Abstract

The institutional arrangements governing the creation of new money in the United States have changed dramatically since the Revolution. Yet beneath the surface the story of wartime money creation has remained much the same. During wars against minor powers, the government was able to fund the war by borrowing and levying taxes. During wars against major powers, however, the story was very different. In major wars there came a point when further increases in taxes could not be undertaken for administrative or political reasons, and further increases in borrowing could not be undertaken except at higher interest rates, rates that exceeded what was considered fair based on prewar norms. At those moments governments turned to the printing press. The result was substantial inflation.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

The one partial exception is the Vietnam War. The war, as discussed below, did contribute to the excessive monetary growth that characterized the late 1960s and early 1970s. But there were other factors besides the war.

- 2.

By perpetually funding Smith meant issuing consols. Since the bonds would never mature, taxes only had to be raised sufficiently to pay the interest on the bonds.

- 3.

More formally, money creation can be regarded as part tax and part borrowing by the government at zero interest. Start with a quantity equation (1) M = kPy where M is the stock of money, k is the proportion of income held as money, P is the price level, and y is real income. Differentiating both sides and rearranging terms produces (2) \( \Delta \mathrm{M}/\mathrm{P}=\left(\mathrm{M}/\mathrm{P}\right)\left(\Delta \mathrm{P}/\mathrm{P}\right)+\left(\mathrm{M}/\mathrm{P}\right)\left(\Delta \mathrm{k}/\mathrm{k}+\Delta \mathrm{y}/\mathrm{y}\right) \). The term on the left-hand side is the government’s revenues from inflation. The first term on the right is the inflation tax: the product of the rate of inflation (the tax rate) and the real stock of money (the tax base). The second term on the left is the amount of money the economy will absorb before inflation sets in because more is demanded for transactions or precautionary purposes.

- 4.

The discussion here abstracts from the decision about the amount of resources to devote to the war effort. In reality, however, that decision will also be part of the balancing act. The war government may decide that cutting the amount of resources devoted to the war is less costly than increasing one of the means of finance.

- 5.

See Calomiris (1988) for a related but somewhat different interpretation of the Continental dollar.

- 6.

Hence, the Constitution uses the now mysterious term “bill of credit, rather than paper money or cash.”

- 7.

Alternatively, one could think of the depreciation of the Continental dollar in specie as an increase in the Continental dollar price level.

- 8.

Cagan, however, added that the 50 % rate had to persist for a year.

- 9.

The island of Manhattan is 13,000 acres.

- 10.

The interest rate on these notes was set, typically, at 7.3 %. This works out to be 2 cents per day on $100, facilitating circulation from hand to hand.

- 11.

Presciently, Adam Smith warned in The Wealth of Nations about the dangers of depending on bank notes because of the risk of an enemy capturing the nation’s capital.

- 12.

Using the calculator at www.measuringworth.com

- 13.

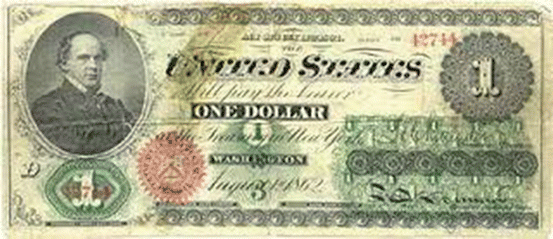

They were known as greenbacks, of course, for their color which became traditional for American currency, and perhaps also because they were “backed” by green ink rather than by gold.

- 14.

Except for tariffs, which had to be paid in specie. Allowing tariffs to be paid in greenbacks would in effect have lowered the tariff rate, something anathema to the Republicans.

- 15.

The inflation was more severe in the South, which relied more heavily on the printing press.

- 16.

But western farmers, another important constituent of the party, one imagines, were debtors.

- 17.

Using the unskilled wage as the inflator. Using a price index would yield a lower figure of about $35,000,000. Data from www.measuringworth.com

- 18.

Kang and Rockoff (2006) discuss in some detail the efforts to market the bonds.

- 19.

This paragraph is based mainly on Friedman and Schwartz (1963, 221–231).

- 20.

Eccles was appointed by Roosevelt and generally supported the Keynesian (perhaps more accurately proto-Keynesian) view that the main function of monetary policy in most circumstances was to keep interest rates low.

- 21.

Although they did not modify their estimates of the stock of money to include government debt during the period when bond prices were fixed by the Federal Reserve.

- 22.

The Constitution grants the federal government the right to coin money (presumably gold and silver) and to issue notes (interest-bearing securities). It is silent on federal bills of credit (paper money).

- 23.

Bank et al. (2008, 136) describe the details of the tax. 10 % was an exaggeration because it applied for only part of the tax year.

- 24.

Meltzer (2009, volume 2, book 1, 441–79 is a detailed account of Federal Reserve policy in the mid-1960s.

References

Bank, Steven A., Kirk J. Stark, and Joseph J. Thorndike. 2008. War and taxes. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Barro, Robert J. 1987. Government spending, interest rates, prices and budget deficits in the United Kingdom, 1701–1918. Journal of Monetary Economics 20: 195–220.

Barro, Robert J. 1989. The neoclassical approach to fiscal policy. In Modern business cycle theory, ed. Robert J. Barro. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bockstruck, Lloyd DeWitt. 1996. Revolutionary war bounty land grants: Awarded by state governments. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co.

Cagan, Phillip. 1956. The monetary dynamics of hyperinflation. In Studies in the quantity theory of money, ed. Milton Friedman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Calomiris, Charles W. 1988. Institutional failure, monetary scarcity, and the depreciation of the continental. The Journal of Economic History 48(1): 47–68. March.

Dewey, Davis Rich. 1931. Financial history of the United States. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Flexner, James Thomas. 1984. Washington: The indispensable man. Boston: Little Brown.

Friedman, Milton. 1952. Price, income, and monetary changes in three wartime periods. The American Economic Review 42(2), Papers and Proceedings of the Sixty-fourth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association) (May): 612–625.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz. 1963. A monetary history of the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz. 1970. Monetary statistics of the United States. New York: Columbia University Press.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz (eds.). 1982. Monetary trends in the united states and the united kingdom: Their relation to income, prices, and interest rates, 1867–1975. National bureau of economic research monograph. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gates, Paul Wallace. 1968. History of public land law development. Washington: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

Grubb, Farley. 2008. The continental dollar: How much was really issued? The Journal of Economic History 68(1): 283–291.

Grubb, Farley. 2011a. The distribution of congressional spending during the American Revolution, 1775–1780: The problem of geographic balance. In The spending of States. Military expenditure during the long eighteenth century: Patterns, organization, and consequences, 1650–1815, ed. Stephen Conway and Rafael Torres Sãnchez, 257–284. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr Müller.

Grubb, Farley. 2011b. The continental dollar: Initial design, ideal performance, and the credibility of congressional commitment. NBER Working Paper No. 17276, Issued in August.

Hibbard, Benjamin Horace. 1965 [1924]. A history of the public land policies. Madison and Milwaukee: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Hickey, Donald R. 1989. The war of 1812: A forgotten conflict. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Historical Statistics of the United States Millennial Edition Online. 2006. Retrieved from http://hsus.cambridge.org/.

Kang, Sung Won, and Hugh Rockoff. 2006. Capitalizing patriotism: The liberty loans of World War I. NBER Working Paper 11919.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1920 [1919]. The economic consequences of the peace. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe.

McCusker, John J. 2001. How much is that in real money? A historical commodity price index for use as a deflator of money values in the economy of the United States, 2nd ed. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

Meltzer, Allan H. 2003, 2009. A history of the federal reserve. Two volumes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mill, John Stuart, and W. J. Ashley. 1936 [1848]. Principles of political economy, with some of their applications to social philosophy. London/New York: Longmans, Green.

Ratchford, Benjamin Ulysses. 1941. American state debts. Duke University Publications. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rockoff, Hugh. 2012. America’s economic way of war: War and the US economy from the Spanish-American War to the Persian Gulf War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Adam. 1976 [1776]. An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. The Glasgow edition of the works and correspondence of Adam Smith., ed. R.

Truman, Harry S. 1955, 1956. Memoirs. 1st ed. Garden City: Doubleday.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1: The Means of Finance for America’s Wars

Revolution | War of 1812 | Mexican War | Civil War (North) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Start | April 1775 | June 1812 | May 1846 | April 1861 |

End | September 1783 | December 1814 | February 1848 | April 1865 |

Means of finance | 1. Printing money | 1. Borrowing from the public | 1. Borrowing from the public | 1. Borrowing from the Public |

2. Borrowing from the public | 2. Printing money | 2. Land grants | 2. Taxes | |

3. Borrowing from foreign countries | 3. Taxes | 3. Printing money | ||

4. Land grants | 4. Land grants | 4. Conscription | ||

5. Conscription | 5. Letters of marque | |||

6. Letters of marque | ||||

Spanish-American and Philippine-American War | World War I | World War II | Korean War | |

Start | April 1898 | April 1917 | December 1941 | June 1950 |

End | July 1902 | November 1918 | September 1945 | June 1953 |

Means of finance | 1. Taxes | 1. Borrowing from the public | 1. Taxes | 1. Taxes |

2. Borrowing from the public | 2. Printing money | 2. Borrowing from the public | 2. Conscription | |

3. Printing money | 3. Taxes | 3. Printing money | ||

4. Conscription | 4. Conscription | |||

Vietnam War | Persian Gulf War | |||

Start | August 1964 | January 1990 | ||

End | April 1973 | March 1990 | ||

Means of finance | 1. Borrowing from the public | 1. Contributions of foreign governments | ||

2. Taxes | ||||

3. Printing Money |

Appendix 2: A Catalog of Some of the Currency That Helped Finance America’s Wars

-

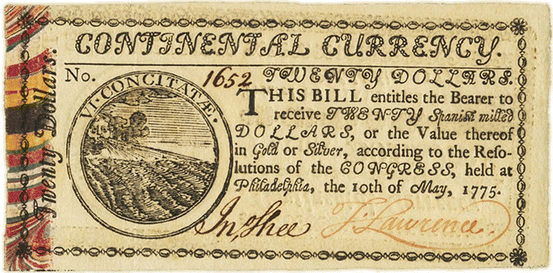

1.

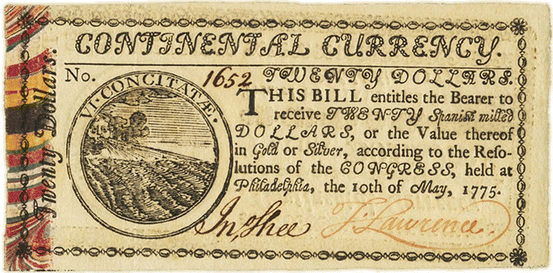

A Continental note for 20 dollars issued according to the May 1775 resolution of Congress. The resolution promised redemption in 3 Spanish milled Dollars (pesos) between 1779 and 1782. Redemption would be carried out by the states, which would also make the notes legal tenders.

-

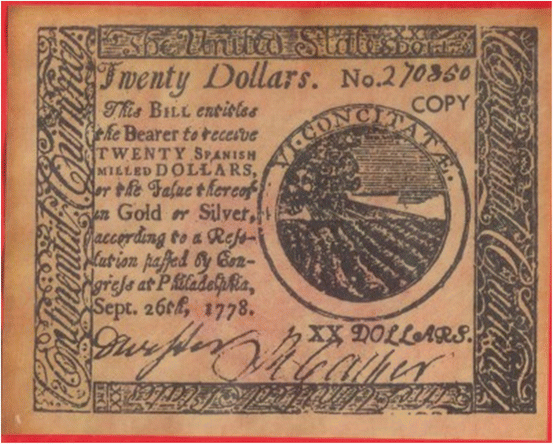

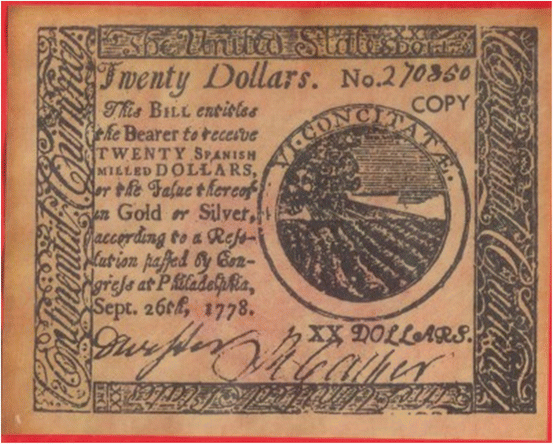

2.

A Continental note for 20 dollars issued according to a resolution of September 1778. The note promised redemption (according to Farley Grubb’s 2011b, 15, calculations) between 1815 and 1817.

-

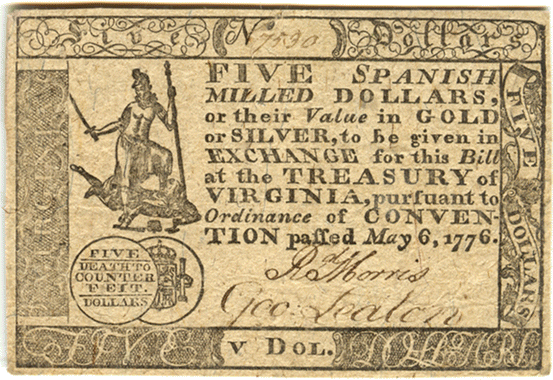

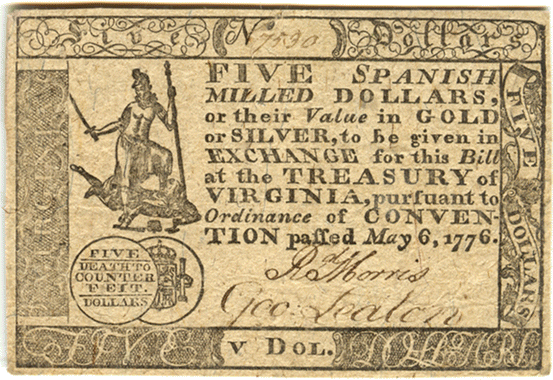

3.

A note issued by Virginia in 1776. The presence of state-issued notes and counterfeits – despite the death threat – make it difficult to compute the stock of money during the Revolution.

-

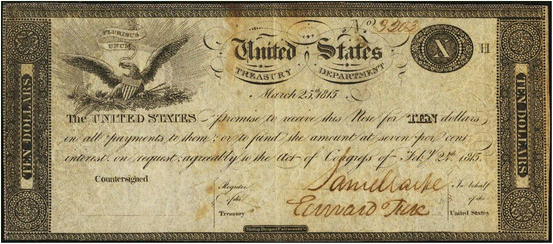

4.

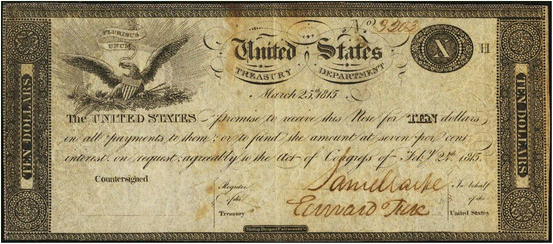

Ten-dollar interest-bearing Treasury Note from the War of 1812

-

5.

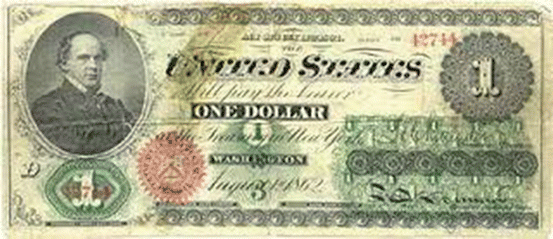

A Civil War greenback.

-

6.

A National Bank note issued by the First National Bank of Newark. It was secured by bonds of the United States.

-

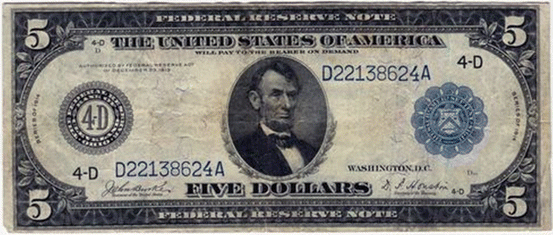

7.

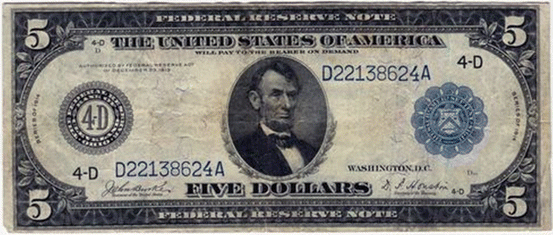

A Federal Reserve Note from 1914.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Editors

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rockoff, H. (2016). War and Inflation in the United States from the Revolution to the Persian Gulf War. In: Eloranta, J., Golson, E., Markevich, A., Wolf, N. (eds) Economic History of Warfare and State Formation. Studies in Economic History. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1605-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1605-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-1604-2

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-1605-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)