Abstract

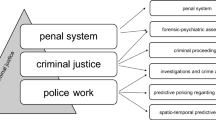

This chapter examines the use of algorithms in the realm of criminal justice (known as algorithmic criminal justice) and the potential paradigm shift towards pre-emption-driven decision-making. It contributes to debates about the increasing role of enabling technologies in understanding and responding to crime by turning the spotlight on criminal proceedings. It argues that, at first sight, algorithmic decision-making tools may present a strong potential to improve the operational efficiency of criminal justice authorities, but their use remains associated with hard-to-solve challenges, ranging from lack of transparency to questionable compatibility with core principles of substantive and procedural criminal law. Finally, it highlights the need for a balanced dialogue at the crossroads of technological novelty and (criminal) justice.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

The term ‘algorithm’ describes a ‘finite sequence of formal rules’ that makes it possible ‘to obtain a result from the initial input of information’: CEPEJ (2018), p. 69. An algorithm ‘may be part of an automated execution process and draw on models designed through machine learning’: Idem.

- 3.

- 4.

Završnik (2019), p. 2. For the purposes of this chapter, the term ‘algorithmic governance’ is understood as ‘a form of social ordering that relies on coordination between actors, is based on rules and incorporates particularly complex computer-based epistemic procedures’: Katzenbach and Ulbricht (2019), p. 2.

- 5.

- 6.

E.g., Aletras et al. (2016).

- 7.

- 8.

CEPEJ (2018), pp. 14, 17–18.

- 9.

Završnik (2019), p. 3.

- 10.

CEPEJ (2020).

- 11.

CEPEJ (2018).

- 12.

- 13.

- 14.

European Commission (EC) (2021) Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union legislative acts. COM (2021) 206 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0206. This manuscript was submitted for publication in 2021 and, thus, it does not take into account the European Parliament's negotiating position on the AI Act that was released only in June 2023 and marked the beginning of the trilogue negotiations. See European Parliament (2023).

- 15.

Loomis, 881 N.W.2d, para.755 (emphasis added).

- 16.

COMPAS is one of the most commonly used risk-assessment algorithms across the US. See Wisser (2019).

- 17.

Loomis, 881 N.W.2d, para.755; Wisser (2019), p. 1814.

- 18.

Loomis, 881 N.W.2d, para.757; Wisser (2019), p. 1814.

- 19.

Loomis, 881 N.W.2d, para.757 (emphasis added).

- 20.

Summarised by Wisser (2019), p. 1815.

- 21.

- 22.

Quattrocolo (2020), p. 131.

- 23.

Idem; cf. Greenstein (2021).

- 24.

Acknowledging the limits of this book chapter in terms of providing a comprehensive comparative analysis, the focus liese on European jurisdictions that follow the civil law tradition.

- 25.

Quattrocolo (2020), pp. 132–133.

- 26.

Ibid (2020), pp. 137–144.

- 27.

See ibid (2020), pp. 151–152.

- 28.

- 29.

See Lancaster, Lumb (2006).

- 30.

- 31.

- 32.

See Quattrocolo (2020), pp. 181–221.

- 33.

Cf. CEPEJ (2018), pp. 20–25.

- 34.

Cf. Greenstein (2021).

- 35.

- 36.

Melzer (2020), p. 148.

- 37.

- 38.

Melzer (2020), p. 148.

- 39.

- 40.

Cf. Holder (2014).

- 41.

See Papadimitrakis (2019).

- 42.

- 43.

- 44.

Greenstein (2021).

- 45.

FRA (2020), pp. 69–73.

- 46.

Završnik (2019), p. 7.

- 47.

- 48.

- 49.

- 50.

- 51.

- 52.

Kehl et al. (2017), p. 23.

- 53.

Starr (2014), p. 806.

- 54.

Wisser (2019), p. 1818.

- 55.

Mittelstadt et al. (2016), p. 4.

- 56.

Završnik (2019), p. 10.

- 57.

The term “language” may have to be interpreted in a broader way in the future, considering the potential inclusion of programming languages into the respective discourse.

- 58.

Quattrocolo (2020), p. 93.

- 59.

- 60.

- 61.

Cf. FRA (2020), p. 58, 77.

- 62.

Sachoulidou (2021).

- 63.

Wexler (2018), p. 1343.

- 64.

See ECtHR (2020), p. 31.

- 65.

Cf. FRA (2020), p. 76.

- 66.

- 67.

- 68.

Cf. Hannah-Moffat (2019).

- 69.

- 70.

Kehl et al. (2017), pp. 26–27.

- 71.

Završnik (2019), p. 5.

- 72.

Ibid, p.6.

- 73.

Kaiafa-Gbandi (2019).

- 74.

Digital Rights Ireland Ltd v Minister for Communications, Marine and Natural Resources and Others and Kärntner Landesregierung and Others, Joined Cases C-293/12 and C-594/12, CJEU, 8 April 2014, ECLI: ECLI:EU:C:2014:238. See also Privacy International v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs and Others, Case C-623/17, CJEU, 6 October 2020, ECLI:EU:C:2020:790; Quadrature du Net and Others v. Premier ministre and Others, Joined Cases C-511/18, C-512/18 and C-520/18, CJEU, 6 October 2020, ECLI: ECLI:EU:C:2020:791.

- 75.

CEPEJ (2018), pp. 8–13.

- 76.

While examining the challenges of prediction in the realm of criminal justice, Robinson (2018, pp. 154–174) identifies three core tensions formulated as follows: ‘What Matters Versus What the Data Measure’; ‘Current Goals Versus Historical Patterns’; and ‘Public Authority Versus Private Expertise’.

- 77.

- 78.

Završnik (2019), p. 9.

- 79.

Ibid, p.11.

- 80.

Idem.

- 81.

See Hildebrandt (2018).

- 82.

- 83.

Završnik (2019), p. 7.

- 84.

See Quattrocolo (2020), pp. 214–215.

- 85.

- 86.

Cf. CEPEJ (2018), p. 36.

- 87.

- 88.

See Hildebrandt (2019).

- 89.

As suggested in the Loomis v. Wisconsin case; cf. Wisser (2019), p. 1816.

- 90.

See Wisser (2019), p. 1829.

- 91.

Cf. ibid, pp.1827–1828; Ebersbach (2020), p. 36.

- 92.

- 93.

Loomis, 881 N.W.2d, para.760.

- 94.

Wisser (2019), p. 1831.

- 95.

Idem.

- 96.

Idem.

- 97.

- 98.

Cf. Završnik (2019), p. 8.

- 99.

EC (2019), p. 1 (emphasis added).

- 100.

Ibid, p. 2.

- 101.

CEPEJ (2018), p. 54.

- 102.

Cf. Završnik (2019), p. 16.

- 103.

- 104.

References

Aletras N et al (2016) Predicting judicial decisions of the European court of human rights: a natural language processing perspective. PeerJ Comput Sci 2(2):1–19. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.93

Barabas C et al (2018) Interventions over Predictions: Reframing the Ethical Debate for Actuarial Risk Assessment. Available via Cornell University. https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.08238

Council of Europe Ad Hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence (CAHAI) (2020) Feasibility Study on AI Legal Standards. https://rm.coe.int/cahai-2020-23-final-eng-feasibility-study-/1680a0c6da

Council of Europe European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) (2018) European Ethical Charter on the use of artificial intelligence in judicial systems and their environment. https://www.coe.int/en/web/cepej/cepej-european-ethical-charter-on-the-use-of-artificial-intelligence-ai-in-judicial-systems-and-their-environment

Council of Europe European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) (2020) Possible introduction of a mechanism for certifying artificial intelligence tools and services in the sphere of justice and the judiciary: Feasibility Study. https://rm.coe.int/feasability-study-en-cepej-2020-15/1680a0adf4

Dreyer S, Schmees J (2019) Künstliche Intelligenz als Richter? Wo keine Trainingsdaten, da kein Richter – Hindernisse, Risiken und Chancen der Automatisierung gerichtlicher Entscheidungen. Computer und Recht 35(11):758–764. https://doi.org/10.9785/cr-2019-351120

Ebersbach M (2020) Big Data, Algorithmen und Bewährungsentscheidungen. In: Momsen C, Schwarze M (eds) Strafrecht im Zeitalter von Digitalisierung und Datafizierung. pp 26–37. https://kripoz.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Ebersbach-Big-Data-Algorithmen-und-Bew%C3%A4hrungsentscheidungen.pdf

European Commission (EC) (2019) Building Trust in Human-Centric Artificial Intelligence. COM (2019) 168 final. EUR-Lex - 52019DC0168 - EL - EUR-Lex (europa.eu)

European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) (2020) Guide on Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Right to a fair trial [criminal limb]. https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/GuideArt6criminalENG.pdf

European Parliament (2023) Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 14 June 2023 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union legislative acts. COM (2021)0206 –C9-0146/2021– 2021/0106(COD), 14 June, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2023-0236_EN.html

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2020) Getting the future right. Artificial intelligence and fundamental rights. https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2020/artificial-intelligence-and-fundamental-rights

Fuster GG (2020) Artificial Intelligence and Law Enforcement. Impact on Fundamental Rights. Study requested by the LIBE Committee. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU(2020)656295

Galetta A (2013) The changing nature of the presumption of innocence in today’s surveillance societies: rewrite human rights or regulate the use of surveillance technologies? EJLT 4(2) https://ejlt.org/index.php/ejlt/article/view/221/377

Greengard S (2020) Algorithms in the Courtroom. Available via Communications of the ACM. https://cacm.acm.org/news/244263-algorithms-in-the-courtroom/fulltext

Greenstein S (2021) Preserving the rule of law in the era of artificial intelligence (AI). Artif Intell Law. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-021-09294-4

Hannah-Moffat K (2019) Algorithmic risk governance: big data analytics, race and information activism in criminal justice debates. Theor Criminol 23(4):453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480618763582

Hao K, Stray J (2019) Can you make AI fairer than a judge? Play our courtroom algorithm game. Available via MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/10/17/75285/ai-fairer-than-judge-criminal-risk-assessment-algorithm/

High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG) (2019a) Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI. https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/ai-alliance-consultation/guidelines#Top

High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG) (2019b) Policy and Investment Recommendations for Trustworthy AI. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/policy-and-investment-recommendations-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence

High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG) (2020) The Assessment List for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (ALTAI) for self-assessment. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/assessment-list-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence-altai-self-assessment

Hildebrandt M (2018) Preregistration of machine learning research design. In: Bayamlioglu E et al (eds) Being profiled: Cogitas ergo sum. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, pp 102–105

Hildebrandt M (2019) ‘Privacy as protection of the incomputable self’: from agnostic to agonistic machine learning. Theor Inq Law 19(1):83–121

Holder E (2014) Attorney General Eric Holder Speaks at the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers 57th Annual Meeting and 13th State Criminal Justice Network Conference. Available via the United States Department of Justice Official Website. https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-eric-holder-speaks-national-association-criminal-defense-lawyers-57th

Hulette D (2017) Patrolling the intersection of computers and people. Available via Princeton University. https://www.cs.princeton.edu/news/patrolling-intersection-computers-and-people

Kaiafa-Gbandi M (2019) Information exchange for the purpose of crime control: the EU paradigm for controlling terrorism – challenges of an ‘open’ system for collecting and exchanging personal data. Eur Crim Law Rev 2:141–174. https://doi.org/10.5771/2193-5505-2019-2-141

Katzenbach C, Ulbricht L (2019) Algorithmic governance. Internet. Pol Rev 8(4):1–18. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1424

Kehl D, Guo P, Kessler S (2017) Algorithms in the criminal justice system: assessing the use of risk assessments in sentencing. Responsive Communities Initiative, Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Harvard Law School. Available via Harvard Library. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/33746041

Lancaster E, Lumb J (2006) The assessment of risk in the National Probation Service of England and Wales. J Soc Work 6(3):275–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017306071176

Lorenso T (2020) Nutzung von Big Data und Algorithmus-basierter Datenanalyse in der Beweisführung zum Nachweis des Vorsatzes. In: Momsen C, Schwarze M (eds) Strafrecht im Zeitalter von Digitalisierung und Datafizierung. pp 15–25. https://kripoz.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Lorenso-Nutzung-von-Biig-Data-und-Algorithmus-basierter-Datenanalyse-in-der-Beweisf%C3%BChrung-zum-Nachweis-des-Vorsatzes.pdf

Marx G (2021) Introduction: the ayes have it – should they? Police body-worn cameras. In: Newell BC (ed) Surveillance, privacy, and accountability. Routledge, London, pp 24–51

Meijer A, Wessels M (2019) Predictive policing: review of benefits and drawbacks. Int J Public Adm 42(12):1031–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664

Melzer J (2020) Auswirkungen von künstlicher Intelligenz auf Völkerrecht, insbesondere die Gewährleistung der Garantien des Art. 6 EMRK. Zeitschrift zum Innovations- und Technikrecht 3:145–150

Meuwese A (2020) Regulating algorithmic decision-making one case at the time: a note on the Dutch ‘SyRI’ judgment. Eur Rev Digital Adm Law 1(1–2):209–211

Milaj J, Mifsud Bonnici JP (2014) Unwitting subjects of surveillance and the presumption of innocence. Comput Law Secur Rev 30(4):419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2014.05.009

Mittelstadt BD et al (2016) The ethics of algorithms: mapping the debate. Big Data Soc 3(2):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716679679

Obispa G (2020) All Rise For The Robot Judge. Available via Profound. https://profoundprojects.com/insight/all-rise-for-the-robot-judge/

Ofterdinger H (2020) Strafzumessung durch Algorithmen? Zeitschrift für Internationale Strafrechtsdogmatik 9:404–410

Oswald M (2020) Technologies in the twilight zone: early lie detectors, machine learning and reformist legal realism. Int Rev Law Comput Technol 34(2):214–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2020.1733758

Oswald M, Grace J, Urwin S, Barnes GC (2018) Algorithmic risk assessment policing models: lessons from the Durham HART model and ‘experimental’ proportionality. Inform Commun Technol Law 27(2):223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600834.2018.1458455

Palmiotto F (2021) The black box on trial: the impact of algorithmic opacity on fair trial rights in criminal proceedings. In: Ebers M, Cantero Gamito M (eds) Algorithmic governance and governance of algorithms. Legal and ethical challenges. Springer, Cham, pp 49–70

Papadimitrakis G (2019) Big data and algorithmic risk studies. New challenges in the area of penology. [in Greek]. Poiniki Dikaiosyni 10:1045–1054

Quattrocolo S (2020) Artificial intelligence, computational modelling and criminal proceedings. A framework for a European legal discussion. Springer, Cham

Robinson D (2018) The challenges of prediction: lessons from criminal justice. J Law Policy Inf Soc 14(2):151–186. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/185249983.pdf

Ryan M et al (2019) Report on Ethical Tensions and Social Impacts. WP 1. D1.4 SHERPA. https://doi.org/10.21253/DMU.8397134

Sachoulidou A (2021) OK Google: is (s)he guilty? J Contemp Eur Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2021.1987863

Sachoulidou A (2023) Going beyond the “common suspects”: to be presumed innocent in the era of algorithms, big data and artificial intelligence. Artif Intell Law. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-023-09347-w

Singelnstein T (2018) Predictive Policing: Algorithmenbasierte Straftatprognosen zur vorausschauenden Kriminalintervention. Neue Zeitschrift für Strafrecht 37(1):1–9

Starr S (2014) Evidence-based sentencing and the scientific rationalization of discrimination. Stanford Law Rev 66(4):803–872

Strikwerda L (2021) Predictive policing: the risks associated with risk assessment. Police J Theor Pract Principl 94(3):422–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X20947749

Wexler R (2018) Life, liberty, and trade secrets: intellectual property in the criminal justice system. Stanford Law Rev 70:1343–1429

Wisser L (2019) Pandora’s algorithmic black box: the challenges of using algorithmic risk assessments in sentencing. Am Crim Law Rev 56:1811–1832

Završnik A (2019) Algorithmic justice: algorithms and big data in criminal justice settings. Eur J Criminol 18(5):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370819876762

Završnik A (2020) Criminal justice, artificial intelligence systems, and human rights. ERA Forum 20:567–583. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12027-020-00602-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sachoulidou, A. (2023). Algorithmic Criminal Justice: Is It Just a Science Fiction Plot Idea?. In: Kornilakis, A., Nouskalis, G., Pergantis, V., Tzimas, T. (eds) Artificial Intelligence and Normative Challenges. Law, Governance and Technology Series, vol 59. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41081-9_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41081-9_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-41080-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-41081-9

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)