Abstract

Retroperitoneal (RP) masses represent a wide variety of pathologies. They can grow to a substantial size before presenting symptoms that lead to imaging work-up. They are also often detected incidentally due to increased use of cross-sectional imaging. Contrast-enhanced CT is the modality of choice, yet MRI can clarify involvement of muscle, bone, or neural foramina. 18F FDG PET/CT is not routinely indicated, however, for lesions which are inaccessible to percutaneous biopsy it can differentiate between intermediate/high-grade lesions and low grade/benign lesions. This chapter aims to describe the most common indeterminate RP masses and to highlight features which help in the differential diagnosis.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

FormalPara Learning Objectives-

To describe the most common indeterminate retroperitoneal mass lesions and to highlight features which should raise suspicion for retroperitoneal sarcoma

-

To outline safe practice for tissue diagnosis

-

To understand the diagnostic value of imaging modalities in the differential diagnosis

-

To comprehend the diagnostic limits of imaging in differentiating retroperitoneal pathologies

5.1 Introduction

The retroperitoneum can host a broad spectrum of pathologies and masses can grow to a substantial size before presenting symptoms and signs such as abdominal swelling, early satiety, hernias, testicular swelling, nerve irritation, or lower limb swelling. Due to increased use of cross-sectional imaging, retroperitoneal (RP) masses may also be incidental findings. Although soft-tissue sarcomas (STS) are rare, in the RP they can account for up to a third of tumors and must therefore be considered as a differential diagnosis [1]. In 291 patients with indeterminate RP mass lesions, 79.4% were mesenchymal (55.8% were adipocytic (liposarcoma, angiomyolipoma, myelolipoma), and 36.8% non-adipocytic (schwannoma, leiomyosarcoma, desmoid, other sarcomas)); 53.3% were non-mesenchymal (metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, germ cell, other) [2]. STS patients treated at high volume centers have significantly better survival and functional outcomes and therefore any suspicion for STS should trigger early referral [3].

Contrast-enhanced CT is the modality of choice, yet MRI can clarify involvement of muscle, bone, or neural foramina. 18F FDG PET/CT is not routinely indicated, however, for lesions which are inaccessible to percutaneous biopsy it can differentiate between intermediate/high-grade lesions and low grade/benign lesions, but critically it is unable to differentiate between low grade and benign lesions [4].

This chapter aims to describe the most common indeterminate RP mass lesions and to highlight features which should raise suspicion for RP sarcoma.

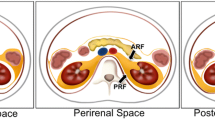

5.2 Retroperitoneal Space

The RP space is divided into four anatomically separate compartments [5]: the posterior pararenal space is encompassed by the posterior parietal peritoneum. The anterior pararenal space extends to the transversalis fascia [5]. The perirenal space is encapsulated by the perirenal fascia. The anterior pararenal space contains visceral organs that mainly originate from the dorsal mesentery, i.e., the pancreas and the descending and ascending parts of the colon. The perinephric space is bounded anteriorly by Gerota’s fascia and posteriorly by Zuckerkandl’s fascia [5]. It contains the kidneys and adrenal glands. The perinephric space is home to bridging septa and a network of lymphatic vessels, which may facilitate the spread of disease processes to or from adjacent spaces. The perinephric space is limited caudally by the merging of Gerota’s and Zuckerkandl’s fascias and therefore does not continue into the pelvic region [5]. The posterior pararenal space is bound by the transversalis fascia on its posterior face. Anatomic communication between the posterior pararenal space and the structures of the flank wall may be established. A fourth space surrounds the large vessels, the aorta, and the inferior vena cava. This space has a lateral boundary with the perirenal spaces and ureters and extends cranially into the posterior mediastinum [5]. Some diseases, for example, RP fibrosis, are largely limited to this space. Depending on the definition, some sources refer to a fifth space, which includes the muscular structures with psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles.

Key Point

Recognizing the retroperitoneal origin of masses is crucial to narrow down the list of differential diagnoses.

5.3 Tissue Diagnosis

Apart from RP liposarcoma and renal angiomyolipoma, accurate characterization of indeterminate RP masses on imaging alone is challenging [2]. Therefore, a tissue diagnosis is imperative, and image-guided percutaneous coaxial core needle biopsy is safe and preferred. If a diagnosis of STS is suspected radiologically, the biopsy should preferentially be performed at a specialist sarcoma center to expedite final diagnosis through expert pathology review. Multiple needle cores (ideally 4–5 at 16G) should be obtained to allow for histologic and molecular subtyping. Although percutaneous core biopsy is accurate for diagnosis, under-grading of pathologies such as sarcoma is recognized due to sampling error [6, 7]. Use of functional imaging techniques such as 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT and contemporary robotic-assisted CT-guided biopsy techniques have immense potential to improve sampling of the most deterministic tumor elements [8]. The RP route is preferred and the transperitoneal approach only utilized following discussion at multidisciplinary tumor boards when the tumor is inaccessible via the retroperitoneum. Risk of needle track seeding when the RP route is respected is minimal and core needle biopsy does not negatively influence outcome [9].

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology rarely yields sufficient diagnostic information and is not recommended. An open or laparoscopic surgical incision/excision biopsy of an RP mass is discouraged as it exposes the peritoneal cavity to contamination and distorts planes of dissection if subsequent completion surgery is necessary [10]. Incision or excision biopsy of an indeterminate RP mass should only be performed after specialist sarcoma multidisciplinary review.

Key Point

Percutaneous core needle biopsy of indeterminate retroperitoneal masses is safe and does not adversely affect outcomes.

5.4 Adipocytic Tumors

As a substantial proportion of mesenchymal RP masses are adipocytic (55.8%), it is useful to establish early whether there is abnormal macroscopic fat associated with an indeterminate RP mass [2, 11]. This should include careful interrogation of whether the fat containing mass originates from the kidney or adrenal leading to a more reassuring diagnosis of benign renal angiomyolipoma (AML) or adrenal myelolipoma (ML), respectively. The presence of renal cortical defects and prominent vessels strengthens the diagnosis of the AML [12] and adrenal ML tend to be more well defined than RP liposarcoma. If the adipocytic mass is not arising from the solid viscera, a diagnosis of RP liposarcoma should be considered and referral to a soft-tissue sarcoma unit made.

Expansile macroscopic fat external to the solid abdominal viscera is highly suspicious for well-differentiated liposarcoma and the presence of solid enhancing elements suggests dedifferentiation (Fig. 5.1). In adults over 55, liposarcoma is the commonest RP sarcoma, accounting for up to 70% of RP sarcomas [13]. Well-differentiated liposarcoma does not metastasize but can dedifferentiate and develop high-grade non-adipocytic elements with potential to metastasize. Well and dedifferentiated liposarcoma characteristically harbor supernumerary ring and/or giant chromosomes in relation to amplification of several genes in the 12q13–15 region. These include MDM2, CDK4, and HMGA2, which can be of diagnostic use [14]. Calcifications may be present and can indicate dedifferentiation or may reflect sclerosing or inflammatory variants of WDL [15]. The presence of fat is not always immediately apparent, and careful evaluation is crucial. Failure to recognize the presence of abnormal fat is the commonest reason for misdiagnosis and mismanagement. If the well-differentiated component is not recognized, incomplete resection may follow which deprives the patient of potentially curative surgery. Furthermore, several foci of dedifferentiation can be misinterpreted as multifocal disease contraindicating surgery or leading to piecemeal resection; however, this usually represents separate foci of dedifferentiation within a single contiguous liposarcoma with well-differentiated elements between the solid masses. This is treated as unifocal disease [10].

Liposarcoma. Well-differentiated liposarcoma typically appears as a relatively bland fat density mass with minimal internal complexity, displacing adjacent structures (a). In contrast, dedifferentiated liposarcoma in another patient appears as a solid mass (b). The diagnosis of the solid mass seen in image b is challenging until the well-differentiated component extending into the left inguinal canal is identified (c)

Absence of macroscopic fat in an RP mass does not exclude a diagnosis of RP liposarcoma. This may represent disease that has dedifferentiated throughout or a sclerosing subtype. Anatomic constraints within the retroperitoneum limit the ability to achieve wide resection margins. As a consequence, local recurrence of RPS is more frequent than for extremity sarcoma and represents the leading cause of death [16]. Tumor grade and macroscopic complete resection are the two most important and consistent independent factors that predict oncological outcome. Other factors include patient age, tumor subtype, microscopic resection margins, tumor size, primary or recurrent disease, multifocality, multimodality treatment and centralized multidisciplinary management in a specialist sarcoma center [14]. In liposarcomas, local recurrence dictates outcome as the main mode of disease recurrence (70% 5-year local recurrence), while systemic metastases are rare (10–15% 5-year distant disease recurrence) [17]. Although rare in the retroperitoneum, benign fat-containing extragonadal dermoids, hibernomas, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and lipomas can also mimic RP liposarcomas. Therefore, biopsy must always be performed.

Key Point

Absence of macroscopic fat in a retroperitoneal mass does not exclude a diagnosis of liposarcoma. This may represent disease that has dedifferentiated throughout.

5.5 Other Soft-Tissue Sarcomas

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the second most common RP sarcoma accounting for up to 15% of all RPS. The exception is in younger adults where LMS can supersede liposarcoma. LMS usually arise from the IVC below the level of the hepatic veins (Fig. 5.2), but they do also arise from smaller vessels such as the renal veins or less commonly the gonadal veins [18]. LMS commonly have an exophytic component, which can make differentiation from extrinsic compression challenging. Unlike liposarcomas where local recurrence dictates outcome, LMS are much less likely to recur locally but systemic metastases, usually to the lungs, are much more common [14]. After LMS, the remaining 5% of RPS are composed of much rarer sarcoma subtypes. The commonest of these are described below.

Synovial sarcoma is the fifth commonest sarcoma overall, typically affecting young adults (15–40 years). Despite the name, the tissue of origin is not synovium but undifferentiated mesenchyme; it simply most resembles adult synovium microscopically. Synovial sarcoma is a high-grade tumor with 5-year survival rates of less than 50% [19, 20]. Imaging findings are generally those of a non-specific heterogeneous mass; however, many display smooth well-defined margins with cystic contents, leading to an erroneous diagnosis of a benign ganglion or myxoma [21] (Fig. 5.3). 30% contain calcification [21]. Changes compatible with hemorrhage are seen in 40% of cases and fluid-fluid levels are seen in around 20% of lesions [22]. As with other STSs the lung is the main site of metastasis, which occurs in over 50% of patients and 25% of patients present with metastatic disease. Synovial sarcoma is one of the few sarcomas which commonly spread to regional lymph nodes, occurring in up to 20% of cases [20, 21].

Synovial sarcoma. Large left-sided retroperitoneal mass in a 30-year-old lady was biopsy-proven synovial sarcoma. Cystic looking change is common (A) which together with well-defined margins can lead to a misdiagnosis of benign neurogenic tumor. Therefore, biopsy of indeterminate retroperitoneal masses is mandatory for accurate diagnosis

Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcomas (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytomas) are high-grade sarcomas which are thought to represent a heterogeneous group of poorly differentiated tumors which may be the poorly differentiated endpoints of many mesenchymal lineages. As the morphological pattern is shared by many poorly differentiated neoplasms, it is important to exclude pleomorphic variants of more common tumor types (i.e., sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma). Most UPSs in the retroperitoneum are now considered to represent dedifferentiated liposarcoma [23, 24]. In view of this, a histological diagnosis of RP poorly differentiated sarcoma warrants close correlation with clinical history to see if there is a history of well-differentiated liposarcoma. Immunohistochemistry for MDM2 and CDK4 gene products, and cytogenetic analysis to assess MDM2 gene amplification status may also be beneficial. This has prognostic implications as dedifferentiated liposarcoma tends to be less aggressive than other pleomorphic sarcomas [25].

The finding of a large, well-circumscribed solid, vascular tumor, particularly with prominent feeding vessels should introduce the possibility of solitary fibrous tumor (Fig. 5.4). The presence of fat may suggest lipomatous hemangiopericytoma, a subtype of SFT [26].

Key Point

Liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma are the commonest soft-tissue sarcomas occurring in the retroperitoneum.

5.6 Neurogenic Tumors

Neurogenic tumors make up 10%–20% of primary RP masses [27] and manifest at a younger age and are more frequently benign. They develop from the nerve sheath, ganglionic or paraganglionic cells, and are commonly observed along the sympathetic nerve system, in the adrenal medulla, or in the organs of Zuckerkandl [28].

Schwannomas represent benign masses that arises from the perineural sheath and account for 6% of RP neoplasms [27]. They usually present without symptoms and occur around the second to fifth decade. It is an encapsulated tumor along the nerve. Degenerative changes can be present (i.e., ancient schwannomas), as well as hemorrhage, cystic changes, or calcification. Schwannomas are often found in the paravertebral region. They demonstrate variable homogeneous or heterogeneous contrast enhancement [27]. Cystic areas appear hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences whereas cellular areas appear hypointense on T1- and T2-weighted images [29].

Malignant nerve sheath tumors include malignant schwannoma, neurogenic sarcoma, and neurofibrosarcoma. Half develop spontaneously and half originate from neurofibroma, ganglioneuroma, or prior radiation [28]. Ongoing enlargement, irregular boundaries, pain, heterogeneous appearance, and infiltration in surrounding structures raise suspicion for malignancy, in particular for neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) patients [27].

Neurofibromas are a benign nerve sheath tumors that are either unifocal (90%) or part of NF1. About a third of single and all multifocal tumors are associated with NF1 [27]. They are unencapsulated solid tumors consisting of nerve sheath and collagen bundles on pathology. Variable myxoid degeneration exists and cystic degeneration is infrequent. On imaging, it presents as a well-circumscribed, homogeneous, low attenuating lesion (about 25 HU), resulting from lipid-rich components. On T2-weighted sequences, the periphery has higher signal owing to myxoid degeneration [27]. Malignant transformation is more frequent with neurofibroma than schwannoma, particularly in NF1 patients [27]. An example of an RP neurofibroma is shown (Fig. 5.5).

Neurofibroma. Neurofibromas typically present as hypodense masses with no or minimal contrast enhancement (a, c, d). The patient had originally been examined for metastatic prostate cancer; there was no PSMA expression of the mass (b). Neurofibromas are not encapsulated and tend to be less well defined, in contrast to other neurogenic tumors like schwannomas. Local infiltration of adjacent structures makes resections difficult

Ganglioneuroma is a rare benign tumor that arises from the sympathetic ganglia [27]. Most commonly asymptomatic, it can sometimes produce hormones such as catecholamines, vasoactive peptides, or androgenic hormones. The most common sites are retroperitoneum and mediastinum. In the retroperitoneum, the tumor is frequently located along the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia. At imaging, it presents as a well-circumscribed, sometimes lobulated, low attenuating mass [27]. Necrosis and hemorrhage are rare, and there is variable contrast enhancement. On T2-weighted sequences, ganglioneuromas demonstrate variable signal, which depends on the myxoid, cellular, and collagen composition.

Paragangliomas are tumors in an extra-adrenal location that arise from chromaffin cells, where tumors that arise from cells of the adrenal medulla are referred to as pheochromocytomas [27]. About 40% of paragangliomas secrete high levels of catecholamines, leading to symptoms such as headache, palpitations, excessive sweating, and elevated urinary metabolites. Paragangliomas can be associated with NF1, multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome, and von Hippel–Lindau syndrome [27]. The most frequent retroperitoneal location is the organs of Zuckerkandl. On imaging, they typically present as large well-defined lobular tumors and may contain areas of hemorrhage and necrosis; hence, variable signal is observed on T2-weighted sequences. Its hypervascular nature frequently results in intense contrast enhancement [27]. The tumor frequently has a heterogeneous appearance due to hemorrhages. Radionuclide imaging performed with m-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) or 18F-DOPA shows high uptake in paragangliomas [30]. Paragangliomas are more aggressive and metastasize in up to 50% of cases. An example of an RP extra-adrenal paraganglioma with strong DOPA decarboxylase activity is shown (Fig. 5.6).

Key Point

Retroperitoneal neurogenic tumors are commonly observed along the sympathetic nerve system, in the adrenal medulla, or in the organs of Zuckerkandl.

5.7 Miscellaneous

Among the most common RP masses are lymphomas. These are highly prevalent and less frequently indeterminate, yet tissue diagnosis remains a cornerstone of management. The hematological malignancies may also present with RP manifestations of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease, extraosseous myelomas or extramedullary leukemias (i.e., extramedullary disease manifestations) [27]. This disease group typically manifests as solid masses in the form of lymphadenopathy yet may also contain liquid intralesional components as a result of necrosis in highly aggressive hematological malignancies. Benign tumors include lymphangiomas, benign germ cell tumors, or sex cord tumors [27]. For the latter two, serological tumor markers may aid in narrowing the list of differentials. Other rare nonneoplastic masses may include pseudotumoral lipomatosis, RP fibrosis, extramedullary hematopoiesis, IgG4-related disease, or Erdheim-Chester disease [27]. The latter two can have a characteristic imaging appearance with soft-tissue bands surrounding the kidneys in the perinephric space. Finally, the RP space may also represent a location for metastatic spread of disease. Most notably, these include lymph node metastasis from a large group of abdominal and pelvic malignancies. The most common primary, non-lymphoid malignancies to metastasize to the RP space outside of lymph nodes are melanomas and urogenital malignancies.

Key Point

The large variety of rare retroperitoneal masses and overlap of imaging appearance highlights the limitations of non-invasive diagnostic tests and underlines the need for minimally invasive tissue diagnosis.

5.8 Concluding Remarks

The retroperitoneum can host a broad spectrum of pathologies, and the radiologist plays a pivotal role in providing a differential diagnosis and guiding management. Although STS are rare, in the retroperitoneum they can account for up to a third of cases in some series. The commonest RPS, liposarcoma and LMS, have characteristic imaging appearances; however, there are many other STS that can occur in the RP. It is unreasonable and unnecessary to expect that all radiologists should recognize these rarer subtypes. Instead, referral to specialist sarcoma units is recommended where the diagnosis of an RP mass remains indeterminate.

Take Home Messages

-

Recognizing the retroperitoneal origin of masses is crucial to narrow down the list of differential diagnoses.

-

Percutaneous core needle biopsy of indeterminate RP masses is safe and does not adversely affect outcomes.

-

Liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma are the commonest soft-tissue sarcomas occurring in the retroperitoneum. Absence of macroscopic fat in a retroperitoneal mass does not exclude a diagnosis of liposarcoma. This may represent disease that has dedifferentiated throughout.

-

Retroperitoneal neurogenic tumors are commonly observed along the sympathetic nerve system, in the adrenal medulla, or in the organs of Zuckerkandl.

-

The large variety of rare RP masses and overlap of imaging appearance highlights the limitations of non-invasive diagnostic tests and underlines the need for minimally invasive tissue diagnosis.

References

Van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC. Soft tissue tumours of the retroperitoneum. Sarcoma. 2000;4(1-2):17–26. https://doi.org/10.1155/S1357714X00000049.

Morosi C, Stacchiotti S, Marchiano A, Bianchi A, Radaelli S, Sanfilippo R, et al. Correlation between radiological assessment and histopathological diagnosis in retroperitoneal tumors: analysis of 291 consecutive patients at a tertiary reference sarcoma center. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(12):1662–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2014.10.005.

Gutierrez JC, Perez EA, Moffat FL, Livingstone AS, Franceschi D, Koniaris LG. Should soft tissue sarcomas be treated at high-volume centers? An analysis of 4205 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245(6):952–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000250438.04393.a8.

Ioannidis JP, Lau J. 18F-FDG PET for the diagnosis and grading of soft-tissue sarcoma: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Med. 2003;44(5):717–24.

Tirkes T, Sandrasegaran K, Patel AA, Hollar MA, Tejada JG, Tann M, et al. Peritoneal and retroperitoneal anatomy and its relevance for cross-sectional imaging. Radiographics. 2012;32(2):437–51. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.322115032.

Strauss DC, Qureshi YA, Hayes AJ, Thway K, Fisher C, Thomas JM. The role of core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of suspected soft tissue tumours. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(5):523–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.21600.

Schneider N, Strauss DC, Smith MJ, Miah AB, Zaidi S, Benson C, et al. The adequacy of core biopsy in the assessment of smooth muscle neoplasms of soft tissues: implications for treatment and prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(7):923–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000867.

Johnston EW, Basso J, Winfield J, McCall J, Khan N, Messiou C, et al. Starting CT-guided robotic interventional oncology at a UK centre. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1134):20220217. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20220217.

Wilkinson MJ, Martin JL, Khan AA, Hayes AJ, Thomas JM, Strauss DC. Percutaneous core needle biopsy in retroperitoneal sarcomas does not influence local recurrence or overall survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(3):853–8. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4059-x.

Bonvalot S, Raut CP, Pollock RE, Rutkowski P, Strauss DC, Hayes AJ, et al. Technical considerations in surgery for retroperitoneal sarcomas: position paper from E-Surge, a master class in sarcoma surgery, and EORTC-STBSG. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2981–91. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2342-2.

Messiou C, Moskovic E, Vanel D, Morosi C, Benchimol R, Strauss D, et al. Primary retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: Imaging appearances, pitfalls and diagnostic algorithm. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(7):1191–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2016.10.032.

Katabathina VS, Vikram R, Nagar AM, Tamboli P, Menias CO, Prasad SR. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the kidney in adults: imaging spectrum with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30(6):1525–40. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.306105517.

Strauss DC, Hayes AJ, Thway K, Moskovic EC, Fisher C, Thomas JM. Surgical management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97(5):698–706. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6994.

Miah AB, Hannay J, Benson C, Thway K, Messiou C, Hayes AJ, et al. Optimal management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma: an update. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(5):565–79. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737140.2014.883279.

Craig WD, Fanburg-Smith JC, Henry LR, Guerrero R, Barton JH. Fat-containing lesions of the retroperitoneum: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29(1):261–90. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.291085203.

Swallow CJ, Strauss DC, Bonvalot S, Rutkowski P, Desai A, Gladdy RA, et al. Management of Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma (RPS) in the Adult: An Updated Consensus Approach from the Transatlantic Australasian RPS Working Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-09654-z.

Singer S, Antonescu CR, Riedel E, Brennan MF. Histologic subtype and margin of resection predict pattern of recurrence and survival for retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Ann Surg. 2003;238(3):358–70; discussion 70-1. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000086542.11899.38.

Ganeshalingam S, Rajeswaran G, Jones RL, Thway K, Moskovic E. Leiomyosarcomas of the inferior vena cava: diagnostic features on cross-sectional imaging. Clin Radiol. 2011;66(1):50–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2010.08.004.

Van Slyke MA, Moser RP Jr, Madewell JE. MR imaging of periarticular soft-tissue lesions. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 1995;3(4):651–67.

Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Malignant tumors of uncertain type. Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. Mosby; 2001.

Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD, Synovial tumors. Imaging of soft tissue tumors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Jones BC, Sundaram M, Kransdorf MJ. Synovial sarcoma: MR imaging findings in 34 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(4):827–30. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.161.4.8396848.

Coindre JM, Mariani O, Chibon F, Mairal A, De Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, Favre-Guillevin E, et al. Most malignant fibrous histiocytomas developed in the retroperitoneum are dedifferentiated liposarcomas: a review of 25 cases initially diagnosed as malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2003;16(3):256–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000056983.78547.77.

Binh MB, Guillou L, Hostein I, Chateau MC, Collin F, Aurias A, et al. Dedifferentiated liposarcomas with divergent myosarcomatous differentiation developed in the internal trunk: a study of 27 cases and comparison to conventional dedifferentiated liposarcomas and leiomyosarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(10):1557–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31804b4109.

McCormick D, Mentzel T, Beham A, Fletcher CD, Dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 32 cases suggesting a better prognostic subgroup among pleomorphic sarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(12):1213–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199412000-00004.

Wignall OJ, Moskovic EC, Thway K, Thomas JM. Solitary fibrous tumors of the soft tissues: review of the imaging and clinical features with histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(1):W55–62. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.09.3379.

Rajiah P, Sinha R, Cuevas C, Dubinsky TJ, Bush WH Jr, Kolokythas O. Imaging of uncommon retroperitoneal masses. Radiographics. 2011;31(4):949–76. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.314095132.

Improta L, Tzanis D, Bouhadiba T, Abdelhafidh K, Bonvalot S. Overview of primary adult retroperitoneal tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(9):1573–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.04.054.

Czeyda-Pommersheim F, Menias C, Boustani A, Revzin M. Diagnostic approach to primary retroperitoneal pathologies: what the radiologist needs to know. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46(3):1062–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-020-02752-8.

Kunz WG, Auernhammer CJ, Nölting S, Pfluger T, Ricke J, Cyran CC. Phäochromozytom und Paragangliom. Der Radiologe. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00117-019-0569-7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Messiou, C., Kunz, W.G. (2023). Indeterminate Retroperitoneal Masses. In: Hodler, J., Kubik-Huch, R.A., Roos, J.E., von Schulthess, G.K. (eds) Diseases of the Abdomen and Pelvis 2023-2026. IDKD Springer Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27355-1_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27355-1_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-27354-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-27355-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)