Abstract

We compare the development of Sustainable (Green) Supply in three regions of the world, the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in the Middle East, six countries in Europe, and six countries in Latin America, which were selected based on their Logistics Performance Index over a 10-year period. We based our empirical analysis on UN SDGs concerned with clean energy, innovation, sustainable communities, and climate action (SDGs 7, 9, 11, and 13, respectively). Using a modified RAM-DEA model, our results showed high logistics performance but significant divergence in green logistics performance among GCC countries. Countries in Western Europe led in terms of inputs that result in green outputs. Strong contenders in green supply chains include the UAE, Oman, México, Panamá, and Ecuador.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Global competitive pressures are forcing countries to strengthen their position in the world market through regional integration. With trade and customs agreements, individual countries have been enabled to improve their competitive position within a single regional market towards other regions and countries globally. This was also the incentive for the Gulf countries to establish a Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf in 1981, also known as Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), comprising Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Gulf integration has enabled facilitation of the movement of production, removing trade barriers, and coordinating economic policies, extending the size of the market to 35.65 million people who live in this region (Fernandes & Rodrigues, 2009). Moreover, it has created the preconditions for establishment of supply chains and sophisticated logistics networks with the aim of joint GCC exposure connecting the GCC as a region and globally. Internally, the GCC is an area of economic cooperation comprising the four freedoms akin to the EU. Externally, the GCC has a growing network of free trade agreements with various parts of the world, most notably with EFTA countries, the US (Framework Agreement for Trade, Economic, Investment and Technical Cooperation), Singapore (GCC-Singapore FTA), and Australia, and bilateral cooperation agreements of individual countries such as UAE with Mexico (World Bank, 2021; World Trade Organisation, 2021). According to the Statistical Centre for the Cooperation Council for the Arab Countries of the Gulf (GCC-Stat), total export of GCC countries was approximately USD 652 billion in 2018 with an increasing trend. The export of oil, natural gas, and chemical products are the most important exports; however, many other products form an important share of exports from GCC countries. For example, non-oil exports contribute 70% to the GDP of the UAE; however, these are mostly other commodities such as gold, jewellery, and electronics; a notable exception are the aerospace and defence sectors in which the UAE also excels and exports (OEC, 2021). No other country in the GCC has reached the same level of economic diversification as the UAE. On average, the oil and gas sector represents 70% of exports from the GCC (OEC, 2021).

Durugbo et al. (2020) found that supply chains in the GCC region confront three main challenges including “strategically selecting and integrating network resources”, “reliably contracting and delivering high-quality solutions”, and “cost effectively controlling and financing operational expansions” (Durugbo et al., 2020, p. 13).

One of the most rapid developing world regions by increasing worldwide circulation of commodities is the region of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries which have become a central node in global trade (Ziadah, 2018). The GCC region has a strategic geographic position between Asia and Europe and strong trade links with Africa. Durugbo et al. (2020) estimated that this region accounts for around 30% of the globally known oil reserves. According to Ziadah (2018), authorities in this region have recognised the possibility of economic diversification by making significant investments into logistics infrastructure: maritime ports, roads, rail, airports and logistics cities (El-Nakib, 2015; Stojanovic & Puska, 2021; Ziadah, 2018). According to Fernandes and Rodrigues (2009), GCC countries are positioning themselves to be logistic hubs by strengthening transport, and connectivity, and this can lead to attracting foreign investments. Durugbo et al. (2020) provided a useful insight into the existing literature of the supply chain management of the GCC region and found high levels of complexity and uncertainty within this regional business environment. One of the complexities found by these authors is related to strategically selecting and integrating network resources within the GCC region, focusing attention on the views of multinational companies towards regional supply chains. According to them, multinational companies located in the GCC region are very focused on regional supply chains. According to Memedovic et al. (2008), oil-producing countries, with exception of the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, perform below their potential and their logistics systems usually focus on their main export commodities rather than focusing on diversification on trade logistics. These authors pointed to an example of Dubai Ports World that has become one of the most important global port operators, operating 42 port terminals in 27 countries. In addition, the UAE has focused on its attention on cementing its maritime logistics efficiency by capitalising on its unique geographic advantage as the only country in the GCC with access to two bodies of water—the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman (Indian Ocean) rendering the country independent of the conflict-prone Straits of Hormuz. As a result, a number of efficient ports exist on both coasts, all of which are connected through superb road infrastructure inside the country. Memedovic et al. (2008) also pointed out that countries with better logistics capabilities can attract more foreign direct investments, decrease transaction costs, diversify export structure, and have higher growth. Accordingly, the UAE has posted the highest economic growth rates and has the highest LPI within the GCC and is in 11th place globally among its GCC peers (World Bank, 2021). In terms of supply chain competitiveness, the UAE is comparable to industrialised countries such as Switzerland, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Finland which are countries within two ranks (above and below) the UAE. As a result of the logistical strength of the UAE, the GCC therefore has a high overall mean LPI. The UAE is followed by Qatar, Oman, and Saudi Arabia in logistical strength at ranks, 30, 43, and 55, respectively, placing them into similar categories as industrialised emerging economies such as Poland and Slovenia in Europe, and Mexico, Chile, and Panama in Latin America (World Bank, 2021).

2 Relationship Between Trade Competitiveness and Supply Chain Efficiency: Examples

Supply Chain (SC) has become a key competitive advantage for companies globally (Bhatnagar & Teo, 2009; Hasani & Zegordi, 2015; Hülsmann et al., 2008; Johnson & Pyke, 2000; Kwak et al., 2018).

Effective management of Supply Chains can lead to a competitive advantage by supporting market strategy (Li et al., 2004). Since 2005, the company Procter & Gamble (P&G) considers three moments of truth as a part of its market strategy. The first moment of truth is when the consumer finds the right product on the shelf. P&G describes this as the “moment a consumer chooses a product over the other competitors’ offerings” (P&G, 2005). The second one is when the consumer uses the product to capture the perceived value (P&G, 2005). The third is when a customer shares feedback with the company as well as other prospective consumers (P&G, 2005). Moreover, in 2011, Google introduced the concept of Zero Moment of Truth (ZMOT). It happens when a customer searches websites and reviews about a product before purchasing it. In 2014, Eventricity Ltd. proposed the Less Than Zero Moment of Truth (<ZMOT), which is when a factor triggers a consumer to start looking for or searching a product. E-commerce provided a push factor towards optimisation of supply chains since profiting from all these moments of truth requires a fast, responsive, reliable, and resilient supply chains that is always ready to support any intended disruptive business model.

Many other studies have been conducted on the management of logistics operations that support the mentioned examples. One of these issues, as stated by Akkermans et al. (1999), is related to managing goods flows between facilities in a chain of operations, thus putting focus on the importance of coordinated planning approaches that can reduce costs. Several scholars have warned of the need to have an appropriate coordination in decision-making on the design of international facility networks. Coe et al. (2004) argued that with establishment of the global commodity chain approach, the importance of regions in economic activities arises. Önden et al. (2018) argued that the location of the logistics centres is a key element of the transport system and location decisions should be done strategically. Due to advantages for the economy, regional authorities want their region to be considered for logistical centres and this could lead to rising logistics costs, increasing travel distances by trucks, and lacking multi-modal transportation possibilities. This is particularly an issue for countries that follow a federal system of government (e.g. the UAE), where competing interests among regional rulers can lead to duplication of infrastructure and therefore non-optimisation of costs in the long term. However, negative effects are often cushioned when oil prices rise and are therefore not always given the sense of urgency it deserves. On the other hand, redundancies in infrastructure can also have positive effects, for example when back-up options are needed when a critical road undergoes maintenance. In some GCC countries, notably the UAE, examples of duplicate infrastructure can include too many roads connecting the same city pairs as well as transport hubs and companies in close proximity (e.g. Dubai and Abu Dhabi airports, Emirates Airline and Etihad Airways as global airlines) which are fully owned by the governments of their respective emirates (states), and ultimately the ruling families. Ownership is not shared, which means these are not federal assets and therefore sometimes may lack a coordinated approach when it comes to planning and shared resources, which could affect efficiency (Ziadah, 2018).

In his study of countries in the GCC, Ziadah (2018) also finds support for the argument of a large degree of duplication in port infrastructure in the region. Therefore, an analysis of GCC countries and their comparison to emerging and industrialising countries in Latin America for perspective is therefore justified and forms the focus of this study.

The chosen pair of regions which includes 6 countries in the GCC as a baseline (default), 6 countries selected based on high LPIs in Latin America, and 6 countries selected based on high LPI in Europe, is relevant because of the necessity to build long-term relationships and trade links between regions, which, according to Li et al. (2011), are critical factors in establishing successful logistics systems. Trade volume between the three regions has been rising as a result of multilateral trade and economic partnership agreements among the countries concerned (World Bank, 2018).

We selected the logistics indicator as a proxy by using the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) developed by the World Bank for the time periods 2000–2019.

The chapter is organised as follows. We discuss the conceptual and theoretical background, the research methodology, and results of our research followed by a discussion.

3 Green Supply Chains

Supply chain management is an area of increasing strategic importance due to global competition, outsourcing of noncore activities to developing countries, short product life cycles, and shortened lead times in all aspects of the supply chain (Skjøtt-Larsen et al., 2007). Management attention has moved from competition between firms to competition between supply chains and value chains (Ferrantino & Koten, 2019; Mangan & Christopher, 2005; Raei et al., 2019). The capability to establish close and long-term relationships with suppliers and other strategic partners has become a crucial factor in creating competitive advantage. At the same time, various stakeholders, including consumers, shareholders, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), public authorities, trade unions, and international organisations, are showing an increasing interest in environmental and social issues related to international business. Concepts such as supply chain sustainability (Abbasi & Nilsson, 2016; Koplin et al., 2007), triple bottom line (Elkington, 1997), environmental management (Handfield et al., 2005), corporate greening (Preuss, 2005), green supply (Bowen et al., 2001; Sarkis, 2003; Vachon & Klassen, 2006), and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in supply chains (Maloni & Brown, 2006; Pedersen & Andersen, 2006) have increasingly been studied and resulted in new findings by Kwak et al. (2018), Stekelorum et al. (2020), and Chan et al. (2020) across various industries, company types (MNCs and SMEs), and countries. An increasing number of companies, especially large multinational corporations, have implemented environmental annual reports, sustainability strategies, and voluntary codes of conduct. However, despite many multinational corporations’ efforts to implement social and environmental issues in their supply chains, a gap exists between the desirability of supply chain sustainability in theory and the implementation of sustainability in supply chains in practice (Bowen et al., 2001).

The green supply chain management model, which fully considers resource consumption and environmental impact of the supply chain has received wide attention in politics and business (e.g. Esen & El Barky, 2017; Meckling & Hughes, 2018; Zimon, 2017). The promotion of ecological aspects in many parts of consumer life and the continuous improvement of consumers’ environmental awareness, not only are green products becoming favoured by the market but also sustainable supply chains (Kuiti et al., 2019). Therefore, implementing green supply chain management practices and selling green products have become important measures for supply chain enterprises to occupy a favourable market position and obtain sustainable competitive advantages, so the topic is significant.

According to Christopher (2017, p. 304), “effective logistics and supply chain management can provide a major source of competitive advantage”. Having in mind the necessity of GCC countries to be included effectively into global supply chains while conforming to sustainability mandates set by the UN through its SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), we analysed logistical and green supply chain performance of GCC countries and a similar number of the most developed countries in Latin America.

The main research questions are:

-

1.

How sustainable are Logistics Networks in the three regions in terms of not only their LPI but also their contribution towards green supply chains (GLPI), mainly in fulfilment of SDGs 7, 9, 11, and 13?

-

2.

Which of these regions is likely to have an edge in terms of both Logistics Performance and Green Supply Chains combined in future?

-

3.

Are more logistical green initiatives being propagated as part of CSR and corporate image compared to their actual impact?

-

4.

What will be the implications of the findings for policymakers and businesses in the three regions?

4 Logistics Performance Index (LPI)

The Logistics Performance Index is a tool developed by the World Bank to identify the strengths and opportunities the countries have in their performance on trade logistics and what can be done to improve their performance. Logistics Performance Index attempts to provide a standardised method to compare supply chain efficiency among countries (World Bank, 2018).

The LPI is developed through a worldwide survey of operators on the ground (global freight forwarders and express carriers), providing feedback on how friendly is the logistics of the countries in which they operate and quantitative data on the performance of key components of the logistics chain in the subject country (World Bank, 2018).

According to the LPI 2018 edition, the UAE ranked first in the Arab world and 11th globally, followed by Oman, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Kuwait in the 2018 LPI report, while Egypt ranked seventh in the Arab standings, followed by Lebanon, Jordan, and Djibouti, with 67, 79, 84, and 90, respectively. Tunisia, the Comoros, Morocco, Algeria, Sudan, and Mauritania followed in the rank, while Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Iraq, and Libya were placed in last regionally (World Bank, 2018).

5 The Green Logistics Performance Index (GLPI)

Kim and Min (2011) introduced the GLPI by combining the LPI with the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) to develop a new performance measure that can assess the competitiveness of a country from the perspective of ecological sustainability and logistics productivity. Moreover, they declared the existence of interdependence between the LPI and the EPI. Similarly, Lu et al. (2019) adopted an approach of developing GLPI, but at company level. He measured the performance of a surveyed firm in various green logistics activities. The GLPI relies on the self-assessment of firms to report their performance in the surveyed green logistics activities.

Our method of DEA which closely follows Lu et al. (2019) focuses on the country level.

6 Green Supply Chains and LPI

Several authors have proposed Logistics Indexes related to Environmental impact. Some have correlated LPI and Environmental parameters such as CO2 emissions and oil consumption (e.g. Mariano et al., 2016). Mariano et al. (2016) proposed a CO2 emissions and logistics performance composite index “considering the importance of good logistics performance for low/no fossil-carbon economies especially because the transport sector is responsible for a substantial portion of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions”. They proposed a low carbon logistics performance index (LCLPI). This composite index and the ranking of countries in terms of logistics performance and CO2 emissions can help to identify the best performing countries in low carbon logistics.

Lu et al. (2019) proposed an improved composite index measured by logistics performance index (LPI), CO2 emissions, and oil consumption from the transport sector. The main finding of this research is that ELPI is strongly correlated with LPI, and countries with high performance in LPI generally perform well in ELPI.

7 Green Supply Chains and Sustainable Development Goals

Since SDGs are part of the global agenda, countries are expected to show progress in SDGs metrics (UN, 2021). It is important to confirm if that progress is really reflected in supply chain infrastructure and operation. Otherwise, SDG metrics improvement will be only a matter of public relations and image in face of the international community rather than pursuing a true positive impact on the environment.

During the last decade, some Arab countries such as the UAE have reported improvement in their SDG metrics associated with Sustainable Supply Chain factors (SDG Arab Report, 2019). Up to this point, we have not found formal evidence that this metric’s improvement is related to progress on sustainable (green) supply chain implementation in all subject countries of our research.

8 CSR and Green Supply Chains

It is now an established fact that radical innovations should be introduced for low carbon emissions; but most of the time, organisations are more interested in making marginal changes rather than going for emission prevention innovations (Berrone et al., 2013). Furthermore, cost minimisation being a significant economic objective for these organisations, they focus more on their budget constraints instead of focusing on low carbon emission front by making minor changes to their existing working styles, regimes, and functions (Jones & Levy, 2007; Neuhoff, 2005). Nations being aware of profiteering of the business sectors, have introduced corporate social responsibility (CSR) Act to align environmental protections clause with expanding future economic activities in order to reduce GHG emission along the value chain. Kleemann and Murphy-Bokern (2014) have shown that agriculture and agro-based firms have improved efficiency as a result of benefits of training, awareness, and networking of producers with improvements in the implementation of CSR.

In the UK, the Companies Act 2006 makes CSR an integral part of good governance especially for large companies; in the US, the corporate social responsibility (CSR) team in the Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs directs businesses in the promotion of responsible and ethical business practices. France, Denmark, South Africa, and China have a mandatory reporting on the amount spent on CSR activities. Alternately, it has also been observed that organisations are pushed to come out of their old established manufacturing mindsets by the competitive society and demanding customers to improve their environmental performance (Shultz & Holbrook, 1999). Besides these societal and customer pressures, there are also regulatory pressures (Qu et al., 2013; Okereke & Russel, 2010; Reid & Toffel, 2009). Consequently, management tends to channel the organisational sources and abilities towards complex climate change issues (Reid and Toffel, 2009; Howard-Grenville et al., 2014). However, the reality is sometimes far from theoretical assumptions; in fact, the important question here is: are organisations doing enough to face this problem?

In response to governmental policies and general awareness on environmental issues among all stakeholders, organisations have been incorporating environmental ecosystem for better carbon performance and sustainability (Seuring & Müller, 2008). Organisations need to move beyond economic objectives of minimising cost, saving water and energy (Pinto-Varela et al., 2011).

Multiple business operations like sourcing, manufacturing, and logistics have been found to be actively responsible for environmental problems (Beamon, 1999).

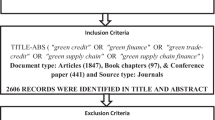

9 Research Design

Martí et al. (2017) highlighted that international trade has been affected by increased competitiveness of lagged regions that in the past did not play such an important role in the world. Thus, they believe that only those countries prepared to implement the advances that commercial globalisation requires can benefit from improved logistics performance. Measurement of performance must recognise the role of an organisation in a supply chain. Önden et al. (2018) pointed out that logistics performance is an accelerator of the competitiveness of a country and thus, they need to evaluate their position using various indicators including logistics performance index (LPI). Memedovic et al. (2008) indicated the usefulness of LPI as a composite index which shows that building the logistics capacity to connect firms, suppliers, and consumers is even more important today than costs. Thus, within logistics performance analysis for GCC countries, we will use LPI data. Biswas and Anand (2020) performed a comparative analysis of the G7 and BRICS countries on the basis of logistical competitiveness, and they expanded the criteria by using the adoption of information and communication technologies and CO2 intensity in addition to the LPI criteria.

Studies can be found in the literature that deal with the problem of selection of logistics centres using multi-criteria decision analysis, such as studies by Li et al. (2011). Li et al. (2011) analysed among 15 regional logistics centre cities and thirteen criteria to identify logistics centre location.

Pham et al. (2017) developed a benchmarking framework for selection of logistics centres and found that freight demand, closeness to market, production area, customers, and transportation costs are most important factors for selection. Biswas and Anand (2020) applied Proximity Indexed Values to perform a comparative analysis of the G7 and BRICS countries, while Wang et al. (2010) put their focus in selection of locations that maximise profits and minimise costs. Focusing on several criteria, such as proximities to highway, railway, airports, and seaports; volume of international trade; total population; and handling capabilities of the ports, Önden et al. (2018) combined spatial statistics and analysis approaches to evaluate suitable levels of performance for logistics centres.

We followed the method used by Martí et al. (2017) and Wang et al. (2018), who used improved composite indexes to compare the impact of green logistics on international trade in developed and developing countries using DEA.

10 Results

Using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), which is a data-driven and nonparametric mathematical programming approach, we obtained results for 18 countries in three regions using 6 parameters, divided into three parameters of slack inputs and 3 parameters of slack outputs. According to Cooper et al. (1999), the countries to be compared need to be three times the sum of slack inputs and outputs (18 countries) in order for the model to function. The slack inputs consist of three variables under SDGs 7 and 9, namely Clean Fuel (SDG 7), Articles (SDG 9), and Research and Development Expenditure (SDG 9). The slack outputs consist of three variables under SDGs 7, 9, and 13. These are Logistics Performance Index (LPI—SDG 9), CO2 emissions from fuel combustion/electricity output (CO2TWH—SDG 7), and energy-related CO2 emissions per capita (CO2PC—SDG 13), respectively.

The DEA method utilises multiple inputs and multiple outputs for evaluating the relative efficiency of homogeneous and comparable Decision-Making Units (DMUs). In contrast to radial models, the Slacks-Based Measures (SBM) identify all inefficiencies of the concerned DMU by taking input excesses and output shortfalls into the evaluation. The SBM model identifies all inefficiencies of the concerned DMU by taking input excesses and output shortfalls into the evaluation. All DMUs can be partitioned into two mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive sets efficient and inefficient by the SBM model, nevertheless, the model fails to discriminate between efficient DMUs (Table 28.1).

According to the table above, the results show that those countries showing 0 in the tables run at optimal efficiency in terms of inputs versus output ratios. However, it should be noted that all results are relative, both across countries, and across inputs versus outputs, which does not automatically mean that “efficient” is “good”. Efficiency can also be a result of low inputs and low outputs, which is not necessarily good. The interpretation for efficient countries simply means that their outputs are efficient relative to inputs if the result shows 0. What we can see from the results is that.

(1) The countries of the Middle East, in general, are very similar. Their efficiencies are adequate for the inputs and outputs they have. However, the results do not indicate absolute values of inputs and outputs.

(2) For European countries, the results are more mixed. Some inefficiencies can be seen for Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Austria. However, these countries overinvest in Rdex (SDG 9) in the case of Austria, and in Articles (SDG 9) for the case of the UK and Switzerland. Despite having efficiencies of 1, the case of Switzerland is special, since it has excesses in publications and R&D investments, being able to further reduce its CO2 emissions.

Hence, for the amounts of investment, the outputs are not yet satisfactory. Output inefficiencies can be seen in CO2TWH (CO2 emissions from fuel combustion—SDG 7) and CO2PC (Energy-related CO2 emissions per capita—SDG 13). This is not necessarily a negative aspect; it simply means that the mentioned countries invest a great deal, but have not yet obtained matching returns on their investment.

In the case of countries in the Middle East, they may not be investing enough relative to their GDPs and the outputs are correspondingly matching the inputs, still showing up as efficient. As a matter of fact, several large projects aimed at building renewable energy capacities and sustainable cities in the Middle East have failed or been abandoned since inception. A prominent example is Masdar City near Abu Dhabi, which was meant to be a large-scale green city powered by solar electricity with one of largest fields of solar panels in the Middle East, but it has been abandoned since 2015. However, the UAE has plans to increase investment in sustainable energy production by 500% in the coming decade (2020–2030) (Reuters, 2020), but the outcome is yet to be seen. According to IRENA (2021), GCC countries intend to reach 72 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030 through solar power. However, the output across the GCC in solar energy in 2019 was only about 800 MW, led by the UAE and Oman (IRENA, 2021). As the largest economy, the share of Saudi Arabia’s output in renewable energy was significantly smaller than the former two neighbour countries (Statista, 2021) indicating that there is still a long way to go in investment in green energy.

In Latin America, it should be noted that Chile, Brazil, and Argentina have some inefficiencies. Brazil and Argentina have efficiencies below 90. Brazil has an excess in in research and development (9_redex—R&D Expenditure) relative to its CO2 emissions outputs. In the case of Chile, it has an excess of publications and could improve its CO2 emissions indicators. As for Argentina, it could improve its performance in the Logistics Performance Index (LPI).

11 Extended Model RAM-DEA

In addition to the model above, we conducted a more specific analysis using the Range Adjusted Measure DEA model (RAM-DEA), which is a non-radial and non-angular model. In addition to the previous model, this model avoids subjectively setting model parameters (Lu et al., 2019). The model supports good and bad outputs. The selection of the inputs and outputs aims to create an index which considers green logistics SDGs indicators, specifically SDGs 7, 9, 11, and 13.

Since the model aims to minimise inputs, we selected oil consumption as the only input. In a similar way, the model maximises the good outputs and minimises the bad outputs. Following the same logic, the only good output chosen was the LPI. The rest of the outputs are related to CO2, and therefore it is desirable to minimise them (bad outputs). To run the programme and adapt the free library for R programming, the bad outputs were introduced as inputs (Table 28.2).

According to the model results, there are four countries which could be considered efficient: Panama and Brazil in Latin America, and Germany and Sweden in Europe.

GCC countries obtained an inefficient index compared to countries in Europe and Latin America. The most inefficient components for these countries are the oil consumption and the annual mean concentration of particulate matter of less than 2.5 microns of diameter. The most inefficient countries were Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

12 Conclusions

It can be seen that countries are generally moving in the direction of sustainable logistics. The data for European countries shows that significant investments (inputs) are being made while results relative to the investments are not yet always obtained. However, countries such as the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Austria have other constraints of not being fully integrated with the EU, either due to being non-EU members (Switzerland and UK), being landlocked (Switzerland and Austria), or being geographically insular in addition to outside the EU (the UK). Therefore, inefficiencies in the LPI could have result from these factors. The other results are as expected, in that countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, are fully efficient in terms of green LPI.

The scenario was more mixed for countries in the Middle East. The initial model listed all as being efficient; however, the inputs have not been consistently high or of significant duration, such as the green project of Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, the very low share of solar energy generation in the largest GCC economy Saudi Arabia, and generally low inputs from countries such as Kuwait and Qatar. By this account, it can still be seen that the UAE and Oman are ahead of the remaining four economies of the GCC in terms of sustainable logistics.

For countries in Latin America, the results were more mixed, especially in the second model. A common problem is CO2 emissions, especially those experienced by the larger economies of Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. Although the model shows that investments in research and development are being made (Rdex—SDG 9), especially in Brazil, the effects of these investments have not yet materialised in the case of Brazil. We can also see that Chile is making headways in academic research of sustainability as evidenced by SDG 9 – Articles in Table 28.1, but, similarly, the effects are not yet matched by outputs. A similar scenario of academic research applies to Argentina, albeit on a smaller scale, where inputs are not matched by outputs.

With respect to the results of this study, further areas of research could therefore focus on examining methods to increase “good” inputs in the GCC effectively, such as research regarding green technologies as well as research and development expenditure relative to GDP, in accordance with SDG 9, as European countries and several emerging countries in Latin America seemed to have an edge with regard to “good” inputs. For countries in the GCC, such research could focus on how technologies outside the oil and gas sector with already high existing local potential and several globally competitive local companies (e.g. in the metallurgy, aerospace, chemical sectors in the UAE) could be leveraged (Elrahman et al., 2020).

13 Implications for Countries in the GCC

A strong argument in the pursuit of the development of green energies and supply chains in the GCC has come from the opportunities for technological progress and job creation that renewable energies offer (Al-Ubaydli, 2021). In many traditional sectors, productivity growth has stagnated during the last 20 years, but the renewable energy sector continues to allow for large improvements in productivity, and this is reflected in the sharp declines in generation cost witnessed by solar energy during the last decade. This view is supported by Qudah et al. (2016), who found that high reliance on oil and gas has resulted in the reduction of productivity in other sectors resulting in lower aggregate economic output, hence lower country competitiveness. This is a strong incentive to turn towards a green economy by investing in renewable energies that could boost economic growth through its impact on productive efficiency. With the shift in investments come positive effects for programmes of localisation of the workforce, which all GCC countries have been pursuing through programmes known as Emiratisation, Saudisation, Qatarisation, Omanisation, Kuwaitisation, and Bahrainisation. As technological advances in IT and artificial intelligence have increasingly begun to replace even white-collar jobs, presenting a threat of structural unemployment among GCC citizens, renewable sources of energy could create a considerable number of attractive and sustainable jobs, which would ultimately benefit the citizens of GCC countries.

In addition to economic benefits at national levels, there are strong indicators that countries in the GCC have also recognised the value of pursuing green economies as a matter of international reputation and geopolitical influence in the region. At the recently concluded COP26, the UAE has announced a net-zero energy goal by 2050, while Bahrain has announced the same goal to be achieved by 2060 (Osman, 2021). In addition, the UAE will be the host of COP28 in 2023, further highlighting its commitment to green goals while taking advantage of the opportunity to assume a regional leadership role, which might incentivise neighbour countries to step up, and ultimately have positive aggregate effects for environmental sustainability at a global level.

References

Abbasi, M., & Nilsson, F. (2016). Developing environmentally sustainable logistics: Exploring themes and challenges from a logistics service providers’ perspective. Transportation Research Part d: Transport and Environment, 46, 273–283.

Akbari, M., McClelland, R. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and corporate citizenship in sustainable supply chain: a structured literature review. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(6), 1799–1841.

Al-Ubaydli, O. 2021. Why Are the GCC Countries Trying to Go Green? Expert Opinion. Valdai Club. https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/why-are-the-gcc-countries-trying-to-go-green/?sphrase_id=1370929 accessed 30 December 2021.

Beamon, B. M. (1999). Designing the green supply chain. Logistics Information Management, 12(4), 332–342.

Berrone, P., Fosfuri, A., Gelabert, L., & Gomez‐Mejia, L. R. (2013). Necessity as the mother of ‘green’inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strategic Management Journal, 34(8), 891–909.

Bhatnagar, R., & Teo, C. (2009). Role of logistics in enhancing competitive advantage a value chain framework for global supply chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 39(3), 202–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030910951700

Biswas, S., & Anand, O. P. (2020). Logistics competitiveness index-based comparison of Brics and G7 countries: An integrated PSI-PIV approach. IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, 17(2), 32–57.

Bowen, F. E., Cousins, P. D., Lamming, R. C., & Farukt, A. C. (2001). The role of supply management capabilities in green supply. Production and Operations Management, 10(2), 174–189.

Chan, C. K., Man, N., Fang, F., & Campbell, J. F. (2020). Supply chain coordination with reverse logistics: A vendor/recycler-buyer synchronized cycles model. Omega, 95, 102090.

Chen, Z., Kourtzidis, S., Tzeremes, P., & Tzeremes, N. (2020). A robust network DEA model for sustainability assessment: An application to Chinese provinces. Operational Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-020-00553-x

Christopher, M. (2017). Relationships and alliances embracing the era of network competition. In Strategic supply chain alignment. 286–351. Routledge.

Cooper, W. C., Park, K. S., & Pastor, J. T. (1999). A range adjusted measure of inefficiency for use with additive models, and relations to other models and measures in DEA. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 11, 5–42.

Durugbo, C. M., Amoudi, O., Al-Balushi, Z., Anouze, A. L. (2020). Wisdom from Arabian networks: a review and theory of regional supply chain management. Production Planning & Control, 1–17.

El-Nakib, I. (2015). The business value of supply chain security: Empirical study on the Egyptian drinking milk sector. International Journal of Value Chain Management, 7(3), 216–240.

Elkington, J. (1997). The triple bottom line. Environmental management: Readings and cases, 2.

Elrahmani, A., Hannun, J., Eljack, F., & Kzi, M. K. (2020). Status of renewable energy in the GCC region and future opportunities. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering, 31, 1–12.

Environmental Performance Index (2020). Environmental performance index 2020, second quarter 2020. https://epi.yale.edu/ . Accessed 22 May 2021.

Esen, S. K., El Barky, S. S. (2017). Drivers and barriers to green supply chain management practices: The views of Turkish and Egyptian companies operating in Egypt. In ethics and sustainability in global supply chain management (pp. 232–260). IGI Global.

Fernandes, C., Rodrigues, G. (2009). Dubai’s potential as an integrated logistics hub. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 25(3).

Ferrantino, M. J., Koten, E. E. (2019). Understanding Supply Chain 4.0 and its potential impact on global value chains. Global value chain development report 2019. 103.

Handfield, R., Sroufe, R., & Walton, S. (2005). Integrating environmental management and supply chain strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 14(1), 1–19.

Hasani, A., & Zegordi, S. H. (2015). A robust competitive global supply chain network design under disruption: The case of medical device industry. International Journal of Industrial Engineering & Production Research, 26(1), 63–84.

Howard-Grenville, J., Buckle, S. J., Hoskins, B. J., & George, G. (2014). Climate change and management. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 615–623.

Hülsmann, M., Grapp, J., & Li, Y. (2008). Strategic adaptivity in global supply chains-competitive advantage by autonomous cooperation. International Journal of Economics, 114(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2007.09.009

Johnson, M., & Pyke, D. (2000). A framework for teaching supply chain management. Production and Operations Management, 9(1), 1–18.

Jones, C. A., & Levy, D. L. (2007). North American business strategies towards climate change. European Management Journal, 25(6), 428–440.

Karaman, A. S., Kilic, M., & Uyar, A. (2020). Green logistics performance and sustainability reporting practices of the logistics sector: The moderating effect of corporate governance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120718.

Kim, I., & Min, H. (2011). Measuring supply chain efficiency from a green perspective. Management Research Review, 34(11), 1169–1189.

Kleemann, L., & Murphy-Bokern, D. (2014). Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food sector: Effects of corporate responsibility. (No. 1967). Kiel Working Paper.

Koplin, J., Seuring, S., & Mesterharm, M. (2007). Incorporating sustainability into supply management in the automotive industry–the case of the Volkswagen AG. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15(11–12), 1053–1062.

Kuiti, M. R., Ghosh, D., Gouda, S., Swami, S., & Shankar, R. (2019). Integrated product design, shelf-space allocation and transportation decisions in green supply chains. International Journal of Production Research, 57(19), 6181–6201.

Kwak, D., Seo, Y., & Mason, R. (2018). Investigating the relationship between supply chain innovation, risk management capabilities and competitive advantage in global supply chains. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(1), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-06-2015-0390

Li, Y., Liu, X., & Chen, Y. (2011). Selection of logistics centre location using Axiomatic Fuzzy Set and TOPSIS methodology in logistics management. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(6), 7901–7908.

Li, S., Ragu-Nathanb, B., Ragu-Nathanb, T., Raob, S. (2004). The impact of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and organizational performance. Omega: International Journal of Management Science, 34, 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2004.08.002

Lu, M., Xie, R., Chen, P., Zou, Y., & Tang, J. (2019). Green transportation and logistics performance: An improved composite index. Sustainability, 11, 1–18.

Mangan, J., Christopher, M. (2005). Management development and the supply chain manager of the future. The International Journal of Logistics Management.

Maloni, M. J., & Brown, M. E. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in the supply chain: An application in the food industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(1), 35–52.

Mariano, E. B., Gobbo, J. A., Castro Camioto, F., & Nascimento Rebelatto, D. A. (2016). CO2 emissions and logistics performance: A composite index proposal. Journal of Cleaner Production, 163(2017), 166–178.

Martí, L., Martín, J. C., & Puertas, R. (2017). A DEA-logistics performance index. Journal of Applied Economics, 20(1), 169–192.

Meckling, J., & Hughes, L. (2018). Protecting solar: Global supply chains and business power. New Political Economy, 23(1), 88–104.

Memedovic, O., Ojala, L., Rodrigue, J. P., & Naula, T. (2008). Fuelling the global value chains: What role for logistics capabilities? International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development, 1(3), 353–374.

Neuhoff, K. (2005). Large-scale deployment of renewables for electricity generation. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(1), 88–110.

Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) (2021). Country Profiles: United Arab Emirates. https://oec.world/en/profile/country/are. Accessed 14 July 2021.

Okereke, C., & Russel, D. (2010). Regulatory pressure and competitive dynamics: Carbon management strategies of UK energy-intensive companies. California Management Review, 52(4), 100–124.

Önden, İ, Acar, A. Z., & Eldemir, F. (2018). Evaluation of the logistics center locations using a multi-criteria spatial approach. Transport, 33(2), 322–334.

Pedersen, E. R., & Andersen, M. (2006). Safeguarding corporate social responsibility (CSR) in global supply chains: How codes of conduct are managed in buyer-supplier relationships. Journal of Public Affairs: An International Journal, 6(3–4), 228–240.

Pham, T. Y., Ma, H. M., & Yeo, G. T. (2017). Application of fuzzy delphi topsis to locate logistics centers in vietnam: The Logisticians’ perspective. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 33(4), 211–219.

Pinto-Varela, T., Barbosa-Póvoa, A. P. F., & Novais, A. Q. (2011). Bi-objective optimization approach to the design and planning of supply chains: Economic versus environmental performances. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 35(8), 1454–1468.

Preuss, L. (2005). Rhetoric and reality of corporate greening: A view from the supply chain management function. Business Strategy and the Environment, 14(2), 123–139.

Qu, X., Alvarez, P. J., & Li, Q. (2013). Applications of nanotechnology in water and wastewater treatment. Water Research, 47(12), 3931–3946.

Qudah, A. A., Badawi, A., & AboElsoud, M. E. (2016). The impact of oil sector on the global competitiveness of GCC countries: Panel data approach. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 7(20), 32–39.

Raei, M. F., Ignatenko, A., Mircheva, M. (2019). Global value chains: What are the benefits and why do countries participate? International Monetary Fund. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/148274/1/The%20Impact%20of%20Oil%20Sector%20on%20the%20Global%20Competitiveness%20of%20GCC%20Countries_Panel%20.pdf accessed 30 December 2021.

Rakhmangulov, A., Sladkowski, A., Osintsev, N., Muravev, D. (2017). Green logistics: Element of the sustainable development concept. Part 1. NAŠE MORE: znanstveni časopis za more i pomorstvo, 64(3), 120–126.

Reid, E. M., & Toffel, M. W. (2009). Responding to public and private politics: Corporate disclosure of climate change strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 30(11), 1157–1178.

Sachs, J., Schmidt-Traub, G., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., & Fuller, G. (2019). Sustainable Development Report 2019. Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Sarkis, J. (2003). A strategic decision framework for green supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 11(4), 397–409.

Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1699–1710.

Shultz, C. J., & Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Marketing and the tragedy of the commons: A synthesis, commentary, and analysis for action. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 18(2), 218–229.

Skjott-Larsen T, Schary PB, Kotzab H, Mikkola JH (2007) Managing the global supply chain. Copenhagen Business School Press DK.

Statista—The Statistics Portal for Market Data, Market Research and Market Studies. 2021. www.statista.com. Accessed 14 July 2021.

Stekelorum, R., Laguir, I., & ElBaz, J. (2020). Can you hear the Eco? From SME environmental responsibility to social requirements in the supply chain. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 158, 120169.

Stojanović, I., & Puška, A. (2021). Logistics Performances of Gulf Cooperation Council’s Countries in Global Supply Chains. Decision Making: Applications in Management and Engineering, 4(1), 174–193.

Sustainable Development Report (2019a). SDG Index and Dashboard Report 2019a Arab Region, fourth quarter 2019. https://www.sdgindex.org/. Accessed 11 February 2021.

Sustainable Development Report (2019b). Part 3 Country Profiles, fourth quarter 2019b. https://www.sdgindex.org/. Accessed 11 February 2021.

Sustainable Development Report (2019c). Sustainable Development Report 2019c Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, second quarter 2019, https://www.sustainabledevelopment.report/. Accessed 26 February 2021.

United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. (2018). Basis for a long-term sustainable development vision in Mexico, progress on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Accessed 11 February 2021.

Vachon, S., Klassen, R. D. (2006). Extending green practices across the supply chain: The impact of upstream and downstream integration. International Journal of Operations & Production Management.

Wang, H., Ko, J., Zhu, X., Hu, S. J. (2010). A complexity model for assembly supply chains and its application to configuration design. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, 132(2).

Wang, Y., Hazen, B. T., Mollenkopf, D. A. (2018). Consumer value considerations and adoption of remanufactured products in closed-loop supply chains. Industrial Management & Data Systems.

World Bank (2021). Global preferential trade agreements database. https://wits.worldbank.org/gptad/database_landing.aspx. Accessed 14 July 2021.

World Bank (2018). LPI global rankings, 2018. https://lpi.worldbank.org/international/global?sort=asc&order=Country#datatable . Accessed 14 July 2021.

World Trade Organization (2021). Regional trade agreements. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/region_areagroup_e.htm. Accessed 14 July 2021.

Tone, K., Toloo, M., & Izadikhah, M. (2020). A modified slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 287(2), 560–571.

United Nations. (2021). The Sustainable Development Goals Report. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/. Accessed 15 February 2023.

Zegordi, S., & Hasani, A. (2015). A robust competitive global supply chain network design under distruption: The case of medical device industry. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Production Research, 26(1), 63–84.

Ziadah, R. (2018). Constructing a logistics space: Perspectives from the Gulf cooperation council. Environment and Planning d: Society and Space, 36(4), 666–682.

Zimon, D. (2017). The impact of implementation of the requirements of the ISO 14001 standard for creating sustainable supply chains. Calitatea, 18(158), 99.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wollenberg, A., Lazarini, J.G.O.C., Lazarini, J.J.C., Parra, L.F.O., Kakade, A.S. (2023). Green Supply Chains: A Comparative Efficiency Analysis in the Gulf and Beyond. In: Rahman, M.M., Al-Azm, A. (eds) Social Change in the Gulf Region. Gulf Studies, vol 8. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7796-1_28

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7796-1_28

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-7795-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-7796-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)