Abstract

Between 1991 and today, the Soviet system of state-funded and Communist Party controlled higher education institutions (HEIs) in Kyrgyzstan has been transformed into an expansive, diverse, unequal, semiprivatized and marketized higher education landscape. Drawing on national and international indicators of higher education in Kyrgyzstan and data about the history and substance of these changes in policy and legislation, this chapter examines key factors which have shaped patterns of institutional differentiation and diversification during this period. These include the historical legacies of Soviet educational infrastructures, new legal and political frameworks for HE governance and finance, changes to regulations for the licensing of institutions and academic credentials, the introduction of multinational policy agendas for higher education in the Central Asian region, changes in the relationship between higher education and labor, the introduction of a national university admissions examination, and the adoption of certain principles of the European Bologna Process. The picture of HE reform that emerges from this analysis is one in which concurrent processes of diversification and homogenization are not driven wholly by either state regulation or forces of market competition, but mediated by universities’ strategic negotiations of these forces in the context of historical institutional formations in Kyrgyzstan.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kyrgyzstan is a small, mountainous, landlocked, and relatively poor country in Central Asia. It is bordered by China to the east, Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, and Tajikistan to the south and has a young, growing, and ethnically diverse population comprised of Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Russian, and German, Kazakh, Korean, Tajik, Tatar, Ukrainian, and other ethnic groups.Footnote 1 Following its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan experienced processes of change across all areas of social, political, and economic life. Higher education reform has been central to this agenda, and between 1991 and today, the Soviet-era system of state-funded and Communist Party-controlled higher education institutions (HEIs) in Kyrgyzstan has been transformed into an expansive, diverse, unequal, semiprivatized and marketized higher education (HE) landscape (Amsler 2011; Brunner and Tillett 2007; Mertaugh 2004; Narkoziev and Yanzen 2013). How should we make sense of these changes within the framework of institutional diversification?

Mindful of Fumasoli and Huisman’s (2013) arguments that the marketization of higher education does not necessarily generate institutional diversification, that government regulation does not necessarily lead to homogenization among institutions, and that universities’ own institutional strategies and responses to environmental changes shape processes of structural reform in complex ways, this chapter assesses the specific character of these changes to the landscape in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan. After briefly describing the structure and financing of higher education in the Kirgiz Soviet Socialist Republic (KSSR) from 1917 to 1991, we consider some key factors which have shaped patterns of the differentiation and diversification of HE in the post-Soviet period. These include the historical legacies of Soviet HE infrastructures, new legal and political frameworks for HE governance and finance, changes to regulations for the licensing of institutions and academic credentials, the introduction of new multinational policy agendas for higher education in the Central Asian region, changes in the relationship between higher education and labor, the introduction of a national university admissions examination, and the adoption of certain principles of the European Bologna Process. The picture of HE reform that emerges from this analysis is one in which concurrent processes of diversification and homogenization are not driven wholly by either state regulation or forces of market competition, but mediated by universities’ strategic negotiations of these forces in the context of historical institutional formations in Kyrgyzstan.

The analysis presented in this chapter focuses on trends, since 1991, in both ‘external diversification’ within the HE system (in which differences emerge between institutions) and ‘systemic’ and ‘programmatic’ differentiation, with particular attention to the relationship between this process and the dismantling, reinforcement, or emergence of hierarchy and stratification within the HE system. ‘Systemic differentiation’ refers to “differences in institutional type, size, and control found within a higher education system”, and ‘programmatic differentiation’ refers to the “degree level, degree area, comprehensiveness, mission and emphasis of programs and services provided by the institutions” (Huisman 1995, 13). The chapter draws on national and international statistical indicators of higher education and educational reform in Kyrgyzstan, and qualitative data about the history and substance of these changes drawn from legislation, regulations, and policy statements concerning this period of reform. Statistical information about each university’s structure, organization, and curricula during the post-Soviet period was obtained from the National Statistical Committee (NSC) of the Kyrgyz Republic; government educational databases from the Ministry of Education and Science (MoES), which is the main agency responsible for the quality of education and management of the education system in Kyrgyzstan; Accounting Chambers; the National Academy and National Testing Centre (for information about student enrollments) and institutional websites and annual reports.

The Development of Higher Education in the Kirgiz Soviet Socialist Republic

In the 1920s and 1930s, the new Soviet state implemented a violent process of forced settlement and collectivization in the KSSR and early Bolshevik programs for ‘civilizing’ the Central Asian steppe and incorporating its diverse tribal communities into a new empire included the creation of new universities and research centers in the region (Amsler 2007; Buyanin 2001); these existed side by side with traditional educational institutions such as the maktab and madrassa until the 1930s (Khalid 1999). Institutions of higher learning such as universities and filials of the Russian Academy of Science, which began to appear in Kirgizia in the 1930s following the establishment of the Central Asian University in Tashkent, Uzbekistan in 1920, were oriented primarily toward political and technical education rather than teaching or academic research and used as experimental sites for promoting literacy and disseminating pedagogies on science, politics and morality, or as ‘bases’ for Russian ethnographic and geographical research (Amsler 2007).

During the mid-Soviet period, due to large-scale campaigns for basic education which accompanied a process of rapid industrialization across the country, the literacy rate in the society jumped from 16.5% (1926) to 99.8% (1979) (Ibraimov 2001) and full systems of primary, secondary, professional, and higher education were created (Holmes et al. 1995; Shamatov 2015). By 1991, the country had 12 institutions of higher education, each of which served a different function within the educational system (Fig 9.1).

The structural framework for Kyrgyzstan’s educational system, like that in all Soviet republics, was shaped by centralized state policies in accordance with the country’s economic needs and principles believed to define a general socialist education, including the eradication of illiteracy, the provision of vocational instruction in secondary school, the massification of educational opportunities, and the incorporation of state ideology and moral education into the curriculum and training processes (Clark 2005). Decisions about governance, curriculum content and organization, student admissions, and so on were made by the Ministry of Education in Moscow and, until the late 1980s, were similar across the 15 Soviet republics (Amsler 2007; DeYoung 2011; Heyneman 2010).

Each higher education institution had its own ‘profile’ or portfolio of specialized functions and purposes within the system (Table 9.1; Fig. 9.2). Contrary to current definitions of institutional positioning in which ‘higher education institutions locate themselves in specific niches within the higher educational system’ (Fumasoli and Huisman 2013, 160), this profiling was the responsibility of the Soviet state. There was no duplication of programs offered by each institution, although teachers with similar specializations were distributed throughout all regions. The state built HEI each with a specialized, profile-appropriate campus; for example, the Medical Institute had a study campus and anatomy building, the Polytechnic Institute had state-of-the-art technical labs, and so on. However, financial resources were not distributed evenly across the sector, and HEIs were geographically stratified such that central institutions located in Frunze (now the capital city of Bishkek) were more likely to obtain funding from the Central Committee of the Communist Party than regional institutions with small student populations and lower-priority profiles.

The HEI landscape in Kyrgyzstan (Source: Authors using data from Orusbaeva 1982)

Student numbers were set by the State Planning Committee (Gosplan), which determined the demand for particular specializations in the national economy. All levels of education were state-funded, public and free of charge, and while enrollment was competitive it increased rapidly between 1965 and 1975 and then steadily until 1991 (Orusbaeva 1982; NSC 2012b; see Fig. 9.3). By the early 1990s, 58,023 students were studying across all HEIs in Kyrgyzstan—152 students per 10,000 citizens. As most of the institutions were located in Frunze, this urban center became the primary destination for higher education provision and many young people moved to the capital from rural locations across the country to obtain their qualifications.

By 1990, the formal higher education system in the Kirgiz Soviet Socialist Republic was thus both differentiated and externally diversified (as different types of institutions, courses environments, and educational programs had been created in response to state-defined political and economic needs) and homogenous (as this process was directed through state planning and regulation, and all HEIs were state institutions).

Independence and New Patterns of Differentiation and Diversification in Higher Education

In December 1992, a year after Kyrgyzstan gained independence from the Soviet Union, the government adopted a Law ‘On Education’ to reorient educational reform in the new political-economic context; in particular, “changing to diversified educational programmes, seeking new learning forms and technologies, arranging multi-channel funding, involving various partners in providing educational services and developing non-governmental education” (MoESYP 2006; Tiuliundieva 2008, 78). This was followed by a series of new laws and strategies aimed at structurally transforming the system along these lines.Footnote 3 HEIs thus became partially autonomous and able to implement independent policies in areas such as human resources, student performance evaluation, educational methodology and technology, the identification of scientific research areas, and the management of organizational, financial, and other issues in accordance with their statutes, memoranda, legal, and other regulatory acts. Within these parameters, however, the state remained responsible for many core activities including providing basic funding for higher education according to individual’s abilities and propensities (as determined by testing), setting standards for each level of formal education, approving priorities in curriculum development, training teachers, accrediting higher education institutions, collecting statistics on education, liaising with the National Academy of Sciences to set research priorities, and managing official international cooperation. Since independence, HEIs in Kyrgyzstan have remained accountable to the state for ‘quality assurance’ and must, at least formally, comply with its regulations in order to operate.

The new legal, financial and ideological frameworks for HE policy created conditions for a rapid diversification and expansion of the system, which grew from 12 HEIs in 1991 to 52 in 2015 (although this number can fluctuate from year to year as new institutions are opened and closed). This was accomplished in a variety of ways, including the establishment of new institutions in all regions of the republic; the creation of new branches, departments, and educational centers with legal status in existing institutions; and the reorganization of vocational institutions (technikums) into higher education institutions that had a broader remit to offer market-oriented programs. For example, in the 1990s, the accounting vocational institute (Frunzenskyi tecknicum sovetskoy torgovly) changed its status to become the Bishkek High Commerce College (1997), then the Institute of Bishkek State University of Economics and Business (1999), the Bishkek State Institute of Economics and Commerce (2003), and the Kyrgyz Economic University (2007) (see Table 9.2).

Today, the Kyrgyz state classifies its 52 higher education institutions into four categories based on their teaching and research profiles. Academies are educational institutions that offer training programs and conduct fundamental and applied scientific research (public, 6; private, 5). Universities are multi-profile institutions which provide a wide range of specialist training at all levels of higher education including academic and in-service training and which conduct fundamental and applied scientific research (public, 19; private, 7). Institutes may be either independent or units in universities carrying out higher education training for specialists and in-service training programs at all levels (public, 4; private, 6). Finally, ‘profiled HEIs’ offer more narrowly defined education and training programs in specific areas, such as the training of highly specialized experts in music or the military (conservatory, art and musical HEIs, 3; Military Institute of the Armed Forces and Interior HEI, 2). In this chapter, we offer a slightly more nuanced typology, focusing on processes of differentiation and diversification, which makes visible the impact of the emergence of new private and international HEIs (see Table 9.3).

On one hand, this systemic differentiation and external diversification of the institutional landscape has broadened the range of HEIs in Kyrgyzstan. On the other hand, however, the setting of national curriculum standards by the MoES and the state regulations for institutional licensing means that there are still parameters for the differentiation or diversification of HE as all programs, regardless of whether they are located in public or private institutions, must demonstrate compliance with these state standards. This limits the scope for HEIs to develop genuinely independent profiles, which in turn limits the degree of diversity within the system (Fumasoli and Huisman 2013; Huisman 1995; Van Vught 2008; Teichler 1988). Nevertheless, institutional expansion has been coupled with an increase in the overall number of students enrolling in higher education. Despite economic hardship in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan, public demand for higher education grew during the 1990s and has continued to do so to the present day, with nearly 40% of the current age cohort enrolling in higher education of some kind (NSC 2014b; Table 9.3).

According to official data (NSC 2008), student enrollment in HE reached its highest point in 2005 due to the growth in the number of HEIs in the country and the low cost of tuition fees (the average tuition fee being 8,000 Kyrgyz soms or USD $200 at the time). In 2008, however, more students began dropping out from universities due to the cost of tuition, and enrollments in vocational institutions—which charge lower fees, are more directly linked to employment, and offer shorter training periods—significantly increased (Fig. 9.4).

Secondary school graduates and student enrollment in vocational and higher education institutions, 1991–2013 (Source: Authors using data NSC 2014c)

In 2008, the enrollment of secondary school graduate students to HEIs decreased because the tuition fees increased to a minimum cost of 17,000 Kyrgyz soms ($360), and it became mandatory for students to submit their results from a new national admissions test to enroll in any university. Many graduates who did not pass the test found alternative pathways into higher education, such as enrolling in specialized colleges on the basis of their ninth-grade marks (see also DeYoung 2011, 44). Such colleges operate as parts of particular HEIs which do not require admission test scores because students take a special study program of study for credit and, upon completing it, continue two further years of study at the same HEI. Finally, secondary school graduates and their parents still often consider the 2-year Bachelor’s degree, a post-independence credential which was introduced as part of Kyrgyzstan’s efforts to join the Bologna Process, to be an incomplete higher education as compared with the Soviet 5-year specialized degree. This strategy for access has generated new relationships between vocational institutions and other types of HEI, and some institutions such as the Kyrgyz State University, Kyrgyz Technical University, International University of Kyrgyzstan, Slavonic University, and Bishkek Humanities University have internally diversified into multi-level complexes offering initial, secondary, and higher levels of vocational education.

Higher education in Kyrgyzstan also became more linguistically diverse after independence. With different logics of higher education reform operating in the country, from nation-building to regionalization and internationalization (Silova 2011), improving the quality of education in both a new national language (Kyrgyz) and English as well as Russian became a focus of educational policy. While post-independence language laws initially stipulated the development of national language literacy at all levels of education, with then-President Akayev signing a state language law in 2000, an acute lack of adequate textbooks, dictionaries, and teaching materials in Kyrgyz hindered the implementation of this policy (even the training manuals for the law were published in Russian). In 2013, although the legal status of state and official languages was altered again so that all official documents were to be prepared only in Kyrgyz, Russian remained the main language for most of the country’s higher education programs. Therefore, while the Kyrgyz language was used in primary and secondary schools in the 1990s, it was not used at the university level except in linguistic specialisms.

While some universities have dedicated programs in English (such as degrees in Medicine or Information Technology for international students), there remains a shortage of both teaching materials and instructors who can teach diverse subjects in foreign languages in universities across the sector. Some institutions do now offer dual-language courses in other strategic languages. International HEIs such as the American University of Central Asia, the Kyrgyz–Turkish Manas University, and the Ata Turk Ala-Too University offer programs in English or Turkish and have degrees recognized jointly by both governments (the KRSU and KTU Manas universities work more generally in a new institutional form of inter-governmental agreement, which gives them more money for facilities and demands comparatively looser government oversight).

The Bologna Process: An External Driver of Diversification in Kyrgyz Higher Education

The Bologna Process project of ‘harmonizing’ and standardizing university awards across Europe and affiliated world regions has, in Kyrgyzstan, led to a certain type of diversification of education programs and the development of new types of relationship for training, financing, and partnerships in the provision of education services with European HEIs. In 2004, the Kyrgyz government, through a Working Group of the President of the Kyrgyz Republic on the Integration of HEIs of Kyrgyzstan into the Bologna Process and the National Office of the EU Tempus–Tacis program, signed a Memorandum of Agreement to integrate its HEIs into the Bologna Process (National Tempus Office Kyrgyzstan 2016). A number of universities (the International University of Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek Academy of Finance and Economics, Kyrgyz Economic University, and Kyrgyz National University) subsequently adopted projects to implement the requirements of the Bologna Process. Despite being denied membership to the Bologna Process in 2007, owing to the fact that Kyrgyzstan was not party to the European Cultural Convention of the Council of Europe, Kyrgyzstan still aspires to join and the state continues to create reform policies which are informed by the principles of the Bologna Process in order to increase opportunities for joint projects and international mobility among students and academic staff.

For example, the Bologna agenda had a significant impact on the structure of academic degree courses within the Kyrgyz higher education system, and on the status of existing and newer degree holders. Today, the Soviet-era two-cycle system, which consists of a specialist diploma degree and an advanced aspirantura, co-exists with the Bologna three-cycle system, which prepares students at Bachelor’s, Master’s, and PhD levels. While recognized PhD enrollment in Kyrgyzstan began only in 2013 in a small number of HEIs (e.g., the Kyrgyz–Turk Manas University, Kyrgyz National Agrarian University, and International University of Kyrgyzstan), by 2012 the MoES required all higher education institutions to offer Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in order to enable future compliance with the Bologna Process. Seven HEIs are now licensed by the MoES to offer all three tiers of educational programs and seven to offer MAs, and while all universities offer BA programs, only ‘profiled’ HEIs can offer MA and PhD programs. The status of the PhD degree itself remains ambiguous in the country and at present only a few universities offer it, while the aspirantura award is still widely available. Such programs are thus offered alongside traditional 5-year specialized degrees in many parts of the country, although with more universities reducing these programs as required by government decree (Government of the Kyrgyz Republic 2011).

These courses are not, however, distributed evenly throughout the system and their availability varies across disciplines: Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees are in greater demand in economic and humanitarian fields, whereas within industry and agriculture, priority is still often given to specialists with what is considered ‘full’ (i.e., 5-year) higher education. Such degrees will thus remain part of the system for the foreseeable future and will not be shut down entirely, as according to a recent government resolution on education, by 2020 the proportion of students within the country’s universities should be 70% BA, 20% MA, and 10% specialist (Government of the Kyrgyz Republic 2012). Yet the differential value between these Bologna-compliant credentials and the previous two-tier cycle of awards, combined with the emergence of competition for students in public and private institutions alike, has become influential as a criterion for making hierarchical distinctions between the country’s higher educational institutions. These different levels of license thus contribute to both diversification and vertical differentiation within the system, which in turn influences future developments in the academic profile, infrastructure, and focus of teaching and research within each institution.

Forces and Factors of Vertical Differentiation

The National Scholarship Test for University Admission

The higher education landscape in Kyrgyzstan has also been reshaped by the introduction of a National Scholarship Test, which is administered by a national testing center that is independent from both the MoES and individual HEIs. Kyrgyzstan was the first state in Central Asia to introduce a merit-based national university admission exam (following, in the wider CIS region, Azerbaijan in 1992 and Russia in 2001; see Drummond and Gabrscek 2012). It was introduced in 2002 in order to create a more transparent system for distributing state scholarships (National Tempus Office Kyrgyzstan 2016) and to replace institutional-based admission practices that had become regarded as problematic in the post-Soviet period because allowing universities to fill government-allocated student quotas and distribute government scholarships enabled some to be discriminatory, corrupt, and ineffective (Blau 2004; Heyneman et al. 2008; Mertaugh 2004; Osipian 2007; Shamatov 2012). From 2004, a new Center for Educational Assessment and Teaching Methods (CEATM), funded by the United States Agency for International Development, assumed responsibility for administering this exam. In 2012, the MoES made it mandatory for all students to have a national test certificate in order to enroll on any program, and the 50 applicants with the highest test scores from across the country receive a certificate enabling them to enroll in the discipline and university of their choice without further examination (National Tempus Office Kyrgyzstan 2016).

The National Scholarship Test (NST) has had dual implications for the structure of the higher education system in Kyrgyzstan. On the one hand, it is regarded as having the potential to reduce practices of corruption in university admissions processes and increase the participation of students from historically underrepresented social groups and geographical (particularly rural and mountainous) regions through the operation of a complex quota system (Shamatov 2012). On the other hand, it reinforces and produces vertical differentiation and inequalities within the system as students’ academic performance is influenced by existing inequalities in language instruction, educational resources, type of school (public or private), and geographical opportunities (Tiuliundieva 2008). Elite students still have a better chance of winning a state scholarship for the program and university of their choice. This introduces a new form of hierarchy into the HE system as ‘top choice’ universities recruit more students with better scores and which, as they increase their prestige and ‘value’, are able to charge higher tuition fees for fee-paying students as well (DeYoung 2011, 13). Universities are therefore situated within a competitive market in which all strive to recruit state-funded students with high admission test scores, as the more students they recruit the more resources they will accumulate for improving facilities, hiring strong academics, and investing in research. Yet as state tuition grants are minimal and often do not cover the full costs of students’ education, even state scholarships introduce an element of competition between institutions which all angle for economic survival amidst a “radical transformation of the whole market for higher education with the introduction of so-called kontraktnyie, or fee paying places” (Reeves 2005, 15). The introduction and reorientation of higher education financing toward private tuition fees is thus a major driver of both diversification and standardization in Kyrgyzstan today.

Commodification and Marketization: The Influence of Competition on Student Enrollments

Although 86% of students in Kyrgyzstan attend public HEIs, the majority still pay tuition fees as the government provides scholarships for only 21% of full-time students (NSC 2014a) in particular disciplines. As the demand for student-financed education has steadily increased, HEIs have sought new ‘revenue streams’ to attract fee-paying students with concerns that the emphasis on increasing fee-based revenues sometimes supersedes attention to the academic quality of the courses being taught. Various study formats—full-time, part-time, and evening classes—attract different types of students (Fig. 9.5) and international students who often pay more unless they benefit from a bilateral agreement between countries co-sponsoring a university.

Part-time and full-time, day, and evening-class students (Source: Authors using data from NSC 2014a)

This form of educational commodification has been intensified as universities seek new means of financial survival in the absence of adequate state funding (Morgan et al. 2004). In contrast to the internally differentiated Soviet system of universities in which each institution served a particular function in relation to the others, many HEIs now thus offer a range of similar programs with minor modifications. For example, new disciplines which are associated with (or presumed to be associated with) market economics quickly gained prestige after independence, with economics, management, law, international relations, psychology, and foreign languages becoming oversubscribed as students and their families believed these professional qualifications would be lucrative; at the same time, HEIs have struggled to recruit and retain students for technical or teaching courses despite the allocation of state scholarships in such fields (Fig. 9.6).

This has created a problem of saturation in particular fields of study, in which universities educate more specialists than can be employed in a field and lead students to select courses of study instrumentally. By 2015, the state had already closed 23 university branches because they were deemed to be systemic ‘duplications’ (Bengard 2015). While the expansion of educational programs after independence was initially a process of diversification, in other words, the unfolding of this process within a commercialized and marketized environment created a high degree of homogeneity across the system.

The Higher Education Landscape in Contemporary Kyrgyzstan

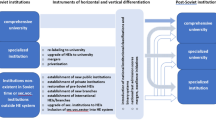

After independence, new legal and policy frameworks for university governance, financing, staffing, and educational programming created conditions for complicated new patterns of differentiation, diversification, and homogenization among higher education institutions in Kyrgyzstan.

The system of higher education now consists of 52 public and private HEIs under the MoES: 3 technical and technological (‘specialized’, or ‘profiled’) universities under the MoES; 1 medical university and 4 medical and healthcare institutes as branches of 2 public and 2 private HEIs, under the Ministry of Health; 1 agrarian institution, under the Ministry of Agriculture; 3 institutions in Arts and Culture, under the Ministry of Culture; 2 institutions in ‘state security’, under the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of the Interior Affairs, and the Ministry of Emergency Situations; 1 university in Sports and Tourism, under the State Agency for Youth, Physical Culture and Sports of the Kyrgyz Republic; 1 diplomatic academy and international relationship academy, under the Ministries of the Interior and Foreign Affairs; 1 Academy of Management, with the President’s Administration; and 1 institute for social work and development, under the Ministry of Labour, Migration and Youth (Table 9.4, Fig. 9.7).

Figure 9.7 represents the current landscape of HEIs in Kyrgyzstan, illustrating each element of external and internal change which has been discussed previously in this chapter. This new landscape includes both historical and newly established public and private universities as well as HEIs which have been created by transforming technical institutes into universities. It also includes a number of institutions with new ‘joint’ forms of governance, such as those which are regulated by both the Kyrgyz Ministry of Education and Science and other government ministries, and joint-national universities such as the Kyrgyz–Russian (Slavic) and Kyrgyz–Turkish Manas universities. The two oldest universities in Kyrgyzstan are the largest, having had many years to build their material and academic infrastructure. Leading specialized public HEIs that have been working since the Soviet period have also had more opportunities and resources (such as space, staff, and students) and some of them changed their statuses to develop in comparison with newly emerged private institutions, and after the collapse of the Soviet Union, these institutions used their advantages to become leading HEIs in their areas of specialization. Private HEIs are comparatively small and still need buildings and finance to operate. Regional HEIs, with the exception of the state universities (e.g., in Issyk Kul and Djalal-Abad), have developed from what were vocational institutions in regional branches of state HEIs and asserted their independence when education was redefined as a profit-making service in order to recruit local students. Leading comprehensive international universities work under bilateral agreements and are mainly funded by foreign countries. These universities build the landscape of HEIs in Kyrgyzstan.

Conclusion

For 25 years, higher education institutions in independent, post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan have undergone rapid, complex changes which are shaped by wider national and global projects to overhaul the social functions, financing, organizational structure, and intellectual content of higher education itself. The 1992 law ‘On Education’ was particularly influential in that it encouraged the creation or annexation of new public and private institutions, including ‘international’ or joint-governmental universities, which are neither dedicated to specific political and economic functions as in the Soviet system nor reliant on state funding for their survival. Yet the expansion of the system from 12 to 52 HEIs (at the time of writing) has not implied an immediate or totalizing diversification of institutional forms. For example, many of the country’s original universities and institutes are still operating today (even if in altered form and under different names), and both Soviet and Bologna degree structures remain in operation across the sector. The development of higher education in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan, while a process of expansion and diversification, remains located within historical and emergent hierarchies which separate older from newer, central from regional, public from private, generalized from specialized, larger from smaller, richer from poorer, and (increasingly) internationally connected from regionally oriented institutions.

These processes have been driven by economic, political and cultural reform agendas which seek to shift from state to private funding for higher education; to create economic and political mechanisms of competition for students, resources, and prestige; and to transform higher education from a public system into a field of autonomous entities which compete for revenue and prestige through the sale of commodified teaching and research products, goods, or services (Amsler 2008, 2013). Within this framework, the Kyrgyz Ministry of Education and Science officially regulates the functions of individual HEIs through its licensing and accreditation mechanisms (although deregulation of ‘attestation’ has been proposed; see Merrill 2016) and maintains control over some processes of institutional diversification such as the functional and hierarchical distinction between elite (PhD-awarding, state-scholarship recruiting) and non-elite (BA-awarding, ‘contract’-focused) institutions. At the same time, externally inspired reforms such as the US-led institutionalization of the National Scholarship Test and the government’s ambition to participate in the European Bologna Process framework have introduced new forces of systemic homogeneity and convergence, largely by introducing and harmonizing mechanisms for ‘quality control’ in HEIs and through this also producing new distinctions (e.g., between HEIs which are more or less compliant, connected to European projects, etc.). As elsewhere in the world, HEIs in Kyrgyzstan are poised between “differentiation and compliance” in the “search for legitimacy” that will “make themselves different to elude competition” (Fumasoli and Huisman 2013, 160).

Yet for individual institutions, within this general context, differentiation, diversification, and market-led specialization are primarily a strategy for survival. As the public budget for higher education has been reduced and HEIs are forced to recruit greater numbers of fee-paying students in order to survive and thrive, they are under pressure to diversify and commodify the form and substance of their activities often regardless of whether such quantitative expansion enhances or damages the quality of educational activities and relationships. In this sense, they follow a familiar cross-national pattern in which universities are “compelled…to start positioning themselves, by constructing portfolios through setting priorities and a more explicit focus on specific competencies” (Fumasoli and Huisman 2013, 157, ADB 2004). However, as illustrated by the ballooning of student applications for and programs dedicated to ‘market-oriented disciplines’ promising (often elusive) individual return and the simultaneous difficulty of recruiting and retaining students to government scholarship-funded programs in core fields such as teacher training, this process in Kyrgyzstan may be more akin to “traditional positioning in for-profit sectors” (ibid., 160; Amsler 2011). In a competitive context where the most marketable niche to occupy is the capacity to occupy a range of marketable niches, the institutions with the greatest resources to do so—accumulated historically, by association with governmental and international power, or through reputation and prestige—have the most capacity for differentiating themselves strategically. This, in addition to the traditional forces of state and market, may have a significant impact on the further development of Kyrgyzstan’s higher education landscape for the foreseeable future.

Notes

- 1.

In 1991, the population was 4,422,000; in 2001, 4,968,119; in 2011, 5,551,888; and in 2015, 5,960,000. The ethnic composition of the population in 2013 was 72% Kyrgyz, 14.4% Uzbek, 6.5% Russian, and 7.1% others (Tajik, Kazakh, Ukrainian, Tatar, Korean, and German) (NSC 2013a, 2014a). Kyrgyzstan is, by World Bank classification, a ‘lower-middle-income’ country with 3.5% annual growth in 2015 (NSC 2015; World Bank 2016). The country’s GDP is heavily dependent on agriculture; mineral resources such as gold, mercury, uranium, and electricity export; and migrants’ remittances working in Russia, Kazakhstan, and other CIS countries. With a Gross Domestic Product of $6.57bn, Kyrgyzstan relies on official development aid, revenues from exporting mineral resources, and migrant labourers’ remittances from work in Russia and other CIS countries.

- 2.

Data for the Frunze special secondary school and Osh Technical University was not available.

- 3.

Key legislation and policy include the Law On Education (1992) and its amendments in 1997, 2003, 2008, etc.; the creation of the ‘Bilim’ National Education Program (1996); the introduction of State Educational Professional Standards in Education (2000); the adoption of the ‘Education for All’ goals of the Dakar Agreement (2001); constitutional revisions (2003); the Development Strategy for Higher and Professional Education of the Kyrgyz Republic (2003); and National Education Strategies, 2007–2010 (2006) and 2012–20 (2012).

References

Amsler, S. 2007. The Politics of Knowledge in Central Asia: Science Between Marx and the Market. London: Routledge.

———. 2008. Higher Education Reform in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan: The Politics of Neoliberal Agendas in Theory and Practice. In Structure and Agency in the Neoliberal University, ed. J. Canaan and W. Shumar. London: Routledge.

———. 2013. The Politics of Privatisation: Insights from the Central Asian University. In Educators, Professionalism and Politics: Global Transitions, National Spaces and Professional Projects, Routledge World Yearbook 2013, ed. T. Seddon and J. Levin. London: Routledge.

Asian Development Bank. 2004. Education Reforms in Countries in Transition: Policies and Processes. Six Country Case Studies Commissioned by the Asian Development Bank in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. http://www.pitt.edu/~weidman/2004-educ-reforms-countries.pdf. Accessed 16 Aug 2016.

Bengard, A. 2015. Kyrgyzstan pri VUZax zakryli 23 instituta [Universities in Kyrgyzstan Close 23 Institutes], 31 July 2015. http://24.kg/obschestvo/17092_v_kyirgyizstane_pri_vuzah_zakryili_23_instituta/. Accessed 21 Aug 2016.

Brunner, J.J., and A. Tillett. 2007. Higher Education in Central Asia: The Challenges of Modernization. In Case Studies from Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Uzbekistan. Washington, DC: World Bank and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Buyanin, Y. 2001. The Kyrgyz of Naryn in the Early Soviet period: A Study Examining Settlement, Collectivisation and dekulakisation on the Basis of Oral History Evidence. Inner Asia 13 (2): 279–296.

Clark, N. 2005. Education Reform in the Former Soviet Union. World Education News and Reviews. http://www.wes.org/eWENR/PF/05dec/pffeature.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2016.

DeYoung, A. 2011. Lost in Transition: Redefining Students and Universities in the Contemporary Kyrgyz Republic. Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing.

Drummond, T., and S. Gabrscek. 2012. Understanding the Higher Education Admissions Reforms in the Eurasian Context. European Education 44 (1): 7–26.

Fumasoli, T., and J. Huisman. 2013. Strategic Agency and System Diversity: Conceptualizing Institutional Positioning in Higher Education. Minerva 51 (2): 155–169.

———. 2011. Decree No. 496 of August 23, 2011 № 496. On the Establishment of a Two-tier Structure of Higher Professional Education in the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek.

———. 2012. Resolution No. 201 of March 23, 2012 on the Strategic Directions for the Development of the Education System in the Kyrgyz Republic. http://cbd.minjust.gov.kg/act/view/ru-ru/92984. Accessed 21 Aug 2016.

Heyneman, S.P. 2010. A Comment on the Changes in Higher Education in the Post-Soviet Union. European Education 42 (1): 76–87.

Holmes, B., G.H. Read, and N. Voskresenskaya. 1995. Russian Education: Tradition and Transition. New York: Garland Publishing.

Huisman, J. 1995. Differentiation, Diversity and Dependency in Higher Education: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Utrecht: Lemma.

Ibraimov, O. 2001. Kyrgyzstan: Encyclopedia. Bishkek: Center of National Language and Encyclopedia Publication.

Khalid, A. 1999. The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform: Jadidism in Central Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Merrill, M.C. 2016. Kyrgyzstan: Quality Assurance – Do State Standards Matter? International Higher Education 85: 27–28.

Mertaugh, M. 2004. Education in Central Asia, with Particular Reference to the Kyrgyz Republic. In The Challenge of Education in Central Asia, ed. S. Heynemann and A.J. DeYoung. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing.

Ministry of Education, Science and Youth Policy of the Kyrgyz Republic. 2006. Education Development Strategy of the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek. Approved by the MoE on 19 October 2006 (order #658/1).

Morgan, A.W., E. Kniazev, and N. Kulikova. 2004. Organizational Adaptation to Resource Decline in Russian Universities. Higher Education Policy 17: 241–256.

Narkoziev, A., and V. Yanzen. 2013. ‘Opyt i perspectivy reformirovania systemy obrazovania v Kyrgyzstane’ [Experiences and Perspectives of the Education System in Kyrgyzstan]. Bishkek: Kyrgyz Russian Slavonic University.

National Statistical Committee. 2008. Education and Science in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2002–2006. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

National Statistical Committee (NSC). 2012a. Education and Science in the Kyrgyz Republic: 2007–2011. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

———. 2012b. Education and Science in the Kyrgyz Republic: 1991–2011. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

———. 2013a. Education and Science in the Kyrgyz Republic. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

———. 2014a. Education and Science in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2009–2013. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

———. 2014b. Socio-economic Position of Kyrgyz Republic. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

———. 2014c. Dynamic Statistics of Students in Educational Institutions. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

———. 2015. Kyrgyz Republic Financial Sector Stability Report. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

———. 2016. Socio-Economic Position of Kyrgyz Republic. Bishkek: National Statistical Committee.

National Tempus Office, Kyrgyzstan. 2016. Higher Education in Kyrgyzstan. Last modified August, 18, 2016. http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/tempus/participating_countries/overview/Kyrgyzstan.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2016.

Orusbaeva, B. et al. 1982. Encyclopedia of Kirgiz Soviet Socialist Republic. Frunze: Glavnaya Redakzia Kirgizskoy Sovetskoy Enziclopedii.

Reeves, M. 2005. Of Credits, kontrakty and Critical Thinking: Encountering “Market Reforms” in Kyrgyzsatni Higher Education. European Education Research Journal 4 (1): 5–21.

Shamatov, D. 2012. Impact of Standardized Tests on University Entrance Issues in Kyrgyzstan. Europe Education 44 (#1): 71–92. (Special volume guest edited by T.W. Drummond and A.J. DeYoung: New Educational Assessment Regimes in Euroasia: Impacts, Issues, and Implications).

———. 2015. Teachers’ Pedagogical Approaches in Kyrgyzstan: Changes and Challenges. In Transforming Teaching and Learning in Asia and the Pacific: Case Studies from Seven Countries, ed. E. Hau-Fai Law and U. Muira, 90–123. Paris: UNESCO.

———. 2011. Education and Postsocialist Transformation in Central Asia – Exploring Margins and Marginalities. In Globalization on the Margins: Education and Postsocialist Transformations in Central Asia, ed. I. Silova. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Teichler, U. 1988. Changing Patterns of the Higher Education System. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Tiuliundieva, N. 2008. The Financing of Higher Education in Kyrgyzstan. Russian Education & Society 50 (1): 75–88.

Van Vught, F. 2008. Mission Diversity and Reputation in Higher Education. Higher Education Policy 21 (2): 151–174.

World Bank. 2016. Kyrgyz Republic. http://data.worldbank.org/country/kyrgyz-republic. Accessed 25 Aug 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shadymanova, J., Amsler, S. (2018). Institutional Strategies of Higher Education Reform in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan: Differentiating to Survive Between State and Market. In: Huisman, J., Smolentseva, A., Froumin, I. (eds) 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries. Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-52979-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-52980-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)