Abstract

After the long period of forced work from home, many knowledge workers have not only developed a strong habit of remote work, but also consider flexibility as their personal right and no longer as a privilege. Existing research suggest that the majority prefers to work two or three days per week from home and are likely to quit or search for a new job if forced to return to full time office work. Given these changes, companies are challenged to alter their work policies and satisfy the employee demands to retain talents. The subsequent decrease in office presence, also calls for transformations in the offices, as the free space opens up opportunities for cutting the rental costs, as well as the other expenses related to office maintenance, amenities, and perks. In this paper, we report our findings from comparing work policies in three Nordic tech and fintech companies and identify the discrepancies in the way the corporate intentions are communicated to the employees. We discuss the need for a more systematic approach to setting the goals behind a revised work policy and aligning the intensions with the company’s actions. Further, we discuss the need to resolve the inherent conflicts of interest between the individual employees (flexibility, individual productivity, and well-being) and the companies (profitability, quality of products and services, employee retention, attractiveness in the job market).

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

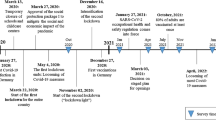

In March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, most tech companies sent their employees for forced work from home (WFH). Few years later, many knowledge workers still continue voluntary work from home with the preference for at least two or three days per week [1,2,3]. The reasons for this are manifold, the main being the unwillingness to commute [2], but also simply due to a strong habit of remote work developed during the pandemic [2]. As a result, many consider flexibility a personal right and no longer a privilege [1], and express readiness to quit or search for a new job if forced to return to full time office work [3]. Given these changes, companies are challenged to alter their work policies and satisfy the employee demands for individual flexibility (often associated with personal well-being and work/life balance [4]) to retain talents [1]. But are individual interests aligned with the team and corporate interests? After all, software engineering is a social activity and focuses on close cooperation and collaboration between all team members [9] and across teams in the organization [10].

The overall goal of our research is to evaluate the state of hybrid working to understand whether employee preferences to work from the office and office presence are changing, whether office presence matters, and if it matters, how can companies encourage employees to return (and how not to discourage the office presence). Despite the rise in research activity on hybrid work, there is still a lot more to be understood about hybrid development to provide rigorous and relevant evidence-based guidance for practice [6]. In this paper, we compare work policies of three Nordic tech and fintech companies that institutionalized flexibility. Our research is driven by the following question:

RQ1: What is the desired office presence in a company?

RQ2: What corporate actions support the desired office presence?

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the key findings from related research. Empirical cases and methodology are presented in Sect. 3. Section 4 is dedicated to the results, and a concluding discussion is found in Sect. 5.

2 Background

Our research of 16 companies and 26 policies in early 2022 demonstrated that WFH policies are divided into three main types: (1) decentralized WFH regulation, (2) centrally regulated onsite/offsite workdays, and (3) centrally regulated proportion of time spent on onsite/offsite, or a combination of these options [1]. Roughly half of 26 studied policies had decentralized WFH regulations with increased levels of flexibility (1), while the other half had centrally regulated onsite workdays, or the proportion of time spent working from home (2 and 3). Few opted for unlimited WFH, similarly to Facebook, Square, Shopify and Slack, who have established policies of long-term and even permanent WFH [6].

Our recent dialogs with the companies suggest that the initial regulations were often related to either the best guesses about the situation or the fears of losing employees or becoming unattractive in the eyes of the new hires, which is also reported in multiple related studies [3]. At the same time, many managers reveal that they prefer employees to return. Such announcements have been received with increasing criticism, as can be illustrated by the exchange of letters between Apple management and employeesFootnote 1 Footnote 2. Like Apple, many tech companies, even those formally opting for increased flexibility initially, hoped for a gradual increase in office presence. Yet, the actual state of remote work shows that not many people are returning to fulltime (or close to fulltime) work in the office [1,2,3] and the work has become increasingly hybrid [5]. In contrast to the benefits of being attractive as a workplace and retaining the talents that value flexibility, research started reporting the disadvantages of fully remote and hybrid work [7, 8], returning the considerations about the mandatory office presence. Examples of companies, disillusioned with the actual state of hybrid work, include Apple, Amazon, and Twitter, who pushed for more presence through the formal changes in the work policies. However, research on this topic to date is scarce and largely based on assumptions [6].

3 Methodology

In this paper, we report our findings from studying work policies in three tech and fintech companies, Case A and B (Sweden) and Case C (Sweden and Norway) (see the details of each company in the Findings section). Company names are not disclosed for anonymity. Our research is qualitative in nature and exploratory in purpose. In all three cases, we conducted semi-structured interviews with managers involved in defining the new work policies or responsible for their implementation to discuss how the policies are introduced and supported, and corporate intentions related to office presence (See Table 1). Our findings were discussed with middle managers in each company, and we additionally captured reflections and actions supporting or hindering the corporate strategies. We also visited the premises and captured office observations.

Data analysis was driven by our RQs. We first classified the corporate strategies (Fig. 1) and captured the reasons for the policies (Table 2). Based on the intended office presence, as seen by the management, attitude towards remote work, and necessity for the office space, we identified five corporate strategies, which include: office-based, office-first, hybrid, remote and remote-first (see Fig. 1). We then performed qualitative open coding to identify intentions conveyed in the policy document and the announcements sent to the employees and corporate actions supporting or hindering these intentions (e.g., in the changes at the workplace). Later, these intentions and actions were mapped to the five corporate strategies and studies for alignment.

4 Findings

4.1 Corporate Policies with Respect to Remote Work

Work policies studied specify the rules that regulate the degree of office/remote work classified into the five possible strategies (see Fig. 1). The five strategies often reflect the intended office presence and the use of office space.

In the following, we classify the three studied cases according to these five strategies, based on their policies, the announcements made by the management, and by the actions and changes related to the office space, workplace and the other perks offered by the companies. Our findings are summarized in Table 2.

4.2 Remote work policy in Case A

Case A is a Swedish branch of an international tech company working in the electronics industry. Upon reopening of the offices after the pandemic, the company offices were quite empty with many employees working remotely. The managers explain this with the trend to focus on one’s own flexibility first, what they call the “I over We” culture. To change this attitude and to facilitate teamwork, the company decided to implement a hybrid work policy permitting employees to work from home 2–3 days per week. The motivation behind the mandatory office days, as the manager explained, is related to the needs of the teams:

“Team days are important. […] Some tasks take a bit longer time if you do them digitally, it is preferred to meet when you have problem solving and creative tasks, since doing them on a distance requires other skills from a leader to manage. Finally, decision-making requires presence”.

To further support the return of the employees to the office, it was decided to negotiate the change of the canteen with the landlord, and even influence the choice of the menu on certain days. However, the policy in Case A is not strictly monitored, and the offices still have not been filled. In fact, many employees were reported to have a feeling of sitting in an empty office. Due to this reason and because of the relocation of some units to a new office and the end of a rental contract, the company decided to downsize the office by reducing the space from four to two floors. This has increased the density of the employees and made the environment seem more social. Interestingly, unlike many other companies, this has not resulted in the limited space. As a manager explains:

“We have downsized, made the office smaller, and we have also renovated and changed some areas. But we have seats for all, it is still possible to fit everyone. The downsizing primarily affected the unused space”.

One potential factor that perhaps did not support the return of the employees to the offices is the renegotiated conditions for the parking lot, which cancelled the free parking and free charging stations for electrical vehicles. However, the employees were said to not complain and to understand the reason for the cost.

4.3 Remote Work Policy in Case B

Case B Sweden is one of the sites of a large international company delivering software-intensive systems to the telecommunication market that employs around 500 people in the studied corporate site. After the pandemic, the company decided to focus on increasing the office presence. For long, there have been no renovations or downsizing in the office, and there is still space for everyone. Corporate and site management repeatedly emphasized the importance of helping and supporting colleagues over focusing entirely on one’s own tasks, as well as innovating and driving the corporate culture. These intentions are largely rooted in a belief that some tasks cannot be done effectively when everyone works remotely. However, office presence after the pandemic is not high, especially in larger cities.

When it comes to the policy, the introduced remote work rules are very broad and demand employees to work from the office “at least 50% of the time during a calendar year”. Many agree that the policy is very vague and hard to follow, as a manager explains – “It is not controlled, nobody is measuring one’s office presence”. The underlying motivation for the policy can be found in the Swedish legislation – if an employee spends 50% of time or more working from home, the employer is responsible for the equipment and ergonomics of the home office. Therefore, the policies like in Case B may be falsely understood as unwillingness to take the responsibility for the employees’ well-being while they are working from home.

Due to the half-empty offices, the free parking deal was cancelled, and the office space will soon be reduced. More costly commute to work in Case B is a larger problem than in Case A, since most workers commute to work by car. Further, in another company location in Sweden the downsizing will result in closing down an office building, relocating the units into other buildings and having limited seating for the employees. This might be problematic, since the office presence seem to be increasing. As a manager explains:

“We have seen an increase in office presence in the last months. [In four weeks] it went from around 34% to about 47% […] We can feel this in our parking area”.

The increase in the office presence is probably the result of numerous activities taken by the management and the employees themselves. Teams were said to organize team breakfasts, while the management initiatives include few weeks long “return to the office” events, onsite seminars, gatherings and afterworks.

4.4 Remote Work Policy in Case C

Case C is a financial services company headquartered in Norway, which operates in the Nordic markets. The company employs more than 2,000 people in total. During the pandemic employees in the bank reported many benefits of working from home [4], including an increased ability to focus, fewer distractions, increased flexibility to organize one’s work hours, less time spent on commuting, as well as more efficient and shorter meetings. Subsequently, many wanted to continue working from home after the pandemic. To satisfy the individual needs and maintain low retention the company introduced a very flexible work policy with only one exception – fully remote is not an option. Further, the policy minimized business travel (to meet the company sustainability goals), which was also used as one motivation for why not to allow employees to live on a far distance.

After reopening of the offices, employees started returning. The management discussed whether to introduce rules for mandatory office days. However, it was decided against the centralized regulation because different tasks have different requirements and a work unit (team, group, department) has much more insights for such decisions. As an HR manager explains:

“We need to understand that different employees and functions have different needs! […]One must also not misunderstand the approach as an anarchy where everyone has to decide for themselves. […] Our strategy as such we call Team-based flexibility with office as the core.”

The company management does not believe in a one-size-fits-all or that there is one, lasting solution that a team can have. The need for regular discussions is emphasized similarly to the way the goals, processes and tools are discussed on a regular basis. Albeit, achieving an agreement in teams with diverse preferences for onsite/remote work is not an easy task. The company is currently working towards understanding how to balance the needs of the individual vs the team vs the company, and how to account for the changes in the context, for example, when a team onboards a new member. The HR manager continued:

“We know that we have highly educated employees who are responsible for complex processes and solutions. Our social mission is, among other things, to ensure that our customers have financial security and freedom. With this as a backdrop, we believe it is unwise to use too many rules and policies to try to manage the organization.”

Case C strategy is not to force employees back but to offer them attractive conditions to return, including better lunch, office-based events on Tuesdays, afterwork events, art classes and sport activities. Further, as the company became aware of the importance of uninterrupted work, they rebuild the offices introducing noise cancelling textures, furniture and walls, and created several quiet zones.

5 Concluding Discussion

In this paper, we studied the institutionalized degree of office/remote work in three Nordic companies, and the actions and changes in the office implemented after the pandemic and how these support the intensions. See the summary of our results Table 3.

Our findings suggest that the studied companies have similar intentions, but different approaches to regulating office presence. All three companies believe in the importance of office collaboration and express the emphasis on the office similarly (Office as “The main place of work” in Case A, “The center of innovation, learning and driving the culture” in Case B, and “The core” and “The base” in Case C). Yet, while Case A and B have introduced minimum demands on the office presence similarly to such tech giants as Apple, Amazon, and Twitter, Case C only states that working fully remote is not an option. Ironically, the company with the most flexible policy seem to have succeeded to attract more people back. Our findings suggest that one reason for this is related to the corporate actions that “lure” the workers back, and the way of doing hybrid must be adjusted to the people and tasks as also suggested in earlier research [6, 9]. The actions in all three companies largely overlap, with some differences in the impact on the workers (for example, cancelled free parking in Case B had a larger impact than in Case A), and some additional amenities in Case C.

In Table 3, we visualize the “messages” that employees in all three companies “receive” through the corporate policies, management announcements and the actions introduced by the companies, including workplace transformations and renovations, changes in the amenities and onsite events. It is evident, that no one company is fully consistent in their intentions. In the following, we list the discrepancies and competing interest that companies shall take into consideration to set informed priorities:

-

Discrepancy: Intention to increase office presence while cutting the workspace. Maintaining half-empty offices is not a cost-efficient strategy and many companies downsize their offices or onboard more people without increasing office capacity [11]. In doing so, some employees are destined to less convenient working (no personalized space, unpredictable seating) or shortage of work desks, which affects the office presence negatively. Important software development practices like pair programming have been found to suffer in such conditions [12] because developers are disturbing each other.

-

Discrepancy: Intention to increase office presence while removing free parking. Along with downsizing, many companies cancel free parking deals, resulting in the less convenient and more costly commute, which again may negatively affect office presence or employee satisfaction.

-

Competing interests: Intention to increase office presence while keeping the individual workers satisfied. These competing corporate and individual interests are hard to satisfy since many workers prefer to work increasingly remotely [1, 3, 6]. In our study, these competing interests often manifest in discrepancies in how management communicates the desired office presence (See “Announcements” in Table 1) and how it is formally regulated (See “Policies” in Table 1).

-

Competing interests: Intention to satisfy individual and team needs. Finally, the interests of the teams and individuals might not be aligned, especially when the team is composed of workers with different preferences for onsite/remote work. Our study shows that coming to an agreement about suitable flexible working rhythm in a team is not always an easy task, but promotion of team values and team-based decisions sets clear priorities.

We conclude that hybrid work is prone to inherent conflicts of interest between the individual employees (flexibility, individual productivity, and well-being), the teams (effective collaboration, spontaneous interaction) and the companies (profitability, quality of products and services, employee retention, attractiveness in the job market) that require attention when formulating the new work policies. One step towards understanding whether the intentions and actions are aligned is to perform a mapping based on the corporate strategy documents, announcements and revising the changes at the workplace, similar to the one offered in this study. Resolving the potential conflicts is not an easy task and requires a clear motivation behind the chosen work policy.

References

Smite, D., Moe, N.B., Hildrum, J., Gonzalez-Huerta, J., Mendez, D.: Work-from-home is here to stay: call for flexibility in post-pandemic work policies. J. Syst. Softw. 195, 111552 (2023)

Smite, D., et al.: Jyväskylä. Finland 2022, 252–261 (2022)

Barrero, J.M., Bloom, N., Davis, S.J.: Let me work from home, or I will find another job. In: Working Paper, University of Chicago, pp. 2021–2087 (2021)

Smite, D., Tkalich, A., Moe, N.B., Papatheocharous, E., Klotins, E., Buvik, M.P.: Changes in perceived productivity of software engineers during COVID-19 pandemic: the voice of evidence. J. Syst. Softw. 186, 111197 (2022)

Smite, D., Christensen, E.L., Tell, P., Russo, D.: The future workplace: characterizing the spectrum of hybrid work arrangements for software teams. IEEE Softw. 40, 34–41 (2022)

Conboy, K., Moe, N.B., Stray, V., Gundelsby, J.H.: The future of hybrid software development: challenging current assumptions. IEEE Softw. 40(02), 26–33 (2023)

Yang, L., et al.: The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nat. Human Behav. 6(1), 43–54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

de Souza Santos, R.E., Ralph, P.. Practices to Improve Teamwork in Software Development During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Ethnographic Study. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Cooperative and Human Aspects of Software Engineering, 2022, pp. 81–85

Mens, T., Cataldo, M., Damian, D.: The social developer: the future of software development [guest editors’ introduction]. IEEE Softw. 36(1), 11–14 (2019)

Berntzen, M., Hoda, R., Moe, N.B., Stray, V.: A taxonomy of inter-team coordination mechanisms in large-scale agile. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 49(2), 699–718 (2022)

Moe, N.B., Stray, V., Smite, D., Mikalsen, M.: Attractive workplaces: what are engineers looking for? IEEE Softw. 40(5), 85–93 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2023.3276929

Tkalich, A., Moe, N.B., Andersen, N.H., Stray, V., Barbala, A.M.: Pair programming practiced in hybrid work. In: A Short Paper in the International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM) (2023)

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Research Council of Norway through the 10xTeams project (grant 309344) and the Swedish Knowledge Foundation through the KK-Hög project WorkFlex (grant 2022/0047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Smite, D., Moe, N.B. (2024). Defining a Remote Work Policy: Aligning Actions and Intentions. In: Kruchten, P., Gregory, P. (eds) Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programming – Workshops. XP XP 2022 2023. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, vol 489. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48550-3_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48550-3_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-48549-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-48550-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)