Abstract

Diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is a rare entity, more commonly seen in children as compared to adults. It is classified as congenital or acquired. Most common cause of acquired hernia is following trauma. Management of DH is primarily surgical repair which can be performed by laparotomy, laparoscopy, thoracotomy, or thoracoscopy. Due to the rarity of the disease, there is a paucity of data in the literature regarding the best approach for the repair. With the advent of laparoscopy or thoracoscopy, these are the preferred options as it offers us all the known benefits associated with minimally invasive surgery (MIS). For the scope of this chapter, our focus will be on the role of thoracoscopy and laparoscopy in the management of adult DH, the technical details, and its associated complications.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is a rare entity, more commonly seen in children as compared to adults. It is classified as congenital or acquired. Most common cause of acquired hernia is following trauma. Management of DH is primarily surgical repair which can be performed by laparotomy, laparoscopy, thoracotomy, or thoracoscopy. Due to the rarity of the disease, there is a paucity of data in the literature regarding the best approach for the repair. With the advent of laparoscopy or thoracoscopy, these are the preferred options as it offers us all the known benefits associated with minimally invasive surgery (MIS). For the scope of this chapter, our focus will be on the role of thoracoscopy and laparoscopy in the management of adult DH, the technical details, and its associated complications.

Introduction

An important muscle of respiration, the diaphragm forms a physical wall which separates the contents of the chest from the abdomen. In diaphragmatic hernia (DH), there is herniation of abdominal viscera into the pleural space through a weakness or defect in the diaphragm. The single most important factor is due to the pressure gradient between the abdominal and thoracic cavities. During respiratory cycle, this may reach up to 100 mm of Hg and contributes to herniation of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity [1]. DH can be classified as congenital or acquired [2]. Congenital DH is seen mainly in pediatric population and occurs due to failure of the fusion of foraminas of diaphragm. In Bochdalek hernia, there is an incomplete fusion of posterolateral foramina and in Morgagni hernia, it is at the anterior midline through the sterno-coastal region. Acquired DH is most commonly traumatic in origin, mainly due to penetrating or blunt trauma to the abdomen or thorax. Spontaneous DH is a rarity where the patient denies any history of trauma or symptoms and accounts for less than 1% of cases [3, 4]. But a possibility of a previously forgotten trauma cannot be ruled out completely. The presentation of DH can be acute or chronic. For chronic DH, the classification criteria concerns the temporal parameter of its development and diagnosis. As per Carter’s Scheme [5].

-

1.

Acute phase (time between the original trauma and the patient’s recovery)

-

2.

Latent phase (time post-recovery during which patient may or may not be symptomatic and obstructive phase)

-

3.

Obstructive phase (when contents become incarcerated with potential risk of ischemia, necrosis, and perforation)

The diagnosis of traumatic DH is often delayed as at the time of the accident or trauma it is difficult to detect a small defect or rent in the diaphragm [6]. Most symptoms are masked due to the associated symptoms from the traumatic injury [5, 7]. It only raises suspicion when complications of DH occur, e.g., gastrointestinal obstruction, strangulation of contents, or cardiopulmonary compromise. Traumatic DH is more common on left side (80%) and can be bilateral in 1–3% of cases. The left preponderance is thought to be due to the protective effect of the bare area of liver dissipating the force of the injury. The incidence of DH post penetrating trauma is almost double after a gunshot injury (20–59%) as compared to stab wounds (15–32%) [8]. Classically a chronic DH is a sequelae of an undiagnosed and untreated diaphragmatic injury while managing an acute traumatic event. Both penetrating and blunt thoracoabdominal injuries may cause a DH.

The clinical features of DH differ based on the location of the hernia and the organs herniating through it. Most common organs involved are the liver and gallbladder on the right side and the stomach, colon, and small bowel on the left side. In large hernia, solid organs like liver and spleen may also herniate. DH is often asymptomatic or produces very mild symptoms, till serious complications like obstruction or strangulation manifest. It is not unusual for the patient to present months to years after the index injury. Symptomatology may be related to respiratory tract, gastrointestinal organs, or a nonspecific general pain. When complications occur, patient may have severe respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular symptoms which may mimic a tension pneumothorax also.

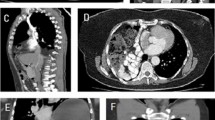

In some cases, a DH may be discovered incidentally on a radiological examination performed for unrelated reasons. A high index of suspicion is necessarily combined with a detailed history, thorough clinical examination, proper interpretation of the radiological images namely chest radiograph which is a preliminary investigation ordered in most outpatient or emergency setup. Usual findings are loss of diaphragmatic integrity with bowel haustrations or gas shadows within thorax, mediastinal shift to normal side, atelectasis, pleural effusion, or hydro-pneumothorax. If a nasogastric tube is inserted, very commonly this may be seen in the chest in defect on the left side if stomach has herniated through. A CT scan of chest and abdomen or MRI may be helpful when diagnosis is uncertain.

Once diagnosed, irrespective of symptoms it is advisable to offer surgery if the patient is fit. This can be via laparotomy, thoracotomy, laparoscopy, or thoracoscopy or a combined approach based on the surgeon’s preference, anatomic location of defect, degree of infra-diaphragmatic adhesions, and previous abdominal repair [9]. It is not advisable to delay the surgery as this may lead to complications, e.g., volvulus, incarceration, strangulation, etc. The goal is to reduce the contents back into the abdominal cavity and repairing the defect in the diaphragm. Minimal invasive surgery in the form of laparoscopy or thoracoscopy offers us all the benefits in terms of lesser pain, shorter hospitalization, reduced respiratory complications, and early return to work [3, 9]. Although data from randomized control trials is lacking results of both thoracoscopy or laparoscopy have been found to be comparable [9]. Laparoscopy in particular by delineating clear anatomy, better working space is increasingly thought to be a safe and feasible option to repair DH [10].

Acute DH with obstruction/strangulation or Acute traumatic DH: In an acute scenario, surgical approach should be immediate without any delay. Traditionally this would involve a laparotomy or thoracotomy. Use of prosthesis when contaminated field is present is debatable. Use of biological mesh may be considered. For the scope of this chapter, we would keep our focus on minimal invasive modalities.

Preoperative Work-Up

A thorough preoperative assessment is required to assess fitness to withstand the surgery, nutritional assessment, and optimization of medical comorbidities. This includes routine blood, urinalysis, chest radiograph, barium swallow if needed, or a CT scan. If a history of smoking is present it is advisable to abstain immediately. Acute presentation of DH is a true surgical emergency and we may need to proceed to surgery immediately. Correction of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities if any should be done. In left side hernias, it is advisable to decompress the stomach with nasogastric tube. Counsel the patient regarding the risk of complications with particular emphasis on recurrence.

Operative Technique: Laparoscopy

Theater layout and patient position: The patient is placed in supine position with split legs. Secure the patient safely to the operative table with straps at mid-thigh levels, to both legs separately and foot support if patient is morbidly obese. The stability should be tested preoperatively by placing patient in anti-Trendelenburg position before starting the surgery. The arms are tucked by the patient side. Compression stockings and pneumatic compression devices are applied to both legs until unless contraindicated. The surgeon stands in between the legs, camera operator on the right side, and another assistant on the left in left side DH. On right side DH, the camera operator and assistant change their positions. It is ideal to have two monitors one on either side of the patient’s head. If only one monitor is present place it above the affected side shoulder.

Abdominal access and techniques: Creation of pneumoperitoneum can be done using a Veress needle, by direct trocar entry (Optical entry) or open Hasson’s technique. Insufflating the abdomen to 12–14 mmHg. The table is then placed in anti-Trendelenburg position 25–300. This allows better visualization of the upper abdominal cavity and tissue spaces that need to be dissected. Rest trocars are placed under vision. A liver retraction device is placed through one of these port sites, usually substernal to retract the liver if it is not herniating. The port position and numbers vary slightly depending upon the side of the hernia. Total 4–5 trocars technique is used based upon the side of DH, the contents herniating through. On the right side DH, a 10/12 mm port just above the umbilicus for scope, two additional ports laterally on the right side one in the midclavicular line and another along the anterior axillary line, one additional 5 mm port in the midline epigastric region for assistant. For left side DH, five ports are generally used. A 10/12 mm port just above the umbilicus, two working lateral ports on either side in the midclavicular line at the level of umbilicus, 5 mm substernal port for liver retraction, and additional port left side laterally along the anterior axillary line for assistant.

Always start by performing a general examination of the peritoneal cavity to exclude any other pathology, e.g., other abdominal wall hernia, adhesions, or what organs are herniating to the defect (Fig. 1). Visualize the entire diaphragm on both sides and assess for contents of the DH.

Reducing the contents and delineating the defect: Use nontraumatic graspers to retract bowels caudally away from the operative field. Contents of the hernia are gently reduced using nontraumatic graspers (Fig. 2).

In acute cases the contents especially stomach, small bowel, or colon may be edematous and can be easily damaged with serosal tears or enterotomies. Special care is taken while handling and reducing solid organs, e.g., spleen if seen herniating to avoid hemorrhage. Any adhesions between the herniated organs and sac which are continuous with the pleural lining should be meticulously separated using an energy device as per surgeon preference. It is not uncommon to end up making multiple openings in the pleural lining. Any openings in the pleural lining can be sutured using 3–0 absorbable sutures. In difficult cases, a thoracoscopy may be performed additionally to aid the release of adhesions of herniated abdominal contents from the thoracic cavity. In longstanding DH, the lung on the affected side is hypoplastic in many cases. Once the defect is delineated, clear out any adhesions around the edges so as to gain space for suturing the edges and mesh placement/fixation. At this stage, if required one can pass an intercoastal drain under vision into the pleural cavity. In large defects this may involve mobilizing the splenic flexure on the left side, Gerota’s fascia or the triangular ligaments of the liver. In cases of large and redundant hernial sacs, excess sacs can be excised to facilitate proper closure. If eventration of diaphragm is present, we can plicate the diaphragm with polypropylene or ethibond sutures. The plication helps to bring the diaphragm to the desired level which will help us during defect closure.

Defect closure: With regards to defect closure, some surgeons prefer simple suturing of the defect, whereas others prefer to additionally reinforce the defect with prosthetic material. However, it is generally agreed that defects which are larger than 20–30 cm2 do require the use of prosthesis [11]. The author prefers the use of barbed suture or ethibond to close the defect. Meticulous defect closure is attempted in all cases (Fig. 3).

If required peritoneal flaps or muscular flaps can be utilized. In addition to providing a flat surface for prosthesis placement, it prevents mesh extrusion through the defect [12]. Once the defect is closed, different types of prosthesis can be used for reinforcement. In the literature review, polypropylene, composite mesh, and biological meshes have been used. In the authors opinion, composite or biological mesh should be used. Although more expensive, they are preferred due to lower infection rates and less risk of erosion into hollow viscus [13]. Like any hernial repair, the mesh should overlap the defect by at least 5 cm all around to reduce risk of recurrence. Until and unless contraindicated, we always reinforce the closed defect with a prosthesis to reduce the risk of recurrence. Also, placing the mesh on the peritoneal surface of diaphragm by physiology of intra-abdominal pressure keeps the mesh opposed to the defect (Laplace’s law). The mesh is then fixed using sutures, tackers, or glue (Fig. 4). While tackers are the most commonly used modality, it is advisable to use them carefully so as to avoid injury to vital structures in the vicinity.

Thoracoscopy: A thoracic approach may be preferred to treat recurrent diaphragmatic hernia, following a previous abdominal repair. It can also be used in combination with laparoscopy, especially in presence of dense adhesions between the contents and the thoracic cavity inner lining [14]. It is also easier to plicate diaphragmatic eventration thoracoscopically as compared to laparoscopically. If a thoracoscopic or laparo-thoracoscopic approach is planned it is advisable to perform general anesthesia with a double-lumen tube to achieve single-lung ventilation.

Postoperative Care

Patient who has preoperative respiratory distress (emergency scenarios) or a severely hypoplastic lung on affected side, recovery from anesthesia may be difficult and may need ventilatory support postoperatively. Similarly, in patients where bowel resection is performed, e.g., strangulation of contents, etc., may need nutritional support in the form of TPN or enteric feeding.

In elective setup, as per ERAS protocol (Early recovery after surgery) adequate analgesia and anti-emetics are prescribed. Early mobilization and feeds are encouraged. Postoperative anti-thrombotic prophylaxis based upon hospital recommendations should be followed. Anti-microbial cover is decided on a case-to-case basis. All patients should undergo a postoperative chest radiograph. Intercoastal drain is removed based upon the quantity of draining fluid from the pleural cavity, resolution of pneumothorax, and lung expansion. Regular follow up is needed, ideally after 1 week, every 3 months in the first year, and then annually for 4–5 years after surgery. A detailed clinical examination and chest radiograph should be performed.

Complications

Fatal intraoperative complications such as failure to return viscera to the abdominal cavity, irreparable bowel abnormalities, e.g., ischemia, gangrene, etc., failure to repair large defects, and difficulty maintaining ventilation and oxygenation ultimately leading to mortality are not uncommon particularly in emergency scenarios. Routine complications of any thoracoscopic or gastrointestinal surgery such as chest infection, wound infections, bleeding, incisional hernia, adhesions, and postoperative ileus are reported. While performing adhesiolysis, bleeding and visceral injuries can occur. Pneumothorax and pleural effusion are common complication. Longstanding DH predisposes patients to pulmonary hypertension. Although there is a paucity of evidence from randomized control trials, minimal invasive modalities of managing DH offer us all the benefits namely reduced pain, shorter hospitalization, early return to work, respiratory, and wound-related complications.

Recurrence: The incidence of recurrence is debatable. In congenital DH this ranges from 3 to 50% in various studies. It is advisable to repair a recurrent DH after a laparotomy or laparoscopy with thoracoscopic approach [15].

Bowel obstruction: Handling of intra-abdominal viscera invariably leads to adhesions, which may progress to bowel obstruction. These are more common after laparotomy as compared to laparoscopic DH repair [16, 17].

Long-term morbidity: Significant proportions of patients with longstanding DH suffer from long-term complications even after surgical repair. These are chronic respiratory disease, pulmonary hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and musculoskeletal deformities (more common after thoracotomy).

Conclusion

Minimally invasive surgery for DH repair offers us all the routine benefits such as magnified vision, shorter hospitalization, and reduced wound and pulmonary complications as compared to open methods. Laparoscopic or thoracoscopic repair of DH is a safe and effective method for managing adult diaphragmatic hernias, especially in experienced hands.

Practical Tips

-

Having a trained and regular team assisting during the surgery cannot be over-emphasised.

-

Combining laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a good option especially when adhesions are present between the contents and the thoracic cavity.

-

Insertion of additional trocars and conversion to open technique in difficult scenarios should not be considered as failure of surgery.

-

For defects closed under tension or defects larger than 10 cm use a prosthetic reinforcement.

-

In cases where the defect cannot be closed, local muscle flaps (intercostals, latissimus dorsi) or Intraperitoneal fascial flaps (Toldt’s) are performed to cover the defect with help of plastic surgeons.

-

Diaphragmatic hernia is a rare diagnosis. Surgical results are best in experienced hands. These are to be borne in mind before offering surgery to patients, especially in an elective setting.

References

İçme F, Vural S, Tanrıverdi F, Balkan E, Kozacı N, Kurtoğlu GÇ. Spontaneous diaphragmatic hernia: a case report. Eurasian J Emerg Med. 2014;13:209–11.

de Meijer VE, Vles WJ, Kats E, den Hoed PT. Iatrogenic diaphragmatic hernia complicating nephrectomy: top-down or bottom-up? Hernia. 2008;12(6):655–8.

Gupta S, Bali RK, Das K, Sisodia A, Dewan RK, Singla R. Rare presentation of spontaneous acquired diaphragmatic hernia. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2011;53(2):117–9.

Gupta V, Singhal R, Ansari MZ. Spontaneous rupture of the diaphragm. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12(1):43–4.

Carter BN, Giuseffi J, Felson B. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther. 1951;65(1):56–72.

Bani Hani MN. A combined laparoscopic and endoscopic approach to acute gastric volvulus associated with traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18(2):151–4.

Dwari AK, Mandal A, Das SK, Sakar S. Delayed presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with herniation of the left kidney and bowel loops. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2013;2013:814632.

Ahmed N, Jones D. Video-assisted thoracic surgery: state of the art in trauma care. Injury. 2004;35(5):479–89.

Saroj SK, Kumar S, Afaque Y, Bhartia AK, Bhartia VK. Laparoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in adults. Minimal Invas Surg. 2016;2016:1–5.

Thoman DS, Hui T, Phillips EH. Laparoscopic diaphragmatic hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(9):1345–9.

Jee Y. Laparoscopic diaphragmatic hernia repair using expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) for delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2017;12(2):189–93.

Palanivelu C, Jani KV, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Madhankumar MV, Malladi VK. Laparoscopic sutured closure with mesh reinforcement of incisional hernias. Hernia. 2002;11(3):223–8.

Esposito F, Lim C, Salloum C, Osseis M, Lahat E, Compagnon P, et al. Diaphragmatic hernia following liver resection: case series and review of the literature. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2017;21(3):114–21.

Chauhan SS, Mishra A, Dave S, Naqvi J, Tamaskar S, Sharma V, et al. Thoracolaparoscopic management of diaphragmatic hernia of adults: a case series. Int Surg J. 2020;7(5):1627–33.

Keijzer R, van de Ven C, Vlot J, et al. Thoracoscopic repair in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: patching is safe and reduces the recurrence rate. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(05):953–7.

Putnam LR, Tsao K, Lally KP, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia study group and the pediatric surgery research collaborative. Minimally invasive vs open congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: is there a superior approach? J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(04):416–22.

Davenport M, Rothenberg SS, Crabbe DCG, Wulkan ML. The great debate: open or thoracoscopic repair for oesophageal atresia or diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(02):240–6.

Acknowledgments

Kind regards to Dr. Sunil Kumar Nayak, Department of Minimal invasive surgery, GEM Hospital and Research Centre, Coimbatore for providing all the intraoperative images.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Salgaonkar, H., Marimuthu, K., Sharples, A., Rao, V., Balaji, N. (2023). Minimally Invasive Surgery for Diaphragmatic Hernia. In: Lomanto, D., Chen, W.TL., Fuentes, M.B. (eds) Mastering Endo-Laparoscopic and Thoracoscopic Surgery. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-3755-2_67

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-3755-2_67

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-3754-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-3755-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)