Abstract

This paper explores the use of three different two-dimensional time–frequency features for audio event classification with deep neural network back-end classifiers. The evaluations use spectrogram, cochleogram and constant-Q transform-based images for classification of 50 classes of audio events in varying levels of acoustic background noise, revealing interesting performance patterns with respect to noise level, feature image type and classifier. Evidence is obtained that two well-performing features, the spectrogram and cochleogram, make use of information that is potentially complementary in the input features. Feature fusion is thus explored for each pair of features, as well as for all tested features. Results indicate that a fusion of spectrogram and cochleogram information is particularly beneficial, yielding an impressive 50-class accuracy of over \(96\%\) in 0 dB SNR and exceeding \(99\%\) accuracy in 10 dB SNR and above. Meanwhile, the cochleogram image feature is found to perform well in extreme noise cases of \(-\,5\) dB and \(-\,10\) dB SNR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Audio event classification is a subset of machine hearing research [12] in which the classification task is essentially to identify which class of sound an unknown auditory occurrence belongs to. Much work has been done in this field in recent years, thanks to the power of advanced machine learning techniques, many of which have been borrowed from neighbouring speech research fields, particularly automatic speech recognition (ASR). As machine learning techniques have matured, the performance, scale and robustness of sound event classifiers have likewise improved—allowing more accurate classification into more sound classes in higher levels of background noise.

While most of this performance was achieved using acoustic features borrowed from the ASR domain, several researchers found that machine hearing could benefit from different types of features. In particular, Dennis [6] pioneered the use of spectrogram-like features, in which sounds could be represented as two-dimensional time–frequency images. Although he only used an SVM classifier [5], the two-dimensional nature of his features had a hidden benefit; by representing sounds as images, they allow the adoption of classification techniques inspired by the image processing research field in addition to the ASR field. This benefit enabled the present authors to introduce deep learning techniques to machine hearing, achieving good results with deep neural networks [14] and later improving on this performance by making use of convolutional neural networks [24] which are naturally well suited to image-like features.

In the literature, time–frequency image features have either been plain spectrograms [15] or derivatives such as auditory image maps (AIM) or stabilised auditory images (SAI) [22], with a number of techniques used to reduce the image dimensionality including downsampling through average pooling [25], sum pooling the marginals of sub-windows [13] or using sub-window statistics [6].

To add to spectrogram, AIM and SAI features, Xie et al. [23] investigated nonlinear data-driven adjustments to frequency bin size, yielding a warped spectrogram that achieved good performance where noise characteristics can be estimated a priori. However, the technique required a complicated two-step process to estimate noise and then derive a warped image map.

Recently, an alternative two-dimensional time–frequency image method has been used [20], called the gammatonegram or cochleogram. While relatively new to the machine hearing field, this is derived from a well-established warping, the gammatone auditory filterbank function [17]. The gammatone was originally conceived as a fit to experimental observations of mammalian cochlea frequency selectivity and thus aims to derive auditory features that are potentially bio-mimetic. The use of gammatonegram is inspired by results from Dennis [6] on one-dimensional gammatone cepstral coefficients (GTCC), which slightly outperformed other one-dimensional features such as Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), see Table 1, described later in Sect. 4.2. In those experiments, MFCC and one-dimensional gammatone features were allied to an SVM back-end classifier [6].

This paper compares the performance of spectrogram and gammatonegram features under a number of conditions using standard testing methodologies for sound event classification. We also introduce the constant-Q transform to this field [2], motivated by its performance in music analysis [7] and its evident perceptual relevance. Experimental results will show that classification performance with magnitude spectrogram features tends to be better than others under most conditions. However, exploration of the confusion characteristics of the different techniques indicates that they have complementary strengths, and hence, an investigation is made into classifications of fused features. We also introduce a region of interest (ROI)-based technique to localise sound events in the time–frequency plane based on smoothed energy. Evaluation of this method reveals that accurate temporal localisation is critical for good classification performance, but that frequency domain localisation is less important.

The energy-based ROI method, allied with a sensible time domain hold-off, will be shown to yield exceptional performance—improving upon state-of-the-art sound event detection over 50-classes [24] in clean sounds from 97.33% to over 99% and in 0 dB noise-corrupted sounds from 85.47% to over 97% when trained in noise (by contrast, MFCC features can achieve only around 16% accuracy in 0 dB noise).

2 Sound Event Classifier Design

The sound event classifiers described in this paper make use of two-dimensional time–frequency images, including the spectrogram used in the previous SVM, DNN and CNN classifier systems [5, 14, 24].

2.1 Time–Frequency Image Features

2.1.1 Spectrogram

The spectrogram is a two-dimensional time–frequency image feature formed from stacked fast Fourier transform (FFT) magnitude spectra, usually extracted from highly overlapping windows. A length N sound vector s is divided into frames of length \(w_s\) which are then windowed by a \(w_s\)-point Hamming window w(n), yielding \(s_F(n)=s(F\cdot \delta +n)\cdot w(n)\) for \(n=0 \ldots (w_s-1)\) where \(\delta \) is the shift between analysis frames. A real-valued spectral vector f for frame F is then obtained by FFT,

where k denotes frequency bins. In practice, some form of downsampling is then performed on the spectrogram (and other time–frequency image types), as discussed further in Sect. 3. The spectral magnitude vectors from each frame in a recording are then stacked to form a spectrogram image feature (SIF).

2.1.2 Cochleogram

The cochleogram (also known as gammatonegram) relies upon the gammatone warping function [17] which fits empirical observations of frequency selectivity in the mammalian cochlea, with an impulse response g(t) given by

where t is time, a is amplitude, P represents the filter order, \(\phi \) is the phase shift, \(f_\mathrm{c}\) is the central frequency (in kHz). In this paper, we define \(P=128\) and \(\phi =0\). b is the bandwidth of the gammatone filter, using the equivalent rectangular bandwidth (ERB) scale; \(f_\mathrm{erb}=24.7 \times (4.37 \times f_\mathrm{c} +1)\) and \(b=1.019 \times f_\mathrm{erb}\) [8]. For audio analysis, the gammatone filter output vectors from each frame in a recording are stacked to form a cochleogram image feature (CIF).

2.1.3 Constant-Q Transform Image

The Q-transform [2], c(k, t) over k frequency bins of time domain signal s(t) is defined as

where \(a^*_k(n)\) is the complex conjugate of time–frequency atoms which are defined by Schörkhuber et al. [19] as

and w(n) is again a window function over length \(w_s\). The major difference between this and a spectrogram is that \(w_s\) is itself a variable rather than a constant. The Constant-Q transform magnitudes over an array of overlapping analysis window form a pyramid, since resolution is frequency dependent. However, for ease of comparison and feature processing, the pyramid is rasterised to form a rectangular Constant-Q transform (CQT) feature, with the same dimensionality as the spectrogram and cochleogram. Since feature resolution varies with frequency, this evidently means that the CQT frequency bin sizes span from a single pixel to a range of pixels.

3 System Architectures and Features

3.1 System Design

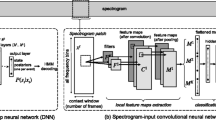

The general audio event classification architecture is shown in Fig. 1 for a feature fusion of SIF and CIF into a CNN back-end classifier. In this paper, many variants of the basic architecture will be evaluated separately, including single SIF, CIF and CQT features, dual and triple feature fusion, and back-end classification using CNN and DNN. Systems are denoted IMAGE-CLASSIFIER, and merged features are denoted IMAGE:IMAGE-CLASSIFIER, e.g. CIF-DNN and CIF:CQT-CNN.

Results for each system will be compared with state-of-the-art baselines that use SIF features with the same two neural networks, namely SIF-DNN [14] and SIF-CNN [24], respectively. These are compared with fused features, which applies the same-sized input features on multiple classifier input channels for CNN and for DNN fuses them along the time boundary. In each case, having merged the features into what is effectively a new input image, some processing needs to be applied to change this into a suitable format for neural network classification, exactly as was done for the baseline SIF systems [24]. This processing includes linear frequency downsampling, computing the frame-by-frame energy, denoising, pruning low energy frames and cropping. Pruning and cropping are necessary for the CNN to achieve convergence [24], but also significantly speed up the training process.

3.2 Image Features

For a baseline, we re-implement the best currently published SIF-based systems for 50-class sound event classification utilising DNN and CNN, SIF-DNN [14] and SIF-CNN [24]. We than adapt both to make use of cochleogram and constant-Q transform features, and evaluate with various adaptations, which will later include feature merge.

SIF evaluation Uses the baseline published in [14], where highly overlapped windows capture important instantaneous information about sound events from 16-bit waveforms sampled at 16 kHz. We use an FFT length of 64 ms with a small advance between Hamming windowed frames of 4 ms and extract the real magnitude spectra.

CIF evaluation Uses the same sample rate as SIF, with gammatone filter parameters divided into 128 frequency bands from 10 Hz to 8 kHz, in the equivalent ERB scale. The energy output of each band is then integrated over windows of 25 ms, advancing by 5 ms for successive columns.

Constant-Q transform We form a magnitude transform image at a 16 kHz sample rate from 20 Hz to Nyquist frequency over 48 frequency bins per octave using the CQT toolbox [19]. The output two-dimensional image is rasterised so that it is rectangular in shape.

Image features are constructed from all image types by downsampling in frequency to a common resolution of 52 using average pooling. A resolution of 52 has been found to perform well [14] while enjoying much lower system complexity than the original high frequency resolution. The downsampling process can be nonlinear [23], although most authors use sum or average pooling [13, 25], which is what we will adopt in this paper.

An illustration of the three features is given in Fig. 2 for two sounds from the database, a short impulsive snap, aircap_006 shown in the left column, and a longer clang, bank_023 shown in the right column. Both sounds are presented as SIF (top), CIF (middle) and CQT (bottom) and very clearly illustrate how sounds are represented differently with each feature.

In detail, to downsample the spectrogram \(f_F(n)\) of resolution \(\{F{\times }w_s/2\}\) into a \(\{F{\times }B\}\) bin frequency resolution SIF, \(\mathcal {S}_F(B)\) we use the following:

and similarly for the other time–frequency image types.

In each case, the time dimension (F frames) is variable because the input sound files in the corpus (described in Sect. 4.1) have unequal durations. Thus, a method of regularising the dimensionality is needed, since both DNN and CNN require a constant input dimension. Good performance has been obtained by ‘triggering’ equal-sized classification frames to be centred around energy peaks and pruning other areas, even for noise-corrupted sounds [24]. Energy triggering is therefore adopted as a baseline in the present paper, but we introduce additional time and energy constraints, described below. The final feature images for classification are of fixed dimension, \(52 \times 40\), irrespective of the image and classifier type being used.

3.3 Time and Energy Constraints

The test corpus consists of recordings of individual sounds of differing length. These are first transformed to the required type of time–frequency image, and then, the frequency dimensionality is reduced as mentioned above. Next, the frame-wise time domain energy, E(m), is computed:

The highest energy peak is identified as a seed of the first region of interest (ROI), and then, the search is repeated for additional high energy peaks located at least h frames away from a previously identified peak. If the energy of the second peak is less than e times the energy of the first peak, it is discarded and the search terminated; otherwise, it is identified as the seed point of a second ROI. The process continues until the maximum number of ROIs is reached, or no more candidate ROIs can be found. In Sect. 5.1, we evaluate \(h=1, 3, 5, 8\), and set \(e=0.1\) which in practice yields no more than \(M=9\) ROIs per recording, across all sound classes. However, around 80% of sounds in the corpus are short enough duration that they can be adequately represented by a single ROI.

3.4 Image Selection

A single-feature image of dimension \(\{L{\times }B\}\) is obtained from around each of M ROI seed points \(m_{\max }^M\), as illustrated in Fig. 3. Then the features, \(\mathbf {R}\), are obtained by \(\mathbf {R}=\mathcal {S}[{m^M_{{\max } - L/2}}:{m^M_{{\max } + L/2 + 1}},1:B]\) for all M.

We also evaluated cropping feature images directly from the full dimensionality time–frequency images (rather than the downsampled image, also shown in Fig. 3). In that case, the ROI is localised in both time and frequency domains: First, the highest energy frame is identified and then the highest energy frequency region within that frame. This ROI point marks the centre of the final \(\{L \times B\}\) feature window to be cropped from the larger image. By contrast, the original method found an ROI only in the time domain since the frequency dimensionality was already downsampled to 52. All feature windows in the original method therefore spanned the entire frequency range but are localised in time, whereas in the cropping method, the feature windows are localised in both time and frequency (hence they only span part of the frequency range).

In evaluations for all image types, the performance of the cropping method was slightly degraded (by around 1–2% overall). In detail, it tended to perform better than baseline in high levels of noise and worse than baseline when classifying clean sounds. However, given poorer overall performance, this paper adopts the former method, where the ROI is localised in time only.

3.5 Deep Neural Network

A DNN is a feedforward network of multiple hidden layers, each consisting of a number of neurons defined with weights and biases. It is constructed from a stack of individual pre-trained restricted Boltzmann machine (RBM) pairs which are then fine tuned using the back propagation algorithm in an end-to-end fashion. The weight associated with each neuron is updated by stochastic gradient descent during training [10]. Since the standard classification task in this paper has 50 sound classes, we use softmax as an activation function from the output layer of size 50, with cross-entropy as the cost function. We apply a dropout and implement rectified linear units (ReLU) [9] to avoid over-fitting.

In detail, we use a four-layer network with two hidden layers comprising 512 and 1024 nodes, respectively. The input vector has \(52 \times 40=2080\) dimensions, and the output layer has 50 nodes, determined by the number of classes in the evaluation task. The structure is thus \(2080-512-1024-50\), which is identical to that in [24], apart from the system utilising merged input features (described later).

3.6 Convolutional Neural Network

CNNs are regarded as a successful variant of deep neural networks. Instead of using fully connected hidden layers, the CNN introduces a network structure that includes convolution and pooling layers to achieve translation invariance and tolerance to minor data differences in patterns [1]. The input data for the CNN are organised as a number of feature maps, each of which can be viewed as a multidimensional array distributed over several dimensional indices (for example two dimensions in an image). In the convolution layer, by applying multiple local filters across the input data, new feature maps can be obtained. Pooling layers downsample the input to reduce dimensionality using average or max pooling. At the output of a stack of several convolution and pooling layers, fully connected layers combine the extracted features. All units in the same feature map share the same weights but receive input from different locations of the lower layer, reducing the number of trainable parameters as well as improving the generalisation ability of the network [1]. Like the DNN, the CNNs use dropout and ReLU techniques to avoid over-fitting, and we insert a batch normalisation layer [11] after pooling.

In detail, we use two convolutional layers with outputmaps of size 50 and 500, a convolution kernel size of \(5{\times }5\) and a subsampling kernel size of \(2{\times }2\). The fully connected final convolutional layer comprises 1024 hidden nodes. As in the DNN system, there are 50 output nodes with the output being formed using softmax and an input dimension of \(52 \times 40\). The CNN toolbox [21] is used for all experiments.

3.7 Denoising

We also test a low complexity noise estimation and spectral subtraction method. This begins by determining the mean frequency response of the first and last few (fixed at 3) frames from each feature image. Since most recordings begin and end with silence, this effectively forms a crude estimate of background noise, \(\zeta (n)={1 \over 6}\sum _{k=0}^{2}\{{\mathcal {S}_k(n)+\mathcal {S}_{F-k}(n)}\}\). The noise frequency spectral estimate is then subtracted from every frame in the image feature to remove stationary noise from each frame, \(\mathcal {S}'_m(n)=\mathcal {S}_m(n)-\zeta (n) \quad \hbox {for} \,\, m=0 \dots F\).

3.8 Smaller Network

Each of the CNN systems described in this paper requires significant training time, even using a high-performance GPU. We therefore explored the use of a smaller network structure. For experiments denoted with the suffix ‘-small’ and where specified, we reduced the feature maps from 500 to 50 and 64 to 32, respectively. We also decreased the number of hidden nodes in the fully connected layer from 1024 to 512. This halved the training time, at the cost of only a slight degradation in performance (explored in Sect. 5.1).

4 Testing Methodology

4.1 Corpus

A total of 80 recordings are randomly selected from 50 sound classes chosen from the Real World Computing Partnership (RWCP) Sound Scene Database in Real Acoustic Environments [16] following the method of Dennis [6] and in accordance with other systems in the literature [3, 4, 14, 18, 23,24,25]. Of the 80 recordings in each class, 50 are used for training and 30 for testing. Therefore, a total of 2500 recordings are available for training and 1500 for testing. Each recording contains a single example sound, captured with high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), typically having short lead-in and lead-out silence sections. For evaluation of robustness, these clean recordings are corrupted by noise using four background noise environments selected from the NOISEX-92 database (namely ‘Destroyer Control Room,’ ‘Speech Babble,’ ‘Factory Floor 1’ and ‘Jet Cockpit 1’), again following [6]. We adapt the same mismatched evaluation method as most other authors, where classifiers are trained using clean sounds without pre-processing or noise removal. Evaluations repeat for clean sounds and those corrupted by different levels of additive noise, scored separately.

4.2 Related Work

A selection of audio event classification systems evaluated using the same corpus, noise and test procedure is shown in Table 1 (from [5, 6, 14, 24]). The ‘mean’ column presents the average score of all tested noise conditions, providing a convenient single metric of noise robust performance. The same testing method is used throughout this paper, although later we will further explore the robustness of the main systems by extending the tests to include more challenging evaluations in \(-5\) dB and \(-10\) dB SNR conditions.

5 Results

5.1 Single-Feature Performance

5.1.1 Baseline Accuracy for SIF and CIF Features

The best performing methods in Table 1 under robust conditions were the SIF-based approaches utilising DNN and CNN classifiers with spectrogram image features (SIF). We evaluate these baseline SIF systems further, with results shown in Table 2: Firstly the effect of the simple spectral subtraction denoising system on the SIF-DNN baseline, which is to improve accuracy under noisy conditions (from 85.1 to 87.5% in 0 dB SNR) at the expense of significant accuracy reduction for clean sounds.

The same trend is seen for the SIF-CNN baseline, but with a far greater improvement under noisy conditions (85.5–93.8%), and much smaller penalty for clean sounds. Unlike the DNN, the mean SIF-CNN score is improved by denoising. This is probably due to the fact that the spectral subtraction applies globally, extending beyond the receptive field size of the CNN, and thus works in a complementary way to the CNN training. The SIF-CNN-small system of Sect. 3.8, which also includes denoising, causes a marginal classification accuracy reduction in noise but performs well for clean sounds.

We also repeat the same evaluations using a cochleogram image feature (CIF). Comparing like-for-like conditions and setups, CIF outperforms SIF only in small and denoised systems. But the results show that almost all SIF systems are better than CIF in 0 dB noise. Thus, CIF may not be a good choice of single feature for robust audio event classification, nor for use with a DNN back-end classifier.

5.1.2 Baseline Accuracy for SIF and CIF Features

The best performing classifier architecture from Table 2, the CNN (although the smaller variant), is now explored further in terms of the minimum separation of ROIs, h from Sect. 3.3. We evaluate performance in this way for the CNN classifier with SIF and with CIF but also include the constant-Q transform image (CQT) as discussed in Sect. 3.

Results indicate that SIF has best performance, followed by CIF and then CQT which lags significantly. SIF and CQT ‘prefer’ a smaller feature separation than CIF, which indicates that the CNN classifier is able to make use of additional information gained from the fine detail encoded in closely separated features. For SIF, this means frame overlap; for CQT, because the window size is frequency dependent, this implies that high-resolution high frequency information is useful to the CNN (Table 3).

In terms of robustness, the CQT is clearly far less robust to high levels of noise than the other features, and performance in noise favours having less separation between features.

5.2 Combined Feature Performance

These experiments in Sect. 5.1 show differing strengths and weaknesses of each feature, but also reveal that the features respond differently to noise and to spacing. We already know from Fig. 2 that the three image features reveal quite different two-dimensional image maps from the same sounds, and thus, we conjecture that different image features may not only respond differently to background noise, but also be better or worse suited to individual sound classes. To explore this further, we plot the normalised confusion matrices from the CIF-CNN and SIF-CNN classifiers in 0 dB SNR noise, in Fig. 4 (left and right plots, respectively). These plots show how each recording from the 50 different classes was actually classified in practice. If classification was perfect, then the score is 1.0 on the diagonal axis.

What is immediately apparent from the confusion matrices is that there is very little correlation between per-class performance for the two-feature types; classes that are poorly classified by CIF are much better classified by SIF, and vice versa. Secondly, we note that in both cases there are a handful of classes that contribute the most errors. Both image features are extremely good at classifying the majority of classes, but fail quite badly on just a few classes, which are different between the feature types.

This provides sufficient evidence that classification on fused features may yield improved performance. We therefore evaluate the performance of a CNN classifier operating on each possible pair of feature types (as shown in Fig. 1), namely CIF:CQT, CQT:SIF and CIF:SIF, where ‘:’ denotes a fusion in which the identically sized and aligned features are presented on different input channels to the CNN, with all training and testing proceeding using the new feature, but otherwise unchanged from the single-feature evaluation. We then repeat the evaluation with a system that fuses all three features, SIF:CIF:CQT.

Results are presented in Table 4, which lists the best performing single-feature classifier results (top), the three two-feature results (middle) and the 3 feature result (bottom). For this evaluation, we extend the results table to the right with two more extreme noise cases. Figures are then given for the average score over the traditional noise levels {clean ...0 dB}, denoted mean\(_4\), as well as over the extended range of {clean ...− 10 dB}, denoted mean\(_6\).

Considering first the two-feature fusion results, it is clear that the CIF:SIF combination outperforms all other feature combinations for every condition shown, although a single-feature CIF works better in the extreme \(-\,10\) dB SNR case, and a single-feature SIF is marginally better at 10 dB SNR. The former result is interesting, because although we knew from Sect. 5.1 that SIF outperforms CIF in all levels of noise from {clean ...0 dB}, we now see from Table 4 that CIF may have an advantage over SIF under extremely high noise conditions—outperforming single-feature SIF at both \(-\,5\) and \(-\,10\) dB SNR.

CQT, by contrast, does not appear to provide an advantage in either high nor low noise conditions. When the CQT feature is fused with the other two, to form a 3-feature input CNN architecture, performance is degraded compared to the two-feature or indeed single feature SIF systems. The CQT may have other advantages in machine hearing and in particular may suit different classifiers or evaluation aims, but as a two-dimensional input feature for noise robust sound event classification with CNN, CIF and SIF, both perform better in all situations.

6 Conclusion

This paper first evaluated single-feature two-dimensional time–frequency image classification of sound events using spectrogram, cochleogram and constant-Q transform with back-end CNN and DNN classifiers. In particular, it assessed systems in terms of noise robust classification accuracy of isolated audio events from the popular 50-class evaluation of RWCP-SSD sounds, first defined by Dennis [6]. Results confirm previous findings that spectrogram image features (SIF) allied with a CNN classifier are most noise robust in noise levels ranging from light 20 dB SNR to highly corrupted 0 dB SNR. Extending the evaluation to more extreme levels of noise, however, reveals that CIF features may have an advantage in very high noise environments, outperforming SIF in \(-\,5\) and \(-\,10\) dB SNR noise evaluations.

Confusion plots of SIF and CIF systems revealed the interesting fact that the two features had clear affinity for different sets of sound classes. When they failed to classify particular classes correctly, this occurred for different classes in each case—indicating that the classifiers made use of the quite different (potentially complementary) information when operating on those two features. This motivated an investigation into feature fusion, which revealed that an advantage could be gained through the fusion of SIF and CIF features with a CNN back-end classifier. However, it was found that inclusion of the CQT feature was detrimental to performance. The fusion of all three features, by contrast, failed to improve upon the two-feature fusion results.

The best performing system, the CIF:SIF-CNN classifier, obtained a performance on the traditional mean score over clean, 20, 10, 0 dB conditions of \(98.75\%\), more than \(2\%\) above previously published state-of-the-art systems. Impressively, it was able to achieve \(96.96\%\) accuracy in 0 dB SNR noise.

References

O. Abdel-Hamid, A. Mohamed, H. Jiang, L. Deng, G. Penn, D. Yu, Convolutional neural networks for speech recognition. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 22(10), 1533–1545 (2014)

J.C. Brown, Calculation of a constant Q spectral transform. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89(1), 425–434 (1991)

J. Dennis, H.D. Tran, E.S. Chng, Image feature representation of the subband power distribution for robust sound event classification. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 21(2), 367–377 (2013)

J. Dennis, H.D. Tran, E.S. Chng, Overlapping sound event recognition using local spectrogram features and the generalised Hough transform. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 34(9), 1085–1093 (2013)

J. Dennis, H.D. Tran, H. Li, Spectrogram image feature for sound event classification in mismatched conditions. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 18(2), 130–133 (2011)

J.W. Dennis, Sound event recognition in unstructured environments using spectrogram image processing, Ph.D. thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2014

B. Fuentes, A. Liutkus, R. Badeau, G. Richard, Probabilistic model for main melody extraction using constant-Q transform, in 2012 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (2012), pp. 5357–5360. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2012.6289131

B.R. Glasberg, B.C. Moore, Derivation of auditory filter shapes from notched-noise data. Hear. Res. 47(1–2), 103–138 (1990)

X. Glorot, A. Bordes, Y. Bengio, Deep sparse rectifier neural networks, in International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (2011), pp. 315–323

G.E. Hinton, S. Osindero, Y.W. Teh, A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 18(7), 1527–1554 (2006)

S. Ioffe, C. Szegedy, Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift, in Proceedings of ICML (2015), pp. 448–456

R.F. Lyon, Machine hearing: an emerging field. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 27(5), 131–139 (2010)

R.F. Lyon, M. Rehn, S. Bengio, T.C. Walters, G. Chechik, Sound retrieval and ranking using sparse auditory representations. Neural Comput. 22(9), 2390–2416 (2010)

I. McLoughlin, H.M. Zhang, Z.P. Xie, Y. Song, W. Xiao, Robust sound event classification using deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 23, 540–552 (2015)

I.V. McLoughlin, Speech and Audio Processing: A MATLAB-Based Approach (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016)

S. Nakamura, K. Hiyane, F. Asano, T. Yamada, T. Endo, Data collection in real acoustical environments for sound scene understanding and hands-free speech recognition, in EUROSPEECH (1999), pp. 2255–2258

R. Patterson, I. Nimmo-Smith, J. Holdsworth, P. Rice, An efficient auditory filterbank based on the gammatone function, in A Meeting of the IOC Speech Group on Auditory Modelling at RSRE, vol 2 (1987)

H. Phan, L. Hertel, M. Maaß, A. Mertins, Robust audio event recognition with 1-max pooling convolutional neural networks. CoRR (2016). arXiv:1604.06338

C. Schörkhuber, A. Klapuri, N. Holighaus, M. Dörfler, A Matlab toolbox for efficient perfect reconstruction time–frequency transforms with log-frequency resolution, in Audio Engineering Society Conference: 53rd International Conference: Semantic Audio (Audio Engineering Society, 2014)

R.V. Sharan, T.J. Moir, Robust acoustic event classification using deep neural networks. Inf. Sci. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2017.02.013. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020025517304553

A. Vedaldi, K. Lenc, Matconvnet: convolutional neural networks for Matlab, in Proceedings of the 23rd Annual ACM Conference on Multimedia Conference (ACM, 2015), pp. 689–692

T.C. Walters, Auditory-based processing of communication sounds, Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2011

Z. Xie, I. McLoughlin, H. Zhang, Y. Song, W. Xiao, A new variance-based approach for discriminative feature extraction in machine hearing classification using spectrogram features. Digit. Signal Process. 54, 119–128 (2016)

H. Zhang, I. McLoughlin, Y. Song, Robust sound event recognition using convolutional neural networks, in 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), vol 2635 (IEEE, 2015), pp. 559–563

H. Zhang, I. McLoughlin, Y. Song, Robust sound event detection in continuous audio environments, in Proceedings of Interspeech (2016)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McLoughlin, I., Xie, Z., Song, Y. et al. Time–Frequency Feature Fusion for Noise Robust Audio Event Classification. Circuits Syst Signal Process 39, 1672–1687 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-019-01203-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-019-01203-0