Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The aim of this work was to investigate clinical outcomes following severe hypoglycaemia requiring prehospital emergency medical services (EMS) management.

Methods

We carried out a prospective, observational study of adults with diabetes attended by prehospital EMS for management of severe hypoglycaemia between April 2016 and July 2017. Information on precipitants, hospitalisation, length of hospital stay and recurrence was collected at 1 and 3 months following the episode of severe hypoglycaemia. Median and logistic regression models examined predictive factors.

Results

Five hundred and five adults (61% male, median age 67 years) participated in the study. Fifty-two per cent had type 1 diabetes, 43% type 2 diabetes and 5% were unsure of their diabetes type. Following EMS management of the index episode of severe hypoglycaemia, 50.3% were transported to hospital. Of those transported, 41.3% were admitted to hospital for ongoing management (20.8% of all participants). The following factors predicted hospital admission: older age (OR 1.28 [95% CI 1.02, 1.60] per 10 years), greater number of comorbidities (OR 1.27 [95% CI 1.08, 1.48] per morbidity), moderate–severe injury accompanying the hypoglycaemia (OR 5.24 [95% CI 1.07, 25.8] compared with nil–mild injury) and unknown cause of hypoglycaemia (OR 2.21 [95% CI 1.24, 3.94] compared with known cause). The median (interquartile range) length of hospital stay was 4 (2–7) days. During follow-up, recurrent severe hypoglycaemia attended by prehospital EMS was experienced by 10.7% of participants. Predictive factors of recurrent severe hypoglycaemia in 3 months were decreased HbA1c (OR 1.97 [95% CI 1.27, 3.06] per 10 mmol/mol decrease) and a greater number of antecedent severe hypoglycaemia episodes (OR 1.12 [95% CI 1.03, 1.23] per episode).

Conclusions/interpretation

Following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia managed by EMS, one-fifth of participants required hospital admission, more likely in those with advancing age, increasing comorbidities and injury and one-tenth required EMS again for severe hypoglycaemia in a 3 month period, more likely in those with a greater number of antecedent episodes and lower HbA1c. Knowledge of these factors associated with admission and recurrence provides an opportunity for development of targeted strategies aimed at prevention of severe hypoglycaemia in those most vulnerable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hypoglycaemia among those with diabetes is a common and potentially avoidable complication of therapy [1]. When cognitive impairment necessitates external assistance for treatment, the hypoglycaemia is classified as severe [2] and may require the assistance of prehospital emergency medical services (EMS). Following immediate treatment by EMS in the community, individuals may be transported to a hospital for further care, from where they may be discharged or admitted to a ward. While immediate attendance to a hospital emergency department may not be necessary, medical review of the treatment regimen is advised for all patients [3]. In the weeks following occurrence of the severe hypoglycaemia, a period of relaxed glucose targets may be recommended, in order to reduce risk of recurrence and to restore symptoms and hypoglycaemia awareness [2].

Studies following individuals for up to 3 days after an episode of severe hypoglycaemia have suggested that many of them may remain safely at home after acute treatment [4,5,6,7,8,9], with minimal difference in symptom recurrence between those who are and are not transported to hospital. However, the detailed patient trajectory following the transport decision, including length of hospital stay and recurrence in the months following, when the individual may be particularly vulnerable to adverse clinical outcomes, has not been well studied.

The primary aims of this study were to investigate factors associated with hospitalisation, length of hospital stay and recurrence in the 3 months following the index episode of severe hypoglycaemia managed by prehospital EMS. Secondary aims were to describe precipitants and prior care management of severe hypoglycaemia managed by prehospital EMS as well as behaviours of follow-up medical review. By understanding the common precipitants and the clinical outcomes following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia, as they relate to predisposing factors, high-risk populations can be identified and strategies to reduce and/or improve use of EMS for management of severe hypoglycaemia can be developed.

Methods

Study design

We carried out a prospective, observational study of adults (aged >17 years) with diabetes mellitus (type 1 or type 2) experiencing an episode of severe hypoglycaemia managed by Ambulance Victoria between April 2016 and July 2017 (approximately 15 months). Following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia, potential participants were identified through Ambulance Victoria’s electronic data warehouse. Exclusion criteria were age ≤17 years, nil diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes and living in a residential care facility. Ambulance Victoria’s Clinical Practice Guidelines specify a blood glucose level of <4 mmol/l, with associated symptoms, as the treatment threshold for hypoglycaemia [10]. This study was approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (project no. CF15/3091 – 2015001303) prior to data collection.

Setting

This study was conducted in the state of Victoria, Australia, which had a population of 6.29 million at March 2017 [11]. Victoria is serviced by Ambulance Victoria, a two-tiered prehospital EMS system, which deploys Advanced Life Support and Intensive Care paramedics and deals with over 500,000 emergency cases annually [12]. Approximately 1% of cases attended by Ambulance Victoria are classified as hypoglycaemia [13].

Data sources and recruitment

An electronic patient care record is completed for every individual attended by Ambulance Victoria, by the paramedic, during the episode of care. Clinical data from the electronic patient care record and operational data from the computer-aided dispatch system are uploaded to the Ambulance Victoria electronic data warehouse. Potential participants were identified weekly through the Ambulance Victoria electronic database and were sent a letter of invitation. Telephone contact was initiated approximately 4 weeks following the index episode and consenting participants were surveyed over the phone with regards to general and diabetes-related health and management practices. Prior to participation in this study, participants gave informed consent. Participants were surveyed again at 3 months after the index episode in order to collect information regarding health and clinical outcomes. A pre-calculated sample size was chosen to capture the experiences of individuals with diabetes from a range of demographic situations, ages and locations. Recruitment commenced on 24 April 2016 and continued for 15 months until the desired sample size was reached on 25 July 2017.

Outcome variables

The main outcome variables were as follows: (1) hospital admission (yes, if participant attended hospital within 24 h following the episode and was admitted); (2) length of stay (days, if admitted) and (3) recurrence (yes, if participant experienced at least one episode of severe hypoglycaemic managed by EMS within the 3 months of index episode). Hospital admission and length of stay were self-reported and data on recurrence were obtained from the Ambulance Victoria data warehouse. Other outcome variables were as follows: (1) the main precipitant of hypoglycaemia, classified as related to food, exercise or activity, insulin, other medication, intercurrent illness or other or unknown; (2) prior treatment attempted (either by the participant or others at scene), classified as oral carbohydrate, glucagon or neither oral carbohydrate or glucagon and (3) attendance to medical review (general practitioner, endocrinologist or diabetes educator) within 7 days of episode or within 7 days of hospital discharge in those who attended hospital.

Predictor variables

The predictor variables were pre-specified and were self-reported, except where extracted from the electronic patient care record, as stated. Basic demographic variables were sex, age in years, location of residence (classified as metropolitan or regional as per the Regional Development Victoria Geography Structure [14]) and living situation (alone or with others). The country of birth was classified as Australia or overseas. Employment status, classified as employed, unemployed or retired and recipient of government benefit status, was ascertained. Prehospital EMS care in the state of Victoria is provided free of charge for government benefit recipients.

Diabetes-related variables were diabetes type (type 1, type 2 or unknown), diabetes duration (years), treatment with insulin, sulfonylurea use, the estimated number of severe hypoglycaemia episodes in the 12 months prior to index episode (any episode requiring assistance of others) and HbA1c result if known by participants and measured within the last 3 months. HbA1c was self-reported and collected in percentage units, as this was the measurement most participants were familiar with, and was converted to mmol/mol for analysis. Diabetes medical care provider was classified as general practitioner only, specialist practitioner (endocrinologist) only, both general practitioner and specialist care or neither. The self-reported frequency of attendance to a physician for diabetes (either general practitioner or endocrinologist) was classified as follows: monthly or more frequently; less than monthly to 3 monthly; less than 3 monthly to 6 monthly and less frequent than 6 monthly. The number of comorbidities (additional to diabetes) was recorded from the electronic patient care record. Diagnosis of specific medical conditions, including heart disease, renal disease, cerebrovascular disease (including stroke and transient ischaemic attack), depression and anxiety, was ascertained. In addition, the specific medical diagnoses to allow the calculation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, a measure of prognostic comorbidity that assigns weighted scores from 22 comorbid conditions and predicts 1 year mortality risk [15], were collected. Interpretation of these scores is described in detail elsewhere [15].

The following variables related to the index episode of hypoglycaemia were extracted from the paramedic electronic patient care record: time of day of index episode (00:00 hours to before 08:00 hours, 08:00 hours to before 16:00 hours, 16:00 hours to before 00:00 hours); the Glasgow Coma Score and blood glucose level (mmol/l) on presentation (initial) and following hypoglycaemia treatment (final); the prehospital EMS treatment provided (oral treatment only [glucose paste or complex carbohydrate] or parenteral treatment [intramuscular glucagon or intravenous glucose]) and whether hospital transport was provided by EMS. Self-reported, episode-related variables were the presence of intercurrent illness and self-rated injury (classified as none–mild or moderate–severe).

Statistical methods

Summary results were presented as percentage for categorical variables and as median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables; Spearman ρ was reported where both the predictor and outcome variables were continuous (such as in length of stay). To assess representation of the sample against eligible non-participants, differences in sex, age, location of residence, diabetes type and treatment with insulin were compared, using χ2 test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate.

Precipitants of hypoglycaemia, prior treatment attempted and follow-up medical review were presented descriptively. Multivariable analysis was performed with the main outcome variables hospital admission, length of stay and 3 month recurrent episode. Factors associated with hospital admission (yes/no) and 3 month recurrent episode (yes/no) were analysed using mixed effects logistic regression. The mixed models were chosen to account for clustering of participants within the same postcode. The hospital length of stay was noted to have a positively skewed distribution, so regression of the median with robust standard error was used to analyse factors associated with admission length of stay. Univariable analysis was initially performed. Multivariable models were constructed in a stepwise manner. Starting from the most significant variables, variables identified to yield a p value <0.05 in the univariable analysis were consecutively added to the model. Following the addition of each variable, a likelihood ratio test was performed and the variable was retained in the model where the likelihood ratio yielded a p value <0.05 and was thus deemed to improve the model. Given the importance of age and diabetes type, these variables were forced into the models in the initial stages of the multivariable modelling process. Where data were missing, every effort was made to contact participants for rectification. Missing data were minimal and no imputation of missing data was performed. Participants with missing data for a particular variable were not included in the analysis pertaining to that particular variable but were not excluded from other analyses where relevant data were available. All analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) version 14.0.

Results

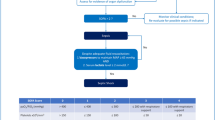

Ambulance Victoria managed 4510 episodes of severe hypoglycaemia among 3479 adults, of which a sample of 505 were prospectively studied during the 15 month study period (see electronic supplementary material [ESM] Fig. 1). Initial surveys were completed at a median (IQR) of 28 (24, 33) days following the index severe hypoglycaemia event. Most of the cohort (88.3%, n = 446) were contactable at 3 months (final survey), with a median (IQR) follow-up of 99 (93–109) days after the index severe hypoglycaemia event. The following reasons for incomplete follow-up were reported: decline (2.2%, n = 11); moved to residential care facility (0.6%, n = 3); deceased (1.2%, n = 6) and unable to contact (7.7%, n = 39).

Study population characteristics

Participant characteristics, overall and by diabetes type, are presented in Table 1. Over half (51.9%) the participants had type 1 diabetes, 42.8% had type 2 diabetes and 5.3% were unsure of their diabetes type. The median (IQR) age of participants was 67 (56–77) years, 60.6% were men and 68.7% resided in a metropolitan location. Over 80% of participants had at least one comorbidity in addition to diabetes, with a median (IQR) of 2 (1–3) comorbidities and a median (IQR) Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 4 (2–6). Most (65.3%) of participants were retired, 24.6% were employed and 10.1% were unemployed. Overall, 70.9% were recipients of a government benefit. Participants born in a country outside Australia made up 28.1%. Compared with eligible non-participants, the sample was of similar sex (p = 0.496), diabetes type (p = 0.361) and location of residence (metropolitan/regional, p = 0.109). However, participants were older, by a median of 6 years (p < 0.001), and a greater proportion were treated with insulin compared with non-participants (91% vs 54%, p < 0.001) (ESM Table 1).

Precipitants of severe hypoglycaemia and prior management

The self-reported primary precipitant of severe hypoglycaemia included food (28.9%), insulin (17.3%), exercise/activity (8.3%), intercurrent illness (5.5%), other medications (4.5%) and other cause (5.4%). Almost one-third of participants (30.1%) were unsure of the reason for development of hypoglycaemia. In 60.8% of the episodes, hypoglycaemia treatment was attempted prior to prehospital EMS arrival; 55.1% were given oral carbohydrate and 5.7% were given intramuscular glucagon (with or without oral carbohydrate). Where prior treatment was not attempted, the following reasons were given: participant was unconscious (including seizure) (64.1%); hypoglycaemia was not recognised as such (including suspected stroke/cardiac problems) (21.7%); uncertainty of what to do (6.1%); no treatment was available (1.5%) and other reasons (6.6%).

Predictors of hospital admission

Of the 505 participants, 50.3% (n = 254) were transported to the emergency department within 24 h (249 immediately by paramedics or private car and 5 later by private car). Of these, 58.7% (n = 149) were discharged from the emergency department and 41.3% (n = 105) were admitted to a hospital ward, representing 20.8% of the whole cohort. Factors associated with hospital admission are presented in Table 2. Hospital admission was predicted by increased age (OR 1.28 [95% CI 1.02, 1.60]), increasing number of comorbidities (OR 1.27 [95% CI 1.08, 1.48]), moderate–severe injury sustained with severe hypoglycaemia (OR 5.24 [95% CI 1.07, 25.8]) and unknown cause of hypoglycaemia (OR 2.21 [95% CI 1.24, 3.94]).

Length of hospital stay

For the 105 participants admitted to a hospital ward following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia, the median (IQR) length of stay was 4 (2–7) days (ESM Fig. 2). Independent predictors of length of hospital stay (Table 3) were type 2 diabetes and heart disease. Type 2 diabetes was associated with an increase in the median length of stay of 2 (95% CI 0.11, 3.89) days, compared with type 1 diabetes, and a history of heart disease was associated with an increase in the median length of stay of 2 (95% CI 0.36, 3.64) days compared with no history of heart disease. There was a suggestion of an increasing length of stay among those treated with sulfonylureas (7 days vs 4 days, p = 0.083) compared with those not treated with this medication.

Predictors of recurrent severe hypoglycaemia requiring prehospital EMS

Of the 505 participants, 10.7% (n = 54) had one or more recurrent episodes of severe hypoglycaemia requiring EMS in the 3 months following the index episode, generating a total of 602 occurrences during follow-up. The median (IQR) number of recurrent episodes was 2 (2–3) and the median (IQR) time between episodes was 28 (8–50) days. Predictors of recurrent severe hypoglycaemia are presented in Table 4. Recurrent severe hypoglycaemia was independently associated with lower HbA1c (OR 1.97 [95% CI 1.27, 3.06] for every 10 mmol/mol decrease) and a greater number of antecedent severe hypoglycaemia episodes (OR 1.12 [95% CI 1.03, 1.23] per increase by one episode).

Follow-up review with primary diabetes care provider

Overall, 56.2% (n = 284) of participants attended a diabetes review appointment (involving a general practitioner, endocrinologist or diabetes educator) within 7 days of the episode or hospital discharge (where admission had occurred). Of those who attended a review, over half (52.1% [n = 148]) reported a change to their diabetes medication or management. Of those who did not attend an emergency department following EMS management of severe hypoglycaemia, approximately half (52.2% [n = 131]) attended a diabetes review appointment within 7 days. Overall, 23.8% (n = 120) did not attend an emergency department or a diabetes review appointment within 7 days following the episode. Non-attendance at an emergency department or a diabetes medical review within 7 days was not associated with the risk of recurrent severe hypoglycaemia within 3 months of initial episode (OR 1.55 [95% CI 0.84, 2.87], p = 0.161) (Table 4).

Discussion

This is the largest prospective study of short- and medium-term outcomes of people with diabetes following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia managed by prehospital EMS. Following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia, one-fifth of the participants required hospital admission predicted by advancing age, increasing number of comorbidities, injury associated with hypoglycaemia and unknown cause of hypoglycaemia. The median (IQR) length of hospital stay was 4 (2–7) days, increased in those with a history of type 2 diabetes or heart disease. Within 3 months of the index severe hypoglycaemia episode, 10% experienced another episode requiring EMS management, predicted by a lower HbA1c and greater number of antecedent severe hypoglycaemia episodes.

Of note, many participants were able to recognise the major precipitant for their severe hypoglycaemia. The reasons provided were generally consistent with those described by other studies [16,17,18] with most participants reporting reduced food intake or increased insulin administration. However, about 30% were unsure of the cause, suggesting that some participants may have impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia or not have sufficient knowledge of precipitants or risk factors for hypoglycaemia. Accordingly, strategies to educate people on the prevention of hypoglycaemia are required to reduce future burden for EMS care.

Attempts to treat the hypoglycaemia prior to EMS arrival occurred in approximately 60% of the episodes, less than 6% involving use of glucagon. Where no treatment was attempted, a large proportion of participants reported this was due to an altered level of consciousness. In addition, hypoglycaemia was not recognised as such in a substantial proportion of conscious individuals. This suggests that targeted education to assist individuals with diabetes and their family with earlier recognition and treatment of symptoms as soon as they are feeling unwell, prior to loss of consciousness, as well as appropriate use of glucagon, may reduce the need for prehospital EMS care. Indeed, greater prescription and use of glucagon may be of particular benefit to those with impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia.

Following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia, over 40% of participants who attended an emergency department required hospital admission. This is within the wide range of admission rates reported in previous studies [5, 6, 19,20,21]. Predictors of hospital admission were older age, number of comorbidities, injury associated with severe hypoglycaemia and unknown cause of severe hypoglycaemia. Knowledge of these factors may be used by paramedics and emergency clinicians to risk-stratify individuals to identify those requiring hospital transfer and/or those most vulnerable to adverse outcomes.

The median (IQR) length of hospital stay was 4 (2–7) days and a diagnosis of heart disease or type 2 diabetes independently predicted longer length of hospital stay. These results are especially important in light of the increasing prevalence of both diseases in an ageing population. Education regarding hypoglycaemia avoidance especially for people with type 2 diabetes and/or heart disease must clearly be a high priority for health systems and may be of particular interest to those involved in diabetes education. Our analysis pointed to an increased length of hospital stay in those treated with sulfonylureas (7 days vs 4 days, p = 0.083). This is consistent with previous literature reporting that patients with sulfonylurea-related hypoglycaemia require a long hospital stay and are at risk of recurrent in-hospital hypoglycaemia and recurrent hospital admission [22] and supports the recommendations for admission of individuals with hypoglycaemia caused by a sulfonylurea drug [23].

Medical review with a diabetes care professional is recommended following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia, to allow examination of treatment targets, make necessary adjustments and improve understanding of precipitants [24]. Frequency of medical review following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia reported in the literature varies from 34% to 60% [4, 7, 9, 18, 25] and our finding (56.2%) is consistent with this. Of those who did not attend a medical review appointment (43.8% [n = 221]), about half (n = 101) had attended an emergency department and may have considered a separate medical review appointment unnecessary. Nonetheless, the 23.8% who did not attend an emergency department or a diabetes review appointment following the episode may be of concern. Severe hypoglycaemia requiring hospitalisation has previously been shown to be associated with increased mortality rate in older adults [26]. However, the authors of this paper and others [27, 28] point to hypoglycaemia being a marker of vulnerability to adverse events rather than it being a contributing factor. Thus, medical review following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia is paramount and may be as important as preventative strategies. Although medical review following an episode of severe hypoglycaemia was not found to reduce future episodes in this study, it serves as an opportunity for a general health assessment with a focus on frailty, falls risk, polypharmacy and an opportunity to optimise the management of comorbidities and reassess blood glucose targets.

Previous studies [29, 30] have evaluated interventions following the use of EMS for severe hypoglycaemia. Individuals who remained at home following EMS treatment for hypoglycaemia were given an information leaflet [29] or prompt card [30] and were later contacted by phone for a follow-up medical appointment. Both studies reported high levels of patient satisfaction and confidence in the ability to prevent future episodes [29]. Where an appointment was offered, almost 80% of individuals attended the appointment [29]. Given the high proportion of individuals who did not have medical contact following an episode in the current study, future research could examine the feasibility of more proactive paramedic-led interventions in the local setting.

Over a 3 month follow-up, 10% of the participants in our study had at least one recurrent episode of severe hypoglycaemia; recurrence was more likely in those with a lower HbA1c and a greater number of antecedent episodes. Our results are consistent with previous literature showing increased risk of hypoglycaemia in those with tightly controlled type 2 diabetes [31, 32] and those with prior episodes of hypoglycaemia [33, 34]. Our study further adds that these factors extend to the prehospital EMS setting and highlights the need for consideration of relaxed glucose targets and increased preventative measures, such as sensor technology, in those most vulnerable.

Our study is comparable with previous research [21] examining the use of emergency health services for severe hypoglycaemia in Tayside, Scotland. This study found that people who had an episode of severe hypoglycaemia requiring emergency treatment (including from prehospital emergency services, hospital emergency departments and primary care) were older, had a longer duration of diabetes and a higher HbA1c, than those who did not. An association between lower socioeconomic status and increased incidence of emergency treatment for severe hypoglycaemia was also reported in the same study cohort [35]. Our study expands on this by examining factors associated with later hospital admission, length of stay and recurrence outcomes and finds similar themes, where admission is associated with older age and recurrence is associated with HbA1c, but not socioeconomic status.

This is the first study to link prehospital EMS factors with later hospital outcomes and is strengthened by its large sample size and prospective design. Results are generalisable to other developed countries with extensive prehospital EMS systems. This study has some limitations. Our sample was largely a retired cohort, who were older and more likely to be treated with insulin, and this may affect the generalisability of results. Self-reported data are used in this study and may be subject to interpretation and memory. However, with regards to severe hypoglycaemia at least, self-reports are said to be reliable for up to 12 months [36]. Of the 2540 individuals eligible for the study, 20% (n = 505) participated. As this was a phone-based survey, and there were a large number of people for whom a telephone number was not provided on the electronic patient care record, this may have contributed to the resultant response rate.

Furthermore, it should be noted that only individuals who contacted prehospital EMS were examined in this study and those who attended hospital emergency departments directly were not included. Previous research suggests those who attend hospital emergency departments directly form a minority of those who require emergency assistance [21] and may form a distinct subgroup with a different profile.

Conclusion

This large prospective study has identified common precipitants and prior management of severe hypoglycaemia, as well as studied the patient trajectory from transport to an emergency department, hospital admission and recurrent requirement of EMS in the following months. Our findings regarding poor recognition of precipitants and treatment of early warning signs of hypoglycaemia in some, will be of interest to those involved in diabetes education. Following management by EMS, approximately 20% of participants required hospital admission, for a median (IQR) of 4 (2–7) days, predicted by older age, greater number of comorbidities, injury sustained with severe hypoglycaemia and unknown cause of severe hypoglycaemia. These data serve to inform EMS clinicians, attending at the scene, of those most vulnerable and may assist in transport decision. Furthermore, the finding that almost one-quarter of participants did not attend an emergency department or a diabetes review appointment is of concern and investigation of strategies to increase the rate of medical follow-up are warranted. Finally, those with lower HbA1c and increased number of antecedent episodes of severe hypoglycaemia were at greatest risk of a recurrent episode requiring EMS, and this finding supports interventions such as education and use of sensor technology to improve patient safety. The results of this study will assist those caring for people at risk of hypoglycaemia to promote increased vigilance and awareness of strategies aimed at reducing this life-threatening but preventable diabetic complication.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EMS:

-

Emergency medical services

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

References

Morales J, Schneider D (2014) Hypoglycemia. Am J Med 127:17–24

Seaquist E, Anderson J, Childs B et al (2013) Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care 36(5):1384–1395. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-2480

American Diabetes Association (2018) Standards of medical care in diabetes: 14. Diabetes care in the hospital. Diabetes Care 41:144–151

Cain E, Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Alexiadis P, Murray D (2003) Prehospital hypoglycemia: the safety of not transporting treated patients. Prehosp Emerg Care 7(4):458–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/312703002193

Anderson S, Hogskilde P, Wetterslev J et al (2002) Appropriateness of of leaving emergency medical service treated patients at home: a retrospective study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 46(4):464–468. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460424.x

Socransky S, Pirrallo R, Rubin J (1998) Out-of-hospital treatment of hypoglycaemia: refusal of transport and patient outcome. Acad Emerg Med 5(11):1080–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02666.x

Lerner E, Billittier A, Lance D, Janicke D, Teuscher J (2003) Can paramedics safely treat and discharge hypoglycaemic patients in the field? Am J Emerg Med 21(2):115–120. https://doi.org/10.1053/ajem.2003.50014

Carter A, Keane P, Dreyer J (2002) Transport refusal by hypoglycemic patients after on-scene intravenous dextrose. Acad Emerg Med 9(8):855–857. https://doi.org/10.1197/aemj.9.8.855

Strote J, Simons R, Eisenberg M (2008) Emergency medical technician treatment of hypoglycemia without transport. Am J Emerg Med 26(3):291–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.05.030

Ambulance Victoria. Clinical practice guidelines for ambulance and MICA paramedics. 2016 Edition Update. Available from http://www.ambulance.vic.gov.au/Paramedics/Qualified-Paramedic-Training/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines.html. Accessed 15 Jun 2016

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian demographic statistics, Mar 2017. Cat. no. 3101.0 ABS, Canberra, ACT. Available from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/3101.0Media Release1Mar 2017. Accessed 24 Nov 2017

Ambulance Victoria Annual Report 2014–2015. Available from https://www.ambulance.vic.gov.au/about-us/our-performance/. Accessed 15 Jun 2016

Villani M, Nanayakkara N, Ranasinha S et al (2016) Utilisation of emergency medical services for severe hypoglycaemia: an unrecognised health care burden. J Diabetes Complicat 30(6):1081–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.04.015

Regional Development Victoria Geography Structure. Victorian State Goverment. 2018. Available from http://www.rdv.vic.gov.au/information-portal/more-information/geography-structure. Accessed 19 Mar 2018

Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, MacKenzie C (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Amiel S, Dixon T, Mann R, Jameson K (2008) Hypoglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 25(3):245–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02341.x

International Hypoglycaemia Study Group (2015) Minimizing hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care 38(8):1583–1591. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-0279

Lammert M, Hammer M, Frier B (2009) Management of severe hypoglycaemia: cultural similarities, differences and resource consumption in three European countries. J Med Econ 12(4):269–280. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696990903310501

Brackenridge A, Wallbank H, Lawrenson R, Russell-Jones D (2006) Emergency management of diabetes and hypoglycaemia. Emerg Med J 23(3):183–185. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2005.026252

Ginde A, Pallin D, Camargo C (2008) Hospitalization and discharge education of emergency department patients with hypoglycemia. Diabetes Educ 34(4):683–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721708321022

Leese G, Wang J, Broomhall J et al (2003) Frequency of severe hypoglycemia requiring emergency treatment in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a population-based study of health service resource use. Diabetes Care 26(4):1176–1180. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.4.1176

Braatvedt G, Sykes J, Panossian Z, McNeill D (2014) The clinical course of patients with type 2 diabetes presenting to the hospital with sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycemia. Diabetes Technol Ther 16(10):661–666. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2014.0024

American Diabetes Association (2004) Hospital admission guidelines for diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:s103–s103

American Diabetes Association (2018) Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 41:55–65

Daniels A, White M, Stander I, Crone D (1999) Ambulance visits for severe hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated diabetes. N Z Med J 112:225–228

Majumdar S, Hemmelgarn B, Lin M, McBrien K, Manns B, Tonelli M (2013) Hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization and adverse events in older people: population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 36(11):3585–3590. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0523

Zoungas S, Patel A, Chalmers J et al (2010) Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med 363(15):1410–1418. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1003795

Kosiborod M, Inzucchi S, Goyal A et al (2009) Relationship between spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 301(15):1556–1564. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.496

Walker A, James C, Bannister M, Jobes E (2006) Evaluation of a diabetes referral pathway for the management of hypoglycaemia following emergency contact with the ambulance service to a diabetes specialist nurse team. Emerg Med J 23(6):449–451. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2005.028548

Duncan E, Fitzpatrick D (2016) Improving self-referral for diabetes care following hypoglycaemic emergencies: a feasibility study with linked patient data analysis. BMC Emerg Med 16:30

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1997) Hypoglycemia in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes 46(2):271–286. https://doi.org/10.2337/diab.46.2.271

Gerstein H, Miller M, Byington R et al (2008) The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358(24):2545–2559. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0802743

Gold A, Macleod K, Frier B (1994) Frequency of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 17(7):697–703. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.17.7.697

Clarke W, Cox D, Gonder-Frederick L, Julian D, Schlundt D, Polonsky W (1995) Reduced awareness of hypoglycemia in adults with IDDM. A prospective study of hypoglycemic frequency and associated symptoms. Diabetes Care 18(4):517–522. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.18.4.517

Wang H, Donnan P, Leese C et al (2017) Temporal changes in frequency of severe hypoglycemia treated by emergency medical services in types 1 and 2 diabetes: a population-based data-linkage cohort study. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 3:8

Pramming S, Thorsteinsson B, Bendtson I, Binder C (1991) Symptomatic hypoglycaemia in 411 type 1 diabetic patients. Diabet Med 8(3):217–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.1991.tb01575.x

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for their time and Ambulance Victoria for access to their data warehouse. We also acknowledge the Australian Diabetes Society for the funding support.

Funding

MV is supported by an Australian Postgraduate Scholarship. BdC is supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship. SZ is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship. This project received funding from the Australian Diabetes Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contribution to the study conception and design, data acquisition or analysis and interpretation and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript. All authors give final approval of the version to be published. MV, AE and SZ are responsible for this work as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM

(PDF 354 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Villani, M., Earnest, A., Smith, K. et al. Outcomes of people with severe hypoglycaemia requiring prehospital emergency medical services management: a prospective study. Diabetologia 62, 1868–1879 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4933-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4933-y