Abstract

In this chapter, we describe an empirically developed educational strategy that health profession training programmes could use to infuse students in the health professions with salutogenesis thinking and capability in their approach to patient care and health promotion activities. This strategy is based on years of research and teaching mental health, health promotion, and salutogenesis to students on bachelor, postgraduate, masters, and continuing education levels. Any educational strategy aiming to teach salutogenic practice should be grounded in the ontological stance that salutogenesis represents, and it should comprise salutogenesis as a body of knowledge, as a continuous learning process, as a way of working, and as a way of being. The overall objective is not the healing of diseases, but the facilitating and supporting of health-promoting processes leading to a person’s or group’s adaptive coping and enhanced ease and well-being. A key outcome of such training is that the student develops the capacity to manage herself in the salutogenic way. This means developing the capability called “self-tuning,” which is habitual self-sensitivity, reflection, and mobilizing of resources to maintain and improve one’s own health (“ease,” in Antonovsky’s terms). This is a form of self-care, the principles of which can be used by health professionals to assist patients and others to experience good health and well-being. A health professional’s “salutogenic capacity” is her degree of skill to help a person or group examine, mobilize, and deploy sufficient resources to achieve a shift towards the experience of good health and well-being. Salutogenic capacity can be expanded as part of the professional training, as described in this chapter. The methods learned can be applied after training, such that salutogenic capacity is strengthened and reinforced during the course of one’s career.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Salutogenesis

- Health promotion

- Health professionals

- Training

- Educational strategy

- Self-tuning

- Salutogenic capacity

Introduction

Developing a competent health promotion workforce is a key component of capacity building for the future and is critical to delivering on the vision, values and commitments of global health promotion (Barry, Allegrante, Lamarre, Auld, & Taub, 2009).

Barry and colleagues wrote this in 2009 and presented simultaneously the results from the Galway Consensus Conference on the development of core competencies for health promotion and health education. The core domains of competency agreed to at the meeting were catalyzing change, leadership, assessment, planning, implementation, evaluation, advocacy, and partnerships (Barry et al., 2009). At the seventh WHO Global Health Promotion Conference held in Nairobi the same year, Sir Michael Marmot described a dilemma concerning this very issue. He stated that The Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986) being the mission statement for Health Promotion , very clearly describes what to do and how to do it, but that too little is happening. Sir Michael claimed that this was not due to having too few resources or not seeing possible solutions, but due to lacking skills in translating what we know into good use where it’s needed (Lindström & Eriksson, 2010). The Nairobi meeting came up with two main strategies for developing the field of health promotion in the following years: (1) translating research findings into practice and (2) building competence in health promotion. Since Nairobi and Galway in 2009, there has been an ongoing effort to clarify what skills a health promoter needs to work systematically and purposefully.

We have been teaching mental health, health promotion, and salutogenesis to students on bachelor, postgraduate, and master levels, and to a variety of already trained health professionals for approximately 15 years now. Our teachings are directed primarily at people who are, and have been working actively in their professions for a good while and who want to expand their expertise in health promotion for using it in their professions. Therefore, during their education they need to learn how to translate theoretical knowledge into practical skills, and how to engage in health-promoting activities when returning to work with their acquired degrees. As we see it, promoting health is to identify and use the experienced scope of action one perceives to have in a given situation, and to do this in an ethically acceptable way, with emphasis on emphatic concern and social responsibility.

From a salutogenic perspective, health is strengthened or weakened depending on how resources are put into good use, and how everyday activities are organized and carried out. The consequences of health promotion initiatives are not just dependent on the activities in themselves, but also on how one implements them. Alongside gradually expanding their theoretical understanding, the students need to reflect upon and make use of their own practical experiences in a variety of exercises. The goal is that the students develop practical skills and relational competence when it comes to supporting and promoting health-promoting processes one-on-one, and at a group- and community level. We find that relational competence is the key to succeeding in this endeavor.

To support health professionals in developing their salutogenic understanding and health promotion skills, there is a need for more high-quality research and wider distribution of the resulting knowledge. Such research will potentially advise policy-makers and health service administrators to reallocate resources and make it possible for health workers to expand their competence and fill roles as health promotion practitioners as well (Catford, 2014; McHugh, Robinson, & Chesters, 2010). There is a need for health professionals to take on a more salutogenic (Lindström & Eriksson, 2010) and person-centered approach (McCormack & McCance, 2010), in order to understand individual needs in light of the contexts they are part of, and assist in keeping people well and living healthier lives.

In our experience, really grasping the differences and consequences of working within a salutogenic paradigm is difficult. Antonovsky himself was doubtful of the task: “I have no illusions. A salutogenic orientation is not likely to take over. Pathogenesis is too deeply entrenched in our thinking …” (Antonovsky, 1996, p. 171). We find that exploring and reflecting together with our students about tensions in and between the two different paradigms (salutogenesis vs. pathogenesis) is a very educational task that we return to often. It is also a constant task to consider how the two perspectives complement each other in public health and healthcare services (see Table 29.1).

However, our aim is that students return always to the understanding of:

-

Health as a continuum.

-

The normalcy of stressors and tension in everybody’s lives.

-

The need to understand the person in his/her context.

-

The activation and use of resources to counter tension.

-

The goal of adaptive coping and enhancement of health and well-being. These areas are useful for gradually understanding the important differences between the two perspectives.

Alongside this, we also stress that taking a salutogenic stance implies exploring what it could mean to apply a settings approach in each situation. The settings approach shifts the focus of interventions from the individual to creating conditions supportive of health and health behavior (Green, Tones, Cross, & Woodall, 2015). However, it does not minimize the need to understand the person in his/her context; the health-promoting activities chosen will always have to stem from such a person-centered approach.

When one’s work is inspired from a thorough understanding of salutogenesis, health professionals will encourage attitudes and actions that reflect knowledge about health, possibilities, and resources. This means, however, that the knowledge has to be integrated in the health professional in a way that reflects that she really understands what it means to focus on the promotion of health. We find that working salutogenically means that a health professional is in a continuous learning process in which she engages in creative interplay with individuals and groups to identify health determinants and mobilize resources that promote the sense of coherence, health, and well-being. All the core domains of competency suggested by Barry and colleagues (2009) are highly relevant, but there is a need to add a specific focus on the relational, conversational, and dialogue competency to practice one’s professional competency in a fully engaged way.

Teaching Salutogenesis in Different Settings

We will now give three different examples of educational programmes. These programmes are based on the theory and understanding presented above and more fully in the discussions below. In a variety of ways, we teach from this knowledge base. Every hour, every lesson, and every day of the programme only has a tentative plan. The level of success is highly dependent on our ability to read what is at stake and in play in the group of students, and to adjust to it. In other words, we constantly develop our own skills in self-tuning (Vinje & Mittelmark, 2006), building our own, and stimulating students’ salutogenic capacity (Vinje & Ausland, 2013) in a continuous gain spiral. Following the examples, we will give a more in-depth discussion of the principles and theoretical ideas presented.

Example 1: Teaching Salutogenesis to Health Promotion Generalists

This is a master’s degree programme for students from various health professions. It was originally developed to offer master’s students in health promotion a specialization in salutogenesis. The programme has eventually found its way to students in other master’s programmes and to health professionals currently working in their specific fields, and we include students from these different areas in a mixed group. The students meet for 3 days each month for a total duration of 3 months. The students have two individual reflection exercises during the programme, for example:

Individual Essay: Own Stress and Coping Narrative in Light of Salutogenesis

Describe one or two situations you usually experience as stressful. Be specific and describe the situation(s) as detailed as you can. Describe thoughts, feelings, and how you feel in your body and what you usually say and do in relation to the people involved. Describe then how you usually handle such situations. Focus again on bodily expression, thoughts, feelings, and relational factors. Reflect about your experiences in light of salutogenesis as described by A. Antonovsky.

These individual essays are written in an essayistic style suggested by Bech-Karlsen (2003) that we find helpful in developing sensibility, and thus helpful to assess achievement in relation to learning objectives. The essayistic writing style is about introspection and being able to describing specific situations from own lives and/or practice. It is a goal to learn to discriminate between describing what is, interpreting it, and reflecting on it (ibid). The purpose is to practice receiving signals from own senses, emotions, thoughts, and body reactions and to write these signals down, describing them as detailed as possible, and subsequently reflecting on what one has found and what it means when it comes to coping with one’s current situation.

The students work in the same groups of 3–5 members throughout the programme. The groups work together on a topic relevant to salutogenesis , and they also explore how to develop salutogenic group processes, for example:

Group Assignment , the Task Is Twofold

-

(1)

On the basis of a real or constructed health promotion programme, the group considers how to promote the well-being/quality of life in a selected setting (home, school, workplace, or community). The group describes the situation and discusses it in light of the salutogenic model of health as presented by A. Antonovsky.

-

(2)

The group aims at developing a salutogenic group process, and describes and reflects on the process in the group during their work on the task presented in (1).

At the last session, the group gives a 30-min presentation of their work and the group process. This is discussed with the other students and teachers. After this feedback, the group finalizes their assignment and:

-

The thematic part of the assignment is submitted and evaluated separately

-

The groups’ joint reflection on the group process is submitted and evaluated separately

-

Individual reflections on the group process are submitted and evaluated separately

An individual home examination is undertaken over 3 days, building on this same idea. Based on a real or constructed case to initiate and support a health promotion process, working one-on-one, in groups, in a workplace, or in the local community, the student describes and reflects in light of salutogenic theory and discusses their role and influence in the approach selected.

It is a goal that this programme is health promoting for the students attending it. We therefore strive to live as we preach. We believe students’ evaluation show that we have a strategy that supports this goal. Because of students’ evaluations, we cannot emphasize strongly enough this notion of being salutogenic in the learning environment; it is said by students to be crucial to their understanding of salutogenesis . Students’ evaluation also urges us to place great emphasis on the creation of groups to support the group process from day one in the programme, and to have the groups meet everyday that we are gathered. Below is an outline of the learning outcomes the programme aims to achieve:

Knowledge

-

The student has advanced knowledge of the salutogenic model of health as presented by Aaron Antonovsky.

-

The student has an overview of other salutogenic theories and relevant salutogenic research.

-

The student has advanced knowledge of the phenomena of health, disease, meaning, well-being, and quality of life in today’s society.

-

The student has a thorough knowledge of health-promoting processes in individuals, relationships, and groups.

Skills

-

The student can assess possibilities and challenges by adopting a salutogenic approach in practical health promotion and research.

-

The student has skills in using own practical experiences as a basis for systematic reflection on health-promoting processes.

-

The student has basic skills in supporting and promoting health processes in working with others.

-

The student can critically evaluate choices of methods and own role in health promotion work.

General Competence

-

The student has knowledge about the salutogenic perspective’s relevance and value in relation to the discipline of health promotion.

-

The student can critically evaluate values and ethical issues in applying a salutogenic approach in practical health promotion and research.

-

The student can critically evaluate moral dilemmas in efforts to promote and support health-promoting processes in others.

The learning activities are a mixture of lectures , practical exercises, reflections, and discussions, teamwork and individual work between sessions. Except for the first day, each day begins and/or ends with 30 min of reflection about the topics of the day. When this is to be done, the room is rearranged: the tables are removed and chairs are set in a circle. We focus on descriptive reflection (action/what have I done), analytical reflection (what did I learn) and constructive reflection (planning/ how can I improve) (see Table 29.2). Sometimes we take rounds in the circle of seated students , wherein all are invited to speak (however, it is always possible to pass). Other times we have an “open window,” where the one who has something on her/his mind takes the word. The focus is on the day’s theme; its contents, understandings, benefits, challenges, processes, interactions, and that may have come into play in the group during the day. The main objectives of these “reflection circles” are threefold:

-

1.

Increasing the learning effect of the current topic.

-

2.

Practicing reflection and practicing putting into words how it is to be part of the group, what one needs to understand more fully, what one needs to feel good in the group, and to progress in one’s professional development.

-

3.

Continuously assessing and evaluating the programme to allow for changes to reach the described learning outcomes.

Example 2: Teaching Group Leaders of Salutogenic Talk-Therapy Groups

Professional salutogenic healthcare places special responsibility on health professionals (Oliveira, 2015). Oliveira points out why, explaining that working salutogenically might involve supporting people in uprooting and changing health detrimental situations, counseling in establishing new relationships and activities, and facilitating and joining in dialogues about finding meaning in everyday life (ibid). These practices call for competence in assisting others in developing and activating resources such as social support and identity, arranging for appropriate challenges, thus promoting good coping experiences and subsequently, a stronger sense of coherence (Langeland, Wahl, Kristoffersen, Nortvedt, & Hanestad, 2007). In our work with salutogenic talk-therapy groups (Langeland et al., 2007), we find Oliveira’s claims to be highly relevant. Thus, these claims are important aspects for us to include in training programmes for mental health professionals who wish to lead such groups.

A salutogenic talk-therapy group is an intervention program developed for people with different mental health problems and consists of 16 talk-therapy meetings, which last for 2 h and 15 min each, as well as homework for a period of 16 weeks (for detailed description see Langeland & Vinje, 2013). Leading these groups in a salutogenic way implies special competence. Key is that the health professionals integrate the theoretical knowledge into a therapeutic use of self ‘the salutogenic way’. Accordingly, the focus for the group leader is to help the participant entering into a good circle or positive feedback loop between using one’s resistance resources and developing one’s SOC. Our experience is that these types of groups need a professional leader, a mental health professional that knows how to build both on their own, and their clients’ salutogenic capacity. Further, a salutogenic talk-therapy leader must be highly empathetic and sensitive to the process of relating to people as whole persons. In talk-therapy groups, a central ideal is that conversations between participants and between participants and the group leader should be characterized by being a therapeutic dialogue (Egan, 2002). The aim is to develop a group atmosphere characterized by mutual, egalitarian relationships, in which the tenor of conversations between the group leaders and participants is similar to those between the participants themselves (Antonovsky, 1990; Gilligan & Price, 1993; Rogers, 1980).

Traditionally, mental health professionals learn to maintain their distance and stay in control. This is important, though research demonstrates that intimacy, spontaneity , and personal engagement may have therapeutic effects (Borg, 2007; Langeland & Wahl, 2009). Antonovsky (1987, p. 9) maintains: “When one searches for effective adaptation of the organism, one can move beyond post-Cartesian dualism and look to imagination, love, play, meaning, will, and the social structure that foster them.” In teaching future group leaders, we also find inspiration in Yalom (1975) who identifies eleven interdependent therapeutic group aims: to give hope, to encourage universalization, to share information, to engender altruism, to try new approaches, to develop social competence, to promote vicarious learning, to promote learning between people, to encourage group solidarity, to achieve catharsis and to encourage existential viewpoints. Thus, the group leader’s job is to focus on creating a conversational and interactional climate that will promote a desirable development in the participants. By acknowledging his or her inability to understand the participant fully, he or she strives toward meeting the participant with an attitude combining unconditional positive regard, empathic concern, and authenticity (Langeland & Vinje, 2013; Rogers, 1957). The idea is to demonstrate person-centeredness in practice, actively listening to the participants’ story, respecting and acknowledging that the participant is his own expert (Langeland et al., 2007). The participant is the one fully knowing his or her unique situation, including experiences of pain, suffering, and concerns (Rogers, 1957). From a salutogenic perspective, the group leader has a role as a dialogue partner, achieving a balance between listening empathetically to participants’ difficulties while taking into account their strengths and resources (Duncan, Miller, Hubble, & Wampold, 2010). It is a confidence in people’s innate potential for growth and development that should be in the forefront of the group leader’s mind. We emphasize in our teachings that the group has a potential for facilitating self-understanding and self-definition, and thus the group leader holds a considerable responsibility to build the type of relationship that can inspire hope. According to Stanhope and Solomon (2008) this helps bolster against the negative impact of societal stigma and marginalization, an important goal for health promotion.

This specific education program consists of four parts : (1) the salutogenic model of health (2) knowledge translation of the model into mental healthcare settings, (3) practical strategies and (4) development of clinical competence. Our students have evaluated the program as meaningful and very useful in understanding how a salutogenic health focus may be practiced. Facilitating health-promoting process and supporting others (one-on-one, and in groups) during such processes is central in our teachings. We do this by use of the different theoretical and salutogenic perspectives we have presented above, and will discuss further below. We rely heavily on what we describe as dialogue-based lectures. These are inductive methods inviting the students to explore his or her own experiences with a certain phenomenon or topic, and the teacher lets what the students find be the starting point of joint reflections on the topic and for her subsequent lecture. The focus is on interaction processes and on becoming a salutogenic group leader. The aim is that the students develop professional and ethical understanding, and that they are able to choose ethical sound methods in specific situations. Central to our teachings is thus experience-oriented learning, and we arrange for ‘realistic sessions’ in which the students can practice together both as a group leader and as a participant of a talk-therapy group. The teaching methods are lectures, dialogues, individual studies, and practical exercises in groups.

Our research shows that the group leader’s salutogenic approach helps increase participants’ awareness of and confidence in their potential, their internal and external resources and their ability to use these to increase their SOC, coping, level of mental health and well-being. The intervention has been evaluated in a randomized controlled trial study, showing positive effects on the sense of coherence, and it has been positively evaluated in its utility for everyday living (Langeland et al., 2006). Other studies confirm that salutogenic talk-therapy groups strengthen the sense of coherence , mental health and well-being; this salutogenic approach increases participants’ awareness of and confidence in their potential, their internal and external resources and their ability to use them, and thus increase their coping and sense of coherence (Langeland & Vinje, 2013).

Example 3: Students Practicing Participatory Methods in the Salutogenic Way

Empowering and enabling individuals and groups are fundamental principles in health promotion, and health promotion practitioners need to master different kinds of participatory and partnership methods (Green et al., 2015). However, how do we know that what we do as health promotion practitioners actually work? Traditionally, students in health promotion are trained to use action-learning methodology in order to increase their ability to practice reflection in action (Reason, 1988; Schön, 1983). Applying a salutogenic orientation to one’s health promotion work should most certainly involve developing skills of reflection about own practice. Yet, the weakness of the traditional training as we see it is that it does not problematize the process that underlies practitioners’ reflection in and of practice. Reflection is a cognitive process, which may lose some of its development and improvement power if one does not take into account the pre-reflexive, pre-cognitive mode of sensibility (Vinje, 2007). Participatory methods are often designed to invite people to share their experiences in order to improve a setting or a situation, and the methods aim at making people feeling secure and empowered in doing so. However, we argue that participatory methods have the power to cause harm if not facilitated with the skills of both sensibility and reflection (Ausland & Vinje, 2010). We find that practicing self-tuning individually and together in groups (for example in a workplace setting) is helpful in bringing about changes at a group level, and in doing so, the group’s salutogenic capacity may be strengthened. In this third example, we present one example of how students can train and practice introspection, sensibility, and critical reflection in action.

This example is a student-led assignment in which the students plan, arrange, and evaluate their own dialogue conference for co-students. The problem they are set to investigate by the use of participatory methods is: “How can a master’s program in health promotion promote health for its students?”

At the end of the conference, the aim is that the students have gained experience in planning and performing a conference using participatory methods, and that they have made plans for action to improve own situation as master’s students. Central to both method and result is salutogenesis. The core of the salutogenic understanding is underpinning every action: (1) health as a continuum, (2) the normalcy of stressors and tension in everybody’s lives, (3) the need to understand the person in his/her context, (4) the activation and use of resources to counter tension; and (5) the goal of adaptive coping and enhancement of health and well-being. When these ideas become guiding principles, it becomes clear that every action entails an invitation to every participant to bring forth her own experience. The facilitator’s ability to ask for, listen to, and really notice what is at stake is vital to the success and relevance of the reflection. The stages in the conference are (1) Planning and organizing (2) Searching for research questions (3) Planning and performing facilitating participatory methods (4) Continuous evaluation by reflecting on action and reflecting in action (5) Documenting the process and disseminating the results.

During the conference, the students change roles as facilitators and participants, and they all reflect individually on what they experience by writing reflection notes during the process (see Table 29.3). Traditionally, one often moves directly to reflecting in pairs or in groups. Taking the salutogenic principle of understanding the person in her context seriously, we suggest using the idea of sensibility and allow individual introspection and self-reflection about the subject prior to group reflection. Further, we arrange for the students to take time-outs to share their reflection notes in groups during the process, (every group consists of both facilitators and participants). At the end of a session, the group develops a new reflection note together, reflecting upon the groups’ learning processes, based on their individual inputs into the reflections. Eventually, all reflection notes, both group notes and individual ones, are posted on the students Virtual Electronic Classroom, for everyone to read and learn from. All stages in the dialogue process are described, reflected upon with an aim of improving the process both at an individual and at group level. This way, the students practice self-tuning and may experience ways of promoting one’s own and the group’s salutogenic capacity. We find that a crucial advantage is that all stages of the students’ learning processes are transparent.

Teaching by Doing and Teaching by Being

In the three examples above, we have introduced several theoretical concepts that are central to our teaching strategies. Many of these concepts are empirically derived from years of research. In the sections below, we more fully present and discuss these ideas and their relevance in the application of salutogenesis in the training of health professionals.

Health promotion skills of the individual must be understood as part of the setting the health professional is working in. Applying new knowledge is not just an individual exercise, but happens in a larger political and ideological context. All methodologies used in health promotion work can be encapsulated and have limited effect if one does not have a perspective on learning as something ongoing and expanding broader than own practice. Taking the philosophical formula suggested by Lindström and Eriksson (2010) into account, real health promotion is exercised through participant-oriented methodology, for example in the form of dialogue or discussion groups of various kinds. Health promotion methods have therefore an innate moral goal to facilitate democracy and participation adapted to different settings and participants (ibid).

The overall aim of health promotion is to strengthen health and quality of life of those involved. However, methods used to promote involvement, participation, and quality of life can be perceived as a stressor by those involved, and like every other stressor, its effect can be health promoting, health neutral, or health detrimental. No practical method of health promotion is good or bad in itself. It is thus important for the health professional to understand how a particular method changes from idea to practical reality when filtered through him or her as health promoter.

Our educational strategy following from this line of reasoning involves a lot of reflecting on own practice. It includes consciously bringing the health professionals’ experiences into the classroom to scrutinize them in light of their new knowledge. It also requires us to design practical lessons so that our students can practice together to build their self-awareness, relational sensitivity and ability to reflect. Moreover, we aim at helping the health professionals further develop their skills in carrying out dialogues. Together, we explore what it means to live a salutogenic life, and how to become a salutogenic dialogue partner. We introduce the art of wondering (Schibbye, 2007) and the power of acceptance, emphatic concern and authenticity (Langeland & Vinje, 2013; Rogers, 1957). We find it is necessary to focus not only on what to do and how to do it. Our experience is that it is vital to focus also on how to be salutogenic. Therefore, it all comes down to teaching by doing and teaching by being, the latter being by far the more challenging.

Our education strategy, then, comprises the three perspectives: what to do, how to do it, and how to be it. (See Table 29.3)

Different Logics, Knowing Them and the Skill of Toggling Between Them

Table 29.3 presents a linear outline of the content of our educational strategy. However, knowing that Antonovsky was inspired by systems theory while developing salutogenesis (Antonovsky, 1979), and taking the settings approach seriously, we would like to point out that such a Table, while compatible with rational analytical thinking, does not give the whole picture of what salutogenic competence is about.

A more accurate display of the strategy, however much more complex, would be a dialogical relational model showing how every part of the strategy is linked together with arrows pointing in every direction, connecting every part, showing how every part is affecting each other reciprocally in feedback-loops. Acquiring salutogenic skills involves focusing on theories and values and on the “doing” part and “being” part simultaneously. In real life, there is nothing linear about it. The goal is that the health professional understands these reciprocal feedback-loops and that assessment of a practical situation and resultant acting becomes increasingly reflexive. In our experience, gaining this level of competence requires lot of reflection and acceptance of the aforementioned stance: learning salutogenesis is a lifelong learning process. It develops skill that enables the health professional to move between different logics such as the rational analytic one vs. the relational dialogical one, and the doing vs. being aspects of salutogenic work.

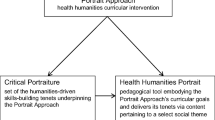

Self-Tuning for Building Salutogenic Capacity

Research shows that self-tuning is an important competence for health promotion (Bakibinga, Vinje, & Mittelmark, 2012; Vinje, 2007; Vinje & Ausland, 2013; Vinje & Mittelmark, 2006). The concept of self-tuning has evolved from exploring in-depth, using inductive qualitative designs, the nature of job engagement among thriving Norwegian community health nurses, and investigating how job engagement is maintained and promoted (Vinje, 2007; Vinje & Mittelmark, 2006). The concept has been further explored among Ugandan nurses (Bakibinga et al., 2012), and in the work-life of nurses and other health professionals in municipal health services in Norway (Vinje & Ausland, 2013). The experience of meaning, particularly in the sense of being useful and experiencing existential significance, seems essential for health professionals’ engagement and work-related well-being (ibid). When the inner drive of the healthcare worker resonates with his or her profession and finds its expression in his or her current work, it creates an inspirational force, which sustains and enhances the experience of meaning, zest, and vitality (see Fig. 29.1 for the original self-tuning model).

The self-tuning model of self-care (Vinje & Mittelmark, 2006)

In our teaching, we link this understanding with the salutogenic concept of boundaries—Antonovsky clarifies that while the sense of coherence refers to a generalized, long lasting way of seeing the world and one’s life in it, one does not need to see one’s entire world as coherent, we all set boundaries (Antonovsky, 1987, pp. 22–23):

The boundary notion suggests that one need not necessarily feel that all of life is highly comprehensible, manageable and meaningful in order to have a strong SOC. (…) I do not think it is possible to so narrow the boundaries as to put beyond the pale of significance four spheres—one’s inner feelings, one’s immediate interpersonal relations, one’s major activities, and existential issues (death, inevitable failures, shortcomings, conflict, and isolation)—and yet maintain a strong SOC.

In his discussions on boundaries, Antonovsky also points out that different persons have different breadths to one’s boundaries, and that a person with a strong sense of coherence might maintain his or her view of the world as coherent by being flexible about the areas included within the boundaries considered significant (ibid). He thereby gives a nod in the direction of existential curiosity in order to tune and increase one’s ability to know and find one’s significant areas of life, and being flexible about them. We have added this insight into the part of the self-tuning model that illustrates the inspirational force, this time of life engagement (see Fig. 29.2.)

As illustrated in the original self-tuning model, the match between inner drive/calling and vocation seems to act as a catalyst for processes leading simultaneously to high job engagement and to highly diligent dutifulness, which in turn may inhibit engagement (Vinje, 2008; Vinje & Mittelmark, 2007). In line with a salutogenic perspective, we can thus argue that every person, at all times, will be in a position for health-promoting and detrimental factors to influence his or her situation simultaneously, in line with the ontological stance of heterostasis in salutogenesis (Antonovsky, 1979).

The challenge, which is of relevance to our topic, is to explore the dynamics, and to devote attention to understanding positive and negative factors alike (Vinje & Ausland, 2013). Although Antonovsky is somewhat unclear even if extensive in his ponderings about the meaning of health, he seemed to believe that salutogenesis is about focusing on movement toward the ease pole of the health ease - dis/ease continuum—regardless of how far into the positive that continuum might stretch. We believe, however, giving attention to that which is in a given moment including detrimental sensations and factors is important to be able to halt and turn a negative development. In pausing and asking salutogenic questions like: “what now?”, “what do I/we need,” “what will bring health and ease in this situation,” “who do I/we need to talk to?”, “what do I/we usually do that works?”, “what else is important?” “what makes my heart sing?” “how do I/we feel when it feels right?” “who and what can help?” movement towards ease can yet again begin and be the object of our concern. We find that the mediating process in the self-tuning model, the actual “tuning” practice is helpful in this process. For the purpose of our teachings, it is depicted like this:

In our teaching, we introduce and seek to explore self-tuning as a health-promoting capability. The Self-tuning Model has proven useful to outline topics in teaching about salutogenesis, and students in our programmes react well to its use. However, they are made to understand that self-tuning is each individual’s and group’s practice, and that it does not hold detailed answers to specific situations. Self-tuning is the process of exploring, sensing, reflecting, and thus reacting to a situation with increasingly more adaptive coping. The self-tuning process can be learned; however, it requires conscious work over time. Our students express that the model is meaningful, and we find that self-tuning provides an essential basis for discussions on and reflections around health-promoting processes and the enhancement of salutogenic capabilities.

Therefore, we propose that self-tuning is a tool for sensing what is at play in a certain situation, for reflecting upon it, and for reacting to it in a health-promoting manner. Our teaching experiences show that in combining the actual “tuning” (Fig. 29.3) with the “exploration of significant life areas” (Fig. 29.2), the self-tuning model helps structure and facilitate health-promoting processes when working both one-on-one and in groups. We propose that it relates to enhancing a sense of coherence and health and well-being as illustrated here:

This is, once again, not a linear process, but a systemic relational one, meaning that the arrows in fact are doubled-arrowed, connecting every aspect of the process to one another.

Teaching Reflection

We will now dive deeper into teaching reflection and sensibility. It is important for the health professional to learn to reflect upon not only what he/she is doing, but why, and how, and the effects on others when he or she is the one doing it. Moreover, it is vital to understand how the persons and the particular setting perceive the method used by the health professional, and how the method relates to the purpose of the initiative. As we see it, and aim to teach it, the health professional needs to learn how to include reflection into each initiative. How are the effects of the health promotion activities assessed in the setting? Who assesses the effects, and how can these assessments help to improve and develop the methods used? The learning has its focus on what happens when one is learning and that learning is ongoing and never ending, and not so much on any particular results. Our teaching includes understanding the ontological stance that salutogenesis represents, and we move from theoretical understandings of salutogenesis as a body of knowledge, as a continuous learning process, as a way of working, and as a way of being, to reflecting on more or less successful implementation in light of our students’ practical experiences. Through learning the skill of reflecting upon one’s practice, the initiative undertaken has the potential of becoming health promoting. In health promotion, through reflection, one aims at developing structures that facilitate systematic contemplation about practice and practical approaches. Reflection is, however, not always innocent and without pain, it can be both painful and energy draining to discover one’s own or one’s colleagues’ capabilities or lack thereof (Ausland & Vinje, 2010). The ability to reflect critically with others can be health promoting because it helps identify resources and develop control and oversight of a situation. Being salutogenic entails in this respect to demonstrate an attitude of wondering and a will to explore and look at a situation from different perspectives, and to show a will to learn together, and facilitate continual learning processes. All this taken into account, in our teaching as in our research, we keep coming back to the question: how do we know that what we reflect upon is relevant for the actual situation?

Teaching Introspection and Sensibility

Although reflection is a vital part of the sensing/reacting process we call self-tuning (Vinje, 2007; Vinje & Mittelmark, 2006), reflection by itself is likely not enough to ensure life experiences being translated into better health and well-being. Engaging in health-promoting processes finds its basis not only in reflection, but in a talent and habit of introspection, sensibility, reflection and a readiness to act when needed, which converts into active, adaptive coping. The “tuning” process is characterized by a person’s or group’s ability to pause, to concentrate inwardly and to reflect on one’s own situation. Through doing this, one monitors one’s personal and environmental states and the degree to which one’s situation is characterized by engagement and well-being.

In this way, one attempts to protect meaning, zest, and vitality in an ongoing process. Nortvedt and Grimen (2004) present the construct of sensibility as being a capacity desirable for people in the helping professions to develop, in order to sense and understand the experience of being a patient. Furthermore, Nortvedt and Grimen (2004) claim that sensibility, in its receptiveness towards the expressions of others, also encompasses a moral dimension that involves responding ethically to these expressions. Sensibility as it is used in self-tuning expands this understanding to including a pre-cognitive apprehension of one’s own inner state and the receptiveness of one’s own vulnerability (Vinje & Mittelmark, 2006). We suggest that sensibility may awaken an impulse, a wish, or a sense of ethical responsibility that calls for the taking care of one’s own health (Vinje, 2007). We thus suggest that sensibility is a central feature for health promotion, directed towards both patients/clients and professionals.

To heighten our students’ sensibility , we use a variety of exercises, one of which is writing essays (Bech-Karlsen, 2003) based on concrete situations from a student’s own life and/or practice. Our students are invited, using introspection, to describe their experiences related to a specific event, in as detailed and nuanced a manner as possible. The task is to practice grasping signals from own senses, emotions, thoughts, bodily reactions, and existential depths that come into play in the situation, and to practice describing these without judging them as good or less good reactions. What one finds only has status as that which is right now. What one chooses to do with that finding is, however, a matter for reflection. Our students thus practice noting, discovering and accepting without judgment that which gives content to individual reflection and to reflection in groups. The assumption is that through introspection one’s sensibility will provide relevant and useful reflection processes, which in turn will provide a broadened, experienced scope of action and relevant active, adaptive coping.

Sensibility has its own language that students learn to access through these descriptive texts. Prior to the actual essay writing, we sometimes use warm-up exercises such as listening to music, doing easy yoga, meditations, breathing exercises, visualizations, going for walks, etc. We find that there cannot be a fixed plan as to which exercise to use. Each person and each group is different and unique, and every plan is only tentative. The teacher (and health promoter) needs to work on her own sensibility in order to design effective lessons in this respect.

Summing up

To sum this chapter up, we would like to emphasize that any educational strategy aiming to teach salutogenic practice should be grounded in the ontological stance that salutogenesis represents (see Table 29.1). Such education should be comprised of salutogenesis as a body of knowledge, as a continuous learning process, as a way of working, and as a way of being. It is important to remember that the overall objective is not the healing of diseases, but the facilitating and supporting of health-promoting processes leading to a person’s or group’s adaptive coping and enhanced ease and well-being. We find that helping students explore and reflect upon their experiences in light of the two different orientations, salutogenesis and pathogenesis, is best done as an ongoing process.

A key outcome of training students in salutogenesis is that the student develops the capacity to manage herself in the salutogenic way. To facilitate this development, we strongly suggest introducing and working on increasing the capability called “self-tuning,” which is habitual self-sensitivity, reflection, and mobilizing of resources to maintain and improve one’s own health (“ease,” in Antonovsky’s terms). This is a form of self-care, the principles of which can be used by health professionals to assist patients and others to experience good health and well-being. A health professional’s “salutogenic capacity” is her degree of skill to help a person or group examine, mobilize, and deploy sufficient resources to achieve a shift towards the experience of good health and well-being. One’s salutogenic capacity can be expanded as part of professional training and after training, such that salutogenic capacity is strengthened and reinforced during the course of one’s career. There are surely many ways to achieve this. However, in our experience the equal emphasis on what to do, how to do it, how to be it, is a key factor in succeeding in training health professionals in salutogenesis. Therefore, it all comes down to teaching by doing and teaching by being, the latter by far the more challenging. However, comprising the three perspectives is, in our experience, the most effective way to teach salutogenesis.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Antonovsky, A. (1990). Pathways leading to successful coping and health. In M. Rosenbaum (Ed.), Learned resourcefulness: On coping skills, self-control, adaptive behavior (pp. 31–63). New York: Springer.

Antonovsky, A. (1996). The sense of coherence. A historical and future perspective. Israel Journal of Medical Sciences, 32, 170–178.

Ausland, L. H. & Vinje, H. F. (2010). Når det tause får ord på seg: Etiske overveielser i et forskningsprosjekt om nærvær. [When the unspoken becomes voiced—ethical considerations in a research project on the phenomenon of presence]. In J. K. Hummelvoll, E. Andvig, & A. Lyberg (Eds.), Etiske utfordringer i praksisnær forskning. [Ethical challenges in research in practice settings]. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademiske Forlag.

Bakibinga, P., Vinje, H. F., & Mittelmark, M. B. (2012). Self-tuning for job engagement: Ugandan nurses’ self-care strategies in coping with work stress. International Journal for Mental Health Promotion, 14(1), 3–12.

Barry, M. M., Allegrante, J. P., Lamarre, M.-C., Auld, E., & Taub, A. (2009). The Galway Consensus conference: International collaboration on the development of core competencies for health promotion and health education. Global Health Promotion, 16(2), 5–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1757975909104097.

Bech-Karlsen, J. (2003). Gode fagtekster. Essayskriving for begynnere. [Good Texts. Essay Writing for Beginners]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Borg, M. (2007). The nature of recovery as lived in everyday life. Doctoral Dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

Catford, J. (2014). Turn, turn, turn: Time to reorient health services. Health Promotion International, 29(1), 1–4. doi:10.1093/heapro/dat097.

Duncan, B. L., Miller, S. D., Hubble, M. A., & Wampold, B. E. (2010). The heart & soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Egan, G. (2002). The skilled helper: A problem-management and opportunity-development approach to helping (7th ed.). California: Pacific Grove.

Gilligan, S., & Price, R. (1993). Therapeutic conversations. New York: W.W. Norton.

Green, J., Tones, K., Cross, R., & Woodall, J. (2015). Health promotion, planning and strategy. Washington, DC: Sage.

Langeland, E., Riise, T., Hanestad, B. R., Nortvedt, M. W., Kristoffersen, K., & Wahl, A. K. (2006). The effect of salutogenic treatment principles on coping with mental health problems—a randomised controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 62, 212–219.

Langeland, E., & Vinje, H. F. (2013). The significance of salutogenesis and well-being in mental health promotion: From theory to practice. In C. Keyes (Ed.), Mental well-being: International contributions to the study of positive mental health (pp. 299–329). Dodrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-5194-1.

Langeland, E., & Wahl, A. K. (2009). The impact of social support on mental health service users’ sense of coherence: A longitudinal panel survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(6), 830–837.

Langeland, E., Wahl, A. K., Kristoffersen, K., Nortvedt, M. W., & Hanestad, B. R. (2007). Sense of coherence predicts change in life satisfaction among home-living residents in the community with mental health problems: A one-year follow-up study. Quality of Life Research, 16(6), 939–946.

Lindström, B., & Eriksson, M. (2010). The Hitchhiker’s guide to salutogenesis: Salutogenic pathways to health promotion. Helsinki: Folkhälsan Research Centre, Health Promotion Research and the IUHPE Global Working Group on Salutogenesis (GWG-SAL).

McCormack, B., & McCance, T. (2010). Person-centred nursing: Theory and practice. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-7113-7.

McHugh, C., Robinson, A., & Chesters, J. (2010). Health promoting health services: A review of the evidence. Health Promotion International, 25, 230–237.

Nortvedt, P., & Grimen, H. (2004). Sensibilitet og Refleksjon: Filosofi og Vitenskapsteori for Helsefag [Sensibility and reflection: Philosophy and theory of science for health professions]. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

Oliveira, C. C. (2015). Suffering and salutogenesis. Health Promotion International, 30, 222–227. doi:10.1093/heapro/dau061.

Reason, P. (Ed.). (1988). Human inquiry in action. Developments in new paradigm research. London: Sage.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions for therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95–103.

Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of being. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Schibbye, A.-L. L. (2007). Livsbevissthet—om å være tilstede i eget liv [Life consciousness—to be present in own life] (2nd ed.). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Stanhope, V., & Solomon, P. (2008). Getting to the heart of recovery and their implication for evidence-based practice. British Journal of Social Work, 38, 885–899.

Vinje, H. F. (2007). Thriving despite adversity: Job engagement and self-care among community nurses. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Bergen, Bergen. ISBN 978-82-308-0480-3.

Vinje, H. F. (2008). Spenningsfylt omsorgspraksis og selvomsorg: Hvordan kan jobbengasjement bevares og stimuleres i sykepleien? [Tension-filled care practices and self-care: How can job engagement be preserved and stimulated in nursing practice?]. Tidskriftet Kreftsykepleie, 24(4), 6–13.

Vinje, H. F., & Ausland, L. H. (2013). Salutogent nærvær fremmer helsefremmende arbeidsliv. Social Medisinsk Tidskrift. 6/2013, ss. 810–820. [Salutogenic Presence supports a health-promoting work life] (pp. 890–901). Retrieved from http://www.socialmedicinsktidskrift.se/index.php/smt/article/view/1086/880.

Vinje, H. F., & Mittelmark, M. (2006). Deflecting the path to burnout among community health nurses: How the effective practice of self-tuning renews job-engagement. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 8(4), 36–47.

Vinje, H. F., & Mittelmark, M. (2007). Job engagement’s paradoxical role in nurse burnout. Nursing and Health Sciences, 9, 107–111.

WHO. (1986, November 21). Ottawa Charter for health promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion Ottawa, 1986—WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1.

Yalom, I. D. (1975). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vinje, H.F., Ausland, L.H., Langeland, E. (2017). The Application of Salutogenesis in the Training of Health Professionals. In: Mittelmark, M., et al. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_29

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_29

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-04599-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-04600-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)