Abstract

This chapter shows that individuals’ trajectories in personal networks and the labour market are closely intertwined. A person’s network facilitates access to jobs in different ways. As people create relationships and accumulate social contacts, they obtain more information about job opportunities and embark on more rewarding careers. However, personal relationships may also hamper employment prospects. If employers expect that the obligations accruing from family-care reduce productivity, the consequence will be stunted careers and lower wages, notably for mothers. Yet the extent to which social relations help or hinder work trajectories varies across Europe and crucially depends on employment and family policies. Moreover, the spill-over effects between the two life domains travel both ways as employment outcomes also affect personal relationships. A prime example is how job loss affects the stability of partnerships. While recessions reduce the divorce rate at the aggregate level, the minority of individuals who lose their jobs are more likely to see their couples break up. Our chapter discusses the theory of spill-over effects between social relations and employment and reviews cutting-edge research in economics and sociology on the topic.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Social networks

- Unemployment

- Jobs

- Wages

- Labour markets

- Weak and strong ties

- Maternity leave

- Motherhood wage penalty

Introduction

Few human institutions lend themselves to the study of the interdependencies between the social sphere and the economic sphere as well as the labour market. The issue of how one social domain spills over into another is particularly relevant for the link between personal relationships and employment outcomes. In this chapter, the focus is on two instances of interdependencies between sociability and employment.

On the one hand, we will show that individuals’ trajectories in personal networks and the labour market are closely intertwined. A person’s network facilitates access to jobs in different ways. As people create relationships and accumulate social contacts, they obtain more information about job opportunities, benefit from acquaintances who vouch for them and thus may embark on more rewarding careers (Granovetter, 1974). However, social contacts must be nourished, or they can become obsolete (Calvo-Armengol & Jackson, 2004). In this view, personal connections can be seen as a form of relational reserve for achieving a successful labour market career over the life course (Cullati et al., 2018). While the lack of social contacts negatively affects employability, the extent to which personal networks influence individuals’ job trajectories depends on both the nature of connections and the characteristics of the labour market.

On the other hand, personal relationships may also hamper employment prospects. If employers expect the obligations accruing from individuals’ social lives to impair their commitment to the firm and reduce their productivity at work, employers will not hire these individuals or may discount their wages. This is notably the case for obligations linked to family and childcare. Crucially, the extent to which these social relations hamper careers depends on gender. While a large literature in sociology and economics points to a motherhood wage penalty for women (Gangl & Ziefle, 2009; Kleven, Landais, Posch, et al., 2019), there is little evidence on a fatherhood wage penalty—if anything, men’s earnings tend to increase when they have children (Glauber, 2018).

This chapter aims to shed light on the interdependencies between sociability and employment by discussing two spill-over effects: the effect of personal contacts on employment and the effects of family obligations and, notably, children on wages. For each of these two interdependencies, we first discuss the theory and then present recent empirical findings both from a broader international literature and from our own research over the last decade within the LIVES programme.

How Social Contacts Affect Employment Outcomes

The connection between one’s social sphere and the labour market has long been acknowledged in many disciplines. With some approximation, one may date the first set of solid empirical evidence and theoretical frames to the work of Mark Granovetter (1973, 1974), a sociologist who investigated the incidence of jobs found through personal contacts in the United States. Much of Granovetter’s work was organised around the idea that weak ties, that is, personal contacts and acquaintances outside the restricted circle of family and close friends (the strong ties), were crucial for obtaining information about vacant jobs. The key insight of this argument is simple: Weak ties generate much more extensive networks than the limited set of strong ties, thereby allowing people to be connected more extensively and to access a broader set of potential sources of information about job opportunities.

Despite the appeal of Granovetter’s argument, empirical evidence suggests that both strong and weak ties are important. Individuals with large, extended networks of weak ties do appear to be more frequently employed. At the same time, there is a substantial degree of continuity between parents and children in terms of the occupation—and even the detailed job—chosen. Two recent studies in Sweden show that children are likely to end up working with the exact same employers as their parents (Corak & Piraino, 2011; Kramarz & Skans, 2014). Moreover, we also know that closed elite circles of friends, often those coming from the same elite schools, are crucial for success in the labour market (Forsé, 2001; Lerner & Malmendier, 2013).

A large body of theoretical work rationalises the role of these two types of social connections, i.e., strong and weak ties. Many of these contributions are rooted in the branch of the economic discipline commonly referred to as the economics of information (Akerlof, 1970; Spence, 1973; Stiglitz & Shapiro, 1984). The discussion can be usefully organised around two broad types of information problems. First, neither employers looking for job candidates nor workers looking for jobs know exactly where to find each other. When jobseekers start looking for a new job, they often need to spend time and effort determining which employers are hiring for what kind of jobs. Public employment services, job advertisements and, more recently, job-finding websites and applications can all be viewed as tools that have been developed to alleviate this information deficit.

The second information problem is related to the characteristics of the job and the worker. Once the jobseeker and the employer with a vacant job have found each other, they need to invest yet more time and effort to figure out whether they can be good partners (Akerlof, 1970). Employers spend a substantial budget to screen and interview jobseekers in attempts to acquire information about whether these candidates would be able to carry out the required job tasks and whether, more broadly, they would fit well in their organisation’s work environment. Similarly, jobseekers also need to determine whether the advertised job is appropriate for their tastes and abilities and whether the employer is solid and will pay wages regularly.

Strong and weak ties may alleviate both types of informational problems, but they do so differently. Weak ties are more powerful at facilitating access to information about jobs and candidates. Several theoretical models (among others by Calvo-Armengol & Jackson, 2004; Zenou, 2015) postulate a mechanism in which information about job vacancies flows at a given rate to individuals, who can then decide to use this information for themselves or pass it on to their social contacts. Employed individuals are more likely to pass on the information than unemployed individuals, unless the former want to change their current job. Hence, people with more extended networks, even if such networks consist mostly of weak ties, are more likely to find new jobs, especially when they become unemployed and especially if many of their contacts are employed.

Regarding the second information problem, Montgomery (1991) proposes a theory of social contacts and workers’ screening that rests on the idea of social homophily: the notion that social ties, especially strong ties, are more likely to be established between individuals with similar characteristics. Employers internalise this information when they assess the profiles of job candidates who have been referred to them by someone they already know, typically one of their current employees. In such situations, the employer makes inferences on job candidates’ difficult-to-observe characteristics by considering the same characteristics of the referee, whom they already know.

The empirical predictions of this theory are supported by evidence. For example, employers, especially those employing highly skilled workers who are difficult to find and screen, value the information offered by recommenders so highly that they often require such recommendations as part of the application package.Footnote 1 Moreover, in tight labour markets, it is not unusual for employers to offer monetary rewards for their employees who recommend new hires.Footnote 2 The theory also predicts that jobseekers who access jobs via strong ties should find substantially better jobs compared to those found via weak ties, even holding the overall size of the extended network fixed.

Of course, the two mechanisms described here do not exhaust the wealth of theoretical work in this area, but they are representative of the fruitful cross-pollination taking place at the intersection of sociology and economics (see Granovetter, 2005 for a review). For example, the role of social networks in schools has been the subject of research both in economics (De Giorgi et al., 2010; De Giorgi & Pellizzari, 2014) and sociology (Frank et al., 2013; Gamoran et al., 2016) in a process of mutual cross-discipline learning.

An interesting further development concerns the potential trade-off between the two mechanisms. Notably, young jobseekers may have networks connecting them to occupations that are not necessarily those they prefer or are most skilled for. In such situations, they may face the difficult decision between continuing their job search or accepting a job they do not

enjoy much or in which their skills are not the most valued, possibly following in their parents’ footsteps (Bentolila et al., 2010).

Social Contacts and Employment Outcomes in Europe

Evidence on the importance of social contacts in the labour market is abundant, especially for European countries. Recent evidence comes from the 2016 European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) produced by Eurostat, which asked all young, employed workers how they had found their jobs (as part of an ad hoc module on youth employment, this question was addressed only to respondents aged 15 to 34).

Figure 4.1 shows that personal contacts such as relatives, friends or acquaintances are among the most commonly used and successful methods. On average, in the European Union, over one-third of employed young workers declare that they found their job through personal contacts. This proportion ranges from 55 percent in Latvia to 23 percent in Norway. Only direct applications, such as sending an application directly to an employer or being contacted directly by an employer, rival personal contacts in importance. Comparative information for the entire population in Europe is only available up to the early 2000s but strongly suggests that the relevance of social contacts in the labour market is as great for the entire active labour force as it is for young workers (Pellizzari, 2010).

Of course, it is difficult to know exactly how personal contacts helped in finding the job, whether the person simply informed the young worker about the existence of a vacancy or if there was a more direct and influential intervention with a given employer. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that social contacts matter so much even in labour markets with effective formal channels—public employment services and job-finding websites—to help people find jobs.

The Role of Social Contacts for the Unemployed

Of particular policy interest is the question of how social contacts help unemployed jobseekers return to a job, as the results from studies on employed workers may not easily generalise to unemployed jobseekers (Bonoli, 2014). The reason is that these studies include many nonsearchers: employed individuals who changed jobs only because they had received unsolicited information from personal contacts.Footnote 3 Accordingly, these studies may lead us to overestimate the importance of social ties for unemployed jobseekers.

Useful evidence stems from a large sample of unemployed jobseekers in Switzerland who were surveyed twice, at entry into and exit from the public unemployment system, and whose survey responses were matched with information from the unemployment insurance register (von Ow, 2016). These data show that over 40 percent of unemployed workers found a job through their social networks (Oesch & von Ow, 2017).

Interestingly, among unemployed individuals, those individuals with less social capital tend to rely more heavily on their social network to find a job than more advantaged social categories. Almost half of unemployed jobseekers in working-class occupations had found a job thanks to a personal contact, compared to only one-third of jobseekers in upper-middle class occupations. Therefore, it may not be merely the quantity and quality of social ties that determine whether a jobseeker uses personal contacts to secure employment. Rather, personal contacts and, notably, family, friends and acquaintances may be used by jobseekers who have fewer formal credentials to offer (Chua, 2011; Bonoli & Turtschi, 2015; Oesch & von Ow, 2017).

This analysis of unemployed jobseekers suggests that the decisive distinction may not necessarily be between weak and strong ties but rather between work-related and communal ties. Communal ties such as family, friends, neighbours and acquaintances primarily help more vulnerable jobseekers find a job, such as individuals without upper-secondary education, the low-skilled working class and jobseekers dismissed for noneconomic reasons. For these groups, family, friends and acquaintances step in and compensate for the difficulty of finding a job through other channels. Jobs found through communal contacts are then associated with lower wages and longer unemployment duration than jobs obtained via work-related contacts. In contrast, jobseekers with higher education disproportionately find their jobs through work-related contacts such as former colleagues and other work acquaintances (Oesch & von Ow, 2017).

Given the importance of social contacts in the labour market, it seems plausible that providing unemployed workers with extra information on how to use them effectively in job searches may shorten unemployment duration (Bonoli, 2014). A randomised intervention in Switzerland that provided such additional in-person advice to one half of jobseekers newly entering unemployment, but not to the other half, did not produce any overall effect. The intervention improved job finding only for women but not for men (Arni et al., 2020).

Two hypotheses possibly explain this gender difference. The labour market value of social contacts may be more regularly tapped by men than women, and men therefore do not need to be further nudged to use it—or, alternatively, social contacts are simply a more effective job search channel for unemployed women than unemployed men.

How Parenthood Status Affects Employment Outcomes

Another example of how one life domain spills over into another—how social relations affect labour market outcomes—is a worker’s family status. A large literature in sociology and economics points to a motherhood wage penalty for women that is often mirrored by a fatherhood wage premium for men. Again, a simple model helps to clarify the interdependency between sociability and employment.

Employers recruit from either a pool of applicants if they publicly announced the job or a set of personal suggestions provided by their social contacts. Employers look for new hires whose productivity—their output during working hours—exceeds the labour costs. While productivity is a central concept and sharply defined in theory, it is vague empirically. Productivity refers to the contribution made by workers to the firm’s production of goods and services during their working hours. Employers, when assessing productivity, will focus on an applicant’s commitment to the firm, her or his motivation to perform well, and his or her likely career prospects in the firm.

When a single individual without children applies to a position, productivity, commitment and motivation may be inferred from standard indicators such as education, experience, and recommendations from previous employers. Motivation and commitment are likely to be high if the match between the employer and the new hire is good. However, all this may change when an applicant indicates that he or she has children. In the employer’s eyes, children are a demand on a worker’s time and energy that may potentially compete with the time and energy devoted to work. Such competition is particularly likely if the new hire is the primary carer for the child because, in this case, his or her commitment may be first and foremost to the child and not the new employer. Employers may therefore discount the value of a new hire with a child compared to a new hire without children at equal levels of education, experience, and recommendation quality because, looking ahead, they expect that the new hire will contribute less to the firm.Footnote 4

Naturally, there are also differences on the side of the applicants. People who are looking for a job with a child may also be less likely to apply to the most demanding positions, anticipating the difficulty of reconciling work and family life. Instead, they may exchange lower wages for a family-friendly job that is compatible with childcare.

Whether mothers or fathers are affected by children depends on who becomes the primary carer for children. To the extent that women are still the primary carers in most couples across Europe, employers may discount applications from mothers even in couples with an egalitarian division of labour. Therefore, the birth of a child may drive a wedge between the careers of mothers and fathers of young children.

Motherhood and Wages

Empirical evidence consistently shows that women with children tend to earn lower wages than women without children across Europe and Northern America (Kleven, Landais, Posch, et al., 2019). This result is even found in Denmark, one of the world’s most gender-egalitarian countries (Kleven et al., 2019). Longitudinal data from panel surveys and administrative registers makes it possible to measure the motherhood wage gap by accounting for individuals’ predispositions and abilities that are constant over time (using the fixed-effects estimator). For Europe, longitudinal analyses using this design show a motherhood wage gap that is particularly large in Austria and Germany, intermediate in the UK and comparatively small in the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Finland, and Sweden (Gangl & Ziefle, 2009; Kleven, Landais, Posch, et al., 2019). While differences in work experience and job characteristics account for part of this disparity, basically all these studies report an unexplained wage gap between mothers and non-mothers, which raises the question of discrimination and forces researchers to look beyond market mechanisms. To the extent that social relationships affect economic outcomes, it is illusory to consider wages to be solely determined by workers’ productivity (that is, their contribution to a firm’s output or added value)—all the more so because productivity is notoriously difficult to measure (Sauermann, 2016). The importance of wage bargaining suggests that social factors such as power resources, cultural beliefs and social norms are likely to also affect workers’ earnings (Lalive & Stutzer, 2010) and thus leave space for discrimination.

A first possibility is statistical discrimination. In this scenario, employers expect one group of workers (for instance, women with children) to be less dedicated to a job and hence less productive than another group (such as women without small children). Since measuring the work productivity of each individual is costly, employers simply decide to pay higher wages to workers from the group considered to be more productive, that is, women without children (Correll et al., 2007).

Another possibility is that the motherhood wage gap is driven by social norms. In this view, employers consciously or unconsciously favour one social group over another based not on the group’s expected work productivity but on their own cultural norms. The dominant social norm across much of the Western world considers mothers’ main role to be at home with their children, whereas their paid jobs appear of secondary importance (Alesina et al., 2013; Krüger & Levy, 2001). The opposite norm applies to fathers, whose main role is seen as being the family’s breadwinner, not the caretaker at home. Motherhood may thus be a status characteristic that yields lower social expectations about adequate wages (Auspurg et al., 2017).

Experimental Evidence on the Motherhood Wage Gap

It is a major challenge to empirically disentangle the influence of productivity from that of discrimination. Although panel surveys ask individuals detailed questions about their training, tenure and occupation, they do not measure all dimensions of work productivity, making it difficult to distinguish the influence of (unobserved) productivity from the influence of employer discrimination. For this reason, researchers have used experimental methods to test the hypothesis of discriminatory practices (Auspurg et al., 2017; Neumark, 2018).

Experimental evidence on the origins of the motherhood wage gap is scarce. An American study combines an experiment among students with an audit study among employers and shows that women without children are rated significantly higher than women with children in terms of competence, work commitment and promotion prospects—and also receive higher recommendations for hire. This difference is remarkable because their CVs are strictly the same in terms of productivity-related characteristics and differ only in respect to motherhood status (Correll et al., 2007). When asked to recommend a starting wage to fictitious applicants, the participants in the experiment offered women with children 7% less than women without children. Likewise, an additional audit study found that prospective employers called mothers back only half as often as childless women, whereas fathers were not disadvantaged at any stage of the hiring process (Correll et al., 2007).

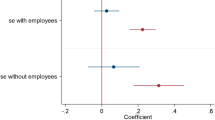

More recent empirical evidence for the motherhood wage gap stems from a factorial survey experiment in Switzerland (Oesch et al., 2017). Factorial surveys, also known as vignette studies, simulate the hiring process by presenting the résumés of fictitious job candidates to respondents and asking them for ratings. Randomly combining sensitive attributes such as age, gender, nationality or motherhood, these studies are less subject to desirability bias than conventional surveys. Moreover, the experimental setup makes it possible to eliminate unobserved heterogeneity (McDonald, 2020).

This factorial survey experiment obtained ratings from over 500 HR managers and thus specifically targeted individuals whose job was to recruit workers (Fossati et al., 2020). The results show that HR managers assign wages that are 2 to 3 percent lower to female applicants if they have children than to female applicants without children—the two groups being otherwise strictly identical. The wage penalty is larger for younger mothers and amounts to 6 percent for those aged 40 and under, suggesting that HR managers are wary of hiring mothers of small—and thus care-intensive—children (Oesch et al., 2017). This experiment not only confirms the findings by Correll et al. (2007) that employers offer lower wages to mothers than non-mothers, it is also consistent with the results of two national panel studies for Switzerland analysing how women’s wages evolve before and after the birth of children, showing a net wage penalty of between 4 and 8 percent per child (Oesch et al., 2017). These unexplained wage residuals are comparable to those found for Germany (Gangl & Ziefle, 2009) but clearly exceed those reported for the United States (England et al., 2016).

Country Differences in Social Policy

These country differences in the motherhood wage penalty have been attributed to differences in gender norms and government policies, such as taxes and transfers on the one hand and parental leave and public childcare on the other. These institutions crucially affect mothers’ options and incentives to take on paid employment (Kleven, Landais, Posch, et al., 2019).

Of particular interest is the institution of maternity leave. Governments may address the motherhood penalty on the labour market by offering care for young children through different forms of parental leave. Leave policies offer both parents time to care for the young child until the child is old enough for institutional childcare. In practice, it is overwhelmingly mothers who take parental leave, and only recently have Nordic countries seen some fathers following suit. As a result, mothers often remain the primary carers of their children, and employers continue to discount applications by mothers of young children.

Switzerland provides an ideal case for analysing the effect of leave policies, as it introduced mandatory federal maternity leave as late as 2005, making it one of the last member countries of the OECD to do so. It is possible to analyse the effects of this institutional change by contrasting women who gave birth in regions that already had cantonal leave policies in place and were thus not affected by the federal mandate with women living in regions that were affected by the federal leave policy. These analyses show some gains in terms of employment and earnings among mothers two to three years after maternity leave was introduced and a substantial increase in fertility (Girsberger et al., 2021).

Parental leave, which is taken after maternity leave, was substantially expanded in the 1990s in Austria. This expansion makes it possible to study how the length of leave affects the labour market outcomes of women who were eligible for either 12, 18, or 24 months of leave. The results suggest that there is no effect (Lalive et al., 2014). The same institutional setting also makes it possible to analyse how parental leave payments and/or the promise to keep the prebirth job affect leave taking. The results show that both features—parental leave payments and job promise—are needed for strong leave utilisation and swift reentry into the labour market (Lalive et al., 2014).

Childcare is important for a series of outcomes. A recent study in Germany examined the effects of a reform that massively expanded the availability of childcare places and found that those children who accessed care thanks to this reform strongly benefitted from it. Effects on socioemotional skills were strongly positive for those children who were able to be in care once their offer was expanded. Childcare notably helped children of immigrant parents as well as those with less educated mothers catch up with other children (Felfe & Lalive, 2018). Childcare thus seems to offer the greatest benefits to socioeconomically less advantaged families.

Conclusion

This chapter’s objective is to show how personal ties with family and friends crucially affect labour market outcomes, such as employment and wages. The importance of social relationships reminds us that markets are not self-contained systems populated by unattached and interchangeable individuals but social institutions that are embedded in local communities and shaped by noneconomic influences such as social norms and power relations.

Social connections may improve people’s ability to find and keep jobs. In this sense, social connections can certainly be seen as reserves (see Cullati et al., 2018). In fact, activating one’s personal connections has been advocated as a policy instrument in the presence of stressors such as job loss (Bonoli, 2014). However, the use of social networks in job searches can also have detrimental side effects in terms of both equity and efficiency. Equity is affected if better-connected individuals have easier access to better job opportunities and, more worryingly, if social connections become a precondition for access to certain positions, transforming the labour market into a nepotist regime. Efficiency may also be reduced if individuals with contacts in certain sectors and talents in others prefer easier job searches and choose jobs for which they do not provide an optimal match.

Crucially, the spillover effects between the social and economic life domains travel in both directions. Labour market behaviour is not only shaped by personal relationships but also, in turn, crucially affects these relationships. A prime example is how job loss affects the stability of partnerships. A large body of evidence shows that recessions reduce the divorce rate at the aggregate level: When material resources become scarce, the relative cost of separation increases and enhances couple stability (Amato & Beattie, 2011; Kalmijn, 2007). However, while divorce rates fall during recessions among couples who worry about the economy, those individuals who do lose their jobs are more likely to see their couples break up. In Germany and the United Kingdom, separation rates nearly double among couples in which one of the two partners experiences an unemployment period (Di Nallo et al., 2021). The social and economic spheres are intimately interconnected and understanding both is necessary to develop a complete picture of how employment outcomes affect relationships with family and friends, notably in terms of partnership stability and fertility.

Communal and work-related resources support and enable employment through the provision of information and emotional support, while employment and a stable economic outlook for the individual improve the stability of marital relations. The life domains of family and friends are thus linked with the life domains of employment and the labour market. Policy needs to take these links into account in order to improve the effectiveness of interventions.

Notes

- 1.

Among others, professors are kept busy by the writing of recommendation letters.

- 2.

An example for Switzerland 2019 is the Swiss Federal Railways paying their employees 2500 CHF (2000 €) for helping find new hires. See Basler Zeitung, “SBB suchen Personal—und zahlen 2500 Franken für Tipps”, 18. 7. 2019, https://www.bazonline.ch/sbb-suchen-personal-und-zahlen-2500-franken-fuer-tipps-826854363323.

- 3.

Note that almost 30 percent of individuals in Granovetter’s (1974) classic study, all of whom had recently changed jobs, denied having actively searched for new employment.

- 4.

Young women may already be discriminated against even before giving birth to a child because of employers’ anticipation of future family commitments. Identifying this “ex ante” discrimination is a challenge. Gruber (1994) analyses the introduction of mandates to firms to introduce benefits for mothers of young children, e.g., maternity leave. Maternity leave mandates have no effect on employment, but they reduce wages paid to young women compared to young men.

References

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for ‘Lemons’: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics., 84(3), 488–500.

Alesina, A., Giuliano, P., & Nunn, N. (2013). On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough. Quarterly Journal of Economics., 128(2), 469–530.

Amato, P. R., & Beattie, B. (2011). Does the unemployment rate affect the divorce rate? An analysis of state data 1960–2005. Social Science Research, 40(3), 705–715.

Arni, P., Parrotta, P., & Lalive, R. (2020). Are social networks an effective job search channel? Results from a randomized experiment. Mimeo, University of Lausanne.

Auspurg, K., Hinz, T., & Sauer, C. (2017). Why should women get less? Evidence on the gender pay gap from multifactorial survey experiments. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 179–210.

Bentolila, S., Michelacci, C., & Suarez, J. (2010). Social contacts and occupational choice. Economica, 77(305), 20–45.

Bonoli, G. (2014). Networking the unemployed: Can policy interventions facilitate access to employment through informal channels? International Social Security Review, 67(2), 85–106.

Bonoli, G., & Turtschi, N. (2015). Inequality in social capital and labour market re-entry among unemployed people. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 42, 87–95.

Calvo-Armengol, A., & Jackson, M. O. (2004). The effects of social networks on employment and inequality. American Economic Review, 94(3), 426–454.

Chua, V. (2011). Social networks and labour market outcomes in a meritocracy. Social Networks, 33, 1–11.

Corak, M., & Piraino, P. (2011). The intergenerational transmission of employers. Journal of Labour Economics, 29(1), 37–68.

Correll, S., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297–1339.

Cullati, S., Kliegel, M., & Widmer, E. (2018). Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life. Nature Human Behavior, 2, 551–558.

De Giorgi, G., & Pellizzari, M. (2014). Understanding social interactions: Evidence from the classroom. The Economic Journal, 124(579), 917–953.

De Giorgi, G., Pellizzari, M., & Redaelli, S. (2010). Identification of social interactions through partially overlapping peer groups. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 241–275.

Di Nallo, A., Lipps, O., Oesch, D., & Voorpostel, M. (2021). The effect of unemployment on couples separating in Germany and the UK. Journal of Marriage and the Family. Advance Access, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12803

England, P., Bearak, J., Budig, M., & Hodges, M. (2016). Do highly paid, highly skilled women experience the largest motherhood penalty? American Sociological Review, 81(6), 116 1-1189.

Felfe, C., & Lalive, R. (2018). Does early child care affect children’s development? Journal of Public Economics, 159, 33–53.

Forsé, M. (2001). Rôle spécifique et croissance du capital social. Revue de l’OFCE, 1, 189–216.

Fossati, F., Liechti, F., & Auer, D. (2020). Can signaling assimilation mitigate hiring discrimination? Evidence from a survey experiment. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 65.

Frank, K. A., Muller, C., & Mueller, A. S. (2013). The embeddedness of adolescent friendship nominations: The formation of social capital in emergent network structures. American Journal of Sociology, 119(1), 216–253.

Gamoran, A., Collares, A. C., & Barfels, S. (2016). Does racial isolation in school lead to long-term disadvantages? Labor market consequences of high school racial composition. American Journal of Sociology, 121(4), 1116–1167.

Gangl, M., & Ziefle, A. (2009). Motherhood, labour force behavior, and women’s careers: An empirical assessment of the wage penalty for motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United Sates. Demography, 46(2), 341–369.

Girsberger, E. M., Hassani-Nezhad, L., Karunanethy, K., & Lalive, R. (2021). Mothers at work in Switzerland: Impact of first paid maternity leave on mothers’ earnings and employment. Mimeo, University of Lausanne.

Glauber, R. (2018). Trends in the motherhood wage penalty and fatherhood wage premium for low, middle, and high earners. Demography, 55(5), 1663–1680.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380.

Granovetter, M. (1974). Getting a job. Harvard University Press.

Granovetter, M. (2005). The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives., 19, 33–50.

Gruber, J. (1994). The incidence of mandated maternity benefits. American Economic Review, 84(3), 622–641.

Kalmijn, M. (2007). Explaining cross-national differences in marriage, cohabitation, and divorce in Europe, 1990–2000. Population Studies, 61(3), 243–263.

Kleven, H., Landais, C., Posch, J., Steinhauer, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2019). Child penalties across countries: Evidence and explanations. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109, 122–126.

Kleven, H., Landais, C., & Søgaard, J. E. (2019). Children and gender inequality: Evidence from Denmark. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(4), 181–209.

Kramarz, F., & Skans, O. (2014). When strong ties are strong: Networks and youth labour market entry. The Review of Economic Studies, 81(3 (288)), 1164–1200.

Krüger, H., & Levy, R. (2001). Linking life courses, work, and the family: Theorizing a not so visible nexus between women and men. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 26, 145–166.

Lalive, R., Schlosser, A., Steinhauer, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2014). Parental leave and mothers’ careers: The relative importance of job protection and cash benefits. Review of Economic Studies, 81(1), 219–265.

Lalive, R., & Stutzer, A. (2010). Approval of equal rights and gender differences in well-being. Journal of Population Economics, 23(3), 933–962.

Lerner, J., & Malmendier, U. (2013). With a little help from my (random) friends: Success and failure in post-business school entrepreneurship. Review of Financial Studies, 26(10), 2411–2452.

McDonald, P. (2020). Family and employment: The impact of marriage and children on labour market outcomes. Doctoral dissertation, University of Lausanne.

Montgomery, J. D. (1991). Social networks and labor-market outcomes: Toward an economic analysis. American Economic Review, 81(5), 1408–1418.

Neumark, D. (2018). Experimental research on labour market discrimination. Journal of Economic Literature, 56(3), 799–866.

Oesch, D., McDonald, P., & Lipps, O. (2017). The wage penalty for motherhood: Evidence on discrimination from panel data and a survey experiment for Switzerland. Demographic Research, 37, 1793–1824.

Oesch, D., & von Ow, A. (2017). Social networks and job access for the unemployed: Work ties for the upper-middle class, communal ties for the working class. European Sociological Review, 33(2), 275–291.

Pellizzari, M. (2010). Do friends and relatives really help in getting a good job? ILR Review, 63(3), 494–510.

Sauermann, J. (2016). Performance measures and worker productivity. IZA World of Labor, 2016, 260.

Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics., 87(3), 355–374.

Stiglitz, J. E., & Shapiro, C. (1984). Equilibrium unemployment as a worker discipline device. American Economic Review., 74(3), 433–444.

von Ow, A. (2016). Finding a job through social ties. A survey study on unemployed job seekers. Doctoral thesis, University of Lausanne, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences.

Zenou, Y. (2015). A dynamic model of weak and strong ties in the labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(4), 891–932.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lalive, R., Oesch, D., Pellizzari, M. (2023). How Personal Relationships Affect Employment Outcomes: On the Role of Social Networks and Family Obligations. In: Spini, D., Widmer, E. (eds) Withstanding Vulnerability throughout Adult Life. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-4566-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-4567-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)