Abstract

Despite the centrality of kin concepts in the development of much anthropological theory, Paleoindian colonization is often simplistically modeled as biological population fissioning or with unwarranted assumptions about social organization and demographic parameters. Yet, Paleoindian people were undoubtedly aware of critical options for managing the sociogeographic boundary at which marriages could occur where small group sizes and extremely low population densities prevailed. Plausible thought models for a common category of kin structures that could have entered the New World can be developed quite readily. These models allow meaningful inferences about Paleoindian kinship, with profound implications for our understanding of the earliest stages of New World prehistory, both at regional and continental scales. Such models can serve to stimulate alternative explanations with test implications for enigmatic aspects of the Paleoindian record, including differential demographic success for colonization episodes, shifting modes of colonization, the kin-structuring of economic options, and social dimensions signaled by the spread of fluted point technology.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Figure 10.1 is a considerable simplification arising from Dravidian kin semantics, used here for illustrative purposes. It is important to remain aware that the associative rules used to classify more distant relatives (for example, the potential affine mother’s mother’s brother’s daughter’s daughter) can be the subject of elaborate mathematical description (Godelier et al. 1998). This abstract semantic dimension is further complicated by the vagaries of real world genealogical tracings, with multiple pathways even for one individual. In fact, not all members of a society are apt to possess such detailed knowledge. In the world of the Mackenzie Basin Dene, that knowledge lies in the domain of elderly women, who can distinguish real and classificatory siblings from potential marriage partners, for instance (Asch 1998). When Dene women from distant communities meet, it is common to hear them begin tracing out individuals they have in common, and therefore, how they might be related, as part of a vast web of kin ties that can extend over hundreds of kilometers.

- 2.

The painted mammoth skull from Mezerich illustrated by Soffer (1985:78, Fig. 2.73), for example, has a design that curves somewhat, but otherwise has nearly perfect symmetry; almost every design element to the left of the mid-line is mirrored to the right.

- 3.

This is not to say that other modeling scenarios could not be developed for kin systems that are of cognatic character, for instance, calculating degrees of relatedness, rather than absolute categorical prescriptions of affinity and consanguinity as we see in systems reckoning cross-parallel distinctions. The Nadleh Whut’en (southern Carrier), for instance, have a cognatic terminology with marriage rules governed by the Law of Four Sticks, which stipulated that neither siblings nor first, second, or third cousins could marry (McQuary and Poser 1996). I will leave modelling of logical possibilities in these semantic realms to be explored by others more familiar with such kin systems, but observe that the upshot of requiring marriages at four removes or beyond provides for a highly exogamous alternative akin to Local Group Alliance distinctions.

- 4.

Such factors as the chronological length of the fluted point era, modern population densities, degree of cultivation, collecting histories and other key factors can and have acted to bias this fluted point density pattern. Nevertheless, even in dedicated efforts to detect sources of bias concerning this pattern, several authors indicate that there remains an underlying degree of “patchiness” in this distribution that cannot entirely be attributed to biasing factors, and does seem to be a property of the fluted point distribution in North America (e.g., Buchanan 2003; Prasciunas 2011:122).

- 5.

I will use the term “Corridor” sensu lato to refer to regions principally east of the Rockies, where continental ice flowed toward and in some instances coalesced with ice masses of Cordilleran origin during the Late Wisconsinan (Ives et al. 2013). The term “Corridor” has some value in characterizing the long “seam” that expanded as deglaciation proceeded, but the entire scenario was time and space transgressive. As we proceed into post-glacial time, the notion of a corridor becomes less and less helpful, although that broadening zone is of considerable archaeological interest. Mandryk (1992) provided a history of the Corridor concept.

- 6.

Some Chindadn-like and Sluiceway-like points have been found in Alberta, but none in circumstances that can be dated; consequently, there are no assemblages or diagnostics known to be contemporaneous with Clovis but having links to the north. Microblades do occur at various sites throughout the province, and while some of these are mid-Holocene age and younger, some are likely to be relatively ancient (Fedje et al. 1995; Wilson et al. 2011). The Component II Dry Creek materials contain similar microcores along with distinctive, thick, heavily resharpened oblanceolate points or knives. These last artifacts do occur in both northern and southern Alberta, and might speak to a northern presence in the Corridor region as early as ca. 9,800–10,500 14C year bp (Ives 1993). That an even earlier northern presence in the Corridor region is difficult to affirm at the moment should in no way be taken to mean it could not easily be so (cf. Landals 2008).

References

Adovasio, J. M., & Pedler, D. R. (2013). The ones that still won’t go away: More biased thoughts on the pre-Clovis peopling of the New World. In K. E. Graf, C. V. Ketron, & M. R. Waters (Eds.), Paleoamerican odyssey (pp. 511–520). College Station, TX: Center for the Study of the First Americans, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University.

Allen, N. J. (2003). The prehistory of Dravidian-type kin terminologies. In M. Godelier, T. R. Trautmann, & F. E. Tjon Sie Fat (Eds.), Transformations of kinship (pp. 314–341). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Allen, N. J. (2008). Tetradic theory and the origin of human kinship systems. In N. J. Allen, H. Calan, R. Dunbar, & W. James (Eds.), Early human kinship: From sex to social reproduction (pp. 96–112). Oxford, England: Royal Anthropological Institute/Blackwell.

Ammerman, A. J. (1975). Late Pleistocene population dynamics: An alternative view. Human Ecology, 3(4), 219–233.

Anderson, D. G., & Gillam, J. C. (2000). Paleoindian colonization of the Americas: Implications from an examination of physiography, demography, and artifact distribution. American Antiquity, 65(1), 43–66.

Anderson, D. G., & Gillam, J. C. (2001). Paleoindian interaction and mating networks: Reply to Moore and Moseley. American Antiquity, 66(3), 526–529.

Anderson, D. J., Miller, D. S., Yerka, S. J., Gillam, J. C., Johanson, E. N., Anderson, D. T., et al. (2010). PIDBA (Paleoindian Database of the Americas) 2010: Current status and findings. Archaeology of Eastern North America, 38, 63–90.

Anthony, D. W. (1990). Migration in archaeology: The baby and the bathwater. American Anthropologist, 92(4), 895–916.

Anthony, D. W. (1997). Prehistoric migration as social process. In J. Chapman & H. Hamerow (Eds.), Migrations and invasions in archaeological explanation: Vol. 664. BAR International Series (pp. 21–32). Oxford, England: Archaeopress.

Anthony, D. W. (2007). The horse, the wheel and language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Asch, M. I. (1980). Steps toward the analysis of Athapaskan social organization. Arctic Anthropology, 17(2), 46–51.

Asch, M. I. (1988). Kinship and the drum dance in a northern Dene community (The Circumpolar Research Series). Edmonton, AB: The Boreal Institute for Northern Studies and Academic Printing and Publishing.

Asch, M. I. (1998). Kinship and Dravidianate logic: Some implications for understanding power, politics, and social life in a northern Dene community. In M. Godelier, T. R. Trautmann, & F. E. Tjon Sie Fat (Eds.), Transformations of kinship (pp. 140–149). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Bamforth, D. B. (2009). Projectile points, people, and plains Paleoindian perambulations. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 28, 142–157.

Beck, C., & Jones, G. T. (2010). Clovis and western stemmed: Population migration and the meeting of two technologies in the Intermountain West. American Antiquity, 75(1), 81–116.

Benders, Q. (2010). Agate Basin archaeology in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton.

Binford, L. R. (2001). Constructing frames of reference: An analytical method for archaeological theory building using ethnographic and environmental data sets. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bradley, B. A., & Collins, M. B. (2013). Imagining Clovis as a cultural revitalization movement. In K. E. Graf, C. V. Ketron, & M. R. Waters (Eds.), Paleoamerican odyssey (pp. 247–255). College Station, TX: Center for the Study of the First Americans, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University.

Bradley, B. A., Collins, M. B., & Hemmings, A. (2010). Clovis technology: International Monographs in Prehistory: Vol. 17. Archaeological Series. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Brown, C. T., Liebovitch, L. S., & Glendon, R. (2007). Lévy flights in Dobe Ju/’hoansi foraging patterns. Human Ecology, 35, 129–138.

Buchanan, B. (2003). The effects of sample bias on Paleoindian fluted point recovery in the United States. North American Archaeologist, 24(4), 311–338.

Buchanan, B., & Collard, M. (2007). Investigating the peopling of North America through cladistic analyses of early Paleoindian projectile points. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 26, 366–393.

Buchanan, B., & Collard, M. (2008). Phenetics, cladistics, and the search for the Alaskan ancestors of the Paleoindians: A reassessment of relationships among the Clovis, Nenana, and Denali archaeological complexes. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(6), 1683–1694.

Buchanan, B., & Hamilton, M. J. (2009). A formal test of the origin of variation in North American early Paleoindian points. American Antiquity, 74(2), 279–298.

Clayton, L., Bickley, W. B., & Stone, W. J. (1970). Knife river flint. Plains Anthropologist, 15, 282–290.

Collins, M. B., Stanford, D. J., Lowery, D. L., & Bradley, B. A. (2013). North America before Clovis: Variance in temporal/spatial cultural patterns 27,000–13,000 cal yr BP. In K. E. Graf, C. V. Ketron, & M. R. Waters (Eds.), Paleoamerican odyssey (pp. 521–539). College Station, TX: Center for the Study of the First Americans, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University.

Dawe, R. J. (2013). A review of the Cody Complex in Alberta. In E. J. Knell & M. P. Muñiz (Eds.), Paleoindian lifeways of the Cody Complex (pp. 144–187). Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

Dikov, N. N., & Titov, E. E. (1984). Problems of the stratification and periodization of the Ushki sites. Arctic Anthropology, 21(2), 69–80.

Driver, J. C., Handly, M., Fladmark, K. R., Nelson, D. E., Sullivan, G. M., & Preston, R. (1996). Stratigraphy, radiocarbon dating and culture history of Charlie Lake Cave, British Columbia. Arctic, 49(3), 265–277.

Dyke, A. S. (2005). Late Quaternary vegetation history of northern North America based on pollen, macrofossil, and faunal remains. Géographie Physique et Quaternaire, 59(2-3), 211–262.

Eggan, F. (1955a). The Cheyenne and Arapaho kinship system. In F. Eggan (Ed.), Social anthropology of North America tribes (pp. 35–95). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eggan, F. (1955b). Social anthropology: Methods and results. In F. Eggan (Ed.), Social anthropology of North America tribes (pp. 485–551). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ellis, C. (2011). Measuring Paleoindian range mobility and land-use in the Great Lakes/Northeast. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 30, 385–401.

Fedje, D. W., White, J. M., Wilson, M. C., Nelson, D. E., Vogel, J. S., & Southon, J. R. (1995). Vermilion Lakes site: Adaptations and environments in the Canadian Rockies during the latest Pleistocene and early Holocene. American Antiquity, 60(1), 81–108.

Frison, G. C., & Bradley, B. (1999). The Fenn cache: Clovis weapons and tools. Santa Fe, NM: One Horse Land and Cattle Company.

Frison, G. C., & Todd, L. C. (1986). The Colby mammoth site: Taphonomy and archaeology of a Clovis kill in northern Wyoming. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Godelier, M., Trautmann, T. R., & Tjon Sie Fat, F. E. (1998). Transformations of kinship. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Goebel, T., & Buvit, I. (Eds.). (2011). From the Yenisei to the Yukon: Interpreting lithic assemblage variability in late Pleistocene/early Holocene Beringia. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Goebel, T., Smith, H. L., DiPietro, L., Waters, M. R., Hockett, B., Graf, K. E., et al. (2013). Serpentine Hot Springs, Alaska: Results of excavations and implications for the age and significance of northern fluted points. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40, 4222–4233.

Gruhn, R., & Bryan, A. (2011). A current view of the initial peopling of the Americas. In D. Vialou (Ed.), Peuplements et préhistoire en Amériques (pp. 17–30). Paris: Éditions du Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientific.

Gryba, E. M. (2001). Evidence of the fluted point tradition in western Canada. In J. Gillespie, S. Tupakka, & C. de Mille (Eds.), On being first: Cultural innovation and environmental consequences of first peopling: Proceedings of the 31st Annual Chacmool Conference (pp. 251–284). Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Archaeological Association.

Hage, P. (2003). The ancient Maya kinship system. Journal of Anthropological Research, 59(1), 5–21.

Hage, P., Milicic, B., Mixco, M., & Nichols, J. P. (2004). The proto-Numic kinship system. Journal of Anthropological Research, 60(3), 359–377.

Hall, J. B. (2009). Pointing it out: Fluted projectile point distributions and early human populations in Saskatchewan. Unpublished master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver.

Haynes, G. (2002). The early settlement of North America: The Clovis era. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Haynes, C. V., Jr., & Huckell, B. B. (Eds.). (2007). Murray Springs: A Clovis site with multiple activity areas in the San Pedro Valley, Arizona. Tucson, AZ: Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona.

Hazelwood, L., & Steele, J. (2003). Colonizing new landscapes: Archaeological detectability of the first phase. In M. Rockman & J. Steele (Eds.), Colonization of unfamiliar landscapes: The archaeology of adaptation (pp. 203–221). New York: Routledge.

Hill, K. R., Walker, R. S., Božičević, M., Eder, J., Headland, T., Hewlett, B., et al. (2011). Co-residence patterns in hunter-gatherer societies show unique human social structure. Science, 331, 1286–1289.

Hockett, C. F. (1964). The proto Central Algonkian kinship system. In W. H. Goodenough (Ed.), Explorations in cultural anthropology (pp. 239–257). Toronto, ON: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Holen, S. R. (2005). Taphonomy of two last glacial mammoth sites in the central Great Plains of North America: A preliminary report on La Sena and Lovewell. Quaternary International, 142–143, 30–43.

Holly, D. H. (2011). When foragers fail: In the eastern Subarctic, for example. In K. E. Sassaman & D. H. Holly (Eds.), Hunter-gatherer archaeology as historical process (pp. 79–92). Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

Ives, J. W. (1990). A theory of northern Athapaskan prehistory. Boulder, CO/Calgary, AB: Westview Press/University of Calgary Press.

Ives, J. W. (1993). The ten thousand years before the fur trade in northeastern Alberta. In P. A. McCormack & R. G. Ironside (Eds.), The uncovered past: Roots of northern Alberta societies (Circumpolar Research Series No. 3, pp. 5–31). Edmonton, AB: Canadian Circumpolar Institute, University of Alberta.

Ives, J. W. (1998). Developmental processes in the pre-contact history of Athapaskan, Algonquian and Numic kin systems. In Transformations of kinship (pp. 94–139). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Ives, J. W. (2006). 13,001 years ago—Human beginnings in Alberta. In M. Payne, D. Wetherell, & C. Cavanaugh (Eds.), Alberta formed—Alberta transformed (Vol. 1, pp. 1–34). Calgary/Edmonton, AB: University of Calgary/University of Alberta Presses.

Ives, J. W., Froese, D., Collins, M., & Brock, F. (2014). Radiocarbon and protein analyses indicate an early Holocene age for the bone rod from Grenfell, Saskatchewan, Canada. American Antiquity, 79(4), 782–793.

Ives, J. W., Froese, D., Supernant, K., & Yanicki, G. (2013). Vectors, vestiges and Valhallas—Rethinking the corridor. In K. E. Graf, C. V. Ketron, & M. R. Waters (Eds.), Paleoamerican odyssey (pp. 149–169). College Station, TX: Center for the Study of the First Americans, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University.

Ives, J. W., Vajda, E. J., & Rice, S. (2010). Dene-Yeniseian and processes of deep change in kin terminologies. In Anthropological papers of the University of Alaska: Vol. 5. New Series (pp. 223–256).

Johnston, G. (1982). Organizational structure and scalar stress. In C. Renfrew, M. Rowlands, & B. Segrave (Eds.), Theory and explanation in archaeology (pp. 389–421). New York: Academic.

Kehoe, T. F. (1966). The distribution and implications of fluted points in Saskatchewan. American Antiquity, 31(4), 530–539.

Kelly, R. L., & Todd, L. C. (1988). Coming into the country: Early Paleoindian hunting and mobility. American Antiquity, 53(2), 231–244.

Keyser-Tracqui, C., Crubézy, E., & Ludes, B. (2003). Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2,000-year-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia. American Journal of Human Genetics, 73, 247–260.

Klein, R. G. (1973). Ice-age hunters of the Ukraine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Knell, E. J., & Muñiz, M. P. (2013). Introducing the Cody Complex. In E. J. Knell & M. P. Muñiz (Eds.), Paleoindian lifeways of the Cody Complex (pp. 3–28). Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

Kooyman, B., Newman, M. E., Cluney, C., Lobb, M., Tolman, S., MacNeil, P., et al. (2001). Identification of horse exploitation by Clovis hunters based on protein analysis. American Antiquity, 66, 686–691.

Krauss, M. E. (n.d.). The proto-Athapaskan and Eyak kinship term system. Unpublished paper in possession of author. (Original work published 1977)

Lalueza-Fox, C., Rosas, A., Estalrrich, A., Gigli, E., Campos, P. F., García-Tabernero, A., et al. (2011). Genetic evidence for patrilocal mating behavior among Neandertal groups. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(1), 250–253.

Landals, A. J. (2008). The Lake Minnewanka site: Patterns in late Pleistocene use of the Alberta Rocky Mountains. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural anthropology. Boston: Beacon.

Lewis, M. A., & Kareiva, P. (1993). Allee dynamics and the spread of invading organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158.

Lohse, J. C. (2010). Evidence for learning and skill transmission in Clovis blade production and core maintenance. In B. A. Bradley, M. B. Collins, & A. Hemmings (Eds.), Clovis technology: International Monographs in Prehistory: Vol. 17. Archaeological Series (pp. 157–176). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

MacDonald, D. H. (1998). Subsistence, sex, and cultural transmission in Folsom culture. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 17, 217–239.

Mandryk, C. S. (1992). Paleoecology as contextual archaeology: Human viability of the late Quaternary Ice-Free corridor, Alberta, Canada. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, Edmonton.

Mandryk, C. S. (1996). Late Wisconsinan deglaciation of Alberta: Process and palaeogeography. Quaternary International, 32, 79–85.

McQuary, B., & Poser, B. (1996). The Carrier kinship system. Handout from the Athapaskan Language Conference, 1996, University of Alberta, Edmonton.

Means, B. K. (2007). Circular villages of the Monongahela tradition. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Medvedev, G. I. (1998). Art from central Siberian Paleolithic sites. In A. P. Derev’anko, W. R. Powers, & D. B. Shimkin (Eds.), The Paleolithic of Siberia. New discoveries and interpretations (pp. 132–137). Novosibirsk, Russia: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Siberian Division, Russian Academy of Sciences.

Meltzer, D. J. (2002). What do you do when no one’s been there before? Thoughts on the explorations and colonization of new lands. In N. G. Jablonski (Ed.), The First Americans. The Pleistocene colonization of the New World (Vol. 27, pp. 27–58). San Francisco: Memoirs of the California Academy of Science.

Meltzer, D. J. (2009). First peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Meyer, D., Beaudoin, A. B., & Amundson, L. J. (2012). Human ecology of the Canadian Prairie ecozone ca. 9000 BP—The Paleo-Indian period. In B. A. Nicolson (Ed.), Human ecology of the Canadian Prairie Ecozone 11,000 to 300 BP (pp. 5–52). Regina, SK: Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina.

Moore, J. H. (2001). Evaluating five models of human colonization. American Anthropologist, 103(2), 395–408.

Moore, J. H., & Moseley, M. E. (2001). How many frogs does it take to leap around the Americas? Comments on Anderson and Gillam. American Antiquity, 66(3), 526–529.

Morlan, R. E. (2003). Current perspectives on the Pleistocene archaeology of eastern Beringia. Quaternary Research, 60, 123–132.

Morlan, R. E., & Cinq-Mars, J. (1982). Ancient Beringians: Human occupation in the late Pleistocene of Alaska and the Yukon Territory. In D. M. Hopkins, J. V. Matthews, C. E. Schweger, & S. B. Young (Eds.), Paleoecology of Beringia (pp. 353–381). New York: Academic.

Morrow, J. E., & Morrow, T. A. (1999). Geographic variation in fluted projectile points: A hemispheric perspective. American Antiquity, 64(2), 215–230.

Potter, B. A., Holmes, C. E., & Yesner, D. R. (2013). Technology and economy among the earliest prehistoric foragers in interior eastern Beringia. In K. E. Graf, C. V. Ketron, & M. R. Waters (Eds.), Paleoamerican odyssey (pp. 81–103). College Station, TX: Center for the Study of the First Americans, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University.

Potter, B. A., Irish, J. D., Reuther, J. D., Gelvin-Reymiller, C., & Holliday, V. T. (2011). A terminal Pleistocene child cremation and residential structure from eastern Beringia. Science, 331, 1058–1062.

Prasciunas, M. M. (2011). Mapping Clovis: Projectile points, behavior, and bias. American Antiquity, 76, 107–126.

Prüfer, K., Racimo, F., Patterson, N., Jay, F., Sankararaman, S., Sawyer, S., et al. (2013). The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature, 505, 43–49.

Raghavan, M., Skoglund, P., Graf, K. E., Metspalu, M., Albrechtsen, A., Moltke, I., et al. (2014). Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans. Nature, 505, 87–91.

Rasmussen, M., Anzick, S. L., Waters, M. R., Skoglund, P., DeGiorgio, M., Stafford, T. W., Jr., et al. (2014). The genome of a late Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana. Nature, 506, 225–229.

Ridington, R. (1968a). The environmental context of Beaver Indian behavior. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Ridington, R. (1968b). The medicine fight: An instrument of political process among the Beaver Indians. American Anthropologist 70, 1152–1160.

Ridington, R. (1969). Kin categories versus kin groups: A two section system without sections. Ethnology, 8(4), 460–467.

Robinson, B. S., Ort, J. C., Eldridge, W. A., Burke, A. L., & Pelletier, B. G. (2009). Paleoindian aggregation and social context at Bull Brook. American Antiquity, 74(3), 423–447.

Rockman, M., & Steele, J. (Eds.). (2003). Colonization of unfamiliar landscapes: The archaeology of adaptation. New York: Routledge.

Root, M. J., Knell, E. J., & Taylor, J. (2013). Cody Complex land use in western North Dakota and southern Saskatchewan. In E. J. Knell & M. P. Muñiz (Eds.), Paleoindian lifeways of the Cody Complex (pp. 121–143). Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

Seeman, M. F. (1994). Intercluster lithic patterning at Nobles Pond: A case for “disembedded” procurement among early Paleoindian societies. American Antiquity, 59(2), 273–288.

Slobodin, R. (1962). Band organization of the Peel River Kutchin (Bulletin No. 179, Anthropological Series No. 55). Ottawa, ON: National Museum of Canada.

Smallwood, A. (2012). Clovis technology and settlement in the American Southeast: Using biface analysis to evaluate dispersal models. American Antiquity, 77(4), 689–713.

Smith, H. L., Rasic, J. T., & Goebel, T. (2013). Biface traditions of northern Alaska and their role in the peopling of the Americas. In K. E. Graf, C. V. Ketron, & M. R. Waters (Eds.), Paleoamerican odyssey (pp. 105–123). College Station, TX: Center for the Study of the First Americans, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University.

Soffer, O. (1985). The Upper Paleolithic of the central Russian Plain. Orlando, FL: Academic.

Speth, J. D., Newlander, K., White, A. A., Lemke, A. K., & Anderson, L. E. (2013). Early Paleoindian big-game hunting in North America: Provisioning or politics? Quaternary International, 285, 111–139.

Spier, L. (1925). The distribution of kinship systems in North America. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology, 1(2), 69–88.

Stanford, D. J., & Bradley, B. A. (2012). Across the Atlantic. The origins of America’s Clovis culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Steele, J. (2009). Human dispersals: Mathematical models and the archaeological record. Human Biology, 81(2–3), 121–140.

Stevenson, M. (1997). Inuit, whalers, and cultural persistence. Structure in Cumberland Sound and central Inuit social organization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Tamm, E., Kivisild, T., Reidla, M., Metspalu, M., Smith, D. G., Mulligan, C. J., et al. (2007). Beringian standstill and spread of Native American founders. PLoS One, 2(9), e829.

Tankersley, K. B. (1991). A geoarchaeological investigation of distribution and exchange in the raw material economies of Clovis groups in eastern North America. In A. Montet-White & S. Holen (Eds.), Raw material economies among prehistoric hunter-gatherers (Vol. 19, pp. 285–303). Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Publications in Anthropology.

Tolan-Smith, C. (2003). The social context of landscape learning and the late glacial-early postglacial recolonization of the British Isles. In M. Rockman & J. Steele (Eds.), Colonization of unfamiliar landscapes: The archaeology of adaptation (pp. 116–129). New York: Routledge.

Tolman, M. S. (2001). DhPg-8, from mammoths to machinery: An overview of 11,000 years along the St. Mary River. M.Sc. thesis in environmental design, University of Calgary, Calgary.

Trautmann, T. R. (1981). Dravidian kinship. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Trautmann, T. R. (2001). The whole history of kinship terminology in three chapters. Anthropological Theory, 1(2), 268–287.

Trautmann, T. R., & Barnes, R. H. (1998). Dravidian, Iroqouis, and Crow-Omaha in North American perspective. In M. Godelier, T. R. Trautmann, & F. E. Tjon Sie Fat (Eds.), Transformations of kinship (pp. 27–58). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Waters, M. R., & Stafford, T. W., Jr. (2007). Redefining Clovis: Implications for the peopling of the Americas. Science, 315, 1122–1126.

Waters, M. R., Stafford Jr., T. W., Kooyman, B., & Hills, L. V. (2015). Late Pleistocene horse and camel hunting at the southern margin of the ice-free corridor: Reassessing the age of Wally’s Beach, Canada. PNAS, 112(114),4263–4267.

Weiss, K. M. (1973). Demographic models for anthropology (Vol. 27). Washington, DC: Menoirs of the Society for American Archaeology.

Whallon, R. (1989). Elements of cultural change in the later Paleolithic. In P. Mellars & C. Stringer (Eds.), The human revolution: Behavioural and biological perspectives on the origins of modern humans (pp. 433–454). Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

Whallon, R. (2006). Social networks and information: Non-“utilitarian” mobility among hunter-gatherers. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 25, 259–270.

Wheeler, C. J. (1982). An inquiry into the Proto-Algonquian system of social classification. Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford, 13(2), 165–174.

Wilson, M. C., Visser, J., & Magne, M. P. R. (2011). Microblade cores from the Northwestern Plains at High River, Alberta, Canada. Plains Anthropologist, 56(217), 23–46.

Wobst, H. M. (1974). Boundary conditions for Paleolithic social systems: A simulation approach. American Antiquity, 39, 147–178.

Wobst, H. M. (1976). Locational relationships in Paleolithic society. Journal of Human Evolution, 5, 49–58.

Acknowledgments

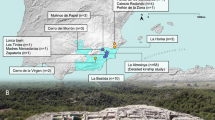

I am grateful to H.E. Mr. Olzhas Suleimenov, Ambassador to the Permanent Delegation of the Republic of Kazakhstan to UNESCO and the Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan to the United States of America for their kind invitation to take part in the Second International Conference on Great Migrations: from Asia to America. I extend my thanks to Aiym Zholdasbekova, Nurzhan Aitmakhanov, and Nurgali Arystanov for their assistance in arrangements, to Alan Timberlake for shepherding the conference, and to Michael Frachetti and Robert Spengler for guiding this publication. Kisha Supernant constructed the fluted point density map and Michael Semenchuk, the Cody Complex density map; Michael Billinger and Jason Gillespie helped in assembling and organizing ongoing versions of the Western Canadian Fluted Points Data Base applied here; Robert Dawe and Jack Brink (Royal Alberta Museum), Todd Kristensen (Archaeological Survey of Alberta), and David Meyer (University of Saskatchewan) provided valuable information on both fluted points and Cody Complex materials. We are all indebted to Eugene Gryba for his pioneering efforts to document fluted points in Alberta. Sunday Eiselt and I presented a related version of this paper at the 2011 of the Society for American Archaeology meetings in Sacramento as well as a poster at the Paleoamerican Odyssey conference in Santa Fe in October 2013; I thank Sunday for her contributions to this work. Columbia University and the Harriman Institute provided a delightful setting for the conference; given this context, I would like to stress that I owe much in my apprehension of Dene kinship to University of Alberta Emeritus Professor Michael Asch, a Columbia graduate who went on to become one of Canada’s most distinguished anthropologists of recent years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ives, J.W.(. (2015). Kinship, Demography, and Paleoindian Modes of Colonization: Some Western Canadian Perspectives. In: Frachetti, M., Spengler III, R. (eds) Mobility and Ancient Society in Asia and the Americas. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15138-0_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15138-0_10

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-15137-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-15138-0

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)