Abstract

This chapter examines the extent to which people in the second half of life felt threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic, whether there were differences between middle-aged and older individuals, and the role of self-rated health. This chapter also addresses how people perceived their influence on contracting COVID-19.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Key Messages

The majority of individuals in the second half of life did not perceive the Covid-19 risis as very threatening. About 9 per cent of individuals in the second half of life (46 to 90 years) felt very threatened by the Covid-19 crisis, 42 per cent indicated a medium level of threat and about 50 per cent rated the threat as low.

Self-rated health played an important role in the perceived threat of the Covid-19 crisis. Individuals who rated their health as less good felt significantly more threatened by the pandemic than individuals who rated their health as very good or good. In addition, individuals with a lower educational level felt more threatened than people with a higher educational level. In contrast, age, gender and Covid-19 infections in an individual’s personal environment did not play a significant role in threat perception.

The majority felt that they could influence the risk of contracting Covid-19 at least to a moderate extent. 23 per cent rated their influence on a possible infection as high, 65 per cent as medium and 12 per cent as low.

Self-rated health also played an important role in subjective influence on contracting Covid-19. People who rated their health as less good reported having a lower subjective influence on contracting Covid-19 than people with good self-rated health. Education and age were also important: people between 61 and 75 and people with a high educational level perceived a greater subjective influence. Gender and the presence of people who had Covid-19 in respondents’ personal environments did not play an important role for subjective influence.

Perceived threat from the Covid-19 crisis and subjective influence on contracting Covid-19 were only weakly associated with each other. The groups of those who felt a high threat and of those who believed they only had little influence the risk of contracting Covid-19 were not congruent. Among those who felt more threatened by the Covid-19 crisis, the proportion of people who were convinced that they could influence the risk of infection was greater than among people with a low threat perception. At the same time, however, a greater proportion of people in this group also believed that they had little influence ompared to people with a low threat perception.

People who perceived a high threat and those who perceived low subjective influence had lower well-being. People who felt more threatened by the Covid-19 crisis and people who perceived little influence over contracting Covid-19 were less satisfied with their lives and reported more depressive symptoms than people with lower threat perceptions and higher subjective influence.

2 Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic is an ongoing global crisis that poses a considerable threat to health and quality of life across the world, to the global economy as well as to social coexistence and interaction. Although Germany has so far been less affected by Covid-19 infections and deaths than many other countries in Europe (Stafford 2020), the Covid-19 crisis has nevertheless profoundly changed the everyday lives of many individuals in Germany as well. This is not only due to the threat posed by Covid-19 but also to the far-reaching measures taken to contain the virus (e.g., physical distancing, hygiene measures, use of everyday masks) or travel and contact restrictions and even bans on visits to care facilities and hospitals. In addition, numerous cultural events were cancelled and institutions such as schools, and day-care centres were temporarily closed.

These measures were successful in Germany: infection rates and mortality rates remained comparatively low during the first Covid-19 wave. At the same time, however, these restrictive measures had and still have a considerable impact on the organisation of everyday life. This concerns, for example, the maintenance of personal social relationships, which had to be reduced or changed from face-to-face meetings to contacts via phone or internet. Many people also had to reorganise their daily work and family life, for example, by working from home and reorganising the care of their children and grandchildren as long as childcare facilities were closed. Leisure time activities also changed for many people: for example, opportunities for playing sports were limited at times, as sports facilities remained closed. Some people were also significantly affected financially by the Covid-19 pandemic because of income loss, for example, because they were furloughed, became unemployed or even faced the bankruptcy of their own company.

For people in the second half of life, the Covid-19 pandemic has posed a particular challenge and threat: The probability of experiencing severe Covid-19 or dying from the disease when infected increases significantly with age (Robert Koch Institute 2020). What does this mean for these people’s subjective perspectives on the pandemic, or, to put it another way, how did people in the second half of life experience the threat of Covid-19? And were there differences between population subgroups—for example, according to gender, education, self-rated health or Covid-19 infections in an individual’s personal environment?

A similar question can be asked with regard to individuals’ subjective influence on the risk of contracting Covid-19. Did people in the second half of life believe they had an influence on whether they contracted Covid-19? And were there also differences according to age, gender, education, self-rated health or Covid-19 infections in an individual’s personal environment?

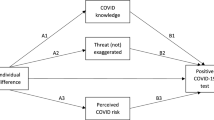

Of importance for prevention measures is the question of whether and how the experience of threat from the Covid-19 crisis and subjective influence on the risk of infection were connected. Was subjective influence high when the threat was perceived as high? In this case, the threat experience may have led people to exercise increased caution in everyday life to maximise their influence on a possible infection. Or was subjective influence particularly high when the threat was perceived as low? It is possible that people perceived the threat of the Covid-19 crisis as low when they thought they had a considerable influence on contracting the disease. Conversely, high threat perception could have led to fatalism and an attitude that individuals can exert only little or no influence on the risk of contracting Covid-19. Media and political risk communication would need to be framed differently depending on how people perceived the threat of Covid-19 and their subjective influence on it and depending on the size and direction of the connection between the two types of perception (threat and influence).

Finally, the perception of the Covid-19 crisis might also have been relevant for the subjective well-being of people in the second half of life. Did people who perceived a high threat from the Covid-19 crisis and little influence over their risk of contracting it experience lower subjective well-being? People who felt highly threatened, as well as people who saw little possibility to protect themselves from Covid-19, may have been less satisfied with their lives and more depressed during the first COVID-19 wave in Germany than people with a more optimistic perspective on Covid-19.

Research questions

This chapter examines the following four questions:

-

Perceived threat from the Covid-19 crisis

To what extent did people in the second half of life feel threatened by the Covid-19 crisis? Did different population groups feel differently threatened? The characteristics of age, gender, education, self-rated health and Covid-19 cases in an individual’s personal environment were considered.

-

Subjective influence on the risk of contracting Covid-19

To what extent did people in the second half of life feel they could influence a possible infection with Covid-19? Were there differences between different population groups? Again, age, gender, education, self-rated health and Covid-19 cases in an individual’s personal environment were considered.

-

Relationship between the perceived threat of the Covid-19 crisis and subjective influence on one’s Covid-19 infection risk

How was the perceived threat of Covid-19 related to perceptions of subjective influence on the risk of contracting Covid-19? Were people more likely to feel that they could influence the possibility of contracting Covid-19 when they experienced a low or a high threat from the pandemic? Or were perceived threat and subjective influence relatively independent of each other?

-

Perception of the Covid-19 crisis and subjective well-being

Were people less satisfied with their lives and more likely to be depressed if they felt more threatened by the Covid-19 crisis and if they believed they could hardly influence their likelihood of contracting Covid-19?

3 Data and Methods

The results of this chapter are based on analyses of the seventh wave of the German Ageing Survey (DEAS; Vogel et al. 2020). For the present analysis, the data of 4762 persons aged between 46 and 90 years were used.

The following measures were included for the analyses:

-

The perceived threat of the Covid-19 crisis was captured by the question: “Please indicate to what extent you currently perceive the Covid-19 crisis as a threat for yourself.”Footnote 1 Respondents answered this question by giving a number between 1 (no threat to me at all) and 10 (extreme threat to me).

-

The subjective influence on a possible infection with Covid-19 was assessed with the question: “To what extent do you feel that you can influence an infection with the coronavirus yourself?”Footnote 2 This question was answered by the respondents on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (entirely).

-

In order to assess Covid-19 infections in the respondent’s own environment, the following question was asked: “Have people from your personal environment been infected with the coronavirus?”Footnote 3 The possible answers to this question were “Yes”, “No” or “Don’t know”.Footnote 4

-

The question “How would you rate your urrent state of health?” was used to assess self-rated health. The question was answered on a scale from 1 (very good) to 5 (very poor). In the following analyses, scores of 1 and 2 are interpreted as “very good/good self-rated health” and scores from 3 to 5 as “moderate to poor self-rated health”.

-

Subjective well-being was assessed via two indicators, life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Life satisfaction was measured via the German version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985). This scale consists of five statements (e.g. “I am satisfied with my life”), which were answered on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). A mean score was calculated across the five statements and transformed so that higher values indicated higher life satisfaction. Values above 3.3 were interpreted as high life satisfaction (Wolff and Tesch-Römer 2017). Depressive symptoms were assessed using a short version of the CES-D Depression Scale (Radloff 1977). This short version consisted of ten statements (e.g. “During the last week I felt exhausted”), each of which was answered on a scale from 1 (rarely) to 4 (always). For each person, a sum score was calculated across all statements (for this computation, the score range of the items was transformed from 1–4 to 0–3). Values above the scale mean of 15 were interpreted as indicating pronounced depressive symptoms.

Age, gender and education were determined based on self-reporting or were already known due to previous participation in the German Ageing Survey. In order to examine the role of age, three age groups were created: 46–60-year-olds (n = 996; 20.9 per cent), 61–75-year-olds (n = 2166; 45.5 per cent) and 76–90-year-olds (n = 1600; 33.6 per cent). In addition, women (n = 2434; 51.1 per cent) and men (n = 2328; 48.9 per cent) were compared. Education was divided into three groups according to the ISCED classification: persons with a low educational level (n = 205; 4.3 per cent), a medium educational level (n = 2250; 47.3 per cent) and a high educational level (n = 2306; 48.4 per cent).

4 Perceived Threat from the Covid-19 Crisis

Most individuals in the second half of life did not perceive the Covid-19 crisis as a strong threat

Respondents’ answers to the question of whether they experienced the Covid-19 crisis as a threat to themselves were distributed very unevenly across the ten response options (Fig. 4.1): The proportion of people who perceived the Covid-19 crisis as a rather low threat was considerably larger than the proportion of people who perceived the Covid-19 crisis as a high threat. The most frequent scores were 3 (23.5 per cent) and 5 (16.9 per cent). The values of 9 and 10, which reflect an extremely high threat experience, were selected by less than 4 per cent of the sample.

When we divided the values into three groups (Fig. 4.1), we found that less than half of the respondents (48.5 per cent) selected values between 1 and 3 (low perceived threat from the Covid-19 crisis). Values between 4 and 7, reflecting a medium threat experience, were selected by 42.3 per cent of respondents. And finally, less than one in ten (9.2 per cent) selected values above 7 and thus indicated a sense of high personal threat.

When we compared these three groups—which perceived the Covid-19 crisis as either not very threatening, moderately threatening or very threatening—according to various characteristics (age, gender, education, Covid-19 in the personal environment; Fig. 4.2), the following picture emerges: in the oldest group (76 years and older), the proportion of those who felt slightly threatened was a bit smaller (46.3 per cent) than among those aged 46 to 60 (49.4 per cent) and those aged 61 to 75 (48.4 per cent). However, the oldest group had a lower proportion of people who felt very threatened (8.1 per cent) than the youngest group (11.6 per cent) and a very similar proportion to the 61–75-year-old group (6.9 per cent). Overall, these age differences were small: in each age group, less than half of respondents felt slightly threatened, and between 7 and 12 per cent felt very threatened.

Source DEAS 2020 (n = 4739), weighted analyses, rounded estimates. Group differences statistically significant for age and self-rated health (p < 0.05)

Perceived threat from the Covid-19 pandemic according to age, gender, education, infections in the personal environment and self-rated health (in per cent).

When comparing women and men, it is noticeable that more men (51.4 per cent) than women (45.7 per cent) felt slightly threatened. However, slightly more men (9.6 per cent) than women (8.9 per cent) also felt very threatened. This gender difference was negligible, however, so women and men apparently felt threatened by the pandemic to a very similar extent.

There were also differences according to education: with increasing education, the proportion of people who experienced the pandemic as slightly threatening increased (people with low educational level: 41.8 per cent; medium educational level: 48.4 per cent; high educational level: 49.5 per cent). Moreover, among those with medium and high educational level (9.1 per cent and 8.8 per cent), there were fewer people who felt very threatened than among those with low educational level (12.7 per cent).

On the other hand, the experience of threat did not seem to have been affected by whether people had experienced Covid-19 in their immediate environment or not: in each case, around 50 per cent (Covid-19 cases in the environment: 47.6 per cent; no Covid-19 cases in the environment: 48.9 per cent) felt little threatened, and less than 10 per cent (Covid-19 cases in the environment: 9.7 per cent; no Covid-19 cases in the environment: 8.8 per cent) felt very threatened.

4.1 People with Poorer Self-Rated Health Experienced the Covid-19 Pandemic As More Threatening to Them Than People Who Rated Their Health As Good or Very Good

The differences in perceived threat were most pronounced according to self-rated health: while more than half (56.8 per cent) of people with very good or good self-rated health perceived the threat as low, among people with moderate to poor self-rated health, the proportion of people who perceived a low threat was significantly smaller, at 37 per cent. In this regard, the groups were 20 per cent points apart. Conversely, 5 per cent of people in very good to good health felt greatly threatened, while the proportion of people in moderate to poor health who felt greatly threatened was about three times as high, at 15.4 per cent.

5 Subjective Influence on the Risk of Contracting Covid-19

The majority of people felt they can influence the risk of contracting Covid-19, at least to a moderate degree.

The answers regarding the extent to which people felt they could influence their chances of contracting Covid-19 were distributed very unevenly across the seven possible answer categories (Fig. 4.3): While more than one in ten persons (12.2 per cent) gave values of 1 or 2—i.e. they thought they had a low influence—more than one in five (22.9 per cent) gave values of 6 of 7, which indicates high influence. Almost two-thirds (64.9 per cent) gave values between 3 and 5 and thus indicated moderate perceived influence. The most frequently reported score was 5 (32 per cent), while the extreme values 1 (no influence at all: 7.3 per cent) and 7 (complete influence: 6.1 per cent) were given by less than 10 per cent of respondents each.

Comparing these three groups (low, medium or high perceived influence on contracting Covid-19) according to various characteristics (Fig. 4.4), we noticed the following pattern: As far as age was concerned, the “young old” individuals aged between 61 and 75 years tended to rate their influence highest. In this group, a smaller proportion (9.3 per cent) perceived their influence as low than in the oldest group (16.5 per cent) and the youngest group (12.8 per cent). Among these “young olds”, there were also more people who perceived moderate influence (67.2 per cent) than among those aged 76 and over (60.8 per cent) and those aged 46 to 60 (64.7 per cent). In contrast, similar proportions of individuals perceived high influence in all three groups, ranging between 22 and 24 per cent.

Source DEAS 2020 (n = 4604), weighted analyses, rounded estimates. Group differences statistically significant for educational level and self-rated health (p < 0.05)

Subjective possibilities of influencing the risk of Covid-19 infection according to age, gender, education, infections in the personal environment and self-rated health (in per cent).

There were no differences in perceived influence between women and men. More than one in five women and one in five men believed they had a high influence on contracting Covid-19, while slightly more than one in ten women and one in ten men believed they had a low influence.

Education, on the other hand, did relate to perceived influence: While about 17 per cent of people with low and medium educational levels reported perceiving little influence over a possible Covid-19 infection, the corresponding proportion was 10 per cent points lower for people with a high educational level, at less than 7 per cent. On the other hand, more people with a high educational level perceived having moderate or high influence than people with low or medium educational levels.

Covid-19 cases in an individual’s personal environment were apparently less relevant for perceived influence: Slightly more people without Covid-19 in their environment perceived low influence (12.2 per cent) than people with Covid-19 in their personal environment (9.9 per cent). However, this was balanced out by the fact that more people without Covid-19 in their environment also perceived having a high influence (23.9 per cent) than among those with Covid-19 in their personal environment (17.8 per cent).

Finally, there were also differences in subjective influence depending on self-rated health: more people with good self-rated health (24.5 per cent) perceived having a high influence than those with poorer self-rated health (20.9 per cent). Likewise, more people (14.3 per cent) with moderate to poor self-rated health believed that they had a low influence on contracting Covid-19, while among people with very good or good self-rated health, the proportion was lower (10.6 per cent).

6 Associations between Perceived Threat and Subjective Influence on the Risk of Infection

Perceived threat and subjective influence were only weakly interrelated

How was the threat experience related to perceived influence on contracting Covid-19? There was a positive correlation (more perceived influence was associated with stronger threat experience), but the relationship was complex and not clear-cut (Fig. 4.5). More people in the moderate threat group perceived having a moderate influence (76.2 per cent) compared to those who indicated a low (58.3 per cent) or high (49.1 per cent) threat. Among the high threat group, more people perceived having a high influence (31.5 per cent) than in the other groups (low threat: 27.6 per cent; moderate threat: 15.8 per cent). At the same time, however, more people in this group experienced having a low influence (19.5 per cent) than in the other groups (low threat: 14.1 per cent; medium threat: 8 per cent).

7 Perceptions of the Covid-19 Crisis and Subjective Well-Being

People who felt more threatened by the Covid-19 crisis and who perceived having a lower influence on contracting Covid-19 were less satisfied with their lives and reported more severe depressive symptoms

People’s sense of threat due to the Covid-19 crisis and the extent to which they thought they could influence their likelihood of contracting Covid-19 might have been related to how satisfied they were with their lives and whether they experienced clinically relevant symptoms of depression. To investigate this, we compared the proportions of people with low, medium and high levels of perceived threat, and of people with low, medium and high levels of perceived influence on contracting Covid-19, who reported high levels of satisfaction with their lives and who had high levels of depressive symptoms.

There was indeed a substantial correlation (Fig. 4.6): the lower the perceived threat from the Covid-19 crisis, the higher the proportions of respondents who reported high life satisfaction. More than 80 per cent of respondents with low perceived threat were very satisfied with their lives, compared to only about 50 per cent of respondents with high perceived threat—a difference of more than 30 per cent points. The differences in depressive symptoms were similarly marked: while less than 10 per cent of respondents in the low threat group reported pronounced symptoms, more than five times as many, 37.6 per cent, reported pronounced depressive symptoms in the high threat group.

Differences in well-being depending on subjective influence on contracting Covid-19 virus were not quite as large but also striking (Fig. 4.7). Significantly more people who reported a high subjective influence were very satisfied with their lives (81.3 per cent) than among those who reported low subjective influence (65.1 per cent). Similarly, among those who reported having low influence, people with pronounced symptoms of depression were almost twice as prevalent (18.2 per cent) compared to those who perceived a high subjective influence (10.7 per cent).

8 Conclusion

The results on perceived threat and subjective influence on contracting Covid-19 show that most people, about 91 per cent, felt only a low to moderate degree of threat due to the pandemic, and most people (88 per cent) perceived themselves as having a moderate to high influence on their capacity to protect themselves from contracting Covid-19. However, the results also show that about one in ten people reported feeling a high level of threat, and likewise more than one in ten people reported having little influence over a possible infection with Covid-19.

How can we characterise those who felt highly threatened by the pandemic? People with higher levels of education felt mildly threatened by the Covid-19 crisis than people with a lower educational level. In contrast, the factors age, gender, and Covid-19 cases in the individual’s own environment hardly differed for people with a higher vs. a lower threat experience. This also means that, at every age and among both men and women, there was a proportion of people of about 10 per cent or more who felt very threatened.

People in middle adulthood did not necessarily feel less threatened than older people. This may seem surprising at first glance, since older people objectively have a higher risk of severe and even fatal Covid-19. Nevertheless, for the most part, older people were seemingly able to cope with the threat without too much worry. Life experience and experiences of previous crises may have helped older people to not feel too threatened. This has also been confirmed by other studies that show that fear of Covid-19 was relatively independent of age (e.g., Pearman et al. 2020).

This also suggests that even if people face a growing risk of severe Covid-19 as they get older, it is unhelpful to adopt a paternalistic attitude towards older people and even to generally stigmatise them as a particularly vulnerable and homogeneous group. Ultimately, all population groups require protection from Covid-19, because other age groups—including those below the ages of 50 to 60, which is the point at which people have a higher risk of severe Covid-19 (Robert Koch Institute 2020)—may face significant risks (for instance, due to certain previous illnesses). Likewise, all population groups should contribute to protecting others and themselves. At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, some feared an increase in ageism and intergenerational conflict (Ayalon et al. 2020; Ehni and Wahl 2020; Meisner 2021); there are now findings available that confirm these fears (Jimenez-Sotomayor et al. 2020). Ageism and pessimistic societal images of ageing negatively affect how people experience their own ageing, and this in turn has detrimental consequences on well-being, health and even life expectancy (Levy et al. 2020; Westerhof and Wurm 2015). Thus, it is important that policy-makers and the media counteract one-sided images of ageing that overemphasise the vulnerability of older people. On the contrary, most older people were able to cope with the crisis and were not more worried than younger people.

When it comes to perceived influence on therisk of contracting Covid-19, the following age pattern emerged: apparently “young olds” (61–75 years) perceived themselves as having greater influence than “old olds” (over 75 years) but also than people in middle adulthood (46–60 years). Education also played a role in perceived influence: people with higher educational levels were more likely to believe that they had an influence on their chances of contracting Covid-19. In fact, having a higher educational level was associated with certain protective factors, such as the option to work from home (Schröder et al. 2020). More should be done to ensure that people with lower educational levels, who often work in more exposed occupations, also have a lower objective and perceived risk of contracting Covid-19. In addition to working from home, this could include protective measures for certain occupational groups—for instance, high-quality protective equipment such as masks and rapid tests in facilities that are particularly at risk.

The role of self-rated health in threat experience and subjective influence

Self-rated health was more strongly related to the experience of threat and influence than any other factor: people who felt less healthy also experienced the pandemic as more threatening and saw fewer opportunities to avoid contracting Covid-19. This is plausible, as people who feel less healthy are generally also objectively less healthy, and certain pre-existing conditions are indeed a risk factor for severe Covid-19 (Robert Koch Institute 2020). Self-reported health status and concerns about one’s own health were thus found to be highly relevant for fears and threat experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic (Jungmann and Witthöft 2020; Traunmüller et al. 2020). Therefore, people with poor self-rated health should continue to receive optimal medical care and treatment for the entire duration of the Covid-19 pandemic. In everyday life, too, these people with health problems should be supported in minimising their risk of infection. Measures such as wearing masks and keeping minimum physical distance help to protect this group of people as well—if they are followed consistently and by everyone.

The connection between threat experience and subjective influence

Interestingly, threat perception and perceived influence were relatively independent of each other. In fact, slightly more people tended to perceive themselves as having a significant influence on their risk of infection when they felt more threatened. People with a high threat perception may have been particularly consistent in terms of protecting themselves by wearing masks and keeping a distance to others, such that they perceived themselves as having a greater influence on their risk of infection. At the same time, however, the very threatened group also had the highest proportion of people who perceived themselves as having a low influence on their risk of contracting Covid-19, which shows that the relationship between both variables is complex. People who were confident that they would not contract Covid-19 might still have felt threatened, because the pandemic may not have only been a threat to health, but also to individuals’ jobs, financial situations or social relationships.

What did the experiences of high or low threat mean in the pandemic? In general, people tended to overestimate their risk of contracting life-threatening Covid-19 (Hertwig et al. 2020). This may have had positive effects because these people might have been particularly careful in their everyday lives and protected themselves more consistently against possible infection. On the other hand, excessive worry could have endangered mental health. Balanced information about the threat posed by Covid-19 from both policymakers and the media is therefore crucial. Recklessness and panic within the population should be avoided. Moreover, those who felt well informed about Covid-19 and who were satisfied with the available information also tended to be less afraid of the virus (Jungmann and Witthöft 2020; Traunmüller et al. 2020).

Perception of the Covid-19 crisis and subjective well-being

Individuals with very strong threat perceptions and very low subjective influence were more psychologically distressed, as suggested by other studies conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic (Kivi et al. 2020; Losada-Baltar et al. 2020; Zacher and Rudolph 2020). Our findings also show that well-being—operationalised via life satisfaction and depressive symptoms—was lower among those who felt more threatened by the pandemic and who perceived themselves as having less influence on contracting Covid-19. Even if it is certainly appropriate to avoid trivialising threats and being careless, pandemic-induced increases in worries may have had negative consequences for quality of life. Our results show that this affected about 10 per cent of people in the second half of life who felt very threatened and who experienced little control over the possibility of contracting Covid-19 and who also reported lower life satisfaction and more severe depressive symptoms. However, depressive symptoms may have also led to an increased experience of threat, or both factors may have influenced each other.

Summary

Most people in the second half of life did not feel overly threatened by the pandemic, and most also perceived themselves as having a certain capacity to influence their chances of contracting Covid-19. Nevertheless, there were people in every population group who felt more threatened and believed they had less influence over contracting Covid-19.

Differences in the experience of threat and influence were only weakly related to age. Instead, those who felt less healthy also felt more threatened by the pandemic and were more likely to believe they had little influence on contracting Covid-19. Low- and medium-educated individuals also perceived themselves as having less influence on contracting Covid-19 than highly educated ones. These individuals with poorer self-rated health and with lower educational levels might need better support to minimise their risk of contracting Covid-19. Medical help that leads to better—perceived and objective—health may be just as important as measures to promote a higher personal impact on contracting Covid-19 (e.g. working from home, support from others with grocery shopping etc.).

Note that these results are a snapshot from the summer (June and July) of 2020. During this period, many of the measures to contain the virus had already been relaxed and the number of people who had contracted Covid-19 was low. This certainly contributed to the fact that few people felt very threatened by the pandemic in June and July 2020. Experiences of threat and control are dynamic and very likely highly dependent on underlying conditions such as current case numbers and trends. Repeated measurements are therefore needed to map these dynamics and to better understand which factors predict changes in threat and control experiences as the Covid-19 crisis continues.

Notes

- 1.

This question was originally developed by the Mannheim Corona Study of the German Internet Panel (GIP; https://www.uni-mannheim.de/gip/corona-studie/), and the original wording was minimally adapted in this study.

- 2.

This question was also introduced by the Mannheim Corona Study of the German Internet Panel (GIP; https://www.uni-mannheim.de/gip/corona-studie/) and was used here in an adapted form.

- 3.

This question was also asked in a similar wording in other studies (e.g., Mannheim Corona Study; COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO)).

- 4.

The “Don’t know” category was only very rarely selected (in 3.5 per cent of the cases) and was therefore not taken into account in the following evaluations.

References

Ayalon, L., Chasteen, A., Diehl, M., Levy, B., Neupert, S., Rothermund, K., Tesch-Römer, C., & Wahl, H.-W. (2020). Aging in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Avoiding Ageism and Fostering Intergenerational Solidarity. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa051

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Ehni, H. J., & Wahl, H. W. (2020). Six Propositions against Ageism in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4–5), 515–525.

Hertwig, R., Liebig, S., Lindenberger, U., Wagner, G. G. (2020). Wie gefährlich ist COVID-19?: Die subjektive Risikoeinschätzung einer lebensbedrohlichen COVID-19-Erkrankung im Frühjahr und Frühsommer 2020 in Deutschland. Berlin, Germany: German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), DIW Berlin.

Jimenez-Sotomayor, M. R., Gomez-Moreno, C., & Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E. (2020). Coronavirus, Ageism, and Twitter: An Evaluation of Tweets about Older Adults and COVID-19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8), 1661–1665. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16508

Jungmann, S. M., & Witthöft, M. (2020). Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: Which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102239

Kivi, M., Hansson, I., & Bjälkebring, P. (2020). Up and About: Older Adults’ Well-being During the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Swedish Longitudinal Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa084

Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Chang, E.-S., Kannoth, S., & Wang, S.-Y. (2020). Ageism Amplifies Cost and Prevalence of Health Conditions. The Gerontologist, 60(1), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny131

Losada-Baltar, A., Jiménez-Gonzalo, L., Gallego-Alberto, L., Pedroso-Chaparro, M. d. S., Fernandes-Pires, J., & Márquez-González, M. (2020). “We Are Staying at Home.” Association of Self-perceptions of Aging, Personal and Family Resources, and Loneliness With Psychological Distress During the Lock-Down Period of COVID-19. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa048

Meisner, B. A. (2021). Are You OK, Boomer? Intensification of Ageism and Intergenerational Tensions on Social Media Amid COVID-19. Leisure Sciences, 43(1–2), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773983.

Pearman, A., Hughes, M. L., Smith, E. L., & Neupert, S. D. (2020). Age Differences in Risk and Resilience Factors in COVID-19-Related Stress. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa120

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Robert Koch Institute (2020). SARS-CoV-2 Steckbrief zur Coronavirus-Krankheit-2019 (COVID-19). Online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Steckbrief.html (Last retrieved 3.11.2020)

Schröder, C., Entringer, T., Goebel, J., Grabka, M. M., Graeber, D., Kroh, M., Kröger, H., Kühne, S., Liebig, S., Schupp, J., Seebauer, J., & Zinn, S. (2020). Erwerbstätige sind vor dem Covid-19-Virus nicht alle gleich. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 1080.

Stafford, N. (2020). Covid-19: Why Germany’s case fatality rate seems so low. BMJ, 369, m1395. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1395

Traunmüller, C., Stefitz, R., Gaisbachgrabner, K., & Schwerdtfeger, A. (2020). Psychological correlates of COVID-19 pandemic in the Austrian population. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1395. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09489-5

Vogel, C., Klaus, D., Wettstein, M., Simonson, J., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2020). German Ageing Survey (DEAS). In D. Gu & M. E. Dupre (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69892-2_1115-1

Westerhof, G. J., & Wurm, S. (2015). Longitudinal Research on Subjective Aging, Health, and Longevity: Current Evidence and New Directions for Research. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 35(1), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1891/0198-8794.35.145

Wolff, J. K., Tesch-Römer, C. (2017). Glücklich bis ins hohe Alter? Lebenszufriedenheit und depressive Symptome in der zweiten Lebenshälfte. In: Mahne, K., Wolff, J., Simonson, J., Tesch-Römer, C. (eds) Altern im Wandel. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-12502-8_11

Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2020). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wettstein, M., Vogel, C., Nowossadeck, S., Spuling, S.M., Tesch-Römer, C. (2023). How did Individuals in the Second Half of Life Experience the Covid-19 Crisis? Perceived Threat of the Covid-19 Crisis and Subjective Influence on a Possible Infection with Covid-19. In: Simonson, J., Wünsche, J., Tesch-Römer, C. (eds) Ageing in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic . Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-40487-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-40487-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-40486-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-40487-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)