Abstract

A renewed sense of urgency has arisen around diversification in Arab oil-exporting countries, driven by a paradigm shift around the future prospects of global oil demand, and whether the oil industry will continue to generate sufficient rents into the future to sustain oil exporters’ economies and their extensive welfare systems. Regardless as to when oil demand will eventually peak, the current debate marks a break with history as it signifies a shift of perception from scarcity to abundance, which is already affecting the behaviour of all oil market players. In this chapter, we argue that the broader characteristics of the current energy transition, from hydrocarbons to low-carbon energy sources, are of greater relevance to economic diversification rather than when oil demand will peak. The diversification strategy adopted by oil-exporting countries will be conditioned by the speed of the transition, during which the oil sector will continue to play a key strategic role in these economies, as a means to diversification and generator of income. In a more competitive world, oil policy will continue to matter, and cooperation between producers will be imperative, yet challenging, as a cooperative strategy will be less effective in a carbon-constrained world. Although the global energy transition will influence diversification in Arab oil-exporting countries, the global transition itself will be influenced by the speed and success of diversification in these countries.

The authors are grateful to the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences for funding support.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Economic diversification has been a key developmental goal for the Arab oil-exporting countries since the 1970s, as evidenced in their various national development plans. Some have undoubtedly made progress over the last few decades in diversifying their economic base, but despite these efforts, several indicators of economic complexity, diversity and export quality continue to be lower in Arab oil-exporting economies than even in many emerging market economies, including commodity exporters in other regions (IMF 2016, 9–11).Footnote 1 For the Arab oil exporters, the biggest challenge has been to diversify the sources of government income (for instance, through raising additional revenues by taxing individuals and businesses) and to generate non-oil export revenues (through building export-oriented industries) (Luciani 2019; Shehabi 2019). Following the oil price fall in 2014, the weakening of macroeconomic indicators, deterioration in fiscal and current account balances and sharp decline in private sector activity indicate that government spending fuelled by oil revenues still remains the main engine for economic growth.

However, there is a renewed sense of urgency around diversification in these countries, driven by a paradigm shift around the future prospects of global oil demand, and whether the oil industry will continue to generate sufficient rents into the future to sustain oil exporters’ economies and their extensive welfare systems. There is a growing consensus that the pace of oil demand growth is likely to slow over time, eventually plateauing or declining, as efficiency improvements, technological advances, climate change and environmental policies and changing social preferences lead to substitution away from oil in its traditional sectors (such as transportation), which have historically driven oil demand growth (Dale and Fattouh 2018, 3). For example, the International Energy Agency predicts that even if oil prices remain within the range of $60–$70/barrel, net oil income across the Middle East oil exporting economies will not recover to the levels seen in 2010–2015. Without far-reaching reforms, this would translate into large current account deficits, downward pressure on currencies and lower government spending. The downside economic risk equates to a $1500 drop in average annual disposable income per person (IEA 2018b, 11).

The concept of ‘peak oil demand’ is gaining consensus, with many scholars, company executives and policymakers predicting an imminent peak, as soon as before 2030. Increased uncertainty about the prospects of global oil demand is already influencing the behaviour of all oil market players, including the international majors, National Oil Companies (NOCs) and oil-exporting countries—which are intensifying their efforts to diversify their economies and sources of income. Regardless as to when oil demand will eventually peak, the current debate matters as it signifies a shift of perception from scarcity to abundance. Consequently, the concepts of scarcity premiums, the effectiveness of rationing oil supplies in an inter-temporal framework and the idea that oil kept underground today will command a higher price in the future need to be critically assessed, especially in the light of the region’s massive reserves (Dale and Fattouh 2018). Fattouh et al. (2018, 19) highlight that this issue is far more serious for oil-exporting countries than it is for international oil companies—while for the latter, reserve to production ratios typically range from 8 to 10 years, for the former, they run into decades (e.g. 63 years for Saudi Arabia; 90 years for Kuwait).

Given these economies’ long-standing efforts to diversify, one might ask: what is different this time round? The renewed sense of urgency in fact constitutes a break with history—when the concern was mainly over the macroeconomic consequences of heavy dependence on a single export commodity with a highly volatile price—to the possibility that as demand slows down, global oil markets become increasingly competitive and oil industry margins decline, Arab oil exporters can no longer rely indefinitely on oil export revenues for their future economic prosperity. In the bigger picture, it is argued that the world is on the brink of an ‘energy transition’Footnote 2 in which hydrocarbons will eventually be substituted away in the global energy mix in favour of low or zero carbon energy sources, alongside a paradigm shift in energy technology, institutions and infrastructure (Fattouh et al. 2018, 5; Sovacool and Geels 2016).

Against this changing context, this chapter addresses some key questions: how soon can we expect ‘peak oil demand’ to occur? How are diversification efforts in key oil exporters linked to the ongoing global energy transition? Will the hydrocarbon sector play any role during the energy transition? And will the emergence of renewables as competitive energy source impact economic diversification strategies in these countries?

We make three main arguments in this chapter. First, the speed of the energy transition is highly uncertain and heavily driven by government policies, implying that it will vary across regions and be unpredictable on a global scale. Second, the diversification strategy adopted by oil-exporting countries will be conditioned by the speed of the energy transition, during which the oil sector will continue to play a key role in these economies, including in their diversification efforts. Oil producers will need to be far more strategic in developing their energy sector, including the renewables sector, and strengthening forward and backward linkages to help diversify their economies. Finally, there is a co-dependence between the success of diversification efforts in oil exporters and the global energy transition. While the transition is already shaping the political and economic situation of the Arab oil exporters, the success (or failure) and the speed at which Arab oil exporters transition to a more diversified and more resilient economies will shape the global energy transition.

The next section reviews the debate on peak oil demand and the energy transition, and Sect. 3 summarises their implications for oil-exporting Arab countries. Section 4 considers the role of the oil sector in economic diversification and energy transition, and Sect. 5 discusses the implications of this changing context for traditional cooperation between oil producers. Section 6 concludes.

2 The Energy Transition and Perceptions of Peak Oil Demand

The current debate on peak demand tends to be dominated almost entirely by the time or point at which global oil demand is expected to peak. Consequently, most analyses of peak demand contain a wide range of projections, some suggesting that it could peak around the mid-2020s and others expecting it to grow beyond 2040. Figure 5.1 depicts these variations based on projections published by organisations such as BP, International Energy Agency (IEA) and US Energy Information Administration.

The IEA 2018 New Policies scenario, for instance, predicts that global oil demand will grow by around 1 million barrels per day (mb/d) on average each year until 2025; thereafter, average annual demand growth slows to around 0.25 mb/d, but global demand does not peak before 2040. All of this growth occurs in developing economies, whereas demand in advanced economies drops by over 0.4 mb/d on average each year until 2040. In contrast, in its 2018 Sustainable Development Scenario, demand falls by 25 mb/d between 2017 and 2040 (IEA 2018c, 133–134). The IEA’s 2018 Oil Market Report, on the other hand, sees demand growing strongly until 2023 (expanding by 1.4 mb/d in 2018 alone), but its pace slowing down to 1 mb/d thereafter (IEA 2018a). BP’s 2018 Energy Outlook contains three differing scenariosFootnote 3 of which the Evolving Transition (ET) scenario envisages oil demand continuing to grow until the 2030s, and plateauing thereafter (BP 2018).Footnote 4 The Energy Information Administration (EIA) in its 2017 International Energy Outlook ‘reference case’ scenario sees oil demand growing from 95 m/d in 2015 to 113 mb/d by 2040, but in a ‘low oil price’ scenario reflecting abundant supplies, it projects higher demand (5.5 mb/d more than the reference case) by 2040 (EIA 2017). In 2018, the EIA published three different ‘side cases’ on demand, focusing in detail on the way in which different macroeconomic scenarios might play out in three major world regions (China, India and Africa) and postulating different impacts on world primary energy demand as a consequence. While a full discussion of the latter is beyond the scope of this chapter, it highlights the range of uncertainty around various peak demand projections and the multitude of variables affecting the same.Footnote 5

An obvious question that arises from the multitude of peak demand forecasts is as follows: what kind of a scenario should Arab oil-exporting countries be preparing for? While exercises in forecasting peak demand contribute towards providing a renewed motivation for diversification, they should not be the sole factor upon which these strategies are undertaken. This is because the speed of the energy transition matters. At the same time, the speed of the transition will also be influenced by the manner in which key actors in the energy sector, including the Arab oil-exporting economies, choose to respond to it. The risks associated with the energy transition may be felt by investors much faster than the timescale within which the transition is completed. For example, this could be because of government policy signals supporting new low-carbon energy technologies vis-à-vis hydrocarbons, which contribute to improving the future competitiveness of these technologies. Investors in the hydrocarbon sector may therefore adjust their current risk preferences in relation to new investment and operational decisions (Fattouh et al. 2018, 2).

The wide range of forecasts on peak demand allows us to draw some key observations to set the context of this discussion. First, the range of uncertainty is high. Peak demand forecasts are highly dependent upon their underlying assumptions. For instance, while the IEA’s New Policies scenario is based on government policies that have already been announced or implemented, its Sustainable Development Scenario assumes a tightening of climate and environmental policies that are sufficiently aggressive for carbon emissions to decline at a rate that is broadly consistent with achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement reached at COP21 in 2015 (Dale and Fattouh 2018, 4). However, many of the more ambitious commitments made by the countries that are likely to pose the largest share of rising emissions in the future (e.g. China and India) are voluntary rather than binding, and therefore partially dependent upon the resolve of policymakers to fulfil them.Footnote 6

It is also difficult to entirely discount the possibility of countries reneging on some of their commitments, as some governments have recently acquiesced to domestic political pressures and rising rhetoric around trade protectionism.Footnote 7 Another illustration of the complexity of assumptions around peak demand projections relates to the consensus that the majority of oil demand growth until 2040 will come from non-OECD Asia, on the back of rising incomes and car ownership. The EIA, for instance, has predicted that China’s use of liquid fuels for transportation could increase by 36 per cent from 2015 to 2040, while India’s use over that period could increase by 142 per cent (EIA 2017, 36). At the same time, most forecasting organisations also allow for a scenario in their forecasts which takes into account the impact upon transport oil demand of vehicle electrification, automation and shared mobility. These, in turn, entail very different sorts of impacts in different combinations. For instance, in its 2018 Energy Outlook, BP did not see electrification on its own impacting oil use in transport significantly. But automation—which reduces the cost of shared mobility by 40 to 50 per cent—was seen as having a bigger impact.

BP estimated that electric vehicles (EVs) would account for 15 per cent of about 2 billion cars on the road in 2040, but for 30 per cent of all passenger car transportation measured by distance travelled (due to the uptake in shared mobility). A prominent academic paper by Fulton et al. (2017, 15–29) estimated a 50 per cent reduction in energy use in transport in an automation-electrification-shared mobility scenario over an automation-electrification scenario, by 2050. On the other hand, the BP Energy Outlook predicted that oil use in transport would remain almost unchanged in 2040, from 18.6 mb/d in 2016, with gains from efficiency and electrification offset by a doubling of overall demand in car travel (FT 2018). These variations in forecasts from different organisations show that the confidence intervals around any peak demand forecast are likely to be large, reflecting the high uncertainty about the speed of the transition and the factors shaping the transition.

The second key observation is the possibility of not one, but multiple peaks. An important consideration while assessing peak demand scenarios is the ‘rebound effect’—that is, the premise that a peak in oil demand could cause oil prices to fall, triggering higher demand from consumers and a potentially more than one peak. For instance, the EIA in its 2017 Outlook predicted that in a ‘low oil price’ scenario, global oil demand in 2040 would be 4.5 mb/d higher than in the reference case, as low prices stimulate higher consumption (EIA 2017, 34). Dale and Fattouh (2018, 5) argue that this effect can lead to multiple peaks. Their examination of data on US oil and gasoline demand shows that US oil demand peaked in 2005, declining at an average rate of 1 per cent per annum over the next 8 years—but since oil prices fell in 2014, US demand has begun to grow again, and a continuation of low pricesFootnote 8 could result in US demand exceeding the 2005 peak.Footnote 9 The ‘rebound effect’ is also evident in past energy transitions, in which new energy sources have unlocked new energy demand. For instance, Fattouh et al. (2018, 8) argue that the advent of coal in the nineteenth century opened up new forms of transportation, and its first use in the steam railway engine around 1829 was followed by an acceleration in global energy demand that was 1 per cent per annum higher than that of global population growth for nearly 50 years thereafter.

The third key observation that can be drawn from the range of peak demand forecasts is that oil will continue to be an important part of the energy mix for the foreseeable future. The incumbent advantages of oil as an energy source, including its high energy density and an existing infrastructure ecosystem geared around it, imply that even if oil demand peaks, it is unlikely to ‘fall off a cliff’. Instead, the broader characteristics of the current energy transition from hydrocarbons to low-carbon energy sources and the speed of transition are of more relevance to economic diversification, rather than predictions of when oil demand will peak. But while there is unlikely to be a sharp discontinuity in oil use, it is also unlikely that the current transition will exactly mirror the speed of past transitions, as it has some fundamentally different characteristics.

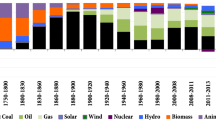

Historical data and evidence indicate that past energy transitions have been slow. Fattouh et al. (2018, 10) state, for instance, that fast transitions have rarely happened, and, when they have, they have been anomalies that are related to countries or specific contexts with little scope for replicability.Footnote 10 The scale and complexity of energy transitions tend to create path dependency and ‘lock-in’ of infrastructure that has been developed over long periods of time. Energy transitions also involve ‘fighting’ against an entire infrastructure ecosystem based on the incumbent energy source which represents massive sunk investments—this is visible, for instance, in efforts to substitute internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) with EVs. Fattouh et al. (2018, 10) show that the key empirical evidence for a slow transition is past inter-fuel competition, which led to the substitution of coal for pre-industrial biomass and muscle power, and oil for coal. The market share of coal increased from 5 per cent to 60 per cent between 1830 and 1914, peaking in the year that the First World War broke out. Oil increased from 1 per cent to 40 per cent between 1900 and 1973, peaking in the year of the first OPEC oil shock (2017). Gas increased from 4 per cent in 1945 to 24 per cent in 2018, while nuclear rose from zero per cent in 1954 to 2 per cent in 2000. There are also very few examples of major energy sources disappearing from the global energy mix. BP’s 2018 Energy Outlook, for instance, sees most oil demand growth after the 2030s coming from non-combustible uses, although this could also face a slowdown if measures to curb environmental pollution from materials (e.g. plastics) are tightened/enforced.

However, the possibility of a fast transition cannot be entirely discounted either, as the current transition bears characteristics that represent a clear break with the nature of past transitions. Historical transitions were more about developing technologies in an age of scarcity based on markets and innovation, whereas low-carbon transitions are more about adjusting the environmental selection in an age of abundance, via policies, regulations and incentives (Sovacool and Geels 2016). Therefore, while past transitions were opportunity-driven, the current transition is solution-driven. At the same time, since the current transition is heavily driven by government commitments on mitigating their emissions and consequently by national policies, its speed could differ across regions as well as sectors, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions on a global scale.

The discussion therefore underscores the futility of adopting an approach whose starting point is ‘oil will no longer be demanded by a certain date’, or, in other words, preparing for some ‘distant future’. Instead, it is necessary to adopt a more dynamic analysis that moves beyond the potential role that the oil sector and oil rents would play in the transition phase.

3 The Implications for Arab Oil-Exporting Countries

How should Arab oil-exporting countries respond to this changing context? The aforementioned discussion suggests that, on balance, oil-exporting countries should adapt to the energy transition which is already underway, but given that the speed of the transition is uncertain, in doing so they could take into account the consolidation of three key trends.

3.1 Oil Demand Is Unlikely to Increase Strongly Over the Next Two Decades

Government oil substitution policies point in the direction that oil demand is not likely to increase strongly over the next two decades, although the timing of when oil demand growth will start slowing down and turn negative is still highly uncertain. These policies are prevalent in OECD and non-OECD countries. Some countriesFootnote 11 in OECD Europe have for instance announced bans on ICEVs by 2040 as part of their carbon reduction targets which are among the world’s most ambitious, while in non-OECD Asia, China and India have both announced ambitions to scale up EVs in the vehicle fleetFootnote 12—with China attempting to integrate the EV sector into its overall industrial strategy. The two countries also have localised (state or province level) restrictions on ICEVs, through lottery sales and bans of older models. Further, both countries are moving towards the adoption of stricter fuel-efficiency standards by the early 2020s.Footnote 13 The drive to reduce urban air pollution could also accelerate substitution. The ‘ET’ scenario in BP’s 2018 Energy Outlook sees China’s energy demand growing by just 1.5 per cent per annum (less than a quarter of its historical 20-year growth rate), with renewables overtaking oil to become the largest energy source by 2040. India, on the other hand, is seen as overtaking China as the main engine of oil demand growth, although it remains smaller in terms of absolute volumes consumed. This trend has implications for future market share strategies of the Arab oil exporters, which should be taken account of in their diversification strategies.

3.2 Large Investments Will Still Be Needed in the Oil Sector to Fill the Gap in Supply

Even in the event of peak demand and in the absence of investment in the oil sector, the decline in supply will be faster than the decline in oil demand. Dale and Fattouh (2018, 5), in their analysis of peak scenarios for instance, assume a relatively conservative 3 per cent decline rate in production and no new investments until 2040Footnote 14 to illustrate that the gap between demand and supply could range from anywhere between 35 mb/d and 75 mb/d.Footnote 15 The IEA (2018c) estimates a near-term supply deficit of 26 mb/d by 2025 even under the Sustainable Development Scenario. Upstream investment has not recovered since the 2016–2017 oil price fall; it was flat in 2017, with a modest rise in 2018 mainly from USA’s use of light tight oil (Fattouh et al. 2018, 7). A survey by Fattouh et al. (2018) indicates that risk preferences of institutional investors (mainly in the USA and Europe) are already changing in response to the energy transition, reflected in much higher ‘hurdle rates’ required by investors now, relative to the last few years, to consider new long-term investments in oil exploration and development projects. Instead, there is a strong preference to concentrate oil and gas companies’ conventional activities in the ‘harvesting’ phase and away from the ‘exploration and appraisal’ phase.

As the world’s lowest-cost oil producers, Arab oil-exporting countries will most likely be required to fill this gap, but any expansion in productive capacity will require massive investments running into billions of dollars. These investments in productive capacity will need to be funded by sufficient revenues, largely from oil exports. At the same time, Arab oil producers face competing needs on their revenues given the social welfare measures funded by these revenues, which underpin their societies. Thus, although the physical cost of production and developing their reserves is low, one should add some measure of social costs in addition to the physical cost, as producers need higher prices for their economies to function and to expand productive capacity.Footnote 16

Countries also require relatively stable political environments to make these investments. In the absence of such stability, it is possible that some countries with cheap reserves will be unable to develop these reserves. In other words, it is not necessarily true that low-cost producers will develop their reserves at the expense of high-cost producers with more stable environments. In the long run, as economies diversify, the ‘social costs’ of production embodied by the fiscal breakeven price should naturally decline as economies are supported by a broader economic base (Dale and Fattouh 2018, 8). The major caveat to this point is that if climate change emission reduction policies lead to a fall in oil demand at the same pace as, or faster than, production declines from existing fields, then there would be no supply-demand gap (Fattouh et al. 2018, 7). The realisation of a constrained oil demand trajectory however depends on how determined policymakers in the developing world are (especially China and India) about moving away from fossil fuels—which we have discussed earlier in this chapter.

3.3 Renewables Are at an Inflection Point

While there are many uncertainties induced by the energy transition, there is almost a consensus among forecasts provided by various organisations that the share of renewables in the energy mix will rise (Fig. 5.2). As described in Fattouh et al. (2018, 4), renewable energy’s recent cost deflation has been nothing short of revolutionary for the global energy industry. Five years ago, US wind costs were $11 c/kWh (US cents per kilowatt hour) and solar costs were $17 c/kWh, on a fully loaded basis, including the capital costs of construction. Neither was commercial without subsidies. In 2019, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimated that solar PV costs in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) had declined to less than $3 c/kWh, leaving behind natural gas, LNG, coal, oil and nuclear. In Saudi Arabia and Oman, wind has emerged as another cost-effective option. The four bids submitted for the 400 MW Dumat Al Jandal wind project were reported to be between 2.13 US cents/kWh and 3.39 US cents/kWh (IRENA 2019, 86).

As a result, on a plant-level basis and excluding the cost of dealing with intermittency, wind and solar have emerged as very competitive sources of energy globally (Fattouh et al. 2018, 4). The 2018 BP Energy Outlook stated that the share of power generation gained by renewables over the Outlook period will be faster than any other energy source over a similar period—it saw renewables increasing fivefold and capturing 40 per cent of new demand growth (BP 2018). The EIA’s International Energy Outlook 2017 similarly saw renewables as the fastest growing source of overall energy consumption and power generation in 2015–2040—renewables will more than double their share in energy consumption by 2040, with their share in power generation rising by an average of 2.8 per cent a year and reaching over 30 per cent by 2040, as technological improvements and government incentives in many countries support their increased use.

In the next section, we discuss how the aforementioned three trends feed into an economic diversification agenda for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) which makes far more strategic use of the oil sector as the energy transition progresses, rather than one that simply envisages a sudden ‘switch’ away from oil and the redundancy of the oil sector.

4 The Strategic Role of the Oil Sector in the Energy Transition

As low-cost producers with some of the largest reserve bases, Arab oil producers are expected to fill the gap by heavily investing in their oil sector. Therefore, even in a world where oil demand growth is expected to slow down, the oil sector will continue to play the dominant role in these economies for the foreseeable future. However, as leaders develop new visions to transform their countries, the energy sector will be under increasing pressure to show that it can contribute to the diversification efforts, not only by generating the rents that could be used to create new industries and sectors, but also by extending the value chain and creating new industries within the energy sector through fostering backward and forward linkages. In the following section we discuss three important elements of this strategic role, which complement each other.

4.1 The Oil Sector Will Continue to Dominate the Economy, But it Needs to Play a More Active Role in the Diversification Process

Although the oil sector remains very profitable and enjoys higher margins than any new industries that government are aiming to establish, from a developmental perspective, it suffers from two major shortcomings. First, it does not generate a stable source of income as oil prices fluctuate considerably, and in some countries the rents are not big enough to provide sufficient income for growing populations and an extensive welfare system. In a world where demand is expected to peak, these challenges become more acute. Second, the oil industry is capital-intensive in nature and does not generate enough jobs for the hundreds of thousands entering the labour market each year.

Extending the value chain beyond simply producing crude oil and exporting it to international markets could in principle address some of these challenges. The Middle East currently accounts for around 10 per cent of global refinery runs, and countries are increasingly looking at petrochemicals projects as well as refinery expansions as a way of pursuing higher and more resilient margins. By extending the value chain, Arab oil producers can create new industries with different types of jobs and whose products’ prices are not highly correlated with oil prices. In the past, the focus has been on exporting basic petrochemicals (for instance, converting ethane to ethylene), which did not generate much of the expected benefits for two reasons. First, the prices of basic petrochemical products are highly correlated with oil prices. Second, refining and petrochemicals are also highly capital-intensive industries and do not generate many jobs. Therefore, the recent emphasis in some of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries has been on extending the value chain to more complex petrochemical products and even finished products manufactured in industrial parks that attract the private sector and foreign direct investment. The move towards non-combustible uses of oil also offers a degree of hedging against the possibility of a drop in oil demand (IEA 2018b).

For instance, Saudi Arabian Oil Company and Dow Chemical established a joint venture in 2011, with an investment of $20 billion, which incorporates 26 integrated large-scale manufacturing plants with over 3 million metric tonnes of capacity per annum. It has introduced many new products to Saudi Arabia (e.g. the first isocyanates and polyurethane plants), enabling many industries for intermediate products that either did not exist in the Kingdom or only existed through imports of raw materials, potentially opening up a range of new downstream opportunities. The Saudi Arabia Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC) has similarly established a number of industrial parks specialising in intermediate raw material inputs and offering easy access to banking facilities, research resources, skilled workforce, logistic services and other inputs—it has a particular focus on the automotive industry which offers opportunities down the value chain.

According to the IEA (2018b), Middle East chemicals production is expected to double between now and 2040—allowing the region’s share in global chemicals production to increase by four percentage points, reaching 17 per cent by 2040 on the back of feedstock cost advantage and the high level of efficiency of newly built facilities. A corollary of this increase in downstream activity is that, out of a 6.5 mb/d incremental increase in oil supply until 2040 from the region, only 800 kb/d is exported as crude (with additional 2.1 mb/d passing through refineries and 3.6 mb/d being used in petrochemicals production). Adding more stages to the oil value chain in this way generates not only more jobs, but also different types of jobs including jobs in the service sector such as trading, marketing and sales, procuring and logistics, as well as supporting services such as accounting, finance and human resource management.

In this respect, the local content requirements (LCRs) that give priority to nationals in terms of employment, domestic companies in terms of contracts and locally produced goods and services will only increase in importance. The objectives of such policies are to create a level playing field of local industries, create jobs for locals and enhance transfer of technology and technical expertise and skills. However, experience shows that such policies, if not properly implemented, can have unintended consequences such as increasing the cost of projects, misaligning the interests between the government and investors and hence dis-incentivising private investment and even encouraging corruption.

Arab oil producers, as owners of large low-cost resources, have rationed their supplies in order to preserve their resources for future generations—a strategy which made sense during the age of scarcity (Dale and Fattouh 2018). However, in carbon-constrained world, the main challenge for these producers in addition to maintaining the high levels of revenues upon which their economies are dependent is to monetise their massive reserve base in order to avoid to a greatest extent the possibility that significant amounts of recoverable oil may never be extracted.Footnote 17 This requires that Arab oil exporters play a key role in providing low-carbon solutions through developing and investing in low-carbon technologies that could extend the life of oil and gas.

Thus, rather than treating the oil industry as sunset industry in a world of heightened uncertainty about the prospects of oil demand, these countries will need to be much more strategic in terms of how the oil sector can further contribute to economic diversification. While the oil sector will continue to play a key role and to generate most of the income during the transition, it is expected to play a bigger role in the diversification and the economic transformation agenda. Business as usual for the oil sector and those who are leading it is no longer an option. Particularly, its success in extending the value chain and effectiveness in implementing LCRs will determine the weight the sector plays in the decision-making process and in influencing the transition. But, as noted by Fattouh and Shehabi (2019), the extent to which the energy sector can play such a role depends on governments removing a wide array of structural barriers such as reducing the role of the public sector in employment generation and capital employment, diversifying the sources of income through serious tax reform and dismantling the oligopolistic market structure. After all, ‘the real problem lies in the economic and political structures and in policies surrounding the energy sector; these factors not only constitute barriers to meaningful diversification, but also limit this sector’s contribution to broader and deeper diversification’ (Fattouh and Shehabi 2019).

4.2 The Use of Demand-Side Measures to Optimise the Resource Base

In addition to building new production capacity, these countries need to undertake other measures to optimise the use of the resource base. These include policies such as diversifying the energy mix and implementing energy efficiency measures and pricing reforms that liberate hydrocarbons that are currently used to meet soaring domestic demand at low (subsidised) prices for export, which would add economic value (as long as the international price is above the fiscal breakeven price). Across the Middle East, for example, a 5.7 per cent annual increase in electricity demand has translated to a doubling in the region’s oil consumption for power generation over the last 20 years, reaching around 1.8 mb/d in 2017 (IEA 2018b). This necessitates the implementation of energy-efficiency measures including subsidy reforms or price incentives. Indeed, subsidy reforms implemented in the GCC following the oil price fall of 2014–2016 have largely continued despite the price recovery in 2018. Further, such measures are complementary to an overall economic diversification strategy, which entails structural changes and fiscal reforms. For instance, the fact that all GCC countries (with the exception of Kuwait which has faced hurdles) have implemented energy pricing reform, constitutes an important step towards meaningful economic diversification in the long term.

Matar et al. (2017), for instance, explore the impact upon energy demand of various alternative policies to induce a transition to a more efficient energy system in Saudi Arabia, including immediately deregulating industrial fuel prices, gradually deregulating fuel prices and introducing investment credits or feed-in tariffs for efficient fuels. They find that the alternative policies result in nuclear and renewable technologies becoming cost-effective and producing 70 per cent of the Kingdom’s electricity in 2032 in contrast with hydrocarbons at present. They can also reduce the consumption of oil and natural gas by up to 2 million barrels of oil equivalent per day in 2032, with cumulative savings of 6.3 to 9.6 billion barrels of oil equivalent. They estimate a net economic gain up to half a trillion US dollars from increased oil exports, even with investments in nuclear and renewables. However, given the rigidity of existing political structures, institutions and the implicit social contract through which limited political participation is compensated for by distribution of hydrocarbon rents, gradual and small-scale reforms combined with mitigation measures can be implemented, but one should also not expect ‘speedy transformations’ of oil-exporting economies (Fattouh et al. 2018, 21).

4.3 Renewables as a Complement to Economic Diversification Strategies

Middle Eastern and in particular GCC oil exporters should not miss on the renewable ‘revolution’. They have great potential for renewable energies, owing to high levels of irradiation throughout these countries, and wind potential in some. Many countries in the region also have fewer limitations on the use of land for construction of wind and solar farms. Furthermore, their locations are often close to the regions’ main energy markets. Collectively, these conditions create a unique opportunity for these countries to exploit their renewable resources to their full potential to serve rising domestic demand, whilst also harmonising with the changing global energy landscape in which renewables are fast becoming mainstream (Poudineh et al. 2016, 6). At present, this potential is almost untapped, with the 1.2 GW of solar capacity making up less than 0.5 per cent of total generation capacity in the Middle East (compared to over 90 GW of oil-fired capacity) (IEA 2018b).

However, given the uncertainty in the speed of transition, Arab oil exporters need to adopt a strategy that is likely to be successful under a wide set of future market conditions (Fattouh et al. 2018, 4). Renewables may replace hydrocarbon resources in the domestic energy mix, but not immediately in the government budget, because investments in renewables still do not generate the high returns that the oil and gas industry does. Furthermore, while the renewable energy industry is part of the diversification strategy, it alone cannot deliver the real needs of these economies, such as job creation and welfare improvements.

Therefore, these countries need to gradually ‘extend’ their energy model rather than completely ‘shift’ from hydrocarbons to renewables and integrate renewables into their hydrocarbon assets (i.e. oil-exporting countries cannot simply ‘transform’ into renewable exporting countries) (Fattouh et al. 2018, 4–5). Indeed, these countries have unique characteristics that make the rationale of investment in renewables for them quite compelling. These countries have rising energy demand and are at a stage of development where economic growth is tied up with energy consumption. The rise in energy demand is expected to strain the export capability of these countries. Countries such as Kuwait and the UAE are already net importers of natural gas. Investment in renewables could help boost the short-term revenues of oil-exporting countries as it frees up their hydrocarbon resources for export (as long as international prices are above the breakeven price).Footnote 18 In short, for Middle Eastern oil exporters, investment in renewables addresses, to some extent, the government’s short-run revenue maximisation objective by freeing exports of hydrocarbons, but does not guarantee their long-term sustainability. In the long run, diversification of their economies remains the main adaptation strategy that these countries need to pursue (Fattouh et al. 2018, 21).

5 The Role of Oil Policy and Producer Cooperation

While diversification should remain the ultimate objective of Arab oil-exporting countries, the process is complex and fraught with challenges and potential setbacks and requires broad and deep structural reforms. Many oil producers may take a long time to develop alternative industries and activities that are as profitable as extracting low-cost oil. During the transition, the oil sector will continue to generate most of the income and therefore in addition to diversification, the oil exporting countries should aim to maximise the income from their hydrocarbon assets. This implies that oil policy and oil monetisation strategies will remain key in shaping these countries’ economic strategies for the foreseeable future.

Faced with the possibility of significantly lower oil demand, some suggest that these countries have no option, and indeed it is even rational that they monetise their reserves as quickly as possible and squeeze out high-cost producers and gain market share—just as with any other competitive market. However, this argument ignores the significant challenges that a shift to a competitive market poses for major oil-producing countries. If most low-cost producers adopt a similar strategy and increase supplies in the face of expected slowing demand growth, this will result in massive fall in oil prices and oil revenues, putting the political, social and economic stability of these countries at risk and derailing the entire economic diversification agenda. In other words, the heavy reliance on oil revenues places a constraint on how fast Arab oil exporters can shift to a more competitive world where prices converge to the marginal cost of physical production. There is also the question as to whether low-cost producers can sharply increase their production capacity, especially in an environment of low oil prices. This is a major undertaking, which requires huge investments, and cannot be implemented in countries with unstable political and economic environment.

This discussion implies that even as we shift to more competitive markets, oil policy and managing producer-producer relations will continue to matter. Rather than simply pursue a policy of non-cooperation and competition with low- and high-cost producers, it is most likely that producers would continue to cooperate and restrain their output in an attempt to maximise revenues. This is despite the fact that the challenges for producers pursuing a cooperative approach are immense, especially in a more competitive oil market.

To start with, the existing framework for cooperation is not well developed to deal with producers with different revenues needs and different degree of financial resilience. It also requires that producers constantly manage the market, based on newly developed criteria. Further, any cooperative action must go beyond output to include long-term investment plans; rapid investment and bringing on new capacity beyond what is needed in the market create problems similar to the high-output/low-price strategy. With many countries within OPEC and non-OPEC having ambitious plans to increase productive capacity, coordination on investment will be extremely difficult, if not impossible. Also, stabilising expectations around a higher oil price will not only encourage US shale producers to increase output, but would also encourage investment in the long-term capital-intensive cycle (Curtis and Montalbano 2017). Above all, long-term cooperation requires unprecedented exercise of leadership to maintain the coalition among producers during good and bad times.

All these issues suggest that maintaining cooperation in a more competitive world is very challenging, and while producers have the incentive to cooperate, the cooperation between producers has to take a different shape to what has existed in the past. For instance, producers should not only be concerned with low oil prices, but also be proactive when prices are too high, as high oil prices induce strong supply and demand responses and speed up the energy transition.

The cooperative solution, which results in a higher oil price, is also not without its costs, and those costs need to be managed by ensuring that prices don’t rise too high. It is also true that this cooperative strategy will be less effective over time in a carbon-constrained world. However, this does not imply that cooperation is not possible or sustainable for a prolonged period: as long as these economies are not diversified, the alternative of non-cooperation is also not sustainable. In a world where the prospects of oil demand and the speed of energy transition are highly uncertain, the immediate benefits from pursuing cooperation are more visible and certain than the benefits of pursuing the alternative strategy of fast monetisation of reserves.

Finally, it is worth stressing the co-dependence between diversification in oil exporters and the global energy transition. The transition is already shaping the political and economic outcomes in the Arab oil exporters, but the transition in the major Arab oil exporters to a more diversified and more resilient economies will also shape the global energy transition. In other words, this is a two-way street. If the transition in Arab countries does not go smoothly and countries fail in their diversification efforts, this could result in lower investment in the oil sector, output disruptions and more volatile oil prices. Also, in the absence of diversification, oil exporters will continue to push for higher oil prices. These have the effect of speeding up the global energy transition (Fattouh et al. 2018, 21). In contrast, if these countries succeed in their diversification objectives, they will not only increase the resilience of their economies, but this would allow them to pursue a more flexible and proactive oil policy and adopt long-term strategies that could influence the speed of global energy transition and secure long-term oil demand.

6 Conclusions

This chapter has added context to the debate on economic diversification by analysing it against the key arguments around peak oil demand and the energy transition. While exercises in forecasting peak demand contribute towards providing a new motivation for diversification as compared with the past, they should not be the sole factor upon which these strategies are undertaken. The starting point of any analysis of the Arab oil exporters should not be based on an approach solely predicated upon the timeline within which ‘oil will no longer be in demand’. Instead, it should take into account the consolidation of three key trends: first, that the range of uncertainty surrounding peak demand is high, and the speed of energy transition is highly uncertain and will not be uniform across the world. Second, that a single peak is not a certainty, particularly when taking into account the possibility of rebound effect. And third, that although an energy transition may be in progress, it is difficult to assume that the transition will result in a sudden and sharp discontinuity in oil demand, implying that oil will continue to be an important part of the energy mix (including in non-combustible uses) for the foreseeable future and that the oil sector will continue to play a key role in oil exporters’ economies.

The broader characteristics of the current energy transition from hydrocarbons to low-carbon energy sources are of more relevance to economic diversification rather than predictions of when oil demand will peak. In this regard, although there is unlikely to be a sharp discontinuity in oil use, it is also uncertain whether the current transition will exactly mirror the slow speed of historical transitions which were more about developing technologies in an age of scarcity based on markets and innovation, rather than being problem- and policy-driven.

The diversification strategy adopted by oil-exporting countries will be conditioned by the speed of the transition, which could be decades, during which the oil sector will continue to play a key role in these economies, both as a means to diversification (for e.g. extending the value chain beyond simply producing crude oil and exporting it to international markets) and as a generator of income. Arab oil producers will at the same time need to adopt complementary cost-effective strategies to optimise the use of their resource domestically to increase hydrocarbon exports. These strategies include taking advantage of the ‘inflection point’ in renewables, which has made renewable technologies competitive to liberate hydrocarbons used in the domestic economy at subsidised prices, for export, as well as adopt demand-side measures to encourage more efficient energy use. These are more cost-effective strategies than simply increasing productive capacity, which is costly and requires massive investments.

At the same time, Arab oil exporters will need to be far more strategic in their use of the oil sector to diversify their economies. In a more competitive world, oil policy will also continue to matter; cooperation between producers will be imperative, yet challenging, as a cooperative strategy could be less effective in a carbon-constrained world. The global energy transition will not only shape the political and economic outcomes in the Arab oil exporters, but the transition in the major oil exporters and the key choices they make will also shape the global energy transition.

Notes

- 1.

Recent measures include the Economic Complexity Index which measures the number of products made by an economy and controls for the likelihood that the same product is also made by others, IMF Export Diversification Index which is a combined measure of the ‘extensive’ and ‘intensive’ dimensions of diversification using trade data, IMF Export Quality Index which measures the average quality within any product category and Manufacturing Value-Added Gini which is constructed based on the relative value-added of different manufacturing industries within an economy (IMF 2016, 9–11).

- 2.

Previous energy transitions have involved wood being substituted by coal, and coal being substituted by oil on a mass basis.

- 3.

Evolving Transition (ET), Faster Transition (FT) and Even Faster Transition (EFT).

- 4.

Demand in 2040 is projected at 109 mb/d.

- 5.

Refer to EIA (2018) for a full discussion.

- 6.

We state that thats is partially dependent, as stringent environmental policies in developed countries have encouraged innovation, driving down the costs of clean energy technologies to make them cost-competitive on a global basis.

- 7.

For instance, the USA pulled out of the Paris Agreement in June 2017, although the consensus is that this will not derail the Agreement between the remaining signatories.

- 8.

This was not evident at the time of writing.

- 9.

US gasoline consumption reached its highest ever level in 2016 after falling for much of the previous 10 years.

- 10.

Examples of fast transitions include Sweden’s shift to efficient lighting in nine years; Indonesia’s substitution of kerosene with LPG in 3 years; Brazil’s substitution of petroleum with ethanol in 90 per cent of all new vehicles in six years (Fattouh et al. 2018, 12).

- 11.

The UK and France, for example.

- 12.

For instance, India is targeting 30 per cent of the vehicle fleet by 2030.

- 13.

India plans to leapfrog from Euro IV to Euro VI standards by 2020.

- 14.

We also show this in Fig. 5.1.

- 15.

The lower bound represents the difference between projected production (assuming the 3 per cent decline rate) and projected demand in 2040 under the IEA Sustainable Development Scenario, while the upper bound represents the difference with projected demand in 2040 under the EIA’s scenario.

- 16.

In the age of abundance and greater competition, prices would ideally tend towards marginal cost, but MENA producers require a premium to finance their socioeconomic models.

- 17.

In other words, that countries are not effectively left with ‘stranded assets’.

- 18.

The economics of renewables in exporting countries depends on the opportunity cost of domestic oil and gas consumption, which is reflected in international price of hydrocarbon resources. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2016), generating 1 MWh of electricity requires 1.73 barrels of oil or 10.11 mcf of natural gas. The record low auction prices for solar photovoltaics (PV) in Dubai, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia have shown that, under the right circumstances, an LCOE (levelised cost of electricity) of $0.03/kWh for solar is achievable. IRENA also estimates the global average cost of solar PV to be around $0.06/kWh. If the lower band is considered (which is closer to costs of solar at the region), the break-even prices of oil and gas would be $17.34/bbl and $2.96/mcf, respectively, which are well below international prices. If we consider the global average costs of solar instead (which is pretty much conservative for the region), the break-even prices will increase to $34.68/bbl and $5.93/mcf, which is still below the international price for oil but slightly higher than the average price for natural gas. Even if we add the costs of dealing with solar intermittency (at around $5/MWh) to these numbers, the economics of renewables is still winning over traditional resources in these countries. The economics of renewables will be boosted if we account for the gain that these countries will make from liberated oil and gas for exports. This highlights the importance of integrating renewable into the existing fossil fuel-based generation mix of oil-exporting countries (Fattouh et al. 2018, 20).

References

BP (2018) Annual Energy Outlook. https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/en/corporate/pdf/energy-economics/energy-outlook/bp-energy-outlook-2018.pdf [Accessed January 30, 2019].

Curtis, T. and Montalbano, B. (2017) ‘Completion Design Changes and the Impact on US Shale Well Productivity’, Energy Insight 21, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Dale, S. and Fattouh, B. (2018) ‘Peak Oil Demand and Long Run Oil Prices’, OIES Energy Insight 25, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/peak-oil-demand-long-run-oil-prices/. [Accessed January 30, 2019]

EIA (2017) International Energy Outlook, US Energy Information Administration.

EIA (2018) International Energy Outlook, US Energy Information Administration.

Fattouh, B., Poudineh, R. and West, R. (2018) ‘The Rise of Renewables and Energy Transition: what adaptation strategy for oil companies and oil-exporting countries?’, OIES Paper MEP19, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/rise-renewables-energy-transition-adaptation-strategy-oil-companies-oil-exporting-countries/ [Accessed January 30, 2019].

Fattouh, B. and Shehabi, M. (2019) The Gulf Economies’ Long Road towards Better Diversification, WE Energy.

FT (2018) ‘BP Says Oil Demand to Peak by Late 2030s’, Financial Times, February 20.

Fulton, L, Mason, J., and Meroux, D. (2017) ‘Three Revolutions in Urban Transportation’, UC Davis Sustainable Transportation Energy Pathways of the Institute of Transportation Studies. https://www.itdp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/UCD-ITDP-3R-Report-FINAL.pdf [Accessed January 30, 2019].

Sovacool, B.K. and Geels, F.W. (2016). ‘Further reflections on the temporality of energy transitions: A response to critics’, Energy Research & Social Science, 22, 232–7.

IEA (2017) World Energy Outlook, International Energy Agency, Paris.

IEA (2018a) ‘Oil 2018: Analysis and Forecasts to 2023’, International Energy Agency, Paris.

IEA (2018b) ‘Outlook for Producer Economies: What do changing energy dynamics mean for major oil and gas exporters?’ International Energy Agency, Paris.

IEA (2018c) World Energy Outlook, International Energy Agency, Paris.

IMF (2016) ‘Economic Diversification in Arab Oil Exporting Countries’, Annual Meeting of Arab Ministers of Finance, April 2016, International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2016/042916.pdf [Accessed January 30, 2019].

IRENA (2019) ‘Renewable Energy Market Analysis—GCC 2019’, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. https://irena.org/publications/2019/Jan/Renewable-Energy-Market-Analysis-GCC-2019 [Accessed January 30, 2019].

Luciani, G. (2019) ‘Unsustainable, but why?’, Oxford Energy Forum, March, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Matar, W., Murphy, F., Pierru, A., Rioux, B. and Wogan, D. (2017) ‘Efficient industrial energy use: the first step in transitioning Saudi Arabia’s energy mix’, Energy Policy, 105, pp. 80-92.

OPEC (2017) World Oil Outlook, Organisation of Oil Exporting Countries.

Poudineh, R., Sen, A. and Fattouh, B. (2016) ‘Advancing Renewable Energy in Resource-Rich Economies of the MENA’, OIES Paper MEP15, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/rise-renewables-energy-transition-adaptation-strategy-oil-companies-oil-exporting-countries/ [Accessed January 30, 2019].

Shehabi, M. (2019) ‘GCC economies do not need diversification; they need better diversification’, Oxford Energy Forum, March, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fattouh, B., Sen, A. (2021). Economic Diversification in Arab Oil-Exporting Countries in the Context of Peak Oil and the Energy Transition. In: Luciani, G., Moerenhout, T. (eds) When Can Oil Economies Be Deemed Sustainable?. The Political Economy of the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5728-6_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5728-6_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-5727-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-5728-6

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)