Abstract

This chapter compares the evolution of day-to-day, informal, workplace learning and work-based training arrangements in the metals sector in Bulgaria and Spain’s Basque region. The latter’s advanced, industrialised economic model is rather different from other Spanish regions. Basque country institutions successfully link vocational education with labour market needs; Bulgaria’s state educational system is poor at delivering skills. The Basque studies are both in the region’s important cooperative sector. The Bulgarian companies (both domestic subsidiaries of multinationals) developed in global value chains; they have recently introduced in-house training to cope with a shortage of qualified labour. Using qualitative methods, the chapter shows how organisational and individual agency provide space for informal workplace learning and what outcomes this has for early career workers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The chapter compares the evolution of day-to-day (informal) workplace learning and the work-based training arrangements in the metal sector in Bulgaria and in Spain, specifically the Basque region. Based on the literature about European social models (Sapir, 2006; Gallie, 2007; Delteil & Kirov, 2016), Bulgaria and Spain belong to the group of Post-Communist and respectively Mediterranean States, with the Basque region being quite different from other Spanish regions, due to its advanced industrialised economic model, which requires an efficient skills provision system. While in the Basque country system, the link between the labour market needs and vocational education is successfully mediated by institutions, Bulgaria represents an example of the weakness of the state educational system in delivering the necessary skills. Moreover, within the Basque region, the cooperative sector is still of high significance and therefore two cooperatives are chosen for in-depth study. Growing up in the global value chain, Bulgarian companies have recently started to develop in-house training arrangements in order to cope with the deficit of qualified labour. This process is observed both in domestic companies and subsidiaries of multinational companies. The empirical data for the analysis was collected within the framework of the Enliven project.

The objective of this chapter is to investigate the workplace learning practices in the European metal sector,Footnote 1 on the basis of four case studies in two countries. While complex manufacturing is undoubtedly increasingly needed for the economic development of Europe, the supply of skills and the integration of early career employees by the industry are problematic. The metal sector is one of the most important contributors to the European Union’s manufacturing industry (Alessandrini et al., 2017). The manufacture of metal products, except machinery and equipment, together with the manufacture of machinery and equipment include almost seven million employees in more than 480,000 companies in the European Union in 2016.Footnote 2 The value added by these subsectors is about one-fifth of the total value added in European manufacturing.

However, beyond the overall figures, the two above-mentioned subsectors hide a diversity of situations in terms of technological development, work organisation patterns and use of routine or non-routine work, labour productivity and value added. They include a wide range of companies, from very simple producers of metal products (situated mainly in Southern and Eastern Europe) to very complex companies, leaders in their respective value chains. Within the theoretical perspective of the value chain approach (Gereffi et al., 2005), the position of countries and companies in the respective chains is dynamic and can rise or fall. This dynamic perspective is important in understanding technological and organisational changes and the related dynamism of workplace learning practices. The two countries under scrutiny, Bulgaria and Spain, represent different configurations in these value chains. In the case of Bulgaria, companies are often integrated mainly as low-wage producers, either within the value chains of large European Union-based multinationals or as independent subcontractors to leading European Union metal and machinery producers. Those Bulgarian companies have gradually moved upward on the value chains, engaging in more complex tasks and investing in more sophisticated technologies and therefore demanding higher skills. The Spanish companies from the Basque region are highly specialised in complex machine building, delivering tailored products. The Spanish machine tool sector is the third largest producer and exporter in the European Union (just behind Germany and Italy) and is ranked ninth in the world. The vast majority (75% according to some reports) of this manufacturing activity is located in the Basque Country, where the enterprises studied in this chapter are located.

This diversity of situations within this sector also reflects the interplay between the skills acquisition provided by the educational system, the initial vocation education and training system and the work-based learning arrangements (Boyadjieva et al., 2012). In some countries, the cooperation between the worlds of education and work is well developed, as it is the case in the Basque region (López-Gereñu, 2018), while in others, such as the region of Bulgaria under study in this chapter, the formal education system is not able to provide the required skills for a number of reasons, including the lack of specialised vocational education and training classes, the low motivation of pupils and so on (Kirov, 2018) and therefore companies count mainly on workplace learning to train the early-career workers.

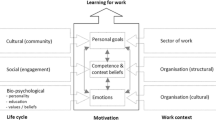

Based on the theoretical framework developed for the purposes of the Enliven project (see Chaps. 10 and 15), the chapter addresses this interplay on the basis of the bounded agency model (Evans, 2007). According to Evans (2007: 17), ‘Bounded agency is socially situated agency, influenced but not determined by environments and emphasizing internalized frames of reference as well as external actions’. The concept of ‘organisational agency’ is therefore used—analogously to individual agency—to give emphasis to the choices made by a particular organisation (ENLIVEN, 2020a). In this model, the structural (organisational) choices provide a space for individual agency.

More concretely, the following key questions are addressed in the chapter. First, how do organisations apply their agency in shaping workplaces, thereby unleashing or inhibiting their learning potential? Second, how do organisations apply their agency in structuring early career pathways? Finally, we address the question of how the organisation‘s decisions on workplace design, workplace learning, career structuration and human resource management impact on early career workers’ agency to learn in the workplace and beyond.

We are interested in workplace learning, understood as learning available in day-to-day work experience and the related forms of relating to others and belonging to groups. With organisational agency, the focus lies within the difference put into motion by particular decisions, which an organisation makes despite similar organisations under equivalent conditions opting for different solutions (see Chap. 10).

Overview of Cases Studied

The empirical work for this analysis has been carried out in the framework of the European comparative research project Enliven.Footnote 3 Four case studies have been undertaken in the metal sector, two in the Basque Country and two in Bulgaria. The main characteristics of the organisations are presented in Table 12.1. The two Spanish cases, medium-sized companies, are cooperatives, founded respectively in the 1950s and 1960s. The two Bulgarian cases are private companies, one established in 1992 and owned by its founders, the other established in 1972 as a state-owned company and then privatised by a foreign investor in 2003.

The methodology used for the case studies was qualitative. Two rounds of interviews were conducted with both managers and early career workers in 2017 and 2018. Up to four managers (the line manager, the human resources director and the president) and four early career workers were involved from each organisation in Spain. The characteristics of the participants as early career workers are presented in the project report (ENLIVEN, 2020a, b). In Bulgaria, in total ten interviews have been carried out in the case of BG1 and eight in the case of BG2. The information gathered in the interviews was deductively coded according to the framework of the study. In the case of early career workers, the information was also represented in life biography vignettes. The data collection was reinforced by desk research and action research with the participating companies. More details on the methodological framework is provided in Chap. 10 and in Appendix 1.

How Does Organisational Agency Shape the Learning Potential of Workplaces in the Metal Sector?

The theoretical understanding sustaining the analysis is that day-to-day informal workplace learning is impacted both by the agency of the organisation (company) and by the individual choices to act on (or not) the opportunities provided by organisations, as well as the dynamic interaction between the individual and organisational agencies. For this reason, we examine first the organisational agency and second how individuals use (or not) the learning opportunities.

Agency in Shaping Workplaces and Their Learning Potential

‘Organisational agency’ impacts on the learning potential available in the workplace in many ways (see Chap. 10). The main elements considered here are the division of labour and work structures, the job design and job ladders and the career structuration.

In Bulgaria, the two case studies examined represent two typical configurations for the Bulgarian Metal sector, one being a local medium-size company (BG1) and the other a subsidiary of a multinational company with European origins (BG2). Both produce metal details that are delivered to their contractors (external or internal, in the case of the multinational company) in order to be further utilised in the production of machines or machine components in other locations of the respective value chains. The work organisation in both cases follows an approach dominated by Taylorist organisation (rather typical for Bulgarian companies in this sector), but with (increasing) introduction of elements of lean production. Work is mainly routine. In both cases, the material (metal) is introduced on the production site, cut and then submitted to a series of manipulations. In addition, BG2 has some structures focused on the continuous improvement of the manufacturing process.

The key principles for designing jobs depend on organisational structure frequently adopted in Bulgaria. Both in the local company and the multinational company, new jobs are made available only if there is a need to add new machines. Production employees are expected to specialise on the respective machine (mainly CNCFootnote 4) to which they are assigned. In the examined company there are various narrowly defined jobs (specialisation on the machine) with some job ladders from less to more complex machines, but rarely to other types of machines or to first line management: ‘Basically, when we appoint a new collaborator, from the first day... he is already directly engaged in production and we are all there to help the production’ (BG2_M1_1_985); ‘Before the person starts, I know beforehand at what machine he must start working’ (BG2_M1_1_1000).

The two Basque companies belong to an important cooperative group and are well positioned in the respective value chain, bringing their social capital to a key component of the regional innovation system (Landabaso et al., 2003). The cooperatives’ objective is not to enrich the business owner but to achieve sustainable growth and bring well-being to the workers and the social fabric of the area where they are located. This is possible through collaboration and mutual aid between their members and the creation of a common heritage that cannot be divided (Martínez, 2009). Cooperative enterprises have similar business cultures, though their different environments, products and markets condition their individual strategies (Bakaikoa et al., 2004). Workers who join cooperatives do so for life, so cooperative staff members have a long-term vision for their careers. They show a conscious commitment to cooperate and progress together (Williams, 2007), taking responsibility for themselves, their colleagues and society (Kasmir, 1999).

The jobs studied, from low-skilled to high-skilled, are designed according to the preferences and needs of the organisation. They specialise in ‘turnkey products’, designed ad-hoc for the client and with high added value (organisational work within a project-based, customer-orientated‚ adhocracy, with ‘turnkey’ products). In some products, they are world leaders. Higher levels of skills (with higher ranked credentials) allow for faster progression on job ladders.

The links between jobs are constant, as they are team workers with multiple skills. Their professional roles are stable, changing from professional (expert) roles to managerial ones. New workers have a short induction phase in tightly defined jobs, with multi-skilling (for groups of jobs) and additional skills as they move up the job ladder. They start with less demanding tasks, moving on to more demanding tasks; starting with some specialisation and broadening the areas of expertise. They learn how good work is done by relying on peers, supervisors, and meetings to analyse unexpected events. In both companies, non-routine work predominates, as different products are designed and produced for each client.

Workers are expected to take part in a high level of customer relations (over 93% of products are exported); jobs are not defined according to stable patterns but constantly adapted to clients’ different projects; workers have professional training in the company and learn languages so they can communicate with international clients. They assist customers in product design (turnkey) and its implementation in the customers’ countries. The most highly recognised workers in particular fields of expertise teach others, acting as mentors. Engineers work with employees in the workshop, sharing workspaces side by side, facilitating mutual learning and exchange of tacit knowledge. Each project has a person in charge who assumes responsibility for the project vis-à-vis the client.

Although there is a high demand for workplace learning during quite a long incorporation (‘survival’) phase, spanning several months or even years, the additional learning requires individual initiative and a strong commitment to the company. The organisation therefore incorporates a talent management strategy to elicit a high level of commitment.

In the Bulgarian companies, we observed a transition in the provision of learning practices. This transition, which probably also applies to other manufacturing subsectors, was based on the formalisation of learning provision through training centres rather than (guided) on-the-job training (achieved mainly through mentorship by experienced workers). The emerging enlargement of the training curricula (theoretical courses, some soft skills, programming and so on) contrasted with the previous focus on technical skills. This change was demand-driven and influenced by factors such as an upgrade, from simple operations to more complex metal working, in the global value chain. What is surprising is that this process occurred almost simultaneously both in multinational subsidiaries and in local small and medium enterprises. Even if only part of the early career workers’ cohort is affected by this greater emphasis on formalised training, overall perspectives in workplace learning are changing. In company BG1, training was formerly delivered only on-the-job, sporadically and in case of particular need, such as with a new hire or the acquisition of new machines. Since the recent launch of the training centre, it became more formalised, mixing theoretical and practical training, though the employees enrolled remained a minority. In September 2017, BG2 also inaugurated a modern training centre at the factory. This trains employees and pupils in initial education: in this company, both became important priorities during its recent expansion (Table 12.2).

In Spain’s Basque country, cooperatives—whose employees are at the same time owners of the company—have a particular position, distinct from other companies. Their corporate tax rate is much lower than for public or private companies. Cooperative workers neither contribute to employment training funds nor benefit from subsidised training. They have typically created their own research and training centres; there is also a cooperative university. The latter’s origin lie in vocational training and, probably because of this and because the cooperatives constitute their own ecosystem, relations between cooperatives and training institutions are close. Training for professionals has been nourished by the good relations between training centres and companies, and by in-company traineeships (more common than in other universities). Though of relatively short duration, it is orientated to specific needs and more suitable for the continuous learning of workers. Staff consider that, as it is paid for by the company itself, the courses are more demanding, effective and responsive to needs. Even in small and medium companies, the incorporation of a practical module meant an exchange of information and assessment of the training provided in the centre. This often facilitated the adaptation of training programmes and joint design and implementation of new programmes, such as dual programmes on an alternating basis and specialised programmes, which responded to company demands. Since the first dual training programme in the Basque Autonomous Community, Ikasi eta Lan, started in 2008 in response to business demand, supply has evolved. The Basque model of dual vocational training on an alternating basis now allows for key aspects of business competitiveness, such as specialisation, internationalisation and innovation, to be incorporated into training, in collaboration with companies and their research and development departments, and with research and development centres or other agents in the Basque vocational training system (López-Gereñu, 2018).

Comparison of the Bulgarian and Spanish cases in terms of organisational agency suggests huge differences in the preferred ways of organising work between the two countries’ metal sectors. In Bulgaria, training is emerging and expanding, despite an organisational profile combining Tayloristic and lean elements. The model of on-the-job-training remains dominant, but in parallel, formalised training through training centres, providing theoretical skills, is emerging. Training in soft skills and languages is marginal and mainly confined to multinational company subsidiaries. In the Spanish case, workplace learning is massive and supported by provision of non-formal training, such as in foreign languages (given the importance of customer support in turnkey products and international clients). In the Basque Country, the companies themselves have played an important role in improving vocational training. It is thus important to highlight the role workplace training has played in revitalising relations between training centres and companies, with centre tutors and company instructors as key figures (López-Gereñu, 2018).

How Organisational Agency in Human Resource Management Structures Organisations’ Perceptions and Preferences for Learning Policies

Human resource management is the key factor for the development of learning in the workplace. In Bulgaria, the two companies have completely different human resource management policies and structures. Usually, the human resource and development instruments are well developed in the subsidiaries of foreign multinationals (using transferred or locally adapted models) but absent in local companies. This is the situation in BG1 and BG2. In BG 1, a medium-sized company without formalised human resource management structures, human resource functions are fulfilled by general management. BG2 has a relatively well-developed human resource management department and policies. Human resource specialists are all recruited from the local area. Most have extensive work experience, but not necessarily diplomas in human resource management. They have a high degree of autonomy with respect to the human resource managers at headquarters. Human resource objectives are not strictly formulated in company documents. Some practices have been translated from the mother company, but initiatives were also developed at the level of BG2.

What can be seen is that in both cases, companies focus on work-based learning and develop internal capacities through training centres, trainers’ skills and so on. However, in BG1, there are no formalised policies, for example for career development; in BG2 this is more structured. In addition, a focus on organisation, leadership and soft skills seems particular to BG2 and to companies with more developed human resource management practices (often subsidiaries of multinationals), and contrasts with local companies like BG1, where the focus is on technical skills. A possible explanation is transfer of the headquarter’s organisational and learning culture.

In Spain, when the restructuring of the metal sector was tackled in the 1990s, the Basque Government made a commitment to promote a technologically advanced new metal sector: ‘Policies to upgrade the competitiveness of industry became the centrepiece of the Basque policy agenda, to which the rest of policies became subordinated’ (Porter et al., 2013: 7 quoted by López-Gereñu, 2018: 505). The policies subordinated to industrial competitiveness included, in chronological order, quality (ISO 9000 and later EFQM and Euskalit) and professional training, with the First Vocational Training Plan and its successors; the promotion of innovation and the creation of Innobasque; and internationalisation.

In the Basque cases, companies were committed to training. In the case of languages, internationalisation being a very important aspect, they offered language studies before workers started their working day. Employees were asked about their training interests. Employees with a particular interest in taking a specific course might find the company willing to finance part of it, though the training usually occurred outside working hours.

We’re very lucky. They offer us the course, they tell us “I think it could be good for you” and I decide. You always say yes because they are usually interesting. (ES1_ECW3_1_653)

Depending on whether the company is the one proposing it, it falls within your work schedule because it is interesting for the position. If it is not the company’s proposal but the worker’s but related to their job, they would support you financially but outside of hours. (ES1-ECW4_1_605).

The development of human resource management in the Spanish companies is related to the imperative to upgrade the sector and is linked to the different requirements and standards of high-profile manufacturing. In Bulgaria, practices are more situational, less developed in local companies, and stimulated in subsidiaries of foreign multinationals. In this sense, the Spanish case illustrates a more long-term approach to training, while in Bulgaria, policy seems to respond to urgent challenges.

How Organisational Agency Is Applied in Shaping Early Career Pathways

The Structuring of Early Career Pathways

We now turn to the structuration of early career pathways. For this purpose, we analysed a number of organisational and human resource management characteristics. In Bulgaria, all the employees of the two companies were engaged on permanent full-time contracts, with no part-timers, as is usual in Bulgarian companies in general and in this sector in particular. All newly recruited employees pass a six-month probation period and then, depending on performance, start working with permanent contracts. The companies under scrutiny have different career development pathways for workers. However, these are not formalised, existing only as informally shared expectations deduced from interviews, especially in BG 1. There are some examples of vertical or horizontal job mobility, but these are less common, and the majority of workers do the same job for years. In general, in both companies, the philosophy is that a person does not need any specific education for a new job, even in management; what is needed is to show the potential to cope with that job. Support for day-to-day informal workplace learning is provided mainly by team leaders.

Early career workers in BG1, were formerly guided only by experienced workers (mentors) during the time necessary to learn the basic functioning of the relevant machine(s). This process could take different periods of time—usually between 2 and 3 months, up to a maximum of 5–6 months. This coincided with the probation contract (6 months, according to Bulgarian labour legislation). In case of difficulties, the worker could speak first to the mentor or shift leader and then to the workshop manager or engineer-in-chief:

If there is a difficulty or problem, we turn to him. If it turns out he can’t decide either, we turn to the workshop manager or the engineer-in-chief. In general, the engineer-in-chief is the one most responsible for everything, and if there is a problem, it always comes to him to decide. (BG1_ECW1_1_28).

In the Spanish cases, the initial hiring involved a fixed-term contract for three years, with a further year of transition. Following this, an evaluation took place, conducted by two people in charge of monitoring the early career worker. Long-term contracts meant a permanent contract as a cooperative associate. The most important reward in structuring the early career pathways may be becoming a member of the cooperative and providing a secure and stable job virtually for life. In addition, if the cooperative achieves its goals, they share in the profits distributed among the members. They also have assemblies where members make decisions about the company and its social benefits.

Hiring is done with an eye to prospects for long-term employment and to an undefined sequence of jobs and roles within multi-skilled teams. This continuously enriched job roles and levels of responsibility; the early career pathway is thereby organised around the goal of achieving ‘partnership status’ as a key early career transition. Both Basque organisations embraced a strategy based on a stable, highly skilled and motivated, flexible workforce, capable of moving and growing with unknown technological challenges; employees enjoy particular membership rights and partake in the success of the cooperative.

For new job openings in ES1 and ES2, there was no hierarchy between the entry routes, but preference was given to internal promotion before the position was externally advertised. It was a strategic goal to provide workers with competitive knowledge and to develop talent within the company. Support for new entrants and their transition to full productive work or to longer, well-structured induction was quick, supervised by a person responsible for its follow-up. The companies implemented collective agreement for the metal sector.

Comparison of the Spanish and Bulgarian cases shows that in both cases, long-term engagement of employees is preferred. However, in Spain, the learning pathways and curricula were well established and formalised, while in Bulgaria, formalised training is just emerging and covers only a small proportion of early career workers, though a trend towards higher levels of formalisation can be observed. The Spanish companies focus on multiskilling from the outset, while horizontal job transitions were rare in the Bulgarian companies.

The Impact of Organisations’ Decisions on Early Career Workers’ Agency to Learn in the Workplace and Beyond

The organisational arrangements described above impact in a different way on the interplay between the external and the internal provision of skills.

Bulgarian early career workers have been trained mainly on-the-job-training schemes through the post-communist period (previously very structured training was in place). During the last few years, the vocational education and training system has been poorly connected with the real needs of companies (Kirov, 2015), which impacted on the companies’ willingness to invest in internal skills acquisition. This had been reinforced by both companies being located in rural areas where vocational education and training had been interrupted (BG1) or diminished significantly (BG2). However, in BG1 all efforts have been focused on internal processes. In BG2 investment was also external, supporting the country’s emerging dual vocational education and training. BG2 is one of the pioneers in the establishment of dual apprenticeships in Bulgaria, having launched this initiative in the district together with three other metal sector companies. This pilot dual-apprenticeship initiative was supported by the Austrian Chamber of Commerce (Wirtschaftskammer).Footnote 5 Thanks to this programme, BG2 now had one of the first (and soon-to-graduate) classes of work-based learners:

But these two classes are actually with us, the first one graduates this year. When it became possible, and it was accepted that such training through work can exist, we already had a class in fact. After which the second class came and after that we were able to find children, not only we, but with the support of the school of course, children who would enter into the dual form of training. (BG2_M1_1_181).

In both companies, establishing training centres had been achieved through their own investment. However, they also benefitted from external support schemes. For example, in 2017 BG1 was involved in a European Structural Fund project for training and recruitment of vulnerable youth (12 people in all). According to the rules of this Youth Guarantee project, at least six people were supposed to be hired for at least one year after the completion of the project; the project was completed successfully.

In Spain, there were good relationships between the companies and the vocational training centres (accredited by the company itself). The company requests the number of assemblers needed each year; its human resource managers evaluate the people and choose the most suitable. The corporation also has a university offering substantial training for professionals, nourished by relationships between centres, companies and in-company training. Training aims at continuous learning for workers and when financed by companies themselves is more effective.

When early career workers arrive at the companies, they have an ‘onboarding’ process which includes learning what a cooperative is, how it is organised and what the functions of each body are. ES1 has an in-house vocational training school to train young workers, as well as specific language training and tailor-made courses for specific projects. ES2 selects expert workers to mentor and train new workers and prepare manuals. In addition, there are courses and other specific training activities; both companies have human resource departments to collect and provide information about available training for all workers.

Both companies support pathways for early career workers in a fairly structured way, in the form of actions such as rotation, internal training, mobility and progressive delegation of responsibility. Company support for early career workers’ pathway makes it easier for them to become aware of the learning opportunities available in the workplace and has a positive effect on the young workers’ agency.

The comparison of the Bulgarian and Spanish cases allows us to identify a number of differences. The training structure is more formalised in the Spanish cases, while still in the making in Bulgaria. The training centres are accredited by the Spanish companies; while Bulgarian companies have started to use some external support schemes, the bulk of their investment in training is internal.

How Organisational Agency in Workplace Design and Career Structuration Interacts with Individual Agency to Learn in the Workplace

In the previous two sections, we examined how organisational agency has shaped the structuration of workplace learning opportunities in practice and how early-career pathways are shaped. In this section, the focus is on individual agency or, in other words, how workers in the same firm behave differently or in the same way. Here our inputs come from the learning-biography vignettes.

In Bulgaria, the majority of the workplaces were characterised by monotonous routine tasks and poor learning potential; over-qualification among the respondents was common, being accepted as a trade-off for secure long-term employment opportunities and secure earnings.

In the Bulgarian metals sector, a pattern was observed of individuals’ learning benefitting from—sometimes only small—changes in work tasks, such as moving from a simple to a more advanced machine, or from taking on additional work as a trainer for in-house training programmes.

Some examples from the Bulgarian cases illustrate the trajectories of early career workers with previous experience from different sectors and focus on the on-the-job-training within the company. Two representative trajectory cases are illustrated here.

The first is Kalin (30–34 years old), who had come from the construction sector. He had been working for six years at BG1. When he started work as a mechanic, he had an instructor: he was attached to a supervisor who guided him in purely practical tasks. The company at that time did not offer theoretical training. With every new position he held, Kalin received only practical training:

I first started with the mechanics, after that with the digital milling machine, but with ordinary attachment. It is digital too, but with manual setting, it has no measuring appliances within the machines like these ones. After that, after two-three years, they transferred me to the newer machines and now, since last year, to one of the newest. (BG1_ECW2_1_55).

However, Kalin acknowledged that the theoretical training his more recently hired colleagues received helped them to adapt more easily to the production process.

For them it is sort of easier this way, getting more advanced in the work, and not... Theoretically and gradually, to advance in the work and not being required to start production at once. Everything is sort of gradual, right—first in theory and then in practice. It’s not so hurried. (BG1_ECW2_1_233).

The second trajectory examined here is Snejana’s. Aged 30–34, she worked as a lathe operator in a milling machine unit of the same company. She pursued a higher education and received a bachelor’s diploma in Pedagogy of Mathematics and Informatics. After taking parental leave, Snejana received a permanent work contract after working for the company for two years. When she started working for the company, she passed a course of training, which was both theoretical and practical:

the engineers, the head of the workshop also, the people in higher positions than us, were reading something like lectures to us, in order to familiarie us with the measuring equipment, the kinds of materials, the kinds of instruments’ (BG1_ECW1_100); ‘For two months I was with another person on a machine, after that they let me work independently with a machine’ (BG1_ECW1_1_113).

At the time of the field work, Snejana was fulfilling the role of a trainer, expanding her job role by working not only in the milling machine unit but also at the company’s training centre, contributing to the practical training of new employees.

These examples illustrate how individuals benefitted from the learning opportunities to advance in their careers, being transferred to more complex machines or expanding their job profile as a trainer—despite, particularly in the case of Snejana, having exchanged her higher education qualification and career prospects in upper secondary education to become a semi-skilled worker.

However, other individual trajectories suggest that some early career workers have not been changing their positions and have only acquired initial on-the-job training. There are cases of relatively intense learning in a poor learning environment, such as Rositsa’s. She has a bachelor’s degree in culture studies but has never worked in this field and spent years in different jobs, such as retail. In BG1, she entered a routine position, but following a training course was promoted to a milling machine operator position; as this involved more non-routine activities, she considered it a step up in the hierarchy (see Enliven, 2020b, p. 82).

In Spain, employees described their work as a challenge in which they were continually learning. They found it stimulating because each project and machine meant they had to put different skills into play: autonomy and teamwork, problem-solving, systemic and logical analysis and team leadership and management. For example, the company’s projects in different countries meant it was sometimes necessary for early career workers to go abroad to assemble the machines. John had to go several times, finding his learning much greater as a result, because he had to solve the difficulties of assembly without the support from his group:

This is nice because every day there are problems, new problems. In that sense it’s the best this job has. You’re satisfied because you’re every day with little problems, and telling the others... how does this work? This does suit me. (ES2_ECW7_1_136).

Oscar assumed greater responsibility and autonomy when he was in charge of setting up a company delegation in another country:

In the beginning change was challenging because there I had quite defined what I had to do on a day-to-day basis. I had my projects, my plans, my resources... I arrived at work every day and knew what I had to do. Here, everything is new and what you do is welcome. I haven’t had a clear guideline ‘today you have to do this, for next week, this.’ (ES1_ECW3_ 2_132)

In Spain, unlike Bulgaria, the Basque companies encouraged workers to develop their full potential. In both ES1 and ES2, there was no separation of routine from non-routine learning. Employees had support structures for non-formal learning, such as individual training plans for new recruits, technical courses and language training in the workplace, an assembly school (in ES1) and support (in ES2) from a mentor who documented the processes. Supported by the team, by a mentor and by the organisation itself, they also had many opportunities for informal learning from the challenges of unexpected situations. They also rotated through different positions as part of their learning process, giving them the opportunity to learn about the different processes that are part of their work.

Workers who have the attitude and aptitude, highly valued by the company, would continue to be promoted: ‘My goal before was to get to know the company, the world of work, to learn. Now it has to do with responsibility, develop yourself, to make a contribution.’ (ES2_ECW8_1_ 1124).

This exploration of how individual agency is applied in the four cases shows that the Spanish early career workers were aware that they were learning formally, non-formally and informally, and that they received support from the company, valuing this highly. They described their learning as linked to their day-to-day experience and supported by colleagues and supervisors in non-routine jobs.

For example Martin (20–24), an assembler who has been working full time for a year and a half, expresses his trajectory in the following way:

I think I feel competent already (ES1_ECW1_2 _152). At work, after a year, those on top see me in a different way. I also see myself in a different way. Your attitude changes, because at the beginning, you feel inhibited... but now, if you have a problem, you know how to solve it. I feel more relaxed. Gradually they are giving you more responsibilities. Yes. What happens is that sometimes they give responsibilities very easily, but... now I feel like one more worker. I think I used to be like an assistant, now I feel I am one more - ‘tomorrow it’s Martin’s turn’ (ES1_ECW1_2 _158).

Oscar, on the other hand, was committed to his responsibilities and valued the trust the company placed in him. This enabled him to learn and become more and more competent. About his duties in China, he said: ‘But well, they expected that from me: we will send him, who has potential, there and let’s see what he does’ (interview 2) (ES1_ECW3_2_157).

In the Bulgarian context, the agency of individual early career workers is applied in the context of poor learning potential. As shown, those workplaces also provide conditions for active agency, even if, generally, most individuals are satisfied to accept the routine work for the sake of decent pay or a kind of late Fordist wage compromise (Boyer & Durand, 2016).

In Spain, the agency of individual early career workers was applied in rich learning environments. However, despite the importance of stability and opportunities for promotion, the challenges posed by innovation, international mobility, the possibility of changing jobs and professional categories allow us to extract from the interviews that around the age of 30 (a key moment for vital decisions), workers are often faced with challenges in reconciling well-being at work with other areas of personal and social life.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have explored how organisational and individual agency provide space for informal workplace learning, and the outcomes of this learning for early career workers, in the Spanish and Bulgarian metal sector.

Regarding the first dimension, organisational agency, organisational patterns and complexity of production support intensive workplace learning in Spain’s Basque country. Learning is provided at different stages of career development, both in technical knowledge and soft skills; the companies examined provide turnkey solutions, with workers being involved in interactions with client personnel during the installation and maintenance of individualised technological projects. Company policy evolved in the context of the region’s developing vocational education and training system, combined with strong learning structures in or around the companies. In Bulgaria, metal sector companies act largely as subcontractors, producing only particular items and components for the contractors. For a long time, informal workplace-based learning consisted only or mainly of on-the-job training for fixed jobs. Recent production upgrade and lack of previously trained personnel, however, stimulated the emergence of broader and more formalised training, covering not only basic technical skills but also theory and some elements of soft skills. In this situation, early career workers with potential have had chances to move to more complex machines, to experience horizontal mobility or even vertical promotion to first-level managerial responsibilities.

Individual agency in the Basque cases is expressed in the way employees take advantage of the rich formal, non-formal and informal learning opportunities offered by the companies. Early career workers are motivated and want to stay in their company. Those who are already partners enjoy autonomy and responsibility; others aim to become partners. Individual agency in the Bulgarian cases opened some limited opportunities for further training and career development, depending on volunteering by early career workers (e.g. such as for those in BG1 who wanted to take theoretical training), but this was largely shaped by the hierarchy and occurred without explicit rules. In the Basque country cases, companies offered opportunities for promotion and workers valued this, acting with initiative and commitment.

This chapter has also addressed work-based learning in countries that have been less well-covered in the literature: Bulgaria (representing the Eastern European or post-communist model, as discussed in Delteil and Kirov (2016)) and Spain (representing the South-European model). The approach adopted, using a qualitative methodology, has allowed us to go beyond the analysis of relatively static macro-data about lifelong learning in the sector and to build an interpretation of the developments observed.

Notes

- 1.

This chapter covers the manufacture of metal products, except machinery and equipment, together with the manufacture of machinery and equipment.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

CNC (computer numerical control) machining is a manufacturing process in which pre-programmed computer software dictates the movement of factory tools and machinery.

- 5.

References

Alessandrini, M., Celotti, P., Gramillano, A., & Lilla, M. (2017). The Future of Industry in Europe. European Committee of the Regions.

Bakaikoa, B., Begiristain, A., Errasti, A., & Goikoetxea, G. (2004). Redes e innovación cooperativa. CIRIEC-España, revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa, 49, 263–294.

Boyadjieva, P., Milenkova, V., Gornev, G., Petkova, K., & Nenkova, D. (2012). The Lifelong Learning Hybrid: Policy, Institutions and Learners in Lifelong Learning in Bulgaria. Iztok-Zapad.

Boyer, R., & Durand, J. P. (2016). After Fordism. Springer.

Delteil, V., & Kirov, V. N. (Eds.). (2016). Labour and Social Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe: Europeanization and Beyond. Routledge.

ENLIVEN Project Consortium. (2020a). Cross-sector and cross-country comparative report on organisational structuration of early careers - comparative report and country studies in three sectors. Enliven project report D5.1. Retrieved from: https://h2020enliven.files.wordpress.com/2021/08/enliven-d5.1_final.pdf

ENLIVEN Project Consortium. (2020b). Agency in workplace learning of young adults in intersection with their evolving life structure. Deliverable 6.1. Enliven project report. Retrieved from: https://h2020enliven.files.wordpress.com/2021/07/enliven-d6.1_final-2.pdf

Evans, K. (2007). Concepts of bounded agency in education, work, and the personal lives of young adults. International Journal of Psychology, 42(2), 85–93.

Gallie, D. (2007). Employment Regimes and the Quality of Work. Oxford University Press.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The Governance of Global Value Chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104.

Kasmir, S. (1999). El Mito de Mondragón. Txalaparta.

Kirov, V. (2015). The Link Between the Labour Market and the Vocational Education and Training in Bulgaria. In R. Stoilova, K. Petkova, & S. Koleva (Eds.), Znanieto kato zennost, poznanieto kato prizvanie (pp. 209–222). East-West Publishing House. (in Bulgarian).

Kirov, V. (2018). Bulgaria: Metal Sector. Unpublished Enliven Project Report. Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

Landabaso, M., Mouton, B., & Miedzinski, M. (2003). Regional innovation strategies; a tool to improve social capital and institutional efficiency? Lessons from the European Regional Development Fund innovative actions. Regional Studies Association conference: Reinventing regions in a global economy, Pisa, Italy.

López-Gereñu, N. (2018). Exploring VET Policy Making: The Policy Borrowing and Learning Nexus in Relation to Plurinational States - the Basque Case. Journal of Education and Work, 31(5–6), 503–518.

Martínez, A. (2009). Innovación y Cooperativas. Boletín de la Asociación Internacional de Derecho Cooperativo, Núm. 43/2009 (pp. 135–157). Deusto.

Porter, M., Ketels, C. H. M., & Valdaliso, J. M. (2013). The Basque Country: Strategy for Economic Development. Harvard Business School Publishing.

Sapir, A. (2006). Globalization and the Reform of European Social Models. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(2), 369–390.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kirov, V., Estevez-Gutierrez, A.I., Elexpuru-Albizuri, I., Díez, F., Villardón-Gallego, L., Aurrekoetxea-Casaus, M. (2023). Organisational and Individual Agency in Workplace Learning in the European Metal Sector. In: Holford, J., Boyadjieva, P., Clancy, S., Hefler, G., Studená, I. (eds) Lifelong Learning, Young Adults and the Challenges of Disadvantage in Europe. Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14108-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14109-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)