Abstract

The dragonfly and damselfly (Odonata) fauna of the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea is impoverished, even compared to other Afrotropical archipelagoes, with a combined total of 22 species recorded with certainty on São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón. Trithemis nigra Longfield, 1936 from Príncipe is the only known endemic, although two reported but unidentified species may still prove to be endemic too. Most recorded species occur widely across and beyond Africa, and 27 equally widespread species are listed as potential additions. Several hypotheses for the fauna’s impoverishment are briefly discussed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Research History

The Odonata of the Gulf of Guinea have been poorly studied, even if the first records were provided a century ago (Martin 1908; Campion 1923). The first endemic taxon was described almost as long ago but remains the only one (Longfield 1936). Pinhey (1974) was the only specialist ever to visit, being on São Tomé for 2 weeks in April and May 1971. His review remains the main resource on all the islands’ faunas, only overlooking the material from Annobón treated by Compte Sart (1962). Just four species were added to the list for the three islands combined since Pinhey’s visit half a century ago, all very recently.

Species Diversity

Twenty-two species are known from the islands, of which 19 were recorded from São Tomé, 9 from Príncipe, and 7 from Annobón (Table 14.1). The specific identity of two species, however, is uncertain. These and two other species of interest are discussed below.

Gynacantha sp. — Pinhey (1974) saw a species of this genus or the similar Heliaeschna on São Tomé on four occasions, but these eluded capture. Two observers made sightings there since (see Table 14.1), suggesting the taxon is not rare. Both genera breed in shaded temporary pools. Adults are active at dusk, lurking in dense vegetation at daytime, making them challenging to find and catch. Pinhey (1974) remarked that “forest species of these genera on an isolated island might be expected to be distinctive.” While the Comoros, Seychelles and Mascarene archipelagos indeed have endemic Gynacantha species, these belong to the bispina-group that is absent on the western side of Africa (Dijkstra 2005). Twelve species occur on the continent nearest to São Tomé, any of which might be present on the Gulf of Guinea islands (Dijkstra 2016). Indeed, a female caught there by Gérard Filippi in March 2022 probably pertains to G. cylindrata Karsch, 1891. That species is widespread in western and central Africa. Females are hard to separate from those of G. vesiculata Karsch, 1891 (ranges are similar), so confirmation is desirable.

Orthetrum brachiale (Palisot de Beauvois, 1817) — This species and O. stemmale (Burmeister, 1839) were confused for 140 years (Pinhey 1979). Both occur widely on the tropical African mainland, while O. stemmale also extends to the nearby islands of Madagascar, the Mascarenes, and Seychelles in a variety of potential but unresolved taxa (see Table 14.2). While the latter’s presence in the Gulf of Guinea may thus seem likelier, both the material of Pinhey (1974, 1979) and Papazian et al. (2020) included O. brachiale only. Specimens in the Natural History Museum (London) and photographic records seen by the first author also agree with that species. Loureiro and Pontes (2013) reported O. stemmale from Príncipe without further comment, and Papazian et al. (2022) from São Tomé based on female specimens not assignable to other Orthetrum species found. Thus, while its presence seems very likely, confirmation with male specimens is required given the long history of taxonomic confusion.

Trithemis nigra Longfield, 1936 (Fig. 14.1) — Longfield (1936) described this as a subspecies of the Denim Dropwing T. donaldsoni (Calvert, 1899) based on two males, collected on Príncipe on 7 December 1932 and 1 January 1933. Pinhey (1970) raised the taxon to species level, which by morphology is nearest the Halfshade Dropwing T. aconita Lieftinck, 1969 and Congo Dropwing T. congolica Pinhey, 1970 (Damm et al. 2010). Alain Gauthier (pers. comm.) found T. nigra to be common in 1990. Indeed, it was found at 6 of 15 sites surveyed on the island’s eastern half in 2011 (Loureiro and Pontes 2013): all streams that were partly sunny and partly shaded by forest or shrubs. The species was not seen at fully shaded or seasonal streams, nor at standing or brackish water. While the limited distribution is below thresholds for Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, the survey identified no threats and therefore T. nigra is now listed as Near Threatened (IUCN 2021).

Zygonyx sp. — Species of this genus favour water with a strong current. Pinhey (1974) did not see “any Zygonyx near any of the waterfalls and swift-flowing streams” on São Tomé, although the well-dispersing Z. torridus (Kirby, 1889) was recently recorded (Papazian and Filippi 2019). Pinhey (1975) examined the unidentified female reported from Annobón by Longfield (1936), stating that “it appears to be flavicosta.” The species Z. flavicosta (Sjöstedt, 1900) is widespread in western and central Africa and cannot be confused with Z. torridus, although other continental species are similar. The Seychelles, Comoros and Madagascar all have endemic Zygonyx species; thus, the presence of an endemic species on such a distant island as Annobón cannot be ruled out.

A Poor Fauna?

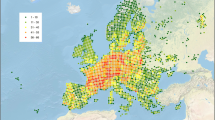

Considering how much suitable freshwater is present (Fig. 14.2), the 22 species known from all islands combined, and 19 from the largest and best-known island of São Tomé, seem exceptionally few. The Comoros, which geographically and ecologically are perhaps the most comparable island group, harbour 39 species in total, with 36 on the oldest and best-studied island of Mayotte. The Mascarenes and Seychelles (excluding Aldabra) are twice as far from the mainland, but have 29 and 19 confirmed species, respectively, while Mauritius and La Réunion each harbour 23 species (Dijkstra and Cohen 2021). Sixteen species have been reported from the Cape Verde islands, the only other major Afrotropical archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean (Martens et al. 2013). Although that is even fewer than in the Gulf of Guinea, those islands are also more isolated and substantially drier.

Comparing the species tallies of just a few archipelagos with very different sizes, histories, habitats, and degrees of isolation is problematic, however. Looking at the species themselves may therefore be more informative: 16 of the 22 recorded in the Gulf of Guinea are widespread across Africa, with most species’ ranges including the other archipelagos mentioned (and parts of Eurasia) as well. Twenty-seven additional species are found both on the adjacent continent and on these other islands, but have yet to be found on São Tomé, Príncipe, or Annobón (Table 14.2): probably at least ten of the more widespread ones are likely present in the Gulf of Guinea islands, pushing the total species diversity over 30.

Range-restricted species, too, are unexpectedly scarce. Pinhey (1974) noted that “compared to other orders, particularly Lepidoptera, rich in species or subspecies only known from these islands, the few endemics are remarkable for their paucity.” While a quarter of the Comoro, Mascarene, and Seychelles species are confined to their archipelagos (Dijkstra and Cohen 2021), Trithemis nigra from Príncipe is the only known endemic (Fig. 14.1). São Tomé is six times larger and twice as high but has no endemic Odonata. Socotra is larger but lies in a very dry corner of Africa (isolation is similar) and yet has similar numbers: 22 species including a single endemic (Van Damme et al. 2020). Furthermore, the mainland nearest Socotra has less than 50 species, whereas the Gulf of Guinea lies at the heart of the Afrotropics’ foremost centre of odonate diversity: well over 200 species are present in the hotspot centred on the Cameroon highlands (Clausnitzer et al. 2012).

While the islands have been poorly researched, their low species numbers can probably not be ascribed only to that. The wet climate with often rainy and cloudy weather may certainly impede the activity of adult odonates and indeed of odonatologists: Pinhey (1974) found that the hot humidity made it “almost unbearable in April to scramble up the mountain after about 9 a.m.” However, most widespread species are conspicuous provided it is warm enough. Sampling of five permanent forest streams in the south of São Tomé by the second author in September 2020, moreover, produced larvae of Ephemeroptera and Trichoptera, but no Odonata (Fig. 14.2) suggesting very low densities.

Perhaps the impoverishment on the islands in the Gulf of Guinea can be attributed to the same factors as the diversity on the continent around it. Odonate diversity and endemism is greatest at streams and other permanent waters, especially in areas with forest and varied relief such as in Lower Guinea (Clausnitzer et al. 2012). This is because species in stable habitats do not have to be good dispersers and can thus more easily become isolated and highly adapted to their specific environment. Species in seasonal habitats, by contrast, must be relatively tolerant and dispersive to survive (Dijkstra et al. 2014).

While very few of over 200 species found across from São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón may be capable of crossing over and colonising the islands, all of the less than 50 across from Socotra have to be. Orthetrum africanum (Selys, 1887), Rhyothemis notata (Fabricius, 1787), and Gynacantha cylindrata/vesiculata (see above) are the only species on São Tomé and Príncipe that are confined to Africa’s wetter and more forested west and centre, but favour rather open or temporary habitats and thus occur widely across equatorial Africa. Agriocnemis zerafica Le Roi, 1915 has a similar but more northerly range, being common at seasonal habitats across the Sahel but patchy in the rainforest to the south.

The islands’ only endemic fits the same pattern as those three species: the ancestors of the basitincta-group of species, to which T. nigra belongs, were inferred to prefer open standing water (Damm et al. 2010). The group first invaded flowing waters and then those with shade. The continental sister-species of T. nigra take an intermediate position in this transition, favouring more open and temporary sites in forests, such as flood pools near rivers. This capacity to penetrate the rainforest matrix and adapt to peripheral habitats likely allowed for the colonisation of Príncipe. This dispersal event was estimated to have occurred less than 3 million years ago (Damm et al. 2010).

Other factors may also have contributed to the poor odonate fauna in the Gulf of Guinea, such as habitat alteration by humans or volcanism, but these would seem unlikely to have impacted these insects specifically to the exclusion of other groups. The composition of the freshwater communities, however, may also be especially unsuited to Odonata. The second author noted unusually high densities of crustaceans and Sicydium gobies in his samples, likely caused by the absence of large fish predators. Although this is highly speculative, their abundance might in turn have led to rates of predation and/or competition that affect odonate larvae disproportionately.

Conclusions

We consider it unlikely (but not impossible) that prolonged fieldwork by a specialist may upend the current impression of a poor and unexceptional odonate fauna on São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón. Nonetheless, additional widespread Afrotropical species are expected, especially on Annobón, while the identities of the Gynacantha species on São Tomé and Zygonyx on Annobón remain to be clarified. Future work should focus on larvae, as sampling this life stage is less affected by wet weather, but also because their ecology might hold the key to the islands’ impoverished fauna.

References

Campion H (1923) Notes on dragonflies from the old-world islands of San Tomé, Rodriguez, Cocos-keeling and loo Choo. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 9(11):22–27

Clausnitzer V, Dijkstra K-DB, Koch R et al (2012) Focus on African freshwaters: hotspots of dragonfly diversity and conservation concern. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10:129–134

Compte Sart A (1962) Resultados de la expedición Peris-Alvarez a la isla de Annobón. 11. Odonata. Boletín de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural (B) 60:35–54

Damm S, Dijkstra K-DB, Hadrys H (2010) Red drifters and dark residents: the phylogeny and ecology of a Plio-Pleistocene dragonfly radiation reflects Africa’s changing environment (Odonata, Libellulidae, Trithemis). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 54:870–882

Dijkstra K-DB (2005) Taxonomy and identification of the continental African Gynacantha and Heliaeschna (Odonata: Aeshnidae). International Journal of Odonatology 8:1–33

Dijkstra K-DB (2016) African dragonflies and damselflies online. Available via http://addo.adu.org.za/. Accessed 21 Oct 2021

Dijkstra K-DB, Cohen C (2021) Dragonflies and damselflies of Madagascar and the Western Indian Ocean islands. Fondation Vahatra, Antananarivo

Dijkstra K-DB, Monaghan MT, Pauls SU (2014) Freshwater biodiversity and aquatic insect diversification. Annual Review of Entomology 59:143–163

IUCN (2021) The IUCN red list of threatened species: version 2020–2. Available via International Union for Conservation of Nature. https://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed 22 Oct 2021

Longfield C (1936) Studies on African Odonata, with synonymy, and descriptions of new species and subspecies. Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 85(20):467–498

Loureiro NS, Pontes L (2013) The Trithemis nigra (Odonata: Libellulidae) of Príncipe Island, gulf of Guinea. African Journal of Ecology 51:180–183

Martens A, de Santos LN, Hazevoet CJ (2013) Dragonflies (Insecta, Odonata) collected in the Cape Verde Islands, 1960-1989, including records of two taxa new to the archipelago. Zool Caboverd 4:1–7

Martin R (1908) Voyage de Leonarda Fea dans l’Afrique Occidentale, Odonates. Annali del Museo Civico di Storia Naturali Giacomo Doria, Genova 3(43):649–667

Papazian M, Filippi G (2019) Contribution à la connaissance des Odonates de l’archipel de São Tomé-et-Príncipe 1. Présence de Zygonyx torridus (Kirby, 1889) (Odonata Libellulidae). L’Entomologiste 75(5):265–267

Papazian M, Bonneau P, Filippi G, Nève G (2020) Contribution à la connaissance des Odonates de l’archipel de Sāo Tomé-et-Príncipe 2. Présence d’Agriocnemis zerafica Le Roi, 1915 (Odonata Coenagrionidae). L’Entomologiste 76(2):69–73

Papazian M, Filippi G, Coache A, Deffontaines J-B (2022) Contribution à la connaissance des Odonates de l'archipel de Sāo Tomé-et-Principe 3. Présence d’Ischnura senegalensis (Rambur, 1842), de Tramea limbata (Desjardins, 1835) et de Rhyothemis notata (Fabricius, 1787) (Odonata Coenagrionidae, Libellulidae). L’Entomologiste 78 (in press)

Pinhey E (1970) Monographic study of the genus Trithemis Brauer (Odonata: Libellulidae). Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Southern Africa 11:1–159

Pinhey E (1974) Odonata of the northwest Cameroons and particularly of the islands stretching southwards from the Guinea gulf. Bonner Zoologische Beiträge 25(1–3):179–212

Pinhey E (1975) A collection of Odonata from Angola. Arnoldia 7(23):1–16

Pinhey E (1979) The status of a few well-known African anisopterous dragonflies (Odonata). Arnoldia 8(36):1–7

Van Damme K, Vahalík P, Ketelaar R et al (2020) Dragonflies of Dragon’s blood island: atlas of the Odonata of the Socotra archipelago (Yemen). Rendiconti Lincei Scienze Fisiche e Naturali 31:571–605

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Dijkstra, KD.B., Tate, R.B., Papazian, M. (2022). Dragonflies and Damselflies (Odonata) of Príncipe, São Tomé, and Annobón. In: Ceríaco, L.M.P., de Lima, R.F., Melo, M., Bell, R.C. (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06153-0_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06153-0_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-06152-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-06153-0

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)