Abstract

Uncertainty surrounding global change impacts on future forest conditions has motivated the development of silviculture strategies and frameworks focused on enhancing potential adaptation to changing climate and disturbance regimes. This includes applying current silvicultural practices, such as thinning and mixed-species and multicohort systems, and novel experimental approaches, including the deployment of future-adapted species and genotypes, to make forests more resilient to future changes. In this chapter, we summarize the general paradigms and approaches associated with adaptation silviculture along a gradient of strategies ranging from resistance to transition. We describe how these concepts have been operationalized and present potential landscape-scale frameworks for allocating different adaptation intensities as part of functionally complex networks in the face of climate change.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Silvicultural systems have long been intended to represent a working hypothesis adapted over time to address unanticipated changes in treatment outcomes or the impacts of exogenous factors, including natural disturbances and changing market conditions and objectives (Smith, 1962). Nevertheless, silvicultural approaches have assumed a general level of predictability in outcomes, with risks avoided or minimized through a top-down control of ecosystem attributes and properties, such as dominant tree species and genotypes, stand densities, soil fertility, and age structures (Palik et al., 2020; Puettmann et al., 2009). The increasing departure of environmental conditions from those under which many of these silvicultural practices and systems were developed has led to an explicit need for adaptive silvicultural approaches that account for future uncertainty and novelty in forests around the globe (Millar et al., 2007; Puettmann, 2011).

This chapter summarizes the general frameworks and approaches for developing silvicultural strategies that confer adaptation to forest ecosystems in the face of novel dynamics, including changes in disturbance and climate regimes and the proliferation of nonnative species. Experience with adaptation silviculture is in its infancy compared with traditional applications. Therefore, our focus is primarily on early outcomes of operational-scale experiments and demonstrations and landscape- and regional-scale simulations of long-term dynamics under adaptive silvicultural approaches. Our goal is to introduce new conceptual frameworks for adaptive silviculture as context for the chapters in Sect. 13.5 of this book. Although the discussion is focused on temperate and boreal ecosystems in North America and Europe, the conceptual frameworks are appropriate for many different forest ecosystems around the globe. Subsequent chapters provide more detail on specific facets of managing for adaptation in boreal ecosystems, including the role of plantation silviculture and tree improvement (Chap. 14), management for mixed species and structurally complex conditions (Chap. 15), and large-scale experiments inspired by natural disturbance emulation (Chap. 16).

1.1 Silvicultural Challenges in the Face of Climate Change

Historically, silvicultural approaches and practices have reflected changing economic and social conditions (Puettmann et al., 2009). In contrast, ecological conditions have been sufficiently constant that foresters did not see the need to alter silvicultural approaches to accommodate changing ecological conditions. As a result, climate change enhances existing challenges and adds novel complexities to silviculture, given the limited experience of managing forests in a rapidly changing environment (Table 13.1). From a forest management perspective, the overarching challenge for addressing global change is to deal with trends and the uncertainty of future climate and disturbance regimes and the associated ecosystem dynamics and societal demands (Puettmann, 2011). In this context, selected aspects of climate change are being predicted rather consistently, e.g., the general increase in temperature and growing season length in boreal forests. Other aspects of climate change provide additional challenges of high uncertainty, including the magnitude of temperature increases among regions. Even more challenging are predictions of, for example, contrasting and variable precipitation patterns (Alotaibi et al., 2018).

The degree of certainty of future conditions influences the ability to prepare and minimize negative impacts (Meyers & Bull, 2002; Puettmann & Messier, 2020). Silvicultural practices directly aimed at accommodating temperature increases, for example, can be implemented relatively easily (Chmura et al., 2011; Hemery, 2008; Park et al., 2014), for instance favoring species or genotypes adapted to the projected temperatures. In contrast, foresters have less confidence when selecting specific silvicultural practices to accommodate novel disturbance regimes or an altered seasonality of precipitation patterns. In such cases, multiple practices may be promising, but the specific selections can only be viewed as bet hedging (sensu Meyers & Bull, 2002), which is based conceptually on the insurance hypothesis (Yachi & Loreau, 1999).

Another challenge arises through a temporal-scale mismatch. Forests are slow to respond to many silvicultural manipulations, e.g., conversion from single to multiple canopy layers will likely take several decades. Thus, managing for changing conditions requires a certain lead time (Biggs et al., 2009), an unlikely scenario with the immediacy of future climate and other global changes. At the same time, managing for future climate conditions can result in short-term incompatibilities or mismatches that may generate near-term undesirable outcomes in regard to ecosystem productivity and structure (Wilhelmi et al., 2017) and lead to failures (e.g., regeneration) that may be viewed as too risky in reforestation activities.

Natural disturbances are crucial elements to consider in any silvicultural planning because of their substantial economic and ecological implications and potentially significant impact on forest productivity, carbon sequestration, and timber supplies (Flint et al., 2009; Kurz et al., 2008; Seidl et al., 2014). Climate change predictions indicate that the effects on boreal ecosystems will be profound, and natural disturbance cycles (e.g., fire, insect outbreaks, and windthrow) will generally increase in frequency and severity (Seidl et al., 2017). These projections introduce a potentially massive new challenge to silvicultural planning. For example, the first evidence of the northward movement of spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) outbreaks has recently been reported combined with an increase in the frequency and level of damage during the last century; these findings indicated climate change to be the main cause of the altered spatiotemporal patterns of spruce budworm outbreaks in eastern Canadian boreal forests (Navarro et al., 2018). Climate change is expected to expand the range of natural disturbance variability in forest ecosystems beyond those under which past strategies, including ecosystem-based management (Christensen et al., 1996), have been developed. Thus, a better understanding of how forest landscapes will respond to alterations in natural disturbances is needed to mitigate negative effects and adapt boreal forest management strategies to projections of climate change.

Vulnerability assessments of ecosystem attributes that quantify sensitivity to projected climate changes and the adaptive capacity to respond to these and disturbance impacts (Mumby et al., 2014) have become a common strategy for addressing uncertainty. These assessments are also used to guide where adaptive silviculture may have the greatest benefit for meeting long-term management goals (Gauthier et al., 2014). In practical terms, the vulnerability of a forest type is based on the degree of climate and disturbance impacts expected in a region and the ability of the forest to respond to those impacts without a major change in forest conditions in terms of structure and function (Janowiak et al., 2014). Just as with actual climate change, vulnerability can vary regionally stemming from differences in biophysical settings within the stand because of variable tree-level conditions (e.g., resource availability and tree species, size, and age) and temporally owing to ontogenetic shifts in tree- and stand-level conditions (Daly et al., 2010; Frey et al., 2016; Nitschke & Innes, 2008). Therefore, adaptation strategies must be tailored to regional and within-stand vulnerabilities and be flexible to account for changing vulnerabilities over time. For example, adaptation strategies applied to ecosystems having a low vulnerability may resemble current management practices and be designed to maintain current forest conditions and refugia (Thorne et al., 2020). In contrast, strategies applied to highly vulnerable ecosystems, such as those in boreal regions where natural migration is expected to be outpaced by climate change and disturbance impacts (Aubin et al., 2018), may need to employ deliberate actions to increase adaptive capacity. In the latter case, silvicultural strategies may look very different from current practices. The following section outlines general adaptation strategies broadly recognized for addressing climate change. However, their appropriateness for any given situation must be informed by regional- and site-level vulnerability assessments and overall management goals. The remaining sections present outcomes of adaptation approaches specific to temperate and boreal forests.

2 General Adaptation Strategies

Generally, active adaptation practices are categorized into resistance, resilience, and transition (also referred to as response) strategies (Millar et al., 2007; Table 13.2; Fig. 13.1). Note that passive adaptation, while included in Table 13.2, is not discussed further in this chapter, given our focus on active management strategies. Nevertheless, passive approaches, including reserve designation and protection, remain important strategies in the portfolio of options for addressing climate change impacts. Although presented as discrete categories, adaptation strategies fall along a continuum, such that implementation of an adaptation approach may involve elements of two or three categories (Nagel et al., 2017). Moreover, aspects of the tactics and outcomes associated with adaptation strategies are often conceptualized within a complex adaptive-systems framework (Puettmann & Messier, 2020; Puettmann et al., 2009), with structural and functional outcomes and associated multiscale feedbacks created by resistance, resilience, and transition strategies serving to confer ecosystem resilience (Messier et al., 2019). Thus, reliance on multiple adaptation strategies that bridge or reflect more than one category within and across stands is emphasized to generate cross-scale functional linkages and dynamics that allow for rapid recovery and reassembly following disturbances or extreme climate events (Messier et al., 2019).

Gradient of adaptation strategies in a northern hardwood forest in New Hampshire, United States (center column panels) and red pine forests in northern Minnesota, United States (right-hand column panels) ranging from a passive, b resistance, c resilience, to d transition. Left-hand column panels represent kriged surfaces associated with tree (≥10 cm DBH) locations in a 1 ha portion of treatment units in the northern hardwood forests. The passive strategy represents a no-action approach. Resistance strategies represent single-tree selection focused on maintaining low-risk individuals in northern hardwood forests (cf. Nolet et al., 2014) and thinning treatments in red pine forests to increase drought and pest resistance (D’Amato et al., 2013). For both examples, the resilience strategy comprises a single-tree and group selection with patch reserves—similar to variable-density thinning, cf. Donoso et al. (2020)—to increase spatial and compositional complexity (harvest gaps were planted in the red pine forests with future-adapted species found in the present ecosystem). The transition strategy represents continuous cover (northern hardwoods) or expanding gap (red pine) irregular shelterwoods with the planting of future-adapted species in harvest gaps (northern hardwood) or across the entire stand (red pine). Note that the photos in the bottom row are focused on the harvest gap portion or irregular shelterwoods. Photo credits Anthony W. D’Amato. Kriged surfaces created by Jess Wikle.

Resistance strategies focus on adaptation tactics designed to maintain the currently existing forest conditions on a site (Millar et al., 2007) and can be viewed as an expansion of silvicultural practices typically used to maintain and increase tree vigor and limit disturbance impacts (Chmura et al., 2011). A litmus test for a resistance strategy asks whether the forest is still maintaining development trends in structure and composition within observed ranges of variation after exposure to a given stressor relative to areas not experiencing these treatments. Many of these tactics focus therefore on reducing the impacts of stressors, e.g., extreme precipitation events, drought, and disturbance agents, including fire, insects, and diseases, by manipulating tree- and stand-level structure and composition to reduce levels of risk (Swanston et al., 2016).

For example, treatments that increase the abundance of hardwood species in conifer-dominated boreal systems may be categorized as resistance approaches given that they decrease the risk and severity of wildfires (Johnstone et al., 2011) and reduce stand vulnerability to insect outbreaks, such as from spruce budworm, that target conifer components (Campbell et al., 2008). More generally, the application of thinning treatments to increase the available resources for residual trees and thus minimize drought and forest health impacts (Bottero et al., 2017; D'Amato et al. 2013) or fuel reduction treatments to reduce fire severity (Butler et al., 2013) represent resistance strategies broadly applicable to many forest systems. Regardless of the tactics employed, resistance strategies are generally viewed as limited to being near-term solutions but also represent low-risk approaches that are easily understood and implemented by foresters. Thus, they may be suitable for a stand close to the planned rotation age (Puettmann, 2011). Relying solely on resistance strategies is more problematic in the long term given the increasing difficulty and costs expected in maintaining current conditions as global change progresses (Elkin et al., 2015), particularly in boreal regions where the climate is and will be changing rapidly (Price et al., 2013).

As with resistance strategies, resilience strategies largely emphasize maintaining the characteristics of current forest systems; however, the latter differs somewhat by maintaining and enhancing ecosystem properties that support recovery. Therefore, these strategies allow for larger temporary deviations and thus a broader range of compositional and structural outcomes, often bounded by the range of natural variation for the ecosystem (Landres et al., 1999). A litmus test for a resilience strategy is to ask whether the forest conditions return to the ecosystem's existing range of conditions (or historical ranges) after stand response to a treatment and exposure to a given stressor. In contrast to resistance strategies, which try to minimize deviation from current or historic conditions and processes, resilience strategies aim to increase an ecosystem’s ability to recover from disturbances or climate extremes in an attempt to return to pre-perturbation levels of different processes (e.g., aboveground productivity) and structural and compositional conditions (Gunderson, 2000).

Ecosystem attributes and conditions identified as conferring resilience include vegetation and physical structures surviving disturbance (i.e., biological legacies or ecological memory; Johnstone et al., 2016), as well as mixed-species forest conditions in which there is a high degree of functional redundancy among constituent species (Bergeron et al., 1995; Biggs et al., 2020; Messier et al., 2019). Thus, most resilience strategies focus on creating two general stand conditions: mixed species and a heterogeneous structure. In the case of mixed-species conditions, resilience is conferred by including species having a range of functional responses, including different recovery mechanisms following climate extremes (e.g., drought tolerance; Ruehr et al., 2019) and reproductive strategies following disturbance events (e.g., sprouting or seed banking; Rowe, 1983). Approaches that encourage heterogeneous, multicohort structures can reduce vulnerabilities given that climate and disturbance impacts vary with tree size and age (Bergeron et al., 1995; Olson et al., 2018), and the presence of younger age classes provides a mechanism for the rapid replacement of overstory tree mortality via ingrowth (O'Hara and Ramage, 2013). Many of these approaches often build from and resemble ecological silviculture strategies developed to emulate outcomes of natural disturbance regimes for a given forest type (D’Amato & Palik, 2021).

Transition strategies represent the largest deviation from traditional silvicultural frameworks and are applied under the assumption that future climate conditions and prevailing disturbance regimes will become less suitable or even unsuitable for current species and existing forest structural conditions, such as the often high stocking levels used for timber management in many forest types (Rissman et al., 2018). A litmus test for a transition strategy asks whether the expected development of forest characteristics in response to the treatment will eventually fall outside the range of natural variation and accommodate novel conditions. These strategies focus therefore on transitioning forests to species and structural conditions that are predicted to be able to provide desired ecosystem services under future climate and disturbances (Millar et al., 2007). In many cases, transition strategies include the deliberate introduction of future-adapted genotypes or species (e.g., Muller et al., 2019), sometimes through assisted migration, thereby increasing the representation of species and functional attributes likely to be favored under future disturbance and climate regimes (e.g., Etterson et al., 2020). Correspondingly, transition approaches carry the most risk (Wilhelmi et al., 2017); they are often controversial (Neff & Larson, 2014), partly because of a lack of site-level guidance for determining the appropriate future species and provenances for a given region (Park & Talbot, 2018) and a general uncertainty surrounding how introduced species or genotypes may behave at a given site (Whittet et al., 2016; Wilhelmi et al., 2017).

Central to resilience and transition strategies is recognizing the functional responses associated with structural and compositional conditions created by a given set of silvicultural activities (Messier et al., 2015). This includes considering the response traits of species favored by a given practice, both in terms of their ability to persist in the face of changing climate regimes and their ability to respond and recover following future disturbances ( Biggs et al., 2020; Elmqvist et al., 2003). Although an understanding of certain functional traits, namely shade tolerance, growth rate, and reproductive mechanisms, has always guided silvicultural activities (Dean, 2012), the novelty of global change impacts requires a broader integration of traits, such as migration potential, that emphasizes the mechanisms conferring adaptive potential within and across species (Aubin et al., 2016; Yachi & Loreau, 1999). Obtaining and summarizing the relevant trait values for many species remain critical challenges in many regions. However, the development of indices that rank species on the basis of suites of traits associated with key sensitivities and responses, such as regeneration modes (e.g., sprouting ability, seed banking) and drought and fire tolerance (e.g., Fig. 13.2; Boisvert-Marsh et al., 2020), may prove useful in guiding future species selection for a given ecosystem.

Boisvert-Marsh et al. (2020), CC BY license

Groupings of species from eastern Canada having similar sensitivities and responses to drought (left blue column), migration (center green column), and fire (right brown column) on the basis of functional traits. Average tolerance and sensitivity are denoted by blue (tolerance) and red (sensitivity) symbols; larger symbols indicate more extreme values. A lack of a symbol indicates intermediate values or the lack of a clear trend. Modified from

3 Examples and Outcomes of Adaptation in Temperate and Boreal Ecosystems

The fast pace of climate change is particularly challenging because of the long lag between the evaluation of an adaptation strategy through field observations and the ability to recommend and implement the strategy at a broad scale (Biggs et al., 2009, 2020). As a result, decisions surrounding the regional deployment of adaptation strategies are most often based on simulation studies of future landscape dynamics under different management regimes and climate conditions (Duveneck & Scheller, 2015; Dymond et al., 2014; Hof et al., 2017). Numerous studies applying landscape simulation and forest planning models (e.g., LANDIS-II) have demonstrated the potential for recommended strategies. For example, the broad-scale deployment of mixed-species plantings increased the resilience of biomass stocks and volume flows in temperate and boreal systems (Duveneck & Scheller, 2015; Dymond et al., 2014, 2020). Nevertheless, a key limitation of simulation modeling, as it relates to operationalizing any given practice, is the inability to fully capture uncertainties in the future social acceptance of an approach (Seidl & Lexer, 2013), including from forest managers (Hengst-Ehrhart, 2019; Sousa-Silva et al., 2018). Therefore, it remains critical to support these model outcomes with field-based applications that include managers and broader societal perspectives.

As an alternative to model simulations, numerous studies have used dendrochronological techniques to retrospectively evaluate the ability of adaptation strategies to confer resilience to stressors and climate extremes (e.g., severe drought). This research approach has confirmed the utility of commonly applied silvicultural treatments, such as thinning for density management (Bottero et al., 2017; D'Amato et al. 2013; Sohn et al., 2016) and mixed-species management (Bauhus et al., 2017; Drobyshev et al., 2013; Metz et al., 2016; Vitali et al., 2018) at promoting resistance and resilience to past drought events and insect outbreaks. Additionally, retrospective work examining the drought sensitivity of white spruce (Picea glauca) within common garden experiments in Québec, Canada, demonstrated the potential for deploying planting stock from drier locales to enhance the resilience to drought in boreal systems (Depardieu et al., 2020). These studies have collectively affirmed potential strategies suggested for addressing global change (Park et al., 2014). However, such studies are limited in their ability to address novel, future climate and socioecological conditions that have no historical analog.

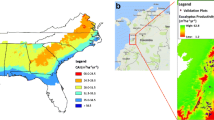

Over the past decades, there has been a proliferation of adaptation silviculture experiments and demonstrations in North America to address the need for forward thinking, field-based adaptation silviculture. These studies follow from the legacy of numerous, large-scale, operational ecological silviculture experiments established in boreal and temperate regions during the 1990s and 2000s (e.g., Brais et al., 2004; Hyvärinen et al., 2005; Seymour et al., 2006; Spence & Volney, 1999). The greatest concentration of these studies has been in the Great Lakes and northeastern regions of the United States largely through the efforts of the Climate Change Response Framework (Fig. 13.3; Janowiak et al., 2014).

Silvicultural experiments and demonstration areas evaluating various silvicultural adaptation strategies in the midwestern and northeastern United States as part of the Climate Change Response Framework (Janowiak et al., 2014). Since 2009, over 200 adaptation demonstrations have been established as part of this network, serving as early examples of how adaptation strategies can be operationalized across diverse forest conditions and ownership. Each area is designed with input from manager partners (i.e., co-produced) to ensure relevance to local ecological and operational contexts. Map obtained with permission from the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science (NIACS)

Syntheses of the applied adaptation strategies in a subset of demonstrations in this network underscore the influence of current forest conditions and prevailing management objectives on how climate adaptation is currently integrated into silvicultural prescriptions (Ontl et al., 2018). For example, in northern temperate and boreal regions of the network where intensive, historical land use has generated relatively homogeneous forest conditions (Schulte et al., 2007), adaptation strategies have largely focused on increasing the diversity of canopy-tree species and the structural complexity of these forests (Ontl et al., 2018). In contrast, adaptation strategies in fire-adapted forests in the temperate region largely focus on the restoration of woodland structures and the introduction of prescribed fires (Ontl et al., 2018) to counter the long-standing outcomes of fire exclusion, e.g., higher tree densities and a greater abundance of mesophytic species (Hanberry et al., 2014). Overall, most adaptation strategies used by managers to date are best categorized as resilience approaches, highlighting a general reluctance to accept the initial risks and costs of more experimental transition strategies, a sentiment reflected in surveys of forest managers in other portions of the United States (Scheller & Parajuli, 2018) and Europe (Sousa-Silva et al., 2018).

The above summary highlights that many adaptation strategies will likely build off prevailing silvicultural approaches in a region, particularly in the near term. Some regions, such as boreal Canada, in which silvicultural systems rely heavily on artificial regeneration—either as part of plantation systems or as a supplement to natural regeneration—will have much greater capacity to implement resilience and transition strategies that rely on artificial regeneration than regions having historically relied solely on natural regeneration (Pedlar et al., 2012). Nonetheless for the boreal region and other regions, operationalizing novel transition strategies is not only hampered by a lack of experience but also by a limited nursery infrastructure and breeding programs. These programs would allow for species and genotypic selection to match projected climate and disturbance conditions for a given location (cf. O'Neill et al. 2017) and produce sufficient quantities to influence practices widely.

In many cases, the trigger for a more widespread application of novel adaptation strategies will likely be the realization that forest conditions are rapidly advancing toward undesirable thresholds because of changing climate, invasive species, and altered disturbance regimes. For instance, a fairly rapid shift toward applying transition strategies is underway in the Northern Lake States region in response to the threat to native black ash (Fraxinus nigra) wetlands from the introduced emerald ash borer (Rissman et al., 2018). The emerald ash borer is moving into the region in response to warming winters, and the habitat for native trees able to potentially replace black ash is rapidly declining because of climate change. In this example, novel enrichment plantings of climate-adapted, non-host species are being used as part of silvicultural treatments aimed at diversifying areas currently dominated by the host species and thus sustain post-invasion ecosystem functions (D’Amato et al., 2018).

4 Landscape and Regional Allocation of Adaptation Strategies

In addition to regional variation in the application of stand-scale adaptation strategies, within-region variation in ownership, management objectives, and the ability to absorb risks associated with experimental adaptation strategies may require landscape-level zonation into different intensities of adaptation (Park et al., 2014). The landscape is an important scale for adaptation planning because (1) major ecological processes such as metapopulation dynamics, species migration, and many natural disturbances occur at this scale; (2) forest habitat loss and fragmentation can only be addressed at large spatial scales; and (3) forest planning, including annual allowable harvest calculations, is multifaceted and depends on a variety of premises of current and targeted biophysical states as well as land ownership, policy, decision mandates, and governance mechanisms operating at the landscape scale. Correspondingly, the zonation of landscapes and regions into different silvicultural regimes has long been advocated as a strategy to achieve a diversity of objectives across ownerships (Seymour & Hunter, 1992; Tappeiner et al., 1986). In terms of application, zoning approaches are especially suitable to large areas under single ownership and characterized by low population densities (Sarr & Puettmann, 2008), such as for many boreal regions.

In most regions, including the boreal portions of Canada and Europe, zonation approaches have been motivated by potential incongruities between historical, commodity-focused objectives and those focused on broader nontimber objectives, including the maintenance of native biodiversity and cultural values (Côté et al., 2010; Messier et al., 2009; Naumov et al., 2018). Within the context of these often conflicting objectives, the TRIAD zonation model (Seymour & Hunter, 1992), has been popularized in parts of boreal Canada as a potential strategy for achieving diverse objectives over large landholdings. With this approach, landscapes are generally divided into intensive regions, characterized by high-input, production-focused silviculture (e.g., plantations), and extensive regions, where less-intensive approaches, such as ecological silviculture (sensu Palik et al., 2020), are used to attain nontimber objectives (e.g., biodiversity conservation, aesthetics) while also providing an opportunity for timber production (Fig. 13.4a). The third component of the TRIAD model—unmanaged, ecological reserves—are designated to protect unique ecological and cultural resources, enhance landscape connectivity, and serve as natural benchmarks to inform ecosystem management practices in extensively managed areas (Montigny & MacLean, 2005).

(top) Forested landscape delineated according to TRIAD zonation (Seymour & Hunter, 1992), having zones of intensive production (white polygons), ecological reserves (dark green polygons), and extensive management in between. Shades of green within the extensive management zone indicate varying application levels of ecological silviculture (based on Palik et al., 2020). (bottom) Application of strategic, future-adapted planting across management intensities to generate functionally complex landscapes (sensu Messier et al., 2019); tree size depicts the level of deployed novel planting strategies, with intensive zones serving as central nodes of adaptation. Solid lines denote the functional connections between landscape elements, having similar response traits in planted species. Dashed lines represent long-term connections developed within unmanaged reserves, where no planting has occurred, because of the long-term colonization of the areas by future-adapted species planted in other portions of the landscape

With its associated varying levels of silvicultural intensity and investment, the TRIAD zonation model is a useful construct for considering the opportunities and constraints to operationalizing adaptation strategies across large portions of the boreal forest (Park et al., 2014). For instance, high-input adaptation strategies, such as establishing future-adapted plantations, may be restricted to areas where intensive silvicultural regimes have predominated historically, such as lands proximate to mills. For instance, in western Canada, climate-informed reforestation strategies are most successful at minimizing drought-related reductions in timber volumes when resistant species and genotypes are planted proximate to mills and transportation routes, as opposed to more extensive planting approaches (Lochhead et al., 2019). In contrast, the financial and access constraints of extensively managed areas and the increasing risks of severe disturbance impacts (Boucher et al., 2017) argue for the use of a portfolio approach in these areas; this portfolio includes lower input resilience and higher input transition strategies that build from ecological silvicultural strategies, e.g., natural disturbance-based silvicultural systems, attributed to extensive zones under the TRIAD model (D’Amato & Palik, 2021). A key difference from the historical application of ecological silviculture is the integration of the targeted planting of future-adapted species—as enrichment plantings in actively managed stands or after natural disturbances—to increase functional diversity over time (Halofsky et al., 2020).

The TRIAD approach, as initially conceived, focused mainly on maximizing within-zone function to balance regional wood production and biodiversity conservation goals within a regional landscape (Seymour & Hunter, 1992). The emphasis of adaptation silviculture on enhancing potential recovery mechanisms and distributing risk has placed greater focus on cross-scale, functional interactions between zones when allocating adaptation strategies (Craven et al., 2016; Gömöry et al., 2020; Messier et al., 2019). In particular, a critical aspect of adaptation zonation is the strategic deployment of approaches, such as mixed-species plantations or enrichment plantings, to functionally link forest stands across a landscape (Fig. 13.4b; Aquilué et al., 2020; Messier et al., 2019). Guiding these recommendations is a recognition of the importance of greater levels of functional complexity at multiple scales to generate landscape-level resilience to disturbances and climate change (Messier et al., 2019). This includes enhancing levels of functional connectivity across landscape elements to facilitate species migration and recovery from disturbance (Millar et al., 2007; Nuñez et al., 2013) and designating central stands or nodes (sensu Craven et al., 2016) to serve as regional source populations for future-adapted species and key functional traits (Fig. 13.4b). Although still largely conceptual, future assessments of landscape-level functional connectivity and diversity (Craven et al., 2016) may be useful for prioritizing locations where more risk-laden adaptation strategies, such as novel species plantings, should occur in a given region (Aquilué et al., 2020). Note, however, that the risks associated with these strategies include not only financial and production losses due to maladaptation of planted species or genotypes but also potential negative impacts on forest-dependent wildlife species. Therefore, it becomes increasingly critical to identify strategies that maximize future adaptation potential while minimizing negative impacts on the functions and biota associated with ecological reserves and other portions of the landscape (cf. Tittler et al., 2015).

5 Conclusions

The application of silviculture has always assumed a level of uncertainty and risk in terms of ecological outcomes and socioeconomic feasibility and acceptability (Palik et al., 2020). Despite this uncertainty and risk, traditional silviculture approaches, after centuries of implementation, are well supported by long-term experience and research in many regions in the world. In contrast, in the context of rapid and novel global change, including climate, forest loss, disturbance, and invasive species, there is now an urgency to expand silviculture strategies to include high-risk experimental approaches, even if they are not well supported by long-term experience and research. Moreover, these approaches can still rely on the same framework for addressing uncertainty and risk that foresters have always used and understood (Palik et al., 2020). Given general aversions to risk, most field applications of adaptation strategies to date have built on past experiences and existing silvicultural practices; these include applying intermediate treatments to build resistance to change and ecological silvicultural practices to increase resilience. Although modeling exercises are useful for exploring responses to novel experimental strategies, like assisted migration, field experience with these approaches is currently limited, particularly at the operational scale. Given these challenges, we identify the following key needs to advance adaptation silviculture into widespread practice in forest landscapes:

-

Integration of geospatial databases with disturbance and climate models to increase the spatial resolution of regional vulnerability assessments and allow a site-level determination of urgency and the appropriateness of adaptation strategies

-

Improvement of existing modeling frameworks to better account for novel species interactions and potential feedbacks between future socioeconomic and ecological dynamics and adaptation practices over time

-

Strategic investment in operational-scale adaptation experiments and demonstrations across regions, ecosystems, and site conditions, including high-risk strategies

-

Coordination of the abovementioned experiments, trials, and demonstrations to allow for rapid information sharing among stakeholders and the adjustment of practices in response to observed outcomes and changing environmental dynamics

-

Regional assessments of nursery capacity and novel stock availability in the context of adaptation plantings to prioritize investment in the propagation and wide distribution of desirable species and genotypes

-

Continued development of trait-based indices to assist with operationalizing adaptation strategies focused on enhancing functional complexity across scales

-

Consideration of relevant scales for the provision of ecosystem services to provide flexibility when applying adaptation strategies

Global change and its impacts appear to be greatly outpacing adaptation science, and investments in infrastructure must adapt. However, working to prioritize these scientific needs and investments, including deploying adaptation strategies in the near term that are compatible with current management frameworks, is critical to avoid crossing undesirable ecological thresholds. Seeing these rapidly approaching thresholds should serve as the primary motivating factor for moving forward with widespread adaptation to ensure the long-term sustainable production of goods and services.

References

Alotaibi, K., Ghumman, A. R., Haider, H., et al. (2018). Future predictions of rainfall and temperature using GCM and ANN for arid regions: A case study for the Qassim region. Saudi Arabia Water, 10, 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10091260.

Aquilué, N., Filotas, É., Craven, D., et al. (2020). Evaluating forest resilience to global threats using functional response traits and network properties. Ecological Applications, 30, e02095. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2095.

Aubin, I., Boisvert-Marsh, L., Kebli, H., et al. (2018). Tree vulnerability to climate change: Improving exposure-based assessments using traits as indicators of sensitivity. Ecosphere, 9, e02108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2108.

Aubin, I., Munson, A. D., Cardou, F., et al. (2016). Traits to stay, traits to move: A review of functional traits to assess sensitivity and adaptive capacity of temperate and boreal trees to climate change. Environmental Reviews, 24, 164–186. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2015-0072.

Bauhus, J., Forrester, D. I., Gardiner, B., et al. (2017). Ecological stability of mixed-species forests. In H. Pretzsch, D. I. Forrester, & J. Bauhus (Eds.), Mixed-species forests: Ecology and management (pp. 337–382). Springer.

Bergeron, Y., Leduc, A., Joyal, C., et al. (1995). Balsam fir mortality following the last spruce budworm outbreak in northwestern Quebec. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 25, 1375–1384. https://doi.org/10.1139/x95-150.

Biggs, C. R., Yeager, L. A., Bolser, D. G., et al. (2020). Does functional redundancy affect ecological stability and resilience? A Review and Meta-Analysis. Ecosphere, 11, e03184. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3184.

Biggs, R., Carpenter, S. R., & Brock, W. A. (2009). Turning back from the brink: Detecting an impending regime shift in time to avert it. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 826–831. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0811729106.

Boisvert-Marsh, L., Royer-Tardif, S., Nolet, P., et al. (2020). Using a trait-based approach to compare tree species sensitivity to climate change stressors in eastern Canada and inform adaptation practices. Forests, 11, 989. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090989.

Bottero, A., D’Amato, A. W., Palik, B. J., et al. (2017). Density-dependent vulnerability of forest ecosystems to drought. Journal of Applied Ecology, 54, 1605–1614. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12847.

Boucher, Y., Auger, I., Noël, J., et al. (2017). Fire is a stronger driver of forest composition than logging in the boreal forest of eastern Canada. Journal of Vegetation Science, 28, 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12466.

Brais, S., Harvey, B. D., Bergeron, Y., et al. (2004). Testing forest ecosystem management in boreal mixedwoods of northwestern Quebec: Initial response of aspen stands to different levels of harvesting. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 34, 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-144.

Brokaw, N., & Busing, R. T. (2000). Niche versus chance and tree diversity in forest gaps. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 15, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01822-X.

Butler, B. W., Ottmar, R. D., Rupp, T. S., et al. (2013). Quantifying the effect of fuel reduction treatments on fire behavior in boreal forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 43, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2012-0234.

Camarero, J., Gazol, A., Sangüesa-Barreda, G., et al. (2018). Forest growth responses to drought at short- and long-term scales in Spain: Squeezing the stress memory from tree rings. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00009.

Campbell, E. M., MacLean, D. A., & Bergeron, Y. (2008). The severity of budworm-caused growth reductions in balsam fir/spruce stands varies with the hardwood content of surrounding forest landscapes. Forestry Sciences, 54, 195–205.

Chmura, D. J., Anderson, P. D., Howe, G. T., et al. (2011). Forest responses to climate change in the northwestern United States: Ecophysiological foundations for adaptive management. Forest Ecology and Management, 261(7), 1121–1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.12.040.

Christensen, N. L., Bartuska, A. M., Brown, J. H., et al. (1996). The report of the Ecological Society of America Committee on the scientific basis for ecosystem management. Ecological Applications, 6, 665–691. https://doi.org/10.2307/2269460.

Côté, P., Tittler, R., Messier, C., et al. (2010). Comparing different forest zoning options for landscape-scale management of the boreal forest: Possible benefits of the TRIAD. Forest Ecology and Management, 259, 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.10.038.

Craven, D., Filotas, E., Angers, V. A., et al. (2016). Evaluating resilience of tree communities in fragmented landscapes: Linking functional response diversity with landscape connectivity. Diversity and Distributions, 22, 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12423.

D’Amato, A. W., Bradford, J. B., Fraver, S., et al. (2013). Effects of thinning on drought vulnerability and climate response in north temperate forest ecosystems. Ecological Applications, 23, 1735–1742. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0677.1.

D’Amato, A. W., & Palik, B. J. (2021). Building on the last “new” thing: Exploring the compatibility of ecological and adaptation silviculture. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 51, 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2020-0306.

D’Amato, A. W., Palik, B. J., Slesak, R. A., et al. (2018). Evaluating adaptive management options for black ash forests in the face of emerald ash borer invasion. Forests, 9, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9060348.

Daly, C., Conklin, D. R., & Unsworth, M. H. (2010). Local atmospheric decoupling in complex topography alters climate change impacts. International Journal of Climatology, 30, 1857–1864. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2007.

Dean, T. J. (2012). A simple case for the term “tolerance.” Journal of Forestry, 110, 463–464. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.12-039.

Depardieu, C., Girardin, M. P., Nadeau, S., et al. (2020). Adaptive genetic variation to drought in a widely distributed conifer suggests a potential for increasing forest resilience in a drying climate. New Phytologist, 227, 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16551.

Donoso, P. J., Puettmann, K. J., D’Amato, A. W., et al. (2020). Short-term effects of variable-density thinning on regeneration in hardwood-dominated temperate rainforests. Forest Ecology and Management, 464, 118058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118058.

Drobyshev, I., Gewehr, S., Berninger, F., et al. (2013). Species specific growth responses of black spruce and trembling aspen may enhance resilience of boreal forest to climate change. Journal of Ecology, 101, 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12007.

Duveneck, M. J., & Scheller, R. M. (2015). Climate-suitable planting as a strategy for maintaining forest productivity and functional diversity. Ecological Applications, 25, 1653–1668. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0738.1.

Dymond, C. C., Giles-Hansen, K., & Asante, P. (2020). The forest mitigation-adaptation nexus: Economic benefits of novel planting regimes. Forest Policy and Economics, 113, 102124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102124.

Dymond, C. C., Tedder, S., Spittlehouse, D. L., et al. (2014). Diversifying managed forests to increase resilience. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 44, 1196–1205. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2014-0146.

Elkin, C., Giuggiola, A., Rigling, A., et al. (2015). Short- and long-term efficacy of forest thinning to mitigate drought impacts in mountain forests in the European Alps. Ecological Applications, 25, 1083–1098. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0690.1.

Elmqvist, T., Folke, C., Nystrom, M., et al. (2003). Response diversity, ecosystem change, and resilience. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 1, 488–494. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0488:RDECAR]2.0.CO;2.

Etterson, J. R., Cornett, M. W., White, M. A., et al. (2020). Assisted migration across fixed seed zones detects adaptation lags in two major North American tree species. Ecological Applications, 30, e02092. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2092.

Flint, C. G., McFarlane, B., & Müller, M. (2009). Human dimensions of forest disturbance by insects: An international synthesis. Environmental Management, 43, 1174–1186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9193-4.

Frey, S. J. K., Hadley, A. S., Johnson, S. L., et al. (2016). Spatial models reveal the microclimatic buffering capacity of old-growth forests. Science Advances, 2(4), e1501392. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501392.

Gauthier, S., Bernier, P., Burton, P. J., et al. (2014). Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the managed Canadian boreal forest. Environmental Reviews, 22, 256–285. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2013-0064.

Gömöry, D., Krajmerová, D., Hrivnák, M., et al. (2020). Assisted migration vs. close-to-nature forestry: what are the prospects for tree populations under climate change? Central European Forestry Journal, 66(2), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.2478/forj-2020-0008.

Gunderson, L. H. (2000). Ecological resilience-in theory and application. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 31, 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.425.

Halofsky, J. E., Peterson, D. L., & Harvey, B. J. (2020). Changing wildfire, changing forests: The effects of climate change on fire regimes and vegetation in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Fire Ecology, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-019-0062-8.

Hanberry, B. B., Kabrick, J. M., & He, H. S. (2014). Densification and state transition across the Missouri Ozarks landscape. Ecosystems, 17, 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9707-7.

Hemery, G. (2008). Forest management and silvicultural responses to projected climate change impacts on European broadleaved trees and forests. International Forestry Review, 10, 591–607. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.10.4.591.

Hengst-Ehrhart, Y. (2019). Knowing is not enough: Exploring the missing link between climate change knowledge and action of German forest owners and managers. Annals of Forest Science, 76, 94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0878-z.

Hof, A. R., Dymond, C. C., & Mladenoff, D. J. (2017). Climate change mitigation through adaptation: The effectiveness of forest diversification by novel tree planting regimes. Ecosphere, 8, e01981. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1981.

Hyvärinen, E., Kouki, J., Martikainen, P., et al. (2005). Short-term effects of controlled burning and green-tree retention on beetle (Coleoptera) assemblages in managed boreal forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 212, 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.03.029.

Janowiak, M. K., Swanston, C. W., Nagel, L. M., et al. (2014). A practical approach for translating climate change adaptation principles into forest management actions. Journal of Forestry, 112, 424–433. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.13-094.

Johnstone, J. F., Allen, C. D., Franklin, J. F., et al. (2016). Changing disturbance regimes, ecological memory, and forest resilience. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1311.

Johnstone, J. F., Rupp, T. S., Olson, M., et al. (2011). Modeling impacts of fire severity on successional trajectories and future fire behavior in Alaskan boreal forests. Landscape Ecology, 26, 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-011-9574-6.

Kurz, W. A., Stinson, G., Rampley, G. J., et al. (2008). Risk of natural disturbances makes future contribution of Canada’s forests to the global carbon cycle highly uncertain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 1551–1555. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708133105.

Landres, P. B., Morgan, P., & Swanson, F. J. (1999). Overview of the use of natural variability concepts in managing ecological systems. Ecological Applications, 9(4), 1179–1188. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(1999)009[1179:OOTUON]2.0.CO;2.

Lochhead, K., Ghafghazi, S., LeMay, V., et al. (2019). Examining the vulnerability of localized reforestation strategies to climate change at a macroscale. Journal of Environmental Management, 252, 109625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109625.

Messier, C., Bauhus, J., Doyon, F., et al. (2019). The functional complex network approach to foster forest resilience to global changes. Forest Ecosystems, 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-019-0166-2.

Messier, C., Puettmann, K., Chazdon, R., et al. (2015). From management to stewardship: Viewing forests as complex adaptive systems in an uncertain world. Conservation Letters, 8, 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12156.

Messier, C., Tittler, R., Kneeshaw, D. D., et al. (2009). TRIAD zoning in Quebec: Experiences and results after 5 years. The Forestry Chronicle, 85, 885–896. https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc85885-6.

Metz, J., Annighöfer, P., Schall, P., et al. (2016). Site-adapted admixed tree species reduce drought susceptibility of mature European beech. Global Change Biology, 22, 903–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13113.

Meyers, L. A., & Bull, J. J. (2002). Fighting change with change: Adaptive variation in an uncertain world. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 17, 551–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02633-2.

Millar, C. I., Stephenson, N. L., & Stephens, S. L. (2007). Climate change and forests of the future: Managing in the face of uncertainty. Ecological Applications, 17, 2145–2151. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1715.1.

Montigny, M. K., & MacLean, D. A. (2005). Using heterogeneity and representation of ecosite criteria to select forest reserves in an intensively managed industrial forest. Biological Conservation, 125, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.03.028.

Muller, J. J., Nagel, L. M., & Palik, B. J. (2019). Forest adaptation strategies aimed at climate change: Assessing the performance of future climate-adapted tree species in a northern Minnesota pine ecosystem. Forest Ecology and Management, 451, 117539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117539.

Mumby, P. J., Chollett, I., Bozec, Y. M., et al. (2014). Ecological resilience, robustness and vulnerability: How do these concepts benefit ecosystem management? Current Opinion in Environment Sustainability, 7, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.021.

Nagel, L. M., Palik, B. J., Battaglia, M. A., et al. (2017). Adaptive silviculture for climate change: A national experiment in manager-scientist partnerships to apply an adaptation framework. Journal of Forestry, 115, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.16-039.

Naumov, V., Manton, M., Elbakidze, M., et al. (2018). How to reconcile wood production and biodiversity conservation? The Pan-European boreal forest history gradient as an “experiment.” Journal of Environmental Management, 218, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.03.095.

Navarro, L., Morin, H., Bergeron, Y., et al. (2018). Changes in spatiotemporal patterns of 20th century spruce budworm outbreaks in eastern Canadian boreal forests. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9, 1905. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01905.

Neff, M. W., & Larson, B. M. H. (2014). Scientists, managers, and assisted colonization: Four contrasting perspectives entangle science and policy. Biological Conservation, 172, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.02.001.

Nitschke, C. R., & Innes, J. L. (2008). Integrating climate change into forest management in South-Central British Columbia: An assessment of landscape vulnerability and development of a climate-smart framework. Forest Ecology and Management, 256, 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.04.026.

Nolet, P., Doyon, F., & Messier, C. (2014). A new silvicultural approach to the management of uneven-aged Northern hardwoods: Frequent low-intensity harvesting. Forestry, 87, 39–48.

Nuñez, T. A., Lawler, J. J., McRae, B. H., et al. (2013). Connectivity planning to address climate change. Conservation Biology, 27, 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12014.

O’Hara, K. L., & Ramage, B. S. (2013). Silviculture in an uncertain world: Utilizing multi-aged management systems to integrate disturbance. Forestry, 86, 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpt012.

O’Neill, G.A., Wang, T., Ukrainetz, N., et al. (2017). A proposed climate-based seed transfer system for British Columbia. Technical Report 099. Victoria: Province of British Columbia.

Olson, M. E., Soriano, D., Rosell, J. A., et al. (2018). Plant height and hydraulic vulnerability to drought and cold. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 7551–7556. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721728115.

Ontl, T. A., Swanston, C., Brandt, L. A., et al. (2018). Adaptation pathways: Ecoregion and land ownership influences on climate adaptation decision-making in forest management. Climatic Change, 146, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1983-3.

Palik, B. J., D’Amato, A. W., Franklin, J. F., et al. (2020). Ecological silviculture: Foundations and applications. Waveland Press.

Park, A., Puettmann, K., Wilson, E., et al. (2014). Can boreal and temperate forest management be adapted to the uncertainties of 21st century climate change? Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 33, 251–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.2014.858956.

Park, A., & Talbot, C. (2018). Information underload: Ecological complexity, incomplete knowledge, and data deficits create challenges for the assisted migration of forest trees. BioScience, 68, 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biy001.

Pedlar, J. H., McKenney, D. W., Aubin, I., et al. (2012). Placing forestry in the assisted migration debate. BioScience, 62, 835–842. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.10.

Price, D. T., Alfaro, R. I., Brown, K. J., et al. (2013). Anticipating the consequences of climate change for Canada’s boreal forest ecosystems. Environmental Reviews, 21, 322–365. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2013-0042.

Puettmann, K. J. (2011). Silvicultural challenges and options in the context of global change: Simple fixes and opportunities for new management approaches. Journal of Forestry, 109, 321–331.

Puettmann, K. J., Coates, K. D., & Messier, C. C. (2009). A critique of silviculture: Managing for complexity. Island Press.

Puettmann, K. J., & Messier, C. (2020). Simple guidelines to prepare forests for global change: The dog and the frisbee. Northwest Science, 93(3–4), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.3955/046.093.0305.

Rissman, A. R., Burke, K. D., Kramer, H. A. C., et al. (2018). Forest management for novelty, persistence, and restoration influenced by policy and society. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 16, 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1818.

Rowe, J. S. (1983). Concepts of fire effects on plant individuals and species. In R. W. Wein & D. A. MacLean (Eds.), The role of fire in northern circumpolar ecosystems (pp. 135–153). John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Ruehr, N. K., Grote, R., Mayr, S., et al. (2019). Beyond the extreme: Recovery of carbon and water relations in woody plants following heat and drought stress. Tree Physiology, 39, 1285–1299. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpz032.

Sarr, D. A., & Puettmann, K. J. (2008). Forest management, restoration, and designer ecosystems: Integrating strategies for a crowded planet. Ecoscience, 15, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.2980/1195-6860(2008)15[17:FMRADE]2.0.CO;2.

Scheller, R. M., & Parajuli, R. (2018). Forest management for climate change in New England and the Klamath ecoregions: Motivations, practices, and barriers. Forests, 9, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9100626.

Schulte, L. A., Mladenoff, D. J., Crow, T. R., et al. (2007). Homogenization of northern US Great Lakes forests due to land use. Landscape Ecology, 22, 1089–1103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-007-9095-5.

Seidl, R., & Lexer, M. J. (2013). Forest management under climatic and social uncertainty: Trade-offs between reducing climate change impacts and fostering adaptive capacity. Journal of Environmental Management, 114, 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.09.028.

Seidl, R., Schelhaas, M. J., Rammer, W., et al. (2014). Increasing forest disturbances in Europe and their impact on carbon storage. Nature Climate Change, 4, 806–810. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2318.

Seidl, R., Thom, D., Kautz, M., et al. (2017). Forest disturbances under climate change. Nature Climate Change, 7(6), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3303.

Seymour, R. S., Guldin, J., Marshall, D., et al. (2006). Large-scale, long-term silvicultural experiments in the United States: Historical overview and contemporary examples. Allgemeine Forst Jagdzeitung, 177, 104–112.

Seymour, R. S., & Hunter, M. L. (1992). New forestry in eastern spruce-fir forests: Principles and applications to Maine. Orono: University of Maine.

Smith, D. M. (1962). The practice of silviculture (7th ed.). Wiley.

Sohn, J. A., Hartig, F., Kohler, M., et al. (2016). Heavy and frequent thinning promotes drought adaptation in Pinus sylvestris forests. Ecological Applications, 26, 2190–2205. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1373.

Sousa-Silva, R., Verbist, B., Lomba, Â., et al. (2018). Adapting forest management to climate change in Europe: Linking perceptions to adaptive responses. Forest Policy and Economics, 90, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.01.004.

Spence, J. R., & Volney, W. J. A. (1999). EMEND: Ecosystem management emulating natural disturbance. 1999–14 Edmonton: Sustainable Forest Management Network.

Swanston, C. W., Janowiak, M. K., & Brandt, L. A., et al. (2016). Forest adaptation resources: climate change tools and approaches for land managers (General Technical Report. NRS-GTR-87–2) (p. 161). Newtown Square: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station.

Tappeiner, J. C., Knapp, W. H., Wiermann, C. A., et al. (1986). Silviculture: The next 30 years, the past 30 years. Part II. The Pacific Coast. Journal of Forestry, 84, 37–46.

Thorne, J. H., Gogol-Prokurat, M., Hill, S., et al. (2020). Vegetation refugia can inform climate-adaptive land management under global warming. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 18, 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2208.

Tittler, R., Filotas, É., Kroese, J., et al. (2015). Maximizing conservation and production with intensive forest management: It’s all about location. Environmental Management, 56, 1104–1117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0556-3.

Vitali, V., Forrester, D. I., & Bauhus, J. (2018). Know your neighbours: Drought response of Norway spruce, silver fir and Douglas fir in mixed forests depends on species identity and diversity of tree neighbourhoods. Ecosystems, 21, 1215–1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0214-0.

Whittet, R., Cavers, S., Cottrell, J., et al. (2016). Seed sourcing for woodland creation in an era of uncertainty: An analysis of the options for Great Britain. Forestry, 90, 163–173.

Wiens, J. A., Stralberg, D., Jongsomjit, D., et al. (2009). Niches, models, and climate change: Assessing the assumptions and uncertainties. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 19729–19736. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901639106.

Wilhelmi, N. P., Shaw, D. C., Harrington, C. A., et al. (2017). Climate of seed source affects susceptibility of coastal Douglas-fir to foliage diseases. Ecosphere, 8(12), e02011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2011.

Yachi, S., & Loreau, M. (1999). Biodiversity and ecosystem productivity in a fluctuating environment: The insurance hypothesis. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96, 1463–1468. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.4.1463.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

D’Amato, A.W., Palik, B.J., Raymond, P., Puettmann, K.J., Girona, M.M. (2023). Building a Framework for Adaptive Silviculture Under Global Change. In: Girona, M.M., Morin, H., Gauthier, S., Bergeron, Y. (eds) Boreal Forests in the Face of Climate Change. Advances in Global Change Research, vol 74. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15988-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15988-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15987-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15988-6

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)