Abstract

Higher education institutions are increasingly implementing peer tutoring and peer mentoring strategies to support newly enrolled students’ transition into university, aiming to reduce drop-out and improve persistence. However, it is rare that these are directly compared, and even rarer for effects on social and academic integration and institutional attachment to be explored, as in this study. In this quantitative and qualitative study, a total of 446 first-year university students of Psychology and Education Sciences in one university, recruited via a snowball technique which relied heavily on email and text messages, followed-up with invitations to a Facebook group, completed an online questionnaire. The questionnaire incorporated three instruments of known reliability: the Social Adjustment, Academic Adjustment and Institutional Attachment subscales of the Adaptation to College Questionnaire; the Commitment subscale of the Revised Academic Hardiness Scale; and the Commitment Attitude Scale. Results were analysed by independent t-tests. For the qualitative semi-structured interviews participants were 39 self-selected but stratified volunteers. Interviews focused on the three stages of Appreciative Inquiry: Discovery, Dream and Design. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. A combined inductive-deductive content-analysis technique and a thematic analysis technique was then used via MAXQDA 11. Peer mentoring was the most effective means to enhance social integration. However, peer tutoring showed a significant effect on academic integration. Neither had much impact on institutional attachment. Participants particularly mentioned that activities such as speed dating and mentoring days were important, since they developed self-esteem, which encouraged them to further participate. The availability of peer support over the longer term was seen as important. Evidence-based action implications for educational practice, policy-making and future researchers were outlined, and the importance of listening to students when developing institutional policy is emphasized.

The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, Department of Education, through a grant from the Central University Department of General Strategy Planning at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- University

- Peer mentoring

- Peer tutoring

- Social integration

- Academic integration

- Institutional attachment

- Perceptions

1 Introduction

The educational agenda is more than ever dominated by heightened demands on student attraction, retention and graduation (Vossensteyn et al., 2015). Newly entering students increasingly struggle with issues related to their transition and adjustment to university education (Berger et al., 2012; Hagedorn, 2006; Tinto, 2003, 2010). The lack of opportunities for safe and frequent social interaction hinders newcomers’ socialisation and learning (Lowe & Cook, 2003; Wu, 2013). This is particularly true for those who commute to university, work and/or attend part-time (Gillies & Mifsud, 2016).

Higher education institutions internationally are increasingly implementing various peer tutoring and peer mentoring strategies to support newly enrolled students’ transition into university, aiming to reduce drop-out and improve persistence. More and more studies report significant outcomes from such initiatives in student integration, commitment or persistence (e.g., Andrews & Clark, 2009; Pleschová & McAlpine, 2015). However, it has been relatively rare for different systems to be directly compared within the same institution.

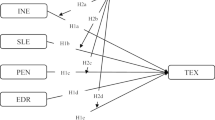

This chapter investigates the impact of different strategies on opportunities for social development and academic learning in the first year of higher education in one university. Student-to-student interactions were developed face-to-face and technology was used to increase students’ initial and continued participation. The aim was twofold: (1) to examine and compare the effects of peer mentoring and peer tutoring on students’ perceptions of their social integration, academic integration and persistence; (2) to explore which aspects of each intervention students considered successful or otherwise, and explore suggestions for improving effectiveness.

2 Previous Research

Studies show that the more students are academically and socially involved, the more likely they are to persist and graduate (Tinto & Pusser, 2006). Fostering students’ integration has become an important educational objective, certainly since adequate academic integration is often considered to deepen learning and is correlated with more active cognitive processing, better understanding and improved performance (Torenbeek, et al., 2010; Zepke, et al., 2006).

Also emphasized in research is the role of student support and needs-based aid for university students’ social and academic integration, particularly in the first year of study (Astin, 1993; Carter, et al., 2013; Tinto, 2003) and achievement (Crosier, et al., 2007; Dukakis, et al., 2007). The literature contains many recommendations of strategies and initiatives that support students in becoming more active participants in all facets of university life (Tinto & Pusser, 2006). Researchers recently suggested that peer tutoring and mentoring are effective and relatively simple ways for students to become more active members of the university community (Rayle & Chung, 2008; Torenbeek, et al., 2010; Wilcox, et al., 2005).

As a working definition, we adopt that of Topping et al. (2017), i.e., peer tutoring is “people from similar social groupings who are not professional teachers helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching” (p. 10). It is characterized by specific role-taking and high focus on curriculum content. By contrast, Topping’s definition of peer mentoring is “an encouraging and supportive one-to-one relationship with a more experienced worker (who is not a line manager) in a joint area of interest, characterized by positive role modelling, promoting raised aspirations, positive reinforcement, open-ended counselling and joint problem-solving” (Topping & Ehly, 1998, p. 9). It engages with broader issues than curriculum content. Both students benefit when they are able to help each other (Copeland, et al., 2002).

Previous research provides empirical support for the positive effects of peer tutoring in diverse instructional settings with outcomes ranging from cognitive and meta-cognitive gains to affective and social-motivational benefits for both peer tutors and tutees (Falchikov, 2001; Topping, 2005). Peer tutoring participants demonstrate better performance and higher academic achievement (Bronstein, 2008; Fayowski & MacMillan, 2008; Ning & Downing, 2010; Peterfreund et al., 2007). These often come from improved understanding of content (Dobbie & Joyce, 2008; Smith et al., 2007; van der Meer & Scott, 2009), critical thinking (Stigmar, 2016), transfer and autonomy of learning (Stigmar, 2016), profound knowledge-construction after applying deeper and strategic learning strategies (Dobbie & Joyce, 2008; Smith et al., 2007; van der Meer & Scott, 2009) and development of transferable academic skills (Court & Molesworth, 2008; Ning & Downing, 2010). Students perceive peer tutoring settings as safe learning environments that stimulate tutors’ and tutees’ self-confidence (Ford, et al., 2015), heighten their wellbeing (Bronstein, 2008), and lower any uncertainty (Court & Molesworth, 2008).

Additionally, peer tutoring appears to result in higher motivation (Stigmar, 2016) and connectedness (Dobbie & Joyce, 2008; Smith et al., 2007; van der Meer & Scott, 2009), as well as increased academic satisfaction (Robinson et al., 2005). Peer tutoring participants further report social benefits (Court & Molesworth, 2008) and improved communication behaviour (Ford et al., 2015). Although positive effects on students’ retention are reported (Bronstein, 2008; Peterfreund et al., 2007), these cannot always be confirmed in other studies (e.g., Carr et al., 2016). By contrast, research clearly confirms students’ appreciation of peer tutoring, both when providing and when receiving academic help (Ginsburg-Block, et al., 2006; Griffin & Griffin, 1998; Topping et al., 1997).

During the last decade, educational research has also provided empirical support for the positive effects of peer mentoring in higher education settings, including performance, intellectual and skills gains but also emotional benefits and other non-cognitive results for both peer mentors and mentees (Outhred & Chester, 2010). Peer mentoring participants demonstrate better performance (Amaral & Vala, 2009; Fox, et al., 2010; Goff, 2011; Smith, 2009) and higher academic knowledge (Bullen et al., 2010). By providing positive role models for the students (Lahman, 1999; Twomey, 1991), peer mentoring is often related to increased development of values and skills (Bullen et al., 2010; Hall & Jaugietis, 2010), as well as more profound listening skills (Lee et al., 2010). As a result of working and socializing with peers, students’ participation in classes and extra-curricular activities is higher (Bittich & Rongen, 2007; Copeland, et al., 2002) and they are academically and socially more integrated (Elster, 2014; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005).

What sort of tasks provided the context for peer interaction? In peer tutoring the tasks were determined by the tutee but drawn from the curriculum context set by the instructors, and in that sense were more aligned to the instructional design literature (Biggs, 1996). In peer mentoring the tasks were those the mentee chose to raise according to the extent to which they were concerning, and in this sense related more to constructivist learning theory (Biggs, 1996), a family of theories all having in common the centrality of the learner's activities in creating meaning. Biggs’s notion of “constructive alignment” sought to marry the two thrusts of instructional design and constructivism. Likewise, Wenger invented and then explored the concept of “community of practice” (Farnsworth et al., 2016), conceptualising identity and participation in order to develop a social theory of learning in which power and boundaries are inherent. This clearly relates to a context in which peers form communities in which interaction with each other regarding social and academic objectives and problems is regarded as natural.

As peer interaction strategies became more widespread and popular (Duron, et al., 2006), more diverse programmes and formats appeared, as well as new lines of research (Maheady & Gard, 2010; Maheady, et al., 2006; Roscoe & Chi, 2007). Peer interaction is becoming increasingly significant (Aljohani, 2016; James, et al., 2010; Muldoon & Wijeyewardene, 2012), and has become key for both the acquisition of innovation and creativity (Johansson, 2004) and interdisciplinary thinking (Johansson, 2004). Spontaneous forms of peer interaction might have potential that seem to be underestimated or underused. By taking a focus on peer interaction in informal learning environments and outside-class contexts, particularly during the first semester at university, in this study we contribute to current research.

In the literature, the concept of student integration is mostly discussed via environmental and (symbolic) interactional theories of social and academic integrative learning (Tinto, 1993). In contrast to the notions of cognitive development (e.g., Piaget, 1987), learning is conceived of as a collective process of maturation (Burgess, 2016). People are perceived as active agents and contributors to social life, with the ability to negotiate, share and create a distinct peer culture in collusion with other ‘more experienced’ others (Corsaro, 2005) to absorb the norms and values of the surrounding society (Burgess, 2016). “The more students are academically and socially engaged, the more likely they are to succeed. Such engagements lead not only to social affiliations and the social and emotional support they provide, but also to greater involvement in learning activities and the learning they produce. Both lead to success in the classroom” (Tinto, 2006).

Integrative learning, as recently formulated by Tinto (2012), focuses attention on the integration and translation of academic spheres and divergent domains of knowledge, culture, and social practice. According to Tinto (2015) “academic integration is the extent to which students adapt to the academic way-of-life.” (Tinto, 1993). Academically well-integrated students have the willingness to belong to a group and the ability to belong to one (Severiens & Wolff, 2008). Social integration is the degree to which students adapt to and familiarize themselves with the social university environment (Rienties et al., 2012). Successful socially-integrated students have many friends at university, feel at home, take part in extra-curricular activities and feel connected to fellow students and teachers (Bittich & Rongen, 2007; Severiens & Wolff, 2008).

Consequently, while the present study will discuss both academic and social integration in university, the main focus will be on social integration and its cross-over effects on academic integration.

3 Method

3.1 Design

The study used a sequential, mixed-methods design (Creswell & Clark, 2011), which was intended to maximise participation and triangulate findings. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected throughout the years with students registered for the first-time in the first year of a bachelor programme at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, at a Dutch-speaking university in a large city in the north of Belgium, in three consecutive academic years. A clear control design could not be used due to ethical considerations. Therefore, a non-randomised control group of non-participants was formed for all comparisons. The design was thus quasi-experimental.

3.2 Sample

We invited all 842 students to volunteer to participate in the survey, and of these 731 (87%) eventually completed the survey. From these 731 students, students who had been studying for more than one year in the faculty (n = 285) were removed from the student population because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. In the end, a sample size of 446 (61%) unique students were included. The sample population of first-year students were 26% in the Department of Educational Sciences (N = 115) and 74% in the Department of Psychology (N = 360). The majority (65%) were registered for the first time in a bachelor degree programme in higher education (N = 291). There were four times as many female students (81%; N = 360) as male students (19%; N = 86).

Participants were recruited via a snowball technique which relied heavily on email and text messages. First students were invited face-to-face to complete the survey. Then we asked them by email and via the e-learning platform. After three weeks, the students received a reminder. After six weeks, the students who did not fill in the survey were personally reminded by email. After nine weeks, the students who still did not fill in the survey were personally reminded by mobile phone text message. This was followed-up with invitations to a Facebook group. In this way, students who would not have noticed traditional messaging participated, and the number of participants was close to the total numbers in these departments.

For the qualitative follow-up semi-structured interviews, participants were 39 self-selected volunteers stratified from each of the peer interaction initiatives. Of the 39 respondents, 23 (59%) were students who participated in peer mentoring, and 20 (51%) were students who participated in peer tutoring. Academic disciplines were almost equally divided between psychology (49%; N = 19) and educational science (51%; N = 20). There were three times as many female students (74%; N = 29) as male students (26%; N = 10).

3.3 Measures

In the quantitative part, data collection involved the development, delivery and collection of online questionnaires using the Qualtrics software. Surveys were administered at the start of the second year to investigate newcomers’ perceptions after one year of experience of higher education. In the qualitative part, individual in-depth interviews with first-year students who participated in peer mentoring or peer tutoring or both were conducted in order to obtain a deeper understanding of their experiences.

The online questionnaire incorporated measures of social integration, academic integration, academic commitment, commitment attitude and institutional attachment. Three instruments of known reliability were administered: the Social Adjustment, Academic Adjustment and Institutional Attachment subscales of the Adaptation to College Questionnaire (Baker & Siryk, 1989); the Commitment subscale of the Revised Academic Hardiness Scale (Benishek, et al., 2005); and the Commitment Attitude Scale (Solinger, et al., 2015). A seven-point Likert scale, on a continuum ranging from 1 (does not apply to me at all) to 7 (applies to me very well) was used. The subsequent reliability of these measures (Cronbach’s Alpha) was high for Social Integration and Social Adjustment (0.90), Social Engagement (0.83) and Institutional Attachment (0.82), but less so for Academic Integration and Motivation (0.74), Academic Application (0.75) and Academic Performance (0.80).

Interviews were based on the three stages of Appreciative Inquiry (AI): Discovery, Dream and Design (Barrett, 1995; Cooperrider, et al., 2003; Whitney & Trosten-Bloom, 2010). AI is an innovative participative research approach (Czarniawska-Joerges, 1996) that differs from other current research methodologies (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987) by its affordance of a positive, holistic and appreciative lens. It “involves a wondering that can touch the soul” (Kung, et al., 2014). Through its focus on successes and their potential influences in co-creating desired futures, it opens participants’ experiences in a generative manner towards ongoing and deepening reflections and move deficit discourse towards deep engagement and contemplative insight within oneself and with others (Kung, et al., 2014). As a form of social constructivist evaluation, AI aims to enable those involved in evaluation to make sense of educational change through dialogue, reflection and interaction.

The interview instrument included only open-ended questions. The first questions to be posed (discovery) asked the participants to focus on their stories of best practice, positive moments, greatest learning and successful processes related to their experiences with one of the activities in which they participated. They were then asked to ‘dream’ about how those kinds of support systems could be even better (Watkins & Mohr, 2001). Particular attention was paid to asking reflective AI questions related to the question ‘when’: “the first four weeks”, “after one month” and “in the last four weeks”. The researcher in the first phase (‘discovery’) asked the participants to focus on particular experiences that they would describe as being positive and life-centric in nature and to share the essence of their stories as a means of remembering specific practices, events, processes. In the second phase (dream), she asked them to ‘dream’ about how it could be even better (Watkins & Mohr, 2001) and imagine an ideal future. In order to determine the strategies to assist them in realising common needs, during the last phase (‘design’) the researcher encouraged the participants to think about their expectations related to actions and decision in order to make the vision become reality, in the form of an action plan for future practice.

3.4 Analysis

The questionnaire data were summarised in SPSS and subjected to analyses seeking to determine whether the responses were statistically different from a random distribution. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by one researcher. Verbatim quotes of frequently occurring issues were documented with hand-written notes by the interviewer throughout the interview process. To help reduce socially desirable answers, each AI phase began with a one-minute independent writing activity in which individual responses related to the open-ended questions were documented with hand-written notes by each participant. The interviews lasted 20–30 min and each question lasted around 3 min. A combined inductive-deductive content-analysis technique was coupled with a thematic analysis technique. One coder reviewed all the interviews twice. MAXQDA 11 was used to analyse the data. In the results we indicate frequency of response themes, providing illuminative quotations.

Analysis of interviews was based on the transcripts, hand-written detailed reports of the researchers and the handwritten one-minute preparations of the students. The transcripts were all conjointly analysed by two researchers using thematic analysis technique, identifying “powerful” themes (van Manen, 1990) in relation to the participants’ life-centric experiences using MAXQDATA. This programme had the advantage of making the process of axial coding easier by ordering, dividing and clustering codes into categories, and recognizing structures or patterns. The phases were analysed separately. Inter-rater reliability exceeded 90% (Miles et al., 2018), and informal discussions ensured consensus. We used Hycner's (1985, 1999) systematic procedures to identify essential features and relationships: repeatedly reading each interview, identifying statements of research phenomena, grouping units of meaning to identify significant topics or central themes, checking back with the data to ensure the content had been correctly captured, summarising the transcript of interview, and identifying “themes common to most or all of the interviews as well as the individual variations” (Hycner, 1999), and writing a composite summary.

3.5 Technology

Quite apart from the extensive use of technology in the sampling process, it tended to be less important at the beginning when students lacked self-esteem. However, as peer interaction activities developed, technology became more and more important. Later, social media (especially Facebook) played an important role. Indeed, social networking media became indispensable for some. Not only were they used to build friendships and maintain social relations, they were also used to process subject matter and exchange summaries. It was striking that the fear of feelings of loneliness and anxiety were very prominent among certain students.

Technology also had a role in academic integration. Learning did not exclusively take place during particular activities (e.g., revising for an exam) or in particular environments (e.g., the classroom), but was embodied in social environments and everyday life. Higher-year students could, for instance, help with administrative tasks, system navigation or educational knowledge later in the year (e.g., for examinations), by delivering relevant information in consolidated timely bursts via text messages, Facebook groups and emails. Students were involved in a range of community groups, physical places, virtual spaces and social networks in relation to their personal interests. These networks were individually selected by students, shaped and re-negotiated, and spread across physical spaces, friends and peer groups, as well as virtual spaces and online learning platforms.

Thus, there was no direction regarding which applications to use for maintaining contact, and indeed no way in which the institution could sensibly control this. Fashionable applications for exchanging messages change quite quickly, and the students needed to use those for which they were motivated and with which they were familiar. There was no way the institution could keep up with this, and issues of digital ethics could not be policed. Indeed, the fact that such applications clearly belonged to the students and were not part of the institution probably added to the sense of “community of practice”. Of course, this may raise issues of privacy, equality and responsibility.

4 Results

4.1 Quantitative

Peer mentoring participants reported a significantly higher level of social adjustment and social engagement than nonparticipants (t = −2.480, df = 425, p < 0.05). Mentoring participation had a moderate effect on social adjustment (Effect Size d = 0.370) and had a small effect on the difference in social engagement (Effect Size d = 0.315). There were also clear differences between participant and non-participant group scores on peer tutoring, with participants achieving a higher average level of social adjustment and social engagement than non-participants, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. For academic integration, there was a slight difference in the level of academic motivation, academic application and academic performance between participants and non-participants of peer mentoring, but none of these was significant. An independent samples t-test showed that for students who participated in peer tutoring, academic application scores appeared to indicate a marginal significance for the difference between the participation groups (t = −1.715, df = 429, p < 0.1). Participation in peer tutoring thus had a small effect on academic application (Effect Size d = 0.306). The differences in average institutional attachment scores between participants and non-participants in peer mentoring were not significant. Although peer tutoring students showed a higher level of institutional attachment compared to non-participants, the differences were not significant.

Thus, as far as the survey data could tell us, peer mentoring appeared better for social integration, peer tutoring appeared better for academic integration, and neither appeared to affect institutional attachment.

4.2 Qualitative

Taking peer mentoring first, almost two-thirds of the respondents who participated in peer mentoring claimed that they had a connection with a higher-year student, and more than one-quarter indicated that they had built up friendships. Over half of respondents saw speed dating as very valuable. They claimed that such activities were fundamental contact-making mechanisms between new students which could become sustainable. Over half of respondents claimed that due to peer mentoring they had a connection with the student community and believed that a certain level of similar interests in psychology and human development, together with taking the same courses and/or study/life path, was what bound students together. This is clear in this quote:

I’m always coming back to the same conclusion: to get connected with the right people. Those students who have the same effort and energy or willingness as you have. (Student 164: woman, first-time, regular student, large group learning context - LGLC).

The speed-dating activities were reported as an effective strategy for networking and searching for a mentor. Less than half of the respondents commented that this was due to the possibility of meeting different students at different times and in a structured manner. One respondent clearly describes this:

It was good to keep some activities simply cosy; so that people can have simply a talk with each other, enjoying their time, and having fun is paramount. This breaking-the ice is almost everything. So that is also very important. (Student 185: woman, first-time, regular student, small group learning context - SGLC).

Almost two-thirds of the respondents were satisfied with peer mentoring because they were given the opportunity to get in touch with higher year students as well as students of the same year and the same study programme. They saw this as a unique opportunity to build trust and more personal relationships with those who were willing to share expertise and experiences with each other in common:

The peer mentoring walks to the centre of Brussels are very captivating because then you get to know each other better, build up a connection. The development of this bonding is important to gain trust in each other, and to enable you to share your problems or difficulties more easily and immediately, or to ask for help if you do not understand course contents. (Student 154: woman, first-time, regular student, SGLC).

For almost two-thirds of the respondents, connecting with higher-year students in their own department was the reason for valuing their experience with peer mentoring. This was also evident in this quotation:

If you are fretting for weeks, then you have someone you trust and you can call on, and you don’t have to think, for example, ‘who should I now badger again with my troubles? They shouldn’t have time for me,’ therefore. (Student 143: woman, first-time, regular student, LGLC).

Because students experienced pleasure and value with their mentors during peer mentoring, they often also spent their free time together. Almost two-thirds of the respondents claimed that such activities were necessary especially for those who were interested in getting involved in social life on campus and wanting to get in touch with peers with whom they could discover life on campus. Almost all mentioned that peer mentoring enabled them to experience the power of social interactions with experienced peers who had recently taken the same path:

This is imperative for me. Because if you are befriended with higher-year students, you are closer to them and you get more help. It makes you feel better about yourself, and feel safer and more relaxed if you have someone around. And in turn, you will also provide more help to others, which again increases your wellbeing. So yes, these relationships determine if I’m satisfied and experience a certain level of happiness or not, and this consequently predicts the extent to which I will be happy and satisfied with my study and study situation. (Student 185: woman, first-time, regular student, LGLC).

Turning to peer tutoring, nearly all the respondents asserted they connected with other classmates with whom they had the same social learning experience. Almost half of the respondents saw peer tutoring’s focus on courses such as ‘Logic’ and ‘Statistics’ as very valuable. They claimed that such focus on difficult courses was a fundamental binding mechanism between new students:

At the beginning of the year, you cannot really imagine how you will pass this course. Further experiences with fast-paced teaching professors and difficult, challenging courses just strengthened this first impression. In such a context, when the understanding of the content and the intent to persist fully becomes the responsibility of the student, peer tutoring makes a big difference when shared learning experiences were provided. (Student 127: man, first-time, regular student, SGLC).

A certain degree of willingness to be involved and persist in learning is what attracted students to peer tutoring and what bound them together, creating the sense of safety needed to start a conversation, to help each other, and to work together. Experiencing the effectiveness of social learning and collaborative colleague support was invariably appreciated by most respondents. The satisfaction that arose from getting the opportunity from the start of their study careers to make contact with their classmates who were open to share experiences was common: peer tutoring was of particular importance for first-year students to increase their social engagement in the faculty.

Experiences like those in peer tutoring enhance the willingness to interact and to share and to help other members of the faculty. As a student in the third year of the academic bachelor (programme), you can also experience difficulties. Peer tutoring is then also highly relevant. (Student 193: woman, first-time, regular student, LGLC).

Approximately one third of the respondents said that the way they experienced enjoyment with their classmates during the peer tutoring sessions led them to spend more time together to learn. Over two-thirds of the respondents reported that peer tutoring was particularly needed for those interested in the academic challenge of studying. The majority of the respondents indicated that typical, whole-class tutoring at many educational institutions could not match peer tutoring because the latter empowered learning and social integration:

When you enter university, you hardly know anybody. So, peer tutoring for Logic was great; I had just arrived and in no time at all everybody was helping each other. There were higher-year students who were engaged in facilitating the sessions and helping us with difficulties. We were searching for the correct answers together. This provided us with an opportunity to experience positive interactions with classmates and to build up relationships with more sustainable potential friendships. (Student 169: woman, first-time, regular student, LGLC).

That peer mentoring also had an impact on students’ institutional attachment was evident from the interviews. Almost invariably, peer mentoring was emphasized as crucial for the initial decision of students to study at university. The attachment to university that arose was common among many respondents:

It makes the university unique in this way. And, also, the competitive position with respect to other universities. They do not offer a support network of senior students of the faculty or where you can get a mentor scheme. Then you know in particular that you have a safety net. This was and is very important for me. And this is also the reason why students choose this university. (Student 154: woman, first-time, regular student, SGLC).

Respondents who participated in peer mentoring indicated that they now felt more attached to the university and were more motivated to remain enrolled. The role of peer mentoring in promoting counselling and finding informal expertise became clear:

The antisocial atmosphere and my roommates, they were the reason why I felt depressed. This period was really hard for me. Imagine, you come home from the lessons, but they do not interest you anymore. You cannot motivate yourself to study, and you are all alone, miserable. If my mentor was not with me, I think that would be the reason why I no longer lived in the dorms and why I left university. (Student 177: woman, first-time, regular student, LGLC, SA).

5 Discussion

5.1 Summary

Results indicated that peer mentoring (as compared to peer tutoring) was the most effective and efficient means to enhance social integration. Participants particularly mentioned that activities such as speed dating and mentoring days were important, since they brought them into contact with classmates and senior students and provided more opportunities for further social interaction. Participants mentioned the potential of such methods, since through this they could build up self-esteem, which stimulated students to ask questions of higher-year students and participate in other cross-age peer mentoring programmes. Although peer tutoring was not as effective in social integration, it was significantly important in relation to academic integration. However, participants emphasised the importance of class-based peer mentoring for social and academic integration, because classmates would experience the same study trajectory for the following three years. The availability of support over the longer term was seen as important. Using out-of-campus locations, appreciation-based narratives, and regular class-based social events were identified as examples of best practice.

5.2 Limitations

The use of a single cohort of psychology and educational students from one university inevitably raises limits on the transferability of the findings to other institutions and student groups. Nevertheless, triangulating data through questionnaires and interviews has provided rich descriptions and will raise the validity and credibility of the findings (Cresswell & Miller, 2000). Another important limitation is the absence of randomly selected controls for dealing with variables. The fact that we did not check for the multilevel effects of students being nested within the class groups is another limitation. A further limitation is that we did not enter covariates such as gender, age, socio-economic status or migration background to assess effects of variables other than contextual ones. Nor did we check the effects of implementation fidelity of the intervention as this was not the aim of the study. The dependent variables were only capturing self-reported data, sometimes recalled from previous integration experiences. Not all students can remember events accurately or completely. Finally, the degree of differences between participants and non-participants could have originated from inter-individual differences at start. These differences might be the result of selection bias.

6 Relationship to Previous Research

Firstly, concerning peer mentoring, it was further evident from students’ comments that it was not primarily higher-year students who were responsible for creating the benefits for social integration, but it was particularly activities such as speed dating and mentoring days that helped bring them into contact with classmates and eased them into social integration. This is partly in line with Daloz and Holt's (1988) suggestion that peer mentoring organisations need to set up social events for those participating in the programme, as these events provide opportunities for increased social interactions between mentors and mentees. The findings of this study showed that that such events provide more opportunities for social interactions between mentors and mentees. Secondly, it was further evident that students who reported the most beneficial experiences with peer mentoring were mainly those who belonged to student organisations or lived nearby or close to their mentor (either on campus or at home). Since the development of social relationships is correlated with regular and frequent meetings between mentor and mentee, this finding is not surprising (Colvin, 2007; Cornelius, et al., 2016). Indeed, it reveals some of the factors related to the problems inherent in building Wenger’s “communities of practice” (Farnsworth, et al., 2016).

Secondly, results indicated that students’ social integration between those who participated in peer tutoring and those who did not were not significantly different. Some respondents stated it was relatively hard for first-year students to make connections and work collaboratively together when social connections were not promoted in initial phases. Students needed to make connections assertively and to try to find someone at a similar stage of progress and achievement level in order to get the most help out of these contacts and to experience collaborative learning positively. In this respect, firstly, it is suggested that it should help for facilitators to encourage students to spend a few moments socialising with each other before each session begins. Future research needs to clarify whether or not this makes any difference to social integration outcomes.

Thirdly, it is argued that the development of social relations can be fostered by making connections and making students’ needs or abilities apparent to peers: these needs and abilities being topics with which students need help, or for subjects where students want to provide help, for example. This finding fits in with recent research that peer tutoring activities must incorporate some means of ensuring that tutees and tutors are well matched (Evans & Cosnefroy, 2013). This closely relates to what Ito et al. (2013) recently described as connected learning, which aims to support interest-driven activities, whereby learning is driven through social interactions with other like-minded people. As such, peer tutoring is based on connected learning principles, because students can exchange experiences and make friends—a promising approach to promoting both social and academic integration and learning in the first year of university (Rayle & Chung, 2008).

Our study confirms previous findings from Sosik and Godshalk (2000), which also suggested that age, gender, ethnicity, language preferences and education need to be taken into consideration. It also confirms findings from Bozeman and Feeney (2007), further suggesting that having similar backgrounds, interest and life experiences should be taken into consideration when pairing mentors and mentees.

7 Conclusion

This study extends prior research by exploring the potential influence of peer mentoring and peer tutoring on social integration, academic integration and institutional attachment with first year students. Using a mixed methods approach involving both quantitative and qualitative methods, the study compared the impact of both peer tutoring and peer mentoring approaches. Results indicated that friendship resulting from the accelerating integration was created in both groups of peer mentoring and peer tutoring participants. Both experienced informal learning in contrast to other non-participating students who did not create such friendships. However, peer mentoring seemed more powerful in terms of effects on social integration and peer tutoring was more powerful regarding academic integration. Another important conclusion of our study is that as spontaneously indicated by the students, both peer mentoring and peer tutoring increase self-esteem. There are thus evidence-based action implications for educational practice, policy-making and future researchers. It will be important in planning future strategies to enhance social and academic integration and institutional attachment that student opinions are firmly taken into account.

References

Aljohani, O. (2016). A comprehensive review of the major studies and theoretical models of student retention in higher education. Higher Education Studies, 6(2), 1–18.

Amaral, K. E., & Vala, M. (2009). What teaching teaches: Mentoring and the performance gains of mentors. Journal of Chemical Education, 86(5), 630–633.

Andrews, J., & Clark, R. (2009). Peer mentoring in higher education: A literature review. (CLIPP working paper series; Vol. 109). Aston University.

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. Jossey-Bass.

Baker, R. W., & Siryk, B. (1989). Student adaptation to college questionnaire (SACQ). Western Psychological Services.

Barrett, F. J. (1995). Creating appreciative learning cultures. Organizational Dynamics, 24(2), 36–49.

Benishek, L. A., Feldman, J. M., Shipon, R. W., Mecham, S. D., & Lopez, F. G. (2005). Development and evaluation of the revised academic hardiness scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 13(1), 59–76.

Berger, J. B., Ramírez, G., & Lyon, S. (2012). Past to present: A historical look at retention. In A. Seidman (Ed.), College student retention: Formula for student success (pp. 7–34). Rowman & Littlefield.

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32, 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

Bittich S., & Rongen L. (2007). Factoren voor studiesucces, rapport deskresearch en QuickScan. In Model-beleidsplan ter bevordering van sociale integratie in hogeschoolopleidingen. Hogeschool Zeeland.

Bozeman, B., & Feeney, M. K. (2007). Toward a useful theory of mentoring: A conceptual analysis and critique. Administration & Society, 39(6), 719–739.

Bronstein, S. B. (2008). Supplemental instruction: Supporting persistence in barrier courses. Learning Assistance Review, 13(1), 31–45.

Bullen, P., Farruggia, S. P., Gómez, C. R., Hebaishi, G. H. K., & Mahmood, M. (2010). Meeting the graduating teacher standards: The added benefits for undergraduate university students who mentor youth. Educational Horizons, 89(1), 47–61.

Burgess, M. (2016). The ‘whole of the wall’: A micro-analytic study of informal, computer-mediated interaction between children from a marginalised community. Newcastle University.

Carr, S. E., Brand, G., Wei, L., Wright, H., Nicol, P., Metcalfe, H., & Foley, L. (2016). Helping someone with a skill sharpens it in your own mind: A mixed method study exploring health professions students’ experiences of Peer Assisted Learning (PAL). BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 1–48.

Carter, D. F., Locks, A. M., & Winkle-Wagner, R. (2013). From when and where I enter: Theoretical and empirical considerations of minority students’ transition to college. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 28). Springer.

Colvin, J. W. (2007). Peer tutoring and social dynamics in higher education. Mentoring & Tutoring, 15(2), 165–181.

Cooperrider, D. L., & Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 1(1), 129–169.

Cooperrider, D. L., Whitney, D. K., & Stavros, J. M. (2003). Appreciative Inquiry handbook. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Copeland, S. R., McCall, J., Williams, C. R., Guth, C., et al. (2002). High school peer buddies. Teaching Exceptional Children, 35(1), 16.

Cornelius, V., Wood, L., & Lai, J. (2016). Implementation and evaluation of a formal academic-peer-mentoring programme in higher education. Active Learning in Higher Education, 10(1), 7–25.

Corsaro, W. A. (2005). The sociology of childhood. Pine Forge Press.

Court, S., & Molesworth, M. (2008). Course-specific learning in peer assisted learning schemes: A case study of creative media production courses. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 13(1), 123–134.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 1–130.

Crosier, D., Purser, L., & Smidt, H. (2007). Trends V: Universities shaping the European Higher Education Area. European University Association.

Czarniawska-Joerges, B. (1996). Book review: Realities and relationships. Soundings in social construction by K. J. Gergen. Scandinavian Journal of Management, (12)4, 468–470.

Daloz, L. A., & Holt, M. E. (1988). Effective teaching and mentoring. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 36(1), 28–29.

Dobbie, M., & Joyce, S. (2008). Peer-assisted learning in accounting: A qualitative assessment. Asian Social Science, 4(3), 18–25.

Dukakis, K., Bellm, D., Seer, N., & Lee, Y. (2007). Chutes or ladders. Creating support services to help early childhood students succeed in Higher Education. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California at Berkeley.

Duron, R., Limbach, B., & Waugh, W. (2006). Critical thinking framework for any discipline. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 17(2), 160–166.

Elster, D. (2014). First-year students’ priorities and choices in STEM studies—IRIS findings from Germany and Austria. Science Education International, 25(1), 52–59.

Evans, L., & Cosnefroy, L. (2013). The dawn of a new professionalism in the French academy? Academics facing the challenges of change. Studies in Higher Education, 38(8), 1201–1221.

Falchikov, N. (2001). Learning together: Peer tutoring in higher education. Routledge Kegan Paul.

Farnsworth, V., Kleanthous, I., & Wenger-Trayner, E. (2016). Communities of practice as a social theory of learning: A conversation with Etienne Wenger. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64(2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2015.1133799

Fayowski, V., & MacMillan, P. D. (2008). An evaluation of the supplemental instruction programme in a first-year calculus course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 39(7), 843–855.

Ford, N., Thackeray, C., Barnes, P., & Hendrickx, K. (2015). Peer learning leaders: Developing employability through facilitating the learning of other students. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 8, 1–23.

Fox, A., Stevenson, L., Connelly, P., Duff, A., & Dunlop, A. (2010). Peer-mentoring undergraduate accounting students: The influence on approaches to learning and academic performance. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(2), 145–156.

Gillies, D., & Mifsud, D. (2016). Policy in transition: The emergence of tackling early school leaving (ESL) as EU policy priority. Journal of Education Policy, 31(6), 819–832.

Ginsburg-Block, M. D., Rohrbeck, C. A., & Fantuzzo, J. W. (2006). A meta-analytic review of social, self-concept, and behavioral outcomes of peer-assisted learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4), 732–749.

Goff, L. (2011). Evaluating the outcomes of a peer-mentoring program for students transitioning to postsecondary education. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 2(2), 1–13.

Griffin, M. M., & Griffin, B. W. (1998). An investigation of the effects of reciprocal peer tutoring on achievement, self-efficacy, and test anxiety. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23(3), 298–311.

Hagedorn, L. S. (2006). How to define retention: New look at an old problem. Transfer and retention of urban community college students. TRUCCS Research Center.

Hall, R., & Jaugietis, Z. (2010). Developing peer mentoring through evaluation. Innovative Higher Education, 36(1), 41–52.

Hycner, R. H. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Human Studies, 8(3), 279–303.

Hycner, R. H. (1999). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. In A. Bryman & R. G. Burgess (Eds.), Qualitative research (Vol. 3, pp. 143–164). Sage.

Ito, M., Gutiérrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., Schor, J., Sefton-Green, J., & Watkins, S. C. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

James, R., Krause, & Jennings. (2010). The first year experience in Australian universities: Findings from a decade of national studies. Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

Johansson, F. (2004). The Medici effect: Breakthrough insights at the intersection of ideas, concepts, and cultures. Harvard Business School Press.

Kung, S., Giles, D., & Hagan, B. (2014). Applying an appreciative Inquiry process to a course evaluation in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 25(1), 29–37.

Lahman, M. P. (1999). To what extent does a peer mentoring program aid in student retention? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Communication Association Conference (85th, Chicago, Illinois, November 4–7).

Lee, J. M., Germain, L. J., Lawrence, E. C., & Marshall, J. H. (2010). It opened my mind, my eyes. It was good. Supporting college students’ navigation of difference in a youth mentoring program. Educational Horizons, 89(1), 33–46.

Lowe, H., & Cook, A. (2003). Mind the gap: Are students prepared for higher education? Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27(1), 53–76.

Maheady, L., & Gard, J. (2010). Classwide peer tutoring: Practice, theory, research, and personal narrative. Intervention in School and Clinic, 46(2), 71–78.

Maheady, L., Mallette, B., & Harper, G. F. (2006). Four classwide peer tutoring models: Similarities, differences, and implications for research and practice. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 22(1), 65–89.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2018). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Sage.

Muldoon, R., & Wijeyewardene, I. (2012). Two approaches to mentoring students into academic practice at university. Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Student Services Association, 39, 21–31.

Ning, H. K., & Downing, K. (2010). The impact of supplemental instruction on learning competence and academic performance. Studies in Higher Education, 35(8), 921–939.

Outhred, T., & Chester, A. (2010). The experience of class tutors in a peer tutoring programme: A novel theoretical framework. Journal of Peer Learning, 3(1), 12–23.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students (Vol. 2): A third decade of research (review). Journal of College Student Development, 47(5), 589–592. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2006.0055.

Peterfreund, A. R., Rath, K. A., Xenos, S. P., & Bayliss, F. (2007). The impact of supplemental instruction on students in STEM courses: Results from San Francisco State University. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 9(4), 487–503.

Piaget., J. (1987). Possibility and necessity. University of Minnesota Press.

Pleschová, G., & McAlpine, L. (2015). Enhancing university teaching and learning through mentoring: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 4(2), 107–125.

Rayle, A. D., & Chung, K.-Y. (2008). Revisiting first-year college students’ mattering: Social support, academic stress, and the mattering experience. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 9(1), 21–37.

Rienties, B., Beausaert, S., Grohnert, T., Niemantsverdriet, S., & Kommers, P. (2012). Understanding academic performance of international students: The role of ethnicity, academic and social integration. Higher Education, 63(6), 685–700.

Robinson, D. R., Schofield, J. W., & Steers-Wentzell, K. L. (2005). Peer and cross-age tutoring in math: Outcomes and their design implications. Educational Psychology Review, 17(4), 327–362.

Roscoe, R. D., & Chi, M. T. H. (2007). Understanding tutor learning: Knowledge-building and knowledge-telling in peer tutors’ explanations and questions. Review of Educational Research, 77(4), 534–574.

Severiens, S., & Wolff, R. (2008). A comparison of ethnic minority and majority students: Social and academic integration, and quality of learning. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3), 253–266.

Smith, D. I. (2009). Changes in transitions: The role of mobility, class and gender. Journal of Education and Work, 22(5), 369–390.

Smith, J., May, S., & Burke, L. (2007). Peer assisted learning: A case study into the value to student mentors and mentees. Practice and Evidence of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 2(2), 80–109.

Solinger, O. N., Hofmans, J., Bal, P. M., & Jansen, P. G. W. (2015). Bouncing back from psychological contract breach: How commitment recovers over time. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 37(4), 494–514.

Sosik, J. J., & Godshalk, V. M. (2000). Leadership styles, mentoring functions received, and job-related stress: A conceptual model and preliminary study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(4), 365–390.

Stigmar, M. (2016). Peer-to-peer teaching in higher education: A critical literature review. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 24(2), 124–136.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (2003). Promoting student retention through classroom practice. In Enhancing student retention: Using international policy and practice. International Conference Sponsored by the European Access Network and the Institute for Access Studies. Staffordshire University.

Tinto, V. (2006). Research and practice of student retention: What next? Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 8(1), 1–19.

Tinto, V. (2010). From theory to action: Exploring the institutional conditions for student retention. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 25). Springer.

Tinto, V. (2012). Enhancing student success: Taking the classroom success seriously. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 3(1), 1–8.

Tinto, V. (2015). Through the eyes of students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 19(3), 254–269.

Tinto, V., & Pusser, B. (2006). Moving from theory to action: Building a model of institutional action for student success. National Postsecondary Education Cooperative. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/npec/pdf/tinto_pusser_report.

Topping, K. (2005). Trends in peer learning. Educational Psychology, 25(6), 631–645.

Topping, K. (2015). Peer tutoring: Old method, new developments/Tutoría entre iguales: Método antiguo, nuevos avances. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 38(1), 1–29.

Topping, K., & Ehly, S. (1998). Peer-assisted learning. Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Topping, K. J., Duran, D., & Van Keer, H. (2016). Using peer tutoring to improve reading skills. Routledge.

Topping, K., Hill, S., McKaig, A., Rogers, C., Rushi, N., & Young, D. (1997). Paired reciprocal peer tutoring in undergraduate economics. Innovations in Education and Training International, 34(2), 96–113.

Torenbeek, M., Jansen, E., & Hofman, A. (2010). The effect of the fit between secondary and university education on first-year student achievement. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 659–675.

Twomey, J. L. (1991). Academic performance and retention in a peer mentor program at a two-year campus of a four-year institution. New Mexico State University.

Van der Meer, J., & Scott, C. (2009). Students’ experiences and perceptions of peer assisted study sessions: Towards ongoing improvement. Australasian Journal of Peer Learning, 2(1), 3–22.

Van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. State University of New York Press.

Vossensteyn, J. L., Kottmann, A., & Jongbloed, B. W. A. (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union.

Watkins, J. M., & Mohr, B. J. (2001). Appreciative inquiry: Change at the speed of imagination. Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Whitney, D. D., & Trosten-Bloom, A. (2010). The power of appreciative inquiry: A practical guide to positive change. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(6), 707–722.

Wu, P. (2013). Bridging the transition process for first-year students in distance construction programs: A case study in Australia. FYHE Conference Committee.

Zepke, N., Leach, L., & Prebble, T. (2006). Being learner centred: One way to improve student retention? Studies in Higher Education, 31(5), 587–600.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Byl, E., Topping, K.J., Struyven, K., Engels, N. (2023). Peer Interaction Types for Social and Academic Integration and Institutional Attachment in First Year Undergraduates. In: Noroozi, O., De Wever, B. (eds) The Power of Peer Learning. Social Interaction in Learning and Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-29410-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-29411-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)