Abstract

Human desire to attain the state of being well has existed since the beginning of man’s social life. Within and across cultures, people conceptualize wellbeing differently because of its multidimensional nature. Even though the perspective towards wellbeing is totally relative, it is basically connected with one’s attitude towards quality of life and life circumstances. Among the women in fisherfolk, decrease in marine resources, institutional changes, occupational diversification, and the role of Kudumbasree initiatives have created significant changes in attitudes towards being well. This anthropological research analyses the mediating effect of three socio-cultural domains such as life experience, attitude, and life satisfaction on different aspects of subjective wellbeing. Three hundred and ten women from the marine fisherfolk families in Kozhikode district of Kerala participated in the study. The structural equation modelling proposed in the study revealed the significant influence of above three domains on subjective wellbeing with the support of thirteen sub domains including health and hunger. The model also reflects the signifiers relevant to the life satisfaction of women in a particular socio-cultural, economic, and environmental setting. The findings of the study have ethical and applied implications, if subjective dimensions of wellbeing are considered in the preparation of public policies for women and thereby attaining a life circumstance where there is zero hunger.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Human desire to attain the state of being well has existed since the beginning of man’s social life. Within and across cultures people conceptualize wellbeing differently because of its multidimensional nature and the perspective towards that concept is totally relative. Though the notion of wellbeing is directly and/or indirectly connected with one’s attitude towards quality of life, measuring subjective wellbeing is an essential component of measuring quality of life. Raibley stated that ‘a person enjoys high levels of personal well-being or welfare when their life is going especially well for them’ (2012: 7). That means, personal evaluation of one’s life (which includes life satisfaction from attaining tangible and intangible assets) is very important to assess the extent of wellbeing experienced by a person. It is established (Diener et al., 1995; Steel et al., 2018; Krys et al., 2019) that evidences connecting the wellbeing of individual and society is based on averages of personal life satisfaction ratings from members of the society. Krys (2021) wrote that ‘recent cross-cultural studies of well-being have introduced the concept of interdependent happiness (Hitokoto & Uchida, 2015) as a more relationship-oriented view of happiness—emphasizing harmony with others, quiescence, and ordinariness. All types of happiness probably share a common core, but emphasize different aspects of happiness: interdependent happiness is more relationship-oriented and life satisfaction tends to be more achievement-oriented’. According to Veenhoven, happiness is synonymous with subjective well-being and can be defined as how individuals rate their quality of life favourably (1984). In short, the subjective approach examines people's subjective evaluations of their own lives.

Regarding the objective of anthropology in the study of happiness, Mathews and Izquierdo state, ‘sociocultural contextualizing that can enable us to make sense of how people in different societies feel about their lives’ (2009: 259). Anthropology offers that, happiness and wellbeing are abstract cultural constructs which one cannot observe, instead understand what is regarded by the research community as ‘happiness’ or ‘being well’ which can make them happy in their socio-cultural setting. To substantiate, Sarvimaki (2006) opined that wellbeing is most usefully thought of as the dynamic process that gives people a sense of how their lives are going through the interaction between their circumstances, activities, and psychological resources or ‘mental capital’.

Anthropology also insists on the fundamental role that culture plays in providing a specific set of conceptions which directs an individual to achieve the state of feeling well. Suh in ‘self as the hyphen between culture and subjective well-being’ explains the importance of ‘self’ in maintaining the functioning of social institutions to achieve the state of wellbeing across cultures (2000, p. 63). Since social institutions are fundamental aspects of any society, the emotional support it provides to individuals is significant. This is especially true in societies where people are engaged in collective means of subsistence making which is very much challenging from the point of view of risk factors and uncertain in the availability of resources. In such societies where economic activities are collective and cooperative endeavours, subjective and collective well-being are complementary to each other.

Flanagan (1978) and Pullium (1989) considered wellbeing as a construct defined by the level of satisfaction of different factors of life such as health, family and couple relations, education of children, personality, friendships, social activities, work, recreational activities, personal expressions, and creativity among many factors. Anthropological perspectives strongly insist on the prevalence of needsFootnote 1 in human society and the way adopted for satisfying needs vary according to the socio-cultural background of the individual. The feeling of wellbeing experienced by the members of society also influence external factors such as religious commitments, political interventions, aspects of mechanization, ecological conditions, economic constraints in occupation, and social institutions. There are institutional structures and practices that allow the society to deal with conflicts if any, and these structures function well to treat every member of that group in a compassionate manner to help in developing individual perceptions. These individual perceptions substantiated with life experiences (hunger, poverty, and trauma) and personal qualities (such as interest, optimism, confidence, anxiety, anger, and level of autonomy) define the health status (both physical and mental) of people which is also a key factor of being well. In short, the different dimensions of well-being are independent, and to attain a comprehensive understanding of well-being, multiple dimensions are required to be measured.

While discussing subjective well-being, individual life experiences (hedonic) play a significant role as explained by psychologists. Ryff (1989) emphasized that factors (eudemonic) such as autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, life purpose, mastery, and positive relating, are responsible for psychological well-being in contrast to subjective well-being. However, anthropological interventions place individual life experiences and personal conceptualizations as significant factors from the perspective of culture and socio-ecological settings. So, it seems necessary to explore what people think about wellbeing as embedded in the world of meanings/values construed by a unique cultural tradition. This anthropological study is based on the understanding that subjective well-being is considered to be a multidimensional construct that denotes the satisfaction of many factors and subjects related to the diverse areas of people’s lives. So, in this study, a combination of both objective and subjective factors is given emphasis from an anthropological perspective for explaining the state of wellbeing experienced by the women in marine fisherfolk of Kerala.

2 Significance of the Study

Even though the fishing villages in Kerala have different appearances in terms of layout, conveniences, and resource mobilization, there are many problems of similar nature which the fishermen experience for the last many years. First is the set of fundamental facilities and systems that support the sustainable functionality of households in specific and society in general. According to them, infrastructure provides facilities essential to enable, endure and empower societal living conditions and are objective factors towards community and individual life satisfaction.

Marine fishers are close-knit societies because of the nature of their traditional occupation. Since marine fishing is a group activity involving the participation of persons from different (mostly) families, a community/societal level wellbeing is expected by the members. Even though mechanization has created a certain level of competitions and progressions, the individual relationships materialized through social institutions and social dependence are found strong among them (Ramachandran, 2021). Attitude of fisherwomen towards factors influencing life satisfaction at individual/collective levels decides other sectors of their life and culture. So, attitudes are highly significant from the point of view of life satisfaction.

Among the marine fishers everywhere, ‘uncertaintyFootnote 2 of resources’ is a major economic concern. Nowadays, the influence of social media, changing cultural traditions, political interventions, constraints in the availability of marine resources, climate change, occupational diversification, and dissatisfactory development interventions affect people’s perceptions towards life. Individual experiences may vary which can act as catalyst in manifesting emotions to attain a state of mind with the feeling of wellbeing. In a society like the marine fishers, subjective wellbeing is considered as the by-product of several factors which has a strong thrive on social environment and culture.

In short, this anthropological research analyses the facilitating effect of life experiences, attitude, and life satisfaction on subjective wellbeing among women in the marine fisherfolk families. A structural equation model has been given to emphasize the influence of three main socio-cultural domains such as life experience, attitudes, and life satisfaction on subjective wellbeing of women with the support of thirteen sub-domains identified from the study. The model also reflects the signifiers relevant to the empowerment of women in a particular socio-economic, cultural, and geographic context where life experiences and attitude play a significant role in achieving life satisfaction. The findings of the study have ethical and applied implications, if subjective dimensions of wellbeing are considered in the preparation of public policies for women and thereby attaining a life circumstance where there is zero hunger and poverty.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Study Area

Kerala is one of the important maritime states in India, with more than 1,000,000 of its population engaged in the fishing industry (Govt. of Kerala, 2012). The coastal line spread over nine marine districts of Kerala such as Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, Alappuzha, Ernakulam, Thrissur, Malappuram, Kozhikode, Kannur, and Kasaragod. Based on marine fish production in Kerala, the districts of Kozhikode and Alappuzha are among the leading coastal districts and marine fish consumption is also high in these districts. In the coastline of Kerala, the marine fishing population is found spread along the 590 km coastline in 222 densely populated marine fishing villages having clusters of settlements with no wider than half a kilometre from the seafront (Matsyafed Information Guide 2015). The vulnerability index developed based on demography, occupation, infrastructure, climate components, and fishery components for the coastal districts showed that Alappuzha District had the highest vulnerability followed by Kozhikode and Thiruvananthapuram (Shyam et al., 2014). Among the nine marine districts, Kozhikode district is the highest in number of fishing villages (Matsyafed Information Guide 2015). Based on these factors Kozhikode district was selected for the present study.

The coastal line of Kozhikode district has a length of 71 kms with 34 marine fishing villages. According to the Kerala Fishermen Welfare Fund Board, Directorate of Economic and Statistics, the fishermen population constitutes 97,987 in number among which 21,769 are active fishermen (2016).

3.2 Selection of Respondents

The study was started in March 2020 but due to severe COVID situations in Kerala, continuous fieldwork was interrupted many times. In the initial phase, a household survey was conducted across 300 marine fishing families representing all the 34 fishing villages in Kozhikode district. Two different types of fishing families were identified in this study: (1) active fishermen families where one or more members of the family (e.g. father, husband, or son) are actively engaged in marine fishing; (2) families diversified from within the fishing industry with less dependence on fishing as a subsistence activity. Within these two groups, the selection of families was done based on parameters such as complete dependence on fishing activities, average family size, and socio-economic factors. The primary data from the above families were collected using a pre-structured interview schedule that included details on general particulars of families, educational status, assets, debts, marital status, occupation, and material possessions. Based on the family survey, a convenient sample of 310 women above 20 years comprised of housewives, fish vendors, women working in landing centres, and women employed in non-fishery sectors were identified for intensive study. These women were mainly from married, unmarried, and widow categories. It is significant to add that, not a single divorcee was identified in the sample as divorcee rate is negligible among them. A pilot study was conducted with a draft questionnaire to test its feasibility in the field and final draft was prepared with suggestions received from community members through focus group discussions.

The main research tool was questionnaire prepared in the local language with objective indicators of information on economic activities, education, enrolment in self-help groups, access to amenities and material assets along with subjective questions on self-evaluation of life satisfaction, attitudes, and life experiences category. A total of 65 closed-ended questions with both binary and multiple responses were given in the questionnaire. According to convenience, structured and unstructured open-ended questions were operated during focus group discussions and group interviews. Questionnaire was distributed through Kudumbasree (SHG) units in each fisheries village and all the 310 women identified during the survey responded to the questionnaire. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to examine a hypothesized model of causal relationships among socio-cultural, economic, ecological and emotional variables, individual life experiences, and subjective perception of well-being using AMOS graphics.

3.3 Data Collection and Limitations

This anthropological research is based on mixed methods focusing more on qualitative methods to derive quantitative model of subjective perspectives on wellbeing. In order to elicit information on the research problem, intensive fieldwork was conducted in the fisheries villages in Kozhikode district. Anthropological techniques such as observation (non-participant), interview, genealogical method, questionnaire, and case study were adopted for collecting information from the field. Using the genealogical method, the status of active fishermen and the number of persons (both male and female) involved in fisheries-related jobs was traced. Genealogy of all the women respondents was taken for clarification of qualitative data. Observation was made to understand the interactions of women in real-life situations such as at family level, during Kudumbasree meetings, and other situations where interpersonal interactions took place. Focus group discussions were made under strict COVID protocols. Since coastal areas of Kerala were exposed to speedy spread of the pandemic, data collection was interrupted many times. However, with the help of SHG officials (mainly Kudumbasree), women informants were contacted a number of times for clarification of responses submitted in the questionnaire. The informants extended strong support in filling the lengthy questionnaire because of their interest in responding to highly personal questions related to wellbeing which was never been asked by any officials from administrative or development departments. Telephonic probing was done in some of the areas where the informants were in containment zones. Restrictions on COVID-19 curtailed the close observation of informants in their natural setting was one of the limitations of this study.

4 Empirical Realities

The infrastructural facilities availed by a population serve the function of basic amenities to overcome the inconveniences in many aspects of life. In this study, the lack of own house is a concern reported by the women. One fourth of the informants still live in rented houses or with their relatives. In most of the fishing villages in Kerala, fishermen's houses are agglomerated in nature and fishermen are not interested to shift their residence to a distant place away from their friends, relatives, and workspace. In some cases, the prevalence of joint households is one of the reasons for the absence of separate houses for individual families. It is also noticed that four families with independent ration cards are staying under one roof. However, all the houses are supplied with power supply and drinking water. The provision of toilets and power supply to 95% of households is reported as an attainment of government and NGOs in providing basic amenities in an effective manner. Fisherwomen opined that ‘equal access to basic facilities to all families reduces the competition between families and also help to create a feeling of community wellbeing’. In a focus group discussion, the activeFootnote 3 fishermen also admitted that community wellbeing is very much significant as they share the same social and geographical area as part of their subsistence activity for survival. Since marine fishing is a joint endeavour, group harmony is very much necessary to face challenges in the sea and also in the entire process of fishing starting from catch to distribution.

It has been observed (Ovstegard et al., 2010; Sumagaysay, 2011) that, impacts of societal and other fluctuations tend to be more severe on women. In India, marine fisheries sector was based on high degree of gender division of labour and women were subjected to differential access to marine resources, technology, decision-making process, and political participation. The objective of SHG like Kudumbasree to bring forward women to obtain empowerment is found gaining results considering the gender-specific contributions in livelihood securities in the families across Kerala. The women in fishing communities are also not an exception to this development. In this study, participation of women in post-fisheries activities is nominal and involvement in SHG activities provided them with income to support family expenditure. This has also created the feeling of economic independence which is highlighted as one of the factors leading to life satisfaction (Fig. 1).

The uncertain nature of marine resources never always substantiates the fishing families with sufficient income for an affluent living. So, the fisherwomen strongly suggest that right-time interventions from the part of government are mandatory for their minimum survival. In this study, 92% of the women respondents are formally literates and they admitted that accessibility to schools is one of the advantages that helped them to pursue education even in the middle of economic crises in families. Since membership in Self Help Groups like Kudumbasree does not require formal education, the illiterates could also avail opportunities under National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme (NREGP). Women admitted that it was an absolute support to their families during economic exigencies. 94% of women in this study are enrolled as Kudumbasree members which shows the successful attainment of a public policy initiative by the State government.

In fishing societies, the role of women is important from the livelihood and nutritional point of view at the household level. Besides this, the larger environmental, socio-cultural, and political framework within which they are embedded also has an impact on their contributions to family and society. Comfortable socio-cultural environments encourage to create positive emotions which help individuals to expand their social involvements in ways that create overall satisfaction with life. In the light of empowering fisherwomen, it is essential to bring into perspective their personal assessment of individual characteristics in developing an attitude towards the process of life satisfaction.

Chang and Sanna indicated that optimism had a direct link with life satisfaction, positive affectivity, depressive symptoms, and negative affectivity (2001). While asked about individual characteristics based on a personal assessment (Fig. 2), out of the total three hundred and ten women, 95% admitted that they are optimistic towards the present-day life situations. It is identified that the non-optimistic informants belong to a group of widows and unmarried women. The higher rate of confidence expressed by women highlights the empowerment they achieved through economic participation and self-dependence. Women admitted that, now they are capable of managing activities outside the family, and this achievement they dedicated to Kudumbasree initiatives. One fourth of the middle-aged women rated themselves ‘stress free’ and these women are found with better social and economic backgrounds. This response supports the understanding that stress is an emotional state resulting from a particular relationship between the individual and the social environment. The character of short temperedness was higher in the age group of 25–40 and they admitted that it is an undesirable emotion which is totally out of their control. It is significant to note that 99% of the respondents expressed their ‘commitment in the day-to-day affairs of the family’ which they consider as fundamental in sustaining both individual and family well-being. However, self-evaluation of life aspects plays a central role in providing an inclusive measure by which relative significance of the framework for better life can be compared.

Generally, in societies with similar subsistence patterns, people have relatively same requirements and the ways used to institutionalize these requirements vary according to their socio-cultural situation. The adaptive strategies which culture provide fluctuate through a process of individual-society interaction and changes in the attitude of the individual. This may happen at any level within cultures and the quality of life of persons should be based on their own evaluation of being well. In this study, the family of 95% of the informants depend on unreliable resources from marine fishing. So, the income is also unpredictable. With the advent of mechanization in marine fishery, the traditional social set up of the fishermen families underwent many structural and institutional changes and 45% of the women reported it as an unsatisfactory situation to them.

Before mechanization, fishing was a combined effort done by groups of people from the same household or neighbouring households and that unity gave individuals and families an emotional strength to overcome the obstacles in their life. Also, the occupation-based group life for extracting common property resources usually reduces the space of ‘individual’ when compared to ‘group’. Group was significant in the path of survival and with this reason joint families survived for long among the marine fisherfolk. Their feeling of well-being was also retained with group living and activities, and the function of need was to pay more attention to the ‘group’ than to the self. Women admitted that, even though joint families have its own barriers in some of the life aspects, the overall function it sustains is comparatively higher. Here, it is understood that the person is socially oriented and the pursuit of socially desirable and culturally delegated attainment is the supplementary approach of the socially oriented personhood.

In this study (Fig. 3), 75% of the respondents expressed that joint families were safer and provided them with all security and emotional strength. In joint families, participation of the kin group in fishing expeditions, professional socialization, and training within the kin group, provided them emotional support to face any kind of challenge. Even now elder women in fishermen families perceived wellbeing as a group feeling and stated that, in joint families, any external disturbance affecting family’s welfare was handled unanimously with the involvement of all family members.

During focus group discussions women reported that integration of workplace, habitation, and occupation-based settlements with a large number of families are supportive factors for their safety and emotional comfort. It is significant to note that respondents (96%) from the age group of 50 years and above expressed concern about the safety and security of their children because of the disintegration of joint families. Older women in the study stated that the harmony and comfort they experienced in joined families provided them with the feeling of wellbeing and they never experienced it in nuclear families. Earlier, fishermen involved in deep sea operations were unable to predict the time of their return because of the uncertain nature of fishing. So, women undertook the entire responsibilities of children with the support of other family members. But, younger generation especially women below thirty years of age and all from nuclear families shared that they (64%) are not concerned about the structural changes in family environment. These two perspectives from two generations clearly show the shift of wellbeing paradigm from collective to a totally subjective one. Convenience of managing the income, personal freedom, decision-making role in family, and availability of more leisure time are the reasons they highlighted to substantiate their position. Young women shared that ‘even though joint families provided safety and comfort, personal freedom for women was not there which led to low level of aspirations’.

Like any other global community, fisherfolk are also undergoing changes in the realm of society and culture.Footnote 4 It is a fact that all changes in the socio-cultural sector are not equally significant. Some changes turned mandatory as they are considered necessary for human existence. Some other changes are accepted in order to satisfy socially acquired needs that are not essential for survival. Changes in food culture and costumes are in the second category. The positive impact of food intake on well-being is not limited to the type of food people consume but extends to the way they consume, the environment, and the socio-economic factors related to eating. Since food is an important aspect of culture and women are closer to food-related activities, changes in this cultural trait are significant from the perspective of wellbeing. Here, 70% of women from all the age groups expressed less concern about the changes happened in food culture. Moreover, they shared a positive attitude towards such changes saying that a new fashion dress or a new food item would give them happiness. This notion of happiness substantiates the statement given by Sara Ahmed that ‘happiness is always associated with some life choices’ (2010: 2). It is also seen that more than 50% of women are not bothered about the changes in celebrations associated with life cycle rituals and practices. According to them, they try to attach wellbeing to new activities and involvements and the subjective experience they derive from these engagements is used for converting opportunities for individual and social wellbeing. In this study, the importance of social context as a determinant of well-being and quality of life is clear in the expressions of women.

In India, environmental disasters and subsequent degrading of ecosystems badly affect biodiversity and the availability of natural resources that support people’s livelihoods. Marine environments are also not exempted from this phenomenon. From the study (Fig. 4), it is understood that the women are much aware of the decline of marine resources and the deterioration of the coastal environment. Ninety-eight per cent of the women expressed their anxieties about the fluctuating nature of economic conditions due to the decrease in marine resources. These women were from families solely depending on income from marine fishing and they strongly believe that life situations including wellbeing will be seriously affected by a decrease in marine resources. The remaining 2% comprised of women from families where marine fishing is not the primary subsistence activity. These families have men working in Gulf countries, employed in State government services, and also in local private jobs.

Faith was considered a significant part of life for the majority of the respondents. The focus group discussions conducted among the informants showed significant intergenerational differences in opinions regarding this aspect. The older generation (above 60 years) stated that the constraints in life will never affect their faith in God as the later they believe, gives emotional support in all critical situations. Even though many of the fishermen are affiliated with a political party which does not support faith in God, women consider these as two parallel lines. They also (72%) admitted that their attachment with the sea will never be affected by a decline in marine resources because they trust the sea as ‘mother goddess’ who provides their subsistence and they prefix everything with this faith.

In a study across twelve countries, Krys et al. found that family-interdependent happiness refers to the collective happiness of one’s family and the extent to which one’s family is in harmony with other families and groups in one’s community (2019). In this study, 76% of women opined that traditional work patterns in fishing operations had strengthened the social relationship among fishermen. The unity and cooperation within a fishing group gave them a comfortable working environment during unfavourable climate conditions in the sea. Women reported that earlier sea-going workforce comprised of kinsmen from the same family or neighbouring families and this has provided a strong social and familial bonding. This unity among men during and after fishing operations gave women emotional support and confidence to send their men to an occupation which is totally hazardous. They strongly believe that the kind of interfamilial support, social interactions, and the practice of sharing resources they experienced with clustered living, substantiate their feeling of wellbeing in the midst of economic crises and unsafe environment. It is significant to note that 60% of women supported (Fig. 5) the current trend of the younger generation to shift from traditional occupation to other job sectors. This opinion is validated by the percentage of women (56%) who expressed dissatisfaction towards low income from fishing. They (92%) are of the opinion that a decrease in income from fishing will definitely affect their family life. However, 85% of younger women respondents in the study strongly opined that, they are not at all satisfied with the income from fishing.

Elderly women (above 60 years) in the study expressed the economic freedom they experienced while managing the entire household expenditures. Earlier, sea-going fishermen handed over the entire earnings to their women who controlled the family expenditures. Women claimed that they could manage the family in a balanced way without much debt. But, with the advent of mechanization, the situation has changed and the activeFootnote 5 fishermen in the younger generation are found reluctant to give their earnings to women. Instead, they started to manage family expenditures and spent large share of their income for habits such as drinking alcohol and smoking. During the study, this tension was shared by women of all age groups and 53% of women (especially above 60 years) expressed their worries about family management mainly due to the changes in traditional occupational sector. Beyond generational differences, women expressed that the excess alcohol consumption of men creates problems in most of the families which lead to a state of decreased wellbeing, especially for women and children.

It is a fact that income from fishing has decreased nowadays and the new generation of fisherman families started to choose other diversified job sectors for subsistence. The genealogical chart (Fig. 6) of a joint family shows the decreasing involvement of men and women in active fishing and post-fishing works. The women who engaged in fishing from two generations were unmarried and in the third descending generation no women are found doing fisheries-related works. The number of active fishermen is also found reduced in the descending generations. With the increase in household expenditure, it is difficult to manage the family with a single source of income and they used to avail microcredits from government and private sources. 70% of women expressed that the decision to take microcredit was a joint decision by the family and their involvement in familial income generation helped them to elevate the decision-making power in family.

In the marine fishery sector of Kerala, participation of women is absent in the production process and it is completely handled by men. Even though technological aspects are highly developed to extract maximum marine resources, women are normally discouraged to do fishing operations in sea waters because of the high-risk factors involved. However, they were involved in post-harvest activities as part of division of labour. Fisherwomen opined that those technological changes due to mechanization and resultant labour concerns have made changes in the marine fisheries economy unfavourable to women. They were much aware of the situation and 64% addressed the issue with great concern. But the rest of the women opined that mechanization was beneficial to the fishermen society from an economic point of view. They also highlighted the comparatively less risk factor involved in fishing with improved fishing technologies. It is found that most of the fish landing centres in the study area, participation of women in the post-harvest activities was replaced by the service of migrant male labourers appointed by the local fish merchants.

Earlier there was no mechanism to know the welfare of fishermen while they engaged in deep sea fishing. But the efficient Information and Communication facilities now provide easy access to fishermen at sea to communicate the warnings from official centres. One of the younger informants said; ‘When technologies become efficient, we rely more on technology instead of relying on God. This gives us more confidence and optimism for sending our men to fishing jobs. During the time when technology was not that much efficient, faith in God and human relations were strong and ardent’. Elderly women (27%) admitted that the present situation is not at all supportive to their state of wellbeing because of the changes in earlier social realm which they found more comfortable. Dissatisfaction was shared by the respondents (45%) towards the loss of personal relationships due to changes in local distribution of fish. Their personal relationships with women from other Castes and Communities outside the jurisdiction of beach helped them to avail financial support whenever required. But the change in distribution system after mechanization has reduced their involvement in local marketing and their space is limited to a corner of the fish markets. Distribution of fish by taking as head loads has totally stopped in the area.

Religious believes and practices play a central role in the life and culture of people, especially among those living in unfavourable environments such as coastal ecosystems. The challenging nature of environment will bring people closer to faith and it is established that (Hackney & Sanders, 2003; Oishi & Diener, 2014) the worldviews, beliefs, and thoughts along with actions, rituals, and practices provide an effective wellbeing to people in different cultures. Among the marine fishers, faith in God and belief system are strong components that support the emotional wellbeing of people, especially women. It is found that like any other traits of culture, believes and practices are also undergoing structural changes along with the transformation of society. In this study, 67% of women opined that they never felt unhappy with the changes in traditional rituals and practices. Women (54%) of all age groups opined that they are more comfortable with the new system of practices in belief system as the old ones are more rigid and gender biased. During menstrual periods, they were totally isolated from all the household activities with the cause of touch pollution and the elder women imposed strict restrictions on them. During focus group discussions, women admitted that they were emotionally disturbed with these restrictions. But now, these practices were found almost vanished and the younger generation is not willing to follow the old customary practices associated with life cycle rituals. 93% of women (Fig. 7) expressed interest in sharing their experiences with younger generation even though the later are not interested to listen them. According to elderly women, they (67%) are trying to adjust with the new world view of younger generation to maintain harmony in the family. They used to engage in prayer, reading religious texts, or listening to devotional songs so as to attain emotional wellbeing.

The health and wellbeing of people at all ages is one of the significant goals of sustainable development. At present the evaluation of individuals’ health status and well-being extends beyond traditional indicators of disease, infirmity, concept of health, and health care approaches. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,Footnote 6 suggested a range of factors as ‘underlying determinants of health’ for helping individuals to lead a healthy life. Safe drinking water, adequate sanitation, clean food, healthy working space, and environmental conditions are also added to the list of factors identified as determinants of health. It is a fact that the health outcomes and disparities are driven by socio-cultural and economic determinants and this is especially true in the case of societies such as the marine fishermen.

Information (Fig. 8) on the experience of hunger shows that women experienced hunger during childhood and they had times when there was insufficient food. A cross-examination on economic status and experience of hunger highlights the role of occupation, increased number of persons in a family, and the status of food consumption. Earlier, in fishing families, the number of children was more and the income to afford a large family was insufficient. As persons engaged in a hardship job, men were provided with good food in sufficient quantity which always resulted in insufficiency for women. One of the women (70 years) informants said, ‘Mothers provided quality food to sons. We experienced hunger after procuring, cooking and serving the food. Some of the days we didn’t go to school because of hunger. For our complaints mothers used to say that boys are earning members of the family and they are doing a tiresome job to safeguard family members. So, we were inculcated with the notion that women have to tolerate hunger and no concern was given to our health issues’. Women admitted that, now the situation has changed and food is not a matter of concern to the present generation provided one must have money to buy it.

Health issues such as intestinal ulcer and problems of digestion while taking certain food are reported by the women. Elderly women strongly believe that acute poverty experienced during childhood was one of the reasons for present intestinal problems. The women who experienced hunger substantiate that low income was the main reason for hunger. Older women (comprised of widows and unmarried) with some sort of physical discomforts and ailments expressed dissatisfactionFootnote 7 on the irresponsible attitude of family towards their health issues. Contrary to this, younger women (84%) supported the concerns of family towards them after a shift in the position of women from consumer to producer of income. This intergenerational difference in opinion made it clear that contribution to family income and subsequent role in family’s decision-making process supported younger females with all attention from the family members. From this study, it is understood that income generation by the females and their contribution to family economy are indispensable factors for reducing poverty at family level and helping them to reach a situation where there is zero hunger. 65% of younger women admitted that they have no difficulty in availing any job outside the jurisdiction of beach. However, they prefer to reach family every day to look after the family affairs.

It is significant to note that, in the sample of study, 94% of women (n = 310) enrolled in Kudumbasree and they agreed that this involvement has increased their economic independence at household level. However, 43% shared that, due to the increased burden of managing family, their earnings are not sufficient for meeting very personal needs. 61% strongly admitted that they acquired an economically independent status in the family and 79% of Kudumbasree members unanimously admitted that their role in decision-making at family level increased because of this initiative by the government (Table 1).

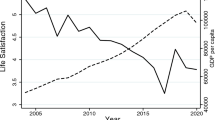

In the social gerontological literature, happiness, life satisfaction, and morale are the main indicators of Subjective Wellbeing (George, 1979). The positive and negative emotions on over all life domains associated with expectations about the future constitute the level of wellbeing experienced by an individual. Social comparisons, life reviews, and state of happiness are the explanatory tools used to filter information from individuals to define the quality of life. During focus group interviews to discuss personal life experiences, women clearly articulated their attitude towards accepting transformations in society. Without intergenerational difference, 50% of the women expressed their mindset to accept any kind of socio-cultural change. However, the older generation highlighted worries on changes that are harmful to younger generation. In their opinion, ‘the values, ethics and morale showed by ancestral generation gave strength to the society to face any kind of challenges. But the good elements of society are now found vanishing and younger generation has no commitment in fulfilling social responsibilities’. Older women also revealed that they are constantly trying to focus on their weaknesses and possibilities as part of adjustment which is considerate to other’s needs and social mandates (Fig. 9).

Lawton, Morris, and Sherwood considered attitude towards own ageing as a factor in apprehending the individuals’ perceptions of changes taking place in their lives, and their evaluation of those changes (1975). Here, 13% of the women (all of them above 70 years of age) were found emotionally disturbed while explaining their experiences with the younger generation. They admitted an absence of happiness and satisfaction in the present socio-cultural set up of the society. However, most of them are under the impression that people of their ages have good relationship with each other which gave them moral support to overcome obstacles in life situations. It is understood that older adults do not place much importance on individual status and money as that of younger generation, but they tend to place more value on family relationships and long-term fulfilment from one’s life. In short, 75% of women under study expressed that they are satisfied with the present-day life situations only to a certain extend.

Emotional well-being can be conceptualized as the balance of positive and negative feelings experienced in life and the perceived feelings such as happiness and life satisfaction. It is a general attitude among the people that, involvement in day-to-day affairs of the family and healthy interaction with other members of the society help to develop a satisfactory attitude towards life. In the present study, 86% of the women stated that they feel happy while mingling with others, especially relatives and friends. They added that they have no hesitation to interact with others because of the involvement in Kudumbasree activities. One of them added, ‘internally we had differences in opinion but, the overall group activities provided us with emotional support to move forward’. Majority of women (88%) expressed that the engagements in Kudumbasree activities made them positive towards life. Those who hesitated to express their opinion or took a neutral position during discussions comprised of women above 70 years, unmarried women, and women with chronic diseases. However, it is significant to note that only 71% of women expressed satisfaction towards governmental interventions in the overall development of fishing community. Remaining (29%) women could support their arguments by highlighting the loopholes in development interventions. Differences in political affiliations and preconceived notions on ruling parties are identified as some of the reasons for these comments. The ability achieved by women to express their opinion for and against any issue is a positive indication of their empowerment and beyond political affiliation all of them dedicated this achievement to Kudumbasree initiatives.

Even though they are busy with everyday life, 88% of women revealed that the health aspects of family and anxieties on the future of children continue to disturb their emotional wellbeing. It is significant to note that none of the respondents was interested to send their children to traditional occupation of fishing. They agreed that high-risk factors involved in deep sea fishing along with low income restricted to take such a deviant thought in opting fishing as a subsistence activity. At the same time, women (64%) expressed optimism towards the changes happening in traditional occupational sector. They opined that the new fishing technologies, marketing strategies and resource management system are giving an elevated status to fishing even though there are many challenges in the fisheries sector.

It is an established fact that listening to music has the characteristic ability to decrease the psychological stress response. Research (Kallinen & Ravaja, 2004) claimed that listening to music is mainly for getting relax and improving people’s mood and also for decreasing negative emotional states such as anxiety and stress. In this study, women (98%) of all age groups expressed that they are very fond of listening to old songs. Elderly women said that listening to music reduces their tension and younger women opined that music make them happy. Nowadays, they create small groups of 1–10 members and used to recite religious texts such as Ramayana and Bhagavata in temples. They complained that younger generation (below 20 years) is not interested in such activities and over-emphasis on social media and other entertainments withdraw them from traditional cultural practices and faith. Elder women strongly believe that the present-day problems in the society are mainly due to the deviance from traditional norms and practices shown by the younger generation.

Participation in local political parties is one of the reasons expressed by women regarding the deviance of young men from family responsibilities. It was reported that women had no representation in mainstream politics and they (71%) expressed annoyance towards the interventions of politics in community affairs. The present political scenario of the study area is not favourable for a healthy political work and 82% of women in the study expressed strong disagreement withn the participation of their men in local politics. However, 18% still believed that political interventions will definitely stand for societal development. This section of women admitted that they received governmental aid with the help of political parties. Women supported the role that fishermen organizations play in helping the fishermen to avail benefits from the government and NGOs. But they are least interested in affiliating these organizations with ruling or opposition parties.

Life evaluations have been considered a central role in the assessment of wellbeing because these provide an umbrella measure by which the relative role and significance of the supporting pillars of quality life can be compared. Ruut Veenhoven defined life satisfaction as ‘the degree to which a person positively evaluates the overall quality of his/her life as a whole. In other words, how much the person likes the life he/she leads’ (1996). In this study, an evaluation of life satisfaction shows that 45% of women expressed dissatisfaction in the present life situations. Major reasons reported by women include personal health issues and health issues of family members, financial issues, absence of a safe shelter, lack of pure drinking water, lack of employment for children, declining marine resources, weakened social control mechanism and decreasing strength of kin relations. External factors such as unsatisfactory development interventions, lack of sufficient employment opportunities for men, political interferences in community and family affairs, lack of proper infrastructural facilities are the major external factors reported as influencing their life satisfaction. Basic insufficiencies in families are also reported as factors for unhappiness. When asked about the attitude towards complete happiness, 81% women reported that they never experienced such a state of mind. This is because of the reason that they value happiness of the whole family over personal happiness. From this study it is understood that, the conceptual relations regarding the extent to which societal wellbeing is a fundamental component of individual wellbeing is stronger in collective societies like the fishermen.

Among the 310 women selected for the study (Fig. 10), the frequency of respondents shared unhappy state of mind were almost same in the age group of 30–40 and 50–60. However, the frequency of women who agreed that they are ‘happy to a limited level’ shows an increasing trend from 20–30 age group and then found decreasing to 70–80 age groups. The number of women in this category are more from the age group of 40–50 and it is important to note that all of them are members of the Employment Guarantee Programme (MGNREGA) of the Central government. The involvement in this Programme ensures them economic security which has been addressed by them as one of the important factors towards happiness. When examined the status of women who expressed as ‘happy’, it was seen that they (19%) are one of the earning members of their families. Even if some of them have no involvements economic activities, family’s welfare is safe with other members, especially husband or son. Moreover, they agreed that their family environment and kinship networks are strong to face any external challenges. Dependence on active fishing is nominal in their families and at least one member of the family is engaged in jobs other than fishing or post-fishing activities. In the age group of 20–30, only one woman has stated unhappy and she belongs to a family where three persons died from the sea during fishing operations. It is significant to note that all the three levels of happiness are found decreasing in the age group of 70–80. It is understood that every unhappy woman in this study has her own justifications and reasons for that state of mind.

5 Analysis and Interpretations

In a community like the marine fishermen where ‘common property resources’ are used for subsistence; it is important to understand that socially oriented conceptions of wellbeing are composed of role obligations in family and society. In the middle of her kinship obligations as daughter, wife, mother, and grandmother, a woman always strives for familial wellbeing and her individual state of wellbeing and happiness are centre around personal accountability. This obligation was ardent in joint families. Here, in addition to her husband, children and parent in-laws, she has to consider the welfare of other members also. In Kerala, most of the joint families of the fishermen are horizontally extended with brothers (both married and unmarried) live together in one house along with the parents. So, as daughter-in-law and sister-in-law a woman has to bear many responsibilities in addition to the commitments towards her husband and children. Earlier in joint families, in addition to the kinship obligations she was entitled to manage the cultural traditions through organizing celebrations at family level and managed the function with her overall supervision. In short, a woman is placed in a nexus of responsibilities (Fig. 11) to maintain joint wellbeing in families. Nowadays, it is seen that those who are economically stable and capable to live independently leave the joint family and establish separately.

From an anthropological perspective, the notion of wellbeing is culturally conceptualized and so culture is the central force for the construction of happiness and wellbeing with the support of subjective experiences. Here, societal interactions help individuals to maintain cultural traditions with the support of social institutions and this provides a state of ‘social comfort’ as stated by the fisherwomen. Luo LU states that culture influences SWB (subjective wellbeing) through multiple mediators and complex mechanisms that encourage and/or reflect the person as an individually oriented or a socially oriented entity (2008). During focus group discussions elderly women in the study emphasized the importance of this nexus of relationships in providing emotional strength to a woman in the middle of economic constraints and also in handling health issues. The ultimate goal of a woman in a family focused on familial wellbeing rather than individual. The folksongs and stories among women clearly depict these responsibilities, moralities and obligations. It is also understood from the study that, these attitudes are found changing in younger women and their likes and dislikes are limited to individual families. The new ways of identity formation supported through governmental initiatives and education provided them with confidence to manage activities without the support of a joint family.

When examined the status of women who expressed happiness but not satisfied with life situations, it was seen that all of them were married and belong to families fully depending on fishing. They admitted that, ‘there is no absence of food, experience of hunger and other conflicts in the family which make us unhappy. The absence of material possessions including land and own house are lacking which affect our life satisfaction’. Women (17%) who expressed ‘unhappy’ comprised of widows, those having chronic physical sufferings, those with traumatic experiences such as loss of beloved ones, unmarried ones depending on siblings and also elderly women who are helpless to manage one’s basic needs. During discussions at various levels these women expressed grief for depending others for all their daily requirements. Wellbeing among these women relates not only to their health but also to whether their needs are met such that one can enjoy a satisfactory quality of life. Dissatisfaction and unhappiness impact health, both physical and psychological and may affect relationships between kins and social institutions.

Here, the self-reported state of happiness and/or life satisfaction is subjective and it does not mean that it has no relation or connection to relatively more objective factors. In this study (Fig. 12), for a question on the state of happiness, 64% of women responded that they are happy to only a certain extent. But, 61% of them shared that they are satisfied with the life situations highlighting the fact that the state of happiness and life satisfaction are two states of mind. According to Amartya Sen, ‘If a starving wreck, ravished by famine, buffeted by disease, is made happy through some mental conditioning…the person will be seen as doing well on this mental-state perspective, but that would be quite scandalous…It is hard to avoid the conclusion that although happiness is of obvious and direct relevance to well-being, it is inadequate as a representation of well-being’ (1985: 188). Happiness is a saturated and elevated state of mind which has nothing to do with material possessions and other assets. However, it is understood from this study that the role played by material assets is comparatively high in achieving life satisfaction. An anthropological model is given here to show the influence of various domains helping to create a state of wellbeing among the women in marine fisherfolk families.

The analysis of the model shows that it has a CMIN/DF value of 1.709. This value is less than 3 and it indicates an acceptable fit between hypothetical model and sample data. Also, the model has a GFI of 0.95, CFI of 0.94, RMSEA of 0.04, AIC value of 164.8, ECVI value of 0.53, and TLI value of 0.92 as the fitness indexes. Here, the high CFI value shows that there is only less discrepancy between the data and the hypothesized model. The high CFI value shows that there is less misfit in the model compared to the baseline model. The low RMSEA value shows that the hypothesized model is less far from the perfect model. A smaller ECVI value indicates a better fit.

6 Model Discussion

In the present study, the three main components identified for understanding subjective perspectives on wellbeing are life satisfaction, personal experiences, and attitude (Satisfaction, Experience and Attitude)—the SEA abbreviation. The proposed SEA model (Fig. 13) integrates both objectiveFootnote 8 and subjective components of wellbeing from a cultural perspective. The three components satisfaction, experience, and attitude are associated and influenced by other components which are essentially involved in acquiring a state of wellbeing. Among the three, life satisfactionFootnote 9 is assessed by an individual through comparisons of overall life realms mainly associated with the past and it is an activity with optimal cognitive functioning involving comparison of one’s life with others, comparison of life over a certain period of time and a total review of one’s entire life. Temperament variables such as HopeFootnote 10 (EA-h) and Self-esteemFootnote 11 (EA-i) are found contributing to achieve life satisfaction among women in addition to the variables such as Economic independence (ECON-e) and social capitalFootnote 12 (IPLE-c). A person’s life satisfaction will not be determined based on factors that he/she don’t actually find personally meaningful. It is evident that life satisfaction is associated with physical health, less unemployment and financial strains, a better ability to meet personal needs, hope, self-efficacy, more social support, and higher interpersonal and cognitive functioning. So, the measures of life satisfaction are generally subjective and personal experiences also play a significant role in substantiating wellbeing directly and/or through making life satisfaction effectively.

Well-being is regarded as a multifaceted construct. The common theme developed from various discussions on wellbeing centres around a state of ‘feeling good and effective functioning’ which involves an individual’s own life experiences and comparative assessment of life circumstances. However, anthropological perspectives insist on the importance of socio-cultural background of individuals in perceiving wellbeing from a subjective point of view. Here, women in fishing families highlighted their life experiences mainly in connection with health, hunger, and poverty due to low income from their occupation. It is found that Hunger (H-c), Health issues (H-e) Absence of health care (H–d), and Poverty (H-f) are the significant factors identified by them as painful life experiences which directly affect their attitude towards life and resultant life satisfaction. During focus group discussions more than 50% of women in the study shared their experiences in connection with hunger and poverty. One of the women said, ‘hunger is the most painful experience for a woman because she is entitled to feed others with whatever is left in a pot with an empty stomach’. When asked to make an overall assessment on life, these experiences influence them in developing an attitude which is different from their neighbourhood women.

AttitudeFootnote 13 is a mental construct influenced by a number of factors and life experience is one among them influencing a person’s overall life. In this study, it is found that occupational diversification (ECOL-e), impact of decrease in marine resources on life situations (ECOL-b), and mechanization (TECH-c) are the key factors identified as significant ones influencing their attitude. Women strongly expressed anxieties on the decreasing marine resources and they emphasized that mechanization and over fishing have reduced the availability of marine resources which in turn started to change their attitude towards fishing as a primary source of income. They also fear that, occupational diversification due to a decrease in marine resources will change the traditional socio-cultural set up of the community which has been providing them with emotional wellbeing during joint living. Attitude towards life and life experiences have positive correlations and both influence life satisfaction which is identified as the foundation of subjective wellbeing. Moreover, Age (SWB-a) and circumstancesFootnote 14 (SWB-f) also contribute a major share in developing the potential of wellbeing that people adapt more rapidly to new circumstances and life events.

7 Conclusion

In fishing societies, the attitude towards collective wellbeing is underlined as a cultural approach because it is believed to construct particular pathways for achieving individual wellbeing which fluctuates over time. In my previous research among the Hindu marine fishers, women emphasized the invisible role that they play in maintaining family-level wellbeing through the maintenance of community networks and kinship ties. In societies like marine fishers where subsistence is based on unpredictable resources, women are very much flexible in adjusting to their life situations, so that what was originally a source of wellbeing (or not being well) becomes part of the unnoticed circumstances, losing its power to influence them. The effects of life circumstances tend to be of short period because of their static adaptation to social and cultural setting manifested through social institutions. However, the infrastructural facilities, supportive environment, certainty in economy, access to non-economic resources, and life experiences are reported as some of the factors substantiating life satisfaction and well-being to both individual and at community levels. These factors influence an individual to manifest their attitude towards better health and emotional aspects which are materialized through culture and social institutions. Wellbeing in fishing communities relates not only to a single factor but also to whether their needs are met such that one can enjoy satisfactory life situations. Individual life experiences also play a significant role in the formation of attitudes towards wellbeing.

It is understood from the study that, a state of wellbeing for an individual is influenced by support from family along with the intervention of government and other agencies which can provide sustenance in the spheres of education, employment, health, and other infrastructural facilities. This is very much helpful in developing individual perceptions towards constructive action and attitude for development. The creation of a positive attitude is vital in sustaining aspirations towards one’s own wellbeing and the subsequent involvement in sustaining livelihood activities with anthropogenic management of resources. The results of the present study have implications for policy decisions and application-level research in the future for marginalized societies. Anthropological model and the analysis discussed here have significantly revealed the association between life satisfaction, personal experiences, and attitude of people which are key factors in the context of development of a community.

Notes

- 1.

Malinowski suggested that individuals have physiological needs (reproduction, food, shelter) and that social institutions exist to meet these needs.

- 2.

For the fishermen, the availability of resources from the sea is totally un-predictable because of the nature of marine environment and so economy based on such a resource system is uncertain.

- 3.

Those who still depend on seagoing as primary occupation.

- 4.

E. B. Tylor defined culture as ‘that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society’ (1871).

- 5.

Active fishermen are those still engaged in sea going and other fishing operations.

- 6.

The committee responsible for monitoring the international treaty on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in its resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966.

- 7.

A recent study on elderly individuals in China emphasized the importance of health as a primary determining factor of life satisfaction for older adults (Ng et al., 2017).

- 8.

Objective wellbeing is a measure based on expectations about basic human requirements and rights, including aspects such as own house, clean drinking water, adequate food, physical health, stable income, education, and safety.

- 9.

Life satisfaction may be measured either through a ‘global satisfaction’ measure, in which people evaluate their lives as a whole, or through a set of domain specific measures, in which people state their degree of satisfaction with different aspects of their lives (Diener, 1984).

- 10.

The concept of hope denotes a ‘positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of successful agency (goal-directed energy), and pathways (planning to meet goals)’ (Snyder, 2002, p. 250).

- 11.

Self-esteem may be defined as a person's overall subjective sense of personal worth or how much one appreciates and like oneself regardless of the circumstances.

- 12.

Social capital is defined as the ‘ability of actors to secure benefits by virtue of their membership in social networks or other social structures’ (Portes, 1998).

- 13.

‘Behavior based on conscious or unconscious mental views developed through cumulative experience’ (Venes, 2001, p. 189).

- 14.

Circumstances include own family, friendship circle, work space, and kinship networks. Circumstantial factors also include life status variables such as marital status, religious and political affiliations, and involvement in new initiatives.

References

Ahmed, S. (2010). The Promise of Happiness. Duke University Press.

Chang, E. C., & Sanna, L. J. (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and positive and negative affectivity in middle-aged adults: A test of a cognitive-affective model of psychological adjustment. Psychology and Aging, 16(3), 524–531.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 851–864. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-514.69.5.851

Flanagan, J. (1978). A research approach to improving our quality of life. American Psychologist, 33(2), 138–147.

George, L. K. (1979). The happiness syndrome: Methodological and substantive issues in the study of social-psychological well-being in adulthood. The Gerontologist, 19, 210–216.

Hackney, C. H., & Sanders, G. S. (2003). Religiosity and mental health: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42, 43–55.

Hitokoto, H., & Uchida, Y. (2015). Interdependent happiness: Theoretical importance and measurement validity. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 211–239.

Kallinen, K., & Ravaja, N. (2004). The role of personality in emotional response to music: Verbal, electrocortical and cardiovascular measures. Journal of New Music Research, 33(4), 399–409.

Krys, K., Uchida, Y., Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2019). Open society fosters satisfaction: Explanation to why individualism associates with country level measures of satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14, 768–778.

Krys, K., Park, J., & Adamovic, M. (2021). Personal life satisfaction as a measure of societal happiness is an individualistic presumption: Evidence from fifty countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 2197–2214.

Lawton, M. P. (1975). The Philadelphia Geriatric Center moral scale: A revision. Journal of Gerontology, 30, 85–89.

Luo, L. (2008). Culture, self and subjective wellbeing: Cultural, psychological and social change perspectives. Psychologia, 51, 290–303.

Mathews, G., & Izquierdo, C. (2009b). Conclusion: Toward an anthropology of well-being. In G. Mathews & C. Izquierdo (Eds.), Pursuits of Happiness: Well-Being in Anthropological Perspective. Berghahn Books.

Matsyafed Information Guide. (2015). Government of Kerala.

Matsyafed Information Guide. (2012). Government of Kerala.

Ng, S. T., Tey, N. P., & Asadullah, M. N. (2017). What matters for life satisfaction among the oldest old? Evidence from China. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0171799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171799

Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2014). Residents of poor nations have a greater sense of meaning in life than residents of wealthy nations. Psychological Science, 25, 422–430.

Ovstegard, R., Kakumanu, K. R., Lakshmanan, A., & Ponnu Swamy, J. (2010). Gender and climate change adaptation in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh: A preliminary analysis. [Electronic resource] Tamil Nadu Agricultural University; International Pacific Research Centre, Hawaii (IPRC), [s.l.] ClimaRice.

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

Pullium, R. M. (1989). What makes good families: Predictors of family welfare in the Philippines. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 20, 47–66.

Raibley, J. R. (2012). Happiness is not well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(6), 1105–1129.

Ramachandran, B. B. (2021). An Anthropological Study of Marine Fishermen in Kerala: Anxieties. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Sen, A. (1985). Well-being, agency and freedom: The dewey lectures 1984. The Journal of Philosophy, 82(4), 169–221.

Shyam, S. S., Kripa, V., Zachariah, P. U., Mohan, A., Ambrose, T. V., & Rani, M. (2014). Vulnerability assessment of coastal fisher households in Kerala: A climate change perspective. Indian Journal of Fisheries, 61(4), 99–104.

Steel, P., Taras, V., Uggerslev, K., & Bosco, F. (2018). The happy culture: A theoretical, meta-analytic, and empirical review of the relationship between culture and wealth and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22, 128–169.

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 249–275.

Suh, E. M. (2000). Self, the hyphen between culture and subjective well-being. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and Subjective Well-Being (pp. 63–86). The MIT Press.

Sumagaysay. (2011, April 21–23). Adapting to climate change: The case study of woman fish driers of Tanuan, Leyte, Philippines. In Paper Presented at the 3rd Global Symposium on Gender and Fisheries, 9th Asian Fisheries and Aquaculture Forum, Shanghai, China.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). The concept of happiness. In Conditions of Happiness (pp. 12–38). Springer.

Veenhoven, R. (1996). The study of life satisfaction. In W. E. Saris, R. Veenhoven, A. C. Scherpenzeel, & B. Bunting (Eds.), A comparative study of Satisfaction with Life in Europe (pp. 11–48). Eotvos University Press.

Venes, D. (Ed.). (2001). Taber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary (19th ed.). F. A. Davis.

Sarvimaki, A. (2006). Well-being as being well—A Heideggerian look at well-being. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Health and Well-being 1(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v1i1.4903.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ramachandran, B.B. (2024). Subjective Wellbeing of Women in the Marine Fisherfolk of Kerala: Anthropological Insights on Life Experience, Attitude, and Life Satisfaction. In: Dev, S.M., Ganesh-Kumar, A., Pandey, V.L. (eds) Achieving Zero Hunger in India. India Studies in Business and Economics. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4413-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4413-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-4412-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-4413-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)