Abstract

Since forever colleges and universities compete with each other for students, teachers, donors and social support. For a long time, the competition has been evaluated by implicit reputation without any data to back up perceptions. Recently the competition has been accelerated in many countries as governments develop initiatives to build world-class universities that can compete more effectively with other leading institutions across the globe. Although there are concerns with using rankings as tool for measuring the quality of a university, many institutional leaders still often rely on rankings to inform their policymaking. Global rankings have major impacts on higher education systems, higher education institutions, academics and consumers (students, parents, employers). For this reason, university rankings should encourage universities around the world to carry out a self assessment in relation to several quality issues, including sustainability. None of the main global rankings have so far addressed the issue, both in terms of good practice assessments and as an important signal to society as a whole. The introduction of sustainability in global rankings could be an important addition to the existing metrics and a significant dimension of comparison with multiple and far reaching benefits, not only for single universities as well as for the entire higher educational system. It is important introducing sustainability in global rankings not simply as a criterion for identifying the best universities, but as a general underlying best practice principle in university activities, in the same way they have been recognized in all other institutions such as companies and households.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Since forever colleges and universities have competed with each other for students, teachers, donors and social support. For a long time, the competition has been evaluated by implicit reputation without any data to back up perceptions.

With the heightened competition between universities since the 1990s and the dramatic growth of the international higher education market, survey have emerged in many country as a means of evaluating and ranking universities (Shin and Toutkoushian 2011).

Recently, the competition has been accelerated in many countries as governments develop initiatives to build world-class universities that can compete more effectively with other leading institutions across the globe. Although there are concerns with using rankings as tools for measuring the quality of a university, many institutional leaders and policymakers still often rely on rankings to inform their policymaking.

Global rankings have major impacts on higher education systems, higher education institutions, academics and consumers (students, parents, employers).

For this reason, university rankings should encourage universities around the world to carry out a self-assessment in relation to several quality issues, including sustainability (Hazelkorn 2011). None of the main global rankings have so far addressed the issue, both in terms of good practice assessments and as an important signal to society as a whole.

The introduction of sustainability in global rankings could be an important addition to the existing metrics and a significant dimension of comparison with multiple and far reaching benefits, not only for single universities, but for the entire higher educational system as well.

It is important to introduce sustainability in global rankings not simply as a criterion for identifying the best universities, but as a general underlying best practice principle in university activities, in the same way they have been recognized in all other institutions, such as companies and households.

2 Suggestions from RIO+20

Beginning in 2012, within the RIO+20 initiative (http://goo.gl/NOGOOW), HEIs around the world—with support from UN Academic Impact, UNEP, UNESCO, UN Global Compact, UN-PRME and the UNU—committed to achieving the following important goals:

-

1.

Teach sustainable development concepts, ensuring that they form a part of the core curriculum across all disciplines;

-

2.

Encourage research on sustainable development issues to improve scientific understanding through exchanges of scientific and technological knowledge;

-

3.

Make their campuses greener by:

-

I.

reducing their environmental footprint;

-

II.

adopting sustainable procurement practices;

-

III.

providing sustainable mobility options for students and faculty;

-

IV.

adopting effective programmes for waste minimization, recycling and reuse;

-

V.

encouraging more sustainable lifestyles.

-

I.

-

4.

Support sustainability efforts in the communities where they reside (United Nations 2012b).

Whereas paragraph 243 of the UN resolution following Rio+20 quotes: “We resolve to promote education for sustainable development and to integrate sustainable development more actively into education beyond the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. We strongly encourage educational institutions to consider adopting good practices in sustainability management on their campuses and in their communities with the active participation of, inter alia, students, teachers and local partners, and teaching sustainable development as an integrated component across disciplines.” (United Nations 2012a).

In this paragraph the UN remarks that sustainability is not something people should adopt once in a while, but rather something we must integrate, not only into our organizations or our campuses, but also within our teaching, our studies and our research.

Sustainability is indeed a multifaceted issue including social, environmental, cultural and economical issues (UNESCO 2002).

3 The Potential of Rankings

Global rankings can lead to changes in the academic culture of institutions, and ranking systems can play a big role in the setting and sharing of best practices among organizations, but not only.

Through international rankings we have the opportunity to create awareness and a prominent mean of circulating knowledge that is promoted/encouraged in universities. It is not the only way, but certainly it can be expected to have a significant influence.

Rankings have several positive features and effects: for example they contribute to transparency which is called for because one assumes that many stakeholders yearn for good information and are in need of good information systems in order to be rational actors.

Rankings are also information systems serving the idea that the best achievers will be rewarded, and further they reinforce virtuous, healthy competition; the information on rankings has an overall stimulating effect of increasing efforts to improve (Shin and Toutkoushian 2011).

Rankings should be able to stimulate people into adopting good practices, not only in terms of research and teaching, but also in terms of the way in which they run HEIs. This, in turn, would also help in improving ranking methodological approaches.

Often critics mainly emphasize the methodological weakness of rankings, which are unavoidable limitations of indicators or could be redressed by future improvements.

This paper has the aim to answer to two main questions:

-

1.

Which is the purpose of university rankings?

-

2.

What about the measures used?

For answering the first question we need to discover the main scope of this important tool and understand its real role.

Therefore, it is important to analyze if rankings are used as internal or external tools because this entails various consequences.

If rankings are used as an internal tool, it will serve to set the objectives of improving the organization and to plan the future activities.

If rankings are used as an external tool this may serve to three purposes:

-

(a)

to allocate resources/attract enrollments both at national and international level

-

(b)

to push the competitors/other academies to follow best practices both on a general and single entity’s level;

-

(c)

to account for the resources given on a single entity’s level. It must be considered not only the funds, but also those resources presented in the balance sheet of other entities or externalities (such as the transports and landscape).

Rankings have an important role in determining the reputation, and at the same time the reputation of an organization has a greater weight in rankings. Reputation is an intangible asset, hard to construct and, if lost, hard to recover. The empirical evidence on the subject indicates that organizations, including universities, are right to worry about their reputation and its attached benefits. The difficulty in higher education is that reputation is a resource that cannot be easily purchased or improved.

The reputation of institution as gained in the marketplace has always functioned partly in the US academic marketplace, but now it is broadly functioning across the world. As a result, ranking has increased its visibility and impact (Shin and Toutkoushian 2011).

Often, it is assumed that highly ranked institutions are more productive, have higher quality teaching and research and contribute more to society than lower-ranked institutions. However, the three main dimensions of institutions—teaching, research and service—can differ or even conflict with each other, and those institutions that are performing well in one area may perform poorly along another dimension.

We should also wonder if ranking measures are related to measures of quality or organizational effectiveness. When considering ranking as a way of measuring institutional effectiveness or performance, it should reflect dimensions of organizational effective or quality (Hazelkorn 2011).

We must pay attention to ranking and quality management system because these mechanisms contribute to institutional quality and organizational effectiveness. Ranking, however, does not guarantee that institutional quality is enhanced by moving toward a higher rank.

Ranking was designed to lead to competition among academics and to enhance institutional quality: if ranking does not contribute to institutional quality, but simply provides information for college choice, it may lose its legitimacy. But it is possible to affirm that rankings aim to measure the average quality of a higher education institution.

University rankings in general attempt to account for the capability of HEIs to perform and grant deliverables to their stakeholders: academic and employer reputation, the level of scientific research, the degree of internationalization, these are all proxies of the quality of the product that a university is able to deliver. Accountability refers to rendering an account about what an institution is doing in relation to goals that have been set, or legitimate expectations that others may have of one’s services or processes, in terms that can be understood by those who have a need or right to understand the account.

However, there is still a clear gap between the picture provided by university rankings and a complete description of everyday life in the university community. At best, present university rankings can only provide a rather limited and partial view of the reality, whereas there is an increasing awareness of the fact that rankings could reflect—and indeed they should reflect—different behaviours of universities, and in particular the different ability among universities to comply and to cope with sustainability issues.

This discrepancy originates from a twofold aspect: on the one hand, rankings use a necessarily limited set of indicators to evaluate multi-output organizations, as universities are not enterprises; on the other hand, particularly in Europe, university is a right, not just an opportunity. HEIs are therefore complex organizations, and rankings measure only what is measurable, and not only what matters.

In this perspective, we should not underestimate the fact that higher education systems should be increasingly more accountable to their stakeholders, who have a growing importance, both in the EU, as well as in the rest of the World.

The second question suggests analyzing measures and indicators used in ranking systems.

Given that “what you measure is what you get”, the measurements cannot be limited only to what is easier to measure. Activities and countable phenomena are by sure easy to manage, but HEI should focus on education, which is definitely more difficult to capture (Mio 2013).

It is most important to understand how to measure the higher education and which are the more suitable indicators to this purpose, even if one should proceed by proxy.

The first point to assess is that it does not exist an absolute measure applicable to all organizations, but it is necessary to consider the context in which the university operates. For instance, the economic situation and the development rate of a country or region must be considered in the planning of a measurement system, particularly when measuring social impacts.

Ranking universities have a challenging task because each institution has its own particular mission, focus and can offer different academic programs. Institutions can also differ in size and have varying amounts of resources at their disposal.

Another important issue for university rankings is how to take into account the disciplinary differences across institutions. Some are more oriented toward the hard science, whereas others are more focused on liberal arts. Disciplines can differ in paradigms, preferred publication types, preferred research types (pure vs. applied), research methodology, time allocation between different types of academic activities.

In addition, each country has its own history and higher education system which can impact the structure of their colleges and universities and how they compare to others. It is very difficult to rank properly entire universities, especially across national borders, according to the single criterion of ranking indicators.

The next step is to develop a set of indicators appropriate to measure the higher education. To do this, it could be useful to see which are those already used in the on-going evaluation process of education system (elementary school, middle school and high school).

An important methodological issue for rating agencies concerns the proper weightings of indicators in overall rankings of institutions. Some indicators are typically weighted more highly than others. The ambiguity of weights also leads to the development of new rankings which use different sets of indicators and weights.

For sure, the measurement system cannot be left to the market, because it could lead to misleading results. The enrol price is not equivalent to the value of outcome generated by an HEI.

Giving that the current university rankings represent a partial picture of what a university is and what a university does, it would not be hard to conceive the inclusion of an additional semi-quantitative set of indicators reflecting the sensibility of a university system toward the sustainability framework. Therefore, the real issue is not if sustainability indicators could be included in university rankings, but rather why they should be included. Several possible reasons can be mentioned here.

Firstly, ranking methodologies are not immutable and have been changed over the years to reflect a rapidly changing academic and research world, as already remarked. These methodological changes have always been favourably welcomed both by students and university decision makers, as a way to provide a more realistic representation of the university system. In no known cases, these modifications have jeopardized the original strengths of the ranking and in fact they have often addressed some of their weaknesses (Rauhvargers 2011, 2013). Referring to this consideration, rankings should account that the most important universities in the world have already decided to take part in the big challenge of changing the world for the future generation. Indeed, an increasingly number of universities are committing to developing and maintaining an environment that enhances human health and fosters a transition toward sustainability.

Secondly, whether we like it or not, university rankings are not simply a measure of existing performances, but they have a significant impact on public opinion and decision makers. As a proxy for quality, therefore, they should strive to be as comprehensive and objective as possible.

Last but not least, we all hope for a better world for future generations, and a good university system is definitely a building block for that. University needs to be visionary centres of sustainability, innovation and excellence and to promulgate values and health of society.

In the recent years, there have been developed some rankings specialized in the accounting of the environmental impact of universities.

One of the most famous examples is the UI GreenMetric—World University Ranking.

This is one of the main university rankings specialized in the rating of world universities from a “green” perspective. Universitas Indonesia developed this ranking in the 2010 and was first based on information provided by universities around the world on criteria that demonstrate commitment to going green and sustainable, such as space, energy efficiency, water use, and transport and so on.

Thanks to the feedback, comments and suggestions received from the participants, this ranking has been improved from then and it is now addressed to measure how much the universities are committed to reduce their impact on the environment, and to help promote awareness of the importance of sustainability.

GreenMetric analyses six areas: setting and infrastructure, energy and climate change, waste, water, transportation, education.

Right from the beginning this ranking showed its limits.

The first problem that the GreenMetric team had to face was the differences due to the variety of contexts wherein universities are placed.

Indeed, considering some indicators, universities located in city centre or in historical cities could be disadvantaged because they have not a lot of leeway in making actions to reduce their environmental impacts through building works or enlarging green spaces. For instance, in some historical cities there are no possibilities to build new and green buildings or to install solar panels, because making this kind of interventions involves important structural works in buildings that are often protected by artistic restrictions.

Moreover, environmental impacts can be very different from a climate zone to another and this influences considerably the amount of KWH used. A similar consideration can be made also for the indicator “percentage of area covered in vegetation”, that in some countries is inevitably bigger than other countries with a high population density per square kilometre, or even the presence of a forest inside the campus.

Another big limit of GreenMetric ranking is the lack of the social dimension of sustainability: there is no indicator that measures the social impacts of universities and social cohesion, although this dimension produces probably the most relevant and evident results for a community, also in the economic sphere.

4 Conclusion

It is possible to assert without a doubt that sustainability can be a criterion to measure the quality of a university. This explains why the introduction of sustainability in global rankings could be an important addition to the existing metrics and an important dimension of comparison.

The integration of sustainability in standard ranking certainly brings multiple benefits, not only for single universities, but at the same time for the entire higher educational system.

For introducing sustainability in global rankings, it is important to consider it not simply as a criterion for identifying the best universities, but as a general underlying best practice principle in university activities.

Therefore, it is fundamental to promote the integration of sustainability indicators into standard university rankings, not only for the assessment, but also for spreading a sustainable perspective into all academic institutions, and to do this we must involve key players of rating system and of sustainability processes (Mio 2013).

This mechanism would stimulate the participation of all universities and not only of those already committed in sustainability.

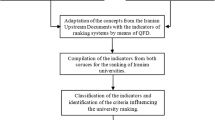

From an operative point of view, if the intention is to develop a ranking for measuring the commitment to sustainability of universities and taking into account all these considerations, there are two ways:

-

developing indicators considering the different possible contexts;

-

developing a set of indicators applicable for every context.

In the first case, it should be provided a great variety of indicators that deeply analyze different aspects with a high level of detail. This method implicates that the data collection may be more problematic for many institutions—that normally do not produce these kinds of data—and this would compromise the aim for spreading sustainable practices.

The second way suggests the developing of a limited set of indicators applicable for most of the institutions and this could be the right way of favouring the participation.

In this case, the indicators must give a right representation of the university commitment in sustainability, analyzing for example the weight of the research and teaching on sustainable topics and how much the management of sustainability is integrated in the processes of an organization.

Indeed, for considering a university as sustainable, this should not only have research and teaching on sustainable topics, but it must be sustainable itself, involving the whole organization and all processes.

References

Hazelkorn, E. (2011). Rankings and the reshaping of higher education. London: Palgrave and MacMillan.

Mio, C. (2013). Towards a sustainable university—The Ca’ Foscari experience. London: Palgrave and MacMillan.

Rauhvargers, A. (2011). Global university rankings and their impact I, EUA report on ranking 2011.

Rauhvargers, A. (2013). Global university rankings and their impact II, EUA report on ranking 2013.

Shin, J. C., Toutkoushian, R. K. (2011). The past, present, and future of university rankings. In University rankings. Theoretical basis, methodology and impacts on global higher education. New York: Springer.

United Nations. (2012a). Report of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. http://www.uncsd2012.org/content/documents/814UNCSD%20REPORT%20final%20revs.pdf

United Nations. (2012b). A practical guide to the United Nations global compact for higher education institutions: Implementing the global compact principles and communicating on progress. http://www.unprme.org/resource-docs/ApracticalGuidetotheUnitedNationsGlobalCompactforHigherEducationInstitutions.pdf

UNESCO. (2002). Education for sustainability—From Rio to Johannesburg: Lessons learnt from a decade of commitment. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001271/127100e.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Copyright information

© 2015 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Porzionato, M., De Marco, F. (2015). Excellence and Diversification of Higher Education Institutions’ Missions. In: Curaj, A., Matei, L., Pricopie, R., Salmi, J., Scott, P. (eds) The European Higher Education Area. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_19

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-18767-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20877-0

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)