Abstract

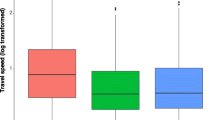

To date, animal movement studies have mostly analysed the movement behaviours of individuals at specific times of their lives, but we lack detailed information on how individual movements may be affected by the various and different changes that individuals experience throughout their life (e.g. life history phases, experience, age). Here, we attempt to identify differences in home range and movement behaviour between two different statuses, disperser vs. breeder, of a long-lived species (the eagle owl Bubo bubo). Information on home range and movement behaviour between different stages of an individual life are crucial for species conservation and management, as well as for basic knowledge on space use and rhythm of activity. Does the transition from an exploratory stage to moving within more familiar surroundings call for changes in the movement behaviour? We observed notable differences during the two stages of the owls’ lives, with individuals having different home range behaviours and rhythms of activity depending on their social status. Significant differences in home range behaviour between the sexes began only with the acquisition of a breeding site. Breeders showed larger home ranges than dispersing individuals, although nightly variation of home ranges size was higher for dispersers than for breeders. Finally, dispersers were active throughout the night, whereas breeders displayed a less active movement phase at both the beginning and end of the night. Our results demonstrate it is important to consider individual variations in space use and movement behaviour due to the different life history phases that they attain during their lifetime. The knowledge of the different needs of a species across life stages may represent an important tool for species conservation because each phase of an individual life may need different requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alerstam T (2006) Conflicting evidence about long-distance animal navigation. Science 313:791–794

Anderson DP, Forester JD, Turner MG, Frair JL, Merrill EH, Fortin D, Mao JS, Boyce MS (2005) Factors influencing female home range sizes in elk (Cervus elaphus) in North American landscapes. Landsc Ecol 20:257–271

Andersson M (1981) On optimal predator search. Theor Popul Biol 19:58–86

Barraquand F, Benhamou S (2008) Animal movements in heterogeneous landscapes: identifying profitable places and homogeneous movement bouts. Ecology 89:3336–3348

Barraquand F, Murrell DJ (2012) Evolutionarily stable consumer home range size in relation to resource demography and consumer spatial organization. Theor Ecol 5:567–589

Bates D, Maechler M (2009) lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models using S4 Classes. Version 0.999375-31. http://lme4.r-forge.r-project.org/

Berger-Tal O, Avgar T (2012) The glass is half-full: overestimating the quality of a novel environment is advantageous. PLoS One 7:e34578

Bettega C, Campioni L, Delgado MM, Lourenço R, Penteriani V (2013) Brightness features of visual signaling traits in young and adult Eurasian eagle-owls. J Raptor Res 47:197–207

Börger L, Franconi N, Ferretti F, Meschi F, De Michele G, Gantz A, Coulson T (2006) An integrated approach to identify spatiotemporal and individual-level determinants of animal home range size. Am Nat 168:471–485

Borger L, Dalziel BD, Fryxell JM (2008) Are there general mechanism of animal home range behavior? A review and prospects for future research. Ecol Lett 11:637–650

Calenge C (2006) The package adehabitat for the R software: tool for the analysis of space and habitat use by animals. Ecol Model 197:1035

Campioni L, Delgado MM, Penteriani V (2010) Social status influences microhabitat selection: breeder and floater Eagle Owls Bubo bubo use different post sites. Ibis 152:569–579

Campioni L, Lourenço R, Delgado MM, Penteriani V (2012) Breeders and floaters use different habitat cover: should habitat use be a social status-dependent strategy? J Ornithol 153:1215–1223

Campioni L, Delgado MM, Lourenço R, Bastianelli G, Fernández N, Penteriani V (2013) Individual and spatio-temporal variations in the home range behaviour of a long-lived, territorial species. Oecologia 172:371–385

Crawley MJ (2007) The R Book. J. Wiley

Dall SRX, Houston AI, McNamara JM (2004) The behavioural ecology of personality: consistent individual differences from an adaptive perspective. Ecol Lett 7:734–739

Dall SRX, Giraldeau LA, Olsson O, McNamara JM, Stephens DW (2005) Information and its use by animals in evolutionary ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 20:187–193

De Solla SR, Bonduriansky R, Brooks RJ (1999) Eliminating autocorrelation reduces biological relevance of home range estimates. J Anim Ecol 68:221–234

Delgado MM, Penteriani V (2007) Vocal behaviour and neighbour spatial arrangement during vocal displays in Eagle owl (Bubo bubo). J Zool 271:3–10

Delgado MM, Penteriani V (2008) Behavioral states help translate dispersal movements into spatial distribution patterns of floaters. Am Nat 172:475–485

Delgado MM, Penteriani V, Nams VO, Campioni L (2009) Changes of movement patterns from early dispersal to settlement. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 64:35–43

Delgado MM, Penteriani V, Revilla E, Nams VO (2010) The effect of phenotypic traits and external cues on natal dispersal movements. J Anim Ecol 79:620–632

Dingemanse NJ, Christiaan B, van Noordwijk AJ, Rutten AL, Drent PJ (2003) Natal dispersal and personalities in great tits (Parus major). Proc R Soc Lond B 270:741–747

Elkie P, Rempel R, Carr A (1999) Patch analyst user’s manual: a tool for quantifying landscape structure. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Northwest Science and Technology. http://flash.lakeheadu.ca/_rrempe/patch/

Fagan WF, Lewis MA, Auger-Méthé M, Avgar T, Benhamou S, Breed G, La Dage L, Schlägel UE, Tang W, Papastamatiou YP, Forester J, Mueller T (2013) Spatial memory and animal movement. Ecol Lett 16:1316–1329

Fauchald P, Tveraa T (2006) Hierarchical patch dynamics and animal movement pattern. Oecologia 149:383–395

Frair JL, Merrill EH, Allen JR, Boyce MS (2007) Know thy enemy: experience affects elk translocation success in risky landscapes. J Wildl Manag 71:541–554

Fraser DF, Gilliam JF, Daley MJ, Le AN, Skalski GT (2001) Explaining leptokurtic movement distributions: intrapopulation variation in boldness and exploration. Am Nat 158:124–135

Fryxell JM, Mosser A, Sinclair ARE, Packer C (2007) Group formation stabilizes predator–prey dynamics. Nature 449:1041–1044

González LM, Oria J, Sánchez R, Margalida A, Aranda A, Prada L, Caldera J, Molina JI (2008) Status and habitat changes in the endangered Spanish Imperial Eagle Aquila adalberti population during 1974–2004: implications for its recovery. Bird Conserv Int 18:242–259

Gurarie E, Bracis C, Delgado MM, Meckley T, Kojola I, Wagner M (submitted) What is the animal doing? Tools and principles for the behavioral analysis of animal movements

Haydon DT, Morales JM, Yott A, Jenkins DA, Rosatte R, Fryxell JM (2008) Socially informed random walks: incorporating group dynamics into models of population spread and growth. Proc R Soc Lond B 275:1101–1109

Holyoak M, Casagrandi R, Nathan R, Revilla E, Spiegel O (2008) Trends and missing parts in the study of movement ecology. PNAS USA 105:19060–19065

Hooge PN, Eichenlaub B (2000) Animal movement extension to ArcView, version 2.0.3. Biological Science Centre, US Geological Survey, Anchorage, Alaska

Jetz W, Carbone C, Fulford J, Brown JH (2004) The scaling of animal space use. Science 306:266–268

Kie JG, Bowyer RT, Nicholson MC, Boroski BB, Loft ER (2002) Landscape heterogeneity at differing scales: effects on spatial distribution of mule deer. Ecology 83:530–544

Lomnicki A (1988) Population ecology of individuals. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Lourenço R, Delgado MM, Campioni L, Korpimäki E, Penteriani V (submitted) Evaluating the influence of diet-related variables on breeding performance and home range behaviour of a top predator

Macdonald DW (1983) The ecology of carnivore social behaviour. Nature 301:379–384

Martin J, Calenge C, Quenette P-Y, Allainé D (2008) Importance of movement constraints in habitat selection studies. Ecol Model 213:257–262

Martin J, van Moorter B, Revilla E, Blanchard P, Dray S, Quenette P-Y, Allainé D, Swenson JE (2012) Reciprocal modulation of internal and external factors determines individual movements. J Anim Ecol 82:290–300

McLoughlin PD, Ferguson SH (2000) A hierarchical pattern of limiting factors helps explain variation in home range size. Ecoscience 7:123–130

Moorcroft PR, Lewis MA, Crabtree RL (2006) Mechanistic home range models capture spatial patterns and dynamics of coyote territories in Yellowstone. Proc R Soc Lond B 273:1651–1659

Morales JM, Fortin D, Frair JL, Merrill EH (2005) Adaptive models for large herbivore movements in heterogeneous landscapes. Landsc Ecol 20:301–316

Morales JM, Moorcroft PR, Matthiopoulos J, Frair JL, Kie JG, Powell RA, Merrill EH, Haydon DT (2010) Building the bridge between animal movement and population dynamics. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 365:2289–2301

Morellet N, Bonenfant C, Borger L, Ossi F, Cagnacci F, Heurich M, Kjellander P, Linnell JDC, Nicoloso S, Sustr P, Urbano F, Mysterud A (2013) Seasonality, weather and climate affect home range size in roe deer across a wide latitudinal gradient within Europe. J Anim Ecol 82:1326–1339

Nathan R, Giuggioli L (2013) A milestone for movement ecology research. Mov Ecol 1:1

Nathan R, Getz WM, Revilla E, Holyoak M, Kadmon R, Saltze D, Smouse PE (2008) A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal research. PNAS USA 105:19052–19059

Papastamatiou YP, Cartamil DP, Lowe CG, Meyer CG, Wetherbee BM, Holland KN (2011) Scales of orientation, directed walks and movement path structure in sharks. J Anim Ecol 80:864–874

Patterson TA, Thomas L, Wilcox C, Ovaskainen O, Matthiopoulos J (2008) State–space models of individual animal movement. Trends Ecol Evol 23:87–94

Penteriani V (2002) Variation in the function of Eagle Owl vocal behaviour: territorial defence and intra-pair communication? Ethol Ecol Evol 14:275–281

Penteriani V, Delgado MM (2011) Birthplace-dependent dispersal: are directions of natal dispersal determined a priori? Ecography 34:729–737

Penteriani V, Delgado MM (2012) There is a limbo under the moon: what social interactions tell us about the floaters’ underworld. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 66:317–327

Penteriani V, Delgado MM, Maggio C, Aradis A, Sergio F (2005) Development of chicks and predispersal behaviour of young in the Eagle Owl Bubo bubo. Ibis 147:155–168

Penteriani V, Alonso-Alvarez C, Delgado MM, Sergio F (2007) The importance of visual cues for nocturnal species: eagle owls signal by badge brightness. Behav Ecol 18:143–147

Penteriani V, Delgado MM, Maggio C, Alonso-Alvarez C, Holloway GJ (2008) Owls and rabbits: selective predation against substandard individuals by a sit-and-wait predator. J Avian Biol 39:215–221

Penteriani V, Delgado MM, Campioni L, Lourenço R (2010) Moonlight makes owls more chatty. PLoS One 5:e8696

Penteriani V, Ferrer M, Delgado MM (2011a) Floater strategies and dynamics in birds, and their importance in conservation biology: towards an understanding of nonbreeders in avian populations. Anim Conserv 14:233–241

Penteriani V, Kuparinen A, Delgado MM, Lourenço R, Campioni L (2011b) Individual status, foraging effort and need for conspicuousness shape behavioural responses of a predator to moon phases. Anim Behav 82:413–420

Pinheiro JC, Bates DM (2004) Mixed-effects Models in S and S-PLUS. Springer, New York

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, the R Core team (2009) nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-96. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org

Potts JR, Harris S, Giuggioli L (2013) Quantifying behavioural changes in territorial animals caused by sudden population declines. Am Nat 182:E73–E82

R Development Core Team (2009) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org

Rieucau G, Giraldeau LA (2011) Exploring the costs and benefits of social information use: an appraisal of current experimental evidence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 366:949–957

Rutz C, Whittingham MJ, Newton I (2006) Age-dependent diet choice in an avian top predator. Proc R Soc Lond B 273:579–586

Saarenmaa H, Stone ND, Folse LJ, Packard JM, Grant WE, Makela ME, Coulson RN (1988) An artificial intelligence modeling approach to simulating animal/habitat interaction. Ecol Model 44:125–141

Sasha RX, Houston AI, McNamara JM (2004) The behavioural ecology of personality: consistent individual differences from adaptive perspective. Ecol Lett 7:734–739

Schick RS, Loarie SR, Colchero F, Best BD, Boustany A, Conde DA, Halpin PN, Joppa LN, McClellan CM, Clark JS (2008) Understanding movement data and movement processes: current and emerging directions. Ecol Lett 11:1338–1350

Schoener TW (1983) Field experiments on interspecific competition. Am Nat 122:240–285

Seaman DE, Powell RA (1996) An evaluation of the accuracy of Kernel density estimators for home range analysis. Ecology 77:2075–2085

Seaman DE, Millspaugh JJ, Kernohan BJ, Brundige GC, Raedeke KJ, Gitzen RA (1999) Effects of sample size on kernel home range estimates. J Wildl Manag 63:739–747

Silverman BW (1986) Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. Chapman and Hall

Smouse PE, Focardi S, Moorcroft PR, Kie JG, Forester JD, Morales JM (2010) Stochastic modelling of animal movement. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 365:2201–2211

Stamps JA (1995) Motor learning and home range value. Am Nat 146:41–58

Stamps JA, Groothuis GG (2010) Developmental perspectives on personality: implications for ecological and evolutionary studies of individual differences. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 365:4029–4041

Stamps JA, Krishnan VV (1999) A learning-based model of territory establishment. Q Rev Biol 74:291–318

Thield A, Hoffmeister TS (2004) Knowing your habitat: linking patch encounter rate and patch exploitation in parasitoids. Behav Ecol 15:419–425

Vos M, Hemerik L, Vet LEM (1998) Patch exploitation by parasitoids Cotesia rebecula and Cotesia glomerata in multi-patch environments with different host distributions. J Anim Ecol 48:353–371

Vuilleumier S, Perrin N (2006) Effects of cognitive abilities on metapopulation connectivity. Oikos 113:139–147

Worton BJ (1989) Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home range studies. Ecology 70:164–168

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Bartolommei, C. Bettega and R. Lourenço for their help during radiotracking. The research adheres to the legal requirements of the country where it has been carried out. We manipulated and marked owls under Junta de Andalucía-Consejería de Medio Ambiente authorizations No. SCFFS-AFR/GGG RS-260/02 and SCFFS-AFR/CMM RS-1904/02. The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (CGL2012–33240; FEDER co-financing).

Conflict of interest

The manipulation of individuals (trapping and radiotagging) described in this paper comply with the current laws of the country in which they were performed. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by: Sven Thatje

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Penteriani, V., del Mar Delgado, M. & Campioni, L. Quantifying space use of breeders and floaters of a long-lived species using individual movement data. Sci Nat 102, 21 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-015-1271-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-015-1271-x