Abstract

The period during which young people are financially and residentially dependent on their parents is lengthening and extending into adulthood. This has created an in-between period of “emerging adulthood” where young people are legal adults but without the full responsibilities and autonomy of independent adults. There is considerable debate over whether emerging adulthood represents a new developmental phase in which young people invest in schooling, work experiences, and life skills to increase their later lifetime chances of success or a reflection of poor economic opportunities and high living costs that constrain young people into dependence. In this chapter we examine the incidence of emerging adulthood and the characteristics and behaviours of emerging adults, investigating data from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey. We find that a majority of young Australians who are 22 years old or younger are residentially and financial dependent on their parents and thus, emerging adults. We also find that a substantial minority of 23- to 25-year-olds meet this definition and that the proportion of young people who are emerging adults has grown over time. Emerging adults have autonomy in some spheres of their lives but not others. Most emerging adults are enrolled in school. Although most also work, they often do so through casual jobs and with low earnings. Young people with high-income parents receive co-residential and financial support longer than young people with low-income parents. Similarly, non-Indigenous young people and young people from two-parent families receive support for longer than Indigenous Australians or young people from single-parent backgrounds. The evidence strongly supports distinguishing emerging adulthood from other stages in the life course.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Young people’s transitions to adult roles, including completing school, entering full-time work, leaving their parents’ home, marrying, and becoming parents, are occurring at older ages and more heterogeneously in Australia and other developed countries (see, e.g., Cobb-Clark, 2008; Elzinga & Liefbroer, 2007; Furstenberg, 2010; Settersten & Ray, 2010). Whereas many of these transitions occurred at or near the time of reaching legal adulthood in the 1960s and 1970s, they often occur in people’s mid- and late-20s—or later—today. This has created a new period in the life course of “emerging adulthood” in which young people are legal adults but also dependent on their families and not fully autonomous. As a life course period, emerging adulthood entails developmental and growth opportunities, especially for young people who engage in schooling, training, work experiences, developing relationship skills, and other activities. It is also shaped by a host of contexts, including family environment, economic opportunities, institutional supports, and social norms.

This chapter takes a life course perspective to review studies that have examined emerging adulthood and to examine empirically the patterns and conditions of emerging adulthood in Australia. As described in Chap. 2, the life course perspective is a multidisciplinary conceptualization of the sequence of socially meaningful transitions in a person’s life that places those transitions in overlapping contexts of family, community, and society. The perspective extends theories of development to a person’s entire lifetime and also incorporates ecological theories. In addition to these theoretical considerations, the chapter empirically analyses 2001–2018 data from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, which conducts annual interviews of people aged 15 years and older in Australian households and follows those people over time, including when they leave their original households. As with many previous analyses, the chapter documents the numbers of young people who can be categorized as emerging adults, how these numbers have changed over time, and how they differ across groups. More distinctively, however, the chapter examines the conditions of emerging adulthood—that is, how this stage is lived.

Emerging Adulthood

Defining Emerging Adulthood

The introduction of the term “emerging adulthood” is widely attributed to Arnett (2000), who used it to describe a distinct and historically new developmental period that extended from people’s late teens to their early 20s. Arnett conceptualized emerging adulthood as being bracketed by and distinct from people’s adolescence and early adulthood. He emphasized the amount of choice and volition during this period regarding eventual adult roles and characterized it developmentally in terms of identity formation, especially in the areas of romantic relationships, career, and “worldviews.” Others (see, e.g., Côté, 2014, Côté & Bynner, 2008), while acknowledging the growing prevalence and in-betweenness of emerging adulthood, have sharply criticized Arnett’s developmental framing. Far from a period of choice and volition, they emphasise how emerging adulthood likely reflects constraints from reduced economic opportunities, high housing costs, and inadequate social supports. They further see the developmental framing as dangerous as it distracts society and policymakers from addressing young people’s growing structural disadvantages. The life course perspective helps to reconcile both approaches by positing that developmental and structural explanations must be considered together, rather than exclusively. Of course, in addition to researchers who have used the term “emerging adulthood” formally, many others have used it more loosely to categorize young adults.

Just as there is debate on the definition and meaning of emerging adulthood, there is debate on when this period ends and early adulthood begins. Consistent with the notion of volition, Arnett’s (2000) initial formulation saw the end in terms of subjective elements of young people feeling responsibility over life domains and having the ability to make independent decisions. More recently, Arnett (2007) has described the end of emerging adulthood in terms of undertaking, though possibly not completing, the major adult transitions of finishing school, starting work, living independently, partnering, and parenting. Benson and Furstenberg (2006) directly asked young Americans about whether they considered themselves to be adults. In support of Arnett’s demarcation, they found that adult identity was strongly tied to living independently and becoming a parent but was only moderately tied to completing schooling or working. Interestingly, they also found that reversals in transitions, such as having to move back in with parents, reduced young people’s identification as adults.

In this chapter, we will use the term emerging adulthood to describe people who have reached the legal age of adulthood (18 years in Australia) but who remain residentially and financially dependent on their families and thus have not taken on all the responsibilities or gained the full autonomy of adulthood. Our definition differs from some others by demarking the end of the period in terms of the behavioural outcomes of attaining residential and financial independence, which occur at different ages for different people. Because some people attain both forms of independence by age 18, our definition also implies that emerging adulthood is not universally experienced. Our analyses examine partnering and parenting, but we do not include them in our definition because recent cohorts of young Australians tend to experience these outcomes many years after achieving residential and financial independence.

Characteristics Associated with Receiving Support

Logically, parents’ economic resources will affect their ability to support their young adult children. Empirical research has found support for this conjecture across many different measures of resources. Specifically, coresidential and financial support tend to be higher for parents with greater financial wealth (Schoeni, 1997) and higher socioeconomic status (Angelini et al., 2020) and lower for parents with long histories of welfare receipt (Cobb-Clark & Gørgens, 2014), histories of poverty (Kendig et al., 2014), and financial stress (Cobb-Clark & Ribar, 2012). Having more children also limits parents’ effective resources and has been found to reduce parental support (Schoeni, 1997). In addition to these characteristics, Cobb-Clark and Ribar (2012) have found that conflict between parents can prompt young adults to leave home sooner.

Characteristics of the child who might receive support are also important. To the extent that parents’ motivation for providing support and children’s willingness to accept support are guided by concerns for children’s wellbeing, exchanges of support will rise with children’s needs. Consistent with this, empirical evidence shows that material support increases with different measures of children’s needs (Hartnett et al., 2013; Schoeni, 1997) and falls as children age (Angelini et al., 2020; Hartnett et al., 2013). Within Australia, norms for supporting adult children also increase with children’s needs and fall with children’s ages (Drake et al., 2018). Co-residential and financial support have also been found to be lower for children with emotional distress (Sandberg-Thoma et al., 2015). Support falls as young adult children identify more strongly as adults (Hartnett et al., 2013), and it is lower for daughters than sons (Cobb-Clark, 2008). More closely examining gender differences, Wong (2018) found that young men who experienced negative life shocks, such as the illness of a close friend, tended to remain at home longer while young women left home sooner. Wong also found that heavy drinking contributes to young men and women leaving home earlier and that an early initiation of smoking contributes to young women leaving earlier.

Support may also be affected by characteristics of the parent-child dyad, especially the relationship between the parents and their young adult children. However, the evidence regarding the effects of parent-child relationships on support is mixed. Cobb-Clark and Ribar (2012) have found that unsatisfactory parent-child relationships are associated with earlier nest-leaving. However, Gillespie (2020) finds that close parent-child relationships are positively associated with leaving home, especially for the relationships between mothers and daughters. The conflicting findings may be explained by relationship quality and support mutually affecting each other. For example, Johnson (2013) has found that financial assistance at one age is associated with children being closer to parents at a later age.

Effects of Support

If emerging adulthood serves a developmental purpose, we would expect to see benefits associated with it. The largest advantages appear to be in terms of completing more schooling (Swartz et al., 2017; Wong, 2018, see also the review by Cobb-Clark, 2008). However, evidence on the associations of emerging adulthood with other outcomes is equivocal. Fingerman et al. (2015) found that intense support from parents increased young adult offsprings’ sense of defined goals and life satisfaction, and as mentioned, Johnson (2013) uncovered a positive association between parent support and subsequent close parent-child relationships. However, Johnson also found that parental support increased young adults’ depressive symptoms, and Mortimer et al. (2016) found that support reduced young adults’ self-efficacy. In a more developmentally focused study, Roisman et al. (2004) found that three developmental tasks that were salient to adolescence—building friendship, academic, and conduct skills—were predictive of subsequent adult success. However, two tasks identified by Arnett (2000) for emerging adulthood—building work and romantic skills—were not consequential for later adult success.

What Emerging Adults Do

Although many studies have been conducted of who emerging adults are, how long emerging adulthood lasts, and whether emerging adulthood is consequential for later outcomes, Furstenberg (2010) and others have noted that much less research has considered emerging adulthood as it is lived. The authors have contributed to several of the available studies. Wong (2018) used the HILDA Survey to examine smoking and heavy drinking among co-resident emerging adults. Botha et al. (2020) used the HILDA Survey to examine how financial autonomy grew and developed over the course of emerging adulthood for men but not women. Ribar (2015) also used these data and found that emerging adults suffered fewer financial hardships than newly independent adults. In addition to these studies, Hartmann and Swartz (2007) interviewed emerging adults to document their understandings of their roles. They found that emerging adults see themselves positively in a new and distinct role that is shaped by dynamism.

Description of the Analysis Sample from the HILDA Survey

Our empirical analyses draw data from the first 18 waves of the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey. The HILDA Survey is a large national longitudinal survey that began with 19,914 people in 7682 Australian households in 2001 and has subsequently followed those people and their families in annual interviews. Each wave asks every household member aged 15 years and older about personal and household economic conditions, demographic circumstances, life changes, and other characteristics through multiple instruments, including face-to-face interviews and self-completed questionnaires. Importantly, the HILDA Survey continues to follow members and children of original sample households even after they leave their initial homes, allowing us to examine young people while and after they co-reside with their families. Attrition has been modest; by the 18th wave, 62% of the original survey respondents completed interviews (Summerfield et al., 2019). We extracted the HILDA data with the PanelWhiz add-on for Stata (Hahn & Haisken-DeNew, 2013).

For our analyses, we select annual observations for 11,660 HILDA Survey respondents who were ever observed when they were 15–25 years old. Because of the longitudinal structure of the survey, the sample includes multiple annual observations for most of the respondents. Some of our analyses include observations for adolescents, aged 15–17 years, and some are restricted to young adults, aged 18–25 years. Although the HILDA Survey provides weights that address sampling issues and attrition for the general sample, we only conduct unweighted analyses because we are using a selective sample.

As with the analysis by Cobb-Clark and Gørgens (2014), we consider two forms of support that parents might provide. The first is co-residence with one or both of the young person’s parents, which is measured at the time of the HILDA Survey interview. The second is an indicator for whether the young person received a direct financial transfer (of any amount) from his or her parents. Most of our analyses distinguish among young people who receive both co-residential and financial support, receive only co-residential support, receive only financial support, or receive neither type of support. Our analyses label young people who receive one or both types of support as “emerging adults” and those who do not receive either type of support as being “independent.” In several analyses, we further distinguish between young adults who have been independent for three or fewer consecutive years and those who have been independent for longer, as previous research by Ribar (2015) shows that young people’s conditions change with the duration of independence. We also examine young people who “boomerang” back into co-residence with parents after living apart for at least one wave of the HILDA Survey.

Our analyses consider many other measures from the HILDA Survey of conditions and characteristics of the young people, which we explain within each analysis.

Parental Support in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood

We begin our empirical analysis by examining the percentages of Australian adolescents and young adults who co-reside with their parents, receive financial transfers, or both. Figure 8.1 shows these percentages at each age from ages 15 to 25, using all the data from the HILDA Survey from 2001 through 2018. We consider young adults who co-reside with or receive transfers from their parents to be emerging adults, so the graph shows the extent of emerging adulthood at each age.

The estimates indicate that at age 15 almost all (98% of) young Australians co-reside with their parents. Co-residence falls with age but remains very prevalent through adolescence. At age 17, 90% of young people are co-residing with parents. The incidence of co-residence falls more noticeably starting at age 18. At age 21, the incidence of co-residence drops below 50%, and by age 25, only 21% live with their parents.

The incidence of financial transfers is much lower but follows the same age pattern. At age 15, just under half of young Australians are receiving transfers from their parents. By age 18, about a third are receiving transfers, and by age 25, only 9% are receiving transfers. In adolescence, transfers are mostly received in conjunction with co-residence. By age 22, transfers are slightly more likely to be received while living independently than while co-residing.

The estimates also reveal the heterogeneity in coresidential and financial support. For example, at ages 18 and 19, most young people are receiving some type of support from their families, but substantial fractions are not and thus effectively skip any period of emerging adulthood. By age 22, nearly equal proportions of young people are and are not receiving support, and by age 25, most young people are independent, but a substantial fraction (27%) are not. Consistent with the findings for other countries by Elzinga and Liefbroer (2007) and others that transitions to adulthood are heterogeneous, the estimates indicate that there is no single, uniform path through emerging adulthood in Australia.

We next consider whether and how young Australians’ receipt of coresidential and financial support changed from 2001 to 2018. Figure 8.2 shows the year-by-year percentages of people aged 15–17 years old (left panels), 18–21 years old (centre panels), and 22–25 years old (right panels) in the HILDA Survey who co-reside with their parents (top panels) or receive financial support from their parents (bottom panels). The incidence of co-residence among adolescents (people 15–17 years old) has remained relatively constant within a range of 92–95% over the period. In contrast, co-residence among 18- to 21-year-olds fell modestly from 2001 to 2006 and then generally grew from 2006 to 2018. On net, co-residence for 18- to 21-year-olds increased over the period. Co-residence among 22- to 25-year-olds was relatively constant from 2001 to 2010 but grew after 2010 and increased on net over the entire period. Overall, co-residential support for young Australians has increased since 2010, especially among 22- to 25-year-olds.

The patterns for financial support are different, with the prevalence increasing for adolescents and both groups of young adults and with the increases being larger for adolescents and 18- to 21-year-olds. There was no discernible trend for any of the groups in the early 2000s but a strong upward trend since 2009 and an upward trend on net over the entire period. When we consider co-residential and financial support together, it is clear that the proportion of 18- to 25-year-old Australians who are emerging adults has increased.

Characteristics, Activities, and Resources of Emerging Adults

The preceding analyses indicate that young people differ considerably in whether and when they co-reside with parents and receive financial support. As we will show in the next analyses, the heterogeneity in co-residence and financial support extends beyond young people’s ages and occurs across other characteristics. Additionally, we consider how young people’s activities and resources differ conditional on the dependence or independence from parents. For each of these analyses, we consider cross-tabulated results, which reveal associations between young people’s dependence and other outcomes but not causal relationships.

Characteristics and Activities

We consider the characteristics and activities that are associated with emerging adulthood in Table 8.1. Table 8.1 reports means of 18- to 25-year-old Australians’ characteristics and activities conditional on whether they receive both co-residential and financial support from parents (column 1), receive only co-residential support (column 2), receive only financial support (column 3), have been independent for 3 years or less (column 4), or have been independent for more than 3 years (column 5). It also reports the means for the entire sample of young adults (column 6). The first three columns indicate characteristics and activities of emerging adults, while the next two columns examine independent adults.

The top panel of Table 8.1 reports conditional averages of several characteristics. The first row reports the young people’s average ages and, consistent with Fig. 8.2, indicates that the receipt of support is more likely to occur among younger rather than older people. The next rows report averages for other demographic characteristics, which can be compared against the overall sample average in the rightmost column. In general, women are more likely than men to be independent of parents; however, women are also more likely to only receive financial support from their parents. Young Indigenous Australians are more likely than other young Australians to be independent of parents, while young people from migrant families are less likely to be independent. Young people from single-parent families and in rural areas are more likely to be living with their families but less likely to only be receiving financial support than those from other families. High school graduates are less likely to be independent of parents, while college graduates are more likely to be independent.

The bottom panel of Table 8.1 reports the average levels of several activities and conditions of young people. Two-thirds of young Australians who are co-residing and receiving financial support are studying, while very few of those who are independent are still studying. Employment is common among all young Australians and especially prevalent among those who are independent. Although most emerging adults work, the majority of those jobs are on casual contracts, and their average earnings tend to be low. Thus, many emerging adults have transitioned to work but not to permanent, well-paying jobs. Household-level rent is lower once living independently—independent young adults may live in smaller/lower-cost accommodation than the parental home. However, among those living independently, household rents are slightly higher for young people receiving financial support, which may assist with renting better housing. Rates of marriage and partnership and of parenthood are very low for young Australians aged between 18 and 25, but the rates are proportionally much higher among those who are independent and those who live apart from parents but receive financial support from them.

Emerging adulthood is conceptualised to involve autonomy and responsibility in some life domains but not others, and the estimates from Table 8.1 provide strong evidence for this. One potential area of autonomy is engaging in risky health behaviours. Rates of consuming five or more standard alcoholic drinks in a day are higher among emerging adults than young independent adults; however, rates of smoking are lower among emerging adults. Co-resident emerging adults also report moderately high levels of autonomy over their social lives and work choices, but young adults who live independent of parents report even more autonomy. In contrast to these domains with moderately high autonomy, co-resident emerging adults report little responsibility or autonomy for day-to-day spending in their households, large purchases, or financial matters.

Wealth, Debt, and Financial Wellbeing

Table 8.1 indicates that most emerging adults work and receive independent resources from earnings. In addition to these flows of resources, we can examine other aspects of their financial lives, including their bank account holdings, debts, superannuation, and financial wellbeing. Table 8.2 reports statistics on these outcomes. It is organised the same way as Table 8.1 but reports statistics for financial characteristics. Because many financial outcomes have skewed distributions (many low values but a few very high values), the table lists averages (the first figure in each table cell) and medians (the second value in each cell, listed in parentheses) of the outcomes.

For the period that we study, the average individual bank account balance for Australians aged 18–25 years old was just under $4800, but the median balance was $900, indicating that the distribution is very skewed towards low balances. The balances also provide little in the way of a savings buffer—the median balance of $900 amounts to less than a week and a half of young workers’ average earnings. Young people who are receiving financial support and those who are independent have smaller average account balances, while those who are co-residing with parents but not receiving financial support have larger average balances. Young people who are independent of their parents also have lower median balances. The results suggest that co-residence helps emerging adults build savings, especially when we consider the younger average ages and lower earnings of co-resident young adults. The higher balances among co-residing young people who do not receive financial support further suggest that these transfers may be conditioned on need.

Few young Australians held joint bank accounts. The median balance for all 18- to 25-year-olds and for each of the subgroups was zero. However, average balances were higher for those who were independent of their parents, which is consistent with their higher rates of partnership and marriage. Similarly, few young Australians had credit card balances, and the average balances were low. In contrast, average Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) and Higher Education Loan Programme (HELP) balances and other debt balances are higher, reflecting the high rates of study particularly among emerging adults, though median balances are zero.

Young adults hold modest superannuation balances. Balances are very low for emerging adults who are both co-residing with and receiving financial support from parents, and balances are moderate for young adults who are living independently. These results, too, are consistent with independent adults being older, earning more, and having longer work histories.

When we consider other measures of financial wellbeing, we see that most young people would struggle to raise funds in an emergency, though emerging adults report slightly less difficulty than young independent adults. Nearly a quarter of young co-resident adults and 37–51% of non-coresident adults also report at least one experience of material deprivation as a reflection of financial hardship, such as not being able to pay a utility bill, in the previous year. Despite these negative indicators of financial wellbeing, young Australians report moderately high average satisfaction with their financial situations. The findings for financial wellbeing mirror those reported by Ribar (2015).

Differential Experiences in Becoming Independent

Timing of Independence

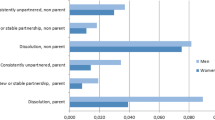

The longitudinal data from the HILDA Survey allow us to investigate more closely the timing of young people’s transition from emerging adulthood to independence from parents. For this analysis, we select observations from our general sample of 18- to 25-year-olds for young people who are continuously interviewed from age 15 on. We follow them until the first interview at which they are neither co-residing nor receiving financial support from parents, age 25, or they attrit from the sample. For people who are observed to transition to independence, we can measure the duration to this event. For people who reach age 25 or attrit from the sample without transitioning, we know that the transition occurred after the last time we observed them. To address the partial loss of information from the people whose transitions are not observed, we estimate Kaplan-Meier, or life-table, hazard probabilities of transitioning to independence and use these hazard probabilities to estimate the median age of transitioning (formally, the point at which the cumulative hazard function reaches 50%). Table 8.3 reports these median ages for the entire sample and for subgroups defined in terms of household income, parents’ household structure, indigenous background, and migrant background; Fig. 8.3 presents the corresponding probabilities of “surviving” (that is, continuing to receive parental support) across the age profile.

Consistent with the characteristics of emerging adults described previously, the median timing to independence also differs by economic resources and demographics. Overall, 50% of emerging adults become independent of co-resident and financial supports by age 22.2. When considering household income as ranked at age 15, emerging adults from more affluent households tended to establish independence at older ages, indicating that those from an advantaged or well-resourced household receive parental support for a longer period of time. A similar pattern emerges for both household structure and indigenous status, where emerging adults from single-parent households or from an indigenous background also tend to become independent sooner. This is especially pronounced for Indigenous Australians, where the median age of independence is 19.1. Conversely, emerging adults with a migrant background tend to receive parental support for longer, with a median independent age of 23.7.

Prevalence of Returning Home

We use a similar event-history methodology to examine the probability that young people who transition to independence later “boomerang” and return home. For this analysis, we select young people in the HILDA Survey who are observed to transition to independence. We then follow them until they return home, reach age 30, or attrit from the HILDA Survey. We use the Kaplan-Meier approach to calculate the cumulative hazard of the years until they return home, presenting the information in Table 8.4. As with the previous analysis, the cumulative hazard accounts for the partial loss of information from people who reach age 30 or attrit from the sample without being observed to make a transition. Persons who return home within their first year of independence cannot be distinguished in the HILDA survey from others who continued to receive parental support; there are consequently no “boomerang” cases in the first year.

The cumulative hazard of returning home is initially quite steep. Over 9% of young adults return to their parents’ home in the year after becoming independent. This indicates that for some young Australians—intentionally or otherwise—independence is a brief or temporary arrangement, and parental support is accessed soon afterwards. Although the cumulative hazard rate continues to increase in subsequent years it also flattens out substantially; young adults who have been independent for four or more years have likely left the parental home for the last time.

Conclusion

Our analyses of longitudinal data from the HILDA Survey examine emerging adults—people who are 18–25 years old and who co-reside with parents and receive financial support from them. We find that a majority of young Australians who are 22 years old or younger are dependent in this way and that substantial minorities of 23- to 25-year-olds also meet the definition of being an emerging adult. We also find that the proportion of young people who are emerging adults has grown over time, especially since 2009.

Emerging adulthood is conceptualised to be distinct from both adolescence and from independent adulthood. Consistent with this conceptualisation, we find that young people who are emerging adults have autonomy in some spheres of their lives but not others, while young people who are independent adults have much more autonomy in all the spheres that we can measure. We find that most emerging adults are enrolled in school and therefore investing in better adult opportunities. We also find that most emerging adults work. However, their work often occurs through casual jobs and with low earnings, so they have not completed the adult transition to permanent, economically sustaining work. Similarly, few have made the transition to partnering or to bearing children.

As with many other forms of human development, young people from privileged backgrounds appear to have more opportunities to invest through emerging adulthood. Young people with high-income parents receive co-residential and financial support longer than young people with low-income parents. Similarly, non-Indigenous young people and young people from two-parent families receive support for longer than Indigenous Australians or young people from single-parent backgrounds. However, there are some other patterns, with young people from migrant families and rural areas receiving assistance longer.

References

Angelini, V., Marco, B., & Weber, G. (2020). The long-term consequences of a Golden Nest (Discussion paper no. 13659). Institute of Labor Economics.

Arnett, J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

Arnett, J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73.

Benson, J., & Furstenberg, F. (2006). Entry into adulthood: Are adult role transitions meaningful markers of adult identity? Advances in Life Course Research, 11, 199–224.

Botha, F., Broadway, B., de New, J., & Wong, C. (2020). Financial autonomy among emerging adults in Australia (Working paper No. 30/20). Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research.

Cobb-Clark, D. (2008). Leaving home: What economics has to say about the living arrangements of young Australians. Australian Economic Review, 41(2), 160–176.

Cobb-Clark, D., & Gørgens, T. (2014). Parents’ economic support of young-adult children: Do socioeconomic circumstances matter? Journal of Population Economics, 27(2), 447–471.

Cobb-Clark, D., & Ribar, D. (2012). Financial stress, family relationships, and Australian youths’ transitions from home and school. Review of Economics of the Household, 10(4), 469–490.

Côté, J. (2014). The dangerous myth of emerging adulthood: An evidence-based critique of a flawed developmental theory. Applied Developmental Science, 18(4), 177–188.

Côté, J., & Bynner, J. (2008). Changes in the transition to adulthood in the UK and Canada: The role of structure and Agency in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies, 11(3), 251–268.

Drake, D., Dandy, J., Loh, J., & Preece, D. (2018). Should parents financially support their adult children? Normative views from Australia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39, 348–359.

Elzinga, C., & Liefbroer, A. (2007). De-standardization of family-life trajectories of young adults: A cross-National Comparison Using Sequence Analysis. European Journal of Population, 23(3–4), 225–250.

Fingerman, K., Kim, K., Davis, E., Furstenberg F., Birditt, K., & Zarit, S. (2015). “I’ll give you the world”: Socioeconomic differences in parental support of adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(4), 844–865.

Furstenberg, F. (2010). On a New schedule: Transitions to adulthood and family change. The Future of Children, 20(1), 67–87.

Gillespie, B. (2020). Adolescent intergenerational relationship dynamics and leaving and returning to the parental home. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(3), 997–1014.

Hahn, M., & Haisken-DeNew, J. (2013). PanelWhiz and the Australian longitudinal data infrastructure in economics. Australian Economic Review, 46(3), 379–386.

Hartmann, D., & Swartz, T. (2007). The New adulthood? The transition to adulthood from the perspective of transitioning young adults. Advances in Life Course Research, 11, 253–286.

Hartnett, C., Furstenberg, F., Birditt, K., & Fingerman, K. (2013). Parental support during young adulthood: Why does assistance decline with age? Journal of Family Issues, 34(7), 975–1007.

Johnson, M. (2013). Parental financial assistance and young adults’ relationships with parents and Well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 75(3), 713–733.

Kendig, S., Mattingly, M., & Bianchi, S. (2014). Childhood poverty and the transition to adulthood. Family Relations, 63(2), 271–286.

Mortimer, J., Kim, M., Staff, J., & Vuolo, M. (2016). Unemployment, parental help, and self-efficacy during the transition to adulthood. Work and Occupations, 43(4), 434–465.

Ribar, D. (2015). Is leaving home a hardship? Southern Economic Journal, 81(3), 598–618.

Roisman, G., Masten, A., Coatsworth, J., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development, 75(1), 123–133.

Sandberg-Thoma, S., Snyder, A., & Jang, B. (2015). Exiting and returning to the parental home for boomerang kids. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 806–818.

Schoeni, R. (1997). Private interhousehold transfers of money and time: New empirical evidence. Review of Income and Wealth, 43(4), 423–448.

Settersten, R., & Ray, B. (2010). What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. Future of Children, 20(1), 19–41.

Summerfield, M., Bright, S., Hahn, M., La, N., Macalalad, N., Watson, N., Wilkins, R., & Wooden, M. (2019). HILDA user manual – Release 18. Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research.

Swartz, T., McLaughlin, H., & Mortimer, J. (2017). Parental assistance, negative life events, and attainment during the transition to adulthood. Sociological Quarterly, 58(1), 91–110.

Wong, C. (2018). Challenges in early adulthood and the timing of Nest-leaving. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Melbourne.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Janeen Baxter and Deborah Cobb-Clark for many helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ribar, D.C., Wong, C. (2022). Emerging Adulthood in Australia: How is this Stage Lived?. In: Baxter, J., Lam, J., Povey, J., Lee, R., Zubrick, S.R. (eds) Family Dynamics over the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-12223-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-12224-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)