Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of pediatric patients who underwent nonoperative management (NOM) for blunt splenic and hepatic injuries and to explore factors associated with NOM failure.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of a multicenter cohort study of pediatric patients with blunt liver and spleen injuries in Japan. Participants included pediatric trauma patients aged 16 years or younger between 2008 and 2019 with NOM, which was defined as no surgery provided within 6 h of hospital arrival. NOM failure, defined as abdominal surgery performed after 6 h of hospital arrival, was the primary outcome. Descriptive statistics were provided and exploratory analysis to assess the associations with outcome using logistic regression.

Results

During the study period, 1339 met our eligibility criteria. The median age was 9 years, with a majority being male. The median Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 10. About 14.0% required transfusion within 24 h, and 22.3% underwent interventional radiology procedures. NOM failure occurred in 1.0% of patients and the in-hospital mortality was 0.7%. Factors associated with NOM failure included age, positive focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST), contrast extravasation on computed tomography (CT), severe liver injury, concomitant pancreas injury, concomitant gastrointestinal injury, concomitant mesenteric injury, and ISS.

Conclusions

In our study, NOM failure were rare. Older age, positive FAST, contrast extravasation on CT, severe liver injury, concomitant pancreas injury, concomitant gastrointestinal injury, concomitant mesenteric injury, and higher ISS were suggested as possible risk factors for NOM failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries, nonoperative management (NOM) has become the preferred approach in current practice. The guidelines by the German Trauma Society recommended NOM for hemodynamically stable isolated liver and spleen injuries in children, involving close monitoring and preparation for immediate interventional radiology and/or surgical intervention [1]. Guidelines from Level I pediatric trauma centers in the United States suggest that management of pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries may be based on hemodynamic status rather than injury grade, with unstable patients considered for surgery, urgent embolization, or continued NOM, depending on other injuries and the center's resources [2]. Updated guidelines published in 2023 by the American Pediatric Surgical Association discuss patients exceeding the shock index, pediatric age-adjusted (SIPA) cutoffs, deeming them unstable and more likely to experience NOM failure [3]. However, management of pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries presents may vary among Europe and the United States in several aspects, as the indication for surgical intervention can differ based on institutional capabilities [4].

Evidence exists regarding associated factors contributing to NOM failure in pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries. A retrospective study identified NOM failure in pediatric solid organ injury associated with injury severity, presence of multiple organ injuries, and pancreatic injury [5]. Furthermore, a prospective observational study conducted at level I pediatric trauma centers demonstrated associations between NOM failure in pediatric liver and spleen injuries and contrast extravasation on computed tomography (CT), early transfusion, and injury to multiple intra-abdominal organs [6]. A previous systematic review supported that the management of liver and spleen injuries in children should include consideration of the presence of contrast extravasation on CT in addition to the physiologic response [7]. Another analysis in this study group identified that negative focused abdominal sonography for trauma examination was predictive of successful NOM of pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries [8].

However, due to the infrequent occurrence of NOM failure, there remains insufficient evidence to characterize its determinants in pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries, underscoring the necessity for individualized risk assessment. The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of pediatric patients who underwent NOM for blunt splenic and hepatic injuries and to explore factors associated with NOM failure.

Methods

Study design and setting

We performed a secondary analysis of data derived from the previously reported the Splenic and Hepatic Injury in Pediatric Patients (SHIPPs) study, which was a multicenter cohort study in pediatric patients with blunt liver and spleen injury in Japan [9, 10]. The institutional ethics committee of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine approved this study and waived the requirement for informed consent (approval no. 20129). Given the non-interventional nature of this study, the necessity for individual patient informed consent was waived for this study.

Participants

We included pediatric blunt trauma patients aged 16 years or younger with liver and splenic injury, who were enrolled in the SHIPPs study from 83 centers between 2008 and 2019 [9, 10]. We excluded patients who had cardiopulmonary arrest on arrival, an abbreviated injury scale (AIS) 6 injury of any body region, a parent or guardian refusal of treatment due to a severe head injury (head AIS 5 +), and a transfer to another hospital within 5 days of admission without required follow-up information. Attempted NOM was defined as no surgery within 6 h after hospital arrival in accordance with a previous study [11]. Therefore, we excluded those with operative management within 6 h.

Variables

We extracted the following patient data: age, sex, mechanism of injury, vital signs on hospital arrival, results of focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST), presence of contrast extravasation on CT, injury site (liver, spleen, or both), injury grade for liver and spleen according to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale grade (2018 revision), concomitant injury (AIS 3 +) to the head/neck, thorax, or pelvis/lower-extremity, concomitant intra-abdominal injury, injury severity score (ISS), transfusion administration within 24 h, need for interventional radiology, time to surgery from hospital arrival, reason for surgery, and in-hospital mortality. The presence of shock on arrival was defined using SIPA [12]. We classified liver injuries graded IV and V as severe liver injuries, and spleen injuries graded IV and V as severe spleen injuries, based on guidelines from the World Society of Emergency Surgery [13, 14]. The outcome of interest in this study was NOM failure, which was defined as abdominal surgery performed after attempted NOM over 6 h of hospital arrival.

Statistical methods

Continuous variables are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables are presented as the number and percentage. We explored the association between the NOM failure and relevant variables including age, sex, shock on arrival, positive FAST, contrast extravasation on CT, liver injury grade IV or V, spleen injury grade IV or V, concomitant intra-abdominal injuries, and ISS by a univariable logistic regression analysis and calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A multivariable logistic regression analysis was planned if the outcome events were observed 20 or more to avoid the risk of overfitting and decreasing the confidence in reported findings [15]. We also described the characteristics in cases with NOM failure and in-hospital mortality. To assess changes in patients’ characteristics and outcomes over time, we divided the research period into early (2008–2013) and late (2014–2019) time periods, then repeated the same analyses. We used Mann–Whitney U test or chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction to compare these two time periods as needed.

All tests were two-tailed, and P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 3.6.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

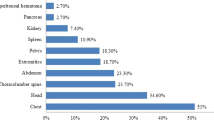

Results

During the study period, the SHIPPs database recorded 1462 pediatric patients with blunt liver and spleen injuries, of which 1339 met our eligibility criteria, as shown in Fig. 1. Characteristics of 83 participating centers were shown in Table S1. In most participating centers, surgeons and interventional radiologists were available whenever needed (89.2% and 80.7%, respectively), while in the remaining centers, their availability was limited. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these eligible patients. The median age was 9 years (IQR, 6 to 13) and more than half were male (66.5%). The most common injury mechanisms were pedestrian accidents (24.2%), falls from height or down stairs (22.2%), and bicycle crashes (19.1%). Liver injury was observed in 62.4% of patients, spleen injury in 40.9%, and both liver and spleen injuries in 3.2% of cases. Concomitant kidney injury occurred in 9.5% of patients, pancreas injury in 2.2%, gastrointestinal injury in 0.9%, and mesenteric injury in 0.3%. The median ISS was 10 (IQR, 5 to 18), 14.0% required blood transfusion within 24 h of hospital arrival, and 22.3% underwent interventional radiology procedures. Overall, 1.0% of patients experienced NOM failure, while the in-hospital mortality was 0.7%.

Table 2 presents the results of univariate logistic regression analyses, indicating the odds ratios of each variable for NOM failure. Factors associated with NOM failure included age, positive FAST, contrast extravasation on CT, liver injury grade IV or V, concomitant pancreas injury, concomitant gastrointestinal injury, concomitant mesenteric injury, and ISS. Due to the limited number of outcomes, multivariable analysis was not conducted according to the initial plan.

Table 3 outlines the characteristics of the 13 patients who experienced NOM failure. Among them, 30.8% presented with shock upon hospital arrival, while 46.2% exhibited contrast extravasation on CT scans. Out of 13 patients with NOM failure, 10 patients (76.9%) had liver injury, 4 (30.8%) had spleen injury and 1 (7.7%) had both. Interventional radiology was required for 76.9% of these cases. The median time from hospital arrival to surgery was 20 h (IQR, 10 to 123.5), with active bleeding being the most common reason for surgical intervention (53.8%). Of these 7 cases of NOM failure due to active bleeding, 4 underwent interventional radiology as the initial intervention. In-hospital mortality among NOM failure cases stood at 15.4%, with 2 out of the 13 cases of NOM failure. The causes of death in both cases were hemorrhagic shock due to liver/spleen injury, with one case also indicating traumatic brain injury as an additional cause of death. Table 4 summarizes patient characteristics in the 10 cases resulting in in-hospital mortality, with traumatic brain injury identified as the primary cause of death in 70.0% of cases. We did not see significant changes in patients’ characteristics between the early (2008–2013) and late (2014–2019) time periods (Table S2). Proportions of interventional radiology and NOM failure did not significantly change over time in our study.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the characteristics of pediatric patients who underwent NOM for blunt liver and spleen injuries, as well as explored factors associated with NOM failure. We observed a low incidence of NOM failure among pediatric patients with blunt liver and spleen injuries with only 1.0% of patients experiencing NOM failure, suggesting that NOM is a safe and effective approach for the majority of pediatric patients with these injuries, as demonstrated in previous literature [5, 6, 16]. In our study, we identified several potential risk factors associated with NOM failure in pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries, including older age, positive FAST, contrast extravasation on CT, severe liver injury, concomitant pancreas injury, concomitant gastrointestinal injury, concomitant mesenteric injury, and higher ISS. Although our findings necessitate further investigation, they could help identifying patients at risk of NOM failure and determining the optimal timing for surgical intervention.

While some of these factors were consistent with previous literature, others showed discrepancies. While previous study on factors associated with NOM failure in pediatric blunt abdominal injury suggested NOM failure was not associated with age but was associated with pancreatic injury, both older age and concomitant pancreas injury were associated with higher incidence of NOM failure in our study [17]. Another cohort study showed that negative FAST and negative SIPA in the emergency department could be predictive of successful NOM of pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries [8]. In our study, a positive FAST was associated with NOM failure, consistent with previous findings, while shock on arrival using SIPA was not associated with NOM failure. This discrepancy may arise from successful resuscitation in some cases upon arrival, with most NOM failure cases not presenting with shock initially but developing it later. Alternatively, reasons for surgery in NOM failure cases may not necessarily be due to active bleeding. Contrast extravasation on CT was also associated with NOM failure, as suggested in a previous systematic review [7]. A previous study found minimal transition to surgery or interventional radiology when contrast extravasation is detected, with nonoperative treatment success prevailing [18]. However, the authors of this study cautioned that overall clinical assessment remains crucial in determining the need for intervention.

Severe liver injury was associated with NOM failure, while severe spleen injury was not associated in our study. This could be attributed to the recommendation of angioembolization as an alternative to splenectomy in pediatric spleen injury, as outlined in guidelines [1, 2, 19]. Most patients with NOM failure had liver injury in our study, including one patient with bile leak/biloma as a reason for surgery. Prior single-center retrospective observational studies have indicated high success rates of NOM in pediatric blunt liver injuries, regardless of the grade [20, 21]. However, our study's findings suggest the need for caution when considering NOM for high-grade liver injuries. Previous literature indicated that factors such as ISS, multiplicity of injured organs, and pancreatic injuries were associated with NOM failure in pediatric solid organ injury [5]. This literature also highlighted common reasons for NOM failure, including peritonitis and hollow organ injury, as well as shock and persistent hemorrhage. Our study yielded similar results, although concomitant kidney injury was not associated with NOM failure. The distribution of reasons for surgery or NOM failure was similar as well. Based on the proportions of transfusion administration within 24 h and interventional radiology performed in our study, these procedures were successfully provided to hemodynamically stabilize as described in guidelines [1,2,3, 6].

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, the SHIPPs study was a multicenter retrospective cohort study that did not use a specific protocol for treatment strategies for pediatric trauma. As reported in previous studies, there may be variation in treatment strategies from facility to facility and even within facilities, which may have affected the results [22, 23]. Second, NOM failure was rare, and although this was a multicenter study, NOM failure was only 0.8%, so multivariate analysis was not possible. In addition, the results may not be generalizable due to differences in emergency systems, such as accessibility to CT scans and angiography in trauma care. Our findings may reflect these unique Japanese practice patterns diverging from the European and American standards, emphasizing the need to consider these differences when interpreting the results. Although surgeons and interventional radiologists were available anytime needed in most participating centers, centers with limited access to interventional radiology may be more inclined towards operative management, potentially impacting the outcomes of NOM. While we were unable to conduct multivariable analysis to adjust for confounding, directing attention towards these potential associated factors, alongside close hemodynamic monitoring, may be valuable during NOM in pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries.

Conclusions

Among pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries who underwent NOM, cases of NOM failure were rare. In our study, older age, positive FAST, contrast extravasation on CT, severe liver injury, concomitant pancreas injury, concomitant gastrointestinal injury, concomitant mesenteric injury, and higher ISS were suggested as possible risk factors for NOM failure. In addition to close hemodynamic monitoring during NOM in pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries, focusing on these factors may be valuable to improve pediatric trauma care.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the SHIPPs study group, but the availability of these data is restricted.

References

Polytrauma Guideline Update Group. Level 3 guideline on the treatment of patients with severe/multiple injuries. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44(Suppl 1):S3–271.

Notrica DM, Eubanks JW, Tuggle DW, Maxson RT, Letton RW, Garcia NM, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt liver and spleen injury in children: Evaluation of the ATOMAC guideline using GRADE. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:683–93.

Williams RF, Grewal H, Jamshidi R, Naik-Mathuria B, Price M, Russell RT, et al. Updated APSA Guidelines for the Management of Blunt Liver and Spleen Injuries. J Pediatr Surg. 2023;58:1411–8.

Harwood R, Bethell G, Eastwood MP, Hotonu S, Allin B, Boam T, et al. The Blunt Liver and Spleen Trauma (BLAST) audit: national survey and prospective audit of children with blunt liver and spleen trauma in major trauma centres. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2023;49:2249–56.

Holmes JH IV, Wiebe DJ, Tataria M, Mattix KD, Mooney DP, Scaife ER, et al. The failure of nonoperative management in pediatric solid organ injury: A multi-institutional experience. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 2005;59:1309–13.

Linnaus ME, Langlais CS, Garcia NM, Alder AC, Eubanks JW, Todd Maxson R, et al. Failure of nonoperative management of pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries: A prospective Arizona-Texas-Oklahoma-Memphis-Arkansas Consortium study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:672–9.

van der Vlies CH, Saltzherr TP, Wilde JCH, van Delden OM, de Haan RJ, Goslings JC. The failure rate of nonoperative management in children with splenic or liver injury with contrast blush on computed tomography: a systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1044–9.

McGaha P, Motghare P, Sarwar Z, Garcia NM, Lawson KA, Bhatia A, et al. Negative focused abdominal sonography for trauma examination predicts successful nonoperative management in pediatric solid organ injury: A prospective Arizona-Texas-Oklahoma-Memphis-Arkansas + Consortium study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86:86–91.

Katsura M, Kondo Y, Yasuda H, Fukuma S, Matsushima K, Shiraishi A, et al. Therapeutic strategies for pseudoaneurysm following blunt liver and spleen injuries: A multicenter cohort study in the pediatric population. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;94:433–42.

Katsura M, Fukuma S, Kuriyama A, Kondo Y, Yasuda H, Matsushima K, et al. Association of Contrast Extravasation Grade With Massive Transfusion in Pediatric Blunt Liver and Spleen Injuries: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. J Pediatr Surg. 2024;59:500–8.

Polanco PM, Brown JB, Puyana JC, Billiar TR, Peitzman AB, Sperry JL. The swinging pendulum: A national perspective of nonoperative management in severe blunt liver injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:590–5.

Nordin A, Coleman A, Shi J, Wheeler K, Xiang H, Acker S, et al. Validation of the age-adjusted shock index using pediatric trauma quality improvement program data. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:130–5.

Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Ordonez C, Kluger Y, Vega F, Moore EE, et al. Liver trauma: WSES 2020 guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15(1):24.

Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Moore EE, et al. Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:1–26.

Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–8.

Spijkerman R, Bulthuis LCM, Hesselink L, Nijdam TMP, Leenen LPH, de Bruin IGJM. Management of pediatric blunt abdominal trauma in a Dutch level one trauma center. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2021;47:1543–51.

Tataria M, Nance ML, Holmes JH, Miller C, Mattix KD, Brown RL, et al. Pediatric blunt abdominal injury: Age is irrelevant and delayed operation is not detrimental. J Trauma. 2007;63:608–14.

Ingram MCE, Siddharthan RV, Morris AD, Hill SJ, Travers CD, McKracken CE, et al. Hepatic and splenic blush on computed tomography in children following blunt abdominal trauma: Is intervention necessary? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:266–70.

Olthof DC, Van Der Vlies CH, Joosse P, Van Delden OM, Jurkovich GJ, Goslings JC. Consensus strategies for the nonoperative management of patients with blunt splenic injury: A Delphi study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:1567–74.

Nellensteijn D, Porte RJ, Van Zuuren W, Ten Duis HJ, Hulscher JBF. Paediatric blunt liver trauma in a Dutch level 1 trauma center. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19:358–61.

Koyama T, Skattum J, Engelsen P, Eken T, Gaarder C, Naess PA. Surgical intervention for paediatric liver injuries is almost history - a 12-year cohort from a major Scandinavian trauma centre. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:1–5.

Shimizu T, Umemura T, Fujiwara N, Nakama T. Review of pediatric abdominal trauma: operative and non-operative treatment in combined adult and pediatric trauma center. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6:358–64.

Swendiman RA, Goldshore MA, Fenton SJ, Nance ML. Defining the role of angioembolization in pediatric isolated blunt solid organ injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55:688–92.

Acknowledgements

The SHIPPs study was supported by the Japanese Association for Surgery of Trauma Multicenter Trial Committee for their contributions to data collection at each institution.

The authors thank all collaborators of SHIPPs study group: Tomoya Ito (Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Aichi Children's Health and Medical Center, Aichi, Japan); Motoyoshi Yamamoto and Yoshihiro Yamamoto (Department of Emergency Medicine, Aizawa Hospital, Nagano, Japan); Hiroto Manase (Department of Surgery, Asahikawa Red Cross Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan); Nozomi Takahashi (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan); Akinori Osuka (Department of Trauma, Critical Care Medicine and Burn Center, Chukyo Hospital, Nagoya, Japan); Suguru Annen (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Ehime University Hospital, Ehime, Japan); Nobuki Ishikawa (Department of Pediatric Surgery, Fukui Prefectural Hospital, Fukui, Japan); Kazushi Takayama (Trauma, Emergency and Critical Care Center, Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan); Keita Minowa ((Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Hachinohe City Hospital, Aomori, Japan); Kenichi Hakamada (Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Hirosaki University Hospital, Aomori, Japan); Akari Kusaka (Critical Care Medical Center, Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan); Mineji Hayakawa and Shota Kawahara (Department of Emergency Medicine, Hokkaido University Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan); Satoshi Hirano (Department of Gastroenterological Surgery II, Faculty of Medicine, Hokkaido University, Hokkaido, Japan); Marika Matsumoto (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Hyogo Emergency Medical Center, Hyogo, Japan); Kohei Kusumoto (Department of Pediatric Intensive Care, Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center, Hyogo, Japan); Hiroshi Kodaira (Department of Emergency Medicine, Hyogo Prefectural Awaji Medical Center, Hyogo, Japan); Chika Kunishige (Acute Care Medical Center, Hyogo Prefectural Kakogawa Medical Center, Hyogo, Japan); Keiichiro Toma and Yusuke Seino (Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Hyogo Prefectural Kobe Children's Hospital, Hyogo, Japan); Michio Kobayashi (Department of Emergency Medicine, Ishinomaki Red Cross Hospital, Miyagi, Japan); Masaaki Sakuraya (Division of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, JA Hiroshima General Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan); Takafumi Shinjo and Shigeru Ono (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine and Department of Pediatric Surgery, Jichi Medical University Hospital, Tochigi, Japan); Hideto Yasuda and Haruka Taira (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Saitama, Japan); Kazuhiko Omori (Department of Acute Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Shizuoka Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan); Yutaka Kondo (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Chiba, Japan); Yoshio Kamimura (Department of Emergency Medicine, Kagoshima City Hospital, Kagoshima, Japan); Atsushi Shiraishi and Rei Tanaka (Emergency and Trauma Center, Kameda Medical Center, Chiba, Japan); Yukihiro Tsuzuki (Department of Pediatric Surgery, Kanagawa Children's Medical Center, Kanagawa, Japan); Yukio Sato (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Keio University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan); Noriaki Kyogoku (Department of Surgery, Kitami Red Cross Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan); Masafumi Onishi and Kaichi Kawai (Department of Emergency Medicine, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Hyogo, Japan); Kazuyuki Hayashida and Keiko Terazumi (KRC Severe Trauma Center / Trauma & Critical Care, Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Hospital, Kumamoto, Japan); Akira Kuriyama and Susumu Matsushime (Emergency and Critical Care Center, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Okayama, Japan); Osamu Takasu and Toshio Morita (Advanced Emergency Medical Service Center, Kurume University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan); Nagato Sato (Department of Surgery, Kushiro City General Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan); Wataru Ishii and Michitaro Miyaguni (Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care, Kyoto Second Red Cross Hospital, Kyoto, Japan); Shingo Fukuma (Human Health Sciences, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan); Yosuke Nakabayashi and Yoshimi Ohtaki (Advanced Medical Emergency Department and Critical Care Center, Maebashi Red Cross Hospital, Gunma, Japan); Kiyoshi Murata and Masayuki Yagi (Department of Emergency Medicine and Acute Care Surgery, Matsudo City General Hospital, Chiba, Japan); Tadashi Kaneko (Emergency and Critical Care Center, Mie University Hospital, Mie, Japan); Shigeru Takamizawa (Department of Pediatric Surgery, Nagano Children's Hospital, Nagano, Japan); Akihiro Yasui (Department of Pediatric Surgery, Nagoya University Hospital, Nagoya, Japan); Yasuaki Mayama (Department of Emergency Medicine, Nakagami Hospital, Okinawa, Japan); Masafumi Gima (Critical Care Medicine, National Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan); Ichiro Okada (Department of Critical Care Medicine and Trauma, National Hospital Organization Disaster Medical Center, Tokyo, Japan); Asuka Tsuchiya and Koji Ishigami (Department of Emergency Medicine, National Hospital Organization Mito Medical Center, Ibaraki, Japan); Yukiko Masuda (Emergency and Critical Care Center, National Hospital Organization Nagasaki Medical Center, Nagasaki, Japan); Yasuo Yamada (Department of Emergency Medicine, National Hospital Organization Sendai Medical Center, Miyagi, Japan); Hiroshi Yasumatsu (Shock and Trauma Center, Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital, Chiba, Japan); Kenta Shigeta (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Nippon Medical School Hospital, Tokyo, Japan); Kohei Kato (Department of Surgery, Obihiro Kosei Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan); Fumihito Ito (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Ohta Nishinouchi Hospital, Fukushima, Japan); Atsuyoshi Iida (Department of Emergency Medicine, Okayama Red Cross Hospital, Okayama, Japan); Tetsuya Yumoto and Hiromichi Naito (Department of Emergency, Critical Care and Disaster Medicine, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan); Morihiro Katsura and Yoshitaka Saegusa (Department of Surgery, Okinawa Chubu Hospital, Okinawa, Japan); Tomohiko Azuma (Department of Surgery, Okinawa Hokubu Hospital, Okinawa, Japan); Shima Asano (Department of Surgery, Okinawa Miyako Hospital, Okinawa, Japan); Takehiro Umemura and Norihiro Goto (Department of Emergency Medicine, Okinawa Nanbu Medical Center & Children's Medical Center, Okinawa, Japan); Takao Yamamoto (Department of Surgery, Okinawa Yaeyama Hospital, Okinawa, Japan); Junichi Ishikawa (Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Osaka City General Hospital, Osaka, Japan); Elena Yukie Uebayashi (Department of Pediatric Surgery, Osaka Red Cross Hospital, Osaka, Japan); Shunichiro Nakao (Department of Traumatology and Acute Critical Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan); Yuko Ogawa (Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Osaka Women's and Children's Hospital, Osaka, Japan); Takashi Irinoda (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Osaki Citizen Hospital, Osaka, Japan); Yuki Narumi (Senshu Trauma And Critical Care Center, Rinku General Medical Center, Osaka, Japan); Miho Asahi (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Saga University Hospital, Saga, Japan); Takayuki Ogura and Takashi Hazama (Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care Medicine, Saiseikai Utsunomiya Hospital, Tochigi, Japan); Shokei Matsumoto (Department of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, Saiseikai Yokohamashi Tobu Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan); Daisuke Miyamoto (Department of Emergency, Trauma and Critical Care Medicine, Saitama Children's Medical Center, Saitama, Japan); Keisuke Harada and Narumi Kubota (Department of Emergency Medicine, Sapporo Medical University Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan); Yusuke Konda (Department of Emergency and Critical Care, Sendai City Hospital, Miyagi, Japan); Takeshi Asai (Department of Pediatric Surgery, Shikoku Medical Center for Children and Adults, Kagawa, Japan); Tomohiro Muronoi (Department of Acute Care Surgery, Shimane University Hospital, Shimane, Japan); Kazuhide Matsushima (Division of Acute Care Surgery, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, United State); Toru Hifumi and Kasumi Shirasaki (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, St. Luke's International Hospital, Tokyo, Japan); Shigeyuki Furuta and Atsuko Fujikawa (Department of Pediatric Surgery and Department of Radiology, St. Marianna University School of Medicine Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan); Makoto Takaoka (Himeji Emergency Trauma and Critical Care Center, Steel Memorial Hirohata Hospital, Hyogo, Japan); Kaori Ito (Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Acute Care Surgery, Teikyo University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan); Satoshi Nara (Emergency and Critical Care Medical Center, Teine Keijinkai Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan); Shigeki Kushimoto and Atsushi Tanikawa (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Tohoku University Hospital, Miyagi, Japan); Masato Tsuchikane (Department of Emergency Medical and Critical Medicine, Tokai University Hachioji Hospital, Tokyo, Japan); Naoya Miura and Naoki Sakoda (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Tokai University Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan); Tadaaki Takada (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Tokushima Red Cross Hospital, Tokushima, Japan); Shogo Shirane (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Tokyo Bay Urayasu Ichikawa Medical Center, Chiba, Japan); Akira Endo and Keita Nakatsutsumi (Trauma and Acute Critical Care Center, Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan); Kenta Sugiura and Yusuke Hagiwara (Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Tokyo Metropolitan Children's Medical Center, Tokyo, Japan); and Tamotsu Gotou (Tajima Emergency & Critical Care Medical Center, Toyooka Hospital, Hyogo, Japan).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Osaka University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N. conceived the study. S.N., M.Y., and M.K. structured the methods and performed the data interpretation. S.N. prepared the manuscript. M.Y., M.K., H.O. and J.O. critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakao, S., Katsura, M., Yagi, M. et al. Assessing associated factors for failure of nonoperative management in pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries: a secondary analysis of the SHIPPs study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-024-02575-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-024-02575-y