: reasons and 30-day mortality. J Diabetes Res 2021:8866126. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8866126

Claessen H, Narres M, Haastert B et al (2018) Lower-extremity amputations in people with and without diabetes in Germany, 2008-2012—an analysis of more than 30 million inhabitants. Clin Epidemiol 10:475–488. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S146484

Robinson TE, Kenealy T, Garrett M, Bramley D, Drury PL, Elley CR (2016) Ethnicity and risk of lower limb amputation in people with type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabet Med 33(1):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12807

Fosse S, Hartemann-Heurtier A, Jacqueminet S, Ha Van G, Grimaldi A, Fagot-Campagna A (2009) Incidence and characteristics of lower limb amputations in people with diabetes. Diabet Med 26(4):391–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02698.x

Buckley CM, O'Farrell A, Canavan RJ et al (2012) Trends in the incidence of lower extremity amputations in people with and without diabetes over a five-year period in the Republic of Ireland. PLoS ONE 7(7):e41492. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041492

Khavjou OA, Saydah SH, Zhang P et al (2019) Estimating state-level health burden of diabetes: diabetes-attributable fractions for diabetes complications. Am J Prev Med 56(2):232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.09.023

Ólafsdóttir AF, Svensson AM, Pivodic A et al (2019) Excess risk of lower extremity amputations in people with type 1 diabetes compared with the general population: amputations and type 1 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 7(1):e000602. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2018-000602

González-Touya M, Carmona R, Sarría-Santamera A (2021) Evaluating the impact of the diabetes mellitus strategy for the national health system: an interrupted time series analysis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 9(7):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070873

Holman N, Young RJ, Jeffcoate WJ (2012) Variation in the recorded incidence of amputation of the lower limb in England. Diabetologia 55(7):1919–1925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2468-6

Winell K, Venermo M, Ikonen T, Sund R (2013) Indicators for comparing the incidence of diabetic amputations: a nationwide population-based register study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 46(5):569–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.07.010

Dillon MP, Fortington LV, Akram M, Erbas B, Kohler F (2017) Geographic variation of the incidence rate of lower limb amputation in australia from 2007-12. PLoS ONE 12(1):e0170705. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170705

Squires DA (2011) The U.S. health system in perspective: a comparison of twelve industrialized nations. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 16:1–14

Venermo M, Manderbacka K, Ikonen T, Keskimäki I, Winel K, Sund R (2013) Amputations and socioeconomic position among persons with diabetes mellitus, a population-based register study. BMJ Open 3(4):e002395. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002395

Kolossváry E, Ferenci T, Kováts T et al (2015) Trends in major lower limb amputation related to peripheral arterial disease in Hungary: a nationwide study (2004-2012). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 50(1):78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.02.019

Wierzba W, Krasnodębski P, Śliwczyński A, Karnafel W (2020) Geographic variability of major non-traumatic lower limb amputations in diabetic and non-diabetic patients in Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med AAEM 27(1):76–79. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/114725

Gurney JK, Stanley J, York S, Sarfati D (2019) Regional variation in the risk of lower-limb amputation among patients with diabetes in New Zealand. ANZ J Surg 89(7-8):868–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.15079

Ikonen TS, Sund R, Venermo M, Winell K (2010) Fewer major amputations among individuals with diabetes in Finland in 1997-2007: a population-based study. Diabetes Care 33(12):2598–2603. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-0462

Claessen H, Avalosse H, Guillaume J et al (2018) Decreasing rates of major lower-extremity amputation in people with diabetes but not in those without: a nationwide study in Belgium. Diabetologia 61(9):1966–1977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4655-6

Kamitani F, Nishioka Y, Noda T et al (2021) Incidence of lower limb amputation in people with and without diabetes: a nationwide 5-year cohort study in Japan. BMJ Open 11(8):e048436. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048436

Lopez-de-Andres A, Jimenez-Garcia R, Hernández-Barrera V et al (2022) Time trends (2001-2019) and sex differences in incidence and in-hospital mortality after lower extremity amputations among patients with type 1 diabetes in Spain. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1):65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01502-y

Riandini T, Pang D, Toh M et al (2022) National rates of lower extremity amputation in people with and without diabetes in a multi-ethnic Asian population: a ten year study in Singapore. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 63(1):147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.09.041

Lopez-de-Andres A, Jiménez-García R, Aragón-Sánchez J et al (2015) National trends in incidence and outcomes in lower extremity amputations in people with and without diabetes in Spain, 2001-2012. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 108(3):499–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.010

Aziz F, Reichardt B, Sourij C et al (2020) Epidemiology of major lower extremity amputations in individuals with diabetes in Austria, 2014–2017: a retrospective analysis of health insurance database. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 170:108477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108477

Akinlotan MA, Primm K, Bolin JN et al (2021) Racial, rural, and regional disparities in diabetes-related lower-extremity amputation rates, 2009-2017. Diabetes Care 44(9):2053–2060. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-3135

Rodríguez Pérez MDC, Chines C, Pedrero García AJ et al (2020) Major amputations in type 2 diabetes between 2001 and 2015 in Spain: regional differences. BMC Public Health 20(1):54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8137-7

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Authors’ relationships and activities

PAL and JJvN declare that they are members of the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) working groups and editorial board, respectively, which are responsible for authoring international evidence-based guidelines on DFD management. The authors declare that there are no other relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Contribution statement

PAL contributed to the conception and design of the study, literature search, data extraction, analyses and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. SMC contributed to the study design, data extraction, analyses and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JG, JIM and DJM contributed to the study design, analyses and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JJvN contributed to the conception and design of the study, analyses and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. PAL is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole and is also the guarantor of this work.

Funding

Work in the authors’ groups is supported by various funding sources, including an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship Grant (#1143435) to PAL; an NHMRC Investigator Grant (#2008313) to SMC; NHMRC, Australian Heart Foundation, Medical Research Futures Fund and Queensland Government grants to JG; an Australian Government Research Training Program grant and a Monash Graduate Excellence Scholarship to JIM; an Alice Baker and Eleanor Shaw Gender Equity Fellowship to DJM; and grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) to JJvN. However, the authors declare that these funding sources had no role in the development of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM

(PDF 896 kb)

Slideset of figures

(PPTX 477 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lazzarini, P.A., Cramb, S.M., Golledge, J. et al. Global trends in the incidence of hospital admissions for diabetes-related foot disease and amputations: a review of national rates in the 21st century. Diabetologia 66, 267–287 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05845-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05845-9