Abstract

Using interviews with various families and mediators/lawyers involved in three types of out-of-court procedures in England and Wales, this contribution assesses, first, to what extent the interests of the child are in focus in such procedures. And second, whether in certain types of cases, the interests of the child are better protected by means of in-court procedures. The authors find that, while out-of-court procedures are generally child-focused, it is less common that they are child-inclusive or that the clear voice of the child is represented in the adult decision-making. Further, in the out-of-court context, ‘child welfare’ tends to be understood in terms of ongoing contact with both parents and co-parenting. Consequently, the protection of children from an abusive parent can be under-emphasized. In some instances, concerns about children tend to be overshadowed by the financial dispute. Additionally, given there is growing evidence that many children would like to be consulted in out-of-court family dispute resolution, and that (where it is appropriate and safe) this can be a positive influence on their wellbeing. Consideration is given to how current practice in family dispute resolution fits with the rights expressed in Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In conclusion, the authors highlight a need for distinguishing between different types of conflicts and adjusting procedures accordingly. For example, in high-conflict cases and/or those involving issues of child safety, the interests of the child might be better protected in court, rather than through out-of-court dispute resolution. Whereas in other situations, barriers to hearing the child’s voice out-of-court must be overcome.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Children’s rights

- Safeguarding issues

- Child-inclusive mediation

- Family dispute resolution research findings

- Family justice policy and reform

6.1 Introduction

As noted in the introduction to this volume, parental conflicts concerning children often lead to major challenges that can jeopardize the wellbeing of all involved.Footnote 1 While parents have traditionally turned to the courts to resolve such conflicts, Barton argues that:

The demands of child custody issues are so profound that we in the law may be required to transcend our normal understanding of a “legal procedure”. Custody arrangements may require lawyers to acknowledge and incorporate different ways of thinking and speaking about rights, relationships, and social environments.Footnote 2

Yet different ways of approaching custody issues must also be subject to scrutiny to determine their impact on children and parents.

Against this background, in England and Wales—where policymakers have used changes to legal aid to restrict access to lawyers and encourage people to resolve custody and visitationFootnote 3 conflicts outside the court system through mediation—research into these developments can provide some important insights. These changes stemmed from a radical, neoliberal shift in thinking about family justice, driven by state cost-saving imperatives. Yet the rhetoric which accompanied them extolled the virtues of mediation (compared with court processes), as a means of reducing parental conflict and improving outcomes for children. This was despite a lack of evidence about experiences of mediation or about outcomes achieved when cases are diverted away from court into mediation. Neither was there any serious consideration of what other out-of-court alternatives may offer or what wider support such as counselling might be needed. Nonetheless, the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 was implemented in April 2013, preserving legal aid for family mediation, but withdrawing it for both legal advice and court representation in all custody and visitation cases—except in cases where there was evidence of domestic abuse. This means that only those who can afford to pay can now seek legal advice, and those who cannot, must either mediate (assuming both parties agree to this) or represent themselves in court. As will be discussed, this attempt to remove lawyers and courts from the resolution of parental conflicts concerning children, and to replace them with mediation, has had unintended consequences; many of which risk negatively affecting children’s agency and best interests in matters involving them when their parents separate.

In this chapter, we will first draw on research evidence examining whether the interests of the child are of primary concern and the voice of the child is heard when out-of-court dispute resolution processes are used by separating parents. Second, we will discuss whether, in certain types of cases, the interests of the child are better protected by means of in-court procedures, where the guiding legal principle specifically states that the welfare of the child is paramount.Footnote 4 Then we will examine growing evidence that many children would like to be consulted in out-of-court family dispute resolution, and evidence that consultation with children involved in court processes is inadequate. In both instances, we reflect on whether current practice corresponds with the rights expressed in Article 12 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and what might be done to improve recognition of those rights.

6.2 The Studies

The chapter uses research evidence from three empirical studies undertaken by the authors in England and Wales. The first, Mapping Paths to Family JusticeFootnote 5 (Mapping), was conducted between 2011 and 2014 and was a major study on awareness and experiences of out-of-court family dispute resolution processes. Two smaller follow-up studies focused on how to improve these processes, and in particular mediation, in the light of the Mapping findings: Creating Paths to Family Justice (Creating) (2015–2016) and the Healthy Relationship Transitions (HeaRT) project (2019–2022). Both of the smaller studies, unlike Mapping, collected data from young people whose parents had separated.

6.2.1 Project Design and Methods

The relevant Mapping research objectives were:

-

1.

To provide an up-to-date picture of awareness and experiences of three main out-of-court family dispute resolution processes, namely:

-

Family mediation, where both adult parties attempt to resolve issues, including arrangements for their children, with the assistance of a family mediator.

-

Solicitor negotiation, in which the parties’ lawyers engage in a process of correspondence and discussion to broker a solution of the issues on behalf of their clients without going to court.

-

Collaborative law, where each party is represented by their own lawyer and negotiations are conducted face to face in four-way, non-adversarial ‘collaborative’ meetings between the parties and their lawyers, all committed in a formal contract to reaching agreement without going to court. If no agreement is reached, the parties must instruct new lawyers if they want representation in court.

-

-

2.

To map which out-of-court processes suited which types of cases and parties.

-

3.

To consider how well children’s best interests were served and how, if at all, their voices were heard in out-of-court processes concerning child arrangements.

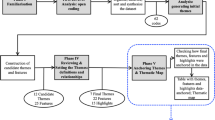

This study is comprised of three interlinking phases.Footnote 6 First, a quantitative, nationally representative survey (n = 2974) was conducted, using a structured questionnaire to gauge public awareness of out-of-court dispute resolution options and to collect experiences from the divorced and separated populations who had used out-of-court processes between 1996 and 2011. Second, we used qualitative, semi-structured interviews to gain insights and experiences of the out-of-court processes from 40 practitioners (lawyers, mediators, or both), and also from 95 divorced/separated men (n = 45) and women (n = 50). Our third phase focused on gaining a more in-depth understanding through recording and analysing the transcripts of 13 complete, out-of-court processes relating to children and/or financial disputes. These included five mediation processes, three collaborative law processes, and five first interviews between solicitor and client in which the aim was to reach agreement without going to court.

Relevant findings included:

-

Relatively high levels of satisfaction (over 66%) with all three processes among those interviewed, but different out-of-court processes have different strengths which suit different parties and cases.

-

Parties must be emotionally ready for any out-of-court process to be successful, particularly mediation, because parties cannot rely on a lawyer for support in the process.

-

The main reasons people chose not to mediate were fear of their partner and refusal of their partner to engage.

-

Screening for domestic violence in mediation was not consistent and often ineffective.

-

The out-of-court procedures all aimed to be child-focused, but the recorded sessions revealed a substantial risk that adult interests could predominate over those of the children.

-

Although mediation could extend to be child-inclusive (that is, where a child, with parental agreement, sees the mediator at a separate meeting and their views are fed back sensitively to the parents), this option was rarely used in practice. We found this was due to both parental and mediator reluctance.

CreatingFootnote 7 involved five themed workshops conducted with policymakers, practitioners, and professionals. It followed various practical aspects of addressing the Mapping findings, in light of the new policy emphasis on resolving parental disputes through mediation in most circumstances. The final workshop in 2016, focused on children’s voices. Participants included five young people aged 9–20, who were members of the Family Justice Young People’s Board (FJYPB) and who had themselves experienced conflict between their parents about their post-separation child arrangements. Through their work with the FJYPB (which campaigns to improve family justice for childrenFootnote 8), these participants were also familiar with other young people’s accounts of their experiences. The objective was to understand what information young people needed about in-court and out-of-court procedures, and whether and how children’s views could be included in both settings. The conclusion was that a trusted website was needed that covers a range of issues relevant to young people, including parental separation, and that technology should be better harnessed to help guide young people through disputes, including a means for children to contact professionals involved in their parents’ case.

The HeaRT projectFootnote 9 considered experiences of child-inclusive mediation (CIM), including the role it might play in promoting paths to better mental health and wellbeing for young people whose parents separate. Here, we interviewed 10 relationship professionals, 20 CIM-trained mediators, 12 parents, and 20 young people who had participated in CIM. We also ran four focus groups (one for those aged 11–15, one for those aged 16+, and two with more mixed age groups) with a total of 22 FJYPB members. We then ran two panels with a wider group of FJYPB members, plus young people from schools and community groups (n = 24). The purpose was to gauge their views on learning within the school curriculum about the legal processes surrounding parental separation, as well as whether children feel they should have a voice within such processes. We found strong support for both more child-inclusive processes and more education.

6.3 Theory and Practice With Children’s Voices Out-of-Court

The Mapping study exposed how the focus on children’s welfare was handled by the practitioners and parents in out-of-court dispute resolution processes. We found little direct child consultation was taking place, despite mediators’ high uptake of formal training and accreditation to conduct CIM.Footnote 10

6.3.1 Child-Focused Processes

The practitioners in the Mapping study all stressed that the child’s best interests were ‘fundamental’ to out-of-court family dispute resolution. It should be noted that while Section 1(1) Children Act 1989 makes the child’s welfare paramount in decisions made by the court, this does not extend to out-of-court dispute resolution processes. However, though the professional codes of conduct governing lawyer and mediator practice are not directly enforceable as a matter of law, they do require these professionals to promote the child’s welfare as the paramount consideration.Footnote 11 This has helped to make child-focus the norm in all processes. The opening to one of our recorded mediation sessions typifies the approach:

What we are looking for here is a solution that has [child]’s best interests at heart rather than a solution that is specifically geared to either one of you, because that’s the most important isn’t it? Mediation 209(1)

Most parties we interviewed also agreed that their practitioner had focused on the child’s best interests. One party, Kathy,Footnote 12 when asked whether the mediator succeeded in getting her and her ex-partner both focused on their child’s wellbeing, confirmed:

Yeah, she did. It were obvious that her main goal was to – I mean, she’d never met my daughter, but her main goal were to get something sorted between the pair of us for her. Kathy, Mediation

Good, child-focused practice where mediators were skilled at reframing issues around children was also noted:

One of my husband’s objectives was to spend as much time with the children as possible and so the mediator said, “Well, why don’t we phrase it as ‘to be able to build meaningful relationships with the children?’” Tracy, Mediation

Because you have both accepted that you do want [child] to have a relationship with his dad, so how can we reintroduce contact in a way that would be sensitive for [child]? Mediation 209(1)

However, while the separation of adults and children’s needs is encouraged as good practice, children’s active involvement in non-court processes is not mandatory—either in law or as a matter of professional conduct.Footnote 13 Thus we found a tendency (also observed within court proceedingsFootnote 14) for children’s voices to be channelled through parental perspectives. Although all processes started child-focused, we found this was often difficult to maintain in competition with the drive for agreement between the adults, so that the interests and voices of young people risked getting lost.Footnote 15 As one mother put it:

It was more “this is what [ex-partner] wants to do, this is what Rebecca wants to do, can you come to an arrangement of what you want?” rather than “this is what is best for the children.” Rebecca, Mediation

Time constraints and complexity of other issues could also mean the focus on children could get overlooked in mediation:

[The mediator] decided that we had a choice between discussing our finances or discussing about the child, and we discussed finances. Sonia, Mediation

The notion of ‘child-focus’ could also be observed superficially, as parents often used a child-welfare discourse to justify their own position, rather than really thinking about what was best for the child. For example, some fathers thought children had the right to spend half their time with their father, whereas some mothers thought that children needed to be mostly with their mothers—without either parent considering what their child wanted.

Indeed, some parents felt it was inappropriate to consult their children, preferring to shield them from the conflict situation as far as possible. Seth, a father of nine-year-old twins, told them he was moving out only two weeks before it happened, saying:

So at the time of the mediation they didn’t know anything about it, but of course we wanted to protect the children from all that as much as possible.

There was certainly no accepted view that children should be consulted, which raises the issue of how well non-court processes accord with children’s rights under Article 12 CRC in England and Wales.Footnote 16

There was, however, some evidence that where parents did consult their children, this could break the deadlock. This worked for Sheila, who ended her collaborative law process because she thought the proposed arrangements would not work well for their children:

I actually spoke to the kids … and I said, “Look, part of the reason things were difficult was because we were about to make these new arrangements. What do you think?” And they said, “Fine, we’ll try it”.

This confirmed other researchFootnote 17 that, as well as being beneficial for the child, going beyond a child-focused approach and directly consulting children may be an effective way of dealing with cases where the parents’ views on what is best for the children are fixed and incompatible.

6.3.2 Child-Inclusive Practices

CIM involves the child being directly consulted by the mediator, who feeds their views back to the parents at a separate mediation session, in a way agreed between the child and the mediator. In theory, this is available to all who mediate child arrangements in England and Wales. Yet children are likely to discover this option only if their parents tell them. Few of the Mapping study practitioners offered CIM routinely, despite two-thirds of the mediators we interviewed (20 of 31) being qualified to undertake it. We found a surprising lack of practitioner confidence. While many felt it was a good idea, only two practised direct consultation frequently. Around half had only ever conducted one or two cases and some had not taken a single case.

A minority of mediators were very pro-direct consultation. One such example was Molly Turner:

I am very much about involving the voice of the child, you know. All the research that I have read … tells me the same common factor; children don’t feel heard, they feel lied to and they feel betrayed by the parents because they haven’t been told the truth about things … and … the decision making quite often ignores the children’s wishes.

However, others found that the practical objections to it, such as lack of parental consent or the additional cost, inadequately covered by legal aid, most often prevailed:

We can offer it in very unusual circumstances, but it is very rare. Melanie Illingworth

In the study, we found very few parents who had consented to CIM. One father, who had successfully used the method to resolve an entrenched dispute about which school his daughter should attend, still had reservations:

I think it puts [children] in a very difficult position … I think it has to be managed so very carefully. (Ernest, CIM)

Thus, while we did not interview children in the Mapping study, this led us to reflect further on how they could be better consulted or involved in decision-making out-of-court, in line with their ostensible CRC rights, and whether the desire to protect children from consultation should be challenged. We concluded that the issue of children’s voice was an area where further research was certainly needed.

6.4 Safeguarding Children and the Role of the Court

Despite the policy emphasis on mediation, it is clear that out-of-court family dispute resolution processes are not always appropriate. They can pose a risk to the safety of both adult participants and children affected by arrangements that are ‘agreed’ as a result of intimidation, coercion, or continuing control by an abusive parent. Social services have no involvement in cases that do not go to court in England and Wales, and no role in assessing the suitability of agreements about child arrangements made out-of-court. As noted in the description of the project design in the Introduction, part of the objective of the Mapping study was to identify which cases and parties were suitable for different dispute resolution processes. We concluded, where there is a significant psychological disparity between the parties, a significant power imbalance between them, or where one party is vulnerable in some way; that party and their children needed the protection at least of a lawyer. In many of these cases, the more powerful party will seek to exploit this imbalance and be unwilling to compromise or offer a fair and just resolution of the dispute, with the result that court proceedings become necessary. Furthermore, with the major cuts to legal aid in 2013, legal representation is now out of reach for many people with family disputes, making recourse to the protection of the court the only safe option in such cases.

One finding of concern in the Mapping study, was that screening for domestic abuse and other vulnerabilities that would make mediation unsuitable was not done consistently or effectively. We interviewed a number of women who said they had not been asked about any history of abuse in their relationship, had not felt able to disclose their fear of the other party to the mediator—due to the circumstances in which screening took place—or had been pushed into attempting mediation despite a known history of abuse. In these cases, the failure of screening led to traumatic experiences of mediation and unfair agreements which exposed them and their children to the ongoing risk of abuse.

Direct consultation with children might seem even more important in these cases, given that children’s safety is at stake. Yet this was not a consideration raised in our interviews with practitioners in Mapping, many of whom appeared to adhere to the (false) belief that violence between adults would have no or minimal effect on the children, and that an abusive partner could still be a good parent. Consultation with children could operate to displace these assumptions. In Tilda’s case, for example, there had been threats of violence undisclosed due to poor screening, yet sufficient concerns about her ex’s forceful attitude in the mediation intake procedure resulted in the appointment of two mediators to co-mediate the case, rather than the usual one. Despite this, there was no suggestion by the mediators that the children’s views on a proposed agreement for equal shared care should be considered. Nor did any practitioners in our interview sample raise children’s perspectives as a potentially important consideration in cases where there was a history of domestic abuse.

By contrast, in court proceedings in England and Wales, there is a dedicated agency—Cafcass (the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service)—whose role is to promote and safeguard children’s welfare. In all cases in which a court application is made concerning post-separation child arrangements, Cafcass undertakes initial safeguarding checks to discover whether the family is known to the police or local children’s social services. They also conduct a telephone interview with both parents, inviting them to raise any concerns about their children’s welfare. The results of these checks then inform the court throughout the process. It is notable, for example, that a recent pilot study by Cafcass to explore the scope for initial diversion from court, to support parents to agree on arrangements rather than continuing with court proceedings, found that 80–86% of cases raised such serious safeguarding issues that they were not suitable for diversion.Footnote 18

However, while the child focus of the court process may be clearer, direct inclusion of children’s voices remains limited. In the majority of cases, the court encourages and assists parents to settle matters between themselves, with no reference to the views of the children. It is only if cases reach a more advanced stage of proceedings that Cafcass may be ordered to provide a report that includes the children’s wishes and feelings. And it is only in the most serious cases that the court will appoint a guardian to provide separate representation for the child. Cafcass data indicates that it provides reports in only around one-third of cases, and a guardian is appointed in fewer than 10% of cases.Footnote 19 It is also very rare for children to give evidence in family courts and uncommon for them to meet with the judge in their case.Footnote 20 Thus, while the court process may pay more direct attention to children’s welfare, it is not necessarily better at making good their Article 12 rights.

6.5 Facilitating Children’s Voices—The Evolving Picture

Since the Mapping study, the mediation community and its regulators have made changes encouraging greater uptake of CIM where appropriate, while ensuring children’s safety and wellbeing.Footnote 21 This is arguably paving the way for children’s voices to be better heard in mediation: according to surveys conducted by the Family Mediation Council, the use of CIM increased from 14% of cases in 2017 to 26% in 2019.Footnote 22

Other research indicates that consultation with children is associated with children being more satisfied with arrangements,Footnote 23 arrangements lasting longer, better father-child relationships, and more cooperative parenting.Footnote 24 However, we wanted to capture children’s perspectives on whether the right to be consulted on matters affecting them on parental separation would be welcomed. At the Creating workshopFootnote 25 in 2016 with the FJYPB members, these participants flagged difficulties encountered by children seeking information about the separation process. They emphasized how unsupported children typically were when parents separate, and unanimously agreed that, as a matter of principle, children of appropriate age should have the right to be consulted, irrespective of whether parents resolved issues in or out-of-court. The participants took the view that consultation should be the child’s choice, with children being part of the conversation rather than simply being asked to choose between their parents’ preferred options. In the further HeaRT study in 2020, during the focus groups, the wider group of FJYPB participants also strongly argued that children should be actively involved in decision-making:

I think the child … should be involved as much as they can just because it’s their life that’s being decided about … you should [not] … let your parents decide … what’s going to happen in your life when it’s not their life that they are making decisions for. Max

Several young people interviewed in the HeaRT study were pragmatic, appreciating how CIM helped to ‘get stuff sorted’ (Alex). Most spoke of benefits outside of dispute resolution. Freddy liked that his parents cared about his opinion. Christina felt that being consulted had validated her feelings. Several spoke of anxieties lessened by having a clearer understanding of the process. Many welcomed the opportunity to discuss with an empathetic third party, things they felt unable to raise with their parents, which Ellie noted gave children ‘a sense that somebody is there for them, that they have somebody … to … talk to’. Alfie felt the process had improved communication with his parents:

It opened me a lot more and made me a lot more confident to speak to my [parents] about things, which just made a lot of stuff much, much easier and took a lot of stress off my chest.

Most felt empowered by the process, as summed up by Anna:

[CIM gives young people] … a voice … they are being respected … it’s actually quite cathartic for children to be able to kind of explain what's going on to someone and someone to listen to them.

One of the key features of CIM, and children’s responses to it, is that children’s voices are heard and validated in a non-judgemental way. More recent research suggests that regrettably, this may not be the case when children are consulted as part of court proceedings. In 2019, the Ministry of Justice established an expert panel and issued a public call for evidence on how effectively family courts protect children and adult victims of domestic abuse, child abuse, and other serious offences from harm in family-law cases. The call received over 1,000 submissions, a substantial majority of them from mothers who were victims of domestic abuse and who had attempted to protect their children from abuse through the court process. In addition, there were a small number of responses from young people who had been the subject of court proceedings as children. The experiences recounted in these submissions pointed to serious failings in the court process. In particular, the panel concluded that ‘The weight of evidence from both research and submissions suggests that too often the voices of children go unheard in the court process or are muted in various ways’.Footnote 26

Even in those cases where children were consulted by Cafcass for the purposes of reporting their wishes and feelings to the court, the panel found extensive evidence of ‘selective listening’, whereby children who said they wanted to have contact with the parent they did not live with were supported, but children who said they did not want to have contact were ignored, disregarded, dismissed, or misrepresented. Children opposed to contact were often considered to be simply reflecting the views of the parent with whom they were living, or to have been brainwashed by that parent or ‘alienated’ by them from the non-resident parent. Furthermore, the process by which children’s views were elicited was also criticized. Children were not given sufficient time to build a relationship of trust with the Cafcass officer or guardian in which they felt safe to disclose their fears. These concerns were compounded for children with learning difficulties or other special needs who were not effectively supported to enable them to communicate their views. At the same time, trusted adults in whom children had confided were either not interviewed or were similarly dismissed. Children found the failure to listen to them (and the resulting court orders which left them with contact arrangements in which they did not feel safe) to be profoundly disempowering.Footnote 27 The report concluded that more should be done to accord children the opportunity to be heard in proceedings in accordance with their Article 12 rights.Footnote 28 It recommended substantial reforms to the court process to, among other things, incorporate consultation with children of sufficient age in all cases. Systematic consultation would not only have procedural benefits in including children in decision-making in matters affecting them, but also, should have substantive benefits in improving the protection offered by the courts against future abuse and the risk of harm to the child.

6.6 Conclusion

In the context of England and Wales, mediation is seen as a ‘good’ means of dispute resolution: it is non-adversarial, reduces conflict, and restores autonomy to the parties. It is contrasted with court, which is seen as inherently ‘bad’ and likely to inflame conflict between parents, with lawyers being regarded similarly. In our view, this dichotomy between court (and lawyers) and out-of-court processes is far too simplistic. While we cannot say that one process is always better for children than the other, in some circumstance one or the other will be more appropriate, and we suggest that the focus should be on good practices within ANY process. Above all, there is a need for effective screening to distinguish different types of conflicts and adjust procedures or divert people to the right process for their situation.Footnote 29 In all procedures, however, whether in or out-of-court, barriers to hearing the child’s voice must be overcome.

The findings of our Mapping research indicate that, while out-of-court family dispute resolution processes attempt to focus on children’s welfare, that focus can be lost in the details of the adult dispute. Direct consultation with children in out-of-court processes would help to maintain focus on the child’s interests and preferences on matters directly affecting them, but the Mapping research found that this occurred only rarely, revealing a clear gap between the theory and the practice.

In the mediation context, some of the practical and attitudinal barriers to hearing the child’s voice are now being addressed,Footnote 30 and although CIM remains a minority practice, enthusiasm for it has grown. Its use is increasing and our subsequent Creating and HeaRT research suggests this is in accordance with children’s desires to be included in conversations about the custody and visitation arrangements their parents make post-separation. This also resonates with other research findings on this issue in Norway.Footnote 31

The Mapping research also identified an important role for the court in protecting those vulnerable to abuse, coercion, and control. In such cases, the process and outcomes of mediation can be unsafe and unsatisfactory, while the court is required by law to make the child’s welfare its paramount consideration and to consider children’s wishes and feelings in its decision-making. Particularly in the absence of lawyers after the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, court proceedings appear to be more appropriate than mediation in such cases. Recent evidence suggests, however, that the safeguarding and protection that should be offered by the court is not being effectively delivered in practice. Here, more progress must be made in both consulting children and listening to what they say—but the government’s commitment to implementing the expert panel’s recommendations,Footnote 32 including those on more consistent attention to the voice of the child, gives some hope for future improvement.

Lack of consultation with children whose parents separate, about the arrangements being made for them—either in or out-of-court—would seem to infringe Article 12 CRC, despite the UK having ratified the Convention. While Scotland and Wales are in the process of adopting the CRC into domestic law,Footnote 33 England currently has no such plans; thus, children’s rights—including the right to express their views freely in matters affecting them—are currently unenforceable. Although improvements are now being seen in out-of-court and in-court procedures, this lack of enforceability must continue to be challenged.

Notes

- 1.

See Anna Kaldal, Agnes Hellner and Titti Mattsson, ‘Introduction: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problemsin Custody Disputes’ in Anna Kaldal, Agnes Hellner and Titti Mattsson (eds), Children in Custody Disputes: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problems (Palgrave 2023).

- 2.

See Thomas D Barton, ‘Challenges When Family Conflicts Meet the Law—A Proactive Approach’ in Anna Kaldal, Agnes Hellner and Titti Mattsson (eds), Children in Custody Disputes: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problems (Palgrave 2023).

- 3.

These terms have been replaced by the deliberately more neutral and collective term ‘child arrangements’ in the law of England and Wales. See Section 8 Children Act 1989.

- 4.

Children Act 1989 Section 1.

- 5.

This was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (grant no ES/1031812/1). See further, Anne Barlow, Rosemary Hunter, Janet Smithson and Jan Ewing, Mapping Paths to Family Justice: Resolving Family Disputes in Neoliberal Times (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

- 6.

Research Ethics Approval was obtained from the University of Exeter Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee.

- 7.

For further details, see Anne Barlow, Jan Ewing, Rosemary Hunter and Janet Smithson, Creating Paths to Family Justice: Briefing Paper and Report on Key Finding (University of Exeter, 2017). The project was funded by the ESRC Impact Accelerator Account. Research Ethics Approval for the workshop was obtained from the University of Exeter Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee.

- 8.

This is a formal consultative group of the Family Justice Board and is supported by the Children and Families Court Advisory Service (Cafcass).

- 9.

The Wellcome Centre on Cultures and Environments of Health-funded Healthy Relationships Beacon Project: Healthy Relationship Education (HeaRE) and Healthy Relationship Transitions (HeaRT) (2019–2022) led by Anne Barlow. Research Ethics Approval for the HeaRT project was obtained from the University of Exeter Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Grant ref: 203109/Z/16/Z). See further, Anne Barlow, Jan Ewing, Tamsin Newlove-Delgado and Simon Benham-Clarke, Transforming Relationships and Relationship Transitions with and for the Next Generation: Report and Key Findings (University of Exeter 2022).

- 10.

For a fuller discussion see Jan Ewing, Rosemary Hunter, Anne Barlow and Janet Smithson, ‘Children’s Voices: Centre-Stage or Side-lined in Out-of-Court Dispute Resolution in England and Wales?’ (2015) 27(1) Child and Family Law Quarterly, 43–61.

- 11.

Family Law Protocol, 3rd ed, 2010, para. 1.5.1; see also Family Mediation Council Code of Practice, 2018 para. 5.7.1: ‘At all times mediators must have special regard to the welfare of any children of the family’. Failure to observe the codes and protocols can found a complaint of professional misconduct but these matters are handled by the professional bodies themselves, not as a matter of law.

- 12.

All participant names have been pseudonymized to preserve anonymity.

- 13.

Family Law Protocol (n 11); Family Mediation Council Code of Practice (n 11).

- 14.

See Helen Stalford and Kathryn Hollingsworth, ‘“This Case Is About You and Your Future”: Towards Judgments for Children’ (2020) 83(5) MLR 1030–1058, who talk of children’s voices being “represented by proxy, adult-filtered accounts” in court.

- 15.

See further, Janet Smithson, Anne Barlow, Rosemary Hunter and Jan Ewing, ‘The “Child’s Best Interests” as an Argumentative Resource in Family Mediation Sessions’ (2015) 17(4) Discourse Studies 1–15.

- 16.

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Article 12: ‘States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child’.

- 17.

Jennifer E McIntosh, Yvonne D Wells, Bruce M Smyth and Caroline Long, ‘Child-focused and Child-inclusive Divorce Mediation: Comparative Outcomes from a Prospective Study of Post-separation Adjustments’ (2008) 46(1) Family Court Review 105–124; Jennifer McIntosh, Bruce Smyth, Margaret Kelaher, Yvonne Wells and Caroline Long, ‘Post-separation Parenting Arrangements: Patterns of Developmental Outcomes. Studies of Two Risk Groups’ (2011) Family Matters No 86, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- 18.

Cafcass, ‘Support with Making Child Arrangements Programme: Six Month Pilot Evaluation Report’, 2019, unpublished, on file with authors.

- 19.

Cafcass annual reports, cited in, Rosemary Hunter, Mandy Burton and Liz Trinder, Assessing Risk of Harm to Children and Parents in Private Law Children Cases: Final Report (Ministry of Justice 2020) 69–70. See also, Claire Hargreaves, Uncovering Private Family Law: What Can The Data Tell Us About Children’s Participation? (Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, Report, 2022). https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/nfjo_report_private_law_child_participation_20220615_FINAL-1.pdf, accessed 10 May 2023.

- 20.

Hunter and others (n 19) 70.

- 21.

Following the Final Report of the Voice of the Child Dispute Resolution Advisory Group, 2015, The Family Mediation Council (FMC), which sets standards for mediation nationally, amended its ‘Standards Framework’ in 2018 to require all mediators to attend CIM awareness or update training and explain CIM to prospective clients.

- 22.

See FMC Survey 2017 https://www.familymediationcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Family-Mediation-Survey-Autumn-2017.pdf and FMC Survey, 2019 https://www.familymediationcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Family-Mediation-Survey-Autumn-2019-Results.pdf both accessed 25 February 2023.

- 23.

Ian Butler, Lesley Scanlan, Margaret Robinson, Gillian Douglas and Mervyn Murch, ‘Children’s Involvement in Their Parents’ Divorce: Implications for Practice’ (2002) 16(2) Children & Society 89–102.

- 24.

Janet Walker and Angela Lake-Carroll, in Report of the Family Mediation Task Force 2014.

- 25.

With eight young people aged 9–20 who had experienced the family justice system during parental separation, and other family justice stakeholders, as part of the Creating Paths to Family Justice follow-on study. See further, Barlow and others (n 7).

- 26.

Hunter and others (n 19) 67.

- 27.

Hunter and others (n 19) Chapter 6.

- 28.

Hunter and others (n 19) 176.

- 29.

This finding resonates with Singer’s view that ‘differentiated and family-specific services are required’.

In Anna Singer, “Out-of-court Custody Dispute Resolution in Sweden—A Journey Without Destination’ in Anna Kaldal, Agnes Hellner and Titti Mattsson (eds), Children in Custody Disputes: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problems (Palgrave 2023).

- 30.

See also, recommendations on how these should go further and be holistically approached in the Report of the Family Solutions Group, 2020 https://www.familysolutionsgroup.co.uk/, accessed 25 February 2023.

- 31.

See Thørnblad, R and A Strandbu, ‘The Involvement of Children in the Process of Mandatory Family Mediation’ in Anna Nylund and others, (eds) Nordic Mediation Research (Cham: Switzerland: Springer Open, 2018), 183–208. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-319-73019-6.pdf.

- 32.

Ministry of Justice, Assessing Risk of Harm to Children and Parents in Private Law Children Cases: Implementation Plan (2020). See also, Family Procedure Rules, Practice Direction 36Z, which sets out a new investigative procedure in custody and visitation cases, currently being piloted in two court areas, which includes a default of consultation with the child in every case.

- 33.

The Scottish parliament voted unanimously for the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill to become law in 2021 but was referred to the Supreme Court by the UK government which successfully challenged its constitutionality. See REFERENCE by the Attorney General and the Advocate General for Scotland - United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill [2021] UKSC 42. The Scottish government has announced the intention to reintroduce a revised Bill. See https://www.thenational.scot/news/19956835.uncrc-bill-come-back-holyrood-supreme-court-defeat/, accessed 10 May 2023. Wales-only legislation incorporated aspects of the CRC into Welsh domestic law through the Rights of Children and Young Persons (Wales) Measure 2011.

References

Barlow A, Ewing J, Hunter R and Smithson J, Creating Paths to Family Justice: Briefing Paper and Report on Key Finding (University of Exeter 2017).

Barlow A, Ewing J, Newlove-Delgado T and Benham-Clarke S, Transforming Relationships and Relationship Transitions with and for the next generation: Report and Key Findings (University of Exeter 2022).

Barton T, ‘Challenges When Family Conflicts Meet the Law—A Proactive Approach’ in Kaldal A, Hellner A and Mattsson T (eds), Children in Custody Disputes: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problems (Palgrave 2023) 169.

Butler I, Scanlan L, Robinson M, Douglas G and Murch M, ‘Children’s Involvement in Their Parents’ Divorce: Implications for Practice’ (2002) 16(2) Children & Society 89.

Cafcass, ‘Support with Making Child Arrangements Programme: Six Month Pilot Evaluation Report’ (2019) unpublished, on file with authors.

Ewing J, Hunter R, Barlow A and Smithson J, ‘Children’s Voices: Centre-Stage or Side-lined in Out-of-Court Dispute Resolution in England and Wales?’ (2015) 27(1) Child and Family Law Quarterly 43.

Family Mediation Council Survey, 2017 https://www.familymediationcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Family-Mediation-Survey-Autumn-2017.pdf accessed 25 February 2023.

Family Mediation Council Survey, 2019 https://www.familymediationcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Family-Mediation-Survey-Autumn-2019-Results.pdf accessed 25 February 2023.

Family Solutions Group, Report of the Family Solutions Group, 2020 https://www.familysolutionsgroup.co.uk/ accessed 25 February 2023.

Hargreaves C, Uncovering Private Family Law: What Can the Data Tell Us About Children’s Participation? (Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, Report 2022) https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/nfjo_report_private_law_child_participation_20220615_FINAL-1.pdf accessed 14 May 2023.

Hunter R, Burton M and Trinder L, Assessing Risk of Harm to Children and Parents in Private Law Children Cases: Final Report (Ministry of Justice 2020).

Kaldal A, Hellner A and Mattsson T, ‘Introduction: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problems in Custody Disputes’ in Kaldal A, Hellner A and Mattsson T (eds), Children in Custody Disputes: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problems (Palgrave 2023) 1.

McIntosh J, Smyth B, Kelaher M, Wells Y and Long C, ‘Post-separation parenting, Post-separation parenting arrangements: Patterns and developmental outcomes. Studies of two risk groups’ (2011) Family Matters No 86, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

McIntosh J E, Wells Y D, Smyth B M and Long C M, ‘Child-Focused and Child-inclusive Divorce Mediation: Comparative Outcomes from a Prospective Study of Post-separation Adjustments’ (2008) 46(1) Family Court Review 105.

Singer A, ‘Out-of-court Custody Dispute Resolution in Sweden—A Journey Without Destination’ in Kaldal A, Hellner A and Mattsson T (eds), Children in Custody Disputes: Matching Legal Proceedings to Problems (Palgrave 2023) 129.

Stalford H and Hollingsworth K, ‘“This Case Is About You and Your Future”: Towards Judgments for Children’ (2020) 83(5) Modern Law Review 1030.

Thørnblad R and Strandbu A, ‘The Involvement of Children in the Process of Mandatory Family Mediation’ in Anna Nylund et al (eds) Nordic Mediation Research (Springer 2018) 183.

Walker J and Lake-Carroll A, in Report of the Family Mediation Task Force (2014) https://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/family-mediation-task-force-report.pdf accessed 10 May 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barlow, A., Hunter, R., Ewing, J. (2024). Mapping Paths to Family Justice: Resolving Family Disputes Involving Children in Neoliberal Times. In: Kaldal, A., Hellner, A., Mattsson, T. (eds) Children in Custody Disputes. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46301-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46301-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-46300-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-46301-3

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)