Abstract

Achieving gender equality and empowerment has been a global goal for many years and since 2015 has been the focus of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well. Given the challenges in reducing gender inequality, there was a global consensus that national budgets should specifically focus on gender. Australia was the first country to initiate gender budgeting or gender-responsive budgeting (GRB) and presented a Women’s Budget Statement at a meeting of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Working Party on Women and the Economy in February 1985.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Achieving gender equality and empowerment has been a global goal for many years and since 2015 has been the focus of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well. Given the challenges in reducing gender inequality, there was a global consensus that national budgets should specifically focus on gender. Australia was the first country to initiate gender budgeting or gender-responsive budgeting (GRB) and presented a Women’s Budget Statement at a meeting of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Working Party on Women and the Economy in February 1985 (Sharp & Broomhill, 2014). Initiatives were begun in other countries as well, and GRB was first discussed at a global level at the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995 in Beijing, China (Stotsky, 2016), attended by representatives from 189 countries, which gave the movement further impetus. Countries agreed to look at their national budgets through a gendered lens and integrate a gender perspective in their budgetary policies (UN Women, 1995).

The Council of Europe in 2005, defined gender budgeting as a ‘gender-based assessment of budgets incorporating a gender perspective at all levels of the budgetary process and restructuring revenues and expenditures in order to promote gender equality’ (Council of Europe, 2005). However, while the movement started with a somewhat narrow focus on bridging the gap between men and women, it was subsequently expanded to include the needs of all people. OECD in 2016 defined it as ‘integrating a clear gender perspective within the overall context of the budgetary process through special processes and analytical tools, with a view to promoting gender-responsive policies’ (Downes et al., 2017). A 2016 IMF paper defined it as ‘an approach to budgeting that uses fiscal policy and administration to promote gender equality, and girls’ and women’s development’ (Stotsky, 2016).

Approaches towards GRB differed and continuously evolved across countries in the framework adopted, mainly because of the diverse ways in which gender inequalities manifested themselves in different settings. Emerging economies faced different challenges compared to high-income economies, with larger informal economic sectors that typically employed a larger proportion of women, weaker political accountability, and larger gender gaps in terms of education and access to health services. It has been observed that gender budgeting is closely interlinked with economic development in emerging economies (Nolte et al., 2021).

Though the approaches for different countries have certainly been heterogeneous and diverse, there are certain common essential components that go into a GRB, irrespective of the setting. The most important element is of course the collection and analysis of gender-disaggregated data for a variety of indicators; without such data, GRBs cannot be meaningful. The other elements are the involvement of multiple stakeholders in recognizing and identifying gender-based needs assessment; all levels of government including the parliament, policymakers and managers, civil society organizations, especially women’s groups and researchers, need to collectively be able to push the agenda on GRB. Finally, robust tracking alongside sound monitoring and evaluating systems are required to assess implementation gaps and progress. The last is critical because a truly gender-responsive budget should be able to track how funds are being raised, allocated, and spent. Such information is critical to help make government spending more efficient and effective. These are the minimum requirements of a sound system of GRB, and such a system will lend flexibility to the tool, which is important for adapting and adjusting to a dynamic situation.

Approaches, and tools, for gender-responsive budgeting are varied—they can be adapted for specific and national contexts. No particular approach for GRB has been described as standard or ideal; what works in one country context may not necessarily work in another and as a result, different countries have seen various levels of success in their approaches. Diane Elson developed a set of analytical tools in 1995 that helps bring in a gender perspective at all levels of decision-making, and other tools have been developed in the following years based on work from Budlender, Sharp, and Elson (Elson, 1999). Tools may be used separately or in combination, according to the country’s situation as well as the particular approach being followed.

One way of classifying tools is by the stage of the budgetary process they may be applied in, as discussed in the OECD typology (Downes et al., 2017), which mentions mainly three types of approaches; ex ante budgeting, concurrent budgeting, and ex post budgeting. The ex ante approach does the analysis in advance of inclusion in the budget, does a baseline analysis, and uses a needs-assessment exercise which is mostly qualitative. Belgium and Japan are two examples of this approach. The concurrent GRB approach is one where requirements for a minimum pre-specified allocation linked to GRB policies are mandated and some form of gender-related budget incidence analysis is undertaken to assess the overall impact. India is a good example of concurrent GRB. Finally, the ex post approach is mainly based on a post-allocation audit of spending to determine the extent to which gender equality objectives are being attained through the policies detailed in the annual budget. Sweden, the Netherlands, and Norway undertake ex post gender audits as part of their budgeting process.

There has been growing interest globally in linking GRB processes with broader public finance management or PFM reforms and in institutionalizing gender-responsive PFM reforms (Anwar et al., 2016). A fully implemented gender-responsive budget that tracks allocations of funds and their implications on gender equality outcomes, can represent an advanced form of PFM reform (Kovsted, 2010). However, in practice, most existing GRB initiatives are simpler analyses of allocations within sectors.

Though there is an abundance of literature on the definition, implementation, and justification of gender budgeting, there are far fewer resources for measuring its performance and impact. Many countries have not formally adopted a nationwide GRB approach; however, informal and fragmented applications of the process have been undertaken by governments as well as non-government agencies and these frequently are not taken into account when it comes to documenting and assessing the real-world impacts of gender budgeting. Further, there has been limited application of a gender perspective in spending review even in developed countries. A small collection of quantitative papers has measured the impact of gender budgeting through labour force participation (Chakraborty et al., 2018), school enrolment (Stotsky & Zaman, 2016), and macro-aggregates like growth (Chakraborty et al., 2019). The results have allowed researchers to conclude that gender budgeting has had an undeniable impact on the increased representation of women in decision-making processes, better labour market conditions, education and employment for women, and financial independence for women as primary bank account holders. It has also helped in the inclusion of transgenders as potential beneficiaries for receiving direct benefit transfers under social schemes, with explicit mention of schemes earmarked for the third gender across many Indian states (Nair & Moolakkattu, 2018).

One area that has sparse literature is the impact of GRB on health outcomes. Given the stark inequalities in health outcomes across genders requiring policy focus, an important question to raise is whether GRBs have helped reduce such inequalities over the years.

A 2019 study (Heymann et al., 2019) reviewed existing literature on programmes that aimed to reduce gender inequality and improve health. The results indicated that improved equality in education and at work, in the form of policies such as tuition-free primary education and paid maternity and parental leave policies, have had a positive impact on health outcomes. The study also found that greater gender balance in governance and decision-making roles made it easier for such policies to be introduced and successfully implemented. The study concluded that for sustainable change to the status quo and quantifiable improvements in health outcomes, programmes should be multi-sectoral, have a multi-level approach, work in a bottom-up manner, and extend beyond the health sector.

Another scoping review (Crespí-Lloréns et al., 2021) looked at identifying and analysing policies aimed at reducing gender inequalities in health between 2002 and 2018 and found that very few policies have been formulated, implemented, or evaluated to address this problem. The review found that though the number of studies about tackling gender inequalities in health had increased in recent years, these had not all, however, been successful. The reasons ranged from flawed study designs and implementation processes to the lack of availability of accurate sex-disaggregated data and gender inequality indexes. Interventions were also found to be under-financed, plagued by bureaucratic issues, lacked adequate women’s participation in decision-making, and were difficult to implement.

In this background of increasing focus on GRB and lack of sufficient evidence on the impact of GRBs on health outcomes, this paper explores whether selected major health outcomes improved in countries that introduced gender budgets and whether countries that adopted GRB and did not adopt GRB had different paths of improvements over the years.

The main concern in adopting a quantitative approach to measuring the impact of GRB on health outcomes is the lack of uniformity in approaches. Since countries incorporated GRB in a variety of ways, over different time periods, and made incremental course corrections, a straightforward quantitative approach with GRB as a simple explanatory variable can yield misleading results. The differences could be attributed to the approach, the methods, and the range of services where GRB was introduced, rather than whether or not the countries had a GRB.

The other problem is that most countries globally have adopted some or the other form of GRB, making it difficult to get enough data on countries that have not. Data is also not readily available on whether health sector budgets in all countries have followed a GRB format, though one can assume that health being a key sector, any adoption of GRB would be implemented in the health sector as well.

Instead, we try and piece together evidence from a variety of sources on how countries did on health after the adoption of GRB, to what extent inequalities could be brought down, compare trajectories of change in key health outcomes for countries that did adopt and the few countries that did not and offer possible explanations on what could explain the observed patterns. We take a closer look at India and attempt to understand whether its adoption of GRB made a substantial impact on health inequalities. Finally, we look at other possible factors that might have impacted gender inequalities in the health sector and could be prioritized over gender budgets.

2 Gender Inequality, Gender Gaps, and Health Outcomes

Given the problem of attribution and diversity of approaches in GRB, it is not entirely clear how exactly to assess the impact of GRB on health outcomes.

We look at four indicators to explore possible impact. Gender inequality as gleaned from available global data, Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), all-cause mortality ratio for males and females, and treatment-seeking behaviour by gender. Since most countries have implemented ministry-wise gender budgets, health ministries, and departments—it can be assumed—would also have addressed gender gaps in their allocations. Also, improvements on other human development fronts via GRB would also indirectly impact health outcomes.

2.1 Gender Inequality and Gender Budgets

UNDP’s Gender Inequality Index (GII) (UNDP, 2020) measures gender inequalities in three aspects of human development: reproductive health (measured by MMR and adolescent birth rates); empowerment (measured by proportion of parliamentary seats occupied by women and proportion of men and women with higher education); and economic status (measured by labor force participation rate of men and women). The higher the GII value, the more disparities between females and males, and the more loss to human development. Figure 1 depicts GII values across human development groups and Fig. 2 depicts GII values across regions, for the year 2019. It shows that the level of human development is negatively related to GII; lower is human development, higher is GII. Figure 2 shows GII across regions and indicates that developed countries tend to have lower gender inequalities. Whatever the mechanisms, progress in human development would ensure reduction in gender disparities.

The Global Gender Gap Index (GGI) published by the World Economic Forum (WEF) ranks over 150 countries on the current status of gender-based gaps in four key domains—Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment—and tracks their progress in closing these gaps in an annually published report (WEF, 2021). Table 1 depicts the top ten ranked countries according to this index, along with whether or not these countries have undertaken any GRB efforts.

As can be seen, not all the countries among the top ten ranks have undertaken gender budgeting, though four of the top five have. Similarly, for the bottom ten countries that have yet to close the gender gaps, many countries, including India, have undertaken GRB processes, indicating the possibility of GRBs being neither necessary nor sufficient for bringing about greater gender equality.

2.2 Maternal Mortality Ratio

While the MMR only pertains to women, GRBs would require investments in the prevention of maternal mortality by allocating sufficient resources to a variety of interventions. Changes in MMR, therefore, would reflect changes in policies and investments in reproductive health.

Table 2 gives the MMR and also adolescent birth rate—another indicator which needs focus in the health sector—for countries with different levels of human development.

The first thing to note is that both MMR and adolescent birth rates are worse for countries with lower levels of human development. For the low human development countries, MMR is 40 times higher compared to countries with very high human development. This straightaway indicates that countries with better human development would be able to achieve better outcomes in any case. This could also be due to better allocations to health, with or without gender budgets. While many factors go into adverse health outcomes, from a policy perspective, one key tool is health financing, a point to which we return later in the paper.

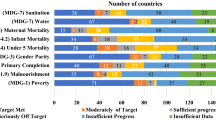

MMR for several countries over the period 1990–2017 has been plotted in Fig. 3 to see the trends and patterns. Figures 3a, b depict the MMR trends in high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries, respectively. The years mentioned denote the year during which GRB processes were started in the country; no year mentioned indicates that the country has not undertaken any GRB exercises.

For the richer countries, MMR was already very low, so the introduction of GRB did not make much of a difference. For countries like Cuba and Denmark, that had somewhat higher MMR around the 1990s, the fall started quite soon. While Cuba does not have a GRB, Denmark introduced GRB in 2000, but MMR started falling after 1995 in any case.

A similar story can be seen for low- and middle-income countries as well. There is a noticeable fall in MMR before the implementation of GRB in countries like Ethiopia and Bangladesh. In some other countries, the downward trend is visible despite a lack of introduction of GRB.

2.3 All-Cause Mortality Rates by Gender

Male–female differences in mortality rates are governed by complex factors ranging from epidemiology to social and cultural factors that impact behaviour (Crimmins et al., 2019). There remains a gap between male and female all-cause mortality, with males having higher death rates than females. In relatively high mortality settings, there is scope to reduce the rates for both the genders, and in fact, bring down male mortality faster with better allocations to prevention of non-communicable diseases and other lifestyle behaviour interventions. We look at all-cause mortality rates for males and females for selected countries in the low-middle-income categories, including India. While we cannot predict without knowing the design of policy under GRB which way the narrowing will go—whether male or female or both rates would come down—any difference might give us proof of some impact from GRB.

Figure 4 shows the trends for mortality rates for 1000 persons from 1990 to 2018 for four countries with high mortality compared to developed countries—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Uganda. The dotted line in each graph indicates the year when GRB was started in the country. As can be seen, overall mortality rates are decreasing over the years, and the declines started before the introduction of GRB in each of these countries. There is a secular decline in male and female mortality, but not sharp enough and the gaps have not changed over the years in any perceptible way.

How do these countries look when compared to trends in all-cause mortality for males and females in countries that have not undertaken GRB?

Figure 5 shows the trends for mortality rates for 1000 persons from 1990 to 2018 for four selected countries which have not adopted GRB measures yet—Nigeria, Congo, Burundi, and Iran. All these countries also have high mortality rates. As can be seen, all the four countries have managed to lower mortality rates, even in the absence of GRB, and certain countries, such as Iran have also managed to narrow the gender gap.

These pieces of evidence seem to indicate that GRB has not mattered much for changing major health outcomes across countries.

2.4 Treatment-Seeking Behaviour and Out-Of-Pocket Spending

It is much less easy to identify whether out-of-pocket spending (OOPS) has a gendered angle to it, given that much of the data remains at the household level and is at times difficult to attribute to different family members. However, there is adequate evidence that women are especially disadvantaged seeking care compared to men and some evidence of their relatively higher OOPS.

In a sample of 65 developing countries, cost was identified as a key factor that affected women’s ability to access care (UN Women, 2018). When women lack financial autonomy, they are forced to rely on men to meet their transport needs as well as treatment costs. In low-income settings, women may have to resort to informal healthcare providers and low-cost medicines, whereas men spend a greater share of resources on their own health needs. This has been observed especially in more low- and middle-income patriarchal cultures such as in Bangladesh (Pike et al., 2021) and Uganda (Morgan et al., 2017). Men, mothers-in-law, or older family members are often gatekeepers for women’s access to health care, and a husband’s consent for the provision of treatment is often required by health providers and is even mandated by law in certain countries. Further, women incur more out-of-pocket payments than men. This is because out-of-pocket expenditure for delivery care and other reproductive health services places a higher financial burden on women, and this also adversely impacts women’s utilization of essential services.

A study analysing the differences in out-of-pocket and total healthcare expenditures among adults with diabetes in the US found that women with diabetes had significantly higher expenditures compared to men, particularly for healthcare services including office visits, home-based care, and prescriptions (Williams et al., 2017). Earlier studies have also found that women with diabetes tend to have higher estimated annual medical spending and additional lifetime incremental expenses compared to men with diabetes (Zhuo et al., 2014).

A recent WHO-PAHO (Pan-American Health Organization) report compiled evidence that indicated that women’s OOPS is systematically higher than that of men (PAHO, 2021).

The evidence on OOPS is closely related to health coverage and health expenditures in countries. Evidence from both high- (e.g. the USA) and middle-income countries (e.g. South Africa) with significant private health insurance coverage indicates that private health insurance is inequitable because it excludes those who are unemployed and socio-economically disadvantaged. A study of privately insured households in South Africa found that less than half of privately insured households were only partially insured, and on average, household heads in partially insured households were more often found to be female, unmarried, with primary school education or no education, Black and unemployed (Govender et al., 2014).

In India, household members within male-headed households were twice as likely to be insured as those in female-headed households (Witter et al., 2017), and this has implications for healthcare access as well. There are voluntary, community-based health insurance schemes which aim to close the gap in insurance coverage through low premiums. These schemes target women, along with poor and rural populations, however, they have also been unable to provide coverage for those without access to cash.

In contrast, women’s increased decision-making autonomy and access to economic resources are positively associated with their use of healthcare services in many sub-Saharan African countries (Lee et al., 2017). Similarly, a study from Pakistan found that a 1% increase in women’s decision-making power was correlated with a nearly 10% increase in their use of maternal health services (Heise et al., 2019). Another study on the effect of health expenditure on health outcomes for the period 2000–2015 for 177 countries found a significant positive relationship between health expenditure and infant mortality rate, and maternal mortality ratio for the study period across 11 quantiles, with the most impact observed in developing economies (Owusu et al., 2021).

A study on the association between medical spending and health status across eight African countries also had similar findings—increase in public healthcare spending is expected to lead to a reduction in female mortality, male mortality, number of maternal deaths, incidence of tuberculosis, and prevalence of HIV (Bein, 2020).

The last set of evidence on treatment-seeking behaviour and health coverage points towards health financing as a key policy knob for improving health outcomes in countries, with concomitant spread of UHC.

3 Gender Budgeting in India

In India, the first gender-focused analysis of economic policy issues was done by the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) in 2002 (Chakraborty, 2013). The report analysed the Union Budget from a gendered perspective, following which in 2003, the Indian government asked each ministry and department to include a section on gender issues in their respective annual reports. In 2004, the Ministry of Finance instructed all ministries to establish GRB Cells. From here on, all ministries were expected to include a note in the budget circulars that would reflect gender allocations in two categories; Part A: schemes that were targeted towards women with 100% of the budget allocation and Part B schemes where at least 30% of the budget was allocated for women (Ministry of Women and Child Development).

In 2005–06, the first Gender Budget Statement (GRBS) included ten demands for grants. Each one was presented by a particular ministry and included a statement of the total provision of funds required for a given service along with a statement of the detailed estimate of the grant divided into line items. In addition to departments and ministries, some states also incorporated GRB into their budget planning.

GRB efforts in the country have continued since then, as the Indian government was cognizant of the need for programmes and policies on gender equality and had made efforts over the years to make budgets gender-responsive, including setting up of a separate ministry that could further facilitate gender-focused policymaking in the country.

In order to analyse whether these efforts have translated into better outcomes, we use the GGI to track India’s progress in reducing gender gaps, since the index is inclusive of a number of indicators. As of 2020, India is ranked 112th globally on the GGI and 4th within the South Asian region. Other countries in the region, such as Bangladesh, have achieved better gender parity. The 2021 rankings are worse as the COVID-19 pandemic amplified the pre-existing gender gaps leading to the gaps being asymmetrically intensified between men and women. In 2021, India ranked 140 out of 156 countries with a score of 0.625, falling by 28 ranks compared to 2020. The economic gender gap runs particularly deep in India with only 35% of the gap having been bridged in this area, and since 2006, the gap has significantly widened. India is the only country where the economic gender gap is larger than the political gender gap.

Figure 6 plots the scores of India on five parameters as per the GGI Reports from 2006 to 2021. India has the most gender gap in the domain of health and survival, followed by educational attainment. It does the best in political empowerment of women.

As the graph indicates, despite an early start and continued gender budgeting efforts in the country, not much has changed over the years for any of the indicators, including health and survival. There has been some slight improvement in the economic participation and opportunity indicator, however.

Numerous experts have analysed India’s GRB processes to understand why the efforts have not resulted in better outcomes. One possible explanation is the nature of the main tool in use—the Gender Budget Statement. The GRBS essentially brings out the percentage of the total expenditure of the budget that flows to women and is the main feature of India’s GRB process. Like with any tool that requires accurate classification, the GRBS has also faltered in categorizing items accurately. For instance, schemes under Part A and B were cross-classified and some schemes were excluded because they did not mention specific coverage for women. Further, for schemes categorized in Part B of the statement, it was not always evident what methodology was used to estimate the percentage of funds allocated to women (Mishra & Sinha, 2012). In any case, the rationale of allocation for various categories in Part B has not been clearly stated anywhere. Also, ministries that are considered gender-neutral did not have proper guidance on how to apportion their budgets (Mehta, 2020).

Even if these challenges are rectified, the GRBS might work well as an accounting tool and enable a good understanding of changing allocations across interventions over time. But merely an accounting tool to analyse allocations is not helpful unless backed by ex ante gender-disaggregated data. Without a thorough understanding of what is required, what has been spent, and what has been achieved, the process seems like a routine exercise of fulfillment of a reporting obligation rather than a well-thought-out planning exercise.

There are some areas where GRB processes have probably played a part in improving outcomes—for example, in education and labor market under the National Rural Employment Scheme (MGNREGA). However, there still remain significant inequalities in terms of health outcomes.

4 Gender Budgets or Health Allocations?

Countries that have made good progress on health outcomes and inequalities are mainly countries that have been able to increase their health spending and expand universal health care (UHC), with or without GRB.

Developed countries undertaking gender budgeting mostly focus on specific issues pertaining to inequalities in political participation, labor market, salaries, tax burden, leave rules, etc. These countries do not require to focus specifically on health because they have already achieved significant improvements in health indicators.

For developing countries, the issues are much more complex, ranging from prevention and eradication of diseases and universal immunization to more complex areas of NCD and triple burden of diseases including new and emerging pathogens. At the same time, countries require significant health systems strengthening, especially of public health services. Countries without UHC are mostly in the low development–low health financing space with adverse health outcomes. The primary focus for these countries should be to raise resources for health and UHC. As seen in the preceding section, UHC—achieved via significant investment in the health sector—is one significant way of reducing gender inequalities in access and outcomes.

Figure 7 plots the GII (which includes health and survival sub-index) against domestic general government health expenditure in GDP and shows that there is a negative relationship between the two: higher is government expenditure in GDP, lower is GII indicating more equality between sexes.

For fast-tracking improvements in health outcomes like MMR (Fig. 8), the key policy knob remains health expenditures; as the figure shows, there is a strong negative relationship between government health expenditure and MMR, and higher health spending by government would ultimately help reduce gender gaps in health outcomes, if the investments are being made sensibly.

For health investments to be gender-sensitive in a GRB approach, it is important to collect granular data on a number of indicators that would help policymakers narrow in on the key gender gaps in health. While a number of studies indicate that women are especially disadvantaged, truly gender-responsive analyses would need to focus on both the genders. For example, a systematic review finds that being unmarried put men at higher risk of stroke and all-cause mortality compared to women (Wang et al., 2020). It further reported that divorced/separated men had a higher risk of cancer mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality. Similarly, many studies exist that find that among patients with COVID-19 infection, men had a significantly higher mortality than women; one study using a multinational database had a similar finding and further reported that this difference could not be explained fully by the higher prevalence of comorbidities in men (Alkhouli et al., 2020). A study on European countries indicates that musculo-skeletel pain was higher among women compared to men (US-based study found that men were twice as likely as women to die during the first and second years after hip fracture (Cimas et al., 2018). A study from Italy found that lower cardiovascular risk profile may reduce all-cause and CVD mortality in older people, and the benefits are stronger and longer in women (Trevisan et al., 2021).

These examples show that such granular gender-based data are the only way to understand where the gender gaps are and how these might be bridged. However, it also indicates the difficulty that countries would have to collect such nuanced data. Most developing countries and many developed countries as well are not currently equipped to collect this kind of detailed data required for gender budgets. A routine budget allocation model cannot serve the dynamic and fluid scenario around gender equality, for which one requires a different gender planning exercise. Redistributing meagre health expenditure to fulfil gender budget obligations in the departments and ministries of health may be counterproductive and give a false sense of achievement.

5 Conclusion

While gender budgeting has resulted in special attention being given to health outcomes in countries such as Brazil, Japan, and Mexico, for other developing countries that still have adverse health indicators, outcomes may respond better to higher health allocations rather than allocation of meagre funds to separate gender. Expansion of a well-defined UHC agenda would in any case ensure greater gender equality in access and outcomes, and the only way to expand UHC is through higher health allocations by governments, with the concomitant reduction in OOPS.

In any case, in the absence of clear objectives of GRB in health, proper needs assessment, availability of gender-disaggregated data, and sound post-implementation evaluation, a GRB exercise can become a mechanical one, to meet administrative requirements. It can also become counter-productive if it gives an illusion that GRB would lead to improvements in outcomes. It might be better for governments and development agencies to emphasize gender-responsive budgeting in fewer targeted areas such as labour markets, political empowerment, and specific programmes targeting genders, instead of forcing all allocations to follow GRB guidelines. For health, the best step forward to address gender inequality would remain investment in health and adequate levels of health financing to further the UHC agenda. UHC—if designed with evidence—would address existing inequalities across genders, and may not need additional focus on GRB. For the health sector, therefore, GRB is neither necessary nor sufficient to address gender inequalities.

References

Alkhouli, M., Nanjundappa, A., Annie, F., Bates, M. C., & Bhatt, D. L. (2020). Sex differences in case fatality rate of COVID-19: insights from a multinational registry. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 95, No. 8, pp. 1613–1620). Elsevier.

Anwar, S., Downs, A., & Davidson, E. (2016). How can PFM reforms contribute to gender equality outcomes? UN Women and DFID Working Paper.

Bein, M. (2020). The association between medical spending and health status: A study of selected African countries. Malawi Medical Journal, 32(1), 37–44.

Chakraborty, L. (2013). A case study of gender responsive budgeting in India (pp. 1–13). Res Report Common wealth Publication.

Chakraborty, L., Ingrams, M., & Singh, Y. (2018). Fiscal policy effectiveness and inequality: Efficacy of gender budgeting in Asia Pacific (No. 18/224).

Chakraborty, L., Ingrams, M., & Singh, Y. (2019). Macroeconomic policy effectiveness and inequality: Efficacy of gender budgeting in Asia Pacific (Vol. 920). Levy Economics Institute, Working Papers Series.

Cimas, M., Ayala, A., Sanz, B., Agulló-Tomás, M. S., Escobar, A., & Forjaz, M. J. (2018). Chronic musculoskeletal pain in European older adults: Cross-national and gender differences. European Journal of Pain, 22(2), 333–345.

Council of Europe. (2005). Council of europe final report of group of specialists on gender budgeting. Directorate of Human Rights.

Crespí-Lloréns, N., Hernández-Aguado, I., & Chilet-Rosell, E. (2021). Have policies tackled gender inequalities in health? A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 327.

Crimmins, E. M., Shim, H., Zhang, Y. S., & Kim, J. K. (2019). Differences between men and women in mortality and the health dimensions of the morbidity process. Clinical Chemistry, 65(1), 135–145.

Downes, R., Von Trapp, L., & Nicol, S. (2017). Gender budgeting in OECD countries. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 16(3), 71–107.

Elson, D. (1999). Tools for GRB. Commonwealth Secretariat.

Govender, V., Ataguba, J. E., & Alaba, O. A. (2014). Health insurance coverage within households: The case of private health insurance in South Africa. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice, 39(4), 712–726.

Heise, L., Greene, M. E., Opper, N., Stavropoulou, M., Harper, C., Nascimento, M., ... & Gupta, G. R. (2019). Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. The Lancet, 393(10189), 2440–2454.

Heymann, J., Levy, J. K., Bose, B., Ríos-Salas, V., Mekonen, Y., Swaminathan, H., ... & Gupta, G. R. (2019). Improving health with programmatic, legal, and policy approaches to reduce gender inequality and change restrictive gender norms. The Lancet, 393(10190), 2522–2534.

Kovsted, J. A. (2010). Integrating gender equality dimensions into public financial management reforms. Gender Equality, Women’s Empowerment and the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Issues Brief 6: OECD.

Lee, R., Kumar, J., & Al-Nimr, A. (2017). Women’s healthcare decision-making autonomy by wealth quintile from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in sub-Saharan African countries. International Journal of Womens Health Wellness, 3(054), 2474.

Mehta, A. K. (2020). Union budget 2020–21: A critical analysis from the gender perspective. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(16).

Mishra, Y., & Sinha, N. (2012). Gender responsive budgeting in India: What has gone wrong? Economic and Political Weekly, 47(17).

Morgan, R., Tetui, M., Muhumuza Kananura, R., Ekirapa-Kiracho, E., & George, A. S. (2017). Gender dynamics affecting maternal health and health care access and use in Uganda. Health Policy and Planning, 32(suppl_5), v13–v21.

Nair, N. V., & Moolakkattu, J. S. (2018). Gender-responsive budgeting: The case of a rural local body in Kerala. SAGE Open, 8(1), 2158244017751572.

Nolte, I. M., Polzer, T., & Seiwald, J. (2021). Gender budgeting in emerging economies–a systematic literature review and research agenda. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies.

Owusu, P. A., Sarkodie, S. A., & Pedersen, P. A. (2021). Relationship between mortality and health care expenditure: Sustainable assessment of health care system. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0247413.

Pan American Health Organization. (2021). Out-of-pocket expenditure: The need for a gender analysis. Pan American Health Organization.

Pike, V., Kaplan Ramage, A., Bhardwaj, A., Busch-Hallen, J., & Roche, M. L. (2021). Family influences on health and nutrition practices of pregnant adolescents in Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 17, e13159.

Sharp, R., & Broomhill, R. (2014). A case study of gender responsive budgeting in Australia. Commonwealth Secretariat.

Stotsky, M. J. G. (2016). Gender budgeting: Fiscal context and current outcomes. IMF working papers: 1–50. International Monetary Fund.

Stotsky, M. J. G., & Zaman, M. A. (2016). The influence of gender budgeting in Indian states on gender inequality and fiscal spending. International Monetary Fund.

Trevisan, C., Capodaglio, G., Ferroni, E., Fedeli, U., Noale, M., Baggio, G., ... & Sergi, G. (2021). Cardiovascular risk profiles and 20-year mortality in older people: gender differences in the Pro.V.A. study. European Journal of Ageing, 19(1), 37–47.

United Nations Development Programme. (2020). Human development report 2020: The next frontier—Human development and the anthropocene. United Nations Development Programme.

UN Women. (1995). Beijing declaration and platform for action: Beijing+5 political declaration and outcome.

UN Women. (2018). Turning promises into action: Gender equality in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations Women.

Wang, Y., Jiao, Y., Nie, J., O’Neil, A., Huang, W., Zhang, L., ... & Woodward, M. (2020). Sex differences in the association between marital status and the risk of cardiovascular, cancer, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 7,881,040 individuals. Global Health Research and Policy, 5(1), 1–16.

Williams, J. S., Bishu, K., Dismuke, C. E., & Egede, L. E. (2017). Sex differences in healthcare expenditures among adults with diabetes: Evidence from the medical expenditure panel survey, 2002–2011. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–8.

Witter, S., Govender, V., Ravindran, T. S., & Yates, R. (2017). Minding the gaps: health financing, universal health coverage and gender. Health Policy and Planning, 32(suppl_5), v4–v12.

World Economic Forum. (2021). Global gender gap report 2021. World Economic Forum.

Zhuo, X., Zhang, P., Barker, L., Albright, A., Thompson, T. J., & Gregg, E. (2014). The lifetime cost of diabetes and its implications for diabetes prevention. Diabetes Care, 37(9), 2557–2564.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gupta, I., Ranjan, A., Barman, K. (2024). Are Gender Budgets Necessary for Reducing Inequalities in Health Outcomes? An Exploratory Analysis. In: Dev, S.M., Ganesh-Kumar, A., Pandey, V.L. (eds) Achieving Zero Hunger in India. India Studies in Business and Economics. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4413-2_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4413-2_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-4412-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-4413-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)