Abstract

Although marriage and cohabitation appear to be increasingly equivalent across Western countries, extensive research has demonstrated that married and cohabiting individuals still differ in terms of attitudes and well-being. Married people tend to express higher life satisfaction and more traditional opinions and values, whereas cohabiters tend to report more depressive symptoms and a more egalitarian division of tasks. Little is known about the roots of these differences. This study focus on the Swiss Household Panel subsample of respondents who lived together before they married. Its aim is to understand whether degrees of traditionalism and happiness might exist prior to marriage or, alternatively, whether it is the transition to marriage that implies changes in happiness and traditional values. Results tend to demonstrate that individuals have a high probability of responding similarly before and after the transition to marriage and validate the former hypothesis. However, results also show that the variables that play a key role before the marriage do not necessarily play the same role after. That means that marriage contributes to changing the way people assess different domains of their life as well as the hierarchy of the importance of the sociodemographic characteristics that influence individuals‘ subjective well-being, and opinions or attitudes toward family.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

A large body of literature describes differences between married and cohabiting couples in terms of attitudes or opinions about family and in terms of well-being, and conjugal quality (Brown 2000, 2004; Bumpass et al. 1991; Clarkberg et al. 1995; Diener et al. 2000; Jose et al. 2010; Nock 1995; Ryser and Le Goff 2015; Soons and Kalmijn 2009; van der Lippe et al. 2014; Wiik et al. 2009). Cohabitants tend to be less traditional in terms of the status and role of each partner in the family than married couples, but they also tend to be less happy. It has been argued that the lower level of well-being and the relationship instability might come from a lack of institutionalization of the cohabiting unions (Nock 1995). This lack of institutionalization leads to fewer institutional guidelines and fewer legal responsibilities for cohabitants than for married couples. Less traditional family values means that partners must discuss, and negotiate more in the relationship (Wilcox and Nock 2006). As a consequence, the relation between both partners is less peaceful than in a traditional marriage in which roles and status are well attributed (Cherlin 2004) and less likely to be objects of discussion.

In Switzerland, cohabiting is very often a prelude to marriage, which means that most couples experience the two statuses of cohabitant and spouse during their family lifecycles (Le Goff et al. 2005; Ryser and Le Goff 2011). What does it mean in regard to the general observations on traditionalism and happiness? Does it mean that the marriage as the marker of the transition from one status to the other is also a marker of the transition to more traditionalism and happiness? Or does it mean that couples share traditional values before the marriage and that the marriage is the result of a complex social mechanism of selection? To answer these questions, we will investigate Swiss Household Panel (SHP) data that concern cohabiting couples who get married. Our aim is then to compare the levels of traditionalism and life satisfaction before and after the marriage. In the following section, we review the literature in order to precise our research question and hypotheses. We then describe the data and measures we selected. We will then present the results and end with a general discussion of those results.

Married and Cohabiting Couples: To What Extent Do They Differ?

The end of the baby boom coincides with the emergence of a new demographic regime in most Western countries. This new regime can be schematically characterized by a high level of cohabiting unions, a high level of out of wedlock births, and a high level of divorces as well as late motherhood and high rates of infertility (Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 1988; van der Kaa 1987). These demographic trends indicate a context of the pluralization of unions that followed the monopoly of romantic marriage during the fifties and sixties. Long- or short-term cohabitation (Toulemon 1996), single parents, and couples who live apart coexist with the more traditional model of the conjugal couple (Regnier-Loilier et al. 2009; Villeneuve-Gokalp 1997). Nevertheless, in this new context of lifestyle pluralization, some types of union seem to be much more predominant than others, especially married couples and cohabiting couples.

In the specific case of Switzerland, cohabiting unions have quickly diffused since the early seventies. For several decades, this form of union served as a prelude to marriage (Le Goff et al. 2005; Sobotka and Toulemon 2008). In the early 1990s, 80% of union began as non-marital union (Gabadinho 1998) but 5% of children were born out of wedlock. At that time, Switzerland’s situation in Europe was rather particular since northern European countries were characterized by high rates of cohabitation and out-of-wedlock children, whereas southern European countries were characterized by low rates of cohabitation and out-of-wedlock children (Le Goff et al. 2005). The situation of cohabiting unions predominantly serving as a prelude to marriage can be partly explained by the fact that married and cohabiting parents did not have the same rights (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen 2012). In addition, childbearing within cohabitation was perceived as leading to the requirement of complicated administrative procedures for men to obtain parental rights, especially by unmarried fathers (Le Goff and Ryser 2010; Ryser and Le Goff 2011).Footnote 1

Trends show that since the end of the nineties, there has been a slow but steady increase of non-marital births in Switzerland. In 2014, almost one birth in four was out of wedlock. Nearly all out-of-wedlock children were born to women living in cohabiting unions. Such an increase shows that cohabiting unions seem to have become, at least partly, an alternative to marriage, especially in urban areas. In addition to this trend, some institutional changes to the law on parental authority introduced in 2014 have made the recognition of parental authority easier for an unmarried father.

As mentioned in the introduction of this chapter, researchers have highlighted the differences between married couples and those living in cohabiting unions. On the one hand, cohabiting partners tend to share less traditional values, opinions, and attitudes than married partners (Clarkberg et al. 1995; Le Goff and Ryser 2013; Ryser and Le Goff 2015). On the other hand, cohabiting individuals expressed higher levels of depressive symptoms and less happiness than their married counterparts (Brown 2000; Diener et al. 2000; Soons and Kalmijn 2009). These differences are often interpreted as poorer relationship quality and lower conjugal commitment for cohabiting couples in comparison to married couples (Brown 2000; Nock 1995). However it has been shown that the degree to which cohabitation is accepted in a defined country plays a key role in the degree of well-being differences between cohabitant and married individuals (Diener et al. 2000; Soons and Kalmijn 2009). In addition Schultz Lee and Ono (2012) demonstrated that in the most gender-egalitarian countries there was no statistically significant gap in the happiness of married and cohabiting women as opposed in more traditional countries.

The SHP data show results similar to those observed in other Western countries. Less conservative values are associated with a lower level of well-being among cohabitants in comparison to married couples (Le Goff and Ryser 2013; Ryser and Le Goff 2015).

Cohabiting unions can play different roles in the life course (Manting 1996), which we can divide into two main categories. First, a cohabiting union can be a prelude to marriage, or a trial period before the couple decides to marry. Second, cohabiting unions can be alternatives to marriage due to partners’ ideals or economic reasons (Perelli-Harris and Gerber 2011). Cohabitants who report that they plan to marry their current partner within two years differ much less from married individuals than cohabitants with no marriage plans. Brown (2004) adds that cohabitants with marriage plans tend to be happier than cohabitants that do not plan to marry. Such results suggest that the level of well-being is related to a process of selection of couples among those who plan to marry and those who do not. We also expect that this process of selection plays a role in traditional values, i.e., that couples who marry already shared traditional values before marriage.

The SHP allows us to further investigate this hypothesis of selection in the case of Switzerland. Rather than taking into account couples who plan to marry and comparing them with those who do not, SHP data allows us to follow cohabiting couples who got married in the 2000s and the beginning of the 2010s. Levels of traditionalism and of well-being for each partner are measured using the same protocol before and after the marriage. If the marriage results of a process of selection of conservative partners, levels of traditionalism and parallel the level of well-being should not evolve a great deal. The alternative hypothesis is that the marriage has an impact on the union and that partners become happier and more traditional. A rationale for this alternative hypothesis is that marriage might imply a reorganization of individual values and could promote conservative gendered norms and standards, which could explain the differences identified between married and cohabiting individuals in terms of beliefs, attitudes and gendered practices. This assumption is based on the fact that marriage is perceived by the individuals as the fulfillment of a strong symbolic rite that is largely related to belonging to a local community (Bozon 1992; Bozon and Héran 2006), family, or friend group. This sense of belonging to a specific group, consciously or unconsciously, could contribute to traditional norms and may subject married individuals to a certain social pressure (Théry 1998). It could push them over to traditionalism at the level of individual social representations as well as at the level of their practices.

Data, Sample and Method

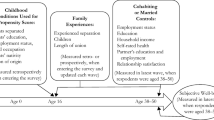

Data and Sample Description

Our investigations are based on a subsample of the SHP dataset. As questions of interest have only been available since 2002, we used data starting from that year. To assess the influence of the transition to marriage, we selected individuals aged 18 to 75 who declared themselves to be cohabitants at the wave n and who then declared themselves to be married at waves n + 1 and n + 2. The analysis was conducted on a total of 608 individuals—302 men and 306 women—who declared themselves married at some point after they began living with their partners.

Table 4.1 provides not weightedFootnote 2 information about the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Descriptive statistics show that the arrival of children is often linked with the transition to marriage. In addition, results demonstrate an increase in part-time work after the transition to marriage, mostly for women. This result can be explained by the fact that marriage is often linked with the transition to parenthood. During this transition, women reduce the amount of time they devote to work (Levy et al. 2006).

Variables

Dependent Variables

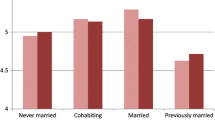

Our different dependent variables are related on the one hand to the well-being of people and on the other hand to their degree of traditionalism in regard to the family. We selected in the SHP three repeated measures of well-being and one measure of traditionalism. All chosen indicators were initially measured using an 11-point scale from 0 to 10. We recoded these dependent variables into dummy variables in order to estimate logistic models.

Subjective Well-being

We took three domains of satisfaction into account — satisfaction with life in general, living together, and the relationship. A t-test indicates that the transition to marriage seems to negatively impact satisfaction with the relationship (t(352) = 2.678, p = 0.008).

Family Opinion

One item measures the respondent’ opinion of the statement that a child suffers if he/she has a working mother on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (completely disagree) to 10 (completely agree). A t-test shows that the transition to marriage seems to impact this statement. Individuals tend to agree less with this statement after the transition to marriage (t(247) = 3.957, p = 0.000).

Sociodemographic and Control Covariates

Education

Respondent’ level of education is established with a categorical variable that accounts for the highest level of education achieved. It distinguishes between low levels (e.g., incomplete compulsory school, compulsory school, elementary vocational training, domestic science courses, one-year commerce school, and general training school), middle levels (e.g., apprenticeship, technical or vocational school, full-time vocational school, vocational high school with a master’s certificate, and federal certificate), and high levels (e.g., vocational high school, university, and academic high school) of education.

Income

An indicator accounts for the yearly net household income (for a detailed description of the income variables, see Lipps 2010). In the analyses, we introduced the log form of the household income. A t-test indicates that the level of household income did not change before and after marriage (t(531) = 0.414, p = 0.679).

Number of Children

We distinguish between zero, one, two or more children. Marriage is associated with more children than cohabiting union, as shown by the t-test: t(606) = −19.044, p < 0.000.

Age

To determine any differences in the ages of the SHP-participants, we controlled for age.

Analytical Strategy

The aim of our research was to better understand to what extent the set of dependent variables might differ for individuals before and after the transition to marriage. This means that the research deals with paired outcomes. In the present case, a pair of outcomes (Yt1, Yt2) corresponds to a repeated dichotomized measure for one respondent, the first outcome being measured before the marriage (t1) and the second after (t2). We can suppose that the observations within pairs are not independent, whereas observations from different pairs are independent (Le Cessie and Van Houwelingen 1994). The potential dependence between the two outcomes in a pair of measures would be especially true for the hypothesis that there is a process of selection for the sample of cohabiting persons who marry. In order to capture this potential dependence between two outcomes, we estimated a series of bivariate logistic models, one for each of the pairs of dependent variables (Palmgren 1989; Yee 2010; Yee and Dirnböck 2009). The principle of that kind of model is to simultaneously estimate an odds ratio for each independent covariates on each outcome as well as a coefficient of association between both outcomes. This last coefficient is estimated by a new odds ratio term which corresponds to the product of probabilities to obtain the same outcome for an individual divided by the product of probabilities that the two outcomes are different. The model can be written:

where Xt1 and Xt2 are vectors of covariates measured before and after the marriage, respectively (level of education, age, etc.); b1, b2 and b3 are intercepts to be estimated; and a1 and a2 are vectors of estimated coefficients attached to the covariates Xt1 and Xt2. The outcome b3 = 0 means that the two outcomes are independent, whereas b3 > 0 means a positive dependence between them, i.e., the respondent will persist in giving a similar response after marriage. A positive association between the two outcomes would support the hypothesis of a process of selection of cohabiting couples that get married. We do not expect to observe the case of b3 < 0, which would correspond to the case in which the two outcomes are negatively associated—for example, that a low level of satisfaction before marriage would be associated with a high rate of satisfaction after or vice versa. Models are estimated for each pair of dependent variables using the library VGAM in R-Cran (Yee 2010; Yee and Dirnböck 2009).

Results

Table 4.2 displays the results for the different measures of satisfaction with life in general, with the relationship and with living together. In each case, there is a strong association between the measure before and after the marriage (as estimated by b3 coefficients). Such a result indicates a process of selection related to marriage.

The patterns of the results demonstrate that sometimes, covariates that play a key role before marriage do not necessarily play the same role afterward and vice versa. That means that in certain cases, the transition to the married status contributes to attenuating or exacerbating the way people assess their satisfaction according to their characteristics. In that sense, these results allow us to say that marriage does to some extent shape individuals’ evaluation of their satisfaction.

Women tend to be more satisfied with life in general than men before the transition to marriage. In addition, highly educated individuals tend to be more satisfied with life than individuals with a middle level of education. These differences disappear after marriage.

In terms of satisfaction with the relationship, women are more satisfied with the relationship than men before as well as after the transition to marriage. Having two or more children before marriage decreases the level of satisfaction with the relationship. Differences in the level of satisfaction disappear after the marriage.

After the transition to marriage, older individuals are less likely to express satisfaction with living together. A high level of education leads to less satisfaction with living together in comparison to a middle level of education. Finally, children play a key role in shaping the level of satisfaction with living together. Results are not significant before marriage, though the estimated coefficients before marriage are very similar to those estimated after marriage. We suppose however that this lack of significance can be related to the lack of couples having one child or more children before marriage. Having two children or more before the transition to marriage seems to be associated with a reduction of satisfaction with living together compared to having no children. After the transition to marriage, having one or more children is also linked with a decrease in satisfaction with living together. Here again, the impact of the children on the satisfaction with the relationship did differ after the transition to marriage.

Table 4.3 displays the results of the respondents’ opinion of the statement that a child suffers if the mother works. As before, the general pattern is that individuals have a high probability to give the same answer before and after the transition to marriage.

Results by covariate show that women at times 1 and 2 are less likely than men to express that children with working mothers suffer before as well as after the marriage. In addition, individuals with higher levels of education are less likely to express that children with working mothers suffer. In this dimension, it seems that marriage does not shape individuals’ opinion of that statement. These results thus confirm the idea of a selection effect.

Conclusion

The main aim of the present research was to explore to what extent marriage might imply more conservative values and practices (Théry 1998) and higher levels of well-being that lead to differences between married and cohabiting couples. The first hypothesis postulates that individuals who decide to get married already share more gendered values and practices that lead to the observed differences between married and cohabiting couples. Alternatively, the second hypothesis postulates that the transition to marriage could imply more gendered practices. Based on the methodology of modeling bivariate binomial responses (Yee 2010; Yee and Dirnböck 2009), the main results of our research tend to demonstrate that individuals have a high probability of responding similarly before and after the transition to marriage on measures of their well-being and values. This suggests that the differences between married and cohabiting individuals might not come from the transition to marriage per se but that they seem to exist before marriage. To summarize, the results tend to indicate that there is a form of selectivity among couples. Individuals who decide to get married already share more traditional perspectives on family practices and beliefs and have already made changes in their level of well-being. It might be a reason to explain why little difference between before and after marriage is observed in the study.

This study is of importance because it questions the origin of the highlighted differences between cohabiting and married individuals. However, it has some limitations. The first one is the relatively small numbers of married individuals included in the analyses. A larger group would lead to more robust results and allow for the study of gender differences. For the current study, the small number of men and women did not allow us to highlight these differences. A second limitation resides in the highly selective SHP subsample we investigated. The high proportion of highly educated individuals does not favor the study of dynamics for individuals with fewer resources. Despite these limitations, our study provides some results about the mechanisms that lead to the well-known differences between cohabiting and married individuals. Further research should also better tackle these questions by taking into account the heterogeneity of the cohabitation and comparing cohabitant who marry with those who do not marry (Hiekel and Castro-Martín 2014). This could become of importance in Switzerland as more and more couples decide to remain unmarried when they have children.

Notes

- 1.

Since 1 July 2014, joint parental right became the rule. Currently data available do not allow studying the changes that might be led by this institutional change.

- 2.

Results have not been weighted because first, the analyses are based on a very peculiar subsample of SHP; second, because of the “experimental” dimension of our investigations: Variables are measured on each individual at two times of their life. As these two times are separated by an event, we want to see differences between these two times. In definitive, we do not have any pretention for a representative subpopulation of couples originally cohabitant that married during the period of investigation.

References

Bozon, M. (1992). Sociologie du rituel du mariage. Population (French Edition), 47(2), 409–433.

Bozon, M., & Héran, F. (2006). La formation du couple - Textes essentiels pour la sociologie de la famille. Paris: Grands Repères.

Brown, S. L. (2000). The effect of union type on psychological well-being: Depression among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 241–255.

Brown, S. L. (2004). Moving from cohabitation to marriage: Effects on relationship quality. Social Science Research, 33, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00036-X.

Bumpass, L. L., Sweet, J. A., & Cherlin, A. (1991). The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 913–927.

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of american marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x.

Clarkberg, M., Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Attitudes, values, and entrance into cohabitational versus marital unions. Social Forces, 74(2), 609–632.

Diener, E., Gohm, C. L., Suh, M. E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Similarity of the relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022100031004001.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 1–31.

Gabadinho, A. (1998). L’enquête Suisse sur la famille. Berne: Office fédéral de la statistique.

Hiekel, N., & Castro-Martín, T. (2014). Grasping the diversity of cohabitation: Fertility intentions among cohabiters across Europe. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(3), 489–505.

Jose, A., O’Leary, D. K., & Moyer, A. (2010). Does premarital cohabitation predict subsequent marital stability and marital quality? A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 105–116.

Le Cessie, S., & Van Houwelingen, J. (1994). Logistic regression for correlated binary data. Applied Statistics, 43, 95–108.

Le Goff, J.-M., & Ryser, V.-A. (2010). The meaning of marriage for men during their transition to fatherhood. The Swiss context. Marriage & Family Review, 46, 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494921003648654.

Le Goff, J.-M., & Ryser, V.-A. (2013). Mariage et union consensuelle avec enfant en Suisse. In D. Tabutin & B. Masquelier (Eds.), Ralentissements, résistances et ruptures dans les transitions démographiques (pp. 157–172). Louvain-La-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain, Acte de colloque chaire de Quetelet.

Le Goff, J.-M., Sauvain-Dugerdil, C., Rossier, C., & Coenen-Huther, J. (2005). Maternité et parcours de vie. Berne: Peter Lang.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Developpment Review, 14(1), 1–45.

Levy, R., Gauthier, J.-A., & Widmer, E. (2006). Entre contraintes institutionnelles et domestiques : Les parcours de vie masculins et féminins en Suisse. Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie, 31(4), 461–489.

Lipps, O. (2010). Income imputation in the Swiss Household Panel 1999–2007. FORS Working Paper Series, paper 2010-1. Lausanne: FORS.

Manting, D. (1996). The changing meaning of cohabitation and marriage. European Sociological Review, 12(1), 53–65.

Nock, S. L. (1995). A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 16(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251395016001004.

Palmgren, J. (1989). Regression models for bivariate binary responses. Technical Report no. 101. Seattle: University of Washington, Department of Biostatistics.

Perelli-Harris, B., & Gerber, T. P. (2011). Nonmarital childbearing in Russia: Second demographic transition or pattern of disadvantage? Demography, 48(1), 317–342.

Perelli-Harris, B., & Sánchez Gassen, N. (2012). How similar are cohabitation and marriage? Legal approaches to cohabitation across Western Europe. Population and Development Review, 38(3), 435–467.

Regnier-Loilier, A., Beaujouan, É., & Villeneuve-Gokalp, C. (2009). Neither single, nor in a couple. A study of living apart together in France. Demographic Research, 21(4), 75–108.

Ryser, V.-A., & Le Goff, J.-M. (2011). Le mariage en Suisse : Contrainte institutionnelle ou choix de vie. In S. Gouazé, A. Salles, & C. Prat-Erkert (Eds.), Les enjeux démographiques en France et en Allemagne : Réalités et conséquences (pp. 109–123). Lille: Septentrion.

Ryser, V.-A., & Le Goff, J.-M. (2015). Family attitudes and gender opinions of cohabiting and married mothers in Switzerland. Family Science, 6(1), 370–379.

Schultz Lee, K., & Ono, H. (2012). Marriage, cohabitation, and happiness: A cross-national analysis of 27 countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(5), 953–972.

Sobotka, T., & Toulemon, L. (2008). Overview chapter 4: Changing family and partnership behaviour: Common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demographic Research, 19, 85–138.

Soons, J. P. M., & Kalmijn, M. (2009). Is marriage more than cohabitation? Well-being differences in 30 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 1141–1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00660.x.

Théry, I. (1998). Couple, filiation et parenté aujourd'hui. Paris: Odile Jacob.

Toulemon, L. (1996). La cohabitation hors mariage s' installe dans la durée. Population (French Edition), 51(3), 675–715.

van der Kaa, D. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42(1), 1–59.

van der Lippe, T., Voorpostel, M., & Hewitt, B. (2014). Disagreements among cohabiting and married couples in 22 European countries. Demographic Research, 31(10), 247–274.

Villeneuve-Gokalp, C. (1997). Vivre en couple chacun chez soi. Population (French Edition), 52, 1059–1081.

Wiik, K. A., Bernhardt, E., & Noack, T. (2009). A study of commitment and relationship quality in Sweden and Norway. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(3), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00613.x.

Wilcox, W. B., & Nock, S. L. (2006). What's love got to do with it? Equality, equity, commitment and women's marital quality. Social Forces, 84(3), 1321–1345.

Yee, T. W. (2010). The VGAM package for categorical data analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 32(10), 1–34.

Yee, T. W., & Dirnböck, T. (2009). Models for analysing species’ presence/absence data at two time points. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 259(4), 684–694.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ryser, VA., Le Goff, JM. (2018). The Transition to Marriage for Cohabiting Couples: Does it Shape Subjective Well-being and Opinions or Attitudes Toward Family?. In: Tillmann, R., Voorpostel, M., Farago, P. (eds) Social Dynamics in Swiss Society. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 9. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89557-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89557-4_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-89556-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-89557-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)