Abstract

Purpose

As the most abundant neuropeptides in Central Nervous System, Substance P and Neuropeptide Y are arguably involved in the response to brain trauma. This study aims to characterize a new concept of multi-staged neuropeptide response to TBI.

Methods

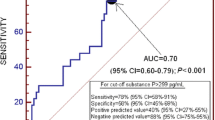

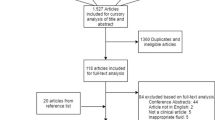

This study assessed Substance P, Neuropeptide Y, S100B, standard inflammatory parameters and ionic disturbance in TBI victims, with and without intracranial lesions, and healthy controls. In the group with intracranial lesions, blood samples were drawn until 6 h after initial trauma, at 48 h and 7 days post-TBI.

Results

An early increase in Substance P (mean 613.463 ± 49.055 SE 6 h post-TBI with brain contusions vs. 441.441 ± 22.572 SE pg/dL control group) is evident. Concerning TBI without intraparenchymatous lesions, an increase in substance P is also present (825.60 ± 23.690 SE pg/dL). Following an initial increase and subsequent fall in NPY levels (45.997 ± 4.96 SE 6 h post-TBI vs. 32.395 ± 4.056 SE 48 h post-TBI vs. 19.700 ± 1.462 SE pg/mL control group), a late increase in NPY is obvious (43.268 ± 6.260 SE pg/mL 7 day post-TBI). Post-traumatic hypomagnesemia (0.754 ± 0.015 SE 6 h post-TBI vs. 0.897 ± 0.021 SE mmol/L control group) and a peak in S100B (95.668 ± 14.102 SE 6 h post-TBI vs. 30.187 ± 3.347 SE pg/mL control group) are also present.

Conclusion

A multi-staged neuropeptide response to TBI is obvious and represents a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of intraparenchymal lesions and cerebral edema following TBI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data

Supporting data can be accessed upon request.

References

Fu T, Jing R, McFaull S, Cusimano M. Health & economic burden of traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(2):238–47.

Humphreys I, Wood R, Phillips C, Macey S. The costs of traumatic brain injury: a literature review. Clin Outcomes Res. 2013;26(5):281–7.

Sorby-Adams AJ, Marcoionni AM, Dempsey ER, Woenig JA, Turner RJ. The role of neurogenic inflammation in blood-brain disruption and development of cerebral oedema following acute central nervous system injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8).

DeKosky ST, Asken BM. Injury cascades in TBI-related neurodegeneration. Brain Inj. 2017;31(9):1177–82.

Shandra O, Winemiller A, Heithoff B, et al. Repetitive diffuse mild traumatic brain injury causes an atypical astrocyte response and spontaneous recurrent seizures. J Neurosci. 2019;39(10):1944–63.

Dobrachinski F, Gerbatin R, Sartori G, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial function and glutamatergic system are the target of guanosine effect in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(7):1318–28.

Djordevic J, Sabbir MG, Albensi BC. Traumatic brain injury as a risk factor for alzheimer’s disease: is inflammatory signaling a key player? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13(7):730–8.

Mouzon B, Chaytow H, Crynen G, et al. Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury in a mouse model produces learning and memory deficits accompanied by histological changes. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(18):2761–73.

Croall I, Smith FE, Blamire AM. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy for traumatic brain injury. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;24(5):267–74.

Stovell MG, Yan JL, Sleigh A, et al. Assessing metabolism and injury in acute human traumatic brain injury with magnetic resonance spectroscopy: current and future applications. Front Neurol. 2017;12(8):426.

Hoffman JR, Zuckerman A, Ram O, et al. Behavioral and inflammatory response in animals exposed to a low-pressure blast wave and supplemented with B-alanine. Aminoacids. 2017;49(5):871–86.

Prakash R, Carmichael ST. Blood-brain barrier breakdown and neovascularization processes after stroke and traumatic brain injury. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:556–64.

Minkkinen M, Iverson GL, Kotilainen AK, et al. Prospective validation of the scandinavian guidelines for initial management of minimal, mild, and moderate head injuries in adults. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(20):2904–12.

Lorente L, Martín M, Almeida T, et al. Serum substance P levels are associated with severity and mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2015;19:192.

Vink R, Den Heuvel C. Substance P antagonists as a therapeutic approach to improving outcome following traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7(1):74–80.

Lukacs M, Tajti J, Fulop F, Toldi J, Edvinsson L, Vecsei L. Migraine, neurogenic ınflammation, drug development - pharmacochemical aspects. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(33):3649–65.

Suvas S. Role of substance P neuropeptide in inflammation, wound healing, and tissue homeostasis. J Immunol. 2017;199(5):1543–52.

Turner R, Vink R. The role of substance P in ischaemic brain injury. Brain Sci. 2013;3(1):123–42.

Vink R, Gabrielian L, Thornton E. The role of substance P in secondary pathophysiology after traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol. 2017;8:304.

Corrigan F, Mander KA, Leonard AV, Vink R. Neurogenic inflammation after traumatic brain injury and its potentiation of classical inflammation. J Neuroinflamm. 2016;13(1):264.

Zhe Z, Hongyuan B, Wenjuan Q, Peng W, Xiaowei L, Yan G. Blockade of glutamate receptor ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis through regulation of neuropeptides. Biosci Rep. 2018;8(38):3.

Ameliorate JL, Ghabriel MN, Vink R. Magnesium enhances the beneficial effects of NK1 antagonist administration on blood-brain barrier permeability and motor outcome after traumatic brain injury. Magnes Res. 2017;30(3):88–97.

Ramamoorthy P, Wang Q, Whim M. Cell type-dependent trafficking of neuropeptide Y-containing dense core granules in CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31(41):14783–8.

Lynds R, Lyu C, Lyu GW, et al. Neuronal plasticity of trigeminal ganglia in mice following nerve injury. J Pain Res. 2017;9(10):349–57.

Silva AP, Xapelli S, Pinheiro PS, et al. Up-regulation of neuropeptide Y levels and modulation of glutamate release through neuropeptide Y receptors in the hippocampus of kainate-induced epileptic rats. J Neurochem. 2005;93(1):163–70.

Decressac M, Prestoz L, Veran J, Cantereau A, Jaber M, Gaillard A. Neuropeptide Y stimulates proliferation, migration and differentiation of neural precursors from the subventricular zone in adult mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34(3):441–9.

Geloso MC, Corvino V, Di Maria V, Marchese E, Michetti F. Cellular targets for neuropeptide Y-mediated control of adult neurogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;16(9):85.

Spencer B, Potkar R, Metcalf J, et al. Systemic Central Nervous System (CNS)-targeted delivery of neuropeptide Y (NPY) reduces neurodegeneration and increases neural precursor cell proliferation in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(4):1905–20.

Zhang Z, Ma Z, Zou W, Guo H, Liu M, Ma Y. The appropriate marker for astrocytes: comparing the distribution and expression of three astrocytic markers in different mouse cerebral regions. Biomed Res Int. 2019;24:9605265.

Thelin E, Nimer F, Frostell A, et al. A serum protein biomarker panel improves outcome prediction in human traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(20):2850–62.

Frankel M, Fan L, Yeatts SD, et al. Association of very early serum levels of S100B, glial fibrillary acidic protein, ubiquitin C-terminal hydroxilase-L1 and spectrin breakdown roduct with outcome in proTECT III. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(20):2863–71.

Mondello S, Sorinola A, Czeiter E, et al. Blood-based protein biomarkers for the management of traumatic brain injuries in adults presenting to emergency departments with mild brain injury: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2017.5182.

Thelin E, Nelson D, Bellander BM. A review of the clinical utility of sérum S100B protein levels in the assessment of traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochirur. 2017;159:209–25.

Lim L, Ho RM, Ho C. Dangers of mixed martial arts in the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):254.

Donkin JJ, Cernak I, Blumbergs PC, Vink R. A substance P antagonist reduces axonal injury and improves neurologic outcome when administered up to 12 h after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:217–24.

Park M, Oh H, Ko I, et al. Influence of mild traumatic brain injury during pediatric stage on short-term memory and hippocampal apoptosis in adult rats. J Exerc Rehabil. 2014;10(3):148–54.

Hellewell S, Semple B, Morganti-Kossmann M. Therapies negating neuroinflammation after brain trauma. Brain Res. 2016;1640:36–56.

Dikranian K, Cohen R, Macdonald C, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury to the infant mouse causes robust white matter axonal degeneration which precedes apoptotic death of cortical and thalamic neurons. Exp Neurol. 2008;211(2):551–60.

Ercole A, Thelin EP, Holst A, Bellander BM, Nelson D. Kinetic modelling of sérum S100B after traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:93.

Leonard AV, Manavis J, Blumbergs PC, Vink R. Changes in substance P and NK1 receptor immunohistochemistry following human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2014;52(1):17–23.

Giancarelli A, Birrer KL, Alban RF, Hobbs BP, Liu-deRyke X. Hypocalcemia in trauma patients receiving massive transfusion. J Surg Res. 2016;202(1):182–7.

Naghibi T, Mohajeri M, Dobakhti F. Inflammation and outcome in traumatic brain injury: does gender effect on survival and prognosis? J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(2):6–9.

Alves JL, Rato J, Silva V. Why does brain trauma research fail? World Neurosurg. 2019;130:115–21.

Sabban F, Vink R, Turner RJ. Inflammation in acute CNS injury: a focus on the role of substance P. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:703–15.

Zhang L, Bijker MS, Herzog H. The neuropeptide Y system: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications in obesity and câncer. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131(1):91–113.

Sabban EL, Laukova M, Alaluf LG, Olsson E, Serova LI. Locus coeruleus response to single-prolonged stress and early intervention with intranasal neuropeptide Y. J Neurochem. 2015;135(5):975–86.

Kaniganti T, Deogade A, Maduskar A, Mukherjee A, Guru A, Subhedar N. Sensitivity of olfactory sensory neurons to food cues is tuned to nutritional states by neuropeptide Y signalling. BioRxiv. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1101/573170.

Morin LP. Neuroanatomy of the extended circadian rhythm system. Exp Neurol. 2013;243:4–20.

Morosawa S, Iritani S, Fujishiro H, et al. Neuropeptide Y neuronal network dysfunction in the frontal lobe of a genetic mouse model of schizophrenia. Neuropeptides. 2017;62:27–35.

Angelucci F, Gelfo F, Fiore M, et al. The effect of neuropeptide Y on cell survival and neurotrophin expression in in-vitro models of Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;92(8):621–30.

Markaki E, Ellul J, Kefalopoulou Z, et al. The role of ghrelin, neuropeptide Y and leptin peptides in weight gain after deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2012;90(2):104–12.

Uckermann O, Wolf A, Franziska K, Wiedemann P, Reichenbach A, Bringmann A. Neuropeptide Y inhibits hypotonic glial cell swelling in the postischemic rat retina via glutamatergic Neuron-to-Glia Signaling. Invest Ophtalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2224.

Sampaolo S, Liguori G, Vittoria A, et al. First study on the peptidergic innervation of the brain superior sagittal sinus in humans. Neuropeptides. 2017;65:45–55.

Edyvane KA, Smet PJ, Trussell DC, Jonavicius J. Patterns of neuronal colocalisation of tyrosine hydroxylase, neuropeptide Y, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P in human uréter. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1994;48(3):241–55.

Nelson TS, Fu W, Donahue RR, et al. Facilitation of neuropathic pain by the NPY Y1 receptor-expressing subpopulation of excitatory interneurons in the dorsal horn. Sci Rep. 2019;10(9):7248.

Wang W, Xu T, Chen X, et al. NPY receptor 2 mediates NPY antidepressant effect in the mPFC of LPS rat by suppressing NLRP3 signaling pathway. Mediat Inflamm. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7898095.

He XY, Dan QQ, Wang F, et al. Protein network analysis of the serum and their functional implication in patients subjected to traumatic brain injury. Front Neurosci. 2019;12:1049.

McIntosh TK, Ferriero D. Changes in neuropeptide Y after experimental traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12(4):697–702.

Sun Z, Liu S, Kharmalov EA, Miler ER, Kelly KM. Hippocampal neuropeptide Y protein expression following controlled cortical impact and posttraumatic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;87:188–94.

Chiodera P, Volpi R, Pilla S, Cataldo S, Coiro V. Decline in circulating neuropeptide Y levels in normal elderly human subjects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143:715–6.

Johnson V, Stewart J, Begbie F, Trojanowski J, Smith D, Stewart W. Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2013;136(1):28–422.

Fatoba O, Kloster E, Saft C, Gold R, Arning L, Ellrichmann G. L22 intranasal application of NPY and NPY13–36 ameliorate disease pathology in R6/2 mouse model of huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:A97–A9898.

Sabban EL, Serova LI. Potential of intranasal neuropeptide Y (NPY) and/or melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) antagonists for preventing or treating PTSD. Mil Med. 2018;183(suppl1):408–12.

Campbell D, Raftery N, Tustin R, et al. Measurement of plasma-derived substance P: biological, methodological, and statistical considerations. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13(11):1197–203.

Corbally N, Powell D, Tipton KF. The binding of endogenous and exogenous substance-P in human plasma. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:1161–6.

Szczygielski J, Glameanu C, Müller A, et al. Changes in posttraumatic brain edema in craniectomy-selective brain hypothermia model are associated with modulation of aquaporin-4 level. Front Neurol. 2018;9:799.

Acknowledgements

Dra. Eulália Costa, for the technical support.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Research Committee (Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented for the publication of this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alves, J.L., Mendes, J., Leitão, R. et al. A multi-staged neuropeptide response to traumatic brain injury. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 48, 507–517 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01431-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01431-z