Abstract

Exercising agency is an inherent component of peer assessment. However, the research on agency in peer assessment is scarce. This case study explored how seventh grade science students exercised agency during formative peer assessment. The data comprises audio recordings of students’ classroom discussions, written peer feedback, written work, student interviews, and the researcher’s field notes. With thematic analysis, we identified nine forms of agency as associated with three positions: group member, assessor, and assessee. An examination of student interactions revealed that peer assessment challenges students unequally. While some students exercised certain forms of agency without difficulty—judging their peers’ work, for example—others needed help. One reason participants fell short in advancing their and one another’s learning during peer assessment was their difficulty exercising agency. Hence, equipping students with knowledge, skills, and a sense of responsibility is not enough; rather, their agency needs to be supported to enable the productive implementation of peer assessment.

We have no conflicts of interest or no funding.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Assessment and feedback have traditionally been the provinces of teachers, but that approach is changing (Boud, 2014). In higher education, researchers have emphasized the need for students to actively participate in feedback processes (Carless & Boud, 2018; Dawson et al., 2019; Winstone et al., 2017). In secondary education, same trend can be seen in the schools’ and researchers’ interest in self-assessment and peer assessment. However, the research on peer assessment has significant gaps. Studies have been largely concerned with its cognitive side (Panadero et al., 2018) and have paid little attention to sociocultural perspectives (Panadero, 2016; van Gennip et al., 2009). This is a serious gap, given that the social dimension is an elementary part of peer assessment (Panadero, 2016).

This study considers the social dimension of peer assessment by employing the notion of students’ agency. Agency can be defined as a “socioculturally mediated capacity to act” (Ahearn, 2001), which signifies that agency is considered as an interplay between individuals and their environment. Peer assessment promotes student agency by giving students the formal roles of assessor and assessee. However, assigning formal roles is only the beginning, since agency is coproduced in classroom environments as interplays between the teacher and students and among students themselves (Charteris & Thomas, 2016). According to research, students will not necessarily embrace their active roles. They may question their ability as assessors (Mok, 2011) or feel uncomfortable criticizing their peers’ work, even though criticism is officially sanctioned (Foley, 2013; Harris & Brown, 2013). Additionally, students may resist their peers’ feedback (Foley, 2013; Panadero, 2016), worry about the effects of peer assessment on their social relationships (Harris & Brown, 2013), and let relationships influence the feedback they provide (Panadero & Jonsson, 2013). The findings reveal that social and cultural features play roles in peer assessment and that students’ agency does not always take constructive forms but can be practiced in harmful ways (Harris et al., 2018).

In general, the literature on assessment and agency is in its infancy (Nieminen & Tuohilampi, 2020), particularly that focused on peer assessment and agency. Even though student agency is considered a necessary ingredient in formative assessment (Harris et al., 2018) and a rationale for using it includes the fact that it increases students’ active role in assessment and learning (Boud, 2014; Braund & DeLuca, 2018; Panadero, 2016; Topping, 2009), little is known about the forms of agency that students exercise during peer assessment. In the present study, we advance the understanding of the topic by exploring lower-secondary students’ forms of agency when formative peer assessment was repeatedly used in their science studies.

1.1 Formative Peer Assessment

Peer assessment has many variations. It can be used for summative or formative purposes, and it can be operationalized face to face or at a distance between individuals, pairs, or groups (Topping, 2013). This study only considered the formative purpose, which is the advancement of students’ learning; it did not focus on measurements of student learning, which is the purpose of the summative approach. According to Black and Wiliam (2009), the same assessment instruments (e.g., tests, projects, self-assessment, and peer assessment) can be used formatively and summatively, meaning the function of the assessment defines its type, not the assessment itself. Peer assessment is formative when its goal is helping students understand intentions and the criteria for success as well as activating them as instructional resources for one another (Black & William, 2009). Teachers are responsible for creating a learning environment, articulating that the aim of peer assessment is to advance learning, and delivering instructions that support that intention (Black & William, 2009). Topping (2013) defined peer assessment as “an arrangement for classmates to consider the level, value, or worth of the products or outcomes of learning of their equal-status peers” (p. 395), and argued that both receiving and providing feedback are beneficial. Hence, the strategy of activating students as instructional resources for each other (Black & Wiliam, 2009) entails two separate goals: guiding them to be instructional resources for others (assessor’s objective) and guiding them to use others as instructional resources (assessee’s objective).

Researchers have reached the consensus that peer assessment requires training (Sluijsmans, 2002; Topping, 2009; van Zundert et al., 2010). Peer assessment comprises several phases: developing original work, providing feedback, receiving feedback, and revising one’s own work (). Acting as an assessor or assessee requires diverse skills that vary depending on the form of peer assessment. Assessors need to understand their responsible position as providers of feedback (Panadero, 2016), understand the assessment criteria, judge the performance of a peer, and formulate constructive feedback (Sluijsmans, 2002). Assessees need to be able to judge feedback, manage affect, and act on feedback (Carless & Boud, 2018). These skills are needed in peer assessment, and they can be further developed by practicing it (Ketonen et al., 2020a, 2020b).

1.2 Agency in Peer Assessment

Depending on the research tradition, the concept of agency has different definitions and emphases (Eteläpelto et al., 2013). In this section, we discuss three aspects of agency for which researchers’ views diverge, and we clarify our stance toward them. The first concerns the ontological dimension of agency—more precisely, the extent to which agency is considered an individual versus a social attribute. At one end of the spectrum, agency is construed as an individual’s autonomous, rational actions; at the other, it is construed as shaped by structural factors, even to the point that the existence of agency is questioned (Eteläpelto et al., 2013). We take a middle ground in this research, following Billett’s (2006) theorization of the “relational interdependence” between individual and social agency. Billett (2006) suggests that individuals practice agency by choosing which problems and social suggestions they engage in and by regulating their level of engagement when participating in these undertakings. Hence, individual agency has a social origin, but it is not socially determined. When considering schools, students’ levels of agency may vary even within a single classroom because there are various microenvironments for participation (e.g., the whole class, a small group, or pairs) and social roles (e.g., colleague, peer assessor, or friend) offering different kinds of social suggestions and problems to engage in.

Temporality is another aspect in which the views of agency diverge. Some approaches do not consider the temporal element of agency, whereas others do (Eteläpelto et al., 2013). In this study, as presented by Emirbayer and Mische (1998), we construe students’ agency as a composite of past, present, and future, which are all relevant when practicing peer assessment. First, students’ agency in the classroom builds on experience. Even the first time they engage in peer assessment, students bring their experiences of learning, being assessed, and correcting and advising others. Their former ways of participating have developed patterns of agency that create expectations for their participation (Gresalfi et al., 2009). Second, agency is derived from imagined outcomes of action. Students visualize the consequences of complimenting and criticizing their peers, and apart from how those choices’ influence learning, they weigh their influence on their relationships with their peers and teacher. Third, agency is enacted in the present, which is not necessarily a straightforward process. For example, the act of providing feedback during formative peer assessment might demand considerations of the assessed work, the assessment criteria, one’s own capacity as an assessor, the teacher’s expectations, and the social norms and relationships in the classroom.

The third aspect of agency that has different emphases in the literature is the requirement of transformation. Some researchers highlight the transformative nature of agency and define it as transcendence of established patterns (Kumpulainen et al., 2018; Matusov, 2011; for transformative agency see Sannino, 2015). Others suggest that exercising agency does not require bringing about a change (Biesta & Teddler, 2007); instead, adaptive behaviors, such as seeking help, self-regulating, and setting goals, are also forms of agency. From such a perspective, students never lack agency completely; rather, they can always exercise at least a minimal amount of agency via either compliance or resistance (Gresalfi et al., 2009). Furthermore, forms of agency cannot be categorized as good or bad. For example, resisting authorship (Matusov et al., 2016) is neither unambiguously right nor wrong but rather reflective of students’ interpretations of tasks, environments, and their positions within those environments. Students can use either compliance or resistance as a means to achieve their goals. For example, by working hard and utilizing feedback, students can pursue learning or good grades; conversely, by rejecting feedback and purposefully underperforming, they can protect the ego from criticism or manage an overwhelming workload (Harris et al., 2018). In this study, we take the stance that transformative behavior is not the only way of exercising agency; rather, agency can also be seen in adaptive behavior.

1.3 Study Objective

In this study, we explored students’ actions during formative peer assessment during science studies in a lower-secondary school. The objective was to advance understandings of students’ agency during peer assessment. The research questions are set out below.

-

1.

What forms of agency do students exercise during formative peer assessment?

-

2.

How do students exercise agency in different positions that peer assessment offers them with respect to other students?

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

This study was carried out in a standard classroom in a typical lower-secondary school in Finland; most of the students were born in Finland, and there was a roughly equal share of boys and girls. As to participants, we selected four seventh grade students (mean age: 13 years). The criteria for selection were that they had participated in all the types of peer assessments and a majority of the peer assessment training sessions during the study and did not seem to struggle with motivation or have particular challenges with learning. All four students’ attitudes toward science learning and peer assessment appeared positive. We made the choice to examine the role of agency when students were willing to participate in peer assessment. If a student struggled significantly with learning, the potential reasons for that disengagement or misbehavior were wide ranging and thus not only related to peer assessment. In this exploratory study, we sought to exclude such factors.

Two participants, Rachel and Maggie, worked in the same group of four students, while Lucas and Nathan in another group of four students. Students studied physics for half their fall semester and chemistry for half their spring semester (Fig. 17.1). These were their first physics and chemistry courses and were taught by a subject teacher. Students first received training in peer assessment and then performed assessment three different ways, twice in physics and four times in chemistry.

The training included class discussions and written tasks. Over six weeks, there were seven 10- to 45-min sessions, which are further described in Table 17.1 and in (Ketonen, 2021). The overarching message of the training sessions was that peer assessment was for learning. The assessors’ goal was to help classmates progress, and the assessees’ goals were to respect peers’ assistance and use feedback if possible.

The peer assessments had different organizational forms and objectives, which are further explained in Table 17.2 and further in (Ketonen, 2021).

2.2 Research Design and Data

Since the goal of the study was to explore what happens in a classroom during peer assessment, a naturalistic study setting and a qualitative case study design were chosen. The data consisted of audio recordings of students’ classroom discussions, written peer feedback, written work, student interviews, and the researcher’s field notes. The first author observed the participants and made field notes during most of the 36 lessons of 1.5 h each. At the beginning of each lesson, she placed audio recorders on the tables of each student pair. The recorders captured students’ conversations during the lessons. Students’ written work included original and revised versions of their peer-assessed work and written peer feedback. All students were individually interviewed after PA2 and PA3. In semi-structured interviews that took from 6 to 11 min, their original work, revised work, and received feedback were used as bases for the conversations. An average interview followed the chronology of the peer assessment: it started with questions about the student’s perception of their original work, turned to their consideration of the assessed work and the feedback they provided to others, continued to the feedback they had received, and the changes they were considering as a result of the peer assessment. If a student led the conversation to other topics, these were discussed, and this sometimes changed the order of the interview elements.

2.3 Analysis

The interviews and class discussions during peer assessments were transcribed, while written feedback and work were scanned, and each student’s data were compiled in chronological order. Peer feedback sheets described what kind of feedback students had provided and received, and their preliminary and final work provided information on how they went about their revisions. Students’ conversations in their groups and working pairs provided additional information related to providing and using feedback. Students’ written work, classroom discussions, and written feedback were used as primary data sources, and interviews and observations were used to complement and explain the findings. The first researcher, who had taught at the school for some time, was responsible for the coding. She read the files carefully multiple times. Then she analyzed the data using a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). She marked data extracts containing information about students’ agency during peer assessment and labelled them with descriptive codes. Gresalfi et al.’s (2009) description of agency was used to identify extracts relevant to our study purpose: “An individual’s agency refers to the way in which he or she acts, or refrains from acting, and the way in which her or his action contributes to the joint action of the group in which he or she is participating” (p. 53). A unit of analysis was one student’s data in one peer assessment in one role, for example, all of Student 1’s data while they were an assessor during PA1. Since individual students’ ways of participating in certain peer assessments were intertwined and partly explained each other, the researcher first coded all students’ data from PA1 and proceeded chronologically through the remaining assessments.

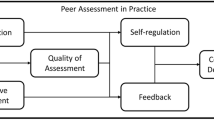

After coding the whole data set, the researcher retrieved and examined data extracts and codes, developed preliminary categories of student forms of agency, and wrote descriptions for each. When developing the categories, she compared the codes to data extracts in each one to consider their internal consistency, and then she compared the categories with each other to examine their distinctiveness and coherence, which led to changes to the codes. After, she recoded the data set with new codes. To test, discuss, and develop the coding and to support the entire process, we used peer debriefing (Onwuegsbuzie & Leech, 2007). The second and third researchers, who were not involved in the field work, asked critical questions and explained their views of the first researcher’s codes and categories. The iterative process of coding, comparing codes and categories, and revising them continued until it did not produce any changes. Then the researcher named the categories and wrote the final category descriptions. The categories’ relationships were elaborated with a thematic map (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We noticed that the forms of agency were related to the positions of assessor, assessee, and group member (Fig. 17.2). Given that agency is a relational and context-dependent construct, this finding was significant. In the last phase, we examined individual students’ ways of exercising agency in each of these three positions, thus answering research question 2.

3 Results

In this study, we explored the forms of agency that students exercised during formative peer assessment in different positions with respect to other students. We found 12 forms of agency that related to three positions. These are presented in Table 17.3. As group members, students were on an equal footing with their peers; as assessors, they were in an advisory position; and as assessees, they were in receiving position. In some cases, students worked in several positions concurrently, such as when they acted as assessors in a group. The finding revealed that students conducting peer assessment act in various positions in relation to each other and the way their agency presents itself depends on that position.

In the following three sections, we introduce and compare the forms of agency within the position in which each form was exercised.

3.1 Exercising Agency as a Group Member

As group members, students exercised agency by initiating or echoing ideas. In their respective groups, Nathan and Maggie echoed others’ ideas, while Lucas and Rachel were active in introducing original ideas, whether providing or receiving peer feedback (Fig. 17.2). Lucas and Rachel expressed their ideas without difficulty, whereas Nathan and Maggie hesitated to make suggestions even when they built on others’ ideas.

The following example of initiating is from PA1, in which Rachel and Maggie, and their two other groupmates, Mia and Tara, assessed another group’s work. The assessed task was a plan for a mobile rover that could be built with available resources (see Ketonen, 2021 for more information). Below, the exchange begins with the group’s first comment on the other group’s plan.Footnote 1

1 | Tara: | (Quoting other group’s plan) “Rubber band, catapult … |

2 | tail end.” | |

3 | Rachel: | It does not say what [materials] they need there |

. (Discussion unrelated to peer assessment and physics) | ||

14 | Tara: | Once nothing else is needed, |

15 | they can write what they need | |

16 | Rachel: | Yeah, they can write there what they need, |

17 | and then they can draw it, like, from below— | |

18 | the bottom | |

19 | Like, from the bottom angle | |

20 | Tara: | From the bottom |

21 | Maggie: | And from above, |

22 | not just from the side |

Right after seeing the other group’s plan, Rachel argued that they had not listed what material they would use to build their rover (2), and later, she proposed the need to draw the model from different angles (17, 19). At that point, she put forward two ideas that were echoed by other group members, thus practicing the initiating form of agency. Tara repeated Rachel’s first (14) and second (20) ideas and Maggie elaborated on Rachel’s second idea (21–22).

The difficulty of initiating new ideas became apparent when students assessed the next group’s work. Rachel—the former initiator—was concentrating on another issue, and the other three group members were left with the job of providing feedback. First, they took considerable time comparing Maggie’s handwriting to that of the assessees. When they turned to assessing, the conversation below took place.

37 | Maggie: | There could have been… (silence) |

38 | Tara: | If … |

39 | nothing. (Silence) | |

40 | Maggie: | This could have been better planned |

41 | Like, they could write what everyone brings or something | |

42 | Mia: | But it’s there |

43 | Maggie: | Right. (Silence) |

44 | Maggie: | This could have been drawn from several |

45 | different angles | |

46 | Mia: | Yeah, right |

47 | Maggie: | How should I formulate it? |

48 | Mia: | Could you have done it from several angles? |

The students tried to provide feedback, but they either did not come up with any ideas or did not feel comfortable expressing them (37–39). After a while, Maggie raised Rachel’s previous idea of listing the required material (41). After Mia pointed out that the material were already listed (42), Maggie took a moment to rethink and suggested Rachel’s other previous idea about drawing the rover from different angles (44, 45). This was accepted (46) and written on a Post-it Note. This excerpt demonstrates that even when assessors are willing to provide feedback, new ideas may not be put forward, which constitutes a lack of initiation. Having an initiator in a group supported others in assessing their peers.

3.2 Exercising Agency as an Assessor

As the previous section showed that initiating ideas was challenging to some students, one may wonder how they exercised agency, when they were supposed to work as individual assessors during PA2. Students’ diverse ways of exercising agency are presented in Fig. 17.3. The assessed task was a lab report about determining the speed of the previously planned and built rover. The inquiry was conducted in groups, but the reports were individually written. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Rachel and Lucas—who, much like Rachel, had initiated ideas in his group—assessed their peers’ work without difficulty. They concentrated on assessing for a moderate amount of time and provided both confirming and correcting comments.

Maggie, who had echoed others’ ideas during PA1, accomplished the task by seeking help from peers and the teacher. At first, she spent time criticizing the assessee’s handwriting. She interpreted handwriting with Tara, asked Rachel for help, and then asked the teacher for help. Since in our opinion, the handwriting looked rather clear, we interpreted her criticism of it as an excuse to avoid the task and seek help with assessing. The teacher came to Maggie, calmly read and discussed the work with her, and encouraged her to write down her thoughts. This helped Maggie complete half the criteria, after which she again criticized the handwriting and asked Rachel, the researcher, and the teacher for help. Maggie was persistent in her attempts to provide feedback, and after a considerable struggle, she provided one encouraging comment and one suggestion for improvement. Maggie’s struggles became even more evident later, and this is depicted in the extract below, in which she was assessing her friend Tara’s lab performance.

34 | Maggie: | Tara, sorry, I can’t mark |

35 | that you correctly used the burner | |

36 | Tara: | But I did |

37 | Maggie: | You blew on it |

38 | Rachel: | Yes, you did (laughs), |

39 | and you, like, blew it out | |

40 | Tara: | I’m sorry, but my fingers almost burned |

41 | Rachel: | I wouldn’t have (indistinguishable) shaken |

42 | Maggie: | “Your working was thoughtful and controlled.” |

43 | Tara: | Really? |

44 | Rachel: | (Laughs) |

45 | Maggie: | I feel bad |

46 | (Asks the teacher) Can you mark two options | |

47 | if it’s in between? | |

48 | Like, it seems that it’s actually neither | |

49 | Teacher: | Either/or, preferably |

50 | Maggie: | But I think these, like, |

51 | Tara did otherwise good, | |

52 | but there was, like, one tiny thing |

During the inquiry, Tara lit the gas burner and blew the match out in front of it, blowing the burner out as well. The gas kept leaking out, spreading its distinctive smell across the classroom, and this caused minor chaos. When assessing Tara’s work, Maggie, quite justifiably, commented that she could not rate Tara’s burner use as “excellent” but only “good” (34, 35). Notable is that even though the assessment was formative, Maggie felt uncomfortable rating Tara as “good,” and in addition to explaining her decision to her (34–35, 37) and being supported by Rachel (38–39), she asked the teacher for help. For Maggie, providing criticism was laborious, but she was persistent, and with other’s support, she managed to do it. It was evident that Maggie did not lack the attitude (she strove to give a solid judgement) or skills (she knew that Tara’s performance was less than excellent) but rather the agency to put her knowledge into action. By seeking second and third opinions, she gained agency that enabled her to provide feedback she considered justified.

Nathan was Lucas’ group member and had echoed his ideas during PA1. Nathan seemed to struggle with providing feedback too, but his solution was the opposite of Maggie’s. Assessing the lab report took Nathan a substantial amount of time. On the recording, the sound of Nathan writing and erasing can be heard long after Lucas was done. He wound up marking each criterion with the best option (“Everything is ok”) and provided only one written comment: “What you needed was clearly explained.” It is possible that Nathan did not notice any of the several shortcomings in the lab report, but this seems unlikely, as providing trivial feedback took him such a long time. We suggest that Nathan noticed some problems and spent time thinking about how to react to them. During the year of practicing peer assessment, Nathan consistently avoided criticizing others’ work and independently gave only the highest marks and compliments. During PA3, when pairs assessed each other’s lab work, Lucas even corrected Nathan several times for providing him with feedback that was too positive. Apparently, providing criticism was not a satisfactory option for Nathan. Unlike Maggie, he did not seek help with assessing but kept on providing overly positive feedback.

4 Exercising Agency as an Assessee

Students had diverse ways of exercising agency as assessees; these are presented in Fig. 17.4 and followed by examples.

Lucas, who initiated constructive ideas during PA1, was a rapid reviser. After receiving feedback about his lab report (PA2), he read the feedback, quickly judged it, rejected part of its useful aspects, and made small-scale improvements to his lab report. Rachel, who also initiated ideas during PA1, operated in a similar way, but she was more careful and did not reject useful feedback. It seemed that both Lucas and Rachel experienced both providing and receiving feedback as appropriate and uncomplicated.

Nathan, who echoed ideas during PA1, appeared generally open to feedback and committed to using it for improvement. In PA2 (revising own lab report), Nathan’s immediate reaction after receiving the feedback was to ask the teacher’s opinion: “Teacher! Should I revise this?” He waited until the teacher came to see him. Nathan wanted to know whether the feedback was valid, which the teacher confirmed. They discussed the issue for a considerable amount of time, and after, Nathan revised his work independently, managing to improve it.

Maggie, who also echoed ideas during PA1, took the opposite approach to a similar situation. In the excerpt below, she reacts to corrective feedback.

35 | Maggie: | Look, I made a few mistakes in the text |

36 | It doesn’t matter. Small mistakes | |

37 | Tara: | What mistakes do you mean? |

38 | Maggie: | That hypothesis was about the distance, |

39 | not speed | |

40 | I guessed the distance here | |

41 | and not the speed, | |

42 | how fast it moved | |

43 | Tara: | Yeah |

44 | Maggie: | But it does not matter |

45 | I’m surprised that I was this good |

The feedback Maggie received—“the hypotheses was about distance, not speed”—could have been used to improve her work. She could have changed her hypotheses, or comment the mistake in her revisions. Maggie affirmed that she had made a mistake (35) but characterized it as a small one (36) that did not matter (36, 44) and instead concentrated on her general performance (45). She bypassed the criticism by congratulating herself, did not return to the topic, and did not revise her work. One could construe that she was unresponsive, but her explanation in an interview suggested otherwise.

Researcher: | Okay, okay. Were you motivated to make revisions since you considered that [work] was not so super, not quite superlative? |

Maggie: | It has always been really hard for me to accomplish something (indistinguishable) because I always think that I’m stupid and if I do something, it always seems bad. So it’s hard to begin to improve |

Maggie said that a lack of confidence in her own abilities held her back from making revisions. Under the surface of congratulating herself, she was uncertain of her skills. It appears that she did not have the agency to undertake her revisions.

5 Discussion

This study explored students’ actions during formative peer assessment and contributed to the literature by enhancing awareness of their agency during the exercise. We identified nine forms of agency (initiating, echoing, judging work, avoiding criticism, seeking help, appraising feedback, rejecting feedback, revising work, avoiding revision) in three roles that peer assessment provided (group member, assessor, assessee).

Closer investigation of students’ interaction revealed that peer assessment challenged the students unevenly. Throughout each assessment, Lucas and Rachel practiced the agencies of initiating, judging work, and appraising feedback without difficulty, while Nathan and Maggie exercised those agencies only when they received support. When working in groups, Nathan and Maggie participated only by echoing other students’ suggestions. When acting individually as an assessor, Nathan consistently avoided criticizing others by providing only positive feedback. Maggie was persistent in her aspiration to provide valid critical feedback, but she needed help to do so. By asking support from other students and the teacher, she gained the agency of judging other students’ work. As an individual assessee, Nathan needed help appraising feedback before he revised his work, whereas Maggie did not seek help and refrained from revising her work. The findings show that even all students were placed in the same classroom, undertaking the same task of assessing their peers, their challenges were unequal. We explain this by referring to the notions that experience builds agency (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998) and that students’ previous actions create expectations for their participation (Gresalfi et al., 2009). For students who generally initiate ideas, are active, and advise others, the assessor role is more familiar and their feedback more likely to be accepted by classmates. For them, peer assessment is a straightforward task. For others, assessing may require acting outside their accustomed role.

The operationalization of peer assessment, especially whether it was conducted individually or in groups, influenced the social suggestions that were available for students (Billett, 2006) and thereby the agencies that students exercised. When assessing and receiving feedback in a group (PA1), the agencies of initiating and echoing were practiced. Working in a group allowed struggling students to receive subtle support when assessing and receiving feedback, as they were able to echo other students’ initiatives. Individual peer assessments (PA2, PA3) forced students to be responsible for themselves, which created the need to ask for and offer help and caused some students to avoid the task.

The findings are highly significant for the practice of peer assessment. The requirement of agency sheds light on the effects of students’ individual attributes on peer assessment, which is thus far an unexplored area (Panadero, 2016), and it addresses the need to ensure appropriate support for students’ agency when they are requested to exit their comfort zones as assessors and assessees. With an understanding of the requirements of agency, teachers can be better equipped to provide support. They can listen to, confirm, and endorse students’ thoughts, guide them to discuss the issue with their friends, or open the subject to a classroom discussion. The finding also highlights the need to be careful with the use of unsupported individual peer assessment, since it can be highly stressful for students who struggle with their agency. Moreover, if teachers are not aware of the requirement of agency, they may misinterpret students’ misbehavior or underperformance as stemming from a lack of skills or a negative attitude. If teachers respond by assisting students in the accomplishment of their peer assessment tasks instead of strengthening their agency, they can weaken that agency by indicating students are not capable of acting as assessors and assessees on their own.

The finding about the requirement of agency has implications for peer assessment training. Peer assessment provides a platform for students to exercise agency in assessment and learning by guiding them to act in various, and potentially new positions in relation to other students. Hence, peer assessment can advance democracy in the classroom not just between teachers and students (Gielen et al., 2010) but also by sharing among everyone the responsibility to help others. However, helping others, especially in the form of criticizing and advising, cannot be taken for granted. Nineteenth century German pedagogue Froebel (1887) argued that “the purpose of teaching and instruction is to bring ever more out of man rather than to put more and more into him” (p. 279, emphasis in the original). The quote applies to students’ agency by describing a new aspect of peer assessment training. We agree with the necessity of providing students with knowledge, such as understanding the qualities of constructive feedback (Tasker & Herrenkohl, 2016), skills, such as judging received feedback (Carless & Boud, 2018), and attitudes, such as their sense of responsibility when assessing (Panadero, 2016). However, students’ agency also needs to be encouraged. As agency is seen as an interplay between an individual and their environment, training requires investing not just in individuals but also in their relationships and the culture of the classroom. We consider this a significant area for future research: how does peer assessment assist in transcending the classroom’s fixed patterns and strengthening students’ agency?

Technology can support the development of student agency (Marín et al., 2020). Technological environments are commonly used in peer assessment (see Fu et al., 2019). They are convenient for sharing work, matching students for peer assessment, and providing feedback, and they allow students to assess each other either anonymously or by name. The findings of this study suggest that the organization of peer assessment should be examined from the perspective of agency, which also concerns technological environments. First, how do different kinds of technological environments support students’ agency? Anonymity may provide students different kinds of social suggestions, a new role in which to operate, and hence a lower threshold at which to participate actively. Interaction has been suggested as an element that deepens the learning process of peer assessment, while anonymity is a feature that diminishes that interaction (Panadero, 2016). Technology allows students to interact anonymously, and the pros and cons of such arrangements for students’ agency are worth examination. Important aspect to consider is that students' agency must be supported in technological environments, one way or another. Students should not be left alone with their devices but be allowed to interact with each other and the teacher and to seek help during peer assessment. Technological environments can be interactive and allow students to seek help (e.g. Tasker & Herrenkohl, 2017). We consider the diverse ways of supporting students’ agency during peer assessment—both face to face and online—to be an important topic for future research.

This was a case study of four students, two of whom appeared to struggle with their agency during peer assessment, whereas the other two did not. The finding was consistent throughout all types of peer assessment during the school year. The merit of our study is that it introduces and demonstrates the requirement of agency during peer assessment. However, by selecting students who did not have apparent cognitive or motivational challenges, we have dealt with only part of the spectrum of forms of agency during peer assessment, and further research about the topic is needed. For example, what role does students’ social position in class play alongside their subject skills or confidence in mastering them, and what kinds of environments support students’ agency? Potentially, different types of challenges with agency require different types of support.

Our study showed that the concept of agency is useful in unveiling and explaining peer assessment’s underlying dynamics. Awareness of how students’ agency plays a role in peer assessment is significant to educators and researchers. Students’ reluctance or inability to help their peers or accept help do not necessarily stem from a lack of knowledge, skills, or attitude but can be suggestive of their difficulties in exercising agency.

Notes

- 1.

Transcription notations are described immediately below.

- ( ):

-

Description of context or nonverbal speech.

- “ “:

-

Reading text.

- —:

-

Comment was interrupted.

- …:

-

Words were cut out.

- [ ]:

-

Clarifies the reference.

The line numbers are group specific and start from “1” after each transition (i.e., each change to new work [PA1] or a change in assessor and assessee [PA1, PA2]).

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annual Review of Anthropology, 30, 109–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

Biesta, G., & Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: Towards an ecological perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39(2), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2007.11661545

Billett, S. (2006). Relational interdependence between social and individual agency in work and working life. Mind, Culture and Activity, 13(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1301_5

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Boud, D. (2014). Shifting views of assessment: From secret teachers’ business to sustaining learning. In C. Kreber, C. Anderson, N. Entwistle, & J. MacArthur (Eds.), Advances and innovations in university assessment and feedback (pp. 13–31). Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748694549.003.0002

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braund, H., & DeLuca, C. (2018). Elementary students as active agents in their learning: An empirical study of the connections between assessment practices and student metacognition. Australian Educational Researcher, 45, 68–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0265-z

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Charteris, J., & Thomas, E. (2017). Uncovering “unwelcome truths” through student voice: Teacher inquiry into agency and student assessment literacy. Teaching Education, 28(2), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1229291

Dawson, P., Henderson, M., Mahoney, P., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2019). What makes for effective feedback: Staff and student perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Foley, S. (2013). Student views of peer assessment at the International School of Lausanne. Journal of Research in International Education, 12(3), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240913509766

Froebel, F. (1887). The education of man. (W.N. Hailmann, Trans.). Appleton. (Original work published 1826).

Fu, Q.-K., Lin, C.-J., & Hwang, G.-J. (2019). Research trends and applications of technology-supported peer assessment: A review of selected journal publications from 2007 to 2016. Journal of Computers in Education, 6, 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-019-00131-x

Gielen, S., Tops, L., Dochy, F., Onghena, P., & Smeets, S. (2010). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback and of various peer feedback forms in a secondary school writing curriculum. British Educational Research Journal, 36(1), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902894070

Gresalfi, M., Martin, T., Hand, V., & Greeno, J. (2009). Constructing competence: An analysis of student participation in the activity systems of mathematics classrooms. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 70, 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-008-9141-5

Harris, L., & Brown, G. (2013). Opportunities and obstacles to consider when using peer- and self-assessment to improve student learning: Case studies in teachers’ implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.008

Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T., & Dargusch, J. (2018). Not playing the game: Student assessment resistance as a form of agency. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0264-0

Ketonen, L. (2021). Exploring interconnections between student peer assessment, feedback literacy and agency. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Jyväskylä].

Ketonen, L., Hähkiöniemi, M., Nieminen, P., & Viiri, J. (2020a). Pathways through peer assessment: Implementing peer assessment in a lower secondary physics classroom. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 18, 1465–1484. https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/76143

Ketonen, L., Nieminen, P., & Hähkiöniemi, M. (2020b). The development of secondary students’ feedback literacy: Peer assessment as an intervention. The Journal of Educational Research, 113(6), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2020.1835794

Kumpulainen, K., Kajamaa, A., & Rajala, A. (2018). Understanding educational change: Agency-structure dynamics in a novel design and making environment. Digital Education Review, 33, 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2018.33.26-38

Marín, V. I., Benito, de Benito, B., & Darder, A. (2020). Technology-enhanced learning for student agency in higher education: a systematic literature review. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal, 45, 15–49. https://doi.org/10.55612/s-5002-045-001

Matusov, E. (2011). Authorial teaching and learning. In E. J. White & M. Peters (Eds.), Bakhtinian pedagogy: Opportunities and challenges for research, policy and practice in education across the globe (pp. 21–46). Peter Lang Publishers.

Matusov, E., von Duyke, K., & Kayumova, S. (2016). Mapping concepts of agency in educational contexts. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 50(3), 420–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9336-0

Mok, J. (2010). A case study of students’ perceptions of peer assessment in Hong Kong. ELT Journal, 65(3), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq062

Nieminen, J. H., & Tuohilampi, L. (2020). “Finally studying for myself”: Examining student agency in summative and formative self-assessment models. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(7), 1031–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1720595

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). Validity and qualitative research: An oxymoron? Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 41(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9000-3

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: A review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Panadero, E. (2016). Is it safe? Social, interpersonal, and human effects of peer assessment: A review and future directions. In G. T. L. Brown & L. R. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of social and human conditions in assessment (pp. 247–266). Routledge.

Panadero, E., Jonsson, A., & Alqassab, M. (2018). Providing formative peer feedback: What do we know? In A. A. Lipnevich & J. K. Smith (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of instructional feedback (pp. 409–431). Cambridge University Press.

Sannino, A. (2015). The emergence of transformative agency and double stimulation: Activity-based studies in the Vygotskian tradition. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 4, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.001

Sluijsmans, D. M. A. (2002). Student involvement in assessment: The training of peer assessment skills. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Open University of the Netherlands, Heerlen. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-491x(03)90003-4

Tasker, T., & Herrenkohl, L. (2016). Using peer feedback to improve students’ scientific inquiry. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 27(1), 35–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-016-9454-7

Topping, K. J. (2009). Peer assessment. Theory into Practice, 48(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802577569

Topping, K. J. (2013). Peers as a source of formative and summative assessment. In J. H. McMillan (Ed.), SAGE handbook of research on classroom assessment (pp. 394–412). Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218649.n22

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., & Parker, M. (2017). “It’d be useful, but I wouldn’t use it”: Barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 2026–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032

van Gennip, N., Segers, M., & Tillema, H. H. (2009). Peer assessment for learning from a social perspective: The influence of interpersonal variables and structural features. Educational Research Review, 4, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2008.11.002

van Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D., & van Merriënboer, J. (2010). Effective peer assessment processes: Research findings and future directions. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ketonen, L., Nieminen, P., Hähkiöniemi, M. (2023). How Do Lower-Secondary Students Exercise Agency During Formative Peer Assessment?. In: Noroozi, O., De Wever, B. (eds) The Power of Peer Learning. Social Interaction in Learning and Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-29410-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-29411-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)