Abstract

Background

Music is one of the most commonly used non-pharmacological interventions to reduce anxiety. It helps patients overcome emotional and physical alienation, provides comfort and familiarity in an improved environment and offers a pleasant distraction from pain and anxiety. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of listening to preoperative favorite music on postoperative anxiety and pain.

Material and methods

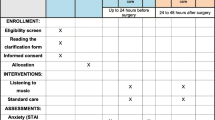

This prospective, randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial included the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I–III patients, aged 18–70 years, undergoing elective inguinal hernia surgery. Demographic data and anxiety status were recorded. Anxiety status was measured using the Spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory form 1 (STAI-1) and state-trait anxiety inventory form 2 (STAI-2). After recording baseline heart rate, blood pressure and STAI levels, patients were randomly allocated to the music group (Group M) or control group (Group C). Patients in Group M listened to their favorite music using headphones and patients in the control group received standard care. The STAI‑1 was repeated after surgery and the numeric rating scale (NRS) and patient satisfaction were measured.

Results

A total of 117 patients were included. Demographic data, educational status, and previous surgical history were similar between the groups. Mean preoperative STAI‑1 and STAI‑2 scores were similar between the groups (p > 0.05). Mean postoperative STAI‑1 score was significantly lower in Group M than in Group C (39 [range 35–43] vs. 41 [range 37–43], p < 0.05). Moreover, the change in the STAI score was significantly higher in Group M compared with Group C (p < 0.05). The difference of hemodynamic measurements pre-music to post-music was significant between Group M and Group C (p = 0.001). The NRS scores remained similar between the groups. Patient satisfaction score was significantly higher in Group M (p = 0.017).

Conclusion

Listening to patient-preferred favorite music preoperatively reduced anxiety, regulated hemodynamic parameters, and improved postoperative patient satisfaction. Reduced anxiety was not associated with reduced pain.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Musik ist eine der am häufigsten angewendeten nicht-pharmakologischen Interventionen zur Reduzierung von Angstzuständen. Sie hilft Patienten, emotionale und physische Entfremdungen zu überwinden, bietet Komfort und Vertrautheit in einer angenehmen Umgebung und lenkt wohltuend von Schmerz und Angst ab. In der aktuellen Studie sollten die Auswirkungen des präoperativen Hörens von „Lieblingsmusik“ auf die postoperative Angst und den Schmerz untersucht werden.

Materialien und Methoden

In diese prospektiv-randomisierte, einfach verblindete, kontrollierte Studie wurden Amerikanische Gesellschaft für Anästhesisten(ASA)-I- bis -III-Patienten im Alter von 18 bis 70 Jahren einbezogen, die sich einer elektiven Leistenbruchoperation unterzogen. Demografische Daten und Angstzustände wurden erfasst. Der Angststatus wurde unter Verwendung der Formulare 1 (STAI-1) und 2 (STAI-2) des Spielberger-Staats-Trait-Angstinventars gemessen. Nach Aufzeichnung von Herzfrequenz‑, Blutdruck- und STAI-Ausgangswerten wurden die Patienten nach dem Zufallsprinzip der Musikgruppe (Gruppe M) oder der Kontrollgruppe (Gruppe C) zugeordnet. Patienten der Gruppe M hörten ihre Lieblingsmusik mit Kopfhörern und Patienten der Kontrollgruppe erhielten eine Standardversorgung ohne Musik. STAI‑1, der NRS-Score und die Zufriedenheit wurden postoperativ gemessen.

Ergebnisse

Insgesamt wurden 117 Patienten in die Studie eingeschlossen. Demografische Daten, Bildungshintergrund und Operationsvorgeschichte waren in den Gruppen ähnlich. Die mittleren präoperativen STAI-1- und STAI-2-Scores waren zwischen den Gruppen ähnlich (p > 0,05). Der mittlere postoperative STAI-1-Score war in Gruppe M signifikant niedriger als in Gruppe C (39 [35–43] vs. 41 [37–43]; p < 0,05). Darüber hinaus war die Veränderung des STAI-Scores in Gruppe M signifikant höher als in Gruppe C (p = 0,001). Die Veränderung der hämodynamischen Messungen vor bis nach der Musik war zwischen Gruppe M und Gruppe C signifikant (p = 0,001). Die der numerische Rating-Skala (NRS) waren zwischen den Gruppen ähnlich. Die Zufriedenheit der Patienten war in der M-Gruppe signifikant höher (p = 0,017).

Diskussion

Das Hören von Lieblingsmusik reduziert die Angst, reguliert hämodynamische Parameter und verbessert die postoperative Patientenzufriedenheit. Eine verminderte Angst war nicht mit verminderten Schmerzen verbunden.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jlala HA, French JL, Foxall GL, Hardman JG, Bedforth NM (2010) Effect of preoperative multimedia information on perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing procedures under regional anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 104(3):369–374

Lin CJ, Liu HP, Wang PY, Yu MH, Lu MC, Hsieh LY, Lin TC (2019) The effectiveness of preoperative preparation for improving perioperative outcomes in children and caregivers. Behav Modif 43(3):311–329

McClurkin SL, Smith CD (2016) The duration of self-selected music needed to reduce preoperative anxiety. J Perianesth Nurs 31(3):196–208

Bradt J, Dileo C, Shim M (2013) Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD6908

O’Regan P, Wills T (2009) The growth of complementary therapies: and their benefits in the perioperative setting. J Perioper Pract 19(11):382–386

Wright KD, Stewart SH, Finley GA, Buffett-Jerrott SE (2007) Prevention and intervention strategies to alleviate preoperative anxiety in children: a critical review. Behav Modif 31(1):52–79

Palmer JB, Lane D, Mayo D, Schluchter M, Leeming R (2015) Effects of music therapy on anesthesia requirements and anxiety in women undergoing ambulatory breast surgery for cancer diagnosis and treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33(28):3162–3168

Uğraş GA, Yıldırım G, Yüksel S, Öztürkçü Y, Kuzdere M, Öztekin SD (2018) The effect of different types of music on patients’ preoperative anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract 31:158–163

Kipnis G, Tabak N, Koton S (2016) Background music playback in the preoperative setting: Does it reduce the level of preoperative anxiety among candidates for elective surgery? J Perianesth Nurs 31(3):209–216

Spielberger CDGR, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA (1983) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Öner NLCA (1985) Durumluk sürekli kaygı envanteri el kitabı İstanbul. Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

Arslan ÖSN, Özyurt F (2008) Effect of music on preoperative anxiety in men undergoing urogenital surgery. Aust J Adv Nurs 26:46–54

Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, Ihde-Scholl T, Scheidegger D (2000) The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients’ anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg 90(3):706–712

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41(4):1149–1160

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2):175–191

Taşdemir A, Erakgün A, Deniz MN, Çertuğ A (2013) Comparison of preoperative and postoperative anxiety levels with State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Test in preoperatively informed patients. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim 41:44–49

Nilsson U (2008) The anxiety- and pain-reducing effects of music interventions: a systematic review. AORN J 87(4):780–807

Shabanloei R, Golchin M, Esfahani A, Dolatkhah R, Rasoulian M (2010) Effects of music therapy on pain and anxiety in patients undergoing bone marrow biopsy and aspiration. AORN J 91(6):746–751

Firmeza MA, Rodrigues AB, Melo GA, Aguiar MI, Cunha GH, Oliveira PP, Grangeiro AS (2017) Control of anxiety through music in a head and neckoutpatient clinic: a randomized clinical trial. Rev Esc Enferm USP 51:e3201

Koelsch S, Fuermetz J, Sack U, Bauer K, Hohenadel M, Wiegel M, Kaisers UX, Heinke W (2011) Effects of music listening on cortisol levels and propofol consumption during spinal anesthesia. Front Psychol 2:58

Ebneshahidi A, Mohseni M (2008) The effect of patient-selected music on early postoperative pain, anxiety, and hemodynamic profile in cesarean section surgery. J Altern Complement Med 14(7):827–831

Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C (2015) Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 386(10004):1659–1671

Ruud E (2013) Can music serve as a “cultural immunogen”? An explorative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 8:20597

Angioli R, De Cicco Nardone C, Plotti F, Cafa EV, Dugo N, Damiani P, Ricciardi R, Linciano F, Terranova C (2014) Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 21(3):454–459

Fukui H, Toyoshima K (2013) Influence of music on steroid hormones and the relationship between receptor polymorphisms and musical ability: a pilot study. Front Psychol 4:910

Kreutz G, Bongard S, Rohrmann S, Hodapp V, Grebe D (2004) Effects of choir singing or listening on secretory immunoglobulin A, cortisol, and emotional state. J Behav Med 27(6):623–635

Amir D (1999) Musical and verbal interventions in music therapy: a qualitative study. J Music Ther 36(2):144–175

Kühlmann AYR, de Rooij A, Kroese LF, van Dijk M, Hunink MGM, Jeekel J (2018) Meta-analysis evaluating music interventions for anxiety and pain in surgery. Br J Surg 105(7):773–783

Drzymalski DM, Tsen LC, Palanisamy A, Zhou J, Huang CC, Kodali BS (2017) A randomized controlled trial of music use during epidural catheter placement on laboring parturient anxiety, pain, and satisfaction. Anesth Analg 124(2):542–547

Ozturk E, Hamidi N, Yikilmaz TN, Ozcan C, Basar H (2019) Effect of listening to music on patient anxiety and pain perception during urodynamic study: randomized controlled trial. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 11(1):39–42

Thomas T, Robinson C, Champion D, McKell M, Pell M (1998) Prediction and assessment of the severity of post-operative pain and of satisfaction with management. Pain 75(2–3):177–185

Graff V, Cai L, Badiola I, Elkassabany NM (2019) Music versus midazolam during preoperative nerve block placements: a prospective randomized controlled study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 44:796–799

Scott A (2004) Managing anxiety in ICU patients: the role of pre-operative information provision. Nurs Crit Care 9(2):72–79

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Surgical and medical practices: F.K.A., S.A., concept: F.K.A., J.E., design: F.K.A., J.E., data collection or processing: F.K.A., S.A., M.T.A, analysis or interpretation: F.K.A., S.A, J.E., literature search: F.K.A., M.T.A, writing: F.K.A., S.A., M.T.A., J.E.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

F. Kavak Akelma, S. Altınsoy, M. T. Arslan and J. Ergil declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants or on human tissue were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Ministry of Health Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey (Ethical Committee 15.10.2018 No: 55/16).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kavak Akelma, F., Altınsoy, S., Arslan, M.T. et al. Effect of favorite music on postoperative anxiety and pain. Anaesthesist 69, 198–204 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00101-020-00731-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00101-020-00731-8