Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected children and their families. One of the many challenges families faced was limited or no access to age-appropriate reading material. On the one hand, sales data show that sales of children’s books, in particular activity books, increased markedly during lockdowns. On the other hand, spaces which grant children and families free access to books, such as daycare centers, schools, and public libraries, were closed for weeks at a time. This chapter sketches out the central role of books and reading in families as a pathway to literacy, education, and general well-being and draws on concepts such as book deserts and “book hunger” (Shaver 2020), before discussing the repercussions of limited book accessibility for families during the pandemic. Educational experts have hypothesized that children will experience a “COVID slide” in reading and that existing inequalities in reading progress will be exacerbated by prolonged shutdowns. The contribution also shows, however, how institutions and foundations, as well as individuals, have made books available to children and families in creative and pragmatic ways despite COVID-induced restrictions.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Parenting

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Family literacy

- Book accessibility

- Public libraries

- Inequality

- Children as readers

- Book ownership

- Book deserts

On December 31, 2020, as well-lit and curated tweets were posted documenting the books that tweeters had read in an unprecedented year, one encapsulated reading in 2020 for many bookish parents and carers. John Hay (@Hay47John) posted a picture of three messy piles of children’s books: board books and picture books, with bestselling titles such as Giraffes Can’t Dance piled up next to spin-offs of classics (The Very Hungry Caterpillar’s Easter Colors, The Very Hungry Caterpillar’s Christmas), interspersed with less recognizable titles, older editions of books by Dr. Seuss, and over a dozen Little Golden Books. “Here are all the books I read in 2020,” wrote John Hay (2020). The tweet struck a chord with me, as with many other Twitter users working from home and simultaneously caring for children during extended periods of lockdown. Just like in the viral tweet by scientist Gretchen Goldman, in which she juxtaposed a screenshot of her CNN interview with a “backstage” picture of a messy, toy-filled living room and a stuffed bookshelf containing, for instance, Wine for Dummies (Schwedel 2020), parents working from home may have routinely tripped over toys or books on their way from the Zoom room to the refrigerator and back. Just as Chandni Ananth et al.’s chapter in this volume (Chap. 12) discusses the concepts of “book accessibility” and “bookshelf insecurity” in relation to student lives during the pandemic, this chapter will center readers not otherwise represented in the volume: children, and by association, parents and other adults caring for children.

Children’s books do not exude “bookcase credibility” (@BCredibility).Footnote 1 They are hard to see on a Zoom screen, because they are more typically stored at children’s eye-level, in boxes near toys, or, for over-the-top bookish households, even in dedicated children’s book furnitureFootnote 2 instead of in more traditional shelving. However, while children’s books were not the “quarantine’s hottest accessory” (Hess 2020), they were, in many households with kids, the books most often handled and read in 2020. As daycare centers and schools closed in March 2020, parents struggled to reconcile their work responsibilities with their parenting responsibilities. For homeschooled children, digital devices (smartphones, tablets, laptops, or PCs) replaced the classroom, dramatically increasing children’s screen time and turning screen time into an obligation, not an option, for learning. Books and other media filled hours usually spent at extracurricular activities, socializing or in school and daycare. From celebrities who recorded read-alouds to fill children’s time (Maughan 2020) to free e-books published quickly to explain COVID to young children (Nosy Crow 2020)Footnote 3 and audiobook streaming services such as Scribd or Audible offering free audio books during the first wave of lockdowns (Machemer 2020)—bookish content seemed to be everywhere at once. Across markets, publishers and bookstores reported record sales for children’s books, especially activity books and coloring books. The UK Publishers Association (PA), as well as other similar organizations, celebrated these numbers as an indication of the importance of books. The PA wrote, not without pathos: “the nation turned to books for comfort, escapism and relaxation” and “reading triumphed, with adults and children alike reading more during lockdown than before” (Flood 2020).

This narrative, however recognizable it may be to readers of this book, is not representative. The sales increases, and the long hours spent reading to children in lockdown, picking classics from well-stocked middle- and upper-class bookshelves, is a highly selective one. It is a narrative that focuses on middle- and upper-class reading, book buying, and book ownership habits—as well as on the realities of white-collar workers relegated to home offices. As I have argued elsewhere (Norrick-Rühl 2016), and as Stevie Marsden argues in a recent article, book ownership and book display are two intertwined, and deeply classed, activities (2022). The classism and deep-seated inequalities inherent to book ownership do not start in adulthood: as the UK-based National Literacy Trust has shown, hundreds of thousands of children in the UK do not own a book of their own, while children who own books are six times more likely to read above the level expected for their age (2019).

Responding to and in conversation with these challenges, this chapter will try to give a voice to families and children who have suffered the brunt of the pandemic with schools and daycare centers closed, with extracurricular activities canceled, and with access to books severely limited for months at a time. Children in the background have, in the meantime, become a regular addition to video calls. Similarly, their pandemic experience should also be considered alongside the perspectives in this volume.

While John Hay’s tweet may have found appreciation on Twitter and resonated widely, it is naïve, even dangerous, to assume that the abundance of (children’s) books in academic households is the norm. As Lea Shaver writes in her landmark book Ending Book Hunger, we are “readers in a world of abundance” (2020). If you are reading this book—or, as she admits, hers, published by Yale University Press in 2020—you are part of a privileged minority of people who “struggle to manage our textual diets in the limited time we have” (ibid.). The same goes for this book and the problems and discussions probed in this entire volume. In a time of crisis, with a pandemic still sweeping the globe, the premise of this book may seem like a navel-gazing project of overprivileged academics. For instance, even as vaccinations became widely available, their distribution reinforced global inequalities in healthcare instead of alleviating them.

The full effects of pandemic school closures cannot yet be determined, but educational researchers were quick to hypothesize that the “COVID slide” in reading and mathematics would be much more problematic than the annual “summer slide” of achievement during the longer summer breaks (Kuhfeld and Tarasawa 2020). As Sarmishta Subramanian wrote in the Globe and Mail in May 2021, “This has been, for many kids, a year of loneliness and missed milestones, of diminished family gatherings and playtime, a year spent away from school and in the glare of a screen” (2021). In many places of the world, even outdoor playgrounds—public spaces for safe play, cognitive and physical development, and socializing—were closed.Footnote 4 For weeks at a time, media, including books, but more often screen-based media, replaced all types of social encounters beyond immediate family as well as physical activities and experiences.

Given my positionality as a university professor and mother of two children not yet in school, the impetus to write this chapter was certainly informed by my own observations and experiences. In keeping with Garance Maréchal’s understanding of autoethnography, I will attempt to combine “self-conscious introspection” and “analysis of personal resonance […] in dialogue with the representations of others” (2010). Countless scholars have turned to autoethnography to infuse their research during the pandemic, not only, but also due to closed libraries and shuttered campuses. As the editors of the recently founded Journal of Autoethnography mused when they founded a forum for autoethnographic research on and during the pandemic, “Researchers can use autoethnography to demonstrate how abstract, abrupt, and vast changes affect particular lives: specific and contextual experiences of stress and survival, grief and loss, loneliness and connection, desires for structure and normalcy” (Herrmann and Adams 2020). Reflexivity is necessary, however, to go beyond the personal anecdote and “name and interrogate the intersections between self and society, the particular and general, the personal and the political” (Adams et al. 2015, 2). Universities closed quickly and made it possible for parents to work from home while caring for their children. As difficult as it may have been, academics are white-collar workers and thus the risk of infection at the workplace was almost non-existent in the early stages of the pandemic (granted, hasty re-openings increased the risk of infection in higher education teaching).

Geographically, I am located in Germany, which offered a generous national safety net to lessen the challenges imposed by the pandemic. This locatedness (and my linguistic comfort zone) have also informed my sourcework, as almost all of my sources are either German-language sources or English-language sources. All of these details contribute to a privileged position from which I write. To give a fuller view, I will draw on a number of opinion pieces and early analyses about the effects of the pandemic on the children themselves, families more generally, and academic families specifically. Within the context of academic families, we are only starting to understand the catastrophic ripple effect of the so-called corona publication gap, which has already been seen to disproportionately affect women in academia (Viglione 2020).Footnote 5 While this is not the topic of this chapter, it is important to note that COVID has had a detrimental effect to women in the (academic) workplace more generally as well and that this is expected to have long-term consequences for gender equality.Footnote 6

The chapter will begin with observations on unequal book access and its effects. It will then consider the decrease in book accessibility during the pandemic, but also discuss the pragmatic and creative ideas and initiatives which brought books to families during lockdown(s).

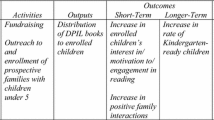

“Book deserts” Before the COVID-19 Pandemic

There is ample research to document the significance of access to print culture, in particular books, for children on their educational journey. In 2010, M. D. R. Evans, Jonathan Kelley, Joanna Sikora, and Donald J. Treiman made a splash with their paper on the availability of books in the homes of families across 27 nations—and the staggering success of book ownership as a predictor of academic achievement (2010). Their follow-up study collated data from 42 nations (Evans et al. 2014). In essence, their studies confirmed the positive correlation between exposure to books in the home and a “way of life that involves esteeming, reading and enjoying books” with academic achievement, regardless of the national contexts and specificities (Evans et al. 2014, 1573). This means that making books available to children in their homes is a high priority of literacy campaigns. There are several literacy projects that give books to parents of small children;Footnote 7 other programs, such as the long-standing and long-term initiative “Books for Ownership” led by Reading is FUNdamental in the USA, strive to reach children in schools, and close the gap in book availability.Footnote 8 These and other laudable initiatives try to put a book into the hand of every child. Research has shown that in the USA, the ratio of books per child is 13 to 1 for middle-class neighborhoods—whereas in low-income neighborhoods, the ratio is 1 age-appropriate book for every 300 children (Neuman and Dickinson 2006, 31). Compare these numbers to, for instance, the books pictured in John Hay’s tweet.

As indicated above, Lea Shaver has recently introduced the concept of “book hunger” to describe the unequal forms of access to books and other reading materials (2020). The metaphor of starvation does not sit well in a postcolonial parsing; the term “book desert,” used to denote areas where readers do not have access to books through libraries or bookstores, may be a more adequate term to employ (End Book Deserts n.d.). As Shaver argues, even in pre-pandemic conditions, more than half of the world’s population, and more than one billion children, did not have access to books and/or suffered from the impact of unequal access to books. Shaver emphasizes the significance of access to books and reading materials as means to be included not only in educational opportunities, but also democratic processes. Shaver, based in the USA, reminds her readers that millions of children living in the USA do not have access to sufficient funds for basic needs, let alone books (2020).

Importantly, however, books in the home can only fulfill their potential if the adult caregivers model a culture of reading and make time to explore the books together. In fact, German author and literacy campaigner Kirsten Boie heavily criticized an initiative in 2019 which offered one million books to children—but only if they came to a bookshop to pick the book up. Boie asked, “Do one million free books really mean one million families will start reading to their children all of a sudden?” and called for more nuanced and thoughtful deployment of resources in a widely read op-ed (2019).

Exacerbating this, there are also countless children whose access to books is limited not through lack of resources, but because they are growing up in so-called low-literate families or low literacy homes in which the adults do not read well and lack the skills and knowhow to share a culture of reading with their children. Interestingly for our context here, in German, these families are denoted as “buchferne Familien” (families at remove from books), which emphasizes the book as a physical object in the home more than the English term. Germany’s Stiftung Lesen has conducted longitudinal studies which show that the percentage of families in Germany which do not read aloud has not changed since 2013, despite all the funding and activities meant to boost family literacy (2019). For these children in particular, access to books and experiences with a culture of reading are limited to public daycare centers and schools and their integration of library visits and reading activities. A recent study in Germany showed that 91% of daycare centers integrate books into their daily routine (Stiftung Lesen 2021). This is good news in the first instance, but also emphasizes how shutdown deprived children of these impulses.

For book-centered academics in disciplines such as book history and publishing studies, whose research circles around books as objects and commodities, their materiality, history, and significance, Shaver’s statistics give pause. It is difficult to acknowledge that even within wealthy, western (and westernized) countries, where there is a massive overproduction of books, countless children still live in households without books or even without access to libraries. It is, however, imperative that book studies scholars and book historians refocus their gaze and realign expectations.

The unequal distribution of books and other print materials has found attention, for instance, in Susan B. Neuman and Donna Celano’s work comparing access to print across different types of neighborhoods within the confines of one US industrial city (2001). Considering the implications is one side of the coin, the other is improving the situation and “leveling the playing field.” Besides the aforementioned initiatives to give books to families, a functioning public library infrastructure is key, though Neuman and Celano have also documented the challenges associated with “leveling the playing field,” using a case study of Philadelphia Library’s branch system in the early 2000s. As Neuman and Celano show, alleviation of inequalities in access and literacy outcomes is multifaceted and complex (2006). Challenges notwithstanding, research has clearly proven the value of libraries within communities and specifically for children and families. In fact, a 2013 Pew Research Center study showed that the value of libraries becomes particularly apparent to adults when those adults become parents or caregivers: “parents of children under 18 are more likely than other adults to say the library is very important […] and, among parents, mothers are more likely than fathers to say libraries are either very or somewhat important (87% vs. 80%)” (Zickuhr et al. 2013a). In addition, and significantly, “[l]ower income parents are more likely to view library services as very important” (Zickuhr et al. 2013b). In the press release for the study, a researcher explained,

From the minute we started talking to library patrons in this research, it was apparent that parents are a special cohort because of their affection for libraries, their deep sense that libraries matter to their children, and their own use of libraries […] They do more and they are eager for more library services of every kind—ranging from traditional stuff like books in stacks and comfortable reading spaces to high-tech kiosks and more e-books and mobile apps that would allow them to access library materials while they are on the go. (Rainie 2013)

Pragmatic solutions, accessibility, and family-friendly opening hours are key in making books and other media and services available to families. While there is certainly much room for improvement in the public library system, public libraries all over the worldFootnote 9 manage to achieve impressive successes as community centers and literacy hubs despite constant funding pressures. These funding pressures can be seen most clearly in the UK, where over 800 library branches have closed in the last decade alone (Flood 2019). Most probably, the staggering economic cost of COVID will also trickle down to public institutions like libraries, schools, and universities, which may further exacerbate the issue of library funding and, by extension, book accessibility. These effects are not yet measurable. We can, however, look back to the past 18 months to get an impression of the shift in book accessibility during the pandemic, when book accessibility for children and families dropped dramatically.

Book Accessibility for Children and Families During the Pandemic

Mostly without notice, libraries, schools, and daycare centers closed. From one day to the next, school-aged children were forced to rely on the devices in their home to access their school and learning materials. While toilet paper and yeast were the products most widely spoken about in relation to a lack of stock, parents and other caregivers were also frantically looking for school supplies, craft supplies, as well as books and other media products to keep their children occupied for long lockdown days. Even for families able and willing to buy new books, the logistics of acquiring new reading materials were not always straightforward or available to people living outside of urban centers. Supermarkets generally offered a small book and magazine section through rack jobbers, but these sites for book acquisition were hotly debated during the pandemic and partly cordoned off in Germany to avoid unfair competition with shuttered bookstores. Independent bookstores creatively transitioned to curbside pick-up and delivery options,Footnote 10 while Amazon even de-prioritized book distribution in the early days of lockdown in the USA (Milliot and Maher 2020).

Logistics notwithstanding, book sales, especially sales of children’s books, were surprisingly stable. Libraries, however, struggled with regulations and requirements and were not able to offer their full services. E-lending services boomed, such as the Onleihe in Germany. A total of 23.6% more books were borrowed via Onleihe in 2020 than in 2019 (ekz 2021). In North America, e-book lending on OverDrive, which works with 90% of libraries 283 to offer e-books to their patrons, increased by 53% on 284 average between mid-March and June 2020. Books for young readers who are already secure readers were particularly popular. As OverDrive said, YA nonfiction e-book checkouts were up 122% and juvenile fiction was up 93%. OverDrive also saw more than double the number of new digital library cards than in the same period in 2019 (Pressman 2020). However, e-lending does not work for books for early readers, who need board books and picture books or books from early readers series which adhere to specific text-illustration ratios and have typography which is prepared precisely for unexperienced readers. As Maryanne Wolf has emphasized, printed materials are better for learning to read, and screens then can be employed for learning digital literacy, in pursuit of what she calls the “biliterate reading brain” (2018, 12).

Later in 2020, UK bookstores and industry associations launched a “books are essential” campaign to keep bookstores open during the second wave of lockdowns. Claire Squires voiced her discomfort with the “books are essential” slogan, pointing out that books may be essential, but bookstores are not the only place to get books.

The argument for bookshops as essential, however, despite all the claims for civilisation and hope, is as much economic as cultural: the book as commodity as well as beacon […]. The elision of books with bookshops is evident in this argument. Books are available in bookshops, books are good, ergo bookshops are good. And indeed bookshops—large and small—can provide comforting and welcoming social spaces to some; with their latter-day inclusion of espresso machines, events programmes and play spaces for children. But of course, so do libraries, which have a much greater role in social inclusion, not least in terms of digital accessibility and warm dry spaces for the homeless. (Squires 2020)

Lockdowns deprived communities of these safe spaces. As the Seattle-based library manager Darcy Brixey said, “Libraries are one of the few places that anybody can go to without the expectation of having to buy something. […] That’s called loitering in every other business except a public library” (quoted in Ashworth 2020). Brixey emphasized that many public libraries have transitioned to being not only libraries for reading materials, but also for objects of daily use, such as tools, baking accessories, and even clothing for job interviews. As Brixey said, “Libraries […] serve as a lifeline for low-income families” (ibid.). Libraries also offer free Wi-Fi and free computer use to their patrons, which is of particular importance to the most economically deprived and the homeless.

As Sarmishta Subramanian and many others have observed, “The pandemic exacerbates pre-existing problems” (2021). While some families certainly increased spending on children’s books, with an uptick particularly palpable in the area of activity books and educational materials, and some parents were able to dedicate more time than usual to reading together with their children, this is only a small part of the bigger picture. For many families, access to children’s books was severely diminished, as daycare centers and libraries closed and school literacy programs fell victim to COVID restrictions.

The shutdowns, as necessary as they were, deprived children and families of books. Most prominently, library infrastructure was no longer available, whether it was public libraries or libraries associated with schools, churches, or books made available informally through and in other community spaces. In a poignant piece in The Washington Post, Maggie Smith described this shift:

Since March, there have been many places I miss. I miss places in general—destinations, spots on a map that are not my home, cities and countries I could drive to or fly to. Don’t even get me started on how, despite my lifelong fear of heights, I miss airplanes. I miss being above the clouds and seeing the quiltlike landscape beneath me transform over the hours.

But although I miss faraway destinations, what I miss most on a daily basis are my places—the coffee shops I loved to write in, the restaurants and bars where I’d unwind with my friends. One of the places my kids and I miss most is the public library. (2020)

During the pandemic, Lea Shaver herself went on record to speak about the effects of the pandemic on her household and on book access more widely. She stressed the difficulties of providing her children with new books to read on a regular basis, but also emphasized the lack of adequate reading materials for emerging readers to spend time with on their own. Shaver explained that the “children’s book market tilts heavily toward gift books, especially more complex picture books that adults will enjoy reading to kids, or chapter books that an older child can read on their own. Materials that a young child can read with just a little help are in much shorter supply” (StoryWeaver 2020).

Even for families with books at home, then, accessibility to new or adequate books and reading materials, as well as other educational and recreational media available at the library, was highly limited. Juggling work, anxieties surrounding the pandemic, and other responsibilities, many parents turned on screens, as a replacement for nearly everything the children had usually spent time doing. A concrete example is the astounding success of children’s home fitness and wellness videos on YouTube and/or offered as apps, with Jaime Amor’s beloved Cosmic Kids Yoga channel just one of many examples of businesses which profited from the pandemic surge in screen time (Amor 2021).Footnote 11

In lieu of the classroom, the halls, and the recess spaces of educational institutions, children relied on devices and screens to stay in touch with their teachers and fellow students as well as friends and relatives. Children were also, by necessity, “parked” in front of screens while their parents worked from home in front of other screens. As two journalists writing for the New York Times wrote in April 2020, “Just weeks ago, the sight of our toddlers entranced by screens first thing in the morning would have caused panic. Now? It’s a typical Tuesday. In fact, screens are on as we write this article. How else could we do it?” (Cheng and Wilkinson 2020). I would be remiss in my autoethnographic reflection if I didn’t admit that screen time increased significantly in our household as well, to a degree we never would have foreseen or accepted prior to the pandemic. In response to parental anxieties, the American Association of Pediatrics (AAP) quickly released a statement in March 2020 to clarify that the usual limits of screen time—described as “no screen time for children under 18 months and less than one hour of daily high-quality programming for 2- to 5-year-olds” (ibid.)—were probably too idealistic in light of the COVID lockdowns (AAP 2020). While the AAP and the New York Times both sought to alleviate parental fears of fallout from too much screen time in the early days of lockdown, the prolonged lockdowns have proven to have very real consequences in relation to the mental, physical, and educational development of children. One example is the so-called “pandemic slide” in reading.

It is already clear across national contexts that the “pandemic slide” in reading proficiency will cause long-term learning deficits. Research conducted by the German literacy organization Stiftung Lesen in 2020 showed that while readers, including children, who read regularly spent more time reading in 2020 than usual, the percentage of people, including children, who do not read regularly did not change substantially (Emmerlich 2021). In a similar vein, the UK National Literacy Trust showed that while children’s average reading times increased in the pandemic, the reading gender gap widened just as some children indicated their cramped living situations did not allow them a quiet place to read when everyone was at home (Clark and Picton 2020).

Creative Solutions, Pragmatic Approaches

As I have stressed, the mid-term and longer-term consequences of the pandemic are not measurable yet, but in order to end on a more optimistic note, I would like to gesture at creative solutions and pragmatic, hands-on approaches to increase book accessibility for underserved readers. These approaches and ideas were not all new; Leah Price describes some of the work of “biblioactivists” or “biblioboosters” in What We Talk About When We Talk About Books (Price 2019, 153–162). However, for instance, so-called little free librariesFootnote 12 had their 15 minutes of fame during the pandemic, offering new reading materials to readers at no cost, and under ideal outdoor social distancing conditions. One new little free library steward reported that puzzles were even more popular than books, circulating through in an astounding speed (Larusso 2020).

Simultaneously, as soon as they were able, many actual libraries adapted to the new situation and lent out pre-packaged book boxes to families. Some libraries even became hybrid healthcare centers, hosting vaccine clinics and offering free food in outdoor refrigerators to library patrons in need (Sausser 2021). Importantly, many libraries kept their Wi-Fi on, despite closures, to give patrons continuous access. Statistics such as those from the Washington DC Public Library emphasize how central these services were: by June 2020, they had registered almost 20,000 different devices logging in for more than 60,000 sessions on the internet (Wilburn 2020).

Underserved readers in particular were targeted through book distribution in shelters, food banks, and through other relief agencies: picking two of many examples, the nonprofit Win made books available in Brooklyn shelters, while on the other end of the USA, books were distributed to Alaskan children through the Alaska Fishing Industry Relief Mission and First Book (Aridi 2020; Locke 2020). Dolly Parton, whose Imagination Library is an unprecedented example for private philanthropism in the literacy sector, continued to distribute books and launched a read-aloud series for children online—in addition to funding and campaigning for vaccination (Snapes 2020).

Despite creative solutions and pragmatic approaches such as these, the pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities in the education system and has reinforced structural issues such as unequal access to books. While this chapter focused mainly on German, UK, and US perspectives, the global incongruencies in dealing with the pandemic are reflective of the inequalities that the world’s children are growing up with and into. A stark measure of the global differences is the number of school days missed by children in different countries, as compiled and published by UNICEF in the spring of 2021. In Panama, for instance, schools were fully closed for 211 days from March 2020 to February 2021 (UNICEF 2021). The UNICEF study also emphasized that the countries where schools remained fully closed the longest were often the countries in which children did not have regular access to the internet. Thus, the worldwide educational and digital divide increased further.

Book studies and book history tends to privilege the culture of bookishness, considering book collecting and bibliophilia from shelfies to artists’ books, and foregrounding the publishing industry and its often beautiful and culturally significant products, from cover to blurb. As this chapter has tried to show, it is crucial that we also engage more seriously and mindfully with questions of literacy, book accessibility, and inequality. Elmer the Elephant, The Very Hungry Caterpillar and all those other beloved children’s book characters and protagonists may have been invisible in the Zoom room, but the work lies ahead of us as researchers: not only, but particularly in the wake of this pandemic. As researchers, we have the tools and methods to study and consider issues such as unequal access to books and book accessibility issues during and continuing after the pandemic. We also, in our publications and networks, have the platforms to knowledgably shed light on these issues and, ideally, to help alleviate unequal access to books—by advocating for libraries, supporting literacy programs, and spreading the word about the immeasurable impact of book accessibility and book ownership on children’s educational outcomes.

Notes

- 1.

Bookcase Credibility Twitter account. https://twitter.com/BCredibility.

- 2.

See, for instance, this rolling children’s book shelf by Vertbaudet, a French children’s clothing and accessories brand: https://www.vertbaudet.de/kinder-bucherregal-mit-rollen-picknick-wei.htm?ProductId=705010424&FiltreCouleur=6350#vb-fp-tab%2D%2D2. Accessed October 29, 2021.

- 3.

- 4.

For context, cf. for instance this opinion piece on playground closures in Australia: Goldfeld (2021).

- 5.

See also recent work such as Ribarovska (2021). In the interest of full disclosure, I would like to stress that any part I had in the conference “Bookshelves in the Age of the COVID-19 Pandemic” as well as this chapter and my other contributions to this volume were only made possible by an atypically robust support infrastructure, including the efforts of my local daycare center to re-open as safely as possible for children of working parents. My deepest thanks are due to my children’s wonderful daycare teachers at KiTa Bunte Wiese. I appreciate them, and the work they do, more than I will ever be able to express.

- 6.

Cf. for instance Lerchenmüller (2021).

- 7.

- 8.

Reading is FUNdamental [RIF] (n.d.).

- 9.

For a wonderful visualization of public library distribution and funding worldwide, see the IFLA Library Map of the World. https://librarymap.ifla.org/.

- 10.

- 11.

Discussed in Phelan (2020).

- 12.

Neighborhood book exchanges, usually made available in publicly accessible shelving outdoors.

References

@BCredibility. Twitter. https://twitter.com/BCredibility. Accessed October 29, 2021.

AAP. 2020. Finding Ways to Keep Children Occupied During These Challenging Times. [Press release], March 17. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2020/aap-finding-ways-to-keep-children-occupied-during-these-challenging-times/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Adams, Tony E., Holman, Stacy Linn and Ellis, Carolyn. 2015. Autoethnography. Oxford: Oxford UP.

American Library Association. n.d. Books for Babies. https://www.ala.org/united/products_services/booksforbabies. All websites accessed October 29, 2021.

Amor, Jaime. 2021. Cosmic Kids Yoga. https://cosmickids.com/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Anderson, Porter. 2021. The UK’s BookTrust Revitalizes Its “BookStart Baby Bag” Program. Publishers Weekly, August 25. https://publishingperspectives.com/2021/08/the-uks-booktrust-revitalizes-its-bookstart-baby-bag-program/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Aridi, Sara. 2020. With Schools Closed, Bringing Books to Students in Need. The New York Times, April 23. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/neediest-cases/first-book-school-closed-coronavirus.html. Accessed October 29, 2021

Ashworth, Boone. 2020. Covid-19’s Impact on Libraries Goes Beyond Books. Wired, March 25. https://www.wired.com/story/covid-19-libraries-impact-goes-beyond-books/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Boie, Kirsten. 2019. Eine Million verschenkte Chancen. Die ZEIT 32, August 1. https://www.zeit.de/2019/32/weltkindertag-buecher-stiftung-lesung-bildung-sprachentwicklung. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Beltz & Gelberg. 2020. Coronavirus. Ein Buch für Kinder über Covid-19 [press information]. https://www.beltz.de/kinder_jugendbuch/produkte/produkt_produktdetails/44094-coronavirus.html. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Cheng, Erika R. and Tracey A. Wilkinson. 2020. Agonizing Over Screen Time? Follow the Three C’s. The New York Times, April 13. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/parenting/manage-screen-time-coronavirus.html. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Chu, Deborah. 2020. Independent Bookstores Delivering during the Lockdown in Glasgow and Edinburgh. The List, April 23. https://www.list.co.uk/article/115882-independent-bookstores-delivering-during-the-lockdown-in-glasgow-and-edinburgh/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Clark, Christina and Irene Picton. 2020. Children and young people’s reading in 2020 before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. National Literacy Trust. https://cdn.literacytrust.org.uk/media/documents/National_Literacy_Trust_-_Reading_practices_under_lockdown_report_-_FINAL.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2021.

ekz. 2021. Run auf digitales Lesen: Onleihe boomt im Lockdown 2020 und treibt Digitalisierung voran. https://www.ekz.de/news/run-auf-digitales-lesen-onleihe-boomt-im-lockdown-2020-und-treibt-digitalisierung-voran-439. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Emmerlich, Simon. 2021. Stiftung Lesen: Jugendliche lesen in der Pandemie mehr. BR.de, March 2. https://www.br.de/nachrichten/kultur/stiftung-lesen-jugendliche-lesen-in-der-pandemie-mehr,SQUWvSP. Accessed October 29, 2021.

End Book Deserts. n.d. https://www.endbookdeserts.com/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Evans, Mariah D.R. et al. 2010. Family scholarly culture and educational success: Books and schooling in 27 nations. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 28 (2):171–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2010.01.002.

———. 2014. Scholarly Culture and Academic Performance in 42 Nations. Social Forces 92 (4):1573–1605. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43287580.

Flood, Alison. 2019. Britain has closed almost 800 libraries since 2010, figures show. The Guardian, December 6. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/dec/06/britain-has-closed-almost-800-libraries-since-2010-figures-show. Accessed October 29, 2021.

———. 2020. UK book sales soared in 2020 despite pandemic. The Guardian, April 27. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/apr/27/uk-book-sales-soared-in-2020-despite-pandemic. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Goldfeld, Sharon. 2021. Children need playgrounds now, more than ever. We can reduce COVID risk and keep them open. The Conversation, August 23. https://theconversation.com/children-need-playgrounds-now-more-than-ever-we-can-reduce-covid-risk-and-keep-them-open-166562. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Gross, Jenny. 2020. Curbside Pickup. Bicycle Deliveries. Virtual Book Discussions. Amid Virus, Bookstores Get Creative. The New York Times, March 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/17/us/independent-bookstores-coronavirus.html. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Hay, John (@Hay47John). 2020. Twitter post. December 31. https://twitter.com/Hay47John/status/1344673780849733632. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Herrmann, Andrew, and Troy Adams. 2020. Living Through/With COVID-19: Using Autoethnography to Research the Pandemic. UC Press Blog, September 1. https://www.ucpress.edu/blog/51794/living-through-with-covid-19-using-autoethnography-to-research-the-pandemic/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Hess, Amanda. 2020. The “Credibility Bookcase” Is the Quarantine’s Hottest Accessory. The New York Times, May 1. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/01/arts/quarantine-bookcase-coronavirus.html. Accessed 9 October 2021.

IFLA Library Map of the World. https://librarymap.ifla.org/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Kamin, Debra. 2020. These new books are here to teach your kids about social distancing, masks and covid-19. The Washington Post, September 1. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2020/09/01/these-new-books-are-here-teach-your-kids-about-social-distancing-masks-covid-19/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Kuhfeld, Megan and Beth Tarasawa. The COVID-19 slide: What summer learning loss can tell us about the potential impact of school closures on student academic achievement. NWEA Brief, April 2020. https://www.nwea.org/content/uploads/2020/05/Collaborative-Brief_Covid19-Slide-APR20.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Larusso, Jessica. 2020. How I Built A Little Free Library During the Pandemic. 5280, September 29. https://www.5280.com/2020/09/how-i-built-a-little-free-library-during-the-pandemic/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Laud, Anja. 2020. Corona-Virus in Frankfurt: Mit Lieferservice aus der Krise. Frankfurter Rundschau, March 22. https://www.fr.de/thema/corona-virus-sti1424368/corona-virus-frankfurt-lieferservice-krise-13609610.html.

Lerchenmüller, Carolin, Leo Schmallenbach, and Marc J. Lerchenmüller. 2021. “Gender Publication Gap” 2020 größer geworden. Forschung & Lehre, October 10. https://www.forschung-und-lehre.de/forschung/gender-publication-gap-2020-groesser-geworden-4086/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Locke, Charley. 2020. Special Delivery: Thousands of Books. The New York Times, December 26. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/neediest-cases/first-book-school-closed-coronavirus.html. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Machemer, Theresa. 2020. Listen to Hundreds of Free Audiobooks, From Classics to Education Texts. Smithsonian Mag, April 6. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/audible-now-offers-hundreds-audiobooks-free-180974606/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Maréchal, Garance. 2010. Autoethnography. In Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos & Elden Wiebe (eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research, vol. 1, pp. 44–46. Thousand Oaks, SAGE, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412957397.n19.

Marsden, Stevie. 2022. “I take it you’ve read every book on the shelves?” Demonstrating taste, value and class through owning and displaying books. English Studies 103 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/0013838X.2022.2087033

Maughan, Shannon. 2020. Coronavirus Response: Celebrities Reading Kids’ Books. Publishers Weekly, October 6. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-industry-news/article/84535-coronavirus-response-celebrities-reading-kids-books.html. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Milliot, Jim and John Maher. 2020. Amazon Deprioritizes Book Sales Amid Coronavirus Crisis. Publishers Weekly, March 17. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/bookselling/article/82713-amazon-deprioritizes-book-sales-amid-coronavirus-crisis.html. Accessed October 29, 2021.

National Literacy Trust. 2019. Gift of reading: children’s book ownership in 2019. Press release, November 29. https://literacytrust.org.uk/research-services/research-reports/gift-reading-childrens-book-ownership-2019/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Neuman, Susan B., and Donna Celano. 2001. Access to print in low-income and middle-income communities: An ecological study of four neighborhoods. Reading Research Quarterly 36 (1): 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1598/rrq.36.1.1.

———. 2006. The knowledge gap: Implications of leveling the playing field for low-income and middle-income children. Reading Research Quarterly 41 (2), 176–201. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.41.2.2.

Neuman, Susan B. and David K. Dickinson, eds. 2006. Handbook of Early Literacy Research. Volume 2. New York, NY: Guilford.

Norrick-Rühl, Corinna. 2016. (Furniture) Books and Book Furniture as Markers of Authority, TXT (1), 3–8.

Nosy Crow. 2020. Out now: a free information book explaining the coronavirus to children, illustrated by Gruffalo illustrator Axel Scheffler. April 6. https://nosycrow.com/blog/released-today-free-information-book-explaining-coronavirus-children-illustrated-gruffalo-illustrator-axel-scheffler/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Rainie, Lee. 2013. Quoted in Pew Research Center. 2013. Parents, Children, Libraries and Reading [press release]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/05/01/parents-children-libraries-and-reading/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Phelan, David. 2020. Cosmic Kids: How a Kids’ Yoga App Became a World-Beater. Forbes, June 17. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidphelan/2020/06/17/cosmic-kids-how-a-kids-yoga-app-became-a-world-beater/?sh=57265e2169cd. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Pressman, Aaron. 2020. E-book reading is booming during the coronavirus pandemic. Fortune, June 18. https://fortune.com/2020/06/18/ebooks-what-to-read-next-coronavirus-books-covid-19/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Price, Leah. 2019. What We Talk About When We Talk About Books. New York: Basic Books.

Reading is FUNdamental [RIF]. n.d. Books for Ownership. https://www.rif.org/literacy-network/our-solutions/books-ownership. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Ribarovska, Alana K. et al. 2021. Gender inequality in publishing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun (91): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.11.022.

Sausser, Lauren. 2021. Libraries Have Become Hybrid Health Care Hubs Amid Pandemic. USNews, March 15. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/south-carolina/articles/2021-03-15/libraries-have-become-hybrid-health-care-hubs-amid-pandemic. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Schwedel, Heather. 2020. An Interview with the Scientist and Mom Who Had a Little Secret During Her CNN Appearance. Slate, September 17. https://slate.com/human-interest/2020/09/cnn-mom-pants-interview.html. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Shaver, Lea. 2020. Ending Book Hunger. Access to Print Across Barriers of Class and Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale UP. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300249316.

Smith, Maggie. 2020. Covid-19 took away our family’s second home: The library. The Washington Post, October 19. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2020/10/20/public-library-closed-covid-19/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Snapes, Laura. 2020. Dolly Parton partly funded Moderna vaccine research. The Guardian, November 17. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/nov/17/dolly-parton-partly-funded-moderna-covid-vaccine-research. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Squires, Claire. 2020. Essential? Different? Exceptional? The Book Trade and COVID-19. C21. Literature. Journal of 21st-Century Writings, December 10. https://c21.openlibhums.org/news/403/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Stiftung Lesen. n.d. Lesestart. https://www.lesestart.de/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

———. 2019. Vorlesen: Mehr als Vor-Lesen! Vorlesestudie 2019. https://www.stiftunglesen.de/fileadmin/PDFs/Vorlesestudie/Vorlesestudie_2019_01.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2021.

———. 2021. Kitas als Schlüsselakteure in der Leseförderung. Vorlesestudie 2021. https://www.stiftunglesen.de/fileadmin/Bilder/Forschung/Vorlesestudie/20211021_VLS_final.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2021.

StoryWeaver. 2020. StoryWeaver Community Spotlight: Professor Lea Shaver on using StoryWeaver’s Re-level Feature to create homeschooling materials. https://storyweaver.org.in/v0/blog_posts/452. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Subramanian, Sarmishta. 2021. What is one thing we can do about children’s learning loss during the pandemic? Put a book in their hands. The Globe and Mail, May 1. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/books/article-what-is-one-thing-we-can-do-about-childrens-learning-loss-during-the/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

UNICEF. 2021. One Year of COVID-19 and School Closures. Geneva: UNICEF. https://data.unicef.org/resources/one-year-of-covid-19-and-school-closures/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Viglione, Giuliana. 2020. Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here’s what the data say. Nature.com, May 20. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01294-9. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Wilburn, Thomas. 2020. Libraries Are Dealing With New Demand For Books And Services During The Pandemic. NPR.org, June 16. https://www.npr.org/2020/06/16/877651001/libraries-are-dealing-with-new-demand-for-books-and-services-during-the-pandemic. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Wolf, Maryanne. 2018. Reader, Come Home. The Reading Brain in a Digital World. New York: Harper.

Zickuhr, Kathryn, Lee Rainie and Kristen Purcell. 2013a. Parents, Children, Libraries, and Reading. Part 4: Parents and Libraries. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/05/01/part-4-parents-and-libraries/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

———. 2013b. Parents, Children, Libraries, and Reading. Summary of Findings. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/05/01/parents-children-libraries-and-reading-3/. Accessed October 29, 2021.

Acknowledgments

I owe a debt of gratitude to my colleagues Dr. Caroline Koegler and Ellen Barth (University of Muenster) for insightful comments on an earlier version of this article. My thanks go to Annika Klempel, Tobias Mestermann and Alexander Vos for research and editorial assistance. Thanks are also due to John Hay for permission to quote his tweet.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Norrick-Rühl, C. (2022). Elmer the Elephant in the Zoom Room? Reflections on Parenting, Book Accessibility, and Screen Time in a Pandemic. In: Norrick-Rühl, C., Towheed, S. (eds) Bookshelves in the Age of the COVID-19 Pandemic . New Directions in Book History. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05292-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05292-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-05291-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-05292-7

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)