Abstract

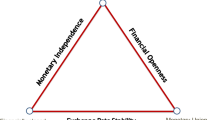

We develop a new set of indexes of exchange rate stability, monetary policy independence, and financial market openness as the metrics for the trilemma hypothesis. In our exploration, we take a different and more nuanced approach than the previous indexes developed by Aizenman et al. We show that the new indexes add up to the value two, supporting the trilemma hypothesis. We locate our sample economies’ policy mixes in the famous trilemma triangle—a useful and intuitive way to illustrate the state and evolution of policy mixes. We also examine if the persistent deviation of the sum of the three indexes from the value two indicates an unsustainable policy mix and therefore needs to be corrected by economic disruptions such as economic and financial crises. We obtain several findings. First, such a persistent deviation can occur particularly in emerging economies that later experience an inflation (or potentially a general or a currency) crisis, and dissipates in the postcrisis period. Second, there is no evidence for this type of association between deviations from the trilemma constraint and general, banking, or debt crises. Third, Thailand experienced such a deviation from the trilemma constraint in the period leading to the baht crisis of 1997, but not other East and Southeast Asian economies. This last result suggests that the main cause for the Thai baht crisis was an unsustainable policy mix in the precrisis period, while other affected economies experienced crises mainly due to contagion from Thailand.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Exchange rate rigidities could make policymakers blind in reading appropriate market signals and therefore may make their economies prone to asset boom and bust cycles.

- 2.

The base country is defined as the country that a home country’s monetary policy is most closely linked with as in Shambaugh (2004); it is either Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, India, Malaysia, South Africa, the United Kingdom, or the US. More details on the construction of the indexes can be found in Aizenman et al. (2008).

- 3.

Quinn et al. (2010) reviews a variety of indexes that measure the extent of financial market openness or capital controls.

- 4.

The working paper version of this chapter (Ito and Kawai 2012) reports the data availability and lists the economies for which the indexes are available.

- 5.

One may also consider imposing the constraint of \( {{\displaystyle {\sum}_{k=1 k}^{K{\prime}}\widehat{\beta}}}_k=1 \) in the estimation. However, we decided not to do so. We would rather keep the estimation model as a general form because some currencies in our sample may have adopted fully flexible exchange rates which can be precluded by having the above constraint.

- 6.

When all of the right-hand side variables turn out to be statistically insignificant (with all the p-values greater than 20 %), the currency that has the lowest p-value is retained in the estimation.

- 7.

- 8.

Even when the monetary authorities of a country adopt a floating exchange rate system, it is often the case that they usually have a target currency (which is the same as the “base country” in the context of Shambaugh 2004 and Aizenman et al. 2008) in mind whose movement can affect the country’s exchange rate. This target currency must be the currency that has the lowest p-value even if all the currencies on the right-hand side of the estimation are found statistically insignificant.

- 9.

Since Bhutan and Sri Lanka peg their currencies to the Indian rupee, the Indian rupee is also included in the estimation for these countries. For the same reason, the estimations equations for the currencies of Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, and Swaziland include the South African rand as one of the right-hand side currencies. For several countries in the Pacific, the Australian dollar is included.

The estimation also includes a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the monthly rate of change in the exchange rate of the sample currency is greater than 10 % in absolute terms so as to minimize noise from exchange rate disruptions such as abortion of an exchange rate regime and sudden re/devaluation of the currency. Similarly, we include a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 in the first month after the introduction of the euro.

- 10.

Following the Frankel and Wei estimation for the exchange rate, only significant estimates (or the estimate that has the lowest p-value) are included.

- 11.

That is, if home country i closely follows the monetary policy of the countries included in the basket, the goodness of fit of Eq. (4.2) must be high (while γ it should be close to the value of one), which means the home country’s monetary policy is dependent on the (weighted average) monetary policy of the basket countries.

- 12.

Given the Fisher equation, the stationarity of the nominal interest rate series is conditional upon the stationarity of the expected rate of inflation series or that of the real interest rate series. Theoretically, it is difficult to argue the non-stationarity of the real interest rate, although the real interest rate series can involve structural breaks, causing non-stationarity in a statistical test (Huizinga and Mishkin 1984; Garcia and Perron 1996). Given the past episodes of hyperinflation in many countries, the rate of inflation series can be non-stationary, as has been shown in many studies.

- 13.

We use the change in the policy rates over 12 months instead of month-to-month changes, that is, first-differences, because of the following reasons. First, estimation with the first-differenced policy rates would involve too much noise that affects both the estimated coefficients and adjusted R2. Second and more importantly, estimating Eq. (4.2) in first-difference form is essentially the same as assuming that the home country must react to a change in the foreign interest rate i* within 1 month, which may be too restrictive an assumption.

- 14.

We do not necessarily assume all the countries in our sample follow the Taylor rule, as the domestic variables can be insignificant contributors to the decision making of the policy rate in some countries.

- 15.

More specifically, we include the interest rate dummy that takes the value of one if the policy interest rate is greater than 100 %; the inflation dummy that takes the value of one if the change in the rate of inflation from the same month in the previous year is greater than 50 %; and the interest rate change dummy that takes the value of one if the change in the policy rate is greater than 5 % points from the previous month or 50 % points from the same month in the previous year. The currency crisis dummy takes the value of one when the EMP index exceeds the threshold of mean plus or minus 2 standard deviations of the index.

The EMP index is constructed as the weighted average of monthly changes in the nominal exchange rate, the nominal interest rate, and foreign exchange reserves in percentage. The exchange rate is between the home currency and the currency of the base country (as defined in Shambaugh 2004). The changes in the nominal interest rate and foreign exchange reserves are included as the differentials from those of the “base country.” For the countries whose base countries are not defined by Shambaugh (2004), we follow the definition made by Aizenman et al. (2008). The weights are inversely related to the variance of changes in each component for each of the sample countries. When we calculate the standard deviations of the EMP index for the threshold, we exclude the EMP values that are lower than the bottom one percentile or greater than the top one percentile because outliers of the EMP index can make the standard deviations unnecessarily large and thereby make the thresholds too unreliable for some countries, especially those which have experienced significant swings in their EMP indexes.

- 16.

A more straightforward way of measuring the extent of monetary policy dependence would be to use \( \widehat{\gamma} \) in Eq. (4.4). However, \( \widehat{\gamma} \) is found to be quite unstable (despite inclusion of the dummies). For some developing countries that have experienced episodes of high inflation, the estimated \( \widehat{\gamma} \) can easily surpass the value of 1.

- 17.

Specifically, we use the following rule: If the adjusted R2 of Eq. (4.5) is greater than the sum of the adjusted R2 of Eq. (4.6) and the standard error of the difference between the two adjusted R2’s, then we take MI_1 as the MI index. If the adjusted R2 of Eq. (4.6) is greater than the sum of the adjusted R2 of Eq. (4.5) and the standard error of the difference between the two adjusted R2’s, then we take MI_2 as the MI index. If the difference between the two adjusted R2’s is within its standard error, then we use the average of the two MI indexes.

- 18.

We exclude Luxembourg from the calculation since it is an extreme outlier due to its role of an international financial center. The de jure index of financial openness developed by Chinn and Ito (2006, 2008) also shows that the level of financial openness reached the highest level in the mid-1990s and has plateaued since then.

- 19.

Any FO i * taking a value above one is assumed to be one.

- 20.

We also update the data on external assets and liabilities using the international investment positions data of the IMF’s International Financial Statistics.

- 21.

Appendix 2 of the working paper version of this chapter (Ito and Kawai 2012) further explains the linearity of the three indexes and why they must add up to 2.

- 22.

“High-,” “middle-,” and “low-income” economy groups are based on the World Bank’s classifications. ”High income economies” include Australia; Austria; Bahrain; Barbados; Belgium; Canada; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Hong Kong, China; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Japan; Kuwait; Luxembourg; Malta; Netherlands; New Zealand; Norway; Oman; Poland; Portugal; Qatar; Saudi Arabia; Singapore; Slovak Republic; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Trinidad & Tobago; and United Kingdom. “Emerging economies” refer to the economies included in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. They are Argentina; Brazil; Chile; People’s Republic of China; Colombia; Czech Republic; Egypt; Hungary; India; Indonesia; Israel; Jordan; Republic of Korea; Malaysia; Mexico; Morocco; Pakistan; Peru; Philippines; Poland; Russian Federation; South Africa; Taipei,China; Thailand; Turkey; and Venezuela.

- 23.

Emerging Asian economies include the PRC, Indonesia, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand.

- 24.

The adjustment is further explained in Appendix 2-2 of the working paper version of this chapter (Ito and Kawai 2012).

- 25.

This identification is the same as “excessively severe recession” in Aizenman et al. (2012). The standard deviation is based on rolling 5-year windows. The long-run average of per capita income growth is the average of the growth in the 1950–2009 period. The per capita income data are retrieved from Penn World Table 7.0.

- 26.

It is also supplemented by the currency crisis identification by Reinhart and Rogoff (2009).

- 27.

However the sum of the three indexes for emerging economies is significantly greater than the subsample mean in the crisis year (t), with the statistical significance of 80 %. Here the subsample mean of the sum of the three indexes is calculated for both crisis and non-crisis emerging economies over the entire period. So as far as a currency crisis in concerned, there is some, though weak, evidence that there may have been such a deviation if a benchmark is the sample mean, rather than the value two.

- 28.

- 29.

We identify an inflation crisis if there are more than 5 months in a year when the annual growth rate of consumer price index (CPI) is over 20 %. This definition draws from Reinhart and Rogoff (2009).

- 30.

In addition, there is some evidence that the sum of the three indexes exceeds the subsample mean for crisis and non-crisis emerging economies over the entire period.

References

Aizenman, J., Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2008). Assessing the emerging global financial architecture: Measuring the trilemma’s configurations over time (National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 14533).

Aizenman, J., Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2012). The financial crisis, rethinking of the global financial architecture, and the trilemma. In M. Kawai, P. Morgan, & S. Takagi (Eds.), Monetary and currency policy issues for Asia: Implications of the global financial crisis (pp. 143–206). Cheltenham/Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Aizenman, J., Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2013). The ‘impossible trinity’ hypothesis in an era of global imbalances: Measurement and testing. Review of International Economics, 21(23), 447–458.

Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2006). What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 163–192.

Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2008). A new measure of financial openness. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 10(3), 309–322.

Eichengreen, B., Rose, A., & Wyplosz, C. (1995). Exchange market mayhem: The antecedents and aftermaths of speculative attacks. Economic Policy, 21, 249–312.

Eichengreen, B., Rose, A., & Wyplosz, C. (1996). Contagious currency crises: First tests. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 98(4), 463–484.

Frankel, J., & Wei, S. J. (1994). Yen bloc or dollar bloc? Exchange rate policies: The East Asian economies. In T. Ito & A. Krueger (Eds.), Macroeconomic linkage: Savings, exchange rates, and capital flows (pp. 295–333). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Garcia, R., & Perron, P. (1996). An analysis of the real interest rate under regime shifts. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78, 111–125.

Huizinga, J., & Mishkin, F. (1984). Inflation and real interest rates on assets with different risk characteristics. Journal of Finance, 39(3), 699–712.

Ito, H., & Kawai, M. (2012). New measures of the trilemma hypothesis: Implications for Asia (ADBI Working Paper Series No. 381). Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Kawai, M., & Akiyama, S. (1998). The role of nominal anchor currencies in exchange rate arrangements. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 12, 334–387.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2010). Resolution of banking crises: The good, the bad, and the ugly (IMF Working Paper 10/146). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Lane, P., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2001). The external wealth of nations: Measures of foreign assets and liabilities for industrial and developing countries. Journal of International Economics, 55, 263–294.

Lane, P., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2007). The external wealth of nations mark II: Revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970–2004. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 223–250.

Mundell, R. A. (1963). Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rates. Canadian Journal of Economic and Political Science, 29(4), 475–85.

Obstfeld, M., Shambaugh, J. C., & Taylor, A. M. (2005). The trilemma in history: Tradeoffs among exchange rates, monetary policies, and capital mobility. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(August), 423–438.

Quinn, D., Schindler, M., & Toyoda, A. M. (2010). Assessing measures of financial openness and integration. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Unpublished.

Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. (2009). This time is different: Eight centuries of financial folly. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shambaugh, J. C. (2004). The effects of fixed exchange rates on monetary policy. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 301–352.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ito, H., Kawai, M. (2014). New Measures of the Trilemma Hypothesis: Implications for Asia. In: Kawai, M., Lamberte, M., Morgan, P. (eds) Reform of the International Monetary System. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55034-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55034-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Tokyo

Print ISBN: 978-4-431-55033-4

Online ISBN: 978-4-431-55034-1

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)