Abstract

The provision of ‘buy-now-pay-later’ (BNPL) is changing relationships between consumers, credit providers, and retailers. This chapter develops a fine-grained understanding of the symbiotic dealings between these parties and discusses how their bonds may evolve given the intrinsic benefits and risks at play. In that respect, it is the nature of the functional and relational attributes that specific actors liberate through BNPL that frame their individual ‘wellbeing’ in this coopetitive ecosystem. The chapter also unmasks the range of potentially positive and negative outcomes amid the evolving associations. The individual outturns are inherently unequal, and there is considerable variance for actors—although the retailer consistently appears to be the weak, if not sometimes the weakest, partner. The research additionally highlights that BNPL providers’ efforts to create a consumption ecosystem that disrupts contemporary patterns have been fairly effective, as BNPL providers are consistently perceived as the strongest partner by UK consumers. The consumer appears to be the arbiter of which form of symbiosis is manifest and thus central to the ecosystem. It is clear that relationships will continue to shift, requiring flexible and active management between the network partners to ensure individual and collective survival and wellbeing—and ultimately determine the final nature of the BNPL ecosystem.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retail evolutions have irrevocably altered shoppers’ experiences—for instance through in-store self-service scanning, online shopping, and mobile one-click ordering. When considering these transformations, technology’s influence on how, where and when consumers shop is clear. The power of such technologies is manifest in the utilization of big data and in the systemic properties of the Internet and mobile networks. What is less obvious is the enabling role played by payment system changes in such retail shifts. In each example, shoppers’ ability to ‘tap and go’, authorize a transaction remotely, or deploy mobile payment are integral. However, the payment systems, and the organizations behind them, are perceived by consumers as ‘mere’ enabling factors and their role is, perhaps, taken for granted. Consumers often focus their attention and interactions on the retail offer. This is the prime relationship, one that retailers, understandably, seek to enhance through the provision of such technologically driven evolutions.

This familiar situation is now being subverted by the provision of ‘buy-now-pay-later’ (BNPL) services. These credit providers are attempting to change the relationship balance between consumers and retailers by altering consumer decision-making processes and consumption patterns. This is essentially a ‘fintech Footnote 1 makeover’, one that engages consumers, by transforming their retail experience, and reconfigures the value proposition generated between consumer, retailer, and credit provider.

This chapter develops a fine-grained understanding of the symbiotic relationships between these actors—BNPL-provider, retailer, and consumer—and discusses how these bonds are evolving, given the functional and relational benefits, and the risks, being generated. This is achieved by generating data using a story stem completion task with 533 UK BNPL-users (aged 18–35, as chief BNPL adopters) to unearth their changing perceptions of retailers and credit providers and to explore consumers’ emerging practices.

What Is BNPL?

Operated by companies such as Klarna, Clearpay, or PayPal, BNPL services are third-party short-term credit agreements presented to consumers at retailers’ checkouts, or accessed through BNPL provider apps. These services are apparent at various touchpoints and heavily advertised on social media. When offered by firms with established reputations, such services potentially increase consumer trust and reduce the perceived risk of online payment, especially when the retailer is unfamiliar (Cardoso & Martinez, 2019).

BNPL agreements defer payment of the full price (e.g. pay in 30 days), or split it into several instalments (e.g. three or four). Both formats are commonly available in most contexts, but consumer preference differs between countries. Irrespective of the format used, BNPL is short-term credit and unregulated in many countries—including the UK. Additionally, customer credit checks are not always necessary, or used by all providers. BNPL is usually interest and charge free if customers meet the agreed repayment schedules. In the UK, because of BNPL’s low consumer adoption barriers, user numbers and the total transaction value have grown significantly (Tijssen & Garner, 2021). This is also the only unsecured-lending product that accomplished ‘high-double-digit growth’ during the COVID-19 crisis.

BNPL use in the UK is particularly popular among Millennials (born 1980–1994) and Generation Z (born 1995–2009), who use it to buy essentials, for example, food, alongside luxuries (Mintel, 2022), often opting for the instalment option. Such consumers frequently have a limited credit history, making traditional credit methods that include cards and loans difficult to access, and find these payment methods unappealing. They prefer the rapid and frictionless processes and simple account management capacity that BNPL affords, making access to credit almost effortless. BNPL, however, is penetrating older age groups in the UK, and more generally, and is being employed across a wider spectrum of retail sectors, including high-end players, thus diversifying both the consumer and retailer base. Hence, BNPL is increasingly being used by customers who have high credit scores, although these tend not to use the same shorter-term instalment options as younger UK consumers, opting instead to defer payment.

BNPL and Changing Consumption Patterns

On the basis of the description above, ‘simply’ characterizing BNPL as short-term credit would be understandable. However, for many of the major players, such as Klarna, what has been created is a sophisticated integrated e-commerce environment that seeks to engage shoppers at each point of their customer journeys. The efficacy of this approach is manifest in the changing behaviour patterns and benefits that accrue to each actor—consumer, retailer and BNPL provider.

In general, consumers using BNPL make purchases more frequently, spend more per shop, and buy more often. Therefore, BNPL both facilitates affordability and develops habituation: It additionally bestows offers and discounts, further enhancing product attainability. These developments are driven by shopping that has ‘levelled-up’, a service that claims to enable a ‘shop smarter, not harder’ consumer experience. This may also help consumers limit the unhappiness they feel while spending and experiencing perceived financial constraints (Cardoso & Martinez, 2019). What is provided surrounds consumers with a seamless array of curated retail offers, savings, retailer loyalty card management facilities and, naturally, offers a means of administering payments for what is bought, including the ability to pause when finances are tight. Most BNPL providers thus do not simply offer consumers short-term credit, but a single-point gateway for shopping, saving, and managing their spending.

UK retailers have also acknowledged gains from BNPL: Unsurprisingly, therefore, three in four of firms include such services in their growth plans (Tijssen & Garner, 2021). In seeking to benefit from BNPL provider platforms, retailers—large and small—not only use these services, but also increasingly pursue primacy within BNPL platform listings.

BNPL providers derive income from both their retailer and consumer users. Retailer payment is gained for access to credit services, and for other benefits, for example, advertising and listing deployment on BNPL platforms. The BNPL provider also gains fees and interest from consumers if payments are overdue. This extends relationship timeframes and necessitates intensified management—potentially reinforcing the connection between BNPL provider and consumer.

Therefore, an interconnected web is created between the three actor groups, one that is altering consumption patterns by recasting the relationships at play. The position is further strengthened by decreased use of cash, increased mobile and digital payment adoption, and intensified online shopping. Understandably, BNPL providers are positioning themselves to capitalize on traditional relationship changes, and evolving the financial landscape into what Klarna (2022) calls an ‘ecosystem’.

This ecosystem is best described as ‘coopetitive’, as consumers, retailers, and BNPL providers simultaneously pursue individual and collective goals. Its creation has transformed the combination and balance of the functional and relational outcomes of each actor. Exploring this mix requires consideration of the pattern of possible outcomes—do all actors benefit, do they all lose, or do some win whilst others suffer, or remain unaffected—such considerations are currently absent (MacInnis et al., 2020).

Conceptual Concerns

Jacobides et al. (2018) suggest that ecosystems can be categorized into three streams: “a ‘business ecosystem’ stream, which centers on a firm and its environment; an ‘innovation ecosystem’ stream, focused on a particular innovation or new value proposition and the constellation of actors that support it; and a ‘platform ecosystem’ stream, which considers how actors organize around a platform” (pp. 2256–2257). BNPL could be viewed from within all three streams: Irrespective of which is used, each highlights the direct and indirect network effects that arise from the coordination, expectations, and compatibility of actor exchange (Rehncrona, 2022).

From the service perspective often applied to retailing, this interconnecting network ensures “individual survival/wellbeing, as a partial function of collective wellbeing” (Vargo & Lusch, 2017, p. 49; emphasis in original). Here, the concurrence of individual and collective wellbeing indicates coopetition, whereby mutually beneficial, and enduring, exchanges between actors are acknowledged, but so are issues of unequal power or information asymmetry (Zineldin, 2004). Hence, actors with greater power, or more information, can exploit these characteristics to further their self-interest within the network (Rehncrona, 2022; Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000). Therefore, actors simultaneously act in cooperation and competition. This duality might be categorized as symbiosis, whereby no participant would be able to obtain the potential network effects by existing on their own, instead similarly seeking to maintain the advantages of importance to them.

Many contemporary retail contexts provide evidence of such symbiosis, often supported through technological developments, be they social media platforms or various service aggregators or fintech applications—including BNPL (Rehncrona, 2022). Such technological developments are central to what have been termed ‘payment ecosystems’ (Hedman & Henningsson, 2015), which, for instance, address credit card operations, or mobile payment and BNPL. These innovations support actors pursuing their own advantage. For instance, consumers want convenient and affordable purchases, retailers want to maintain brand-consumer relationships by offering multiple payment methods, and BNPL providers want to increase their credit agreement numbers. However, in seeking these individual outcomes, there is a concomitant change in the nature of these relationships, particularly when BNPL providers have sought to mediate traditional consumer-retailer interactions by seamlessly interposing themselves. BNPL providers, hence, are seeking to become the single-entry point shopping platform, making BNPL more than a payment mechanism—rather the ‘consumption ecosystem’ of choice where consumer-retailer relationships are played out.

Hence, the triadic relationships are “unequal in depth” as “the ‘prime’ relationship” moves to that of the consumer and the BNPL provider (Worthington & Horne, 1996, pp. 191–192). Notionally, there is a shorter psychological distance between these two actors that enhances trust, while also increasing the information exchange and usage levels between them and developing into habits and routines. Whether or not this occurs is potentially a matter of ‘who introduces whom’ to the consumer. Where a consumer’s preferred retailer provides access to BNPL payment at the point-of-sale, the consumer may infer that BNPL is being endorsed and may hence adopt it (here, BNPL is operating as a ‘mere’ payment ecosystem). However, where a pre-existing BNPL user identifies a retailer advertised on the provider’s platform, the consumer may be more willing to purchase from this, hitherto, unfamiliar retailer (BNPL then acts as a consumption ecosystem). In both cases, there is a retailer-BNPL-provider relationship, and the consumer is the weakest partner as they are reliant on a structure they may not fully understand (Worthington & Horne, 1996) and due to the workings of the retailer-BNPL-provider relationship are likely to be opaque.

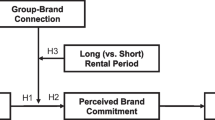

Figure 6.1 indicates how the pattern of relationships may vary between the three actors, depending on whether the consumer perceives BNPL to be a payment or a consumption ecosystem. This also suggests that complex interrelationships are generated that may result in varied forms of symbiosis. Five different possibilities have previously been identified on a broad continuum based on the overall wellbeing impact each partner incurs.

Box 6.1 A Taxonomy of Multipartite Symbiosis in Service Ecosystems

The associations of more than two entities (individuals or organizations) of different forms and with potentially distinct ideals where:

-

1.

Mutualism—reciprocal benefits are derived, which may be unequal in form and scope (win-win-win).

-

2.

Commensalism—an indirect diversion of energy for the profit of one or more entities is generated that does not damage the other parties (e.g. win-win-neutral).

-

3.

Parasitism—one or more entities adversely affect the other entities as an outcome of, at least in some (if not all), its practices and cycle of activities (e.g. lose-win-win).

-

4.

Amensalism—at least one entity is adversely affected by the practices and cycle of activities of another, whilst the other partner/s are unaffected (e.g. lose-neutral-neutral).

-

5.

Synnecrosis—reciprocal detriments are derived, which may be unequal in form and scope (lose-lose-lose).

(adapted from Worthington & Horne, 1998)

Given the preceding discussion, it seems plausible that the actor relationships in the BNPL ecosystem are unlikely to simply lead to the collective maximization of wellbeing (mutualism: win-win-win). Rather, the actors’ opportunistic behaviour and information, and power asymmetries, are expected to generate different relationship outcomes. Therefore, other forms of symbiosis will also occur, necessitating identification of the possible mix of win, neutral, lose outcomes for each actor.

To help provide a discriminating assessment of the BNPL ecosystem relationship outcomes for each actor (win, neutral, lose), the functional (e.g. fees) and relational attributes (i.e. social, special treatment and confidence/safety) that emerge need to be uncovered (Koritos et al., 2014). This requires consideration of what, potentially, each actor stands to win or lose, and what remains unaffected, and whether these outcomes rest on functional or relational attributes—Table 6.1 offers examples of what this might mean for the actors.

The following develops an understanding of the UK BNPL ecosystem by assessing the nature of the apparent functional and relational outcomes, hence identifying the emerging symbiotic relationship forms.

The Study

Data Generation

This chapter was created using a story stem completion task (projective technique) to explore the conscious and unconscious perceptions, motivations, and emotions that UK BNPL users (18–35 years) hold regarding BNPL services. Research panel members were presented with a visual (fictitious online store checkout page including four BNPL options) and ambiguous verbal stimulus. The latter asked participants to develop a short ‘story’ detailing what happens next and why, in response to the stem, “Sam spots a coat online that looks fantastic. It’s a little expensive, but worth the extra, even if Sam wasn’t really shopping for one today! When it comes to pay, Sam sees the following”.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used (Braun & Clarke, 2022), whereby the levels of symbiosis, as well as the functional and relational benefits, served as initial a priori codes. Extracts are introduced in the next section both to illustrate how consumers make sense of BNPL services and to present an analytic interpretation of the symbiotic interrelationships of the BNPL ecosystem.

Participants

In total, 533 BNPL users aged 18–35 contributed. Most identified as female (67.4%) and white (80.0%), and were in their upper twenties (M = 28.55, SD = 5.11). Nearly one in four participants (71.9%) were in full- or part-time employment. Approximately one-third used BNPL either often or almost always (26.0% and 6.3% respectively). Conversely, just over two-thirds used BNPL either rarely or sometimes (31.0% and 36.7% respectively).

Results

Mutualism (Win-Win-Win Outcomes)

While mutualistic relationships—by definition—hold benefits for all participants, consumer stories propose that BNPL providers are the prime partner in this form of symbiosis. This is not to suggest that consumers and retailers do not benefit from this interrelationship. Rather, it reveals that the real power evident in mutualism ultimately rests with the BNPL provider.

As exemplified in the following, consumers acknowledge the ‘smooth’ management of payments (consumers), accounts (BNPL providers), and checkouts (retailers) as the essential functional benefits of mutualism:

Definitely use Klarna and split the payment over three … months to make it more manageable. Klarna is simple and easy to use and reminds you when you will need to pay and will let you … [extend] it if needed. I personally use Klarna and wouldn’t use a different company because you then owe loads of companies instead of one. Making it harder to manage. (P525).

If I was Sam, I would use Klarna because they’re a great company and I would choose ‘the pay in three’ [payment option] as it’s easy and you don’t lose a lot of money all in one go. It’s easy to use … they just take a mobile number, send you a text message to verify, set up your account by adding all your personal details. (P424).

Checkout is easy on Klarna as long as [Sam] has an account which he does, and his purchase is complete in a matter of minutes. He set up a payment plan … for 3 months and splits the payment into 3 equal payments with no interest added onto this unless he doesn’t pay. (P290).

From the above, it appears consumer behaviour can best be described as opportunistic (e.g. payment by instalments), calculative (e.g. choice of BNPL providers), inertial (e.g. cognitive loyalty) and reliant (e.g. reminders). The latter also puts trust at the centre of the consumer’s relationship with the BNPL provider, which seems the strongest pairing in mutualism.

Interestingly, brands like Klarna use attributes like ‘trust’ and ‘empowerment’ to position themselves in consumers’ minds. But the stories presented here raise the question of whether BNPL tools and practices are truly designed to empower consumers towards financial ‘capability’ or ‘affordability’.

Commensalism (Mix of Win-Neutral Outcomes)

This form of symbiosis is characterized by a combination of win/neutral relationship outcomes. Many consumers experience confidence benefits (e.g. trust) from their relationship with particular BNPL providers (e.g. Klarna), for which they are prepared to pay a ‘price premium’ in the form of higher monthly instalments:

They are all quite appealing, though, it’s just–I do trust Klarna the most out of them all. Even though it offers the most expensive monthly instalments out of them all. (P157).

Financial decision-making, so it seems, involves relational and functional trade-offs, whereby the attributes of the former outweigh the latter. This, in turn, is indicative of the relational benefits BNPL providers might offer, with consumers appearing to forge psychological bonds with BNPL providers that are based on mediated experiences (e.g. advertising) alongside indirect (e.g. word-of-mouth) and direct (e.g. prior usage) lived experiences:

She [Sam] has seen a lot of advertising on social media and the TV about Klarna so knows that it is a reputable brand that a lot of people are using, and this reassures her as well. (P325).

Klarna seems like a popular option to pay as his [Sam’s] friends and family also use it, so he knows it’s trustworthy. (P181).

Sam clicks on the Klarna option to spread the payments into 3 monthly payments, because he’s used Klarna before and trusts their service. (P382).

In commensalism, the absence of any mention of retailers provides initial evidence that these have become mere transactional partners and thus they have the weakest links in this symbiotic form. This idea is summarized thus:

Even if Sam wasn’t looking for a coat, if he likes it, then he will surely buy it like in my case. If he has enough money on the card the[n] he would probably pay all at once by credit or debit card but if he plans to buy some other stuff, then he might use one of the other options that helps Sam to spread the cost. I would probably use Klarna, but all the others are a great help too. It’s great that now you have multiple choices on how to pay so you can do the one it’s best for your needs. (P400).

The above story highlights the neutral relationship outcome for retailers if consumers are presented with multiple payment options (e.g. card versus BNPL). This is because choice does not affect the ultimate outcome, namely sales. However, it is conceivable that payment options become consumption barriers for consumers who are overwhelmed by the amplification of choice.

Parasitism (Mix of Win-Lose Outcomes)

So, I would use one of these [BNPL] options as I wouldn’t want to miss out on a sale or discount code. I have a Clearpay account so use this quite often and it doesn’t feel like such a hard hit when paying for more expensive items. (P360).

The introductory quote reveals consumer appreciation of the special treatment (e.g. price cuts) received in parasitic relationships, disregarding potential losses for BNPL providers (e.g. lower transaction values) and retailers (e.g. slimmer margins). Rather, relational benefits become resources that cushion consumers from psychological and financial shock (pain), as the metaphor hard hit suggests. The frequent use of BNPL applications could be construed as an expression of trust in BNPL providers, who are believed to curate promotional offers with consumers’ interests in mind.

However, not all consumers seem to feel that way. Some have become mistrustful towards BNPL services, which, despite their increased proliferation, remain novel and thus unknown, unproven, and controversial—potentially damaging consumer trust (relational loss for BNPL providers). Few might develop an awareness of, a familiarity with, or a preference for specific BNPL providers who induce feelings of security and trust in an otherwise mistrusted environment. Lack of trust, mistrust, and distrust will result in BNPL providers’ inability to convert leads into new customers. These consumer views are summarized thus:

Sam sees lots of options he recognises like Klarna which he knows … But look there’s another option of paying even less for 6 weeks. But I don’t really know that company [Laybuy] and don’t want to risk it. Sam’s friend had difficulty with his credit after a dodgy encounter. No, Sam should use Klarna if he is going to spread the cost. (P19).

Consumer stories shed light on a different yet related issue. Some consumers have formed relationships with fintech service brands like PayPal and Google Pay, and expect to find them in the retail environment. The absence of these brands has detrimental outcomes, chiefly for retailers who forfeit sales transactions because they lack established relationships with consumers:

Why isn’t PayPal a payment option? Sam finds it off-putting if it’s not offered. They don’t want to sign up to Klarna or Clearpay. More personal information to share with more companies. More passwords to remember. More deadlines to miss. The coat sits idly in Sam’s online basket. Sam closes the tab – they weren’t even looking to buy a winter coat. (P489).

Implicit in the above quote is a trust transference from fintech brands to the retailer. It appears consumers become distrustful towards specific retailers in situations where transference is not possible:

I wouldn’t trust the site as much without PayPal or Google Pay. (P529).

Amensalism (Mix of Lose-Neutral Outcomes)

Some BNPL users expressed increased levels of anxiety (relational loss) during the pre- and post-purchase phases, as illustrated by this story:

Sam feels troubled. Should [he] buy or not? Yes, but the suggested payment method for Sam sounds attractive. But it is also difficult for Sam. It’s quite interesting that Sam doesn’t need to spend a lot of money at once but being able to pay monthly will help Sam reduce his anxiety right away. But buy now and pay later, Sam will have to worry about paying for the following months. (P162).

Pre-purchase cognitive dissonance (‘trouble’) arises from the evaluation of the available options (e.g. buy or not). BNPL is believed to reduce… anxiety in the present (right away) but raises repayment concerns (‘worries’) in the future (following months). It is conceivable that the projection of negative affect into the future (post-purchase phase) could inhibit BNPL use because some consumers might overestimate its future effect (impact bias).

Conversely, other consumers seem to embrace BNPL services and develop promiscuous consumption behaviours:

Sam chooses to use a buy now pay later service. Sam makes all his payments on time and gets more credit for the service. He then continues to use several different buy-now-pay-later services. Eventually, Sam uses buy-now-pay-layer services for nearly every single one of his purchases. His purchases then continued to be buy-now-pay-later again and again. Sam then goes to another shop and uses the buy now pay later services. Then he finds a different website and does it again. (P42).

Objectively, it is irrelevant to BNPL providers where consumers shop if using their services (neutral outcome). Equally, the choice of BNPL provider does not affect relationship outcomes for retailers (e.g. sales) and is thus neutral:

Clearpay would be the best choice to spread the cost further and not add any interest it is one of my favourites to use and would save having to spend a lot of money in one go. If this was not an option, then I would use Zip that offers interest-free payments over time and would not have to break into money I wasn’t planning to spend. If they were not available, then Klarna would be the next best choice. (P250).

As demonstrated, retailers facilitate the choice of payment form (BNPL) by creating a space where BNPL users can select BNPL providers in the consumer’s order of preference, preventing shoppers from dropping out of the sales funnel. Analogous to other forms of symbiosis, relationships might thus be strongest between consumers and BNPL providers, making retailers the weaker partner in the triad.

Synnecrosis (Lose-Lose-Lose Outcomes)

In synnecrosis, all actors experience detrimental relationship outcomes. Interestingly, however, the data indicates that losses are predominantly functional (e.g. consumer debt and missed transactions). What is more, stories emphasize consumers’ psychological and financial vulnerability to BNPL services in general, and retailers’ marketing practices more specifically, as illustrated by the notions of ‘seduction’ and ‘persuasion’.

This puts consumers in the weakest position of the triadic relationship, evoking feelings of stress (e.g. cognitive dissonance), impotence (e.g. loss of control), confusion (e.g. surprise), suspicion (e.g. manipulation), and ultimately mistrust directed at BNPL and distrust directed at retailers. Consumer responses are summarized thus:

Sam uses payment splitting options like these often, and at the time they seem like a tempting idea … but Sam is on a slippery slope to getting into financial difficulties. This, plus the iPad they got last month, their phone bills, and not to mention the splurge on ASOS a couple of months ago. It’s all getting out of hand, but Sam can’t see that, they rationalise it in their mind and buy the coat. (P401).

When presented with payment options Sam is surprised to see 4 different options for payments via instalments and wonders whether any of them are actually distinctly different from each other. After all, he will still be paying £80 for the coat. (P492).

Sam sees the options for purchasing the coat on credit. He thinks about how it would be really easy and convenient, and he could have the coat now instead of later. He clicks off the website because he understands the marketing techniques that can convince him to spend money he doesn’t have on items he doesn’t really need and no sane person would actually spend eighty quid on a single coat. (P340).

As revealed in the last story, some might feel it is the consumers who play the decisive role in synnecrosis as it is their own ‘fault’ if they fall for the ‘scam’ and end up on the slippery slope towards debt.

Discussion

Prolific BNPL market growth in the UK, and beyond, has seen consumers provided with a new form of short-term deferred credit. More importantly, BNPL offers a potentially new consumption ecosystem, one that has the capacity to become the e-commerce portal of choice—making the prime relationship between consumer and BNPL provider. This goal is specified in Klarna’s (2022, p. 5) corporate communications, suggesting the company wants to create an ecosystem that provides consumers with the control they need to save time and money, ultimately helping them manage their finances and experience less stress. BNPL providers in the UK also promote other consumption pattern changes—for example, encouraging more spending per transaction, buying more often, and using BNPL to access an increasingly wide range of products (Mintel, 2022). However, there is little research that considers whether or not these objectives have been realized, thus helping to distinguish whether consumers view BNPL as a ‘payment’ (Hedman & Henningsson, 2015) or as a ‘consumption’ ecosystem.

To respond, attention needs to be paid to all network participants and the nature of their symbiotic relationships, rather than limiting deliberation to partner dyads. However, there is limited understanding to date of how the rise of BNPL is altering the balance of the relationship outcomes for the consumer, retailer, and BNPL provider. By drawing on ideas surrounding ecosystems (Jacobides et al., 2018; Rehncrona, 2022; Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000; Vargo & Lusch, 2017), on early insights into symbiosis in financial services (Worthington & Horne, 1996), and on the functional and relational attributes that emerge (Koritos et al., 2014), this chapter has sought to establish a fine-grained understanding of the permutations regarding who is unaffected, who stands to win or lose, and the nature of the functional or relational attributes of each case.

The findings suggest that in both mutualism (win-win-win) and synnecrosis (lose-lose-lose), the focal gains and costs highlighted for all the actors are functional. As these are the most extreme forms of symbiosis, this is perhaps because the direct and indirect network effects relate to the obvious and practical attributes distributed amongst the partners. This view would be in line with earlier work done in services suggesting that functional benefits predominate. However, the liberation of these functional outputs can also generate (dis)trust as a relational attribute that flows across the ecosystem (Rehncrona, 2022; Rousseau et al., 1998), (dissolving) cementing bonds and the interdependencies between partners. This (dis)trust equally defines the participants’ responses—in mutualism, scaffolding consumers’ resourceful and considered behaviours and, in synnecrosis, provoking a negative psychological state and uncertainty. Irrespective of the turn taken, it appears UK consumer responses determine the nature of the concomitant outcomes for both the retailer and BNPL provider. However, that does not make the consumer the strongest partner, as the data from both mutualism and synnecrosis illustrate, participants in both acknowledge that they may struggle, or fail, to meet payments even where win-win-win situations are identified.

When the other forms of symbiosis are considered, the primacy of functional qualities is drawn into question—and relational attributes dominate participants’ accounts, which is in line with the findings of Koritos et al. (2014). Here, social attributes abound (e.g. (dis)trust), with special treatment (e.g. discounts) and confidence and safety (e.g. anxiety, surety) also being evident, particularly in relation to consumer outcomes. These aspects are formed over a substrate of functional attributes that emanate from the operation of the ecosystem.

Within all participant narratives, irrespective of which form of symbiosis they provide evidence of, it is clear that the nature of the relationships is not equal, and that the overall wellbeing of each entity does not always improve (Worthington & Horne, 1996). It is, therefore, instructive to consider which pairing in the triad demonstrates the shortest psychological distance, and who is the dominant actor (strongest partner) in the UK context.

In all cases, the relationship between the consumer and the BNPL provider appears closest—in the participant excerpts, the retailer is often excluded or afforded limited consideration. Retailers are demoted to a necessary partner, but are rarely accorded primacy—hence, they are consistently perceived as the weak partner. It is the BNPL provider that is strongest, with consistent reference being made to the development of trust in this actor and the creation of psychological bonds and identification with specific BNPL providers. Participants particularly viewed Klarna as a trusted partner, highlighting that its platform has made purchasing ‘smoother’ for its customers. Here, the notion of ‘customer ownership’ is telling, underscoring that the retailer-customer relationship has effectively been disrupted and suggesting the retailer has even become the weakest partner in many forms of symbiosis.

When synnecrosis is examined specifically, another view of the consumer might also be proffered, one in which they are the weakest partner, bearing the greatest number of both functional and relational losses. This again emphasizes the relative imbalance of power and information asymmetry (Zineldin, 2004) within the ecosystem, as both retailers and BNPL providers have significantly more resources, enabling the effective management of their self-interest at the consumer’s expense. However, it does not preclude the existence of consumers with considerable knowledge and financial skill who use BNPL to further their consumption practices in a manner that elevates their self-interest over that of the other partners (Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000).

Given the diversity of the relationship depths and configurations, alongside the reliance on the collective alignment of the network (Vargo & Lusch, 2017), the UK BNPL ecosystem is most certainly coopetitive (Zineldin, 2004) due to the concurrence of individual and collective wellbeing. This creates both potential opportunities and challenges for the various symbiotic forms evident (MacInnis et al., 2020). The diversity of the participant accounts across the forms of symbiosis suggests that, for some consumers, BNPL is moving towards becoming a consumption, rather than a payment, ecosystem—where the consumer-BNPL-provider relationship is prime. However, other consumers see it as a payment ecosystem, often foregrounding the management of payments as their principal BNPL concern, rather than dwelling on the provision of more general consumption outcomes. Hence, the nature of the BNPL ecosystem is still emerging—and it will be the nature of the forms of symbiosis, as well as the concomitant mix of functional and relational attributes derived for all the actors, that will determine what gains dominance.

Conclusion

Given the understandings this chapter begins to bring to the surface, the functional and relational attributes that specific actors liberate using BNPL frame the scope and nature of their individual ‘wellbeing’ in this coopetitive ecosystem. The individual outturns are inherently unequal, and there is considerable variance for the actors in each form of symbiosis—although the retailer consistently appears to be the weak, if not sometimes the weakest, partner. What is also telling, if not unexpected, is that the consumer appears to be the arbiter of which form of symbiosis manifests itself.

To capitalize on the current situation, BNPL providers are positioning themselves as more than just a payment ecosystem, generating environments that seek to transform the consumer experience and reshape the value proposition into one where retailers are a necessary, but no longer primary, constituent. This movement is supported in the UK by many consumers pursuing short-term credit, to both access goods and to (better) manage their finances, during uncertain times. The changing payment landscape offers consumers additional opportunities to spend without ‘feeling’ they have made a dent in their income—something that may be sought after in many countries given the current financial landscape.

In that manner, BNPL offers both an incentive to spend, fostering potentially unsustainable patterns of consumption, and a safety net regarding access to goods through deferred payment or instalments. This is reshaping customer expectations in the UK, and potentially more internationally: Rather than thinking about what is wanted and then managing how to afford it, BNPL providers first offer their consumers the means of access and then present a menu of available consumption choices. The more consumers recognize and value this pattern, the more the retailer will be demoted to the weak, or weakest, partner in what will become a BNPL consumption ecosystem.

However, in offering a nuanced insight into the complexities at play, this research also suggests that reducing the outcomes to a uniform set of benefits or losses for each partner is a considerable oversimplification, both in terms of what the UK data presents and potentially more generally. As such, current understandings need to be elaborated to encompass the multipartite nature of BNPL and the apparent varied forms of symbiosis. This will help determine whether BNPL is viewed as a payment or a consumption ecosystem, dependent on consumers’ relationships with what is being offered in different locations.

For UK consumers, the findings provide evidence that functional benefits, and just as importantly losses, underscore symbiotic outcomes: However, it is the relational attributes that seem to define the nature of the prevailing consequences (win, neutral or lose). In this respect, BNPL providers in the UK, and more generally, are working hard to build up consumer ‘wins’ such as loyalty and attachment through aggressive advertising, targeted discounts and savings, widening the range of retailers and brands with whom they have direct connections to amplify product choice. These approaches, alongside the potential to individually tailor BNPL offers (e.g. loyal customers receiving longer credit terms or accessing specific discounted packages containing offers from multiple retailers), or BNPL’s participation in open banking to influence consumers’ wider financial activities, suggests a move towards an increasingly integrated and engaging experience. An experience that not only influences consumers’ shopping, but potentially also their entire approach to financial management and possibilities, underpinning a full-fledged consumption ecosystem. However, for a significant number of UK consumers, the relational outturns work to generate (dis)trust chiefly in the BNPL provider or mistrust in BNPL more fundamentally, and thus these consumers will remain outside, or on the periphery, of BNPL: For them it will remain at best a payment ecosystem.

For the BNPL provider, the research highlights that efforts to create a consumption ecosystem that disrupts contemporary patterns and relations have been somewhat effective since BNPL providers are consistently perceived as the strongest partner by UK consumers. The retailer becomes relegated, with this presenting considerable provocation and beginning to call into question the understandings of retailer-consumer relationships previously wrought on simpler dyadic assumptions. Hence, more work is needed to delve into the nature of the individual outturns of the BNPL ecosystem in all its varied forms, both in the UK and in other contexts.

It is equally clear that the individual actor outcomes work together to influence the collective relationships and wellbeing, which then define the general BNPL ecosystem. This network exhibits systemic attributes of collective wellbeing, perhaps the most evident being the formation of the trust, distrust, and mistrust embedded within yet wider institutional mechanisms and drivers, for example, dominant views of consumption or prevailing economic conditions. Here, again, there has been no concerted investigation and much needs to be done, whether this be considering the interplay denoting network purpose, the varied nature of collective wellbeing that might be present for different forms of symbiosis, and the impact of the varied environmental conditions of different locations, which cannot be separated from the holistic quasi-organism that is BNPL. There is likely to be considerable development. Firstly, as BNPL providers evolve and perhaps become embedded in open banking systems in some countries, they extend their operations to manage retailers’ digital and physical checkouts. Secondly, many consumers are struggling in the current global economic conditions and are, therefore, seeking smarter finance-centric solutions. Thirdly, retailers are now fighting to maintain their consumer relationships and are working to navigate their evolving role in consumption.

Hence, the findings raise several managerial implications: Firstly, for BNPL providers, they highlight that, where consumers derive functional and relational losses, synnecrosis is likely. Therefore, all partners suffer and BNPL is likely to be ‘just’ a payment ecosystem. This suggests that consumers need to be assisted in avoiding debt and its resulting negative psychological outcomes to maintain win (or neutral) outcomes. This management of customer outcomes into a more neutral or positive framing is also beneficial for the other ecosystem actors, and hence is not lacking in self-interest for BNPL providers and retailers. This might be achieved through consumer education in relation to fiscal management, additional support in terms of BNPL account management, or even in terms of curtailing spending or being more actively engaged in open banking. Such efforts would certainly align with Klarna’s espoused mission in suggesting it wants to make the task of payment as safe, simple, and primarily, as ‘smooth’ as possible. However, such actions also run counter to the patterns in the information that this BNPL provider offers to entice retailers in a number of locations into using the platform, that is, greater spending by consumers, more frequently. Hence, issues concerning the management of systemic versus individual actor wellbeing are brought to the fore and need careful balancing to realize a more full-fledged consumption ecosystem. There is also the spectre of the entry of another network partner, both in the UK and increasingly also in other contexts—that is, the regulator—who may help define the managerial responses available to BNPL providers.

Secondly, given the results, retailers appear to be facing considerable challenges. How are they to maintain their relevance and position, as well as avoid, as seems to be happening in the UK, being relegated in terms of their consumer-brand relationship. Evidence suggests retailers can disrupt the triadic relationship. Vendors can reduce the psychological distance between their brand and consumers by actively managing payment options and marketing solutions themselves. Retailers can even eschew the potential to have BNPL providers manage their checkouts and consider how to create competition between BNPL providers. This can help to build a customer repertoire of financing possibilities and focus attention on those the retailer deems preferential for the consumer. In essence, consigning BNPL providers to a more traditional financial services relationship role, that of payment ecosystem. Equally, if managed differently, the balance between the two organizational partners might become equalized in the UK and beyond. This stability might be achieved, for instance, through the creation of stronger retailer and BNPL provider bonds to generate targeted consumer discounts, or preferential financing options borne by the BNPL provider but only available through a specific vendor. Retailers can similarly galvanize their marketing efforts to respond to the evolution of the BNPL marketplace, reconfiguring and placing renewed effort in the establishment of consumer-brand relationships. This might be done by individual retailers or by leveraging network benefits jointly with other retailers. Here, it needs to be remembered that this coopetitive ecosystem contains many consumers, growing numbers of BNPL providers and numerous retailers. Hence, the organizational players, in addition to establishing relations between actors, are also free to foster them within an actor type. This will bring both solutions and new challenges.

Finally, BNPL and retail managers are advised to acknowledge the broader socio-economic context. For instance, it is conceivable that the proliferation of BNPL services (market growth) is stimulated by economic downturns (bust) whereby younger and financially vulnerable consumers especially depend on alternative payment options like BNPL to stretch their budgets. Analogously, consumers might be less prone to manage their finances during phases of economic growth (boom), moving retail brands back to the centre of their consumption. It follows as a corollary that relationships will continue to shift, requiring flexible and active management, together with all network partners, to ensure individual and collective survival and wellbeing, ultimately determining whether BNPL, in each context it operates in, is more a payment or a consumption ecosystem.

Notes

- 1.

Financial technology.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Cardoso, S., & Martinez, L. F. (2019). Online payments strategy: How third-party internet seals of approval and payment provider reputation influence the millennials’ online transactions. Electronic Commerce Research, 19(1), 189–209.

Hedman, J., & Henningsson, S. (2015). The new normal: Market cooperation in the mobile payments ecosystem. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14(5), 305–318.

Jacobides, M. G., Cennamo, C., & Gawer, A. (2018). Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strategic Management Journal, 39(8), 2255–2276.

Klarna. (2022). Klarna Bank AB Annual report 2021 (EN). Retrieved July, 16, 2022 from https://www.klarna.com/assets/sites/15/2022/03/28054307/Klarna-Bank-AB-Annual-report-2021-EN.pdf

Koritos, C., Koronios, K., & Stathakopoulos, V. (2014). Functional vs relational benefits: What matters most in affinity marketing? The Journal of Services Marketing, 28(4), 265–275.

MacInnis, D. J., Morwitz, V. G., Botti, S., Hoffman, D. L., Kozinets, R. V., Lehmann, D. R., et al. (2020). Creating boundary-breaking, marketing-relevant consumer research. Journal of Marketing, 84(2), 1–23.

Mintel. (2022). Fashion accessories – UK – 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 from https://reports.mintel.com/display/1123677/

Rehncrona, C. (2022). Payment systems as a driver for platform growth in e-commerce: Network effects and business models. In M. Ertz (Ed.), Handbook of research on the platform economy and the evolution of e-commerce (pp. 299–323). IGI Global.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404.

Singh, J., & Sirdeshmukh, D. (2000). Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgments. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 150–167.

Tijssen, J., & Garner, R. (2021). Buy now, pay later in the UK: Consumers’ delight, regulators’ challenge. Bain & Company.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2017). Service-dominant logic 2025. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(1), 46–67.

Worthington, S., & Horne, S. (1996). Relationship marketing: The case of the university alumni affinity credit card. Journal of Marketing Management, 12(1–3), 189–199.

Worthington, S., & Horne, S. (1998). A new relationship marketing model and its application in the affinity credit card market. The International Journal of Bank Marketing, 16(1), 39–44.

Zineldin, M. (2004). Co-opetition: The organisation of the future. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 22(7), 780–790.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Relja, R., Zhao, A.L., Ward, P. (2024). Friend or Foe? How Buy-Now-Pay-Later Is Seeking to Change Traditional Consumer-Retailer Relationships in the UK. In: Bäckström, K., Egan-Wyer, C., Samsioe, E. (eds) The Future of Consumption. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33246-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33246-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-33245-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-33246-3

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)