Abstract

Purpose

The European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation funding program awarded the NIGHTINGALE grant to develop a toolkit to support first responders engaged in prehospital (PH) mass casualty incident (MCI) response. To reach the projects’ objectives, the NIGHTINGALE consortium used a Translational Science (TS) process. The present work is the first TS stage (T1) aimed to extract data relevant for the subsequent modified Delphi study (T2) statements.

Methods

The authors were divided into three work groups (WGs) MCI Triage, PH Life Support and Damage Control (PHLSDC), and PH Processes (PHP). Each WG conducted simultaneous literature searches following the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews. Relevant data were extracted from the included articles and indexed using pre-identified PH MCI response themes and subthemes.

Results

The initial search yielded 925 total references to be considered for title and abstract review (MCI Triage 311, PHLSDC 329, PHP 285), then 483 articles for full reference review (MCI Triage 111, PHLSDC 216, PHP 156), and finally 152 articles for the database extraction process (MCI Triage 27, PHLSDC 37, PHP 88). Most frequent subthemes and novel concepts have been identified as a basis for the elaboration of draft statements for the T2 modified Delphi study.

Conclusion

The three simultaneous scoping reviews allowed the extraction of relevant PH MCI subthemes and novel concepts that will enable the NIGHTINGALE consortium to create scientifically anchored statements in the T2 modified Delphi study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

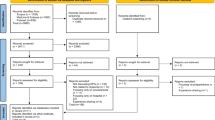

Sudden onset disasters (SODs) and mass casualty incidents (MCIs) from the past have made it evident that collaborative planning activities between public safety, public health, and clinical healthcare providers are essential for successful responses from the whole spectrum of prehospital (PH) response agencies, that must work together to forge and strengthen relationships to produce efficient and effective PH MCI responses [1,2,3]. As SODs and MCIs continue to increase, there is a real need to develop PH systems that are truly interoperable and integrated. Already in 2007, in response to the need for stronger connections and information exchange between response agencies, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created the Terrorism Injuries: Information, Dissemination, and Exchange (TIIDE) program [4, 5], ultimately aiming to decrease morbidity and mortality from MCIs, including those related to intentional acts of violence and terrorism. One of the projects awarded in the TIIDE was to work toward a national guideline for MCI response, gathering professionals that spanned over the continuum of care: emergency medical services, emergency medical specialists, and trauma surgeons. To achieve this objective, the TIIDE grant consortium partners used consensus methodology based on the best available science to propose the Sort, Assess, Life-Saving interventions, Treatment and/or Transport (SALT) national triage guideline[6] and a model uniform core criteria for mass casualty triage (MUCC) [7]. (Fig. 1).

Evolution of the structure and methodology adopted between the TIIDE and NIGHTINGALE project. ACEP American College of Emergency Physicians, ACS-COT American College of Surgeons-Committee on Trauma, AMA American Medical Association, ASL2 Azienda Sociosanitaria Ligure 2 (Italy), EMS Emergency Medical Services, ESTES European Society for Trauma and Emergency Surgery, MCI Mass Casualty Incidents, MDA Magen David Adom—Israel National Emergency Pre-Hospital Medical and Blood Services, MININT Ministry of Interior Italy, MRMID Swedish International Association for Promotion of Education and Training in Major Incidents and Disasters, MUCC Model Uniform Core Criteria for Mass Casualty Triage, NAEMT National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (US), NAEMSE National Association of Emergency Medical System Educators (US), NAEMSP National Association of Emergency Medical System Physicians (US), NASEMSO National Association of State Emergency Medical System Officials (US), SAMU Service d'Aide Médicale Urgente, Paris (France), SALT Sort, Assess, Life-Saving interventions, Treatment and/or Transport, UPO Università del Piemonte Orientale (Italy), USCS Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Italy)

Despite the literature emerging from the TIIDE project, that spurred further research, discussion, policy, and procedure, current emergency medical services and non-medical civil practitioners involved in PH MCI response often have to rely on complicated or even outdated procedures, multiple protocols or lack of homogeneity in response methods and guidelines, and technology of the past. [8,9,10,11]

To this end, the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations has been emphasizing the need to promote first responders’ preparedness through targeted actions that include the development and update of contingency plans, standard operating procedures, and multi-sector intervention, encouraging involvement of those affected by MCIs and disasters in the design and implementation of such preparedness actions. [12]

In 2020, the European Research Executive Agency (REA), in conjunction with the European Union (EU) Horizon 2020 research and innovation funding program, awarded the Novel InteGrated toolkit for enhanced pre-Hospital life support and Triage IN challenGing And Large Emergencies (NIGHTINGALE) grant to a consortium comprised of a similar wide distribution of PH MCI response agencies and research centers as TIIDE [13] (Fig. 1.). The NIGHTINGALE project features 11 objectives ranging from developing and implementing advanced devices and artificial intelligence, incorporating bystanders into the PH MCI response and addressing ethical challenges, enhancing the collaborative approach across different agencies (Supplementary Table 1). Having acknowledged the evidence produced by the TIIDE project [14], the NIGHTINGALE project seeks to strengthen the existing research in the field of PH MCI and to advance the depth and breadth of PH MCI response guidelines, as advocated by the REA. Therefore, the focus is to upgrade the evaluation of the injured, optimizing life support and damage control procedures and allow a shared response across different MCI responding agencies, including emergency medical services, non-medical civil protection personnel, volunteers, and citizens. To guide the creation of such evidence-based guidelines, the NIGHTINGALE consortium adopted the Translational Science (TS) consensus process that features progressive stages aiming to translate research-informed data into new knowledge in the form of recommendations and guidelines [15] (Fig. 1). As described by Caviglia et al., [16] starting from the TS question (T0), “how to develop, integrate, test, deploy, demonstrate and validate a Novel Integrated Toolkit for Emergency Medical Response which ensures an upgrade to PH MCI response?”, the application of TS in the NIGHTINGALE project entails the identification of current approaches and published data (T1, scoping literature review stage), the use of a consensus methodology as a basis for the development of evidence-based tools and guidelines (T2, modified Delphi), the translation into practice (T3, development of tools and guidelines), and a final evaluation stage (T4, evaluation and outcome assessment) (Fig. 1). In the T1 stage, three simultaneous scoping literature reviews were designed to identify sources and references on MCI Triage, PH Life Support and Damage Control (PHLSDC) interventions, and PH processes (PHP) that could then be interrogated using a defined data extraction tool to determine concepts, theories, and knowledge gaps. [15, 16] Hence, the aim of this work was to map, extract, and synthetize current evidence-based knowledge, gap, and challenges on MCI Triage, PHLSDC, and PHP through three different simultaneous scoping literature reviews, to inform the creation of an initial set of statements for the T2 modified Delphi study.

Methods

This study describes the structured T1 scoping literature reviews guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [17, 18]. To specifically address each component of the PH MCI response, the authors were divided into the three work groups (WGs) of MCI Triage, PHLSDC, and PHP. Each WG included health professionals and researchers with specific expertise in MCI response and patient management. Under the direction of a medical informaticist, the search strategy included only terms relating to or describing sudden onset disaster PH MCI response. The WGs conducted simultaneous searches from November 2021 to January 2022 following the same search term methodology until the search became more specific relating to each WG (MCI Triage, PHLSDC, and PHP), as shown in Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

The search included English-language papers published from January 1983 to October 2021 on PubMed, SCOPUS, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, EBSCO, Elton B. Stephens Company, Ipswich, Massachusetts USA), DTIC (Defense Technical Information Center, U.S. Department of Defense), CRI (Emergency Care Research Institute, Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, USA), and PsycInfo (American Psychological Association, Washington D.C., USA). The search terms were adapted for use with other bibliographic databases in combination with database-specific filters for controlled trials, where these were available. An ancestry search was also performed to identify additional references from the bibliography of references retrieved in the searches. The reference manager was EndNote™ X9 and 20 (Clarivate; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA). References that did not meet the inclusion criteria, specifically did not study or report an MCI or MCI exercise, were excluded.

Search strategy

After each WG conducted its initial search, duplicates were removed. Reviewers in each WG independently screened reference titles and abstracts to determine if inclusion criteria were met. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion within the WG. Each WG removed any reference that did not meet inclusion criteria from further consideration. Subsequently, full texts of included articles were screened, disagreement was resolved by discussion, and references that did not meet inclusion criteria were removed. The remaining included articles for each WG underwent data extraction into an Excel database (Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, Washington, USA) that was developed using themes and subthemes from PH MCI response literature and in compliance with the NIGHTINGALE objectives. This raw data, together with other information gleaned from the full reference review process (such as relevant tables, figures, or writings) constituted the base for the development of the initial set of statements in the T2 modified Delphi stage. Specifically, the data extraction process focused on extracting data that could lead to the creation of relevant statements for the T2 stage by identifying recurrent subjects and innovative concepts that have the potential to improve current practices in PH MCI management but for which validation in clinical settings is still underway.

Results

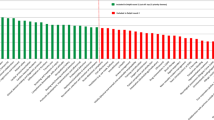

The initial search for all 3 WGs yielded 925 references. Following title and abstract review, 483 articles were considered for full text review. Finally, 152 articles were included in the database extraction process: MCI Triage [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], PHLSDC [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81], PHP [30, 43, 82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167]. (Table 2).

Different thematic categories and related subthemes were created by each WG (Table 3). The data extraction process drew attention to subthemes frequently mentioned in the included references. Specifically, recurrent subthemes in the MCI Triage WG were the recording of mechanism of injury (n = 21), the involvement of bystanders (n = 8), the use of basic monitoring in support of PH triage procedures (including cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry, respectively, mentioned n = 12 and n = 10 times), re-assessment of MCI casualties though continuous vital signs monitoring (n = 14), treatment prioritization (n = 15), and evacuation prioritization (n = 19) as the main outcomes of the MCI Triage process. Additionally, references included in the MCI Triage data extraction drew attention to the concepts of shock index, pulse pressure, and heart rate variability to be used in the PH assessment of casualties [23, 35].

Among the 37 references included in the PHLSDC data extraction, the subthemes more frequently identified were the collection of the mechanism of injury (n = 13) and exposure to environment time (n = 12), the importance of stopping the bleeding maneuvers (n = 11) and PH fluid resuscitation (n = 14), basic and advanced monitoring to guide PHLSDC interventions, including cardiac monitoring (n = 9), pulse oximetry (n = 6), and physiological monitoring (n = 7), re-assessment of MCI casualties through continuous vital signs monitoring (n = 8) and treatment of casualties according to triage prioritization (n = 13). Furthermore, the authors identified the following “hot” issues worthy of further attention: PH management of crush syndrome [75], resuscitation of avalanche victims [53, 54], and shared CBRNE treatment protocols [60, 81].

Lastly, the subthemes commonly identified in the PHP data extraction included aspects pertaining to MCI PHP terminology, policy and planning framework, and incident activation/notification. Aspects related to decontamination (n = 10) and hazard assessment (n = 15) were also frequently mentioned. Furthermore, subthemes related to casualty distribution (either through coordinated/planned methodologies n = 19 or an ad hoc distribution model n = 19), communication and situational awareness (including the use of social media, radio communication and drones), resource allocation and the integration of technology to support PHP were identified.

Discussion

The three simultaneous PRISMA scoping reviews were performed in the T1 stage of a TS process, ultimately seeking to advance MCI PH response guidelines in the framework of the EU-funded NIGHTINGALE project. This initial step of mapping current available evidence through the analysis of recurrent subthemes, common practices, and new concepts identified in MCI Triage, PHLSDC, and PHP literature will serve as the basis for the development of three initial sets of statements during the T2 modified Delphi stage. Indeed, results of the three scoping reviews emphasized several aspects that have been recurrently investigated in the MCI literature and for which expert consensus was deemed as needed by the authors.

Despite MCI Triage being the mainstay of initial casualty management, no global consensus or gold standard definition exists across different countries, and most PH practitioners have received training in the initial MCI Triage system favored by their specific agency and jurisdiction [6]. Since numerous attempts have been made toward developing shared guidelines for MCI Triage [5] or in the attempt to create a universal triage tool [168], the NIGHTINGALE project recognizes the necessity to study these efforts as a progression of the previous above mentioned projects. Results of the MCI Triage scoping review determined that recording the mechanism of injury from the initial assessment and as more details emerge over the continuum of care is important for the definitive treatment team [19, 21, 23,24,25,26, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, 39, 41,42,43,44,45]. This includes obtaining information not only from EMS staff but also non-medical bystanders who rendered first aid or assisted EMS [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], reinforcing the concept that gathering relevant observations from bystanders could support the MCI response efforts, in compliance with the NIGHTINGALE objectives. Information supporting the continuum of care involving the initial and subsequent assessments of vital signs should determine treatment and evacuation prioritization, considering the use of cardiac monitors and pulse oximetry when available. While literature suggests the use of advanced physiologic monitoring and the incorporation of point-of-care ultrasound in the continuum of care [21, 31], it is also evident that initial assessment of MCI casualties should remain quick, practical, easy to remember by all first responders and applicable across different environments including austere settings, thus, to be performed without diagnostic equipment. Appropriate tagging and tracing of MCI casualties remains a pillar of any MCI Triage system adopted, opening the door for innovative solutions and tools possibly fulfilling the triple function of tagging, tracing, and continuous monitoring [27, 42, 44].

References from the PHLSDC scoping review highlighted the need to focus on assessment and treatment guidelines for crush injuries during MCIs [46, 63, 75], as well as for the development of awareness on chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive (CRBNE) events, advocating for education, training, and competencies to be developed across all agencies [48, 57, 71, 76, 79, 81]. Similarly, control of major hemorrhages as an integral part of the triage process emerged as a recurrent topic in the included PHLSDC references, with a special emphasis on the role of non-medical bystanders, as specifically stressed by the Hartford Consensus after the Sandy Hook Elementary School mass shooting and by Lesaffre and colleagues after the 2015 Paris attacks [46,47,48, 50, 51, 61,62,63, 73, 77, 80, 169]. Overall, attention was given to the importance of continuous real-time monitoring and re-assessment of casualties to guide prioritization of life-saving interventions and transportation, suggesting the possibility to introduce deployable technology, provided it to be quick, reliable, and easy to use [48, 50, 54,55,56, 63, 69, 75, 76].

Results of the PHP scoping review stressed the importance of a common terminology to be adopted across all agencies working in the same jurisdiction, along with the urgent need to include practices that support gender diversity and are contextual to vulnerable groups and special needs populations [30, 111, 140, 147, 159, 160]. Included references addressed the role of technology in supporting the different PH MCI processes, from inter-agencies communication systems, to telemedicine and information management systems to coordinate the different resources deployed (including human resources, equipment, and vehicles) and to distribute MCI casualties in different health facilities [90, 92, 99, 146, 160]. Data supported that standard trauma transportation decisions and overall MCI coordination may have to be adapted in context to the hazard impact and health system capacity, taking into account the possibility of CBRNE threats demanding from patient decontamination and personnel self-care [86, 88, 89, 100, 102, 103, 108, 136]. Additionally, from the results emerged that frequently definitive care may require alternative care sites to include field hospitals, adapted structures such as conventions centers, schools, or religious buildings like churches and mosques that have the capacity and capability to attend the injured [105, 131, 151]. The concept of enhancing situational awareness through available technology (such as drones) to better guide critical decision-making during MCIs emerged in some of the included references, especially in remote areas with access constraints [90, 92, 99, 109, 117, 129, 133, 139, 146, 160]. Moreover, the role of spontaneous volunteers and bystanders both in assisting relief efforts [88, 107, 133, 134, 141, 144, 166] and in providing information through social media that could be used for rapid situation assessment [129] consistently emerges in the included references. Lastly, a recurrent notion highlighted in the included references was the need for a structured MCI plan able to regulate the use of technical advances, to foster education and training competences across different agencies, to allow for structured debriefing in a collaborative manner, and to promote the use of key performance indicators to evaluate and improve the response [83,84,85,86, 91, 98, 100,101,102,103,104, 107, 109,110,111,112, 116, 119, 120, 122, 124, 131, 135, 137, 142, 145, 148, 153, 158, 160, 164, 166].

Limitations

A scoping review intends to capture all included peer-reviewed publications as well as the ancestry publications that were cited in these publications. The Grey literature presents challenges to obtain relevant references and all attempts were made to include these references, but some may not have been obtained. There is no way to know if these potential missing references would have made a difference in the available information to extract data. The raw data extracted by WG members and the work group lead are intended to undergo further analysis within each work group to create the initial T2 modified Delphi statements. This data extraction process, though intended to be encompassing and comprehensive, may not have captured relevant data due to the thematic approach of the database. There is no way to know if relevant data were not extracted but the secondary data retained by each work group member as they read each full reference article provide additional information for the statement creation process.

Conclusion

The progression of the science to critically examine the PH MCI response peer-reviewed medical literature and other sources has enabled the NIGHTINGALE partners to methodically obtain raw data and secure relevant tables, figures, or writings that will contribute to each WG’s creation of the initial T2 modified Delphi study statements. Once submitted to experts, statements that achieve consensus will be used to define guidelines and recommendation, in compliance with the objectives of the NIGHTINGALE project.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Heide E. Disaster response: principles of preparation & coordination. Publ Prod Manag Rev. 1989;1:15. https://doi.org/10.2307/3380618.

Kapucu N. Interorganizational coordination in complex environments of disasters: the evolution of intergovernmental disaster response systems. J Homeland Secur Emergency Manag [Internet]. 2009 Jul 10 [cited 2022 Nov 16];6(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1498

Mills AF, Helm JE, Jola-Sanchez AF, Tatikonda MV, Courtney BA. Coordination of autonomous healthcare entities: emergency response to multiple casualty incidents. Prod Oper Manag. 2018;27(1):184–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12790.

Injury Center Funding Opportunity Announcements (FOAs). United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Injury Response, created the Terrorism Injuries: Information, Dissemination and Exchange (TIIDE) project. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2022 Nov 11].

Hunt R. TIIDE Project 2009 Annual Report Terrorism Injuries: Information, Dissemination and Exchange. Supplemental Material.

Lerner EB, Schwartz RB, Coule PL, Weinstein ES, Cone DC, Hunt RC, et al. Mass casualty triage: an evaluation of the data and development of a proposed national guideline. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(Suppl 1):S25-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/DMP.0b013e318182194e.

Lerner EB, Cone DC, Weinstein ES, Schwartz RB, Coule PL, Cronin M, et al. Mass casualty triage: an evaluation of the science and refinement of a national guideline. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5(2):129–37. https://doi.org/10.1001/dmp.2011.39.

Federal Interagency Committee on EMS. National Implementation of the Model Uniform Core Criteria for Mass Casualty Incident Triage [Internet]. 2014 Mar [cited 2022 Nov 15].

American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Surgeons—Committee on Trauma, American Trauma Society, Children’s National Medical Center, Child Health Advocacy Institute, Emergency Medical Services for Children National Resource Center, International Association of Emergency Medical Services Chiefs, et al. Model uniform core criteria for mass casualty triage. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011 Jun;5(2):125–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/dmp.2011.41

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Model Uniform Core Criteria for Mass Casualty Incident Triage: Addendum to the Paramedic Instructional Guidelines [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2022 Nov 5].

Holgersson A. Review of On-Scene Management of Mass-Casualty Attacks. Journal of Human Security. 2016 Aug 29;12. https://doi.org/10.12924/johs2016.12010091

European Commission. DG ECHO Guidance Note - Disaster Preparedness. 01012021. :84.

Novel InteGrated toolkit for enhanced pre-Hospital life support and Triage IN challenGing And Large Emergencies [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 14].

EMSFocus. Teaching Mass Casualty Triage: Implementing the New MUCC Instructional Guidelines. [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 24].

Weinstein ES, Cuthbertson JL, Ragazzoni L, Verde M. A T2 translational science modified delphi study: spinal motion restriction in a resource-scarce environment. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2020;35(5):538–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X20000862.

Caviglia M, Cuthbertson J, Sdongos E, Faccincani R, Ragazzoni L, Weinstein ES. Translational Science in Disaster Medicine: from grant to deliverables. Int J Disaster Risk Reduction. 2022 Jul 1;

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Cancio LC, Wade CE, West SA, Holcomb JB. Prediction of mortality and of the need for massive transfusion in casualties arriving at combat support hospitals in Iraq. J Trauma. 2008 Feb;64(2 Suppl):S51–55; discussion S55–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181608c21

Coimbra R, Lee J, Bansal V, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P. Recognizing/accepting futility: prehospital, emergency center, operating room, and intensive care unit. J Trauma Nurs. 2007 Jun;14(2):73–6; quiz 77–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JTN.0000278791.43783.df

Convertino VA, Cooke WH, Salinas J, Holcomb JB. Advanced Capabilities for Combat Medics. [cited 2022 Nov 14];

Arcos González P, Castro Delgado R, Cuartas Alvarez T, Garijo Gonzalo G, Martinez Monzon C, Pelaez Corres N, et al. The development and features of the Spanish prehospital advanced triage method (META) for mass casualty incidents. Scandinavian J Trauma Resuscitation Emergency Med. 2016;24(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-016-0255-y.

Cooke WH, Salinas J, Convertino VA, Ludwig DA, Hinds D, Duke JH, et al. Heart rate variability and its association with mortality in prehospital trauma patients. J Trauma. 2006 Feb;60(2):363–70; discussion 370. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000196623.48952.0e

Di Carlo S, Cavallaro G, Palomeque K, Cardi M, Sica G, Rossi P, et al. Prehospital hemorrhage assessment criteria: a concise review. J Trauma Nurs. 2021;28(5):332–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTN.0000000000000608.

Duke JH, Holcomb JB. Noninvasive Continuous Physiologic Data Acquisition and Analysis as a Predictor of Outcome Following Major Trauma: A Pilot Study [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 14].

Eastridge BJ, Butler F, Wade CE, Holcomb JB, Salinas J, Champion HR, et al. Field triage score (FTS) in battlefield casualties: validation of a novel triage technique in a combat environment. Am J Surg. 2010;200(6):724–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.08.006.

Elmasllari E, Reiners R. Learning From Non-Acceptance: Design Dimensions for User Acceptance of E-Triage Systems. In: 14th Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, Albi, France, May 21–24, 2017 [Internet]. ISCRAM Association; 2017 [cited 2022 Nov 14].

Jetten WD, Seesink J, Klimek M. Prehospital triage by lay person first responders: a scoping review and proposal for a new prehospital triage tool. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021;8:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.19.

Lockey DJ, Mackenzie R, Redhead J, Wise D, Harris T, Weaver A, et al. London bombings July 2005: the immediate pre-hospital medical response. Resuscitation. 2005;66(2):ix–xii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.07.005.

Lyle K, Thompson T, Graham J. Pediatric mass casualty: triage and planning for the prehospital provider. Clin Pediatric Emergency Med. 2009;10(3):173–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpem.2009.06.004.

Maddry J, Savell S, Baldwin DS. Austere, Pre-Transport, Qualitative Clinical Testing. [cited 2022 Nov 14];

Martín-Rodríguez F, López-Izquierdo R, Del Pozo VC, Delgado Benito JF, Carbajosa Rodríguez V, Diego Rasilla MN, et al. Accuracy of national early warning score 2 (NEWS2) in prehospital triage on in-hospital early mortality: a multi-center observational prospective cohort study. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34(6):610–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X19005041.

Newgard CD, Richardson D, Holmes JF, Rea TD, Hsia RY, Mann NC, et al. Physiologic field triage criteria for identifying seriously injured older adults. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(4):461–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/10903127.2014.912707.

Newgard CD, Rudser K, Hedges JR, Kerby JD, Stiell IG, Davis DP, et al. A critical assessment of the out-of-hospital trauma triage guidelines for physiologic abnormality. J Trauma. 2010;68(2):452–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ae20c9.

Newgard CD, Cheney TP, Chou R, Fu R, Daya MR, O’Neil ME, et al. Out-of-hospital circulatory measures to identify patients with serious injury: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(12):1323–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14056.

Parker B. Neural network medical decision algorithms for pre-hospital trauma care [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 29].

Reifman J, Chen L, Khitrov MY, Reisner AT. Automated Decision-Support Technologies for Prehospital Care of Trauma Casualties [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 14].

Reisner A, Chen X, Kumar K, Reifman J. Prehospital heart rate and blood pressure increase the positive predictive value of the glasgow coma scale for high-mortality traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(10):906–13. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2013.3128.

Rickards CA, Ryan KL, Cooke WH, Romero SA, Convertino VA. Combat stress or hemorrhage? Evidence for a decision-assist algorithm for remote triage. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2008;79(7):670–6. https://doi.org/10.3357/asem.2223.2008.

Rodriguez D, Heuer S, Guerra A, Stork W, Weber B, Eichler M. Towards automatic sensor-based triage for individual remote monitoring during mass casualty incidents. In: 2014 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). 2014. p. 544–51. https://doi.org/10.1109/BIBM.2014.6999217

Romero Pareja R, Castro Delgado R, Turégano Fuentes F, Jhon Thissard-Vasallo I, Sanz Rosa D, Arcos GP. Prehospital triage for mass casualty incidents using the META method for early surgical assessment: retrospective validation of a hospital trauma registry. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46(2):425–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-1040-6.

Ryan K, George D, Liu J, Mitchell P, Nelson K, Kue R. The use of field triage in disaster and mass casualty incidents: a survey of current practices by EMS personnel. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(4):520–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1419323.

Turner CDA, Lockey DJ, Rehn M. Pre-hospital management of mass casualty civilian shootings: a systematic literature review. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1543-7.

Zhao X, Rafiq A, Hummel R, Fei D-Y, Merrell RC. Integration of information technology, wireless networks, and personal digital assistants for triage and casualty. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12(4):466–74. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2006.12.466.

Lin C-H, Lin C-H, Tai C-Y, Lin Y-Y, Shih FF-Y. Challenges of burn mass casualty incidents in the prehospital setting: lessons from the formosa fun coast park color party. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2019 Jan 2;23(1):44–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2018.1479473

Ashkenazi I, Isakovich B, Kluger Y, Alfici R, Kessel B, Better OS. Prehospital management of earthquake casualties buried under rubble. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2005;20(2):122–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00002302.

Bachman MW, Anzalone BC, Williams JG, DeLuca MB, Garner DG, Preddy JE, et al. Evaluation of an integrated rescue task force model for active threat response. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(3):309–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2018.1521487.

Baker DJ. Management of respiratory failure in toxic disasters. Resuscitation. 1999;42(2):125–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9572(99)00098-2.

Bartkus EA, Daya M, Hedges JR, Jui J. ExacTech blood glucose meter clinical trial. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1993;8(3):217–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00040395.

Blackbourne LH, Baer DG, Eastridge BJ, Kheirabadi B, Bagley S, Kragh JF, et al. Military medical revolution: prehospital combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S372-377. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3182755662.

Bobko JP, Lai TT, Smith R, Shapiro G, Baldridge T, Callaway DW. Tactical emergency casualty care?pediatric appendix: novel guidelines for the care of the pediatric casualty in the high-threat, prehospital environment. J Spec Oper Med. 2013;13(4):94–107. https://doi.org/10.55460/EF77-LDYW

Ct B, Wg D. Organizing the orthopaedic trauma association mass casualty response team. Clinical orthopaedics and related research [Internet]. 2004 May [cited 2022 Nov 14];(422). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000131200.12795.2b

Boué Y, Payen J-F, Brun J, Thomas S, Levrat A, Blancher M, et al. Survival after avalanche-induced cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85(9):1192–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.015.

Brugger H, Paal P, Boyd J. Prehospital resuscitation of the buried avalanche victim. High Alt Med Biol. 2011;12(3):199–205. https://doi.org/10.1089/ham.2011.1025.

Cardoso MM, Banner MJ, Melker RJ, Bjoraker DG. Portable devices used to detect endotracheal intubation during emergency situations: a review. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(5):957–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-199805000-00036.

Carley S, Mackway-Jones K, Randic L, Dunn K. Planning for major burns incidents by implementing an accelerated Delphi technique. Burns. 2002;28(5):413–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-4179(02)00107-9.

Carli P, Telion C, Baker D. Terrorism in France. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2003;18(2):92–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00000820.

Corcoran F, Bystrzycki A, Masud S, Mazur SM, Wise D, Harris T. Ultrasound in pre-hospital trauma care. Trauma. 2016;18(2):101–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460408615606753.

Davis BL, Martin MJ, Schreiber M. Military resuscitation: lessons from recent battlefield experience. Curr Trauma Rep. 2017;3(2):156–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-017-0088-9.

de Schoutheete J-C, Hachimi Idrissi S, Watelet J-B. Pre-hospital interventions: introduction to life support systems. B-ENT. 2016;Suppl 26(1):41–54. PMID:29461733

Dudaryk R, Pretto EA. Resuscitation in a multiple casualty event. Anesthesiol Clin. 2013;31(1):85–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2012.11.002.

Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, Cantrell J, Tops T, Uribe P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001–2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S431-437. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3182755dcc.

Eilertsen KA, Winberg M, Jeppesen E, Hval G, Wisborg T. Prehospital tourniquets in civilians: a systematic review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021;36(1):86–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X20001284.

Fattah S, Rehn M, Reierth E, Wisborg T. Systematic literature review of templates for reporting prehospital major incident medical management. BMJ Open. 2013 Aug 1;3(8):e002658. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002658

Fuse A, Okumura T, Tokuno S, Saitoh D, Yokota H. Current Status of Preparedness for Blast Injuries in Japan. 2011;54(5):8

Hardwick JM, Murnan SD, Morrison-Ponce DP, Devlin JJ. Field expedient vasopressors during aeromedical evacuation: a case series from the puerto rico disaster response. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2018;33(6):668–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X18000973.

Horrocks P, Hobbs L, Tippett V, Aitken P. Paramedic disaster health management competencies: a scoping review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34(3):322–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X19004357.

Jacobs LM, Wade DS, McSwain NE, Butler FK, Fabbri WP, Eastman AL, et al. The hartford consensus: THREAT, a medical disaster preparedness concept. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(5):947–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.002.

Kornhall DK, Martens-Nielsen J. The prehospital management of avalanche victims. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162(6):406–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2015-000441.

Lal D, Weiland S, Newton M, Flaten A, Schurr M. Prehospital hyperventilation after brain injury: a prospective analysis of prehospital and early hospital hyperventilation of the brain-injured patient. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2003;18(1):20–3. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00000637.

Laurent JF, Richter F, Michel A. Management of victims of urban chemical attack: the French approach. Resuscitation. 1999;42(2):141–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-9572(99)00099-4.

Leclerc T, Potokar T, Hughes A, Norton I, Alexandru C, Haik J, et al. A simplified fluid resuscitation formula for burns in mass casualty scenarios: analysis of the consensus recommendation from the WHO emergency medical teams technical working group on burns. Burns. 2021;47(8):1730–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2021.02.022.

Loftus A, Pynn H, Parker P. Improvised first aid techniques for terrorist attacks. Emerg Med J. 2018;35(8):516–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2018-207480.

Mansky R, Scher C. Thoracic trauma in military settings: a review of current practices and recommendations. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019;32(2):227–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000694.

Mardones A, Arellano P, Rojas C, Gutierrez R, Oliver N, Borgna V. Prevention of crush syndrome through aggressive early resuscitation: clinical case in a buried Worker. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(3):340–2. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X16000327.

O’Brien DJ, Walsh DW, Terriff CM, Hall AH. Empiric management of cyanide toxicity associated with smoke inhalation. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(5):374–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X11006625.

Pons PT, Jerome J, McMullen J, Manson J, Robinson J, Chapleau W. The hartford consensus on active shooters: implementing the continuum of prehospital trauma response. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(6):878–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.09.013.

Randic L, Carley S, Mackway-Jones K, Dunn K. Planning for major burns incidents in the UK using an accelerated Delphi technique. Burns. 2002;28(5):405–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-4179(02)00108-0.

Riccobono D, Valente M, Drouet M, Calamai F, Abriat A. French policies for victim management during mass radiological accidents/attacks. Health Phys. 2018;115(1):179–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000000839.

Soffer D, Klausner JM. Trauma system configurations in other countries: the Israeli model. Surg Clin North Am. 2012 Aug;92(4):1025–40, x. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2012.04.007

Tokuda Y, Kikuchi M, Takahashi O, Stein GH. Prehospital management of sarin nerve gas terrorism in urban settings: 10 years of progress after the Tokyo subway sarin attack. Resuscitation. 2006;68(2):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.05.023.

CDC 2017 Hurricane Incident Management System Team. Hurricane Season Public Health Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Guidance for Health Care Providers, Response and Recovery Workers, and Affected Communities - CDC, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Sep 22;66(37):995–8. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6637e1

Adini B, Bodas M, Nilsson H, Peleg K. Policies for managing emergency medical services in mass casualty incidents. Injury. 2017;48(9):1878–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.05.034.

Adini B, Cohen R, Glassberg E, Azaria B, Simon D, Stein M, et al. Reconsidering policy of casualty evacuation in a remote mass-casualty incident. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2014;29(1):91–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X13008935.

Adini B, Peleg K. On constant alert: lessons to be learned from Israel’s emergency response to mass-casualty terrorism incidents. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2179–85. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0956.

Agiv-Berland A, Ashkenazi I, Aharonson-Daniel L. The Cross-National Adaptability of EMS Protocols for Mass Casualty Incidents. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management [Internet]. 2012 Oct 31 [cited 2022 Nov 14];9(2). https://doi.org/10.1515/1547-7355.2036

Al Thobaity A, Plummer V, Williams B. What are the most common domains of the core competencies of disaster nursing? A scoping review Int Emerg Nurs. 2017;31:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2016.10.003.

Amat Camacho N, Karki K, Subedi S, von Schreeb J. International Emergency Medical Teams in the Aftermath of the 2015 Nepal Earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34(3):260–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X19004291.

Amlôt R, Carter H, Riddle L, Larner J, Chilcott RP. Volunteer trials of a novel improvised dry decontamination protocol for use during mass casualty incidents as part of the UK’S Initial Operational Response (IOR). PLOS ONE. 2017 Jun 16;12(6):e0179309. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179309

Amlot R, Larner J, Matar H, Jones DR, Carter H, Turner EA, et al. Comparative analysis of showering protocols for mass-casualty decontamination. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2010;25(5):435–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00008529.

Amram O, Schuurman N, Hedley N, Hameed SM. A web-based model to support patient-to-hospital allocation in mass casualty incidents. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(5):1323–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318246e879.

Anan H, Otomo Y, Homma M, Oshiro K, Kondo H, Shimamura F, et al. Proposal for reforming prehospital response to chemical terrorism disasters in Japan: going back to the basics of saving the lives of the injured by securing the safety of the rescue team. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2020;35(1):88–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X19005119.

Arnold JL, Levine BN, Manmatha R, Lee F, Shenoy P, Tsai M-C, et al. Information-sharing in out-of-hospital disaster response: the future role of information technology. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19(3):201–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00001783.

Assa A, Landau D-A, Barenboim E, Goldstein L. Role of air-medical evacuation in mass-casualty incidents–a train collision experience. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(3):271–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00006920.

Aylwin CJ, König TC, Brennan NW, Shirley PJ, Davies G, Walsh MS, et al. Reduction in critical mortality in urban mass casualty incidents: analysis of triage, surge, and resource use after the London bombings on July 7, 2005. Lancet. 2006;368(9554):2219–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69896-6.

Bloch YH, Schwartz D, Pinkert M, Blumenfeld A, Avinoam S, Hevion G, et al. Distribution of casualties in a mass-casualty incident with three local hospitals in the periphery of a densely populated area: lessons learned from the medical management of a terrorist attack. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2007;22(3):186–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00004635.

Campion EM, Juillard C, Knudson MM, Dicker R, Cohen MJ, Mackersie R, et al. Reconsidering the resources needed for multiple casualty events: lessons learned from the crash of asiana airlines flight 214. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):512–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5107.

Carter H, Drury J, Rubin GJ, Williams R, Amlôt R. Public experiences of mass casualty decontamination. Biosecur Bioterror. 2012;10(3):280–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2012.0013.

Castro Delgado R, Naves Gómez C, Cuartas Álvarez T, Arcos GP. An epidemiological approach to mass casualty incidents in the Principality of Asturias (Spain). Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24(24):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-016-0211-x.

Chan TC, Griswold WG, Buono C, Kirsh D, Lyon J, Killeen JP, et al. Impact of wireless electronic medical record system on the quality of patient documentation by emergency field responders during a disaster mass-casualty exercise. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(4):268–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X11006480.

Chilcott RP, Mitchell H, Matar H. Optimization of nonambulant mass casualty decontamination protocols as part of an initial or specialist operational response to chemical incidents. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(1):32–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2018.1469705.

Chokshi NK, Behar S, Nager AL, Dorey F, Upperman JS. Disaster management among pediatric surgeons: preparedness, training and involvement. Am J Disaster Med. 2008;3(1):5–14 (PMID:18450274).

Collins S, James T, Carter H, Symons C, Southworth F, Foxall K, et al. Mass casualty decontamination for chemical incidents: research outcomes and future priorities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063079.

Cordner S, Ellingham STD. Two halves make a whole: Both first responders and experts are needed for the management and identification of the dead in large disasters. Forensic Sci Int. 2017;279:60–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.07.020.

Cotter S. Treatment area considerations for mass casualty incidents. Emerg Med Serv. 2006;35(2):48–51 (PMID:16541952).

Cowley RA, Gretes AJ. EMS Response to Mass Casualties. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1984;2(3):687–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-8627(20)30882-8.

Curnin S. Large civilian air medical jets: implications for Australian disaster health. Air Med J. 2012;31(6):284–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2012.04.001.

Daddoust L, Asgary A, McBey KJ, Elliott S, Normand A. Spontaneous volunteer coordination during disasters and emergencies: Opportunities, challenges, and risks. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2021 Nov 1;65:102546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102546

Dart R, Bevelaqua A, DeAtley C, Sidell F, Goldfrank L, Madsen J, et al. Countering Chemical Agents: Multi-specialty panel presents consensus guidelines for prehospital management of mass casualties from chemical warfare agents. Jems: Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 2006 Dec 1;31:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-2510(06)70586-1

Daud L, Utaberta N, Ismail N, Yazid M, Mohd YUNOS MY, Mohd Ariffin N, et al. Mitigating flood disaster in Kelantan : Effectiveness of emergency response by volunteers. Advances in Environmental Biology. 2015 Jan 1;9:61–4.

Desmond M, Schwengel D, Chilson K, Rusy D, Ingram K, Ambardekar A, et al. Paediatric patients in mass casualty incidents: a comprehensive review and call to action. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128(2):e109–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.10.026.

Doyle CJ. Mass casualty incident. Integration with prehospital care. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1990 Feb;8(1):163–75. PMID:2403920

Egan JR, Amlôt R. Modelling mass casualty decontamination systems informed by field exercise data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(10):3685–710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9103685.

Epstein RH, Ekbatani A, Kaplan J, Shechter R, Grunwald Z. Development of a staff recall system for mass casualty incidents using cell phone text messaging. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(3):871–8. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cb3f9e.

Fenn J, Rega P, Stavros M, Buderer NF. Assessment of U.S. helicopter emergency medical services’ planning and preparedness for disaster response. Air Med J. 1999 Mar;18(1):12–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1067-991x(99)90003-2

Garner A, Nocera A. Should New South Wales hospital disaster teams be sent to major incident sites? Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69(10):702–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01672.x.

Griffiths JL, Kirby NR, Waterson JA. Three years experience with forward-site mass casualty triage-, evacuation-, operating room-, ICU-, and radiography-enabled disaster vehicles: development of usage strategies from drills and deployments. Am J Disaster Med. 2014;9(4):273–85. https://doi.org/10.5055/ajdm.2014.0179.

Gulesan OB, Anil E, Boluk PS. Social media-based emergency management to detect earthquakes and organize civilian volunteers. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2021 Nov 1;65:102543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102543

Hale JF. Managing a disaster scene and multiple casualties before help arrives. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008 Mar;20(1):91–102, vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2007.10.012

Hall TN, McDonald A, Peleg K. Identifying factors that may influence decision-making related to the distribution of patients during a mass casualty incident. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2018;12(1):101–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2017.43.

Han R, Wang W, Shi J. Motivation of sichuan earthquake volunteers and its implication for emergency management. Proceedings—4th International Joint Conference on Computational Sciences and Optimization, CSO 2011. 2011. 658 p. https://doi.org/10.1109/CSO.2011.168

Hunt P. Lessons identified from the 2017 Manchester and London terrorism incidents. Part 1: introduction and the prehospital phase. BMJ Mil Health. 2020 Apr;166(2):111–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2018-000934

Hyder S, Manzoor AF, Iqbal MA. Policy Implementation: Teachers’ Role as First Responders in Emergencies and Disasters. Kesmas: Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat Nasional (National Public Health Journal) [Internet]. 2020 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Nov 14];15(4). https://doi.org/10.21109/kesmas.v15i4.2989

Ishikawa K, Jitsuiki K, Ohsaka H, Yoshizawa T, Obinata M, Omori K, et al. Management of a mass casualty event caused by electrocution using doctor helicopters. Air Med J. 2016;35(3):180–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2015.12.012.

Kaplowitz L, Reece M, Hershey JH, Gilbert CM, Subbarao I. Regional health system response to the Virginia Tech mass casualty incident. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1(1 Suppl):S9-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/DMP.0b013e318149f5a2.

Kearns RD, Holmes JH, Skarote MB, Cairns CB, Strickland SC, Smith HG, et al. Disasters; the 2010 Haitian earthquake and the evacuation of burn victims to US burn centers. Burns. 2014;40(6):1121–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2013.12.015.

Kearns R, Hubble M, Holmes J, Cairns B. Disaster planning: transportation resources and considerations for managing a burn disaster. J Burn Care Res. 2013;28:35. https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182853cf7.

Khajehaminian MR, Ardalan A, Hosseini Boroujeni SM, Nejati A, Keshtkar A, Foroushani AR, et al. Criteria and models for the distribution of casualties in trauma-related mass casualty incidents: a systematic literature review protocol. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0538-z.

Khajehaminian MR, Ardalan A, Keshtkar A, Hosseini Boroujeni SM, Nejati A, Ebadati EOME, et al. A systematic literature review of criteria and models for casualty distribution in trauma related mass casualty incidents. Injury. 2018;49(11):1959–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.09.005.

Kryvasheyeu Y, Chen H, Obradovich N, Moro E, Van Hentenryck P, Fowler J, et al. Rapid assessment of disaster damage using social media activity. Science Advances. 2016 Mar 11;2(3):e1500779. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500779

Lavon O, Hershko D, Barenboim E. Large-scale air-medical transport from a peripheral hospital to level-1 trauma centers after remote mass-casualty incidents in Israel. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(6):549–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00007500.

Lee W-H, Chiu T-F, Ng C-J, Chen J-C. Emergency medical preparedness and response to a Singapore airliner crash. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(3):194–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb00243.x.

Levy MJ. Intentional Mass Casualty Events: Implications for Prehospital Emergency Medical Services Systems. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15(4):157–9. https://doi.org/10.55460/K4BK-WQNR

Ludwig T, Kotthaus C, Reuter C, van Dongen S, Pipek V. Situated crowdsourcing during disasters: managing the tasks of spontaneous volunteers through public displays. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2017;1(102):103–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.09.008.

Martínez P, Jaime D, Contreras D, Moreno M, Bonacic C, Marín M. Design and validation of an instrument for selecting spontaneous volunteers during emergencies in natural disasters. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2021 Jun 1;59:102243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102243

McCunn M, Ashburn MA, Floyd TF, Schwab CW, Harrington P, Hanson CW, et al. An organized, comprehensive, and security-enabled strategic response to the Haiti earthquake: a description of pre-deployment readiness preparation and preliminary experience from an academic anesthesiology department with no preexisting international disaster response program. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(6):1438–44. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181f42fd3.

Monteith RG, Pearce LDR. Self-care decontamination within a chemical exposure mass-casualty incident. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2015;30(3):288–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X15004677.

Morris G. Common errors in mass casualty management. Corrective actions for the prehospital provider. JEMS. 1986 Feb;11(2):34–8. PMID:10275920

Mundorff AZ, Bartelink EJ, Mar-Cash E. DNA preservation in skeletal elements from the world trade center disaster: recommendations for mass fatality management. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(4):739–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01045.x.

Nagata T, Rosborough SN, Rosborogh SN, VanRooyen MJ, Kozawa S, Ukai T, et al. Express railway disaster in Amagasaki: a review of urban disaster response capacity in Japan. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006;21(5):345–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x0000399x.

O’Neill PA. The ABC’s of disaster response. Scand J Surg. 2005;94(4):259–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/145749690509400403.

Ocak T, Duran A, Ozdes T, Hocagil C, Kucukbayrak A. Problems encountered by volunteers assisting the relief efforts in van, turkey and the surrounding earthquake area. J Acad Emergency Med. 2013;24(12):66–70. https://doi.org/10.5152/jaem.2013.029.

Olchin L, Krutz A. Nurses as first responders in a mass casualty: are you prepared? J Trauma Nurs. 2012;19(2):122–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTN.0b013e3182562984.

Orr SM, Robinson WA. The hyatt regency skywalk collapse: an EMS-based disaster response. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12(10):601–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(83)80203-0.

Paciarotti C, Cesaroni A, Bevilacqua M. The management of spontaneous volunteers: a successful model from a flood emergency in Italy. Int J Disaster Risk Reduction. 2018;1(31):260–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.05.013.

Pereira BMT, Morales W, Cardoso RG, Fiorelli R, Fraga GP, Briggs SM. Lessons learned from a landslide catastrophe in Rio de Janeiro. Brazil Am J Disaster Med. 2013;8(4):253–8. https://doi.org/10.5055/ajdm.2013.0131.

Plischke M, Wolf KH, Lison T, Pretschner DP. Telemedical support of prehospital emergency care in mass casualty incidents. Eur J Med Res. 1999;4(9):394–8 (PMID:10477508).

Postma ILE, Weel H, Heetveld MJ, van der Zande I, Bijlsma TS, Bloemers FW, et al. Patient distribution in a mass casualty event of an airplane crash. Injury. 2013;44(11):1574–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2013.04.027.

Raiter Y, Farfel A, Lehavi O, Goren OB, Shamiss A, Priel Z, et al. Mass casualty incident management, triage, injury distribution of casualties and rate of arrival of casualties at the hospitals: lessons from a suicide bomber attack in downtown Tel Aviv. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(4):225–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2007.052399.

Ran Y, Hadad E, Daher S, Ganor O, Yegorov Y, Katzenell U, et al. Triage and air evacuation strategy for mass casualty events: a model based on combat experience. Mil Med. 2011;176(6):647–51. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-10-00390.

Rauner MS, Schaffhauser-Linzatti MM, Niessner H. Resource planning for ambulance services in mass casualty incidents: a DES-based policy model. Health Care Manag Sci. 2012;15(3):254–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-012-9198-7.

Romundstad L, Sundnes Ko, Pillgram-Larsen J, Røste Gk, Gilbert M. Challenges of major incident management when excess resources are allocated: experiences from a mass casualty incident after roof collapse of a military command center. Prehospital and disaster medicine [Internet]. 2004 Jun [cited 2022 Nov 14];19(2). https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00001710

Roy N. The Asian Tsunami: PAHO disaster guidelines in action in India. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006;21(5):310–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00003939.

Salazar MK, Kelman B. Planning for biological disasters: occupational health nurses as “first responders.” AAOHN J. 2002;50(4):174–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/216507990205000411.

Service Medical du Raid null, Reuter P-G, Baker C, Loeb T. Specific stretchers enhance rapid extraction by tactical medical support teams in mass casualty incidents. Injury. 2019 Feb;50(2):358–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.12.012

Severance HW. Mass-casualty victim “surge” management. Preparing for bombings and blast-related injuries with possibility of hazardous materials exposure. N C Med J. 2002 Oct;63(5):242–6. PMID:12970967

Shah AA, Rehman A, Sayyed RH, Haider AH, Bawa A, Zafar SN, et al. Impact of a predefined hospital mass casualty response plan in a limited resource setting with no pre-hospital care system. Injury. 2015;46(1):156–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2014.08.029.

Shartar SE, Moore BL, Wood LM. Developing a Mass Casualty Surge Capacity Protocol for Emergency Medical Services to Use for Patient Distribution. South Med J. 2017 Dec;110(12):792–5. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000740

Shirm S, Liggin R, Dick R, Graham J. Prehospital preparedness for pediatric mass-casualty events. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e756-761. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2856.

Smith SW, Braun J, Portelli I, Malik S, Asaeda G, Lancet E, et al. Prehospital indicators for disaster preparedness and response: New York City emergency medical services in hurricane sandy. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;10(3):333–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2015.175.

Stănescu A, Gordon PE, Copotoiu SM, Boeriu CM. Moving toward a universal digital era in mass casualty incidents and disasters: emergency personnel’s perspective in Romania. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(4):283–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2017.0037.

Thiel CC, Schneider JE, Hiatt D, Durkin ME. 9–1-1 EMS process in the Loma Prieta earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1992;7(4):348–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00039765.

Timbie JW, Ringel JS, Fox DS, Waxman DA, Pillemer F, Carey C, et al. Allocation of scarce resources during mass casualty events. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2012;207:1–305 (PMID:24422904).

Turkdogan KA, Korkut S, Arslan E, Ozyavuz MK. First response of emergency health care system and logistics support in an earthquake. Disaster Emergency Med J. 2021;6(2):63–9. https://doi.org/10.5603/DEMJ.a2021.0013.

Veenema TG, Boland F, Patton D, O’Connor T, Moore Z, Schneider-Firestone S. Analysis of emergency health care workforce and service readiness for a mass casualty event in the Republic of Ireland. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13(2):243–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.45.

Vernon A. EMS response to mass violence. What should you know to keep you and your fellow responders safe? EMS Mag. 2010 Apr;39(4):33–6. PMID:20432984

Yafe E, Walker BB, Amram O, Schuurman N, Randall E, Friger M, et al. Volunteer first responders for optimizing management of mass casualty incidents. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13(2):287–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.56.

Khorram-Manesh A, Nordling J, Carlström E, Goniewicz K, Faccincani R, Burkle FM. A translational triage research development tool: standardizing prehospital triage decision-making systems in mass casualty incidents. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29(1):119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-021-00932-z.

Lesaffre X, Tourtier J-P, Violin Y, Frattini B, Rivet C, Stibbe O, et al. Remote damage control during the attacks on Paris: Lessons learned by the Paris Fire Brigade and evolutions in the rescue system. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Jun;82(6S Suppl 1):S107–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001438

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Partners of the NIGHTINGALE Consortium and the User Advisory Board Members who provided their valuable inputs during the different steps of the TS methodology.

Funding

This paper is supported by the NIGHTINGALE project ‘Novel InteGrated toolkit for enhanced pre-Hospital life support and Triage IN challenging And Large Emergencies’. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101021957.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weinstein, E.S., Cuthbertson, J.L., Herbert, T.L. et al. Advancing the scientific study of prehospital mass casualty response through a Translational Science process: the T1 scoping literature review stage. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 49, 1647–1660 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-023-02266-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-023-02266-0