Abstract

Tunisia’s improvements in monetary poverty have not translated into substantive reductions in disparities and unequal opportunities across individuals and regions. Poverty incidence declined from 35% in 2000 to 15% in 2010 (INS, BAD, and World Bank in Mesure de la pauvreté, des inégalités et de la polarisation en Tunisie 2000–2010, 2012). Rapid growth rates and generous universal subsidies, especially on energy, food, and transport, contributed to that successful poverty reduction, but did not have a similar effect on reducing inequalities.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

IMF (2014) analyzes 25 reforms of fuel and food subsidies in 15 countries across five continents between 1983 and 2012.

- 2.

The increasing effect on household consumption reflects the loss of production among noncompetitive sectors of the economy that lose energy subsidies. See World Bank (2013) for a more detailed explanation.

- 3.

The price structure described here became effective on May 1, 2014. The previous tariff structure, valid between January and April 2014, had slightly lower fees for the highest consumption block of the first tier, as well as for the second tier of residential consumption. Appendix 1 details the previous structure.

- 4.

This type of cylinder is typically used by households. Larger cylinders of 25–35 kg are most frequently consumed in the hospitality/tourism industry.

- 5.

From a public finance perspective, the latest data available for both residential and nonresidential consumers in 2013 indicate that some 51% of total energy subsidies go to finance electricity subsidies; 23% to diesel; 15% to LPG; 6% to gasoline; 5% to crude oil; and 1% to kerosene (World Bank 2013).

- 6.

Nevertheless, LPG prices have remained unchanged since February 2010.

- 7.

In addition, the consumption of each energy source and, therefore, the ultimate beneficiaries of the subsidized prices vary substantially by sector, as shown in Appendix 3. Figures reported in Appendix 3 refer to 2012, the latest available for the composition of consumption within each sector, residential and nonresidential.

- 8.

Due to limits on space, the full set of results is not presented here, but is available from the authors upon request.

- 9.

The monetary cost of the food basket defines the extreme poverty line. This line is also adjusted by differences in cost of living for cities (grandes villes), medium-sized towns (petites communes), and rural areas (zones non-communales). The extreme poverty line based on food needs is further adjusted by adding the average spending of extreme poor households on nonfood items to come up with a “low” poverty line and by adding the average spending of nonextreme poor households on nonfood items for setting the “high” poverty line. This exercise uses the upper poverty lines. INS, BAD, and World Bank (2012) provides a detailed description of the construction of the total consumption aggregate.

- 10.

In effect, the three percentage point reduction in the Gini coefficient in simulation 3 implies an 8% reduction in the postreform Gini. The reductions in Gini from the other two simulations render even smaller relative improvements.

References

Araar, A., and P. Verme. 2012. Reforming subsidies: A tool-kit for policy simulations. Middle East and North Africa Region, Policy Research Working Paper 6148, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Government of Tunisia. 2014. Reforme des subventions et du système d’assistance sociale; Organisation et Rôle des Groupes de Travail.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2014. Subsidy reform in the Middle East and North Africa: Recent progress and challenges ahead. Washington, DC: Middle East and Central Asia Department, IMF.

INS (Institut National de la Statistique), BAD (Banque Africaine de Développement), and World Bank. 2012. Mesure de la pauvreté, des inégalités et de la polarisation en Tunisie 2000–2010. Tunis, l’Institut National de la Statistique.

Jomaa, M. 2014. Personne n’a le droit de bloquer les permis pétroliers. Kapitalis, September 4, http://www.kapitalis.com/kapital/24453-mehdi-jomaa-personne-n-a-le-droit-de-bloquer-les-permis-petroliers.html.

Société Tunisienne d’Electricité et du Gaz. 2014. Tables des Tarifs. Direction des Etudes et de la Planification.

World Bank. 2013. Vers une meilleure equité: Les subventions energetiques, le ciblage, et la protection sociales en Tunisie. Washington, DC: Policy Note.

World Bank. 2014. The unfinished revolution: Bringing opportunity, good jobs, and greater wealth to all Tunisians. Washington, DC: Development Policy Review, World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1: Electricity Tariff Structure for Low-Tension Residential Consumers (January 1, 2014)

Fee | Voltage (millimes/kVa/month) | Price of energy by monthly consumption bracket (millimes/kWh) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1–50 | 51–100 | 101–200 | 201–300 | 301–500 | 501+ | ||

Economic (1 and 2 kVa and consumption under 200 kWh) | 500 | 75 | |||||

108 | |||||||

123 | |||||||

Economic (1 and 2 kVa and consumption under 200 kWh); normal (>2 kVa) | 500 | 136 | 157 | 240 | 330 | ||

210 | 270 | ||||||

Appendix 2: Distribution of Monthly Electricity Consumption by Quintile

Consumer <200 kWh per month | Monthly consumption 1–50 kWh | Monthly consumption 51–100 kWh | Monthly consumption 101–200 kWh | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |

Percent by quintile | 48.1 | 19.2 | 12.9 | 11.6 | 8.2 | 32 | 25.5 | 20.1 | 13.7 | 8.7 | 15.9 | 20.5 | 23.2 | 22.6 | 17.9 |

Consumer >200 kWh per month | Monthly consumption 1–300 kWh | Monthly consumption 301–500 kWh | Monthly consumption +501 kWh | ||||||||||||

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |

Percent by quintile | 6.7 | 15.2 | 17.8 | 25.9 | 34.4 | 4.4 | 12.1 | 15.2 | 22.1 | 46.2 | 2.8 | 9.1 | 9.3 | 19.4 | 59.4 |

Appendix 3: Composition of Consumption of Energy Sources by Sector (2012)

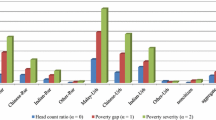

See Fig. 4.6

Composition of consumption of energy sources by sector in 2012. Source World Bank (2013) with data from the International Energy Agency (2012). Note For nonresidential sectors, consumption of energy is an input for their production. For households, it is purely consumption

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cuesta, J., El Lahga, AR., Lara Ibarra, G. (2017). The Socioeconomic Impacts of Energy Reform in Tunisia: A Simulation Approach. In: Verme, P., Araar, A. (eds) The Quest for Subsidy Reforms in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Natural Resource Management and Policy, vol 42. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52926-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52926-4_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-52925-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-52926-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)