Abstract

Despite the socio-economic development, food insecurity and malnutrition are two evils found unexpectedly high around the globe hampering one of the most important human rights, the right to health. The conditions of health of people living in poverty are disproportionately worse than others. India’s obligation to ensure food security and health for all has its roots in International Law. Similarly, the country is also bound to provide these rights under the Constitution of India and the other national legal frameworks. However, India’s position in the recent Food Security Index, as well as Health Index, highlights the inadequacies in the nation’s obligation to guarantee the availability and accessibility of quality food to ensure physical well-being to all. This socio-legal research analysed the status of food insecurity in the State of Gujarat and its impact on urban poor living in the state. The study also has analysed the journey of ‘right to food’ as a fundamental human right under the Indian Legal system and the efficacy and success ratio of the Government initiatives with reference to Sustainable Development Goals. The study found that there is a huge gap in the system as the government schemes lack accessibility and as a result, the majority of the surveyed population are out of ration and also are not utilizing other government schemes for their benefits, hence leading a miserable life.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The World Summit 1996 proclaimed that ‘Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1996). Life Science Research Office (LSRO) has defined food security as ‘access to enough food for leading an active, healthy life’ (Committee on National Statistics, 2006). ‘Food insecurity exists whenever the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or the ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways are limited or uncertain’. Hence, we can say that food insecurity is ‘the limited and inadequate access to healthy and nutritious food which is sufficient to lead a healthy and productive life’.

The term food security implies mainly four points namely availability of food, accessibility of food, utilization, and stability (Nations, 2008). Availability of food implies enough food production, i.e. ample amount of food is being produced or imported to fulfil the need of the present without compromising the needs of future generations. The term accessibility simply denotes economic and physical access to food, which means that the financial incapability shouldn’t deprive people from accessing adequate food. Utilization means the effective consumption of the nutritious quality of the food to meet the dietary needs of the individual, it refers to feeding practices, food preparation, diversity of the diet, and intra-household distribution of food. Finally, stability means food security, i.e. the individual should have access to adequate food at all times (FAO, 2006). Food security analysts opine that there exist two major forms of food insecurity. It would be chronic food insecurity (long-lasting) if there is a deficiency in the bare minimum requirement of food grains to the vulnerable class for an ongoing period of time without any interruption, due to exertion, poverty, non-accessibility to financial sources, or other possessions. On the other hand, it would be termed as transitory food insecurity (short-term), when there is an unexpected loss of food or downfall in production process or plunge in accessibility to food, due to momentary fluctuations in food attainability or accessibility, in addition to annual fluctuation in domestic food production, cost of production and standard income. It shows that food security is quite a colossal and complex issue that is inherently tied to poverty, so much so that this strategic situation has been consistent for over a period of time. It is not food production that acts as a stumbling block, but rather the distribution of food that raises potent question against non-availability of food. For enumerating the share of food insecurity in each household, considering uncertainty, incompetency, and ineffective utilization or access to food, is deemed to be the standard method.

The roots of ‘Human Right to food’ can be traced to the ‘Universal Declaration on Human Rights 1948’, (UDHR, 1948). Under article 11 ‘The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ also recognizes right to food as part of an adequate standard of living and proclaims that every individual has a right to be free from hunger (International Covenant on Economic, Social & Cultural Rights, 1966). When we peep into Indian Legal System, India is a signatory to many of the above-mentioned International Instruments and hence there is an obligation on the country to ensure food security to its citizens. The Indian Constitution doesn’t have an express provision which guarantees the right to food to its citizens, however, there are certain indirect tacit provisions. Right to food is coherently interlinked with the concept of food security and the Constitution under Article 21 provides for the fundamental right to life which in its essence includes right to food also (Constitution of India, 1950). Further, the apex court once expressed ‘life is not mere animal existence (Francis Coralie Mullin Vs. Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi, 1981) but life with dignity’ (Maneka Gandhi versus Union Of India, 1978) and widened the scope of Article 21 to include all qualifying needs which are required to lead a dignified life. It is essential for an individual to get access to adequate food to lead a dignified life hence we can say that right to food is an inherent part of Article 21. The turning point in the event of ensuring food security in India can be said to be the Hon’ble Supreme Court’s decision in PUCL versus UoI and the subsequent implementation of the Food Security Act in 2013. Even after routing many programmes and policies aiming to pull out people from the curb of hunger, the country is still undergoing severe instances of hunger and food insecurity.

Food security for any country is vital as the same plays a major role in the country’s economic development. Non-accessibility to adequate food shall impair the enjoyment of other human rights such as right to health, education, and the fullest enjoyment of right to life. Food and health are having direct nexus with each other as nutritious food is an important factor in physical wellbeing. The food insecurity and hunger can bring in innumerable complications, the most significant being escalation in innumerable chronic afflictions like malnutrition, stunting, and wasting in children; anaemia; obesity; diabetes, deliberate protein and iron deficiency, etc., which has directly jeopardized the living standards of poor population residing in urban areas (Ke & Ford-Jones, 2015). Hence, we can say that food insecurity is leading to unhealthy population and adding to the disease burden of the country and this unhealthy population will not contribute to the development of the country. Iron deficiency, especially in connection with pregnant and lactating mothers and children, has endured as a public health concern (Tamura et al., 2002). Iron deficiency can even have a negative impact on the school-going children and this can lead to unbidden hesitation and circumspection and those children would fail to gain fewer opportunities from school that are essential for their primary development.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2021 ranked India 101th out of 116 participated countries is a matter of grave concern (Concern Worldwide; Welthungerhilfe, 2021). And the country ranked 71st by the Global Food Security Index, 2021 (Drishti IAS, 2021). Though the country has made some progresses since 2000 in both health and hunger-related indicators, still there exist issues in relation to accessibility of quality and nutritious food. India has made relative progress in indicators like malnutrition, stunting, IMR, MMR, etc., but is criticized for having the highest wasting rate of all countries participated in GHI (Concern Worldwide & Welthungerhilfe, 2021). Although there is a decrease in the GHI point of India from 38.8 in 2000 to 27.5 in 2021, still the level of hunger in the country is termed as serious. Malnutrition is a gross challenge which is contributing to the disease burden of the country. NFHS-5 reported despite Integrated Child Development Programme (ICDS) and Mid-day Meal, India continues to grapple with the issues of under-nutrition and stunting. One in every three children below the age of 5 years is reported to be underweight in India. As per the report the country has shown slight progress in stunting and underweight as the number of children under the age of 5yeas who are stunted has come down to 35.5% from 38.4% and number of underweight children from 35.8% to 32.1% (NFHS-5).

In addition to the aforementioned challenges, in India, majority of the urban poor population is reliant on the food distribution system for their improvised living standards. In spite of there being an elevated economic development in the last 30 years, there has not been sufficient improvement in the mechanisms functioning for the removal of hunger, insecurity, and malnourishment. Despite production and stockpiling of surplus food grains and products, there are starvation-related deaths reported in India even in this century. Shouldn’t starvation be regarded as a crime? It is the appropriate time to evaluate the developments undertaken and to interrogate if the efforts instigated thus far will help nation-states to achieve sustainable development goals. This research study was carried out to understand the current extent and severity of food insecurity faced by the urban poor in the state of Gujarat. The research team has also deliberated on the factors responsible for such perpetual situation. It is significant to explore the success ratio of governmental programmes aiming at the removal of hunger because if the attention is not paid to the present food consumption patterns by the urban poor, food security in Gujarat will never be restored.

2 Background

Food insecurity is quite a myriad concept that originated around six decades ago, a period when the world faced global food catastrophe. It is quite ponderous to put forward exact definition of the term ‘food insecurity’ (Maxwell & Frankernberger, 1992). World Bank report has stated it as; ‘when there is no access of all the individuals around the clock with adequate amount of food, required for a vigorous, dynamic and healthy life’ (Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1996). Poverty shares a strong nexus with food insecurity and has been the foremost reason behind prevailing hunger, malnourishment, starvation, low income, homelessness, racial and social inequality, discrimination, illiteracy, etc. India stands by as one of the leading nations having 17% of the hungry population which as per the Food and Agriculture Organization accounts for 195 million people (United Nations, n.d.).

The escalation in per capita income has failed to make any difference in the empty stomachs of 820 million people living on the globe and those in need are off the beaten track of food and nutrition so much so that the intermission between those having proper access to food and those facing the crises is increasing on an everyday basis (United Nations, 2019). On the other hand, with an increase in urbanization, a considerable growth in the population residing on roadside tents can be observed. India, being a constant producer of quality food grains has made a positive influence, thereby feeding hungry population residing on the streets but some hurdles in the last one decade, including shortage of rain, dry-spell, and other natural calamities in the central and southern regions have made an impact on feeding nutritive food to the entire population. A pivotal piece of information was laid down that it is also the weather or atmospheric pattern that acts as a deciding factor in the positive or negative outcome of the crops in the nations because of the consequential dependency of farmers on the rainy season for agriculture (Food & Agriculture Organization of United Nations, 2015).

The present pandemic situation has not only forced 830 million people to sleep with an empty stomach but around 3 billion people have also been the victims of several dispositions of hunger (Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2021). Around one-third of the food produced is either wasted or unused due to the prevailing financial constraints. Hence, hurdles pertaining to food production and distribution are not only extensive but also pitted in different spheres. On a regular note, category belonging to the rock-bottom socio-economic background or those who lack the political power tend to be the victims of food insecurity and hunger, they either be residing in the remote tribal areas or be settled in the marginalized sections of urban areas. The prevalence of disproportionate hunger and undernourishment in every arrangement is deeply embedded in imbalance and unevenness of socio-economic and political potentialities.

Due to several economic constraints and elevation in low-purchasing power, majority of urban poor cannot afford quality food and good standard of living. It has been put forward a several times that at majority wholesale markets, dealers who sell off their food products to the affluent class or upper-middle class, make choices of the food quality, such that it suits best to their standard of living while on the other end, stale food is supplied to poor urban residents. This approach makes a way ahead for bringing in food insecurity and getting around to set down their health standards. Food that lacks quality majorly comprises of expired products that are left over for decomposition. To quite not a surprise, such inhuman treatment has been practiced for over a long period of time because consumption of balanced and nutritive food has never been a matter of precedence in urban poor households. Following such practice would be nothing but just an addition to their diet.

In the year 2016, the Sustainable development goals set forward by the United Nations were taken into consideration to conduct some efforts over the coming decenniums to put an end to every semblance of existing poverty, hunger, inequality, geographical and climate modifications, while certifying that none, either from rural or urban areas are left behind. Even the second SDGs made an effort towards achieving ‘end to poverty and hunger’ slogan, thereby achieving adequate food security and competent nutritional scale that can help in sustaining agriculture. However, it has failed to call attention to various courses of actions in which several clusters have been the victims of malnourishment. The SDGs 10 on the other hand have laid down their absolute focus on socio-economic, political, and health imbalance, but has however made no speculation about hunger, under-nutrition, starvation, and malnutrition, even though there exist the groups who have turned out to be the consistent assailants of starvation, poverty, deficiencies, polyphagia, obesity, and high blood pressure.

At this point of time, the world is moving ahead at quite a different pace as compared to where it was a decade ago, carrying a positive notion to put an end to hunger, food insecurity, poverty, under-nutrition, and malnourishment. There was a wave of optimism that such reformative and cathartic approach would result in the acceleration of laidback approach adopted in the past and put this globe, back on track to pull off the reasonable target. The studies conducted on this subject matter reveal that this world has not moved ahead towards the path of achieving and ensuring access to nutritive, abundant, healthy food for vulnerable population, around the year. Politics, rivalries, climate, changeability, mutability, antithesis, economic backdrop, and failures act as the major drivers in slacking down the efficiency, especially when inconsistency and variation are high.

3 Methods and Practices

This study was conducted in the urban areas of Gujarat state to understand the current extent and severity of food insecurity and hunger on health of the people in the state. The authors adopted a multi-method approach in this study, which comes to light as a combination of both doctrinal and empirical methodology. To understand the status of right to food in India, global and Indian status of hunger, food insecurity, malnutrition and its impact on health, the authors have looked into the primary authoritative sources like international covenants, conventions, declarations, the Constitution of India, Legislations and the Judicial Pronouncements, and the secondary sources like reports of international and national organizations, websites of United Nations Organizations, Government of India and Government of Gujarat, Articles published in reputed journals, reports of NGOs and other organizations working on the same subject area, coupled with an assessment of the present ground reality existing in the State of Gujarat. This study was conducted in five districts of Gujarat, namely, Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar, Vadodara, Surat, and Rajkot. To collect the data from the primary target group, the ‘urban poor’, the authors have adopted a survey method. Data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire.

4 Findings and Discussion

The research team in the current study has placed under cover the severity of food insecurity faced by the urban poor in the state of Gujarat and to also understand the impact of food insecurity on nutrition status and health of the urban poor. In the initial stage, the team relied on a doctrinal survey of various International, National, and Regional legislations, judgements, articles, reports, etc., to unveil and understand the various aspects involving food security and hunger. The findings of the secondary analysis are as follows.

4.1 Legal Spectrum Regulating Food Insecurity and Hunger

Food and nutrition being the undermining determinants of health is of great importance both internationally and nationally. India’s obligation to ensure food security for all arises from both International Law as well as National Legal frameworks. This obligation can be categorized as obligation under:

-

1.

International Law

-

2.

National Legislations

-

3.

Constitution of India

-

4.

Judicial Pronouncements

-

5.

Obligation of a Welfare State

-

6.

Right-based Approach.

Right to food is a complex concept and it cannot be discussed in isolation. Access to adequate food is a prerequisite for the fullest enjoyment of life, it is essential to maintain good health too. The first ever document to recognize human right to food is the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) 1948. The declaration under Article 25 declares that ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food’ (Organisation & UNDP, 1948). Subsequent to UDHR, the International Covenant of Economic, Social & Cultural Rights, 1966 under article 11(1) reaffirmed the right of individuals to adequate standard of living and under article 11(2) the Covenant provides for ‘individuals right to be free from hunger’. The Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights under General Comments 12 has mentioned that ‘the right to adequate food is indivisibly linked to the inherent dignity of the human person and is indispensable for the fulfilment of other human rights enshrined in the International Bill of Human Rights. It is also inseparable from social justice, requiring the adoption of appropriate economic, environmental and social policies, at both the national and international levels, oriented to the eradication of poverty and the fulfilment of all human rights for all’ (Committee on Economic, n.d.). Around the world, it is women, children, and other vulnerable sections like disabled, migrants, etc., are the most disadvantaged group who is deprived of access to adequate food. This is evident from the health Index that these categories are suffering from malnutrition, anaemia, and other health issues. As a response, the international community has given special attention to these vulnerable categories by addressing their basic rights through special instruments, which include the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women 1979, the Convention on Rights of Child 1989, and the Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006. These instruments recognize the right to food of women, children, and disabled people, respectively. In addition to this, there are a number of binding and non-binding instruments developed regionally and internationally to provide for access to food.

In India, the Constitution does not provide for the fundamental right to food; however, it has been recognized as a right within the ambit of Article 21 which provides of ‘right to life and personal liberty’. Under Article 21, the Constitution mandates the state to protect life with dignity. To understand the state obligation under the Directive Principles of State Policy towards right to food, the Articles 39 (a) and 47 should be read with Article 21. Under Article 39(a), the Constitution directs the state to make policies to attain an adequate standard of living for its citizens and under 47 to take steps to raise the level of nutrition and standard of living of the people (Jain, 2018). The preamble to the Constitution provides for socio-economic justice and in addition to that the Constitution establishes the country as a welfare state, the primary obligation of the welfare state is the welfare of its people and without achieving universal access to food, social justice cannot be achieved.

The role played by the judiciary in recognizing the ‘right to food’ is commendable. In 1989, the Hon’ble Supreme Court considered a letter from two social workers highlighting the miserable conditions of people living in the Kalahandi district of Orissa on account of extreme poverty as a writ petition. Directed the Government of Orissa to take adequate social welfare measures and prompt actions to curb the starvation deaths happening in Kalahandi district (Kishen Pattnayak & Anr versus State Of Orissa, 1989), Food clothing and shelter are the basic human rights (M/S. Shantistar Builders versus Narayan Khimalal Totame, 1990). Right to life guaranteed by a civil society should include right to food, clothing, descent environment, and a reasonable accommodation to live in (Chameli Singh And Others Etc. versus State Of U.P. And Another, 1995).

In PUCL Vs. UoI, Court established a constitutional human right to food and created a basic nutritional floor for India’s underprivileged millions. This judgement marked a watershed in the history of right to food in India. The People's Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) filed a ‘writ petition’ before the Supreme Court on the right to food in April 2001. This petition was filed at a time when the country's food reserves were at an all-time high and hunger in drought-stricken areas was also on the higher side. The government of India, the Food Corporation of India (FCI), and six state governments were slammed by the apex court on grounds of inadequate drought relief. This case became one of the breakthrough judgements on chronic hunger and malnutrition. The case highlighted the failure of government in two aspects namely the collapse of the public distribution system (PDS) and the inadequacy of drought relief efforts. The judgement addressed a wide range of issues involving right to food such as execution of food-related projects, urban poverty, the right to work, starvation deaths, and general transparency and accountability concerns (People’s Union Of Civil Liberties … versus Union Of India (Uoi) And Anr., 1996).

The Supreme Court gave the first major interim order which focuses on eight food-related programmes, namely, the ‘Public Distribution System (PDS); the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY); the National Program of Nutritional Support to Primary Education, also known as the mid-day meal scheme; the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS); Annapurna; the National Old Age Pension Scheme (NOAPS); the National Maternity Benefit Scheme (NMBS); and the National Family Benefit Scheme (NFBS (NFBS)’. The interim order of November 28, 2001, essentially changed the advantages of these eight schemes into legal privileges. This means that if someone has an Antyodaya card but isn’t getting her full monthly quote of 35 kg of grain at official pricing (Rs 3/kg for rice and Rs 2/kg for wheat), she has the right to sue for what she’s owed, even if it means going to court. The administration was also ordered to replace monthly dry rations of grain with daily, cooked mid-day meals. In addition to the aforementioned the court ordered the government to finish the identification of BPL categories and start providing them with ration cards and 25 kg of grains per family per month; to ensure accessibility to ration stores and regular grain supply; to make the dealer and shopkeeper accountable for their actions denying access to ration to the eligible candidates; Awareness to BPL families about their entitlements, etc. (People’s Union Of Civil Liberties … versus Union Of India (Uoi) And Anr., 1996).

Another development after this judgement was the implementation of the National Food Security Act 2013 by the country. The act provides for the food and nutritional security of the public in human life cycle approach. As per the act the government is under an obligation to provide food entitlement to 75% of the rural India and 50% of the urban population; the eligible household can claim 5kgs of food grains/person/month; the entitlement under the Antyodaya Anna Yojana shall be 35ks per household; age-appropriate food to be issued by anganwadi’s and under mid-day-meal to children. In addition, the act suggested the constitution of the State Food Commission to monitor and evaluate the implementation of the scheme and suggested PDS reforms both at state and central levels (The National Food Security Act, 2013).

Even after all these instructions by the apex court, another incident which spooked the conscience of the country occurred in 2017 in Jharkhand. A writ petition was filed by HRLN for the mother and sister of Santoshi, an 11-year-old girl from Simdega, Karimati who lost her life due to starvation on September 28, 2017, before the Apex court of India, and that the petition clearly instigated the hurdles faced by millions of people who fail to receive benefits of ration card due to Aadhar card-related complications. In particular, it addressed how death of the victim shared a direct nexus with denial to providing her a ration card since she belonged to the Dalit community and her ration card was not linked with Aadhaar card. The petition had drawn attention to the interconnection of food security schemes that were put together for poor population with Aadhar card as a binding element and how it could have the most ravaging impact on their health and well-being. It is therefore, the need of the hour, to look into the cases of food insecurity that repudiates the life of an individual and to make sure that nothing interferes with the elicit distribution of food and other prerogatives that are meant for the poor population. It was pleased that the Court must hold on to the responsibility to guarantee that no sanctioned person is dissented from receiving subsidized food grains under the respected schemes for unavailability of Aadhaar card. Other than this, it was also requested that the court must surpass the order to the authorities to put hold on the mandatory usage of Adhaar card-based biometric authentication methodology to dispense food products and other essentials (Koili Devi versus Union Of India, 2019).

The role played by the Government of India in increasing food production and combating food insecurity is notable. The government activities intending to curb the challenges thrown by food insecurity can be classified under various heads, namely, (i) Initiatives to boost Agriculture production; (ii) Initiatives to control food price; (iii) Initiatives to create employment opportunities, poverty reduction, and economic growth; (iv) Initiatives to improve the public healthcare system; and (v) Initiatives to improve education and human development. In addition to that India has always put its hand forward in affiliating itself with food security organizations and programmes conducted by them on a regular basis. One of the notable steps by the Government of India (GoI) intending to boost the farming was integration of technology into agriculture. Some notable government programmes to support farming includes the National Food Security Mission; Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana; Integrated schemes on pulses, palm oil, oilseeds, and maize; Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bhima Yojna; e-market; Massive Irrigation and Soil and Water Harvesting Programme, etc. These programmes have helped the country to move away from dependence on food aid to become a food exporter. As a step towards mitigating and removing the impacts of food insecurity on the health of the people, the government introduced Public Distribution Systems for distribution of food grains to vulnerable sections of the society at an affordable rate. To take care of the malnutrition issues in children the government introduced mid-day meals at schools and under this scheme the children are given access to wholesome freshly cooked lunch. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare through Anganwdi’s distribute ration, health powders, and supplements to pregnant women and children.

The Constitution under Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) declares India as a Welfare State and as per this the state plays a vital role in ensuring the socio-economic development of the people. A welfare state aims at creating economic equality and ensuring equitable standard of living to its citizens. The provisions laid down in the DPSP are though not enforceable but they are fundamental to the governance of the country. Hence, being a welfare state guaranteeing access to adequate food and proper health are the obligation of our country.

In addition to this United Nations has adopted the ‘Human Right Based Approach’ (HRBA) as the key principle for the UN Common Country Programmes. Prior to this UN had ‘Basic Need Approach’ before 1997 in which they identified the basic requirements of the beneficiaries and the policies and programmes were made to address the same (United Nations Population Fund, n.d.). Whereas in the case of HRBA, the duty bearers develop their capacity to encourage the right holders to claim their rights. secondly to strengthen the capacity of duty-bearers who have the obligation to respect, protect, promote, and fulfil human rights (Why a Human Rights-Based Approach?, n.d.). Human Right-Based Approach is based on ‘Participation, Accountability, Non-discrimination and Equality, Empowerment and Legality’ (European Network of National Human Right Institutions, n.d.). The right-based approach is capable of guaranteeing the human right required to attain the food security. This approach addresses the deprivation of basic needs and any other interventions which are root causes of hunger and food insecurity.

4.2 Findings of Field Investigation Conducted in the State of Gujarat

Gujarat ranks in 4th position in the list of most urbanized states in India, as reflected by Census data 2011 (Sivakumar, 2011). It shows that the state is one of those economies that has achieved growth and development at an accelerated rate, surpassing the domestic scale for almost four decades. However, the economy has observed imbalance, and it is the most prominent issue that has made a detrimental effect on the state’s burgeoning path. Statistics laid down by planning commission encapsulates the prominence of poverty in the state that has a direct effect on the purchasing power of majority of population. NITI Aayog has reported that 18% of the population in Gujarat lives below poverty line and the reason behind such poverty is their employment only in informal and colloquial sectors (Aayog, 2021).

It goes back to the year 2013 when the Government of Gujarat made history of not implementing the schemes that were significant for increasing the magnitude of food security. There was criticism towards the central government for repudiating the procedure of taking states into confidence and pre-determining the population of macro-beneficiaries. The most accurate reason behind vulnerability in the state of Gujarat is its susceptibility to disasters like drought, flood, earthquake, and other calamities. This has nothing but a direct impact on the mass production of food grains, thereby leading to dissipation of livestock, loss of human productivity, and other significant assets that would ultimately run a deep impact on the state economy. The schemes formulated for the vulnerable class are in need of formalized discussion since they are the ‘lived realities’ of innumerable people who are in grief for over a long period.

As per the data provided by International Food Policy Research reports, Gujarat still encounters food insecurity at a scale which makes it a gravely food self-effacing state. It demands nothing but auxiliary improvisation in the schemes and strategies formulated for uplifting the nutritional values and dietary intake of women and children in the state. In spite of there being an escalation in multiple health indicators and ethical indices, the level of food insecurity encompasses over 1% in the nation. The state government, together with public departments and organizations, has put forward its interest to resolve the prevailing hurdle by seeking assistance from experts, organizations, consultancies, and public servants at the grass-root level. The State Government, through Swarnim Gujarat goals, somehow have set the priorities to lean on the agendas designed to diffuse the complications created by food insecurity and reduce the level of under-nutrition, peculiarly among pregnant women, adolescents, and children below 5 years of age, noting that they receive an optimum amount of care and attention.

Even when a research study was conducted by M. S. Swami Nathan Research Foundation (2013, 2014), they handed down 16 significant factors for the urban patch and came down to the conclusion that Gujarat among all the states in India can be termed as ‘severely insecure’. This illustrates the primary concern that fault impugns over accessibility and not over the production of food grains. Technically, in the past, glitches with regard to public distribution system had acted as a major obstacle for the vulnerable population. Other than this, inability and laidback approach of the fair prices shops has further emanated into taking off an opportunity from the poor communities to have access to food grains.

The current status of Gujarat is alarming as the state is facing huge challenges of malnutrition as per the NFHS data. Table 1 shows that in all pointers, namely, stunting, wasting, underweight, and overweight, there is increase in the percentage of the total cases as compared to NFHS-4 data.

Hence, it can be said that there is no rampant advancement in undertaking obligations and financing to the health system or nutrition cycles which ultimately is affecting the strenuous cycle of achieving sustainable development goals. There also seems to be a gap in the appropriate projection of the population that requires an immediate action to fill the food accessibility gaps and thereby save their lives. It is high time that the State bodies now must streamline policies for targeting all issues which have an impact on malnutrition indicators, deploying IEC and SBCC tools for education and sensitization of the vulnerable sections towards their nutritional health and the inclusion of nutrition and food security within the ambit of universal health coverage for the attainment of better health outcomes amongst the entire population of the state.

The current study has examined and explored the issues and challenges concerning food and nutrition security of the urban poor in Gujarat. The situation in the major cities in Gujarat was studied by surveying the same through a questionnaire.

4.2.1 Personal Profile of the Respondents

In the present study, the research team considered different age groups for the study. Out of 400 total respondents, the majority belonged to the age group 19–35 years followed by 30–60 years. About 1.0% fall in the 0–6 years’ age group, 14.5% fall in the 7–18 years’ age group, 53.1% of the respondents in the 19–35 years’ age group, 23.6% and 7.8% fall in the 36–60 years and 61 years and above age groups, respectively. And 34% of the respondents were males and majority that is 66% were females.

Of the total female respondents, 12.09% are ‘pregnant’, 11.29% are ‘adolescent’, 18.14% are ‘lactating women’, and majority that is 58.46% belong to ‘other’ category. One of the major facts identified by the researchers from ground is that considerable percentage of family surveyed are having more than four children and majority of the above-mentioned pregnant ladies are pregnant with their fourth or fifth child.

Majority of the surveyed population were migrants, either interstate or intrastate migrants. The study had 62.75% of the respondents having Domicile in Gujarat and out of which 49% belong to various parts of Gujarat including the tribal region. 11.5% belonged to Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh (11.5%), Uttar Pradesh (7.25%), and Bihar (3%) among others in a decreasing order. There were very less migrants from states like Andhra Pradesh, Punjab, West Bengal, and Haryana.

From the surveyed population, 55.50% are daily wage workers and 35.75% were not working only 8.75% of respondents are either salary earning, beggars, household workers, self-employed, or students.

4.2.2 Household Profile

It has been found in the study that majority of respondents have more than two family members of which 18.5% were having five family members and 25.75% were having six family members. 85.75% of the respondents were having less than four kids in their family followed by 10.5% having 4 kids in their family and the rest with more than 4 and up to 10.

Majority of the respondents, i.e. 81% were not in possession of land and only 19% agreed that they possess their own land in their respective state or region. The data reflected that only 14% of the surveyed population is having their own house at their place of origin, whereas majority (86%) were homeless. And 59.25% of the surveyed population were living in temporary houses such as tents or other arrangements on pavements. Three per cent of the respondents live in dwellings that are designed to be solid and permanent (Pukka House) and 37.75% live in kutcha houses or houses made with un-burnt bricks, bamboos, mud, grass, reeds, thatch, loosely packed stones, etc.

Figure 1 demonstrates that out of the total surveyed respondents 62.75% are earning between 4166 and 8334 as monthly income followed by 18.5% of the respondents earning RS. 20,000–50,000 annually. 12.75% is earning between 1 and 2 lakhs; 3.5% earning 2 lakhs and above and only 2.5% earning 20,000 annually. The data set shows that majority of the respondents who earn the least are daily wage workers.

As shown in the above Figs. 2 and 3, only 70% of the total participants, i.e. 279 respondents were having ration card. Out of 279 respondents, 61% were having BPLFootnote 1 category card, 13% with each having AAYFootnote 2 and PHHFootnote 3 followed by 12% of the respondents holding APL-1 category and 1% holding APL-2 category ration card.Footnote 4

4.2.3 Current Extent and Severity of Food Insecurity Faced by the Urban Poor in the State of Gujarat

The question on the consumption of food in a day received a mixed opinion. As mentioned in Table 2, majority of the respondents including their family members consumed food two times per day. Maximum respondents didn’t respond to the question on consumption of food by their other family members (356), father (306), mother (286), wife (47), and children (58). The reasons for going unanswered are mainly two; (i) is that they were not having that family member; and (ii) that family member is not staying with them as they have migrated to urban areas of Gujarat for work either from other districts of Gujarat or from outside Gujarat. The table represents that most of the people in the above categories either consume food twice a day or three times a day and none of the respondents or their family members are consuming food based on the hunger (Tables 3 and 4).

During the field study, it has been found that the respondents don’t consume what they should and some of them are (77.75%) not even able to fulfil the needs of their children when it comes to choice of food. There is a lack of variety, every day they consume the same items. During the field study, 89% of the respondents expressed that they are not able to access the food of their/families’ choice due to financial constraints, whereas 11% answered against the majority opinion (Fig. 4).

The above-mentioned problems due to financial constraints are faced by most of the respondents almost equally. Majority of the respondents ranging between 98 and 98.5% agreed that they worry about exhausting the food grains, they eat same food for days as there is no money to purchase variety, and they compromise on the quantity of the food to feed other members of the family and few agree that they often starve.

Table 5 illustrates that majority of the respondents faced problem in accessing food. For every given situation, 97–97.5% of the respondents agreed. This may be due to the prevailing COVID situation also as the data is collected during the COVID lockdown.

In our survey, it has been found that majority of the urban poor (as per our operational definition) are migrants either from within the state or outside the state. Many of them are out of Public Distribution System as they belong to different regions of the state or the country. Hence, they are spending a considerable amount of their family income in purchasing food. Figure 5 depicts that majority (61.5%) of the respondents are spending RS. 4000/- and above to purchase food per month followed by 22.25% spending RS. 3000–4000/-, 8% each spending RS. 2000–3000/- and RS. 1000–2000/-, and only 1.25% spending up to Rs.1000/- or not spending anything on purchase of food.

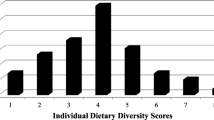

Table 6 illustrates that majority of the respondents have regularly included cereals (66.3%), vegetables (75.8%) and milk (52.25%) in their diet or otherwise their access is only limited to the aforementioned three food items. The study found that majority of the respondents don’t consume meat (67%) and egg (65.5%). Not consuming non-vegetarian food is highlighted as one of the reasons for the malnutrition by the experts during the Focus Group Discussion too.

As given in Fig. 6 the field investigation found that the respondents were facing difficulty in accessing food other than economic inefficiency and non-availability of food. Sixty-four per cent of such reasons accounted for unemployment, 30% faced challenges as they were not having ration card, and 6% of them quoted pandemic as one of the reasons adding to their struggle (Table 7).

It has been found in the study that during crisis majorly the urban poor are dependent on the neighbours for getting food (33.60%), some of them go to other public other than neighbours for assistance (30.16%), a few prefer to starve (21.83%), and very less take the assistance of government and NGO’s, 8.60 and 5.82%, respectively.

As per the findings as depicted by Table 8 74.25% of the respondents agreed that they have starved at least one day during the month of data collection. 47% of the total respondents have starved at least for 2 days followed by 29% up to 3 days. Only 9% of them reported that they have starved for more than 4 days also (Table 9).

As per the data, 18.75% of the respondents or their children were having issues of malnutrition. 62.75% did not have any issues of malnutrition. 16.75% were diagnosed with stunting, 10.5% with wasting, and 23.25% underweight.

Table 10 demonstrates that 21.75% of the respondents or their family members were anaemic; 28% of the households reported to have experienced IMR and 5.75% MMR. IMR and MMR were very less reported by the respondents in their households (Table 11).

As per the study, only 27.5% of the participants prefer to visit hospitals in case of illness and majority 72.5% were not visiting and are not ready to visit hospitals in case of diseases (Table 12).

As per the response given by the respondent’s majority of the respondents (70.75%) are not availing of the schemes on health care initiated by the government to support the poor. Only 29.25% of participants responded positively that they are availing benefits under the government schemes for health care (Fig. 7).

Gujarat Nutrition Programme, Anemia Mukt Bharat or Intensified National Iron Plus Initiative (I-NIPI), Immunization programme, Supplementary nutrition, Health check-up, Referral services, Pre-school education (Non-Formal), Nutrition and Health information, Contraceptive counselling for adolescents, Gujarat Poshan Abhiyan 2020–22, Gujarat Anna Bramha Yojna, Annapurna, Mid-day Meal at Schools, Free Ration through Public Distribution System under National Food Security Act, Antiyodaya Anna Yojna, Kishori Shakti Yojana, Kasturba Poshan Sahay Yojana, Indira Gandhi Matrutva Sahyoj Yojana are some of the programmes implemented in Gujarat aiming to alleviate hunger, ensure health care and nutrition. The study found that a very negligible number of respondents are having awareness on these programmes. Some of the respondents know about mid-day meal (53.5%) programme and the free ration schemes rest of the schemes have not reached the urban poor yet (Fig. 8).

As there is less awareness, the respondents are not availing or a minority of the respondents are availing the government schemes. Majority 44.25% of the respondents are availing benefits under the mid-day meal scheme. Other than that 24.75% of the people are aware of the free ration schemes. Despite some big strides by the intervention of the Supreme Court of India through its interim orders that allowed these schemes to move forward in a crucial manner, the availing of these schemes in this survey was very dismal.

The biggest gain in respect of food insecurity has come from the mid-day meal scheme, which was also the most availed scheme when surveyed. The revision in guidelines in 2004 and 2006 has really reinforced this scheme and the impact it has on food insecurity in India. An extension of this scheme to cover children up to class X would be highly recommended. Given the fact that this scheme has already been well-received and is known to many. Apart from this, a substantial need was felt to improve the hygiene and sanitation needs, when surveyed this was the most required need by the urban poor in terms of what they want the government to act on. Further, local bodies should encourage to go on drives to actively involve and inform the people about the existing schemes and procedures to avail them. Migrant workers make up a large chunk of the urban poor in these cities and language and literacy barriers in availing the schemes should also be addressed.

Table 13 demonstrates that 92.75% of the respondents were of the opinion that they are facing many barriers in getting access to and availing the benefits under government schemes. It has been observed from the ground that majority of the urban poor are illiterates and, for them, it is difficult to understand and apply for the schemes too. Only 22.75% of the respondents think that all the schemes put forward by the government are useful or capable of yielding benefit, whereas 76.25% are of the opinion that the schemes are not useful to them (Table 14).

5 Conclusion and Suggestions

After the analysis, it has been found that what is being delivered by the government is just a comprehensive action which unfortunately has failed to take charge of issues faced by the urban poor because the entire focus is on the rural-based population. Systematic food distribution system is extensively regarded as the most fitting approach for the system to cope with the escalating challenges like food insecurity and hunger, poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, gender inequality, and shortage of apposite measuring tools. However, there is absolutely no solution that can be suitable for every circumstance but a reasonable interference can be attuned to the prevailing situation, including appropriate food accessibility and convenience, in addition to the prolonged development projections. The approach admitted must be suitable and deal with the elements of food insecurity, alongside the indispensable political adhesion to attain the required success.

The study recorded that majority of the urban poor are leading a miserable life and many have lost hope and they feel that it is a lost cause to expect anything from the government. As mentioned above very less schemes are accessible to these vulnerable sections. As the majority among the surveyed category of respondents were migrant workers, they were out of reach of access to free ration schemes as well. Even when it comes to distribution of food, due to several economic constraints and elevation in low-purchasing power, majority of urban poor can afford nothing but food of cheap quality and a mediocre lifestyle. In addition to the same they undergo other challenges like unavailability of clean drinking water, shelter, clothing, quality education, health care, and many other basic needs. They are not aware of the government schemes aiming to uplift them and hence are not availing the same. Another significant factor influencing food production and consumption pattern is socio-economic discrimination. The research team has observed certain practices of discrimination practised within the respondents’ group.

The other pre-eminent feature responsible for food insecurity is the high frequency of force majeure. Majority areas in the state of Gujarat are prone to droughts, leaving them captivated under the trap of food insecurity and hunger. On the other hand, increase in population, enjoining increased demand for water supply and agricultural land, has left a coercive effect on the frail resource system in the majority parts of the state of Gujarat. Infrastructure is considered as the pivotal feature for the development of any economy, however progressive it is. The Government of Gujarat has made efforts towards implementing schemes that can provide direct access to food to the vulnerable section, still there is no proper promulgation of relief and support to people.

It is an alarming finding that majority of the respondents and their family members consume food only twice a day. Almost 90% of them agree that they consume less food than they should and are unable to feed their children enough food due to lack of money to buy the same. An overwhelming majority of the respondents (98%) live in constant worry about their food running out before they can afford more. They lack access to variety in food as they can only afford limited types of foods on which they could rely on to feed their family. Due to financial constraints, the urban poor eat less than they should, and as a result, they are often hungry. In times of food crisis, especially during the lockdown due to the COVID pandemic, less than 10% of the respondents turn to the government for assistance. Almost half of the respondents (47%) have gone without food for 2 days. This is a matter of grave concern and reflects the high levels of food insecurity faced by the respondents.

Another matter of concern is that the data further shows that the majority of the schemes and initiatives set in place by the government go underutilized. Respondents felt that there are many barriers in availing the benefits under the above-mentioned schemes. This could range from red-tapism to corruption and needs to be addressed in order for these schemes and initiatives to actually make a difference. This is further supported by the fact that when facing problems in availing the benefits under the schemes the respondents usually have no one to contact.

A few measures which can be adopted to improve the condition of the urban poor in terms of guaranteeing food security can be;

-

1.

Steps to Improve the Current Welfare Programmes/Schemes

The study found that among the ‘urban poor’ majority fall into interstate or intrastate migrants. The very first step the government needs to adopt is to take necessary steps to expand the coverage of existing welfare schemes to include migrant workers too. For the same, the state government should maintain a registry with the details of migrant population residing in their state. Universalization of schemes on basic rights also can be a solution. The implementation of ‘One Nation One Ration Card Yojana’ needs to be expedited, so that the current conditions and issues of non-access to ration schemes can be eliminated. Adequate number of awareness programmes on government schemes for urban poor needs to be initiated to spread awareness on the programmes and also educate the urban poor about the formalities to be furnished to avail such benefits. Adoption of right based approach to food and community participation in implementation of schemes might help in bridging the gap in the implementation of the welfare programmes.

-

2.

Administrative Measures

More decentralized approach is required. The local authorities should be entrusted with more responsibilities in relation to the implementation of the welfare schemes on food, nutrition, and health care. The local self-governments should be supported with more financial assistance for the effective implementation of the schemes. Periodic monitoring of the schemes and revision of schemes as per the requirement can be done with the help of involvement of various agencies, academic/research institutes, and civil society. A nodal agency with representation of officers of the Department of Social Justice, the Department of Health and Family Welfare, the Department of Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs, the Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Women and Child Welfare is required to ensure the collaborative work. Regional offices should be set up to provide information and assistance to public in availing the benefits under the government schemes.

-

3.

Some Other Measures

-

a.

The slabs classified for the below-poverty line people should be re-modelled considering the present income earning capacities and include other indicators like housing and land ownership, especially for the migrated urban population.

-

b.

As discussed in the chapter food security is a complex issue and it cannot be discussed in isolation with other rights. Education plays a vital role in improving the standard of living of the public. Educated people may effectively utilize the accessed food. Hence, schemes on literacy, compulsory education for children and adult education need to be implemented effectively.

-

c.

Encouraging the practice of urban kitchen gardens for growing vegetables for self-sustenance by teaching the urban poor (those who are having their own land) to utilize their land for growing food, instituting social safety nets like the establishment of community kitchens, urban farmer’s markets, urban food stores/banks, and self-help group co-operatives that help in the cementing of an urban agricultural programme while also involving beneficiaries in its functioning through the practice of social audits to foster a participatory approach.

-

d.

PDS and be innovative in our supply chain and monitoring of supply chain. Since the studies are highlighting the deficiency of micro-nutrients, the Public Distribution System (PDS) should provide perishable micro-nutrient-rich food also as part of ration to the urban poor.

-

e.

Adopting developed nations’ model of giving food/grocery coupons instead of distributing ration through designated centres shall help in removing corruption and also the beneficiaries will get more varieties to choose.

-

a.

Notes

- 1.

BPL is a card under Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS). The beneficiaries holding this card receive 10–20 kg food grains per family per month at 50% of economic cost.

- 2.

“Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) and Priority Household (PHH) are two types of ration card provided under NFSA. AAY is provided to impoverished families identified by the state governments specifically to people without stable income. The eligible people under this category include unemployed people, women and old aged people. Under this scheme they receive 35kg of food grains per month per family and food grains at the subsidized price of Rs.3 for rice, Rs.2 for wheat and Rs.1 for coarse grains”.

- 3.

“Families not covered under AAY are covered under PHH. The state governments identify priority household families under the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) as per the guideline. 5kg of food grains per person per month and Food grains at the subsidised price (Rs.3 for rice, Rs.2 for wheat and Rs.1 for coarse grains) are provided to the PHH cardholders”.

- 4.

“APL families receive 10–20kg food grains per family per month at 100% of economic cost”.

References

Aayog, N. (2021). National multidimensional poverty index baseline report.

Barrett, C. B., & Lentz, E. C. (2021, February). Food insecurity. In International Studies Compendium Project (pp. 170–175). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350080454.ch-009.

Chameli Singh and Others Etc. versus State of U.P. and Another. (1995). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/64823282/.

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (n.d.). General comment No. 12: The right to adequate food (art. 11).

Committee on National Statistics. (2006). Measurement of food insecurity and hunger and hunger in the United States. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11578.html.

Concern Worldwide; Welthungerhilfe. (2021). Global hunger index 2021. https://www.globalhungerindex.org/ranking.html.

Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe. (2021). India—Global Hunger Index (GHI). https://www.globalhungerindex.org/india.html.

Constitution of India. (1950). https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-of-india.

Drishti IAS. (2021). Global food security index 2021.

FAO. (2006). Policy brief changing policy concepts of food security. http://www.foodsecinfoaction.org/.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (1996, November). World food summit—Final report—Part 1. FAO. https://www.fao.org/3/w3548e/w3548e00.htm.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2021). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021. https://doi.org/10.4060/CB4474EN.

Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations. (2015). Climate change and food security: risks and responses.

Francis Coralie Mullin Versus Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi. (1981). https://www.scconline.com.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (1966). https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx.

Jain, M. P. (2018). Indian constitutional law (8th ed.). Lexis Nesis.

Ke, J., & Ford-Jones, E. L. (2015). Food insecurity and hunger: A review of the effects on children’s health and behaviour. Paediatrics & Child Health, 20(2), 89. https://doi.org/10.1093/PCH/20.2.89.

Kishen Pattnayak & Anr versus State of Orissa. (1989). https://www.unhcr.org/publications/manuals/4d9352319/unhcr-protection-training-manual-european-border-entry-officials-2-legal.html?query=excom1989.

Koili Devi versus Union of India. (2019). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/91179340/.

Maneka Gandhi versus Union Of India. (1978).

Maxwell, S., & Frankernberger, T. R. (1992). Household food security: Concepts, indicators, measurements. Techinical Review, 280.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Government of India. (n.d.). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–2021. Retrieved January 19, 2022, from http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-5.shtml.

M/S. Shantistar Builders versus Narayan Khimalal Totame. (1990).

People’S Union of Civil Liberties ... versus Union of India (Uoi) and Anr., (1996). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/31276692/.

Saxena, N. C. (n.d.). Hunger, under-nutrition and food security in India. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08ac540f0b652dd0008cc/CPRC-IIPA44.pdf.

Sivakumar, B. (2011). Census 2011: Tamil Nadu 3rd most urbanised state. Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/census-2011-tamil-nadu-3rd-most-urbanised-state/articleshow/9292380.cms.

Tamura, T., Goldenberg, R. L., Hou, J., Johnston, K. E., Cliver, S. P., Ramey, S. L., & Nelson, K. G. (2002). Cord serum ferritin concentrations and mental and psychomotor development of children at five years of age. The Journal of Pediatrics, 140(2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1067/MPD.2002.120688.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2008). An introduction to the basic concepts of food security. In EC-FAO Food Security Programme. www.foodsec.org/docs/concepts_guide.pd.

The National Food Security Act. (2013). The gazette of India 18. http://indiacode.nic.in/acts-in-pdf/202013.pdf.

United Nations. (n.d.). Nutrition and food security. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from https://in.one.un.org/un-priority-areas-in-india/nutrition-and-food-security/.

United Nations. (2019). Over 820 million people suffering from hunger; new UN report reveals stubborn realities of ‘immense’ global challenge. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/07/1042411.

UN Organisation, & UNDP. (1948). Universal declaration on human rights 1948. https://www.un.org/en/udhrbook/pdf/udhr_booklet_en_web.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shanthakumar, S., Dhanya, S. (2024). Socio-legal Analysis of the Impact of Food Insecurity and Hunger on the Right to Health of Urban Poor Living in the State of Gujarat. In: Dev, S.M., Ganesh-Kumar, A., Pandey, V.L. (eds) Achieving Zero Hunger in India. India Studies in Business and Economics. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4413-2_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4413-2_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-4412-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-4413-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)