Abstract

Purpose

There is relatively limited large scale, long-term unified evidence to describe how quality of life (QoL) and functional outcomes are affected after polytrauma. The aim of this study is to review validated measures available to assess QoL and functional outcomes and make recommendations on how best to assess patents after major trauma.

Methods

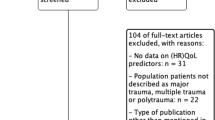

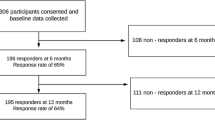

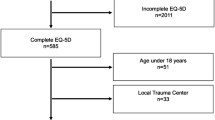

PubMed and EMBASE databases were interrogated to identify suitable patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for use in major trauma, and current practice in their use globally.

Results

Overall, 81 papers met the criteria for inclusion and evaluation. Data from these were synthesised. A full set of validated PROMs tools were identified for patients with polytrauma, as well as critique of current tools available, allowing us to evaluate practice and recommend specific outcome measures for patients following polytrauma, and system changes needed to embed this in routine practice moving forward.

Conclusion

To achieve optimal outcomes for patients with polytrauma, we will need to focus on what matters most to them, including their needs (and unmet needs). The use of appropriate PROMs allows evaluation and improvement in the care we can offer. Transformative effects have been noted in cases where they have been used to guide treatment, and if embedded as part of the wider system, it should lead to better overall outcomes. Accordingly, we have made recommendations to this effect. It is time to seize the day, bring these measures even further into our routine practice, and be part of shaping the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Moran C, et al. Changing the system—major trauma patients and their outcomes in the NHS (England) 2008–17 EClinicalMedicine. The Lancet. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.07.001.

Spreadborough S, et al. A study of outcomes of patients treated at a UK major trauma centre for moderate or severe injuries one to three years after injury. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(3):410–8.

Folkard SS, et al. Factors affecting planned return to work after trauma: a prospective descriptive qualitative and quantitative study. Injury. 2016;47(12):2664–70.

Sutherland AG, et al. The mind continues to matter: psychologic and physical recovery 5 years after musculoskeletal trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(4):228–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181ee40a9.

Sakran JV, et al. Proceedings from the consensus conference on trauma patient-reported outcome measures. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(5):819–35.

Ardolino A, Sleat G, Willett K. Outcome measurements in major trauma—Results of a consensus meeting. Injury. 2012;43(10):1662–6.

Retzer A, et al. Electronic patient reported outcomes to support care of patients with traumatic brain injury: priority study qualitative protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):

TARN. Measuring Trauma Outcomes. 2020 [cited 2020 07/09/2020]; Trauma Audit Research Network PROMs data]. Available from: https://www.tarn.ac.uk/content/downloads/19/3.%20Measure%20Trauma%20outcomes%202020.pdf.

Turner-Stokes L, NCASRI. Final report of the National Clinical Audit of Specialist Rehabilitation following major Injury. NCASRI: Northwick Park Hospital: London; 2019.

WHO. Basic Documents: WHO Constitution. Vol. 49. Geneva:Switzerland;2020

WHO. WHOQOL User Manual. Department of Mental Health, World Health Organization, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland: World Health Authority;1998

Frattali CM. Assessing functional outcomes: an overview. Semin Speech Lang. 1998;19(3):209–20.

Hoffman K, et al. Health outcome after major trauma: What are we measuring? PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):2014.

Piskur B, et al. Participation and social participation: are they distinct concepts? Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(3):211–20.

WHO, World Health Organization. How to use the ICF: A practical manual for using the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). exposure draft for comment. October, Geneva: WHO, Switzerland: World Health Authority;2013

WHO. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: the international classification of functioning, disability and health - beginner's guide. W.H. Organization ed. World Health Organisation:Geneva;2002

Rumsfeld JS. Health status and clinical practice: when will they meet? Circulation. 2002;106(1):5–7.

Pirente N, et al. Quality of life in multiply injured patients: Development of the Trauma Outcome Profile (TOP) as part of the modular Polytrauma Outcome (POLO) Chart. Eur J Trauma. 2006;32(1):44–62.

Kaske S, et al. Quality of life two years after severe trauma: A single centre evaluation. Injury. 2014;45(Supplement3):S100–5.

Gabbe. Victorian State Trauma Registry. 2020. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/patient-care/acute-care/state-trauma-system/state-trauma-registry.

Attenberger C, Amsler F, Gross T. Clinical evaluation of the Trauma Outcome Profile (TOP) in the longer-term follow-up of polytrauma patients. Injury. 2012;43(9):1566–74.

Zwingmann J, et al. Lower health-related quality of life in polytrauma patients long-term follow-up after over 5 years. Medicine. 2016;95(19):2016.

Hoffman KP, et al. Minimum data set to measure rehabilitation needs and health outcome after major trauma: application of an international framework. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52(3):331–46.

Turner GM, et al. An introduction to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(2):314–20.

McMullan C, et al. Care providers’ and patients’ attitudes toward using electronic-patient reported outcomes to support patients with traumatic brain injury: a qualitative study (PRiORiTy). Brain Inj. 2020;34(6):723–31.

NHS. NHS Digital: Background information about PROMs. 2019. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/patient-reported-outcome-measures-proms/background-information-about-proms. Accessed 1 Oct 2019.

Marshall S, Haywood K, Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(5):559–68.

Greenhalgh J, Meadows K. The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: a literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 1999;5(4):401–16.

Velikova G, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):714–24.

Espallargues M, Valderas JM, Alonso J. Provision of feedback on perceived health status to health care professionals: a systematic review of its impact. Med Care. 2000;38(2):175–86.

Rosenberg GM, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in trauma: a scoping study of published research. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018;3(1):0002021.

Weir J, et al. Does the extended glasgow outcome scale add value to the conventional glasgow outcome Scale? J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(1):53–8.

McMillan T, et al. The glasgow outcome scale — 40 years of application and refinement. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(8):477–85.

Lefering R, et al. Update of the trauma risk adjustment model of the TraumaRegister DGUTM: the Revised Injury Severity Classification, version II. Critical care (London, England). 2014;18(5):476–476.

McDowell I, Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. Third Edition, , editors. Oxford. Oxford University Press: UK; 2006. p. 765.

Mayoral AP, et al. The use of Barthel index for the assessment of the functional recovery after osteoporotic hip fracture: One year follow-up. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0212000.

Nyein K, McMichael L, Turner-Stokes L. Can a Barthel score be derived from the FIM? Clin Rehabil. 1999;13(1):56–63.

Turner-Stokes L, Siegert RJ. A comprehensive psychometric evaluation of the UK FIM + FAM. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(22):1885–95.

Li L, Wang HM, Shen Y. Chinese SF-36 Health Survey: translation, cultural adaptation, validation, and normalisation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(4):259–63.

Montazeri A, et al. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):875–82.

Üstün T, et al. ManualforWHODisabilityAssessmentSchedule: WHODAS 2.0. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010.

RAND-Healthcare. RAND 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36)—Version 1. 2020. https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Payakachat N, Ali MM, Tilford JM. Can the EQ-5D detect meaningful change? A Systematic Review Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(11):1137–54.

de Graaf MW, et al. Minimal important change in physical function in trauma patients: a study using the short musculoskeletal function assessment. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(8):2231–9.

Ponzer S, Skoog A, Bergström G. The Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment Questionnaire (SMFA): cross-cultural adaptation, validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Swedish SMFA (SMFA-Swe). Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74(6):756–63.

Attenberger C, Amsler F, Gross T. Clinical evaluation of the Trauma Outcome Profile (TOP) in the longer-term follow-up of polytrauma patients. Injury. 1566;43(9):1566–74.

Hamid K, et al. Orthopedic trauma and recovery of quality of life: an overview of the literature. Clinical Medicine Insights. 2016;7:1–8.

Kuorikoski J, et al. Finnish translation and external validation of the trauma quality of life questionnaire. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;2020:1–7.

DeWalt DA, et al. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S12–21.

Eypasch E, et al. The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index. A clinical index for measuring patient status in gastroenterologic surgery. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift für alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen. 1993;64:264–74.

Kwong E, et al. Feasibility of collecting and assessing patient-reported outcomes for emergency admissions: laparotomy for gastrointestinal conditions. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2018;5(1):e000238–e000238.

OTG. OCTS: Outcomes after chest trauma score - Key facts. 2020. Available from: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/orthopaedicsandtrauma/trauma-research/octs.aspx. Accessed Oct 10 2020.

Craxford S, Deacon C, Myint Y, Ollivere B. Assessing outcome measures used after rib fracture: A COSMIN systematic review. Injury. 2019;50(11):1816–1825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2019.07.002. Accessed 4 July 2019.

Baker E, et al. The long-term outcomes and health-related quality of life of patients following blunt thoracic injury: a narrative literature review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26(1):67.

Darwich A, et al. Outcome measures to evaluate upper and lower extremity: which scores are valid? Z Orthop Unfall. 2020;158(1):90–103.

Williams N. DASH. Occupat Med. 2014;64(1):67–8.

Beaton DE, et al. Measuring the whole or the parts? J Hand Ther. 2001;14(2):128–42.

Johanson NA, et al. American Academy of orthopaedic surgeons lower limb outcomes assessment instruments. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86(5):902–9.

Antonios T, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures used in circular frame fixation. Strat Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2019;14(1):34–44.

Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The lower extremity functional scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthop Rehabil Res Netw Phys Ther. 1999;79(4):371–83.

Yeung TSM, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the lower extremity functional scale for inpatients of an orthopaedic rehabilitation ward. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(6):468–77.

Shultz S, et al. A systematic review of outcome tools used to measure lower leg conditions. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(6):838–48.

Horng Y-S, Hou W-H, Liang H-W. Responsiveness of the modified lower extremity functional scale in patients with low back pain and sciatica: a comparison with pain intensity and the modified Roland-Morris Disability Scale. Medicine. 2019;98(14):e15105–e15105.

Mehta SP, et al. Measurement properties of the lower extremity functional scale: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016;46(3):200–16.

Hung M, et al. The factor structure of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in orthopedic trauma patients. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2015;7(6):453–9.

Bjelland I et al (2002) The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77.

Barkham M, et al. The CORE-10: a short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Couns Psychother Res. 2013;13(1):3–13.

Beck JG, et al. The impact of event scale-revised: psychometric properties in a sample of motor vehicle accident survivors. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(2):187–98.

Morina N, Ehring T, Priebe S. Diagnostic utility of the impact of event scale-revised in two samples of survivors of war. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83916.

Murphy D, et al. Exploring optimum cut-off scores to screen for probable posttraumatic stress disorder within a sample of UK treatment-seeking veterans. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1398001.

Wortmann JH, et al. Psychometric analysis of the PTSD checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(11):1392–403.

Darzi A et al. High quality care for all, NHS next stage review final report. Department of Health: Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU;2008.

NHS. NHS STANDARD CONTRACT FOR MAJOR TRAUMA SERVICE (ALL AGES): SCHEDULE 2- THE SERVICES A. SERVICE SPECIFICATIONS, N.C. Board ed. NHS England;2013.

Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences. Fewer Data On Costs Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):207–14.

Finkelstein JA, Schwartz CE. Patient-reported outcomes in spine surgery: past, current, and future directions. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;31(2):155–64.

McCormick JD, Werner BC, Shimer AL. Patient-reported outcome measures in spine surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(2):99–107.

Cruz DL, et al. Validation of the recently developed Total Disability Index: a single measure of disability in neck and back pain patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;2019:1–9.

Spiegel MA et al. (2016) Developing the total disability index based on an analysis of the interrelationships and limitations of oswestry and neck disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 41(1):74–81.

Harvey-Kelly KF, et al. Quality of life and sexual function after traumatic pelvic fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(1):28–35.

Nepola JV, et al. Vertical shear injuries: is there a relationship between residual displacement and functional outcome? J Trauma. 1999;46(6):1024–9.

Templeman D, et al. Internal fixation of displaced fractures of the sacrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:180–5.

Banierink H, et al. Patient-reported physical functioning and quality of life after pelvic ring injury: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):0233226.

Lefaivre KA, et al. What outcomes are important for patients after pelvic trauma? Subjective responses and psychometric analysis of three published pelvic-specific outcome instruments. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(1):23–7.

Majeed SA. Grading the outcome of pelvic fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(2):304–6.

Borg T, et al. Development of a pelvic discomfort index to evaluate outcome following fixation for pelvic ring injury. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2015;23(2):146–9.

Lefaivre KA, et al. Reporting and interpretation of the functional outcomes after the surgical treatment of disruptions of the pelvic ring: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(4):549–55.

Wilson JTL, et al. Reliability of postal questionnaires for the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19(9):999–1005.

Swiontkowski MF, et al. Short musculoskeletal function assessment questionnaire: validity, reliability, and responsiveness. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(9):1245–60.

Wanner JP, et al. Development of a trauma-specific quality-of-life measurement. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(2):275–81.

Ogollah R, et al. Responsiveness and minimal important change for pain and disability outcome measures in pregnancy-related low back and pelvic girdle pain. Phys Ther. 2019;99(11):1551–61.

Copay AG, Cher DJ. Is the oswestry disability index a valid measure of response to sacroiliac joint treatment? Qual Life Res. 2016;25(2):283–92.

Gerbershagen HJ, et al. Chronic pain and disability after pelvic and acetabular fractures–assessment with the Mainz Pain Staging System. J Trauma. 2010;69(1):128–36.

Zeckey C, et al. Head injury in polytrauma-Is there an effect on outcome more than 10 years after the injury? Brain Inj. 2011;25(6):551–9.

Falkenberg L et al. Long-term outcome in 324 polytrauma patients: What factors are associated with posttraumatic stress disorder and depressive disorder symptoms? Eur J Med Res 2017;22(1):44

Koller M et al. Outcome after polytrauma in a certified trauma network: comparing standard vs. maximum care facilities concept of the study and study protocol (POLYQUALY). BMC Health Services Res 2016;16:242.

Roy B (2018) PROMS 2.0 Lecture. in UK PROMS Summit 2018. De Vere Conference Centre:London;2018.

Holch P, et al. Development of an integrated electronic platform for patient self-report and management of adverse events during cancer treatment. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(9):2305–11.

Hsu C, et al. Healing in primary care: a vision shared by patients, physicians, nurses, and clinical staff. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):307–14.

Porter I, et al. Framework and guidance for implementing patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: evidence, challenges and opportunities. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5(5):507–19.

Barkham M, et al. Suitability and utility of the CORE-OM and CORE-A for assessing severity of presenting problems in psychological therapy services based in primary and secondary care settings. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:239–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andrzejowski, P., Holch, P. & Giannoudis, P.V. Measuring functional outcomes in major trauma: can we do better?. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 48, 1683–1698 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-021-01720-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-021-01720-1