Abstract

Background

Symptomatic calculus biliary disease is common with associated morbidity and occasional mortality, further confounded when there is concomitant common bile duct (CBD) stones. Choledocholithiasis and clearance of the duct reduces recurrent cholangitis, but the question is whether after clearance of the CBD if there is a need to perform a cholecystectomy. This meta-analysis evaluated outcomes in patients undergoing ERCP with or without sphincterotomy to determine if cholecystectomy post-ERCP clearance offers optimal outcomes over a wait-and-see approach.

Methods

A Prospero registered meta-analysis of the literature using PRISMA guidelines incorporating articles related to ERCP, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis and cholecystectomy was undertaken for papers published between 1st January 1991 and 31st May 2021. Existing research that demonstrates outcomes of ERCP with no cholecystectomy versus ERCP and cholecystectomy was reviewed to determine the related key events, complications and mortality of leaving the gallbladder in situ and removing it. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated using Review Manager Version 5.4 and meta-analyses performed using OR using fixed-effect (or random-effect) models, depending on the heterogeneity of studies.

Results

13 studies (n = 2598), published between 2002 and 2019, were included in this meta-analysis, 6 retrospective, 2 propensity score-matched retrospective studies, 3 prospective studies and 2 randomised control trials from a total of 11 countries. There were 1433 in the no cholecystectomy cohort (55.2%) and 1165 in the prophylactic cholecystectomy (44.8%) cohort. Cholecystectomy resulted in a decreased risk of cholecystitis (OR = 0.15; CI 0.07–0.36; p < 0.0001), cholangitis (OR = 0.51; CI 0.26–1.00; p = 0.05) and mortality (OR = 0.38; CI 0.16–0.9; p = 0.03). In addition, prophylactic cholecystectomy resulted in a significant reduction in biliary events, biliary pain and pancreatitis.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing CBD clearance, consideration should be given to performing prophylactic cholecystectomy to optimise outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Choledocholithiasis presents as a spectrum of significant clinical challenges including abdominal pain, jaundice, cholangitis and gallstone pancreatitis [1, 2] and is associated with increased long-term mortality. Clearance of the common bile duct is an essential part of the management of symptomatic biliary calculus disease and there is increasing evidence that clearance of the common bile duct may optimise outcomes, particularly in elderly patients [2, 3].

Following Cotton’s pioneering description of cannulation of the common bile duct (CBD) and McCune’s first successful ERCP in the mid-1970’s, ERCP has been widely adopted as the index therapeutic modality for clearance of CBD stones [4,5,6] and is most commonly performed either prior to or after operative removal of the gallstone reservoir at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There have been variable approaches to sphincterotomy during ERCP with some preferring balloon dilation and others sphincterotomy [7,8,9]. Increasingly, ERCP is performed intra-operatively with a rendezvous technique with favourable outcomes reported [10,11,12]. Primary ERCP is associated with successful clearance of CBD stones in 90%, with a complication rate approaching 10% [13, 14].

Between 10 and 20% of patients with choledocholithiasis have associated cholecystitis with potential resultant progression of cholecystitis. Upward stage migration in disease severity to fulminant or gangrenous cholecystitis is associated with excess morbidity and mortality [2, 15].

Patients who have choledocholithiasis who undergo ERCP have more difficult cholecystectomies with higher conversion rates, morbidity and associated complications [16]. Patients who undergo ERCP alone without cholecystectomy have a 20% readmission rate due to complications relating to the retained gallbladder as a stone reservoir [2].

For this reason we need clarity about the potential benefits and complications of cholecystectomy post-ERCP clearance of CBD stones. Recent meta-analysis, evaluating publications to 2019, suggested that cholecystectomy is preferred [17]. Our meta-analysis evaluated outcomes in all patients undergoing ERCP with or without sphincterotomy to determine if cholecystectomy post-ERCP clearance offers optimal outcomes over a wait-and-see approach.

Methods

Search strategy and study eligibility

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature was undertaken to incorporate articles relating to ERCP, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis and cholecystectomy. Existing research that demonstrates the outcomes of ERCP with no cholecystectomy versus ERCP and cholecystectomy was reviewed to determine the optimal outcome.

A review of all published English articles was conducted using the PubMed version of Medline, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases. To assess contemporary evidence, only studies published between 1st January 1991 and 31st May 2021 were included. A literature search was conducted using subject headings, keywords and free text terms for the keywords and their variations. The following medical subject heading (MESH) terms were included: (("cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde"[MeSH Terms] OR ("cholangiopancreatography"[All Fields] AND "endoscopic"[All Fields] AND "retrograde"[All Fields]) OR "endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography"[All Fields] OR "ercp"[All Fields]) AND ("cholecystectomy"[MeSH Terms] OR "cholecystectomy"[All Fields] OR "cholecystectomies"[All Fields]) AND ("choledocholithiasis"[MeSH Terms] OR "choledocholithiasis"[All Fields] OR ("cholangitis"[MeSH Terms] OR "cholangitis"[All Fields] OR "cholangitides"[All Fields]))) AND ((humans[Filter]) AND (1991/1/1:2021/1/1[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter])). These MeSH terms were used to search PubMed and Scopus. The reference sections of reviewed studies were examined for further papers not identified by the initial search strategy. Citations were collated with Microsoft Excel and duplicates removed.

Due to the nature of the current study, no ethical approval was sought.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The methods of the analysis and inclusion criteria were specified in advance to avoid selection bias and documented in a protocol which was registered and published with the PROSPERO database (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero, registration number: CRD42021257795 on 18th of July 2021). This meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA) statement [18].

To be included, studies had to satisfy the following pre-determined criteria: (1) include ERCP; (2) report post-ERCP complications; (3) design being a randomised controlled trial, prospective observational or retrospective cohort study; (4) reporting ten or more patients in total in sample size; (5) full text articles in the English language.

The search terms used were choledocholithiasis, cholecystectomy, ERCP and cholangitis.

Studies were not included if they (1) were designed as case reports, letters or with < 10 patients; (2) contained paediatric or pregnant populations; (4) did not have comparative cohorts.

Eligibility assessment and data extraction

We screened titles and abstracts, reviewed full texts and extracted data. Eligibility assessment was performed independently in a blinded standardised manner by three reviewers (GMG, CM, NOC). We resolved disagreements by consensus and if no agreement could be reached a fourth reviewer (AJ) decided.

Three reviewers (GMG, CM, NOC) independently assessed each published study for the quality of study design and risk of bias by using standardised pre-piloted forms and methodological index for non-randomised studies (MINORS) score [19]. A MINORS score of ≥ 16 out of 24 for comparative studies was considered the standard for inclusion.

A standardised data sheet was developed. Information was extracted from each included study on post-ERCP outcomes, study design, country, study length and cohort sizes.

The primary outcome in this study was complication rates following ERCP with no cholecystectomy vs. complications for cholecystectomy post-ERCP. Complications included cholecystitis, cholangitis, all-cause and biliary mortality, pancreatitis, biliary pain and biliary events. A biliary event consisted of (1) recurrent biliary event; (2) cholecystitis; (3) cholangitis; (4) biliary pain; (5) pancreatitis; (6) choledocholithiasis; and (7) biliary malignancy.

Statistical analysis

For comparison of complication rates of gallbladder in situ and cholecystectomy post-ERCP, odds ratios (OR) were calculated using Review Manager Version 5.4 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008). Meta-analyses were performed by computing the OR using fixed-effect (or random-effect) models, depending on the heterogeneity of studies. An OR and Confidence interval (CI) of > 1.0 indicated greater risk of an adverse event occurring in the experimental group.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic where a value greater than 50% was considered high and a random-effect model was then used to combine variables of interest [20]. OR and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each complication following ERCP, along with the p value for which a value < 0.05 represented statistical significance.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool assessed bias, as specified in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Hand-book for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [21], for the following domains; (1) random sequence generation (2), allocation concealment (3), blinding of participants and personnel (4), blinding of outcome assessment (5), incomplete outcome data (6), selective reporting bias (7) and early stopping (Fig. 1).

Results

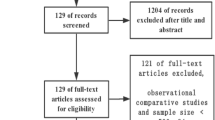

A total of 13 studies (n = 2598), published between 2002 and 2019, were included in this meta-analysis. Six retrospective, two propensity score-matched retrospective studies, three prospective studies and two randomised control trial from a total of 11 countries met inclusion criteria (Fig. 2). There were 1433 in the no cholecystectomy cohort (55.2%) and 1165 in the prophylactic cholecystectomy (44.2%) cohort. Baseline characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1.

Outcome: cholecystitis

Cholecystitis was reported in 9 out of the 13 studies; based on these studies, cholecystectomy compared to no cholecystectomy resulted in a significant decreased risk of cholecystitis (OR = 0.15; CI 0.07–0.36; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Outcome: cholangitis

Cholangitis was reported in 8 out of the 13 studies. There was a trend toward decreased risk of cholangitis in patients with cholecystectomy (12/543 [2.2%]) compared to no cholecystectomy (34/635 [5.35%]), (OR = 0.51; CI 0.26–1.00; p = 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Outcome: mortality

Five of the included studies compared overall mortality following ERCP, cholecystectomy versus no cholecystectomy with a significant reduction in mortality in those undergoing cholecystectomy (142/660 [21.5%]) compared to no cholecystectomy (237/746 [31.8%] (OR = 0.38; CI 0.16–0.9; p = 0.03) (Fig. 5).

Outcome: biliary pain

Biliary pain was reported in five included studies showing a significant decrease in biliary pain in the cholecystectomy group (18/351 [5.1%]) in comparison to the no cholecystectomy group (96/459 [20.9%]). (OR = 0.21; CI; 0.12–0.36; p < 0.000001) (Fig. 6).

Outcome: pancreatitis

Pancreatitis was illustrated in 7 out of the 13 included studies. Pancreatitis was shown to have a significant lower risk in the cholecystectomy cohort (30/717 [4.2%]) of 2.6% in comparison to the no cholecystectomy cohort (59/865 [6.8%]) following ERCP. (OR = 0.53; CI 0.34–0.84; p = 0.007) (Fig. 7).

Outcome: biliary events

Biliary events were reported in all 13 of the included studies. The cholecystectomy group (98/1165 [8.4%]) had a significantly decreased risk by 16.6% of biliary events in comparison to the no cholecystectomy group (358/1433 [25%]). (OR = 0.3; CI 0.17–0.51; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 8).

Discussion

This meta-analysis identified that patients undergoing CBD clearance followed by prophylactic cholecystectomy had a significant reduction in biliary events, biliary pain and pancreatitis.

While patients in the community may be asymptomatic with silent CBD stones, those who present to hospital are often sick with potential sepsis, pancreatitis or obstructive jaundice. This is a disease process which is frequently fuelled by the persistent presence of cholecystolithiasis. The surgical community recognises that patients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis probably do not benefit from prophylactic cholecystectomy, but the current cohort of patients studied were symptomatic presenting with complicated CBD calculus disease.

There is significant variation in current practice in performing cholecystectomy in symptomatic patients with CBD stones and the definition of early cholecystectomy which, as reported by Nakai, can vary between studies from a mean of 8 days to up to 90 days [7]. Further, the reported cholecystectomy after ERCP for choledocholithiasis is only 22% and 8% in patients aged ≥ 75 years and ≥ 85 years, respectively [30]. A reason for this could be the comorbidity burden or frailty of the elderly patients. However, the age factor alone might also influence the surgical decision. With the increase in the elderly population worldwide and the concomitant CBD stones seen in patients with biliary calculus disease [33], an active approach is recommended even in this patient population if no absolute contraindication to anaesthesia or surgery exists. Ignoring the potential problems of CBD stones may be foolish as Hakuta and colleagues identified biliary complications, related to asymptomatic CBD stones picked up on incidental imaging, with a detection rate of 6.1% at 1 year, 11% at 3 years and 17% at 5 years [34]. Möller et al. found that among patients where no measures were taken intraoperatively or planned postoperatively, the possibility for adverse outcomes varied between 15.9 and 36.9% depending on stone size in a cohort of patients diagnosed with CBD stones using IOC [35].

There has been a paradigm shift in the management of acute biliary presentations in the last decade with increasing use of index or same admission cholecystectomy [36].

Concerns have been expressed about the risk of biliary injury with early surgery, but this remains unproven, overshadowed by the increasing concern about readmission and recurrent pancreatitis in the untreated cholecystitis patient [37]. Patients presenting with acute cholecystitis have a significant increased risk of CBD stones (10%), more than three times that seen in elective cholecystectomy. In these acute situations with sepsis, there is universal support for CBD clearance to facilitate sepsis control. What is more challenging is the decision of whether to remove the gallbladder or defer cholecystectomy in patients with CBD stones. While index admission cholecystectomy is increasingly advocated, it is not suitable for all patients and, in high-risk patients, it may be associated with adverse outcomes [37]. Mytton et al. suggest in their national cohort analysis in the UK that incentive to increase the number of index admission cholecystectomies may result in the risk of overtreating patients with cholecystitis [38]. While their study did not evaluate those who had CBD stones or clearance, one should always be cautious about the risk of overtreatment and a tailored risk assessment to prophylactic cholecystectomy should be undertaken [38]. A real-world clinical management challenge is to determine the relative contribution of cholecystitis versus cholestasis to obstructing CBD stones. Imaging may help predict the degree of cholecystitis, but it can be difficult to determine whether the dilatation/oedema is purely due to an obstructive rather than an infective element. As liver function tests become increasingly abnormal, there is a greater likelihood that the key process is CBD obstruction rather than cholecystitis. Failure to remove a septic gallbladder will increase mortality. Current preoperative grading systems offer some help, but have significant limitations [39]. Many scoring systems require surgery and thus are not useful in this situation [40].

Escourrou suggested, in 1984, that deferral of cholecystectomy in patients undergoing ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) was possible [41].

In a large study with a follow-up of 24.2 (< 1–82.3) months, Archibald found that cholecystectomy was eventually required in 46 (24.7%) of the deferred cholecystectomy (DC) patients on average 6 months after ES [22]. The younger subgroup underwent eventual cholecystectomy (57.6 v. 69.4 years; p < 0.001), had a lower ASA score (ASA score of 1.98 v. 2.26; p = 0.015) and had a higher chance of residual cholecystolithiasis than those with uneventful deferral. There was a higher occurrence of recurrent pancreatitis in the deferred cholecystectomy group (30%) compared to 4.8% in the prophylactic cholecystectomy [22]. Costi and colleagues, in their small study of octogenarian patients, referred to undergo LC post-ES and CBD clearance, found that while a wait-and-see policy allowed two-thirds to avoid surgery, biliary-related events developed for every second patient, often requiring surgery with eventual poorer outcomes, with 48% developing recurrent symptoms or complications [41]. A key to determining the need for post-ERCP cholecystectomy is the presence of residual cholelithiasis in the gallbladder, especially in patients with previous pancreatitis. In their retrospective study of over 160 patients post-CBD stone removal, Cui found that the incidence of acute cholecystitis was 13.6% compared to 2.5% in those without stones [24].

Physicians must weigh up the risks of complications if the gallbladder is left in situ against the risks associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy after ERCP. Patients with ERCP clearance prior to cholecystectomy pose more technical operative difficulties leading to conversion rates of up to 20%, as reported by Lau et al. [28].

The amount of elderly patients presenting with gallstone disease is constantly rising and patients aged 80–89 years now account for 28% of male and 42% of female patients presenting with cholecystitis [43,44,45]. Elderly patients have increased comorbidities, reduced functional reserve and operating on elderly patients is associated with a higher risk of complications, higher conversion rates and a longer hospital stay [46]. In patients with acute cholecystitis, alternative strategies may include antibiotic management and percutaneous catheter drainage. However, a recent randomised controlled trial comparing percutaneous catheter drainage and laparoscopic cholecystectomy for high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis identified laparoscopic cholecystectomy to be associated with significantly lower rates of major complications and reinterventions [47].

Sousa, in a retrospective study of 131 patients (47 of whom were excluded for lack of data) with a mean age of 82 years, found a post-ERCP complication rate of 13% (8 pancreatitis, 6 cholangitis and 1 perforation) and a mortality rate of 0.7% in all patients. The same study found that 22% of patients had a cholecystectomy performed after ERCP with a median time to surgery of 209 days with a complication rate of 13% (1 empyema, 1 hemoperitoneum and 1 hypovolemic shock) and the mortality rate was 7%. Follow-up in this study revealed a new biliary event occurred in 20% of patients – 11% new ERCP, 9% cholecystitis, 9% cholangitis and 2% pancreatitis. Fewer biliary events were reported in patients who had a cholecystectomy (7% vs. 24%). No statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality (14% vs. 27%) or in mortality following biliary events (0% vs. 9%) [30]. However, it is important to highlight that in this meta-analysis the granular data on the cause and time of death was not readily available for analysis. Based on the risk of complications when deferring post-ERCP cholecystectomy, surgery should be offered to even elderly if no absolute contraindication to anaesthesia or surgery exists.

In their recent meta-analysis, McCarty found that patients with in situ gallbladders post-ES after ERCP for choledocholithiasis were found to have a 2.5-fold mortality rate and they highlighted that recurrent CBD stones occur in 37% of patients despite initial ERCP clearance [17]. Today, divergent views on the optimum CBD clearance technique exists. A recent meta-analysis by Ishii and colleagues, which compares BD and ES, identified that from collected data from the five RCTs and five NRCTs, the rate of complete CBD stone removal for the first session had a better outcome for endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by large balloon dilatation compared to endoscopic sphincterotomy (OR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.27–0.53, p < 0.01, I2 = 57%). They found that BD increased post-procedure pancreatitis but was also accompanied by less bleeding [48]

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis, which includes both ES and BD to clear the CBD, found that prophylactic cholecystectomy resulted in a decreased risk of cholecystitis, cholangitis pancreatitis and mortality and would support prophylactic cholecystectomy following endoscopic clearance of CBD.

References

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, et al. ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89(6):1075-1105.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2018.10.001.

Bass GA, Gillis AE, Cao Y, Mohseni S, European Society for Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) Cohort Studies Group. Patients over 65 years with acute complicated calculous biliary disease are treated differently-results and insights from the ESTES snapshot audit. World J Surg. 2021;45(7):2046–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-06052-0.

Saito H, Koga T, Sakaguchi M, et al. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic removal of common bile duct stones in elderly patients ≥90 years of age. Intern Med. 2019;58(15):2125–32. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.2546-18.

Kozarek RA. The past, present, and future of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13(10):620–2.

Cotton PB. Cannulation of the papilla of Vater by endoscopy and retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Gut. 1972;13(12):1014–25. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.13.12.1014.

McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1968;167(5):752–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-196805000-00013.

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Tsujino T, et al. Cholecystectomy after endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones reduced late biliary complications: a propensity score-based cohort analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(7):3014–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4592-0.

Young SH, Peng YL, Lin XH, et al. Cholecystectomy reduces recurrent pancreatitis and improves survival after endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(2):294–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-016-3284-y.

Kogure H, Kawahata S, Mukai T, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation without sphincterotomy versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile duct stones: MARVELOUS trial. Endoscopy. 2020;52(9):736–44. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1145-3377.

Mohseni S, Ivarsson J, Ahl R, et al. Simultaneous common bile duct clearance and laparoscopic cholecystectomy: experience of a one-stage approach. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45(2):337–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-0921-z.

Kenny R, Richardson J, McGlone ER, Reddy M, Khan OA. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration versus pre or post-operative ERCP for common bile duct stones in patients undergoing cholecystectomy: is there any difference? Int J Surg. 2014;12(9):989–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.06.013.

Bass GA, Pourlotfi A, Donnelly M, et al. Bile duct clearance and cholecystectomy for choledocholithiasis: definitive single-stage laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus staged procedures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90(2):240–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000002988.

Kwon CI, Song SH, Hahm KB, Ko KH. Unusual complications related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and its endoscopic treatment. Clin Endosc. 2013;46(3):251–9. https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2013.46.3.251.

Nalankilli K, Kannuthurai S, Moss A. A modern approach to ERCP: maintaining efficacy while optimising safety. Dig Endosc. 2016;28(Suppl 1):70–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12592.

Vera K, Pei KY, Schuster KM, Davis KA. Validation of a new American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) anatomic severity grading system for acute cholecystitis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(4):650–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001762.

Lee SI, Na BG, Yoo YS, Mun SP, Choi NK. Clinical outcome for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in extremely elderly patients. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015;88(3):145–51. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2015.88.3.145.

McCarty TR, Farrelly J, Njei B, Jamidar P, Muniraj T. Role of prophylactic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for biliary stone disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;273(4):667–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003977.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses PRISMA. http://prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 3 Jun 2021)

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–6.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Archibald JD, Love JR, McAlister VC. The role of prophylactic cholecystectomy versus deferral in the care of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy [published correction appears in Can J Surg. 2007 Apr;50(2):100]. Can J Surg. 2007;50(1):19–23.

Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, et al. Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9335):761–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09896-3.

Cui ML, Cho JH, Kim TN. Long-term follow-up study of gallbladder in situ after endoscopic common duct stone removal in Korean patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(5):1711–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2662-0.

Heo J, Jung MK, Cho CM. Should prophylactic cholecystectomy be performed in patients with concomitant gallstones after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones? Surg Endosc. 2015;29(6):1574–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3844-8.

Jain RK, Teasdale RL, Chattopadhyay D, et al. Cholecystectomy in patients aged 80 years and more following ERCP: is it necessary? Eur Surg. 2016;48:12–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-015-0383-z.

Kaw M, Al-Antably Y, Kaw P. Management of gallstone pancreatitis: cholecystectomy or ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(1):61–5. https://doi.org/10.1067/mge.2002.125544.

Lau JY, Leow CK, Fung TM, et al. Cholecystectomy or gallbladder in situ after endoscopic sphincterotomy and bile duct stone removal in Chinese patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(1):96–103. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.015.

Ridtitid W, Kulpatcharapong S, Piyachaturawat P, Angsuwatcharakon P, Kongkam P, Rerknimitr R. The impact of empiric endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy on future gallstone-related complications in patients with non-severe acute biliary pancreatitis whose cholecystectomy was deferred or not performed. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(10):3325–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-06622-9.

Sousa M, Pinho R, Proença L, et al. Choledocholithiasis in elderly patients with gallbladder in situ—is ERCP sufficient? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(10–11):1388–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2018.1524022.

Tsujino T, Yoshida H, Isayama H, et al. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stone removal in patients 60 years old or younger. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(10):1072–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-010-0254-0.

Zendel A, Mor E, Goitein D, Hazzan D, Nissan A, Zippel D. Cholecystectomy after endoscopic papillotomy for choledocholithiasis in the elderly—Is it necessary? Am Surg. 2019;85(11):1234–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481908501129.

Mui J, Mayne DJ, Davis KJ, Cuenca J, Craig SJ. Increasing use of intraoperative cholangiogram in Australia: is it evidence-based? ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(7–8):1534–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16912.

Hakuta R, Hamada T, Nakai Y, Oyama H, Kanai S, Suzuki T, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic bile duct stones and association of endoscopic treatment with clinical outcomes. J Gastroenterol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-019-01612-7.

Möller M, Gustafsson U, Rasmussen F, Persson G, Thorell A. Natural course vs interventions to clear common bile duct stones: data from the Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks). JAMA Surg. 2014;149(10):1008–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.249.

Nassar AHM, Ng HJ, Ahmed Z, Wysocki AP, Wood C, Abdellatif A. Optimising the outcomes of index admission laparoscopic cholecystectomy and bile duct exploration for biliary emergencies: a service model. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(8):4192–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07900-1.

NCEPOD Treat the Cause—a review of the quality of care provided to patients treated for acute pancreatitis. https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2016report1/downloads/TreatTheCause_summaryReport.pdf. (accessed on 17 Nov 2021)

Mytton J, Daliya P, Singh P, et al. Outcomes following an index emergency admission with cholecystitis: a national cohort study. Ann Surg. 2021;274(2):367–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003599.

Balvardi S, St-Louis E, Yousef Y, et al. Systematic review of grading systems for adverse surgical outcomes. Can J Surg. 2021;64(2):E196–204. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.016919 (Published 2021 Mar 26).

Sugrue M, Coccolini F, Bucholc M, Johnston A, Contributors from WSES. Intra-operative gallbladder scoring predicts conversion of laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy: a WSES prospective collaborative study. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-019-0230-9 (Published 2019 Mar 14).

Escourrou J, Cordova JA, Lazorthes F, Frexinos J, Ribet A. Early and late complications after endoscopic sphincterotomy for biliary lithiasis with and without the gall bladder ‘in situ.’ Gut. 1984;25(6):598–602. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.25.6.598.

Costi R, DiMauro D, Mazzeo A, et al. Routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in octogenarians: is it worth the risk? Surg Endosc. 2007;21(1):41–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-006-0169-2.

Pisano M, Ceresoli M, Cimbanassi S, et al. 2017 WSES and SICG guidelines on acute calculous cholecystitis in elderly population. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-019-0224-7.

Mora-Guzmán I, Di Martino M, Bonito AC, Jodra VV, Hernández SG, Martin-Perez E. Conservative management of gallstone disease in the elderly population: outcomes and recurrence. Scand J Surg. 2020;109(3):205–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496919832147.

Arthur JD, Edwards PR, Chagla LS. Management of gallstone disease in the elderly. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85(2):91–6. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588403321219849.

Kamarajah SK, Karri S, Bundred JR, et al. Perioperative outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(11):4727–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07805-z.

Loozen CS, van Santvoort HC, van Duijvendijk P, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus percutaneous catheter drainage for acute cholecystitis in high risk patients (CHOCOLATE): multicentre randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018;363:k3965. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3965 (Published 2018 Oct 8).

Ishii S, Isayama H, Ushio M, Takahashi S, Yamagata W, Takasaki Y, Suzuki A, Ochiai K, Tomishima K, Kanazawa R, Saito H, Fujisawa T, Shiina S. Best procedure for the management of common bile duct stones via the papilla: literature review and analysis of procedural efficacy and safety. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3808. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9123808.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

COI for Mr. Michael Sugrue are as follow - Education consultant with Novus Scientific, 3M and Smith and Nephew.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mc Geehan, G., Melly, C., O’ Connor, N. et al. Prophylactic cholecystectomy offers best outcomes following ERCP clearance of common bile duct stones: a meta-analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 49, 2257–2267 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-022-02070-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-022-02070-2