Abstract

This chapter analyzes the configuration of global value chains in the digital entrepreneurship age by clarifying past contributions, examining work resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, and outlining suggestions for future research. First, we provide a conceptual framework to understand how digitalization has driven its transformation. Specifically, we discuss the main changes in the slicing of value chain activities, the control and location decisions of these activities, and the paradoxical role played by digital technologies in shaping the way entrepreneurs organize them. In doing this, we highlight the location paradox, which rests on the idea that digital technologies help firms expand their geographical scope and reduce co-ordination costs in large and dispersed networks (which favors offshoring), while reducing the importance of the location of activities and shortening supply chains (which favors reshoring). Second, we critically review the research on value chain configurations that has appeared because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Lastly, we discuss some promising areas of research that could yield insights that will advance our understanding of value chain configurations in the digital entrepreneurship age.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Digitalization is a key driver of the transformation of global value chains (GVCs) (Cennamo et al., 2020; McKinsey Global Institute, 2019; Zhan, 2021), one that affects the slicing of value chain activities as well as location and governance decisions (Brun et al., 2019). A transformation of this kind presents opportunities for entrepreneurs to discover previously unknown business opportunities and for established firms to exploit the restructuring of the value chain to launch entrepreneurial ventures.

The debate over the re-shaping of GVCs has gained even greater importance because of the disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. In particular, numerous studies argue in favor of bringing offshored activities closer to home and relying—among other measures—on digital technologies (DTs) to reduce the risks of supply shortages (Ivanov & Dolgui, 2020). DTs can, in this way, help firms that have offshored some of their activities to re-focus on neighboring countries or regions or even re-shore them to the home country.

The profound and varied changes that DTs bring to GVCs make it advisable to adopt a comprehensive approach. This is the purpose of this chapter. To do this, we provide a conceptual framework to understand the changes in the configuration of value chains in the digital entrepreneurship age. This analysis leads us to a discussion of the paradoxical consequences that digitalization appears to be bringing to the design of GVCs, especially in regard to the location of activities. The International Business literature views DTs as tools that help firms expand their geographical scope and reduce co-ordination costs in large, dispersed networks of subsidiaries, suppliers, and customers (Alcácer et al., 2016; Chen & Kamal, 2016). Paradoxically, however, the growth of these technologies is an enabler of reshoring (Dachs et al., 2019a), which leads to shorter, less-fragmented value chains and greater geographical concentration of value-added activities (Zhan, 2021).

In addition, we are particularly interested in clarifying the changes Covid-19 has brought to GVCs and how they differ from previous restructurings. The pandemic has presented opportunities to launch new businesses that rely on DTs and take advantage of the restructuring of GVCs (Davidsson et al., 2021).

The remainder of the chapter is organized as follows. First, we define what we understand by digital entrepreneurship and outline the main characteristics of DTs and how these may influence the configuration of value chains. Second, we provide an overview of the configuration of GVCs in the digital entrepreneurship age, with special attention paid to location decisions and the paradoxical role played by DTs. Third, we critically review recent studies on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on value chain configurations. We close the chapter by discussing several avenues for further research at the intersection of the digital entrepreneurship and GVC literatures. We hope the discussion of these promising streams will yield insights that will advance our understanding of the value chain configuration in the digital entrepreneurship age.

2 Digital Entrepreneurship and the Value Chain Configuration

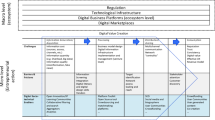

We open this chapter by introducing a framework for understanding the value chain configuration in the digital entrepreneurship age (see Fig. 1); this framework will be explained and referred to throughout the chapter. On the one hand, the proposed framework presents the key elements that define digital entrepreneurship (see Sect. 2.1), together with the characteristics of DTs that facilitate the re-shaping of GVCs (see Sect. 2.2). And on the other, it identifies the key decisions necessary to reconfigure the value chain, with particular reference to location decisions (see Sect. 2.3). The framework also considers the impact of Covid-19. The pandemic is a new re-shaper of GVCs, one that also influences the impact of digitalization on them (see Sect. 3).

2.1 Digital Entrepreneurship and Global Value Chains

Digital entrepreneurship has received considerable attention from scholars from different disciplines over recent years, a state of affairs reflected by the numerous special issues and reviews dedicated to it (e.g., Kraus et al., 2019; Lanzolla et al., 2020; Sahut et al., 2021; Steininger, 2019). A multitude of definitions of digital entrepreneurship has been put forward in the last decade (e.g., see Sahut et al., 2021). On the left-hand side of Fig. 1, we summarize the concept of digital entrepreneurship used in this chapter. Specifically, we define digital entrepreneurship as new economic ventures or transformations of current businesses based on the application of DTsFootnote 1 in at least three primary ways (von Briel et al., 2021), namely by: (a) creating a value proposition or business model; (b) producing, commercializing, or delivering the value proposition; and (c) operating in the digital context.

The creation of a digital outcome is not the only manifestation of digital entrepreneurship. In our framework, new and preexisting firms that use DTs to modify their processes (e.g., via the application of Industry 4.0 or additive manufacturing) or that offer physical products accompanied by digital services form part of the digital universe.Footnote 2 In fact, some firms—and new ventures—are more digitalized than others (Monaghan et al., 2020). For example, a “dark kitchen” that exclusively offers food for home delivery and that uses the internet to manage orders and staff, as well as administer review sites, social media promotions, etcetera is more digitalized than a larger restaurant that uses social networks simply to promote the business.

Digital business activity, then, is supported by highly distinct forms of DTs, such as digital artifacts (e.g., digital components, applications, or media content), digital platforms, and digital infrastructures (e.g., cloud computing, big data analytics, online communities, social media, additive manufacturing, digital makerspaces, etcetera) (Nambisan, 2017).

Digitalization opens opportunities for both new players and preexisting firms. DTs positively affect all stages of entrepreneurship, making it possible to identify or create new opportunities; facilitate viability studies; and in many cases get new businesses started. They are especially useful to firms in search of opportunities and eager to operate in an international context. DTs allow new ventures to create value for final markets and more easily insert themselves into GVCs and new types of ecosystems. In the case of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), both the International Business and GVC literatures view these firms as dependent suppliers operating in value chains led by multinational companies (Oliveira et al., 2021). Inserting themselves into GVCs has been the most common way of internationalizing for SMEs, a strategy which places them in a position of total dependency. DTs, though, have increased the autonomy of SMEs when working with leading multinational companies (Sturgeon, 2021; Oliveira et al., 2021). For example, DTs now permit SMEs to gain access to digital platforms and ecosystems as well as establish links with other types of partners (Pananond et al., 2020) and subsequently obtain the resources needed to innovate. In general, DTs give SMEs the opportunity to upgrade what they offer and deliver it to a much wider market.

2.2 Characteristics of Digital Technologies and Their Implications for the Configuration of Global Value Chains

DTs offer affordances that can be useful to identify, analyze, and exploit business opportunities. The most prominent of these are reprogrammability, generativity, disintermediation, and scalability (see Fig. 1) (Autio et al., 2018; Monaghan et al., 2020; Nambisan, 2017; Yoo et al., 2010; Zaheer et al., 2019).

Reprogrammability simply means that an asset can be reprogrammed to perform different functions, thereby reducing its specificity and lowering the transaction costs. In fact, digital assets can be used for multiple applications with no loss of value. Digitalization increases the flexibility of the organization while reducing levels of dependency and opportunistic behavior of suppliers or clients.

Generativity relates to the capacity to recombine elements creatively and use them for previously unimagined purposes. The open and flexible affordances of pervasive DTs enable them to develop unforeseen innovations on a constant basis, in many cases involving new actors in an uncoordinated mode (Yoo et al., 2012). In combinatorial innovations, the boundaries of the product are not fixed, but are fluid. Thus, the designers of a component cannot fully know how the component will be used with their product or all the possible ways that the product could be used as a component. In sum, products can be used in multiple ways or in combination with others (Yoo et al., 2010), as occurs, for example, with the smartphone.

Disintermediation refers to the possibility of establishing direct relationships between providers and users, thus eliminating intermediaries and the power they may exert. Marketplaces, for example, present all types and sizes of firms with opportunities for direct access to final customers.

Lastly, scalability is linked to the capacity to grow rapidly and span extremely large markets, without the need to worry about temporal diseconomies or requirements for the same level of resources as traditional brick-and-mortar businesses, thanks to the greater use of lighter assets (Banalieva & Dhanaraj, 2019). A good example of global scaling is provided by Wattpad, a social storytelling platform with a small employee base in Canada that serves more than 70 million users worldwide (for more details see Monaghan et al., 2020).

DTs, then, are versatile tools that boost flexibility and promote innovation, ones that reduce the importance of the location of activities (Autio et al., 2018), grant more autonomy to firms, and allow them to attend to new demand requirements. For this reason, they are particularly useful for insertion into GVCs (Monaghan et al., 2020).

Many DTs are applicable to the design and management of value chains. Additive manufacturing (3D printing), big data analytics, advanced tracking and tracing technologies, cloud computing and artificial intelligence (AI)—along with the internet of things, and mobile telephone-based and social media-based systems (Ivanov et al., 2019; Winkelhaus & Grosse, 2020; Koh et al., 2019)—are all relevant. And yet, not all these technologies are equally advanced or equally applicable to the internationalization of firms and their value chains (Strange & Zucchella, 2017). Many of them, though, are not only being used to improve the management of value chains, but also to shorten and completely re-design them.

2.3 An Overview of the Value Chain Configuration in Digital Entrepreneurship: The Paradoxical Role of Digital Technologies

The digital transformation is driving changes in firms’ boundaries, processes, structures, roles, and interactions (Cennamo et al., 2020). And these changes equally affect new ventures and preexisting firms that seek to transform their business models. In both cases, the incorporation of DTs brings a reconfiguration of value chains (Strange & Zucchella, 2017) and affects decisions on what activities to disaggregate, how to manage them, and where to locate them (see the right-hand side of our framework in Fig. 1). We shall now proceed to discuss some of the main changes that DTs have brought to the value chain configuration, many of which are paradoxical (see Table 1 for an overview).

2.3.1 DTs and Value Chain Activities: The Slicing of Activities

DTs exert an impact on the activities of the whole value chain, ranging from product design and manufacturing to distribution (Koh et al., 2019). They improve the planning and coordination of activities and thus facilitate the disintegration of the value chain, permitting activities to be performed in the most advantageous and efficient locations. This suggests that DTs are crucial tools to manage a more finely sliced and internationally dispersed value chain. Both manufacturing and service activities—especially those based on knowledge—have been offshored across borders in recent decades (Contractor et al., 2010; Pisani & Ricart, 2016).

Service activities are especially benefited by DTs that improve communication, technologies such as teleconferencing, cloud storage, 5G, virtual reality, and augmented reality. These technologies all improve efficiency and interaction among dispersed locations, particularly higher value-added knowledge-based activities, even in sectors such as health care (Buckley, 2021). In addition, DTs make it possible to unbundle manufacturing activities into services that can be supplied independently, thereby enabling greater servitization, which facilitates further fragmentation of the value chain into increasingly finely sliced pieces (Brun et al., 2019).

At the same time, DTs paradoxically allow digital entrepreneurs to shorten the length of these value chains and reduce the fragmentation of the activities included in them (Zhan, 2021). An example of this is additive manufacturing, which has the potential to modify the density of GVCs (as well as geographic span) (Laplume et al., 2016). This re-shaping of the value chain can result in more concentrated value-added in the countries in which the digital coordination of the value chain is performed (Buckley et al., 2020). Moreover, DTs make it possible to minimize waste in manufacturing activities and thereby achieve higher efficiency-sustainability levels.

2.3.2 DTs and Control of Value Chain Activities: Make, Buy or Ally?

Together with the slicing of activities, another important aspect is determining how to organize them. It is important to decide, therefore, whether each activity to be disaggregated will be performed internally (via subsidiaries or affiliates) or externally (via outsourcing contracts or collaboration agreements).

Digitalization reduces transaction costs for both internal and external operations (Banalieva & Dhanaraj, 2019) thanks, among other things, to the fact that DTs help to manage information better (such as those related to big data analytics) and to make transactions more secure (such as those related to blockchain). DTs clearly exert effects—in ways that in many cases are once again paradoxical—on the governance modes.

First, reduced transaction costs for internal operations may persuade firms to perform activities in-house. As explained, DTs contribute to disintermediation, which favors the adoption of internal governance modes and the shortening of the value chain. DTs, then, enable firms to dispense with third parties (suppliers or collaborators) and open the door for them to take on the different functions themselves, both direct provision (thanks to supply chain digitalization) and/or direct distribution to the customer. Instances of this can be seen in digital media businesses with data streaming services that offer digital content directly to customers (e.g., Twitch, a live streaming platform (https://www.twitch.tv/). Similarly, the ease with which large quantities of data can be acquired and managed, along with the capacity to verify the security of transactions, is making it possible to take on supporting activities such as financial services (Brun et al., 2019). Moreover, we must not forget the importance of data for digital businesses—they are often the core elements of the business. Properly controlling and using this information, then, is crucial for the competitiveness of firms and is another factor that motivates them to manage the acquisition, handling, and storage of data internally.

Second, the reduction of external transaction costs facilitates external governance modes. Possessing and analyzing large quantities of data, together with the security delivered by blockchain technology, encourages the use of markets (e.g., via smart contracts). And yet these same technologies are also fundamental for the establishment of cooperative relationships between partners. Digitalization enables the control of assets without ownership and the access to/control of workers without an employment relationship (Gawer, 2020). Cooperative relationships, then, take precedence and favor the creation of ecosystems made up of complementary firms. Likewise, DTs are responsible for the extraordinary proliferation of digital platforms (Cusumano et al., 2019), both transaction platforms that enable exchanges between different sides (such as Shopify, Magento or OpenCart) and innovation platforms (such as Wazocu, Herox or OPEN Ideo).Footnote 3

Lastly, it is important to note that in digital business relationships the distribution and transfer of large quantities of information between different actors increases the need for improved cybersecurity. This need not only influences the choice of partners but is also likely to persuade firms to internalize sensitive activities.

In sum, DTs simultaneously favor the adoption of conflicting governance modes in the configuration of GVCs. On the one hand, they promote vertical integration. And on the other, the same technologies favor and support external modes such as cooperation with customers and suppliers, as well as agreements with independent third parties.

2.3.3 DTs and Location of Value Chain Activities: Offshoring and Reshoring Dynamics

Another key decision linked to the configuration of the value chain is where to locate activities—in the home country or some other country or region. To make the best decision, entrepreneurs should analyze the interaction between the comparative advantages of the country and the firm (Kogut, 1985). In recent decades this analysis has led firms to disperse their value chains internationally, in search of—among other things—more competitive costs and/or higher quality resources. The characteristics of DTs, however, can modify this interaction, favoring both the dynamics of offshoring and reshoring (or backshoring).

The changes brought by digital entrepreneurship have reduced the importance of labor arbitrage in deciding where best to locate value activities and put the spotlight on other elements. Factors like regulatory quality (e.g., the ability of institutions to protect data), the availability of a digitally skilled workforce, and the existence of a digital technological infrastructure are prime concerns. Given the importance of the information and data that are collected in digital entrepreneurship, it is also vital to uphold standards and enforce regulations. For this reason, digital security and cybersecurity have become determining factors in location strategies (Buckley, 2021). The location-specific technological context assumes, then, greater importance, in particular the quality of the digital-industrial ecosystem in a firm’s home country versus that offered by the overseas location (Kamp & Wilson, 2021). Accordingly, in recent years digital resonanceFootnote 4 has emerged as a decisive factor in location decisions (see AT Kearney, 2021). Lastly, we must not forget to mention other factors such as the strategy of the firm, the need to configure resilience-oriented value chains, institutional pressures, and the requirements of sustainability, all of which play roles in the location decision.

The application of DTs to the design of GVCs appears to be producing a paradoxical effect in the location of value chain activities (i.e., offshoring/reshoring). This location paradox rests on the idea that DTs help firms expand their geographical scope and reduce co-ordination costs in large and dispersed networks (which favors offshoring), while reducing the importance of the location of activities and shortening supply chains (which favors reshoring). Both options offer a multitude of opportunities for digital entrepreneurs.

DTs favor offshoring strategies because they make it possible to manage finely sliced value chains spread all over the world, one of whose consequences has been the appearance of global factories (Buckley, 2009). The layered and modular character of many DTs (Sturgeon, 2021), the use of big data to program production, and improved capacities to coordinate dispersed activities, for example, facilitate offshoring. In addition, technologies that support remote interaction promote the offshoring of high- and medium-level value-added services. Given the increased need for digital capacity among businesses that rely on DTs for their cross-border activities, digital resonance remains crucial to take advantage of offshoring strategies.

Conversely, the advanced features of many DTs mean that firms can re-locate activities at home or in neighboring countries with no increase in production costs (and lower transport costs). In addition, firms obtain other benefits that are indispensable to compete in many markets, advantages such as the ability to respond in a timely and efficient manner to individual consumer demands. Digital technologies such as additive manufacturing or automation promote reshoring. Indeed, these technologies and others like them not only bring supply chains closer to destination markets, but also oblige an overhaul and reduction of the activities included in them. Thus, DTs enable more efficient and sustainable production and processes, as shortened value chain configurations reduce trade and transport flows and their negative effects.

DTs, then, seem to make the offshoring of manufacturing less attractive by providing alternatives to the international dispersion of production (De Backer & Flaig, 2017). The link between DTs and backshoring strategies is not clear, however (Kamp & Gibaja, 2021). The few studies that have examined this relation to date find contradictory—and therefore inconclusive— results (see Ancarani et al., 2019; Ancarani & Di Mauro, 2018; Dachs et al., 2019a; Fratocchi & Di Stefano, 2019; Müller et al., 2017). It is certainly possible, of course, that the paradoxical role of DTs may have something to do with these inconclusive results.

3 The Current Context: An Overview of Research on the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The current state of GVCs and digital entrepreneurship is marked by the Covid-19 pandemic. Since international supply chains have been particularly affected, discussion has centered on the international distribution of value chain activities. Supply problems have resulted in shortages of essential products. The lack of components in many industrial sectors, a consequence of cascading “ripple effects” (Ivanov et al., 2014), has paralyzed production in numerous sectors. At the same time, the demand for many products has plummeted, causing stocks of unsold products to rise in some sectors (e.g., textiles). The combination of a risk demand with a supply risk (van Hoeck, 2020a) has stressed supply chains to an extraordinary degree.

This situation has led academics (Miroudot, 2020; Strange, 2020; Verbeke, 2020) and consultants (Accenture, 2021; McKinsey, 2021) to question and seek improvements to the design and management of value chains. Interest has focused on the risks posed by highly infrequent events with extreme consequences such as pandemics or natural disasters. What has become clear is that in addition to preparing better for tragedies of this kind, a revamp of the design of value chains is called for, particularly in regard to the international distribution of activities.

Supply chain resilience has become a requirement (Strange, 2020), one that may turn into an important strategic weapon (Scholten et al., 2020), not only as a recovery mechanism to unexpected events but. in a more ambitious sense, also as a means of adapting to and improving after changes, and thus reinforcing the viability of firms (Ivanov & Dolgui, 2020; Wieland & Durach, 2021). The question to be answered is how to build this resilience. In the short time that has passed since the beginning of the pandemic, numerous studies have appeared that look for answers (see Chowdhury et al., 2021 for a survey). Many of these studies stress the need to develop optimization and simulation methodologies (Golan et al., 2020; Queiroz et al., 2020). Beyond this, however, a series of responses more related to strategy and management are frequently mentioned, among which the following stand out:

-

Considering total costs including sourcing, supply and servicing, and designing new ways of working (McKinsey, 2021; van Hoeck, 2020b)

-

Improving relationships with suppliers and customers (McKinsey, 2021; van Hoeck, 2020a)

-

Re-locating value chain activities closer to home (Accenture, 2021; Barbieri et al., 2020; McKinsey, 2021; Fratocchi & Di Stefano, 2020; Queiroz et al., 2020; van Hoeck, 2020a; Wieland & Durach, 2021)

-

Adopting digital technologies (DTs) such as blockchain, artificial intelligence, Industry 4.0, and additive manufacturing (Chowdhury et al., 2021; El Baz & Ruel, 2021; Queiroz et al., 2020)

3.1 Covid-19 and the Design of GVC Activities. Has Anything Changed in Today’s ‘New Normal’?

The question to be asked is whether the proposals put forward in recent studies of the value chain configuration in the Covid-19 pandemic are new. To answer this question, we should bear in mind that the fragmentation and spatial distribution of value chain activities caused by offshoring seems to have peaked in 2010, at least in manufacturing activities. In line with this, macroeconomic data confirm that the offshoring of manufacturing has become less common since then (UNCTAD, 2020; World Trade Organization, 2021). At the same time, the reshoring of value chain activities was already a growing phenomenon (The Economist, 2013). Poor quality, lack of flexibility, unemployed capacity at home, and overly high sourcing costs, including coordination and logistics costs, have become the primary causes of the reshoring of manufacturing activities. Innovation issues such as the proximity of production to R&D seem to be secondary drivers (Dachs et al., 2019b). Some of these reshorings were caused by dissatisfaction with offshoring, while others were the result of a change in strategy (McIvor & Bals, 2021).Footnote 5 Overall, DTs have given a huge boost to the dynamic of re-locating value chain activities (Ancarani et al., 2019; Dachs et al., 2019a; Stentoft & Rajkumar, 2020).

Reshoring, then, was a strategy that numerous firms were implementing before Covid-19Footnote 6 because competitive demands made it a necessity and technology was available that made it feasible. Other contextual changes such as growing protectionism and particularly the non-negotiable need for sustainability are also promoting the decision to opt for reshoring.

Although there has been much talk of the post-Covid era and the “new normal,” how GVCs have changed and will continue to change was already being discussed before the arrival of the pandemic. Indeed, “a new normal” in the configuration of GVCs had already been mentioned in pre-Covid-19 times (De Backer & Flaig, 2017), and Brun et al. (2019) argue that the consequences of the 2008 financial crisis for GVCs were resiliency, regionalization, rationalization, and digitalization.

Covid-19 has speeded up a process that had already been initiated. Firms have accelerated their digitalization processes; their employees are working from home; and their customers have become used to buying online. In parallel, research into DTs continues to grow, along with investment in infrastructure designed to boost global connectivity. Without doubt, the Covid-19 pandemic has hastened the massive use of DTs in society as a whole and in the business world. Firms that take advantage of the spur to digitalize provided by Covid-19 will boost their competitiveness. Likewise, this digitalization process will present numerous opportunities for new digital entrepreneurs.

4 Avenues for Future Research: Insights for GVC ‘Location Decisions’ in the Digital Entrepreneurship Age

The study of the value chain configuration in the digital entrepreneurship age offers many unexplored lines of research. Our objective in this chapter was to present a general framework for the study of the relation between digitalization and the reconfiguration of GVCs, along with the opportunities offered for digital entrepreneurship; this framework can be used as a starting point for future analyses. Specifically, we were particularly interested in the dimension of location, as the notion that “‘digital affordances are not location specific” (Autio et al., 2018, p. 16) seems to make it likely that DTs will challenge or even alter our beliefs about the location of activities in the value chain. Indeed, the impact of DTs is one of the least investigated yet most promising areas in the study of GVCs and International Business (Kano et al., 2020).

In accordance with the framework discussed, we outline three opportunities for further research: (1) the specificities of different DTs and locations; (2) new digital business models; and (3) digital sustainability.

4.1 The Specificities of Different DTs and Locations: Clarifying the Paradoxical Role of DTs?

To this point, we have referred to DTs in general, but many types of DTs exist, with distinct characteristics and levels of maturity. We need, then, to disentangle the different digital technologies and their implications for the location of activities in the value chain.

An in-depth analysis of each DT may help to clarify their paradoxical roles. In principle, some of these technologies are likely to be particularly useful for coordinating dispersed activities across borders, whereas others will sustain re-shored activities. De Backer and Flaig (2017), for example, suggest that communication technologies will continue to support offshoring, while information technologies will promote reshoring. Each DT, then, requires study to determine how it may contribute to firm competitiveness. Such an examination will also help explain the conflicting results obtained by current empirical research. Although most studies confirm the relation between DTs and reshoring (Ancarani et al., 2019; Dachs et al., 2019a; Stentoft & Rajkumar, 2020), some papers suggest that the importance of DTs for reshoring is questionable (Ancarani & Di Mauro, 2018, Müller et al., 2017).

The business model of the firm along with the value levers that underpin it are key elements that should guide the application of DTs to the design of GVCs. Flexibility, time to market, and superior quality or efficiency are some of the main value levers whose relations with different DTs and GVC designs should be studied in detail. Advancing our knowledge of which lever or levers each DT favors and how they can be used represents a clear source of opportunities for new entrepreneurs seeking to insert themselves into GVCs or construct their own supply chains. Lastly, research is needed into the impact of a series of contextual elements. Chief among these are the existence of qualified personnel, adequate infrastructure, and a developed legal and regulatory framework.

4.2 New Digital Business Models: Value Chain Upgrading and Entrepreneurial Opportunities

DTs open numerous opportunities for innovation and the development of new digital business models, especially ones with implications for GVCs (Brun et al., 2019; Strange & Zucchella, 2017). They have given rise to less bounded entrepreneurial outcomes and processes that have opened the locus of entrepreneurial agency to a varied and changing group of actors (Nambisan, 2017). DTs produce a distributed entrepreneurial agency, with multiple parties involved in the development of the idea and the supply of the resources necessary for the project via instruments such as crowdfunding, social media platforms, and digital marketplaces, among others—an approach that favors disintermediation and the birth of ecosystems (Zaheer et al., 2019). In short, digital entrepreneurship offers a multitude of opportunities for entrepreneurs (Nambisan & Baron, 2021) via such ecosystems and platforms (Gawer, 2020).

Digital platforms make it easier to set up businesses and quickly break into international markets. The phenomenon of platformization offers many novel research opportunities (Kano et al., 2020). Industrial digital platforms that focus on B2B relationships merit particular attention as this is an area that has not received sufficient study in the literature on platforms (Jovanovic et al., 2021).

Platforms and digital tools in general are making it possible for SMEs to gain more autonomy from multinational enterprises. These tools allow SMEs to create more value, while also giving them increased power to obtain a substantial part of this value. How value is created within GVCs and how it is distributed among partners in the value chain is a crucial question to analyze (Ghauri et al., 2021). Since the distribution of value depends on the relative power of each partner, power relationships in GVCs need to be investigated, along with how the re-design of GVCs has affected these relationships. The literature on the governance of GVCs is particularly interested in how power asymmetries may inhibit or facilitate supplier upgrading (McWilliam et al., 2020). The model developed by Oliveira et al. (2021) throws light on the unaddressed effects of digital technologies on power relationships in value chains, relationships that constrain the ability of SMEs to upgrade. In sum, many questions remain unanswered, and more research is needed to deepen our current understanding of value chain upgrading and digital entrepreneurship.

It should not be forgotten that entrepreneurship comes with a price tag, and that digital entrepreneurship has specific costs that arise from the characteristics of DTs. Many platforms and ecosystems, for example, require input standardization, which makes suppliers, especially SMEs, more interchangeable and consequently vulnerable (Nambisan et al., 2019). Platforms bring other limitations that are the result of lock-in effects (Cutolo & Kenney, 2020). The initial advantages that they deliver for gaining access to international markets (e.g., lower entry costs and reduced risk) can turn into a dependency on the platform owner, another danger to add to the specific risks that new ventures face when internationalizing (Jean et al., 2020). This situation opens several important avenues for future research to concentrate on understanding and calculating the costs of digital entrepreneurship (Nambisan & Baron, 2021).

Lastly, we must mention the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the entrepreneurial opportunities that this has presented (Davidsson et al., 2021). The digitalization of the economy and the re-design of GVCs were already research topics before the arrival of Covid-19. And yet, the pandemic has sharpened the focus on digital business models and the changes they have brought to GVCs. Resilience and viability have become key issues in the design and management of the new value chain (Ivanov, 2020), and as such these areas should receive attention from future work. In the end, the most important impact of the pandemic may well be the boost it has given to digitalization in all contexts, to businesses and to other aspects of our daily lives. Digital operating models with exponential growth trajectories have been shown to be highly useful to compete against and outperform incumbents with fixed capabilities (George et al., 2020). Thus, the potential of digital businesses and the entrepreneurial opportunities they create are clear and merit further research.

4.3 Digital Sustainability and Location in Digital Entrepreneurship

The sustainability of supply chains has received extensive attention from researchers over the last 20 years, but almost always focused on the context of large firms. Even though SMEs make up the majority of businesses in all countries and possess huge potential to reach sustainable development goals (Sinkovics et al., 2021), few studies of the sustainability of supply chains in these firms exist. This is a research gap that should be filled.

Since their appearance in the 1980s, GVCs have grown ever more complex and long, resulting in an increase in international—particularly maritime—transport (De Backer & Flaig, 2017), which has in turn had detrimental effects for the environment. And this, of course, is not the only negative consequence caused by the proliferation of GVCs. Pollution and the squandering of natural resources in countries where activities are located are just two more—among many other—of their negative impacts. On the positive front, GVCs have generated employment, upped the standard of living, and even improved the technological endowment of host countries.

The logistical pressure is also ratcheted up by consumers who nowadays expect to receive their orders almost immediately, with the concomitant effects of last mile delivery. Time-to-market has become a key value lever, with all the negative consequences this brings for the environment.

Although reshoring and sustainability are clearly related, up to now this relation has been largely neglected by scholars (Fratocchi & Di Stefano, 2019; Orzes and Sarkis, 2019). Locating activities closer to target markets reduces the need for—and negative effects—of transport. Moreover, production is transferred to countries with tougher environmental standards and laws. Lastly, automation and agile manufacturing, both so important for the efficiency of reshoring, contribute to waste reduction (The Reshoring Institute, 2020).

DTs play a fundamental role in the sustainability of GVCs (Roozbeh Nia et al., 2020). The use of 3D printing, which constructs without generating waste, is a good example. Big data analytics and cloud computing help to identify precisely what each consumer wants, thereby minimizing unsold products and unproductive stock. Indeed, some of the firms that weathered the hardships of the pandemic best were those that produced small batches in response to demand.

Digital sustainability, then, merits attention from future studies. A key issue to examine is how the characteristics of DTs can be used to reach sustainable development goals (George et al., 2021). An examination of the intersection between the literatures of digital entrepreneurship, GVCs, and sustainability could be hugely important for the configuration of more sustainable value chains.

5 Concluding Remarks

In this chapter, we have examined the relation between digital entrepreneurship and GVCs. In doing this, we have highlighted the way DTs have transformed value chains and provided opportunities for new ventures to integrate themselves into them, as well as upgrading the value propositions of the SMEs that are already a part of them.

The characteristics of DTs modify traditional GVC configurations in terms of slice, governance mode, and location of activities, promoting in many cases contradictory—apparently paradoxical—decisions. The dynamic of location is particularly interesting because DTs simultaneously favor offshoring and reshoring strategies.

Moreover, digitalization and reshoring are two of the most commonly mentioned strategies to deal with future supply problems caused by Covid-19 type disruptions. Both strategies were analyzed by scholars and consultants before the pandemic demonstrated their worth. In particular, the incorporation of DTs into business models was on the agenda of many companies long before the pandemic broke out. Covid-19 has accelerated this digital transformation, a transformation upon which many sustainable competitive advantages for firms will depend in the future.

Lastly, we present three areas of opportunity for further research linked to: the specificities of different DTs and locations; new digital business models; and digital sustainability.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

Digital resonance is informed by metrics like the digital skills of a country’s workforce, legal and cybersecurity, corporate investment in startups, and digital innovation outputs.

- 5.

In essence, the two types of causes of re-shoring can be identified, in both manufacturing and service sectors (Albertoni et al., 2017).

- 6.

In fact, universal agreement does not exist on whether the present situation requires GVC activities to be re-shored; Miroudot (2020) argues that the literature on risk supply management has not demonstrated that domestic production generates more resilience.

References

Accenture. (2021). Make the leap, take the lead.Tech strategies for innovation and growth. Retrieved from https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-153/Accenture-Make-The-Leap-Take-The-Lead-Report.pdf

Albertoni, F., Elia, S., Massini, S., & Piscitello, L. (2017). The reshoring of business services: Reaction to failure or persistent strategy? Journal of World Business, 52(3), 417–430.

Alcácer, J., Cantwell, J., & Piscitello, L. (2016). Internationalization in the information age: A new era for places, firms, and international business networks? Journal of International Business Studies, 47, 499–512.

Ancarani, A., & Di Mauro, C. (2018). Reshoring and Industry 4.0: How Often Do They Go Together. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 46(2)., June 2018. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2018.2833475

Ancarani, A., Di Mauro, C., & Mascali, F. (2019). Backshoring strategy and the adoption of industry 4.0: Evidence from Europe. Journal of World Business, 54(4), 360–371.

Autio, E., Nambisan, S., Thomas, L. D., & Wright, M. (2018). Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 72–95.

Banalieva, E. R., & Dhanaraj, C. (2019). Internalization theory for the digital economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 50, 1372–1387.

Barbieri, P., Boffelli, A., Elia, S., Fratocchi, L., Kalchschmidt, M., & Samson, D. (2020). What can we learn about reshoring after Covid-19? Operations Management Research, 13(3), 131–136.

Brun, L., Gereffi, G., & Zhan, J. (2019). The “lightness” of industry 4.0 lead firms: Implications for global value chains. In P. Bianchi, C. R. Durán, & S. Labory (Eds.), Transforming industrial policy for the digital age. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Buckley, P. J. (2009). Internalisation thinking: From the multinational enterprise to the global factory. International Business Review, 18, 224–235.

Buckley, P. J. (2021). Exogenous and endogenous change in global value chains. Journal of International Business Policy, 1–7.

Buckley, P. J., Strange, R., Timmer, M. P., & de Vries, G. J. (2020). Catching-up in the global factory: Analysis and policy implications. Journal of International Business Policy, 3, 79–106.

Cennamo, C., Dagnino, G. B., Di Minin, A., & Lanzolla, G. (2020). Managing digital transformation: Scope of transformation and modalities of value co-generation and delivery. California Management Review, 62(4), 5–16.

Chen, W., & Kamal, F. (2016). The impact of information and communication technology adoption on multinational firm boundary decisions. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(5), 563–576.

Chowdhury, P., Paul, S. K., Kaisar, S., & Moktadir, M. A. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic related supply chain studies: A systematic review. Transportation Research Part E, 148, 102271.

Contractor, F. J., Kumar, V., Kundu, S. K., & Pedersen, T. (2010). Reconceptualizing the firm in a world of outsourcing and offshoring: The organizational and geographical relocation of high-value company functions. Journal of Management Studies, 47(8), 1417–1433.

Cusumano, M. A., Gawer, A., & Yoffie, D. B. (2019). The business of platforms: Strategy in the age of digital competition, innovation, and power. Harper Business.

Cutolo, D., & Kenney, M. (2020). Platform-dependent entrepreneurs: Power asymmetries, risks, and strategies in the platform economy. Academy of Management Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2019.0103

Dachs, B., Kinkel, S., & Jäger, A. (2019a). Bringing it all back home? Backshoring of manufacturing activities and the adoption of industry 4.0 technologies. Journal of World Business, 54(6), 101017.

Dachs, B., Kinkel, S., Jäger, A., & Palčič, I. (2019b). Backshoring of production activities in European manufacturing. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 25(3), 100531.

Davidsson, P., Recker, J., & von Briel, F. (2021). COVID-19 as external enabler of entrepreneurship practice and research. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 24(3), 214–223.

De Backer, K., & Flaig, D. (2017). The future of global value chains: Business as usual or “a new normal”? In OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 41. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/d8da8760-en

El Baz, J., & Ruel, S. (2021). Can supply chain risk management practices mitigate the disruption impacts on supply chains’ resilience and robustness? Evidence from an empirical survey in a COVID-19 outbreak era. International Journal of Production Economics, 233, 107972.

European Commission (2015). Digital transformation of European industry and enterprises: a report of the strategic policy forum on digital entrepreneurship. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/report-digital-transformation-european-industry-and-enterprises_en

Fratocchi, L., & Di Stefano, C. (2019). Does sustainability matter for reshoring strategies? A literature review. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 12(3), 449–476.

Fratocchi, L., & Di Stefano, C. (2020). Do industry 4.0 technologies matter when companies backshore manufacturing activities? An explorative study comparing Europe and the US. In M. Bettiol, E. Di Maria, & S. Micelli (Eds.), Knowledge management and industry 4.0 (pp. 53–83). Springer.

Gawer, A. (2020). Digital platforms’ boundaries: The interplay of firm scope, platform sides, and digital interfaces. Long Range Planning, 54, 102045.

George, G., Lakhani, K. R., & Puranam, P. (2020). What has changed? The impact of Covid pandemic on the technology and innovation management research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 57(8), 1754–1758.

George, G., Merrill, R. K., & Schillebeeckx, S. J. (2021). Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 999–1027.

Ghauri, P., Strange, R., & Cooke, F. L. (2021). Research on international business: The new realities. International Business Review, 30(2), 101794.

Giones, F., & Brem, A. (2017). Digital technology entrepreneurship: A definition and research agenda. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(5), 44–51.

Golan, M. S., Jernegan, L. H., & Linkov, I. (2020). Trends and applications of resilience analytics in supply chain modeling: Systematic literature review in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Environment Systems and Decisions, 40, 222–243.

Ivanov, D. (2020). Viable supply chain model: Integrating agility, resilience and sustainability perspectives—Lessons from and thinking beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Operations Research, 1–21.

Ivanov, D., & Dolgui, A. (2020). Viability of intertwined supply networks: Extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Production Research, 58(10), 2904–2915.

Ivanov, D., Dolgui, A., & Sokolov, B. (2019). The impact of digital technology and industry 4.0 on the ripple effect and supply chain risk analytics. International Journal of Production Research, 57(3), 829–846.

Ivanov, D., Sokolov, B., & Dolgui, A. (2014). The ripple effect in supply chains: Trade-off ‘efficiency-flexibility-resilience’in disruption management. International Journal of Production Research, 52(7), 2154–2172.

Jean, R.-J., Kim, D., & Cavusgil, E. (2020). Antecedents and outcomes of digital platform risk for international new ventures’ internationalization. Journal of World Business, 55(1), 101021.

Jovanovic, M., Sjödin, D., & Parida, V. (2021). Co-evolution of platform architecture, platform services, and platform governance: Expanding the platform value of industrial digital platforms. Technovation, 102218.

Kamp, B., & Gibaja, J. J. (2021). Adoption of digital technologies and backshoring decisions: Is there a link? Operations Management Research, 1–23.

Kamp, B., & Wilson, J. (2021). Is industry 4.0 driving the backshoring of manufacturing activity?. Retrieved from https://iap.unido.org/articles/industry-40-driving-backshoring-manufacturing-activity

Kano, L., Tsang, E. W. K., & Yeung, H. W. (2020). Global value chains: A review of the multidisciplinary literature. Journal of International Business Studies, 51, 577–622.

Kearney, A. T. (2021). The 2021 Kearney global services location index. Toward a global network of digital hubs. Retrieved from https://www.kearney.com/digital/gsli

Kogut, B. (1985). Designing global strategies: Comparative and competitive value-added chains. Sloan Management Review (pre-1986), 26(4), 15.

Koh, L., Orzes, G., & Jia, F. J. (2019). The fourth industrial revolution (industry 4.0): Technologies disruption on operations and supply chain management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 9(6/7/8), 817–828.

Kraus, S., Palmer, C., Kailer, N., Kallinger, F. L., & Spitzer, J. (2019). Digital entrepreneurship: A research agenda on new business models for the twenty-first century. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(2), 353–375.

Lanzolla, G., Lorenz, A., Miron-Spektor, E., Schilling, M., Solinas, G., & Tucci, C. L. (2020). Digital transformation: What is new if anything? Emerging patterns and management research. Academy of Management Discoveries, 6(3), 341–350.

Laplume, A. O., Petersen, B., & Pearce, J. M. (2016). Global value chains from a 3D printing perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(5), 595–609.

McIvor, R., & Bals, L. (2021). A multi-theory framework for understanding the reshoring decision. International Business Review, 30, 101827.

McKinsey. (2019). Globalization in transition: The future of trade and value chains, June. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and-growth/globalization-in-transition-the-future-of-trade-and-value-chains

McKinsey. (2021). Rethinking operations in the next normal. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/rethinking-operations-in-the-next-normal#

McWilliam, S. E., Kim, J. K., Mudambi, R., & Nielsen, B. B. (2020). Global value chain governance: Intersections with international business. Journal of World Business, 55(4), 101067.

Miroudot, S. (2020). Reshaping the policy debate on the implications of COVID-19 for global supply chains. Journal of International Business Policy, 3(4), 430–442.

Monaghan, S., Tippmann, E., & Coviello, N. (2020). Born digitals: Thoughts on their internationalization and a research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(1), 11–22.

Müller, J., Dotzauer, V., & Voigt, K. (2017). Industry 4.0 and its impact on reshoring decisions of German manufacturing enterprises. Supply Management Research, 165–179.

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055.

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2021). On the costs of digital entrepreneurship: Role conflict, stress, and venture performance in digital platform-based ecosystems. Journal of Business Research, 125, 520–532.

Nambisan, S., Zahra, S. A., & Luo, Y. (2019). Global platforms and ecosystems: Implications for international business theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 50, 1464–1486.

Oliveira, L., Fleury, A., & Fleury, M. T. (2021). Digital power: Value chain upgrading in an age of digitization. International Business Review, 30, 101850.

Orzes, G., & Sarkis. (2019). Reshoring and environmental sustainability: An unexplored relationship? Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 141, 481–482.

Pananond, P., Gereffi, G., & Pedersen, T. (2020). An integrative typology of global strategy and global value chains: The management and organization of cross-border activities. Global Strategy Journal, 10, 421–443.

Pisani, N., & Ricart, J. E. (2016). Offshoring of services: A review of the literature and organizing framework. Management International Review, 56(3), 385–424.

Queiroz, M. M., Ivanov, D., Dolgui, A., & Wamba, S. F. (2020). Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: Mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Annals of Operations Research, 1–38.

Roozbeh Nia, A., Awasthi, A., & Bhuiyan, N. (2020). Chain and industry 4.0: A literature review. In U. Ramanathan & R. Ramanathan (Eds.), Sustainable supply chains: Strategies, issues, and models. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48876-5_1

Sahut, J. M., Iandoli, L., & Teulon, F. (2021). The age of digital entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 56, 1159–1169.

Scholten, K., Stevenson, M., & van Donk, D.-P. (2020). Guest editorial. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40, 1–10.

Sinkovics, N., Sinkovics, R. R., & Archie-Acheampong, J. (2021). Small- and medium-sized enterprises and sustainable development: In the shadows of large lead firms in global value chains. Journal of International Business Policy, 4, 80–101.

Steininger, D. M. (2019). Linking information systems and entrepreneurship: A review and agenda for IT associated and digital entrepreneurship research. Information Systems Journal, 29, 363–407.

Stentoft, J., & Rajkumar, C. (2020). The relevance of industry 4.0 and its relationship with moving manufacturing out, back and staying at home. International Journal of Production Research, 58(10), 2953–2973.

Strange, R. (2020). The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic and global value chains. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 47, 455–465.

Strange, R., & Zucchella, A. (2017). Industry 4.0, global value chains and international business. Multinational Business Review, 25(3), 174–184.

Sturgeon, T. J. (2021). Upgrading strategies for the digital economy. Global Strategy Journal, 11(1), 34–57.

The Economist. (2013). Outsourcing and offshoring. Here, there and everywhere. Special report. January 19th.

The Reshoring Institute. (2020). Reshoring & Sustainability. Beyond the Horizon, White Paper, February 26th.

UNCTAD. (2020). International production beyond the pandemic. World Investment Report.

van Hoeck, R. (2020a). Research opportunities for a more resilient post-COVID-19 supply chain–closing the gap between research findings and industry practice. International Journal of Operations & Production Management., 40(4), 341–355.

van Hoeck, R. (2020b). Responding to COVID-19 supply chain risks—Insights from supply chain change management, total cost of ownership and supplier segmentation theory. Logistics, 4(4), 23.

Verbeke, A. (2020). Will the COVID-19 pandemic really change the governance of global value chains? British Journal of Management, 31(3), 444.

von Briel, F., Recker, J., Selander, L., Jarvenpaa, S. L., Hukal, P., Yoo, Y., Lehmann, J., Chan, Y., Rothe, H., Alpar, P., Fürstenau, D., & Wurm, B. (2021). Researching digital entrepreneurship: Current issues and suggestions for future directions. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 48(1). https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.04833

Wieland, A., & Durach, C. F. (2021). Two perspectives on supply chain resilience. Journal of Business Logistics. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12271

Winkelhaus, S., & Grosse, E. H. (2020). Logistics 4.0: A systematic review towards a new logistics system. International Journal of Production Research, 58(1), 18–43.

World Trade Organization. (2021). World Trade as a Percentage of World GDP. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org

Yoo, Y., Boland, R. J., Jr., Lyytinen, K., & Majchrzak, A. (2012). Organizing for innovation in the digitized world. Organization Science, 23(5), 1398–1408.

Yoo, Y., Henfridsson, O., & Lyytenen, K. (2010). The new organizing logic of digital innovation: An agenda for information systems research. Information Systems Research, 21(4), 724–735.

Zaheer, H., Breyer, Y., & Dumay, J. (2019). Digital entrepreneurship: An interdisciplinary structured literature review and research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148, 119735.

Zhan, J. X. (2021). GVC transformation and a new investment landscape in the 2020s: Driving forces, directions, and a forward-looking research and policy agenda. Journal of International Business Policy, 4(2), 206–220.

Acknowledgement

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewer for their helpful suggestions. This work was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2019-106874GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). This work is developed with the support of Madrid Government (Comunidad de Madrid-Spain) with the project Excellence of University Professors(EPUC3M20) in the context of the V PRICIT (Regional Programme of Research and Technological Innovation). All authors have contributed equally to this paper. Authors appear in alphabetical order.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fernández, Z., Rodriguez, A. (2023). The Value Chain Configuration in the Digital Entrepreneurship Age: The Paradoxical Role of Digital Technologies. In: Adams, R., Grichnik, D., Pundziene, A., Volkmann, C. (eds) Artificiality and Sustainability in Entrepreneurship. FGF Studies in Small Business and Entrepreneurship. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11371-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11371-0_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-11370-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-11371-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)