Abstract

Sebaceous glands (SG) are exocrine glands that release their product by holocrine secretion, meaning that the whole cell becomes a secretion following disruption of the membrane. SG may be found in association with a hair follicle, forming the pilosebaceous unit, or as modified SG at different body sites such as the eyelids (Meibomian glands) or the preputial glands. Depending on their location, SG fulfill a number of functions, including protection of the skin and fur, thermoregulation, formation of the tear lipid film, and pheromone-based communication. Accordingly, SG abnormalities are associated with several diseases such as acne, cicatricial alopecia, and dry eye disease. An increasing number of genetically modified laboratory mouse lines develop SG abnormalities, and their study may provide important clues regarding the molecular pathways regulating SG development, physiology, and pathology. Here, we summarize in tabulated form the available mouse lines with SG abnormalities and, focusing on selected examples, discuss the insights they provide into SG biology and pathology. We hope this survey will become a helpful information source for researchers with a primary interest in SG but also as for researchers from unrelated fields that are unexpectedly confronted with a SG phenotype in newly generated mouse lines.

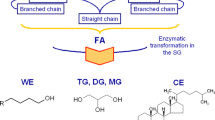

Reproduced with permission from [18]

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schneider MR (2012) Genetic mouse models for skin research: strategies and resources. Genesis 50(9):652–664

Sundberg JP (1994) Handbook of mouse mutations with skin and hair abnormalities. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Nakamura M, Sundberg JP, Paus R (2001) Mutant laboratory mice with abnormalities in hair follicle morphogenesis, cycling, and/or structure: annotated tables. Exp Dermatol 10(6):369–390

Nakamura M et al (2013) Mutant laboratory mice with abnormalities in hair follicle morphogenesis, cycling, and/or structure: an update. J Dermatol Sci 69(1):6–29

Nakamura M et al (2002) Mutant laboratory mice with abnormalities in pigmentation: annotated tables. J Dermatol Sci 28(1):1–33

Zouboulis CC et al (2008) Frontiers in sebaceous gland biology and pathology. Exp Dermatol 17(6):542–551

Kurokawa I et al (2009) New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol 18:821–832

Schneider MR, Paus R (2010) Sebocytes, multifaceted epithelial cells: lipid production and holocrine secretion. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42(2):181–185

Toth BI et al (2011) “Sebocytes’ makeup”: novel mechanisms and concepts in the physiology of the human sebaceous glands. Pflugers Arch 461(6):593–606

Page ME et al (2013) The epidermis comprises autonomous compartments maintained by distinct stem cell populations. Cell Stem Cell 13(4):471–482

Veniaminova NA et al (2013) Keratin 79 identifies a novel population of migratory epithelial cells that initiates hair canal morphogenesis and regeneration. Development 140(24):4870–4880

Dahlhoff M et al (2013) PLIN2, the major perilipin regulated during sebocyte differentiation, controls sebaceous lipid accumulation in vitro and sebaceous gland size in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830(10):4642–4649

Camera E et al (2014) Perilipin 3 modulates specific lipogenic pathways in SZ95 sebocytes. Exp Dermatol 23(10):759–761

Dahlhoff M et al (2014) Angiopoietin-like 4, a protein strongly induced during sebocyte differentiation, regulates sebaceous lipogenesis but is dispensable for sebaceous gland function in vivo. J Dermatol Sci 75(2):148–150

Dahlhoff M et al (2015) EGFR/ERBB receptors differentially modulate sebaceous lipogenesis. FEBS Lett 589(12):1376–1382

Dahlhoff M, Zouboulis CC, Schneider MR (2016) Expression of dermcidin in sebocytes supports a role for sebum in the constitutive innate defense of human skin. J Dermatol Sci 81(2):124–126

Thody AJ, Shuster S (1989) Control and function of sebaceous glands. Physiol Rev 69(2):383–416

Schneider MR (2016) Lipid droplets and associated proteins in sebocytes. Exp Cell Res 340(2):205–208

Schneider MR, Paus R (2014) Deciphering the functions of the hair follicle infundibulum in skin physiology and disease. Cell Tissue Res 358(3):697–704

Smith KR, Thiboutot DM (2008) Thematic review series: skin lipids. Sebaceous gland lipids: friend or foe? J Lipid Res 49(2):271–281

Frances D, Niemann C (2012) Stem cell dynamics in sebaceous gland morphogenesis in mouse skin. Dev Biol 363(1):138–146

Knop E et al (2011) The international workshop on Meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the Meibomian gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52(4):1938–1978

Smits R et al (1999) Apc1638T: a mouse model delineating critical domains of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein involved in tumorigenesis and development. Genes Dev 13(10):1309–1321

Johnson KR et al (1998) A new spontaneous mouse mutation of Hoxd13 with a polyalanine expansion and phenotype similar to human synpolydactyly. Hum Mol Genet 7(6):1033–1038

Rudali G, Roudier R, Vives C (1974) The preputial gland of the male mouse. Pathol Biol (Paris) 22(10):895–899

Bronson FH, Caroom D (1971) Preputial gland of the male mouse; attractant function. J Reprod Fertil 25(2):279–282

Bek S et al (2015) Compromised epidermal barrier stimulates Harderian gland activity and hypertrophy in ACBP−/− mice. J Lipid Res 56(9):1738–1746

Payne AP (1994) The Harderian gland: a tercentennial review. J Anat 185(Pt 1):1–49

Finkle D et al (2004) HER2-targeted therapy reduces incidence and progression of midlife mammary tumors in female murine mammary tumor virus huHER2-transgenic mice. Clin Cancer Res 10(7):2499–2511

Nelson JD et al (2011) The international workshop on Meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52(4):1930–1937

Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S (2012) Acne vulgaris. Lancet 379(9813):361–372

Well D (2013) Acne vulgaris: a review of causes and treatment options. Nurse Pract 38(10):22–31

McElwee KJ (2008) Etiology of cicatricial alopecias: a basic science point of view. Dermatol Ther 21(4):212–220

Ohyama M (2012) Primary cicatricial alopecia: recent advances in understanding and management. J Dermatol 39(1):18–26

Schneider MR (2015) Fifty years of the asebia mouse: origins, insights and contemporary developments. Exp Dermatol 24(5):340–341

Sundberg JP et al (2000) Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol 156(6):2067–2075

Gates AH, Karasek M (1965) Hereditary absence of sebaceous glands in the mouse. Science 148(3676):1471–1473

Marnett LJ et al (1999) Arachidonic acid oxygenation by COX-1 and COX-2. Mechanisms of catalysis and inhibition. J Biol Chem 274(33):22903–22906

Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM (2000) Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem 69:145–182

Neufang G et al (2001) Abnormal differentiation of epidermis in transgenic mice constitutively expressing cyclooxygenase-2 in skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98(13):7629–7634

Muller-Decker K et al (2003) Expression of cyclooxygenase isozymes during morphogenesis and cycling of pelage hair follicles in mouse skin: precocious onset of the first catagen phase and alopecia upon cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression. J Invest Dermatol 121(4):661–668

Bol DK et al (2002) Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in the skin of transgenic mice results in suppression of tumor development. Cancer Res 62(9):2516–2521

Tsujii M, DuBois RN (1995) Alterations in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial cells overexpressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2. Cell 83(3):493–501

Watt FM, Frye M, Benitah SA (2008) MYC in mammalian epidermis: how can an oncogene stimulate differentiation? Nat Rev Cancer 8(3):234–242

Arnold I, Watt FM (2001) c-Myc activation in transgenic mouse epidermis results in mobilization of stem cells and differentiation of their progeny. Curr Biol 11(8):558–568

Foster KW et al (2005) Induction of KLF4 in basal keratinocytes blocks the proliferation-differentiation switch and initiates squamous epithelial dysplasia. Oncogene 24(9):1491–1500

Braun KM et al (2003) Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development 130(21):5241–5255

Bull JJ et al (2005) Ectopic expression of c-Myc in the skin affects the hair growth cycle and causes an enlargement of the sebaceous gland. Br J Dermatol 152(6):1125–1133

Zanet J et al (2005) Endogenous Myc controls mammalian epidermal cell size, hyperproliferation, endoreplication and stem cell amplification. J Cell Sci 118(Pt 8):1693–1704

Halter SA et al (1992) Distinctive patterns of hyperplasia in transgenic mice with mouse mammary tumor virus transforming growth factor-alpha. Characterization of mammary gland and skin proliferations. Am J Pathol 140(5):1131–1146

Li Y et al (2015) Transgenic expression of human amphiregulin in mouse skin: Inflammatory epidermal hyperplasia and enlarged sebaceous glands. Exp Dermatol

Dahlhoff M et al (2010) Epigen transgenic mice develop enlarged sebaceous glands. J. Invest Dermatol 130(2):623–626

Dahlhoff M et al (2014) Overexpression of epigen during embryonic development induces reversible, epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent sebaceous gland hyperplasia. Mol Cell Biol 34(16):3086–3095

Dong F et al (2015) Perturbed Meibomian gland and tarsal plate morphogenesis by excess TGFalpha in eyelid stroma. Dev Biol 406(2):147–157

Luetteke NC et al (1993) TGF alpha deficiency results in hair follicle and eye abnormalities in targeted and waved-1 mice. Cell 73(2):263–278

Zouboulis CC, Schagen S, Alestas T (2008) The sebocyte culture: a model to study the pathophysiology of the sebaceous gland in sebostasis, seborrhoea and acne. Arch Dermatol Res 300(8):397–413

Dahlhoff M et al (2016) Sebaceous lipids are essential for water repulsion, protection against UVB-induced apoptosis, and ocular integrity in mice. Development

Cong L et al (2013) Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339(6121):819–823

Hinde E et al (2013) A practical guide for the study of human and murine sebaceous glands in situ. Exp Dermatol 22(10):631–637

Guillou H et al (2010) The key roles of elongases and desaturases in mammalian fatty acid metabolism: insights from transgenic mice. Prog Lipid Res 49(2):186–199

Mustonen T et al (2003) Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by Ectodysplasin-A1. Dev Biol 259(1):123–136

Cui CY et al (2003) Inducible mEDA-A1 transgene mediates sebaceous gland hyperplasia and differential formation of two types of mouse hair follicles. Hum Mol Genet 12(22):2931–2940

Sugawara T et al (2012) Reduced size of sebaceous gland and altered sebum lipid composition in mice lacking fatty acid binding protein 5 gene. Exp Dermatol 21(7):543–546

Panchal H et al (2007) Neuregulin3 alters cell fate in the epidermis and mammary gland. BMC Dev Biol 7:105

Plikus M et al (2004) Morpho-regulation of ectodermal organs: integument pathology and phenotypic variations in K14-Noggin engineered mice through modulation of bone morphogenic protein pathway. Am J Pathol 164(3):1099–1114

Guha U et al (2004) Bone morphogenetic protein signaling regulates postnatal hair follicle differentiation and cycling. Am J Pathol 165(3):729–740

Qiu W et al (2011) Conditional activin receptor type 1B (Acvr1b) knockout mice reveal hair loss abnormality. J. Invest Dermatol 131(5):1067–1076

Yang J et al (2010) Fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in keratinocytes control the epidermal barrier and cutaneous homeostasis. J Cell Biol 188(6):935–952

Grose R et al (2007) The role of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b in skin homeostasis and cancer development. EMBO J 26(5):1268–1278

Cascallana JL et al (2005) Ectoderm-targeted overexpression of the glucocorticoid receptor induces hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Endocrinology 146(6):2629–2638

Carroll JM, Romero MR, Watt FM (1995) Suprabasal integrin expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice results in developmental defects and a phenotype resembling psoriasis. Cell 83(6):957–968

Brakebusch C et al (2000) Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on beta 1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. EMBO J 19(15):3990–4003

Norum JH et al (2015) A conditional transgenic mouse line for targeted expression of the stem cell marker LGR5. Dev Biol 404(2):35–48

Allen M et al (2003) Hedgehog signaling regulates sebaceous gland development. Am J Pathol 163(6):2173–2178

Estrach S et al (2006) Jagged 1 is a beta-catenin target gene required for ectopic hair follicle formation in adult epidermis. Development 133(22):4427–4438

Karnik P et al (2009) Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J. Invest Dermatol 129(5):1243–1257

Chang SH et al (2009) Enhanced Edar signalling has pleiotropic effects on craniofacial and cutaneous glands. PLoS One 4(10):e7591

Keisala T et al (2009) Premature aging in vitamin D receptor mutant mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 115(3–5):91–97

Lo Celso C, Prowse DM, Watt FM (2004) Transient activation of beta-catenin signalling in adult mouse epidermis is sufficient to induce new hair follicles but continuous activation is required to maintain hair follicle tumours. Development 131(8):1787–1799

Gat U et al (1998) De novo hair follicle morphogenesis and hair tumors in mice expressing a truncated beta-catenin in skin. Cell 95(5):605–614

House JS et al (2010) C/EBPalpha and C/EBPbeta are required for sebocyte differentiation and stratified squamous differentiation in adult mouse skin. PLoS One 5(3):e9837

Olson LE et al (2005) Barx2 functions through distinct corepressor classes to regulate hair follicle remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(10):3708–3713

Hwang J et al (2008) Dlx3 is a crucial regulator of hair follicle differentiation and cycling. Development 135(18):3149–3159

Petersson M et al (2011) TCF/Lef1 activity controls establishment of diverse stem and progenitor cell compartments in mouse epidermis. EMBO J 30(15):3004–3018

Niemann C et al (2002) Expression of DeltaNLef1 in mouse epidermis results in differentiation of hair follicles into squamous epidermal cysts and formation of skin tumours. Development 129(1):95–109

Niemann C et al (2007) Dual role of inactivating Lef1 mutations in epidermis: tumor promotion and specification of tumor type. Cancer Res 67(7):2916–2921

Frye M et al (2003) Evidence that Myc activation depletes the epidermal stem cell compartment by modulating adhesive interactions with the local microenvironment. Development 130(12):2793–2808

Waikel RL et al (2001) Deregulated expression of c-Myc depletes epidermal stem cells. Nat Genet 28(2):165–168

Chiang MF et al (2013) Inducible deletion of the Blimp-1 gene in adult epidermis causes granulocyte-dominated chronic skin inflammation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(16):6476–6481

Kretzschmar K et al (2014) BLIMP1 is required for postnatal epidermal homeostasis but does not define a sebaceous gland progenitor under steady-state conditions. Stem Cell Rep 3(4):620–633

Horsley V et al (2006) Blimp1 defines a progenitor population that governs cellular input to the sebaceous gland. Cell 126(3):597–609

Nagarajan P et al (2009) Ets1 induces dysplastic changes when expressed in terminally-differentiating squamous epidermal cells. PLoS One 4(1):e4179

Blanpain C et al (2006) Canonical notch signaling functions as a commitment switch in the epidermal lineage. Genes Dev 20(21):3022–3035

Kurek D et al (2007) Transcriptome and phenotypic analysis reveals Gata3-dependent signalling pathways in murine hair follicles. Development 134(2):261–272

Hamanaka RB et al (2013) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote epidermal differentiation and hair follicle development. Sci Signal 6(261):ra8

Wang X et al (2008) AP-2 factors act in concert with Notch to orchestrate terminal differentiation in skin epidermis. J Cell Biol 183(1):37–48

Nguyen H, Rendl M, Fuchs E (2006) Tcf3 governs stem cell features and represses cell fate determination in skin. Cell 127(1):171–183

Kiso M et al (2009) The disruption of Sox21-mediated hair shaft cuticle differentiation causes cyclic alopecia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(23):9292–9297

Nowak JA et al (2008) Hair follicle stem cells are specified and function in early skin morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 3(1):33–43

Hertveldt V et al (2008) The development of several organs and appendages is impaired in mice lacking Sp6. Dev Dyn 237(4):883–892

Yang A et al (1999) p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398(6729):714–718

Romano RA et al (2012) DeltaNp63 knockout mice reveal its indispensable role as a master regulator of epithelial development and differentiation. Development 139(4):772–782

Oro AE, Higgins K (2003) Hair cycle regulation of Hedgehog signal reception. Dev Biol 255(2):238–248

Gu LH, Coulombe PA (2008) Hedgehog signaling, keratin 6 induction, and sebaceous gland morphogenesis: implications for pachyonychia congenita and related conditions. Am J Pathol 173(3):752–761

Nakamura Y et al (2003) Phospholipase Cdelta1 is required for skin stem cell lineage commitment. EMBO J 22(12):2981–2991

Binczek E et al (2007) Obesity resistance of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase-deficient (scd1−/−) mouse results from disruption of the epidermal lipid barrier and adaptive thermoregulation. Biol Chem 388(4):405–418

Sampath H et al (2009) Skin-specific deletion of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 alters skin lipid composition and protects mice from high fat diet-induced obesity. J Biol Chem 284(30):19961–19973

Miyazaki M, Man WC, Ntambi JM (2001) Targeted disruption of stearoyl-CoA desaturase1 gene in mice causes atrophy of sebaceous and Meibomian glands and depletion of wax esters in the eyelid. J Nutr 131(9):2260–2268

Georgel P et al (2005) A toll-like receptor 2-responsive lipid effector pathway protects mammals against skin infections with gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun 73(8):4512–4521

Fong LY et al (2000) Muir-Torre-like syndrome in Fhit-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97(9):4742–4747

Benavides F et al (1999) Nackt (nkt), a new hair loss mutation of the mouse with associated CD4 deficiency. Immunogenetics 49(5):413–419

Benavides F et al (2002) Impaired hair follicle morphogenesis and cycling with abnormal epidermal differentiation in nackt mice, a cathepsin L-deficient mutation. Am J Pathol 161(2):693–703

Peters F et al (2015) Ceramide synthase 4 regulates stem cell homeostasis and hair follicle cycling. J Invest Dermatol 135(6):1501–1509

Ebel P et al (2014) Ceramide synthase 4 deficiency in mice causes lipid alterations in sebum and results in alopecia. Biochem J 461(1):147–158

Robert K et al (2004) Hyperkeratosis in cystathionine beta synthase-deficient mice: an animal model of hyperhomocysteinemia. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 280(2):1072–1076

Chen HC et al (2002) Leptin modulates the effects of acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase deficiency on murine fur and sebaceous glands. J. Clin. Invest 109(2):175–181

Li J et al (2012) Progressive alopecia reveals decreasing stem cell activation probability during aging of mice with epidermal deletion of DNA methyltransferase 1. J. Invest Dermatol 132(12):2681–2690

Westerberg R et al (2004) Role for ELOVL3 and fatty acid chain length in development of hair and skin function. J Biol Chem 279(7):5621–5629

Coulson-Thomas VJ et al (2014) Heparan sulfate regulates hair follicle and sebaceous gland morphogenesis and homeostasis. J Biol Chem 289(36):25211–25226

Maier H et al (2011) Normal fur development and sebum production depends on fatty acid 2-hydroxylase expression in sebaceous glands. J Biol Chem 286(29):25922–25934

Essayem S et al (2006) Hair cycle and wound healing in mice with a keratinocyte-restricted deletion of FAK. Oncogene 25(7):1081–1089

Pan Y et al (2004) Gamma-secretase functions through Notch signaling to maintain skin appendages but is not required for their patterning or initial morphogenesis. Dev Cell 7(5):731–743

Grass DS et al (1996) Expression of human group II PLA2 in transgenic mice results in epidermal hyperplasia in the absence of inflammatory infiltrate. J Clin Invest 97(10):2233–2241

Sato H et al (2009) Group III secreted phospholipase A2 transgenic mice spontaneously develop inflammation. Biochem J 421(1):17–27

Schuhmacher AJ et al (2008) A mouse model for Costello syndrome reveals an Ang II-mediated hypertensive condition. J Clin Invest 118(6):2169–2179

White AC et al (2011) Defining the origins of Ras/p53-mediated squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(18):7425–7430

Lapouge G et al (2011) Identifying the cellular origin of squamous skin tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(18):7431–7436

Hughes MW et al (2014) Disrupted ectodermal organ morphogenesis in mice with a conditional histone deacetylase 1, 2 deletion in the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 134(1):24–32

Beaudoin GM 3rd et al (2005) Hairless triggers reactivation of hair growth by promoting Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(41):14653–14658

Driskell I et al (2012) The histone methyltransferase Setd8 acts in concert with c-Myc and is required to maintain skin. EMBO J 31(3):616–629

Megosh L et al (1995) Increased frequency of spontaneous skin tumors in transgenic mice which overexpress ornithine decarboxylase. Cancer Res 55(19):4205–4209

Soler AP et al (1996) Modulation of murine hair follicle function by alterations in ornithine decarboxylase activity. J Invest Dermatol 106(5):1108–1113

Perez CJ et al (2015) Increased susceptibility to skin carcinogenesis associated with a spontaneous mouse mutation in the palmitoyl transferase Zdhhc13 gene. J Invest Dermatol 135(12):3133–3143

Suzuki A et al (2003) Keratinocyte-specific Pten deficiency results in epidermal hyperplasia, accelerated hair follicle morphogenesis and tumor formation. Cancer Res 63(3):674–681

Mulherkar R et al (2003) Expression of enhancing factor/phospholipase A2 in skin results in abnormal epidermis and increased sensitivity to chemical carcinogenesis. Oncogene 22(13):1936–1944

Mill P et al (2009) Palmitoylation regulates epidermal homeostasis and hair follicle differentiation. PLoS Genet 5(11):e1000748

Niessen MT et al (2013) aPKClambda controls epidermal homeostasis and stem cell fate through regulation of division orientation. J Cell Biol

Castilho RM et al (2007) Requirement of Rac1 distinguishes follicular from interfollicular epithelial stem cells. Oncogene 26(35):5078–5085

Chrostek A et al (2006) Rac1 is crucial for hair follicle integrity but is not essential for maintenance of the epidermis. Mol Cell Biol 26(18):6957–6970

Benitah SA et al (2005) Stem cell depletion through epidermal deletion of Rac1. Science 309(5736):933–935

Kiguchi K et al (2000) Constitutive expression of erbB2 in epidermis of transgenic mice results in epidermal hyperproliferation and spontaneous skin tumor development. Oncogene 19(37):4243–4254

Ohta E et al (2009) Analysis of development of lesions in mice with serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) deficiency-Sptlc2 conditional knockout mice. Exp Anim 58(5):515–524

Ruzankina Y et al (2007) Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell 1(1):113–126

Urosevic J et al (2011) Constitutive activation of B-Raf in the mouse germ line provides a model for human cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(12):5015–5020

Tejera AM et al (2010) TPP1 is required for TERT recruitment, telomere elongation during nuclear reprogramming, and normal skin development in mice. Dev Cell 18(5):775–789

Lippens S et al (2011) Keratinocyte-specific ablation of the NF-kappaB regulatory protein A20 (TNFAIP3) reveals a role in the control of epidermal homeostasis. Cell Death Differ 18(12):1845–1853

Ilic D et al (1997) Skin abnormality in aged fyn−/− fak+/− mice. Carcinogenesis 18(8):1473–1476

Hammond NL, Headon DJ, Dixon MJ (2012) The cell cycle regulator protein 14-3-3sigma is essential for hair follicle integrity and epidermal homeostasis. J Invest Dermatol 132(6):1543–1553

Lee L et al (2007) Loss of the acyl-CoA binding protein (Acbp) results in fatty acid metabolism abnormalities in mouse hair and skin. J. Invest Dermatol 127(1):16–23

Jong MC et al (1998) Hyperlipidemia and cutaneous abnormalities in transgenic mice overexpressing human apolipoprotein C1. J Clin Invest 101(1):145–152

Mii S et al (2012) Epidermal hyperplasia and appendage abnormalities in mice lacking CD109. Am J Pathol 181(4):1180–1189

Zhang S et al (2014) Cidea control of lipid storage and secretion in mouse and human sebaceous glands. Mol Cell Biol 34(10):1827–1838

Leclerc EA et al (2009) Corneodesmosin gene ablation induces lethal skin-barrier disruption and hair-follicle degeneration related to desmosome dysfunction. J Cell Sci 122(Pt 15):2699–2709

Weber S et al (2011) The disintegrin/metalloproteinase Adam10 is essential for epidermal integrity and Notch-mediated signaling. Development 138(3):495–505

Mese G et al (2011) The Cx26-G45E mutation displays increased hemichannel activity in a mouse model of the lethal form of keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. Mol Biol Cell 22(24):4776–4786

Tanaka S et al (2007) A new Gsdma3 mutation affecting anagen phase of first hair cycle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 359(4):902–907

Sato H et al (1998) A new mutation Rim3 resembling Re(den) is mapped close to retinoic acid receptor alpha (Rara) gene on mouse chromosome 11. Mamm Genome 9(1):20–25

Porter RM et al (2002) Defolliculated (dfl): a dominant mouse mutation leading to poor sebaceous gland differentiation and total elimination of pelage follicles. J Invest Dermatol 119(1):32–37

Ruge F et al (2011) Delineating immune-mediated mechanisms underlying hair follicle destruction in the mouse mutant defolliculated. J. Invest Dermatol 131(3):572–579

Lunny DP et al (2005) Mutations in gasdermin 3 cause aberrant differentiation of the hair follicle and sebaceous gland. J. Invest Dermatol 124(3):615–621

Runkel F et al (2004) The dominant alopecia phenotypes Bareskin, Rex-denuded, and Reduced Coat 2 are caused by mutations in gasdermin 3. Genomics 84(5):824–835

Kumar S et al (2012) Gsdma 3(I359N) is a novel ENU-induced mutant mouse line for studying the function of Gasdermin A3 in the hair follicle and epidermis. J Dermatol Sci 67(3):190–192

Tarutani M et al (2012) GPHR-dependent functions of the Golgi apparatus are essential for the formation of lamellar granules and the skin barrier. J Invest Dermatol 132(8):2019–2025

Evers BM et al (2010) Hair growth defects in Insig-deficient mice caused by cholesterol precursor accumulation and reversed by simvastatin. J Invest Dermatol 130(5):1237–1248

Reichelt J et al (2004) Loss of keratin 10 is accompanied by increased sebocyte proliferation and differentiation. Eur J Cell Biol 83(11–12):747–759

Tanaka S et al (2007) Mutations in the helix termination motif of mouse type I IRS keratin genes impair the assembly of keratin intermediate filament. Genomics 90(6):703–711

Kikkawa Y et al (2003) A small deletion hotspot in the type II keratin gene mK6irs1/Krt2-6g on mouse chromosome 15, a candidate for causing the wavy hair of the caracul (Ca) mutation. Genetics 165(2):721–733

Lin MH, Hsu FF, Miner JH (2013) Requirement of fatty acid transport protein 4 for development, maturation, and function of sebaceous glands in a mouse model of ichthyosis prematurity syndrome. J Biol Chem 288(6):3964–3976

Owens P et al (2008) Smad4-dependent desmoglein-4 expression contributes to hair follicle integrity. Dev Biol 322(1):156–166

Yang L, Wang L, Yang X (2009) Disruption of Smad4 in mouse epidermis leads to depletion of follicle stem cells. Mol Biol Cell 20(3):882–890

Qiao W et al (2006) Hair follicle defects and squamous cell carcinoma formation in Smad4 conditional knockout mouse skin. Oncogene 25(2):207–217

Yang L et al (2005) Targeted disruption of Smad4 in mouse epidermis results in failure of hair follicle cycling and formation of skin tumors. Cancer Res 65(19):8671–8678

Han G et al (2006) Smad7-induced beta-catenin degradation alters epidermal appendage development. Dev Cell 11(3):301–312

Cao T et al (2007) Mutation in Mpzl3, a novel [corrected] gene encoding a predicted [corrected] adhesion protein, in the rough coat (rc) mice with severe skin and hair abnormalities. J Invest Dermatol 127(6):1375–1386

Mahajan MA et al (2004) The nuclear hormone receptor coactivator NRC is a pleiotropic modulator affecting growth, development, apoptosis, reproduction, and wound repair. Mol Cell Biol 24(11):4994–5004

McKenna T et al (2014) Embryonic expression of the common progeroid lamin A splice mutation arrests postnatal skin development. Aging Cell 13(2):292–302

Sagelius H et al (2008) Targeted transgenic expression of the mutation causing Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome leads to proliferative and degenerative epidermal disease. J Cell Sci 121(Pt 7):969–978

Odgren PR et al (2010) Disheveled hair and ear (Dhe), a spontaneous mouse Lmna mutation modeling human laminopathies. PLoS One 5(4):e9959

Mounkes LC et al (2003) A progeroid syndrome in mice is caused by defects in A-type lamins. Nature 423(6937):298–301

Sagelius H et al (2008) Reversible phenotype in a mouse model of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. J Med Genet 45(12):794–801

Viscomi C et al (2009) Early-onset liver mtDNA depletion and late-onset proteinuric nephropathy in Mpv17 knockout mice. Hum Mol Genet 18(1):12–26

Ruiz S et al (2003) Abnormal epidermal differentiation and impaired epithelial-mesenchymal tissue interactions in mice lacking the retinoblastoma relatives p107 and p130. Development 130(11):2341–2353

Xu X et al (2007) Co-factors of LIM domains (Clims/Ldb/Nli) regulate corneal homeostasis and maintenance of hair follicle stem cells. Dev Biol 312(2):484–500

Cui CY et al (2011) Shh is required for Tabby hair follicle development. Cell Cycle 10(19):3379–3386

Chiang C et al (1999) Essential role for sonic hedgehog during hair follicle morphogenesis. Dev Biol 205(1):1–9

Held WA et al (1989) T antigen expression and tumorigenesis in transgenic mice containing a mouse major urinary protein/SV40 T antigen hybrid gene. EMBO J 8(1):183–191

Martinez P et al (2009) Increased telomere fragility and fusions resulting from TRF1 deficiency lead to degenerative pathologies and increased cancer in mice. Genes Dev 23(17):2060–2075

Naito A et al (2002) TRAF6-deficient mice display hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99(13):8766–8771

Wood GA et al (2005) Two mouse mutations mapped to chromosome 11 with differing morphologies but similar progressive inflammatory alopecia. Exp Dermatol 14(5):373–379

Johnson KR et al (2003) Curly bare (cub), a new mouse mutation on chromosome 11 causing skin and hair abnormalities, and a modifier gene (mcub) on chromosome 5. Genomics 81(1):6–14

Mann SJ (1971) Hair loss and cyst formation in hairless and rhino mutant mice. Anat Rec 170(4):485–499

Sundberg JP et al (1997) Harlequin ichthyosis (ichq): a juvenile lethal mouse mutation with ichthyosiform dermatitis. Am J Pathol 151(1):293–310

Park YG et al (2001) Histological characteristics of the pelage skin of rough fur mice (C3H/HeJ-ruf/ruf). Exp Anim 50(2):179–182

Li SR et al (1999) Uncv (uncovered): a new mutation causing hairloss on mouse chromosome 11. Genet Res 73(3):233–238

Meng Q et al (2014) Eyelid closure in embryogenesis is required for ocular adnexa development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55(11):7652–7661

Vauclair S et al (2007) Corneal epithelial cell fate is maintained during repair by Notch1 signaling via the regulation of vitamin A metabolism. Dev Cell 13(2):242–253

Tsau C et al (2011) Barx2 and Fgf10 regulate ocular glands branching morphogenesis by controlling extracellular matrix remodeling. Development 138(15):3307–3317

Kenchegowda D et al (2011) Conditional disruption of mouse Klf5 results in defective eyelids with malformed Meibomian glands, abnormal cornea and loss of conjunctival goblet cells. Dev Biol 356(1):5–18

Schmidt-Ullrich R et al (2001) Requirement of NF-kappaB/Rel for the development of hair follicles and other epidermal appendices. Development 128(19):3843–3853

Chen Z et al (2014) FGF signaling activates a Sox9–Sox10 pathway for the formation and branching morphogenesis of mouse ocular glands. Development 141(13):2691–2701

Tukel T et al (2010) Homozygous nonsense mutations in TWIST2 cause Setleis syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 87(2):289–296

Yagyu H et al (2000) Absence of ACAT-1 attenuates atherosclerosis but causes dry eye and cutaneous xanthomatosis in mice with congenital hyperlipidemia. J Biol Chem 275(28):21324–21330

Ibrahim OM et al (2014) Oxidative stress induced age dependent Meibomian gland dysfunction in Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase-1 (Sod1) knockout mice. PLoS One 9(7):e99328

Lu Q et al (2011) 14-3-3sigma controls corneal epithelium homeostasis and wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52(5):2389–2396

Mauris J et al (2015) Loss of CD147 results in impaired epithelial cell differentiation and malformation of the Meibomian gland. Cell Death Dis 6:e1726

Parfitt GJ et al (2013) Absence of ductal hyper-keratinization in mouse age-related Meibomian gland dysfunction (ARMGD). Aging (Albany NY) 5(11):825–834

Falconer DS, Fraser AS, King JW (1951) The genetics and development of ‘crinkled’, a new mutant in the house mouse. J Genet 50(2):324–344

Jester JV, Rajagopalan S, Rodrigues M (1988) Meibomian gland changes in the rhino (hrrhhrrh) mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 29(7):1190–1194

Wang YC et al (2016) Meibomian gland absence related dry eye in ectodysplasin A mutant mice. Am J Pathol 186(1):32–42

Toonen J, Liang L, Sidjanin DJ (2012) Waved with open eyelids 2 (woe2) is a novel spontaneous mouse mutation in the protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 13 like (Ppp1r13l) gene. BMC Genet 13:76

Hassemer EL et al (2010) The waved with open eyelids (woe) locus is a hypomorphic mouse mutation in Adam17. Genetics 185(1):245–255

Wu S et al (2010) Disruption of the single copy gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor in mice by gene trap: severe reduction of reproductive organs and functions in developing and adult mice. Endocrinology 151(3):1142–1152

Lapatto R et al (2007) Kiss1−/− mice exhibit more variable hypogonadism than Gpr54−/− mice. Endocrinology 148(10):4927–4936

Seminara SB et al (2003) The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med 349(17):1614–1627

Funes S et al (2003) The KiSS-1 receptor GPR54 is essential for the development of the murine reproductive system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312(4):1357–1363

Novaira HJ et al (2014) Disrupted kisspeptin signaling in GnRH neurons leads to hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. Mol Endocrinol 28(2):225–238

Pearson HB, Phesse TJ, Clarke AR (2009) K-ras and Wnt signaling synergize to accelerate prostate tumorigenesis in the mouse. Cancer Res 69(1):94–101

Bierie B et al (2003) Activation of beta-catenin in prostate epithelium induces hyperplasias and squamous transdifferentiation. Oncogene 22(25):3875–3887

Good DJ et al (1997) Hypogonadism and obesity in mice with a targeted deletion of the Nhlh2 gene. Nat Genet 15(4):397–401

Cocquempot O et al (2009) Fork stalling and template switching as a mechanism for polyalanine tract expansion affecting the DYC mutant of HOXD13, a new murine model of synpolydactyly. Genetics 183(1):23–30

Molkentin JD et al (2000) Abnormalities of the genitourinary tract in female mice lacking GATA5. Mol Cell Biol 20(14):5256–5260

Halmekyto M et al (1991) Transgenic mice aberrantly expressing human ornithine decarboxylase gene. J Biol Chem 266(29):19746–19751

Sukseree S et al (2013) Targeted deletion of Atg5 reveals differential roles of autophagy in keratin K5-expressing epithelia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 430(2):689–694

Ahkter S et al (2005) Snm1-deficient mice exhibit accelerated tumorigenesis and susceptibility to infection. Mol Cell Biol 25(22):10071–10078

Tumiati M et al (2015) Loss of Rad51c accelerates tumourigenesis in sebaceous glands of Trp53-mutant mice. J Pathol 235(1):136–146

d’Anglemont de Tassigny X (2007) Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in mice lacking a functional Kiss1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(25):10714–10719

Yamada R et al (2003) Cell-autonomous involvement of Mab21l1 is essential for lens placode development. Development 130(9):1759–1770

Liu L et al (2004) Nucling mediates apoptosis by inhibiting expression of galectin-3 through interference with nuclear factor kappaB signalling. Biochem J 380(Pt 1):31–41

Sakai T et al (2010) Inflammatory disease and cancer with a decrease in Kupffer cell numbers in Nucling-knockout mice. Int J Cancer 126(5):1079–1094

Johnson LM, Sidman RL (1979) A reproductive endocrine profile in the diabetes (db) mutant mouse. Biol Reprod 20(3):552–559

Sweet HO et al (1996) Mesenchymal dysplasia: a recessive mutation on chromosome 13 of the mouse. J Hered 87(2):87–95

Govindarajan V et al (2000) Endogenous and ectopic gland induction by FGF-10. Dev Biol 225(1):188–200

Makarenkova HP et al (2000) FGF10 is an inducer and Pax6 a competence factor for lacrimal gland development. Development 127(12):2563–2572

Puk O et al (2009) A new Fgf10 mutation in the mouse leads to atrophy of the Harderian gland and slit-eye phenotype in heterozygotes: a novel model for dry-eye disease? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50(9):4311–4318

Iwamoto T et al (1990) Oncogenicity of the ret transforming gene in MMTV/ret transgenic mice. Oncogene 5(4):535–542

Lucchini F et al (1992) Early and multifocal tumors in breast, salivary, Harderian and epididymal tissues developed in MMTY-Neu transgenic mice. Cancer Lett 64(3):203–209

Mascrez B et al (2009) A transcriptionally silent RXRalpha supports early embryonic morphogenesis and heart development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(11):4272–4277

Lohnes D et al (1993) Function of retinoic acid receptor gamma in the mouse. Cell 73(4):643–658

Lohnes D et al (1994) Function of the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) during development (I). Craniofacial and skeletal abnormalities in RAR double mutants. Development 120(10):2723–2748

Grondona JM et al (1996) Retinal dysplasia and degeneration in RARbeta2/RARgamma2 compound mutant mice. Development 122(7):2173–2188

Gounari F et al (2002) Stabilization of beta-catenin induces lesions reminiscent of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, but terminal squamous transdifferentiation of other secretory epithelia. Oncogene 21(26):4099–4107

Steingrimsson E et al (1996) The semidominant Mi(b) mutation identifies a role for the HLH domain in DNA binding in addition to its role in protein dimerization. EMBO J 15(22):6280–6289

Dupe V et al (2003) A newborn lethal defect due to inactivation of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 3 is prevented by maternal retinoic acid treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100(24):14036–14041

Tamaoki N (2001) The rasH2 transgenic mouse: nature of the model and mechanistic studies on tumorigenesis. Toxicol Pathol 29(Suppl):81–89

Saitoh A et al (1990) Most tumors in transgenic mice with human c-Ha-ras gene contained somatically activated transgenes. Oncogene 5(8):1195–1200

Guerra C et al (2003) Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer Cell 4(2):111–120

Coto-Montes A et al (1997) Histopathological features of the Harderian glands in transgenic mice carrying MMTV/N-ras protooncogene. Microsc Res Tech 38(3):311–314

Mangues R et al (1990) Tumorigenesis and male sterility in transgenic mice expressing a MMTV/N-ras oncogene. Oncogene 5(10):1491–1497

Heath LA et al (1992) Harderian gland hyperplasia in c-mos transgenic mice. Int J Cancer 51(2):310–314

Matt N et al (2005) Retinoic acid-dependent eye morphogenesis is orchestrated by neural crest cells. Development 132(21):4789–4800

Schild A et al (2006) Impaired development of the Harderian gland in mutant protein phosphatase 2A transgenic mice. Mech Dev 123(5):362–371

Valleix S et al (1999) Expression of human F8B, a gene nested within the coagulation factor VIII gene, produces multiple eye defects and developmental alterations in chimeric and transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 8(7):1291–1301

Jhappan C et al (1992) Expression of an activated Notch-related int-3 transgene interferes with cell differentiation and induces neoplastic transformation in mammary and salivary glands. Genes Dev 6(3):345–355

Reed SM et al (2014) NIAM-deficient mice are predisposed to the development of proliferative lesions including B-cell lymphomas. PLoS One 9(11):e112126

Sinn E et al (1987) Coexpression of MMTV/v-Ha-ras and MMTV/c-myc genes in transgenic mice: synergistic action of oncogenes in vivo. Cell 49(4):465–475

White V, Sinn E, Albert DM (1990) Harderian gland pathology in transgenic mice carrying the MMTV/v-Ha-ras gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 31(3):577–581

Tremblay PJ et al (1989) Transgenic mice carrying the mouse mammary tumor virus ras fusion gene: distinct effects in various tissues. Mol Cell Biol 9(2):854–859

Adnane J et al (2000) Loss of p21WAF1/CIP1 accelerates Ras oncogenesis in a transgenic/knockout mammary cancer model. Oncogene 19(47):5338–5347

Gruneberg H (1971) Exocrine glands and the Chievitz organ of some mouse mutants. J Embryol Exp Morphol 25(2):247–261

Truslove GM (1962) A gene causing ocular retardation in the mouse. J Embryol Exp Morphol 10:652–660

Parnell PG et al (2005) Frequent Harderian gland adenocarcinomas in inbred white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus). Comput Med 55(4):382–386

Acknowledgments

Sebaceous gland-related research has been supported by grants from the DFG to MRS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ehrmann, C., Schneider, M.R. Genetically modified laboratory mice with sebaceous glands abnormalities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 4623–4642 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2312-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2312-0